The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Theatre

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Theatre

[media]The transport vessel Scarborough was the site of the first recorded colonial theatrical performance. On 2 January 1788, 17 days out from landfall at Botany Bay, the convicts 'made a play and sang many songs'. [1] Over a year later, at the settlement, George Farquhar's well-known The Recruiting Officer was performed on 4 June 1789 as part of the officially sanctioned celebrations of the birthday of King George III. [2]

The first theatres

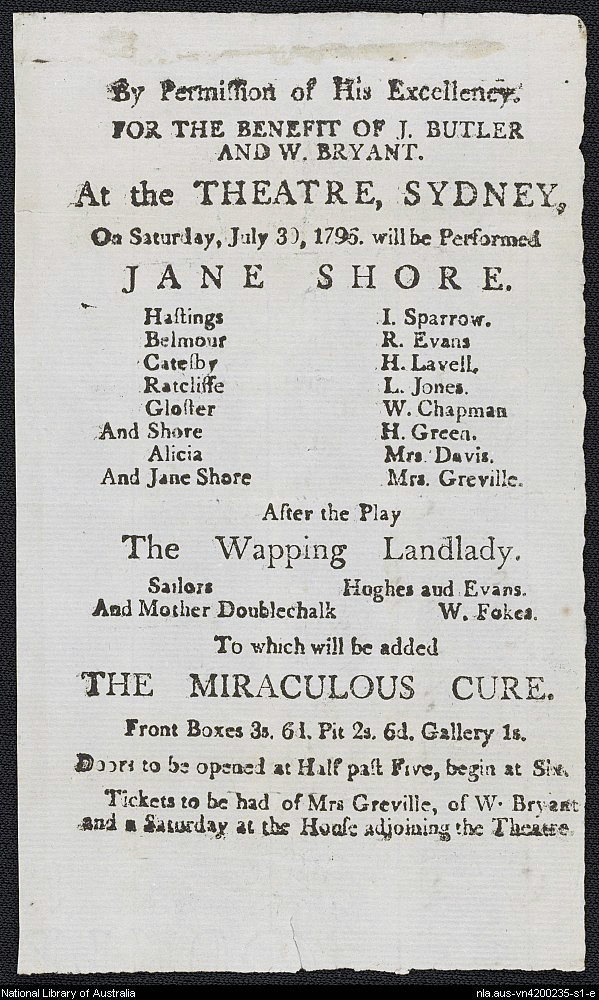

Any theatrical venture in the colony had to have the Governor's permission and not all governors were accommodating, but convict theatres soon appeared. [media]By 1794, there was a makeshift theatre operating in Sydney, and in 1796, Robert Sidaway, an emancipated convict, formally opened a short-lived public playhouse, known simply as The Theatre. It was probably on the edge of The Rocks area in Windmill Row, later renamed Prince Street, an area later buried under the earthworks for the Sydney Harbour Bridge in the 1930s. [3]

Commercial theatre arrives

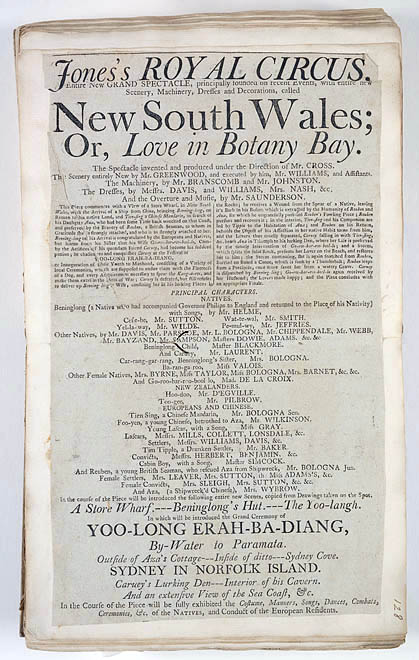

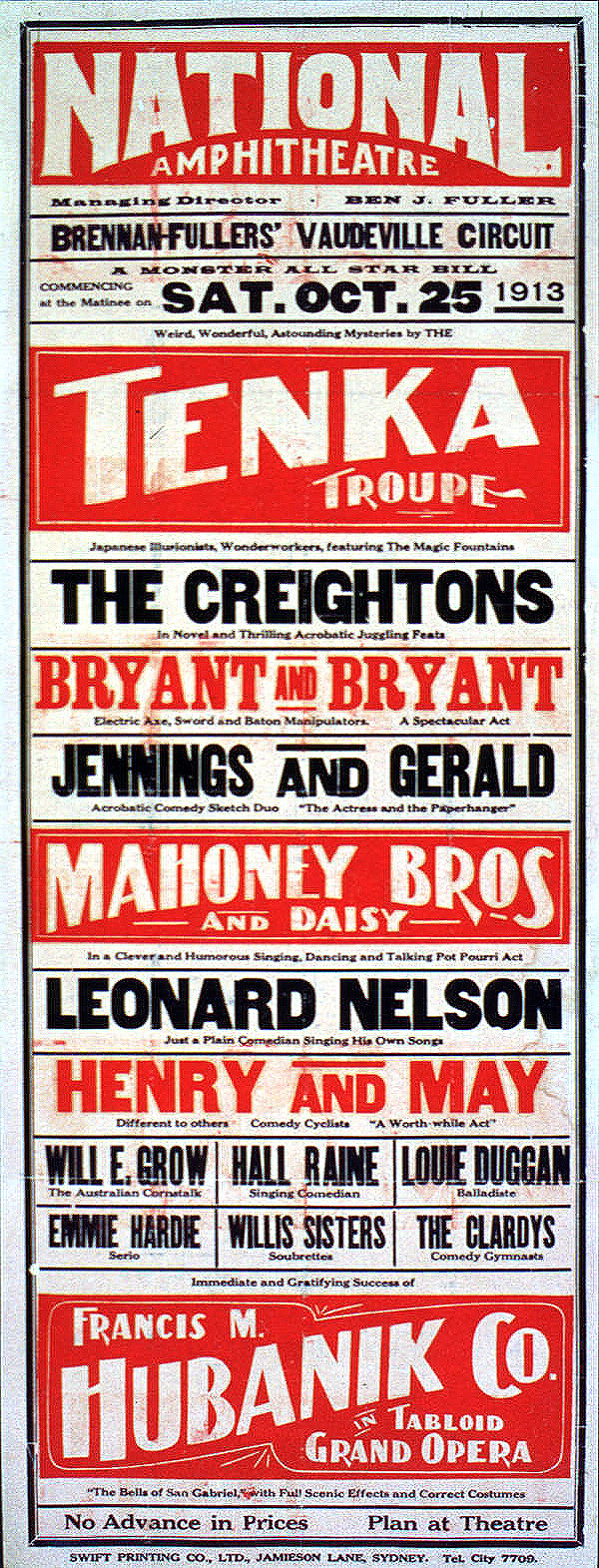

After 40 years of spasmodic performances at the governor's pleasure, a commercial theatre finally emerged, when entrepreneur Barnett Levey won a long battle for permission to open a licensed theatre in 1832. Other businessmen attempted to follow his lead in building theatres, and 'musical nights' also began in Sydney in the late 1830s as combination of grog shops and variety houses. The economic uncertainties of a small and isolated community, however, inhibited expansion until, in the 1850s, both population and prosperity were briefly stimulated by gold discoveries. There was a short boom in theatre building, and Sydney was visited by international touring companies. [media]Another lull followed, until the prosperity and nationalist confidence of the late 1870s and 1880s again stimulated both theatre building and the emergence of entrepreneurial chains. The pre-eminent and longest lasting of these was Williamson, Garner and Musgrove which, after complex business rearrangements, emerged in 1905 as JC Williamson's and continued to operate until the 1970s. But there were also extensive touring circuits and theatres including those built by Harry Rickards and William Anderson, and a bit later by George Marlowe, J & N Tait, Ben Fuller, Harry Clay and others who successfully presented melodrama, vaudeville and musicals to large audiences.

The twentieth century

Expansion was again limited by depression in the 1890s. Nonetheless in the new century, despite the growing popularity of cinema and the hiatus in business life brought by World War I, live theatre remained a viable part of the entertainment industry. In 1900 there were seven major theatres operating in Sydney and by the late 1920s this had expanded to ten. JC Williamson's dominated the Sydney theatre with mostly imported material, but melodrama, vaudeville and revue were also popular with audiences. Following the European example, amateur 'little theatres', presenting modern works, also emerged.

Then the Great Depression hit the commercial theatre. [media]Economic depression combined with the effect of imported cinema, recording techniques, entertainment taxes led to the partial demise of the chains and many theatre sites were converted to cinemas or shops. By the end of 1935 there was no major drama touring company and only two commercial theatres remained open in Sydney.

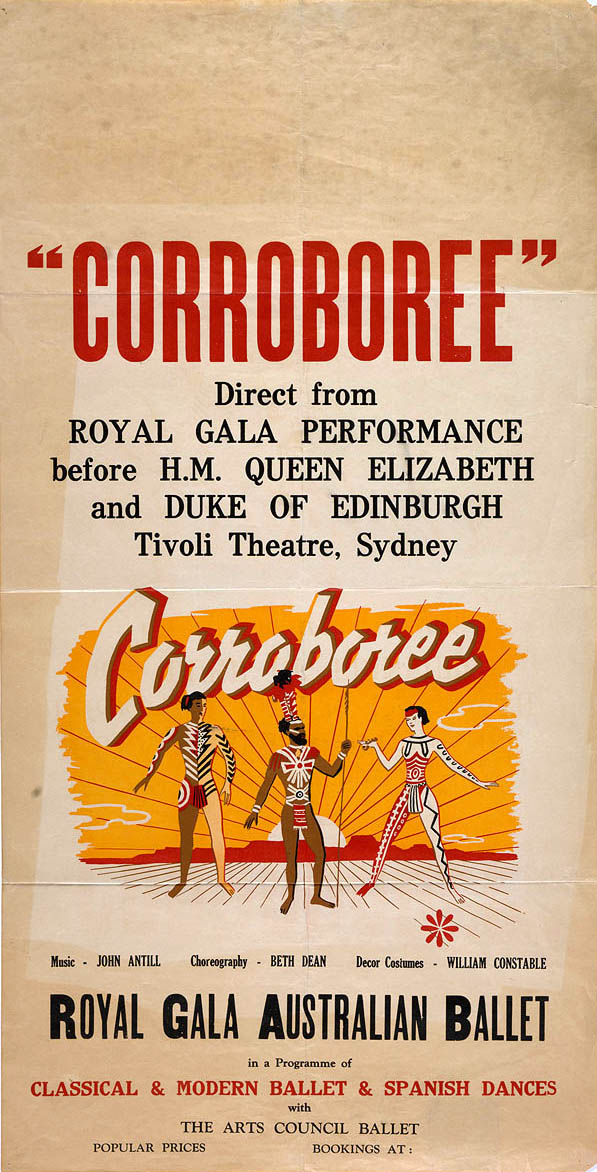

[media]Following World War II, a spasmodic and erratic revival of live theatre emerged, usually initiated by Williamson's, either through overseas touring companies or revivals of musicals. There were complex factors at work here including cultural initiatives aimed at nationalist unity and Imperial image-making, both of which underlay much of the philosophy and activity accompanying postwar reconstruction.

Other influences were the possibilities for commercial profit, the emergence of a role for subsidised theatre, and university engagement in theatre studies and in operating theatre companies. [media]With the establishment of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust in 1954, the innovative principal of government support for the arts, including some theatres, was instituted.

[media]The later 1950s and 1960s also saw the evolution of an alternative theatre, which aimed to present Australian plays. Re-emergent nationalist sentiment inspired theatre that reflected images of Australians to Australian audiences. [4]

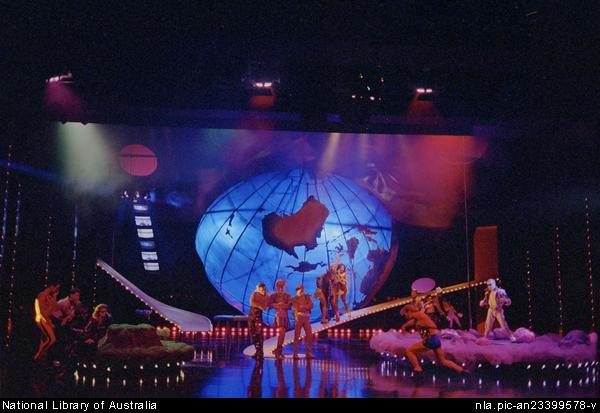

[media]Over the last 40 years, these influences have led to dual systems of theatrical presentation, permanent state or quasi-state theatre companies, such as the Sydney Theatre Company, on the one hand, and commercial entrepreneurs using city venues, often for large scale musical spectaculars, on the other.

The influence of Georgian theatres

Historically, the spaces used for theatrical performances have been very varied, ranging from open paddocks to temporary platforms, town squares and palaces. But the European settlers at Sydney Cove in the late eighteenth century brought with them the style of British theatre that they knew – the Georgian theatre. This has influenced the style of theatres in Sydney until recent years.

The Georgian plan was a rectangular or horseshoe-shaped auditorium divided approximately in half. The audience area consisted of a 'pit', which was originally standing room floor space and later had benches and some seats, a series of elevated boxes around the walls, and a gallery above. The other half of the rectangle was a raised performance area – a stage with an ornate proscenium arch and a forestage, initially with side doors and later, as the forestage decreased, with tiered boxes.

In the Georgian theatre, settings were changed using a system of grooves and tracks by which flats, screens and border pieces could be moved in and out from the wings. These flats, which were rectangular panels made of material stretched over a wooden frame, were of rigid construction, while the screens and borders could be flexible and of various shapes. Sets could not be 'flown', that is lifted above the stage area. This innovation, a result of the desire for a 'box' set as a realistic representation of actual living space, did not come into general use until the 1890s. New technology for lifting and lowering settings allowed designers to create spectacular scenes but presented a considerable challenge to architects and builders in modifying existing theatres to obtain space above the stage.

Up until the end of World War I, playhouses were increasingly ornamented in Regency style. The fashion for decoration reached its peak in the 1920s, particularly in the designs of the leading architect Harry E White. [media]Much of this work has been destroyed, but the style can still be seen in the interior of the Capitol Theatre.

Modernist theatre buildings and 'found spaces'

Late in the 1920s, a reaction against this fashion began to emerge, with modernists arguing that decoration distracted the audience from the action on stage. Before a changing style could evolve, however, the depression of the 1930s and then World War II effectively ended theatre building in Sydney until the late 1950s. With the revival, performance spaces were often in small, usually university-based theatres, where modernist design came to prevail. Examples include the interior design of the now derelict Empire Theatre, but it was frequently demonstrated in 'found spaces'. In a revival of an old theatrical practice, the Nimrod Theatre (formerly a factory), the Old Tote (formerly a totalisator or off-track betting facility), Jane Street (formerly a church) and much later the Sydney Theatre Company's Wharf theatres were all created in the fit-up tradition of using existing space. [5]

In the early nineteenth century in New South Wales, few theatres were purpose-built and the colonists were adept at creating fit-up performance spaces in available large areas. These saloons or assembly rooms were usually in hotels. When a theatre developed from the rooms, though it may have become the largest part of the existing hotel building, it was behind the tavern and bars on the street front. [media]Levey's Theatre was in his hotel, and the later Theatre Royal, built in 1855, was fronted by a two-storey hotel. [6] This combined use of space continued until 1882, when legislation was passed prohibiting the association between theatres and hotels. Rules, however, can be circumvented, and the link between hotels and theatres remained a feature of Sydney theatrical life. The first Her Majesty's, built in 1887, was still behind the ornately ornamented facade of a five-storey hotel, and it was not until 1912 that legislation required that patrons leave the theatre and reach the bar by a separate entrance.

The foyers of Sydney's nineteenth-century theatres were little more than lobbies, since the space was not required for refreshment or socialising, which went on in the hotel. When the theatres went 'dry' in 1916 with the wartime introduction of six o'clock closing for hotels, the legacy of small and inadequate foyers remained with Sydney theatres. Relaxation of the liquor laws in the 1970s saw the reintroduction of bars and an increased foyer area, but by then most of Sydney's nineteenth-century theatres had been destroyed. [7]

The experience of theatre

Modern Sydney theatre-goers are accustomed to numbered seating in comfortable chairs with armrests, in an auditorium with wide aisles conforming to strict fire regulations. This was not so in nineteenth-century theatres. These could be, and were, packed with people. Seats were not numbered, and all but the most expensive seating was bench style. Managers crammed people into aisles and makeshift seating to increase the holding capacity. They allocated each audience member less than half the space required today. Audience capacity figures for early theatres need to be interpreted with this in mind. [8]

[media]Until the 1890s the auditorium was never completely dark, so audiences went to the theatre to be seen by others as well as to see the players. Performances in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century were usually lit by candles, which were used both to generate onstage light and to gain a specific effect from footlights, positioned across the front of the stage. Limelight, a light created by a combination of chemicals, was also used both for stage lighting and for creating special effects. Gas lighting, which came into general use in the first half of the nineteenth century, improved the flexibility of theatre lighting but this, like candles, could not be completely turned off without arduous relighting. Control of light, and the familiar darkened auditorium, only became possible with the widespread use of electric lighting, which first came into use in the Sydney theatres in the 1890s.

Theatre names

Sydney entrepreneurs adopted a number of traditional theatre names, often copied from those in Britain. Names such as Royal, Empire, Gaiety, Princess, Prince of Wales and Adelphi, among others, were all in use in nineteenth-century Sydney, reflecting the theatrical traditions of England, and this practice continued over the years. [media]Two of these titles, the Theatre Royal and the Capitol, are still in current use in Sydney.

There was nothing requiring consistency in the naming of a theatre. Theatrical entrepreneurship was a risky business. Either bankruptcy or business success could see a theatre owner and/or builder end an association or move from one site to another, taking the old name, reviving a former name or adopting a new one.

These theatres, also, were very vulnerable to fire. Canvas, paint, candles, chemicals and gas lights were and are a dangerous combination, and safety curtains, brick fire walls and running water weren't even a possibility until the early twentieth century. Sydney theatres, therefore, were quite often destroyed by fire and rebuilt, or extensively modified, sometimes under the old name, sometimes under another one.

Going to the play

From European settlement until the 1970s Sydney's theatres drew heavily for their repertoire on the British theatrical tradition. Over the nineteenth century there was a particular emphasis on, and an audience fondness for, works derived from Imperial popular culture, such as melodrama, pantomime, minstrelsy, music hall and spectacular entertainment. There was always a small amount of local playwriting, which increased during periods of optimistic nationalism such as the 1840s and in the 1870s and 1880s, and some of imported material was always localised. This was particularly true of pantomime, but many melodramas were also given local settings and incorporated colonial situations, jokes and characters. Nonetheless official censorship which necessitated, for much of this period, a licence from the Colonial Secretary for performance to take place, limited the development of a colonial style. [media]Topics which were directly relevant to the colonial experience, such as convict life, relations with Aboriginal communities or bushranging, were seen until the early 1930s as unacceptable in 'polite society'.

'High culture', including productions of Shakespearean plays and works of the British theatrical tradition, was the province of touring 'star performers' either from Britain or America. [media]From the first tours of the mid-nineteenth century, with performers such as Charles and Ellen Kean, Gustavus Brooke and Walter Montgomery, to the Old Vic tour of 1948 headed by the Oliviers and lesser luminaries who followed, overseas stars were seen as bringing international validation to a colonial sense of cultural self-worth. The performers were greeted with country-wide adulation.

Just as a change emerged in the style of theatre building in the 1970s, as a result of complex social factors, so the focus and style of the repertoire of Sydney's theatres changed as part of a continuing process. Theatre is an evolutionary craft. It is both an initiator of cultural change and a reflector of it.

References

Katherine Brisbane (ed), Entertaining Australia: an illustrated history, Currency Press, Sydney, 1991

Eric Irvin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre 1788–1914, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1985

Robert Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia 1788–1840, Currency House, Strawberry Hills NSW, 2002

H Love (ed), The Australian Stage: a documentary history, University of New South Wales Press in association with School of Drama, University of New South Wales, Kensington NSW, 1983

P Parsons (ed) with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia, Currency Press in association with Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 1995

Richard Waterhouse, From Minstrel Show to Vaudeville: The Australian Popular Stage 1788–1914, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1990

John West, Theatre in Australia, Cassell, Stanmore NSW, 1978

Notes

[1] Eric Irvin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre 1788–1914, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1985, p 272

[2] Eric Irvin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre 1788–1914, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1985, p 273. For two entertaining, fictionalised accounts of this production, see Thomas Keneally, The Playmaker Hodder and Stoughton, Sydney, 1987, and the dramatisation of this work, Timberlake Wertenbaker, Our Country's Good, Methuen, London, 1989, presented at the Royal Court Theatre, London and the Sydney Theatre Company, Sydney, July 1989

[3] Robert Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia 1788–1840, Currency House, Strawberry Hills NSW, 2002, pp 27–56 and 137–78

[4] H Love (ed), The Australian Stage: a documentary history, University of New South Wales Press in association with School of Drama, University of New South Wales, Kensington NSW, 1983

[5] P Parsons (ed) with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia, Currency Press in association with Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 1995, pp 566–70

[6] Eric Irvin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre 1788–1914, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1985, pp 160–61, 272–94

[7] P Parsons, (ed) with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia, Currency Press in association with Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 1995, pp 589–95

[8] P Parsons, (ed) with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia, Currency Press in association with Cambridge University Press, Sydney, 1995, pp 65–69

.