The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Recruiting for World War I

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Recruiting for World War I

World War I broke out in 1914 but for some years before that the rapid rise of Germany, the increasing instability in Europe, and the likelihood that Australia would be expected to send assistance if Great Britain became involved in war had caused the Australian government to introduce compulsory military training and take other steps to ensure national preparedness. The Defence Act provided that all men aged 18 to 60 were liable to be called upon to serve in time of war, but only within Australia, and in 1911 a system of universal national service began whereby all boys aged between 12 and 18 were trained as cadets and then had to serve part-time in the Citizens' Military Forces (CMF) until age 25.

Cadets at school trained there after hours, supervised by teachers. Those under 19 who had left school trained one night a week or on Saturday afternoons at local schools, drill halls or sporting fields. Trainees aged 19 to 25 were in the CMF and trained on Saturday afternoons. They were paid an allowance and were known as 'Saturday afternoon soldiers'. [1] Registration for training was compulsory, although those living more than five miles (8 kilometres) from a designated training place were exempted, along with those medically unfit. Many eligible males did not in fact register, particularly boys in rural areas for whom farm work was a higher priority.

'Come on boys, follow the flag'

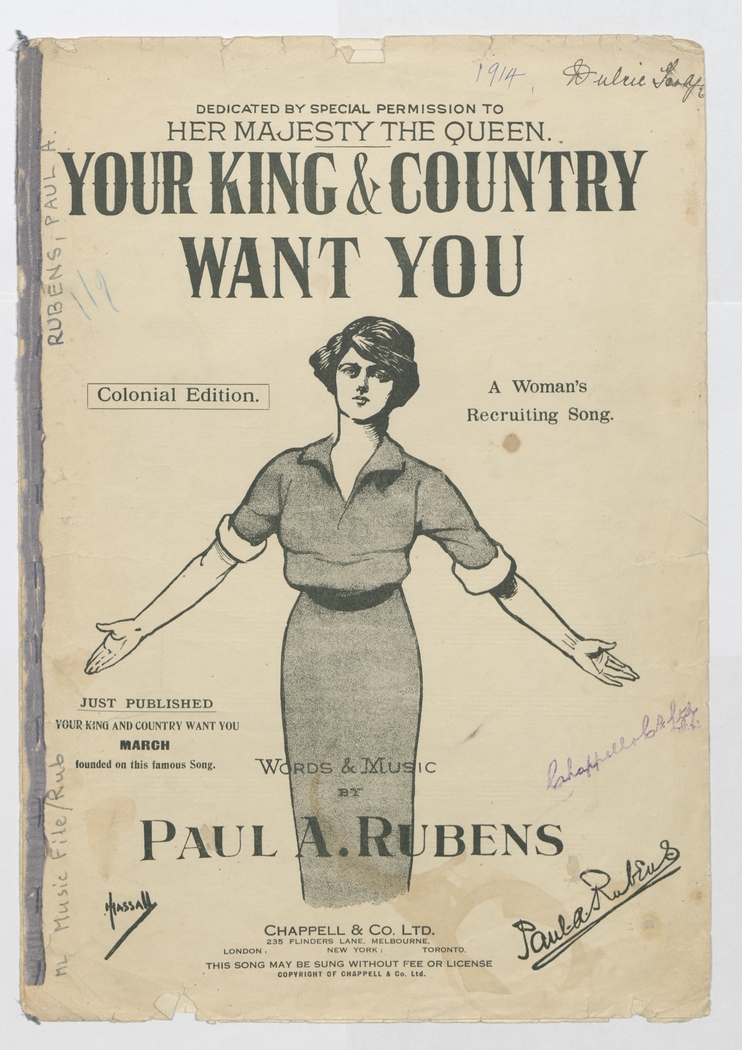

[media]When the war broke out Australia was in the midst of an election campaign. Both sides pledged support for Britain and the Australian Labor Party won the election convincingly. Because existing militia forces were unable to serve overseas, men were asked to volunteer for an Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Recruiters wanted men of British or European background, in good health, aged 19 to 38 and at least 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 metres) in height. The age limit was later extended to 45 to extend eligibility to many men who had fought in the Boer War. There was enthusiastic public support and thousands flocked to join up. Volunteers offered themselves from a wide variety of motives. The pay was good in a time when jobs were hard to find, meals and uniforms were provided, and the government would pay to send you across the world. It was seen as a great adventure, not to be missed. Patriotism was also a very significant motive – the duty to help Great Britain in her hour of need resonated with many Australians, the overwhelming majority of whom were either British by birth or had British-born parents.

Within two weeks of the outbreak of war more than 10,000 men had applied to join up in Sydney alone. [2] Preference was given to experienced soldiers with either previous war service or membership of the CMF. Several hundred men were quickly formed into a battalion and on 18 August they marched through cheering crowds from Moore Park to Fort Macquarie and ferried to Cockatoo Island, where they awaited embarkation. [3]

The flood of volunteers was strong during 1914, both residents of Sydney and men from country areas. Many of the latter were already proficient marksmen which made them valuable recruits. Some came to Sydney at their own expense but, until military recruiting depots were established in major country towns, local police officers and mayors were used as recruiting officers, with the authority to issue warrants for free travel to Sydney to men wishing to enlist who met the minimum requirements.

At the beginning of 1915 recruitment in New South Wales alone was running at about 1,000 per week but the rate gradually declined as the initial excitement wore off and there was little news reported about the activities of the first Australian contingent, who were in training in Egypt.

[media]The AIF took part in the Allied forces' Gallipoli landings, designed to open the Dardanelles for the Allied navies. Casualties were high but despite this the news of the Gallipoli campaign led to an immediate increase in enlistments. The need for replacement soldiers stirred the patriotism of many, despite the obvious dangers. Some men enlisted to avenge the loss of a brother or friend; some must have been influenced by letters from men at Gallipoli that were published in the newspapers. For example, Private Pryke from Redfern wrote,

we want more men. Some of the chaps have been here for months, and should be relieved for a short spell. If we are to wipe these Turks and Germans off the map, we must have more men... [4]

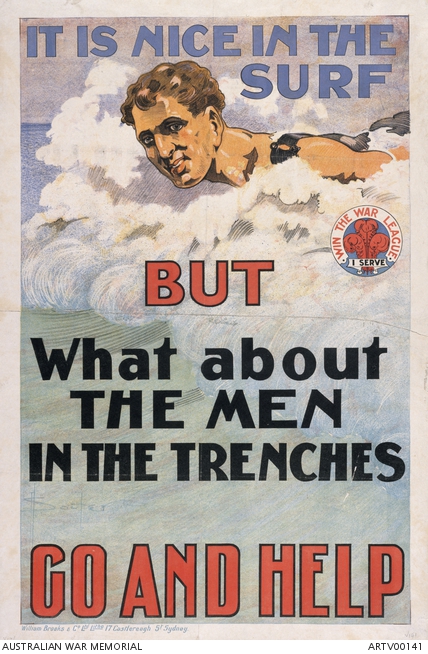

Declining enlistments

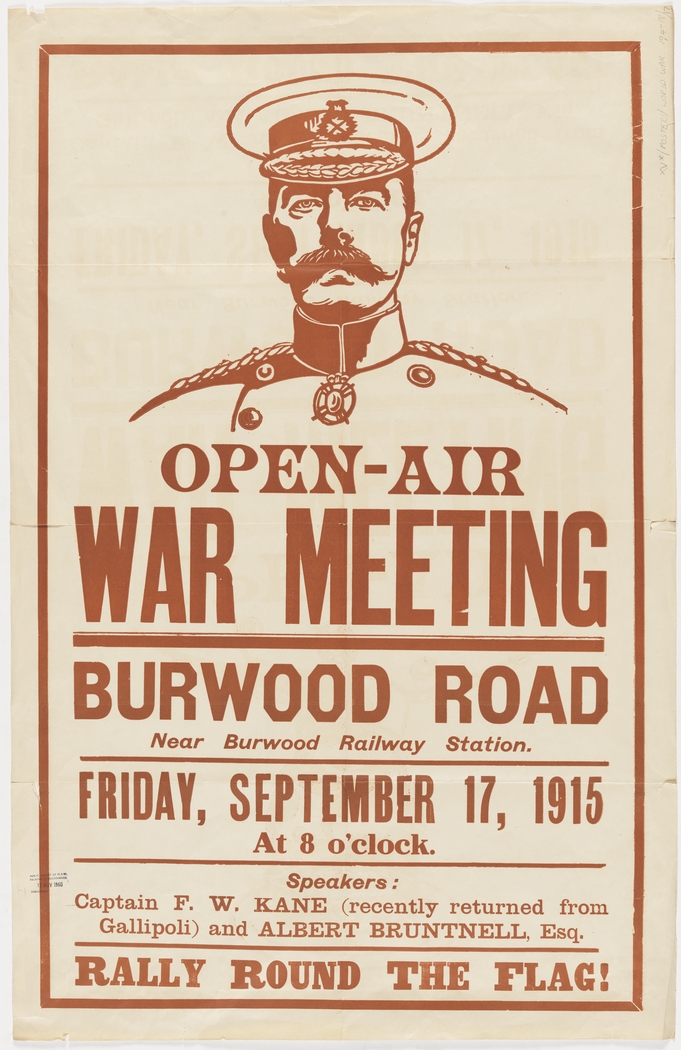

[media]From September 1915 enlistments steadily fell off, then spiked in January 1916, the month after the evacuation of Gallipoli. Throughout 1916 enlistments declined fairly steadily as conditions on the Western Front became better known. While the high casualty rates on the Western Front increased the pressure for more reinforcements to cover the losses, they must also have deterred some men from coming forward. Joining the AIF was no longer an adventure. As well as reinforcements, Prime Minister Hughes had promised more men for a planned big push for Allied victory.

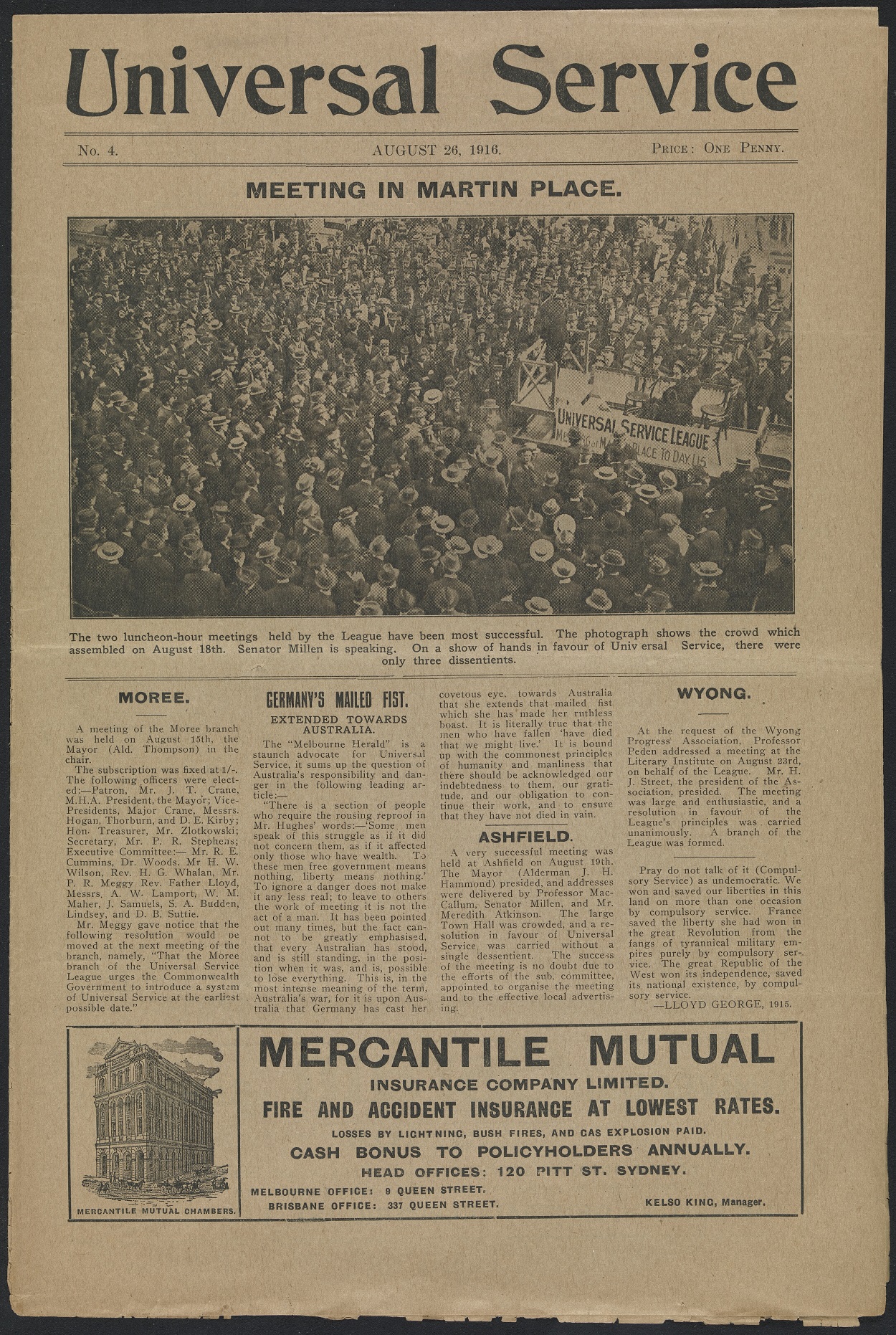

Recruiting meetings and rallies organised by State and local authorities were held in Sydney and suburban halls and on street corners, particularly at lunchtimes and in the evenings when working men would most easily be able to attend. The Sydney Chamber of Commerce, the Employers' Federation and other representative bodies encouraged their members to sponsor lunchtime recruitment meetings of men at their places of work. Some employers offered to supplement workers' army pay so they would not lose financially by volunteering. [5] Sporting bodies asked local clubs to use their annual meetings for recruiting and religious leaders asked the ministers of local churches to emphasise recruiting and patriotism in their sermons.

[media]In New South Wales, 30 July 1915 was designated 'Australia Day' in which cities, suburbs and towns held parades, concerts, sporting events and other activities designed to boost recruiting and to raise funds for sick and wounded soldiers. A large recruiting meeting was held at the Exhibition Building in Prince Alfred Park on 31 July as an introduction to a recruiting drive focussing on 4 August, the first anniversary of the outbreak of war. [6] The main recruiting depot at Victoria Barracks was supplemented by others in the Sydney Town Hall and the Board of Health, the latter open in the evenings for those men who could not attend during the day. [7]

Even the makers of patent medicines did their best to improve enlistment statistics. Clements Tonic published advertisements quoting a letter from a sergeant at Liverpool Army Camp:

When I say that Clements Tonic has helped swell recruiting figures I am only giving credit where credit is due. Among the "cream of the nation's manhood" which is answering the Empire's call today is the usual percentage of nerve-strained men from the city offices who would certainly have failed to pass the medical test had it not been for the wonderful restorative qualities of your medicine … [8]

Recruiting marches

An unusual, but productive, feature of the recruiting effort was the almost spontaneous organisation of so-called 'snowball' marches from country towns to Sydney during late 1915 and early 1916. The first started in Gilgandra in October 1915 when about 25 local men decided to march to Victoria Barracks in Sydney to enlist and to try to encourage others to join in along the way. They called themselves the 'Cooees' and were feted in each town they passed through. Their number had swelled to 263 by the time they reached Sydney, where they received an enthusiastic reception. [9] Between November 1915 and February 1916 at least eight such 'snowball' marches made their way to Sydney: Gilgandra 'Cooees' (263 men), South-west 'Waratahs' (117), Wagga 'Kangaroos' (213), North-west 'Wallabies' (180), 'Men from the Snowy River' (142), Tooraweenah 'Kookaburras' (100), the 'North Coasters' (220) and the Middle west 'Boomerangs' (201). [10]

The first conscription referendum

Voluntary enlistment had supplied the AIF with more than enough men for the first year or so of the war but heavy casualties in the trenches of Europe outpaced enrolments. Despite every effort and appeal the number of men coming forward to volunteer in 1915 did not come even close to the numbers needed to maintain the country's forces at an operational level. Among all the armies fighting in the war, the AIF was the only all-volunteer army, and clearly the voluntary system was proving inadequate. WM Hughes (who succeeded to the office of Prime Minister in October 1915) came under considerable pressure from the British government to introduce conscription and he was also being pressured by a powerful local pro-conscription body, the Universal Service League formed in September 1915. The League's president was Professor TW Edgeworth David of the University of Sydney. The large number of vice-presidents included other university professors, the Premier WA Holman and senior parliamentarians, Archbishops JC Wright (Anglican) and Michael Kelly (Roman Catholic), the Lord Mayor Ald RW Richards, business leaders and others with political and community influence. [11]

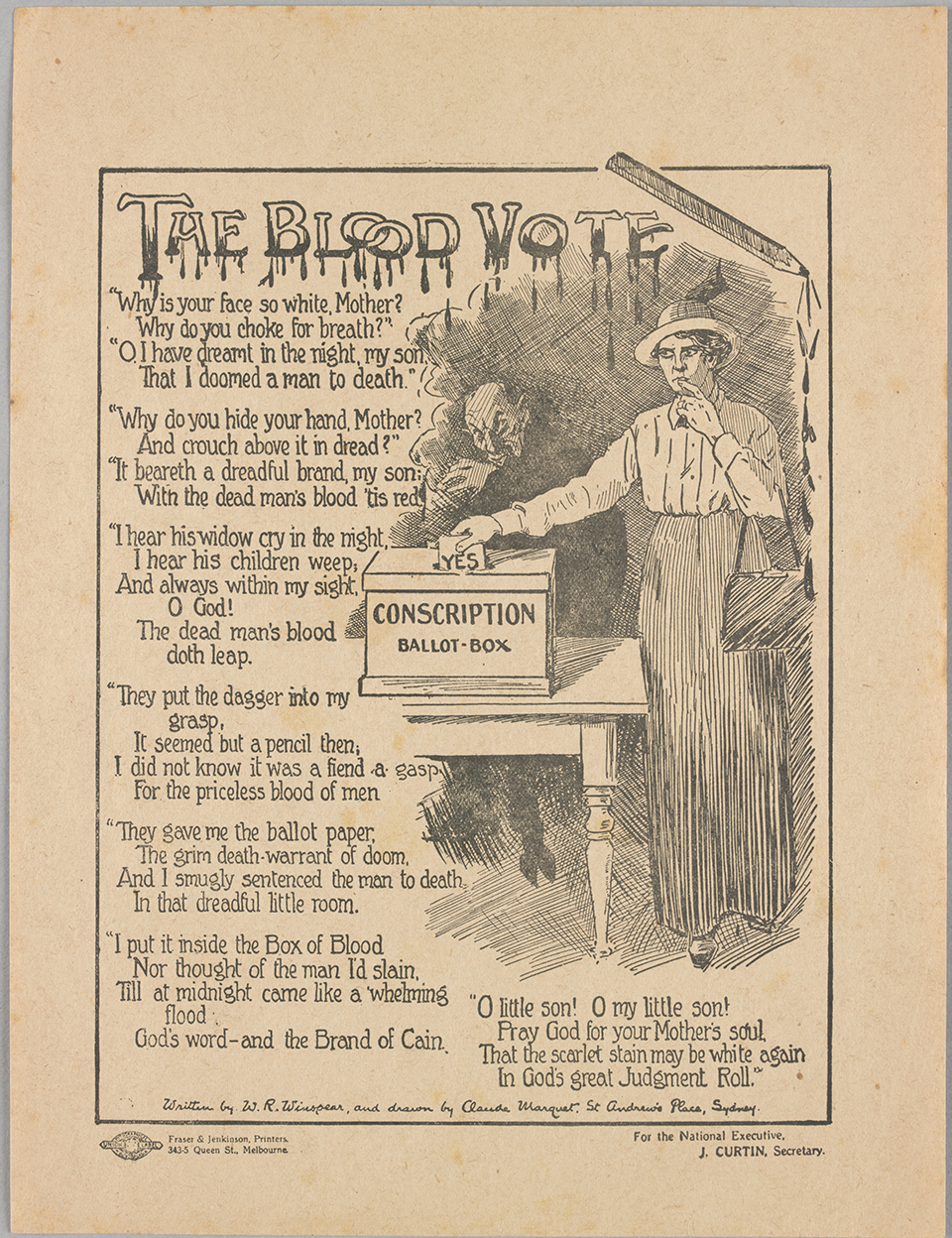

The League, in turn, was opposed by many in the labour movement, the official policy of which was to oppose conscription. [12] An Anti-Conscription League was promptly formed at a meeting in the Sydney Trades Hall with leadership from various trade unions and socialist organisations. [13]

In April 1916 the first anniversary of the Anzac landing at Gallipoli inspired a huge upsurge of patriotic sentiment. Marches and other commemorations were successfully used as recruiting devices and to collect donations to provide comforts for those at the front.

Enlistments increased for a while, but in July 1916 Allied losses at the Somme River were severe. More than 27,000 Australians were killed or wounded and although any dissent from patriotic support for the war was almost considered treason, an increasing number of Australians began to question the reasons for their country's continued involvement. The British War Council warned Hughes that, given recent losses, the AIF could not be kept at full strength unless conscription was introduced. Hughes knew that to try to impose conscription by regulation under the War Precautions Act would split the Labor Party whose policy opposed conscription and anyway Labor had a decisive majority in the Senate, which would surely disallow such a regulation. He decided to put the question to the people in a referendum.

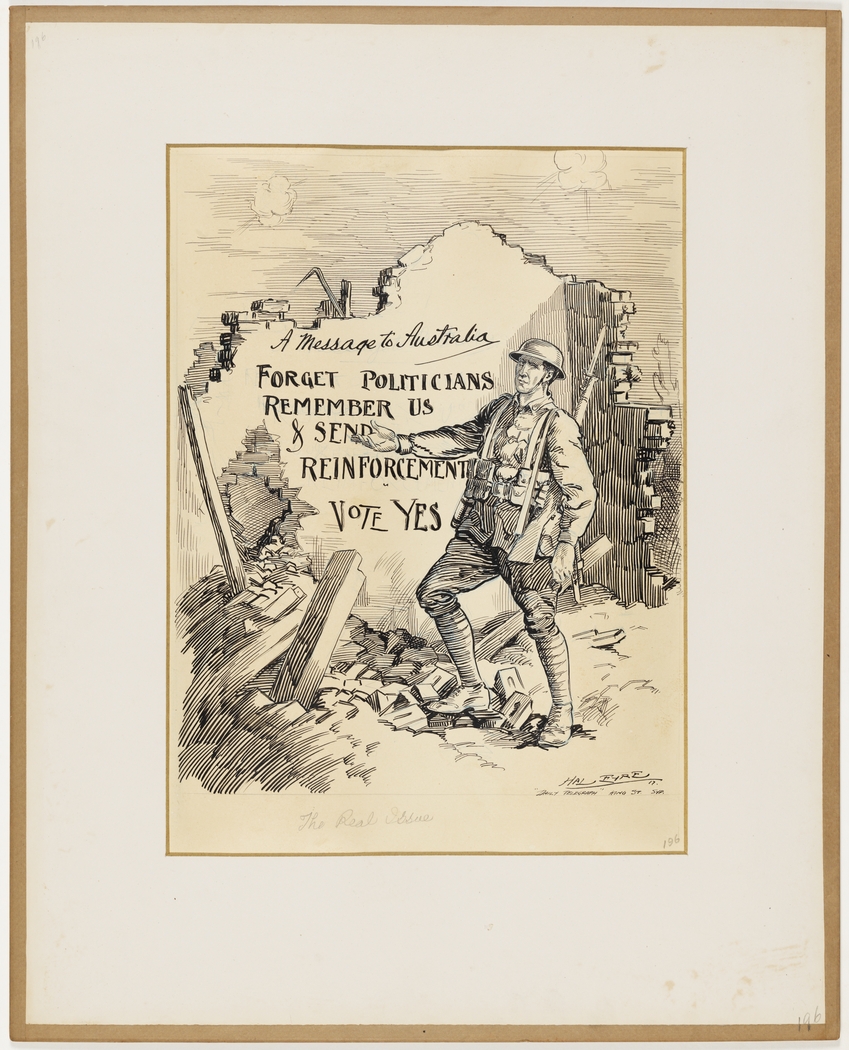

[media]A spirited and divisive campaign occupied most of September and October 1916. Conservatives generally favoured conscription – England had it, so should Australia. It generally enjoyed support in parliament, the press and the Protestant churches. Farmers opposed conscription because they needed men to grow food and wool. The labour movement was against it, fearing that cheap labour would be imported to replace the conscripts and thus weaken the White Australia policy. War was seen as a form of exploitation of working men for the benefit of middle class imperialists. Enough lives had been lost already. The Catholic church took the side of the majority of its members who were working class.

[media]Hughes, who represented the seat of West Sydney had been expelled from the Labor Party in his home state of New South Wales for breaching the party's anti-conscription policy on 15 September 1916, opened the 'yes' campaign at Sydney Town Hall on 18 September with a rousing call for patriotism to rise above party politics in the defence of the nation and the Empire. [14] He seemed untroubled by having proclaimed in parliament the year before: 'In no circumstances would I agree to send men out of the country to fight against their will.' [15]

For the next six weeks both sides held spirited meetings and published exaggerated and emotionally stirring posters and advertisements. Women, as mothers and wives, were a particular target of each side's appeals – mothers should resist sending their sons to kill other mothers' sons; women should vote in favour of stopping the murderous Hun raping women and slaughtering children, and so on. The mainstream press was firmly on the 'yes' side and the labour movement firmly on the other. The playing field was not exactly level because regulations under the War Precautions Act, prohibiting anyone from interfering with recruiting or criticising the methods used to wage the war, were used against speakers, journalists and others who too strongly espoused the anti-conscription cause. Hughes's final campaign speech from the back of a lorry in Sydney was not lacking in emotional exaggeration:

Go to the booth, and by the dagger of your votes destroy or help destroy that monster of despotism which, if not destroyed, will destroy you. (Applause). [16]

[media]The vote was very close: Yes gained 1,087,557 votes (48 per cent) and No 1,160,033 (52 per cent). Not only had Hughes lost but by calling the referendum and campaigning for a 'yes' vote he had split and severely weakened the Labor Party. On 14 November 1916, Hughes took about half the federal parliamentary party and formed the National Labor Party, which, in coalition with the Liberal Party, ensured him the numbers to continue as Prime Minister. This party merged into a new Nationalist Party in February 1917.

Alongside the splintering of the federal Labor Party the New South Wales Labor government was fatally damaged by the conscription crisis. The state party's 1916 annual conference resolved to oppose conscription abroad and that any conscriptionist candidates in the forthcoming elections would lose their endorsement. When Premier Holman and 17 others crossed the floor to vote with the opposition they were expelled. In November 1916 Holman formed a coalition with Charles Wade, the leader of the opposition Liberal Reform Party, to form the state branch of the Nationalist Party of Australia with Holman as leader. At the 1917 elections the Nationalists won a decisive victory.

The bitterness and division in the community caused by the referendum had reduced the flow of volunteers and although there were sufficient men for the time being there was no longer as much enthusiasm about volunteering, or about the war generally, as there had been. Physical standards were further loosened, and to increase the pool of applicants Aboriginal men, previously ineligible for enlistment, were accepted if they had one parent who was 'predominantly European'.

The second conscription referendum

[media]During 1917 the press and conservative groups continued to urge the government to adopt conscription. When Britain sought an additional Australian division for active service, Hughes knew that this could not be done without conscription and, despite the odds, he decided to hold another referendum. He launched the 'yes' campaign at Sydney Town Hall on 14 November 1917, restating many of the earlier arguments but emphasising that, in contrast to the 1916 proposal, this time conscription would only be used to make up any shortfall in voluntary recruiting targets and the government would use a lottery system to determine who would be called up. His speech was well received by the mainstream press. [17]

[media]The 'no' campaign was opened the next day in the Protestant Hall by Frank Tudor (Hughes's successor as Labor leader, who became Opposition Leader), whose arguments received a more critical evaluation. [18] Again the anti-conscriptionists were partly muzzled by wartime regulations and censorship. Supporters of both sides became almost hysterical in their propaganda, with those opposed referring to conscription as 'The Lottery of Death'. The bitter polarisation of the community would take years to heal.

Again the referendum was lost, with 1,015,159 Yes votes (46 per cent) and 1,181,747 No votes (54 per cent). This even more decisive vote against conscription closed the issue for the remainder of the war.

The final year

Recruiting continued to languish despite efforts to improve enlistments. Australia became increasingly war weary and the bitter recriminations from the conscription campaigns did not help. Recruiting marches and rallies were held in Sydney and elsewhere, perhaps the most unusual being that organised by Captain Ambrose Campbell Carmichael, MC, a former Labor politician who, in 1915, had successfully enlisted 1,000 rifle reserve recruits. Back in Sydney recovering from wounds he became Chairman of the State Recruiting Committee and organised a huge rally in Martin Place on 12 April 1918 with the objective of enlisting another 'Carmichael's Thousand'. Amid 'scenes of unbounded enthusiasm' he was again successful, although it was later revealed that the rally had been rigged and, with the collusion of army authorities, several dozen soldiers from Liverpool Camp had been issued with civilian clothes and ordered to attend the rally and be the first to 'volunteer' so as to enthuse others in the crowd. [19]

Of the 330,000 Australian volunteers who served overseas, 60,000 died and 160,000 were wounded, a two-thirds casualty rate. [20] Those who survived did not return to great victory parades in Sydney, mainly because they came back so irregularly during 1919 and 1920 whenever shipping was available. For most of them the great adventure had turned into a disappointment, for some a nightmare.

References

Dawes, JNI and LL Robson. Citizen to Soldier. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1977.

Robson, LL. Australia and the Great War 1914–1918: narrative and selection of documents. Melbourne: Macmillan Australia, 1969.

Robson, LL. The First AIF: a study of its recruitment 1914–1918. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1982.

Notes

[1] KS Inglis, 'Conscription in Peace and War 1911-1945' in Roy Forward and Bob Reece, Conscription in Australia (Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1968), 27

[2] LL Robson, The First AIF: a study of its recruitment 1914–1918 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1982), 28

[3] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 August 1914, http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/15530850, 12 and http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15530657, 14, viewed 2 June 2016

[4] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July 1915, 12

[5] For example, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 October 1915, 17

[6] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 August 1915, 9

[7] Sydney Morning Herald, 9 August 1915, 10

[8] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 November 1915, 7

[9] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 November 1915, 9, 19–20

[10] LL Robson, The First AIF: a study of its recruitment 1914–1918 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1982), 58. LL Robson, Australia and the Great War 1914–1918: narrative and selection of documents, (Melbourne: Macmillan Australia, 1969) Document 35

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 11 September 1915, 17

[12] For example, Australian Worker, 16 September 1915, 3

[13] Sydney Morning Herald, 24 September 1915, 10

[14] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 September 1916, 8, 9–10

[15] Australian Worker, 27 July 1916, 17

[16] Sydney Morning Herald, 28 October 1916, 14

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 November 1917, 6, 7–8

[18] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 November 1917, 6, 7–8

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 April 1918, 14. LL Robson, The First AIF: a study of its recruitment 1914–1918 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1982), 193–4

[20] LL Robson, The First AIF: a study of its recruitment 1914–1918 (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1982), 202–3

.