The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Lidcombe

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Lidcombe

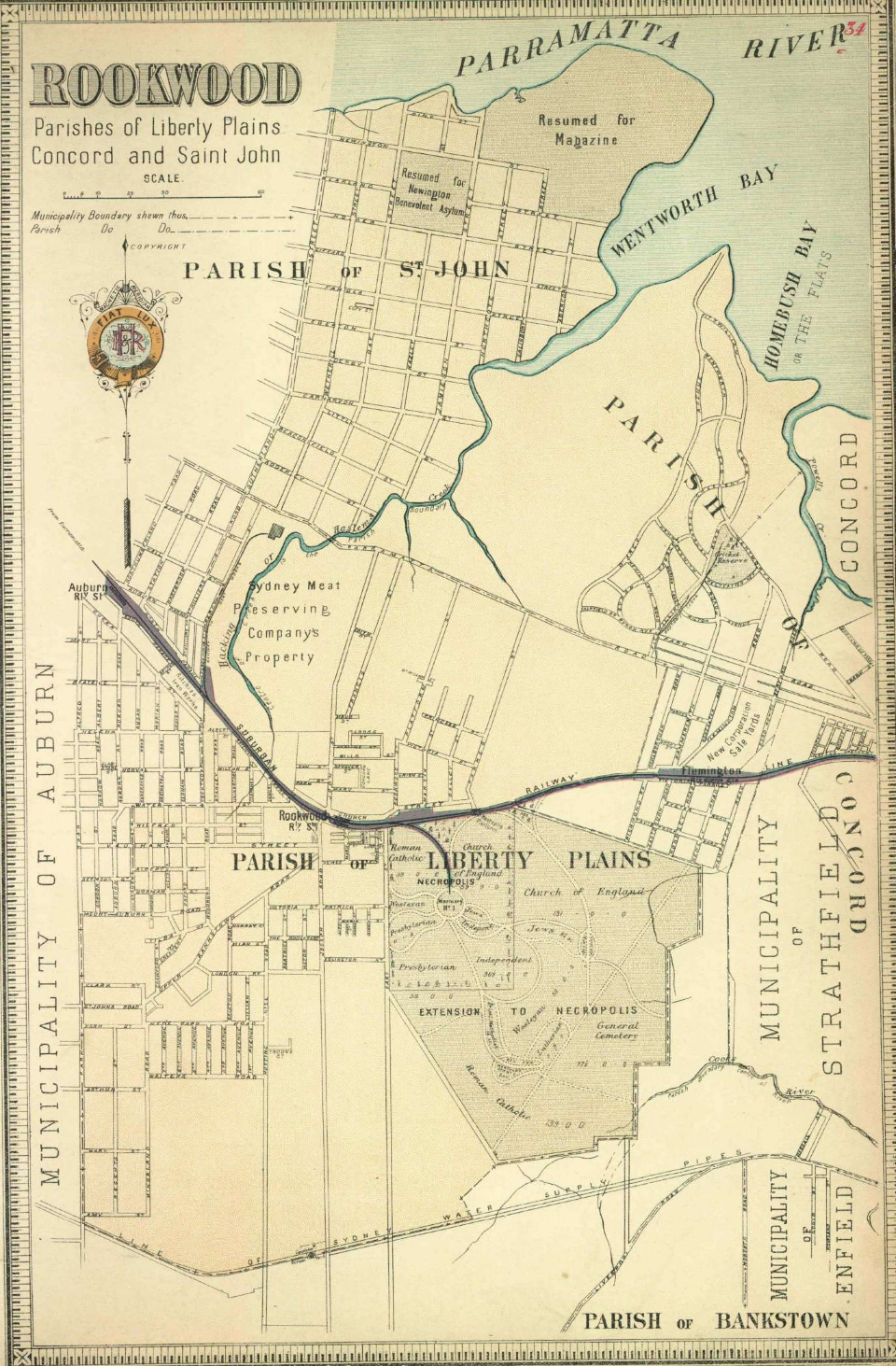

Lidcombe, in Auburn municipality and on the traditional lands of the Dharug people, centres upon the railway station and a small shopping centre. It extends north to Parramatta Road and east to Rookwood Cemetery. On the western and southern boundaries it merges into Auburn and Berala. The land is fairly flat, but generally slopes down towards the Parramatta River.

Early visitors and settlers

An exploring party rowing up the river reached Homebush Bay on 4 February 1788, coming close to the area known today as Lidcombe. [1]

While the river remained the main means of transport, a track from Sydney to Parramatta developed early in the 1790s, running about a mile (1.6 kilometres) south of the current Parramatta Road, crossing Duck River roughly where Mona Street crosses today. Parramatta Road was laid out about 1797, under the direction of the surveyor-general Augustus Alt. [2] Private coaches ran along this road, but a regular service did not appear until John Raine's began in 1823. Coaches ran until the railway started to take away their passengers from 1855. [3] To service these travellers, inns were established along Parramatta Road.

At the time of the 1828 census, the area that became Lidcombe lay within the District of Parramatta and partially in Concord. Land was granted to free settlers and to ex-convicts. Most grants were small, often only 30 to 100 acres (12 to 40 hectares), and were awarded to people such as the government official Edward Gould, the merchant Henry Marr and John O'Donnell. Larger grants went to prominent merchants and officials, such as Joseph Hyde Potts, who was given 410 acres (166 hectares).

By 1828, there was a thin spread of settlers over the area. Those that can be identified as living in the present area of Lidcombe include Ann Curtis, with a daughter and a single servant, and Samuel Haslem, with his wife, son and two assigned servants. [4]

The original vegetation of the area was open forest of grey box, ironbark and stringy bark, with woollybutt red gums dominating. Many settlers were slow to clear their land. J and W Haslem had cleared a mere 8 per cent, and Samuel Haslem only 50 per cent, in 1828. Many other grants were unoccupied, so that large areas were still covered with their original vegetation.

Over time, fires reduced the tree cover. During a huge fire about 1856, Mrs Greatrex and her family sheltered under the railway bridge. She was the daughter of Edmund Keating, and spent most of her life (1847–1935) in Lidcombe. [5] One huge fire in the 1860s threatened the home (now the corner of Nicholas Street and Bachell Avenue) of James Belcher, a government forestry officer, causing him to bury a box of gold sovereigns. It was not found until 18 months later, when a field was being ploughed. [6]

St Ann and St Joseph

Father John Joseph Therry, the first Roman Catholic priest in New South Wales from his arrival in May 1820, conceived of a religious centre in the town of St Ann, near Cook's River. St Ann came to fruition in a modest way, and its church still remains.

Although there were no overt plans, Therry's development of the town of St Joachim's near Haslems Creek (now spelt Haslams) had the effect of creating a line of Catholic settlement. He purchased Patrick Kirk's grant in 1831, and most of George Sunderland's grant, as the basis for the town. [7] The railway to Parramatta bisected the land at Haslams Creek, and the town was arranged on either side of the line with streets named after various saints. [8] In his will, Therry left instructions to devote the proceeds of the sale of land at St Ann to the church there, but none regarding the Haslams Creek land. [9]

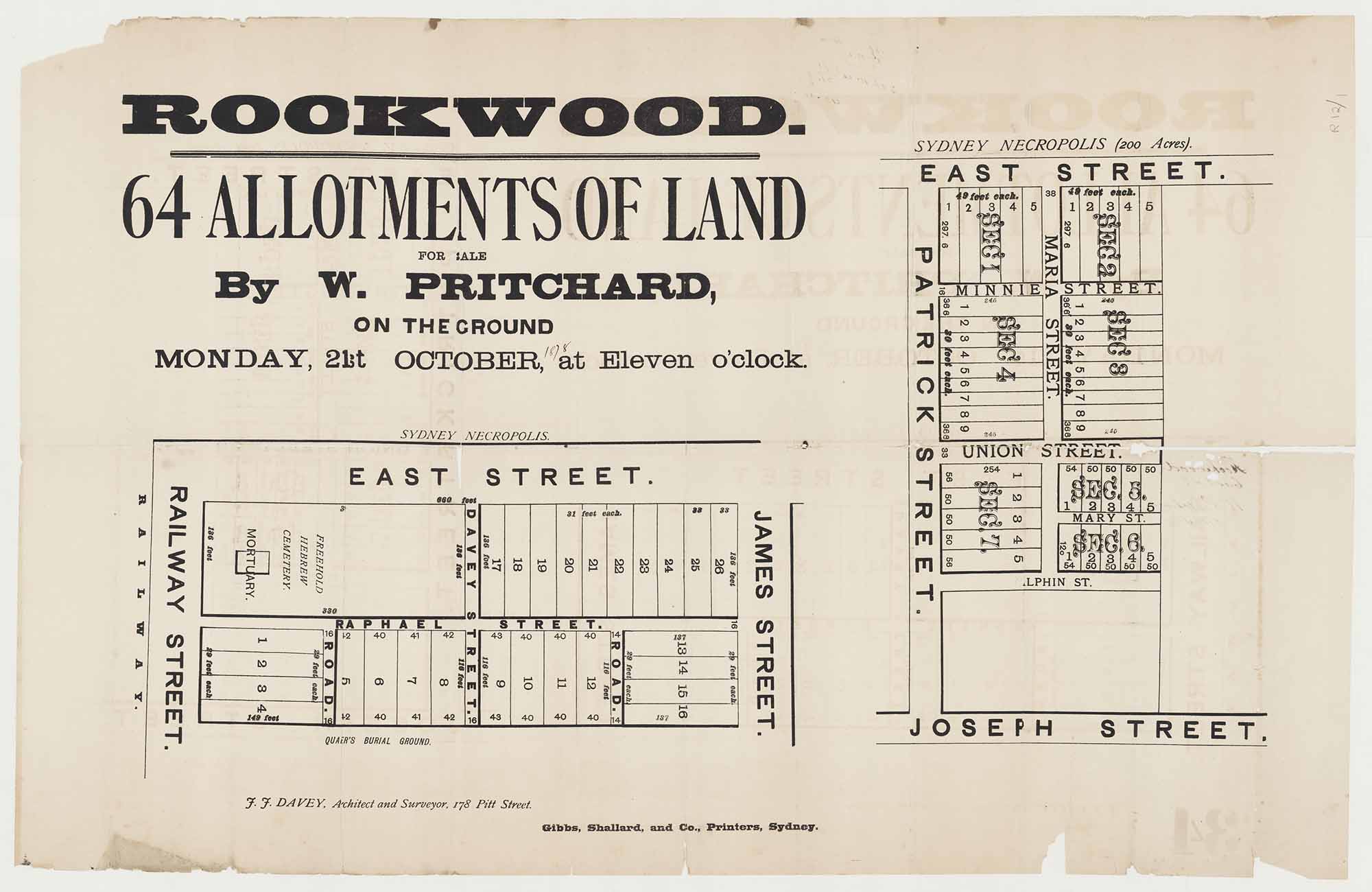

After Therry's death on 6 May 1867, JV Gorman auctioned the land as the township of St Joseph, laid out on a different arrangement. [10] The acquisition of a large area of nearby land for a cemetery by the government meant that home sites in St Joseph had a ready market. The township of St Joseph forms the core of present day Lidcombe. A number of stonemasons bought allotments adjoining the cemetery and established their yards there. [11] Stonemasons' yards still dominate this part of Lidcombe.

The railway comes

The railway to Parramatta Junction (now Granville) opened in 1855. A station opened at Haslams Creek in October 1859, after Therry agreed to pay £350 to help the railway meet costs, and guaranteed traffic to the value of £200 over three years. [12] In August 1862, a road from Parramatta Road to the station was opened, which later became John Street. Another road running south to Bankstown was opened at the same time. It became Joseph Street. [13] In 1866, Bailliere's gazetteer listed Haslems (Haslams) Creek simply as 'the name of a railway station'. [14]

A cemetery would have been appropriate at Haslams Creek on 10 July 1858, when the first railway accident in Australia occurred, killing two passengers and injuring a number of others. Most of the passengers were travelling from Parramatta to Sydney to conduct business or go shopping.

Planning and services

To cater for the needs of residents of the burgeoning town of Haslams Creek, necessary services – including utilities – were provided. A public meeting at Phillip Keifer's Inn at the eleventh milestone on Parramatta Road in 1859 called for the establishment of a post office at the Haslams Creek railway platform, [15] and a post office was opened at Haslams Creek in 1868. [16] The post office at Rookwood operated from the Town Hall in Church Street for some years, until it moved to Joseph Street.

From the 1860s to the 1880s, a number of major roads were officially aligned and gazetted through the area. This enabled better access through the district. These roads included Bachell Avenue in 1864; Kerrs Road about 1874; and Water Street in 1880–81. [17] A road from Granville to Rookwood was surveyed in 1887: it is now Chiswick Road and Water Street. [18]

Sydney's slaughterhouse

The soils in the area were mainly too poor for agriculture. Wianamatta shales, which underlay the area, were the source of the soils, but they quickly lost their fertility, while the watercourses were often salty for long distances away from the Parramatta River. Agriculture did not thrive. On the other hand, livestock could often survive on salt water.

Several large-scale squatters such as James Edrop purchased land in Liberty Plains, which they used to rest cattle driven from the interior. Edrop was also a substantial shareholder in the Sydney Meat Preserving Works, which opened nearby in the 1870s, on the site of Samuel Haslem's and James Wright's grants.

[media]The slaughter and disassembling of livestock into their component parts – meat, skins, hooves, bones, horns, fat, blood and fleeces – was one of the earliest significant industries in the district. The establishment of the Sydney Meat Preserving Company, where Haslams Creek met Parramatta Road, opened the district up for such industries. The company was established in 1869 to process surplus stock for graziers. The works were situated in one corner of a 400-acre (162-hectare) site, most of which was used for stockyards. Activities on the site included slaughtering, butchering, preserving, trimming and boiling down. Advanced canning technology was used under the supervision of the manager, Alban Gee. Gee was manager of the SMP works from 1872 until his death in 1917, becoming a notable local citizen in both Auburn and Lidcombe. The company sold its by-products in both Australia and Asia, and they won numerous prizes. Its successful application of advanced technology made it a leader in food processing in Australia. [19] Most of the shareholders were pastoralists seeking a stable market price for their stock, rather than speculators. [20]

Other livestock industries were soon attracted to the area. George William Cornwell was in business as a butcher at Rookwood in 1880. [21] In May 1877, part of the Francisville Estate at the corner of Francis Street and Parramatta Road was conveyed to a tanner from South Creek, John Garthwaite, [22] who established a tannery there. Other industries associated with animal by-products were Wright's glue works and Bennett's boot factory, both near the Sydney Meat Preserving works in 1890. [23]

Rookwood cemetery

[media]By the mid-nineteenth century, Sydney needed a new cemetery, one that would be accessible by rail, where drainage did not affect nearby residences, and where soil was suitable for the digging of graves. After examining a number of sites for a new cemetery, the government accepted the offer by Cohen and Benjamin of a large area of land at Rookwood, which was formally conveyed to them on 15 August 1862.

[media]To cater for travel to the new cemetery, a branch line running off the western railway was constructed, with an extension to a receiving house being completed on 26 May 1897. The last funeral train service ran on 3 April 1948. [24]

A cemetery needed gravediggers, stonemasons and people involved in the funeral business, so it simulated the development of the new township at Haslams Creek.

[media]And although Rookwood was developing as a village in the late 1870s, there were still few stores. The Post Office Directory for 1878 listed Alfred Abbott as dealer at Rookwood, along with Simeon Gazzard's refreshment rooms, Ann Godfrey's store, and Bernard Gormley's and Henry Moore's pubs. [25] In March 1879, the first retail butcher, a man named Onus, started trading, and Cornwell started his butchery later in the year. [26] Bernard Gormley, a cattle dealer at Rookwood, commenced business as a storekeeper about 1881. [27] He also built the Railway Hotel at Rookwood, first licensed in 1876. [28] By 1890, its license was held by Joseph Abrahams. The Royal Oak was built by S Gazzard about 1878 and was licensed that year. [29]

Although the main groups attracted to settle in the railway township were workers, others not tied so closely to their place of employment also built homes there. Among such new residents was Frederick Lidbury, who moved to Rookwood about 1893 and built a large Gothic two-storey stone mansion opposite the cemetery. He had been manager of the decorating department of James Sandy from about 1882. He became active in local government and was Mayor of Rookwood on a number of occasions. [30]

Lidcombe emerges

In later years, when the name Rookwood no longer appealed to residents, a new name was created for the suburb from Lidbury's surname and that of his main Mayoral opponent, Alexander Larcombe, to create the name 'Lidcombe'. Indeed, the area now known as Lidcombe was known by variety of names over the years. Situated within what was originally the District of Parramatta, it became part of the parish of Liberty Plains, a name that was occasionally used in early years as a locality name. More frequently, it was referred to as Haslams Creek. Therry's proposed township of St Joseph gave it another name by which it was also known for many years. The establishment of Rookwood Cemetery gave it the name by which it was last known before the name was finally altered to Lidcombe.

State Abattoirs

Further development came in the twentieth century, when the establishment of the State Abattoirs enhanced the local focus on livestock processing. The state government officially resumed a site for the abattoirs in March 1907, and work commenced in 1910. [31] The State Abattoirs opened in 1916 with slaughter halls for mutton, pork, veal and beef, and by the 1930s was claimed to be the largest slaughtering unit in the world, although it is unlikely to have exceeded the immense packing yards of Chicago. The works were surrounded by 1500 acres (607 hectares) of stockyards, with most stock coming from Flemington sale yards nearby. The abattoirs finally closed in June 1988. [32]

Like many other industries, the meat processors left their mark on more than just their sites. Meat workers lived in nearby streets. When Arthur Rickard and Company offered the Marne Park Estate in North Lidcombe for sale in 1915, the presence of the abattoirs nearby – with its prospect of ready employment – was a selling point. The number of livestock processing works in the area, along with the abattoirs, meant that many residents were closely linked to the pastoral industry. Many drovers, slaughter men and butchers lived near Parramatta Rd

Other industries developed in the area, and brick and pottery making was prominent around Lidcombe and Berala. Works included Thomas, Henry and John Leigh on Brixton Road, George Acott on Kerrs Road, and James Sims on Brixton Road. [33]

Development and incorporation

With available land, railway access, and jobs at the cemetery or in meat processing or at engineering works nearby, Lidcombe boomed. In 1881, the population was counted as 247 persons. In 1891, there were 2,084 persons, with 4,496 in 1901. [34] In 1911, there were 5,418 persons in Lidcombe municipality. [35] Buildings increased from 424 in 1891 to 502 in 1901 and then reached 772 in 1911. [36]

Initially, the district was unincorporated, so that the New South Wales government provided all services and facilities, such as roads – although it mostly meant that no provision was made at all. A movement to incorporate Rookwood commenced in 1883, but did not achieve success until 10 December 1891, when the municipality of Rookwood was incorporated. After the election of aldermen, the first council meeting was held in Gormley's Hall on 24 February 1892. [37]

Lidcombe Town Hall was built in 1896–7. The foundation stone was laid on 28 November 1896 by Mrs F Lidbury, Mayoress, next to the Fire Station in Church Street. The Town Hall was designed by JB Alderson and built by WP Noller of Parramatta. [38] It was later demolished to be replaced by a block of flats.

Amusements

Bicycling was a popular craze in the early twentieth century. Sturdy and practical, the bicycle provided cheap and easy transport for the workers of the district until their gradual replacement, from the 1950s onwards, by motor cars. To cater for the bicycling craze and the popularity of racing, councils provided bicycle tracks in parks, while road races were keenly followed. Rookwood Bicycling Club competed in a six-mile (9.7-kilometre) road race at Bankstown in March 1908. [39] Local lads who raced successfully were the idols of young boys. Bicycles were often manufactured locally. The Edworthy Cycle was manufactured at 60 Joseph Street, Lidcombe in the 1930s. [40]

The replacement of horse drawn transport, which the augmentation of railway travel started, was a process which had a marked impact. Then bicycles in turn were completely overwhelmed by the motor car.

Brass bands were popular in the district in the early twentieth century, and were part of a much wider popular movement stretching from Great Britain across Australia. They were not a part of the established music tradition, which focussed upon light operetta and parlour pianos, and was much more genteel. They were the major means by which people experienced music for many years.

Water and power

According to Water Board figures, [41] in 1911 a total of 97 new buildings were erected at Rookwood. From 1913 to 1914, there were 144 new buildings erected in Lidcombe. [42] In 1917, weatherboard cottages at Lidcombe with three rooms and a kitchen cost from £330, while identical brick cottages could be had from £570 upwards. [43] Cottages let from 11s 6d per week at Lidcombe. Between 1919 and 1929, the assessed annual value of real estate in Lidcombe trebled. [44]

Electrification of the Western railway line from Homebush to Parramatta commenced in 1929, and by July 1929, there were four electric trains on the service to Parramatta. As part of the electric system, the Flemington Car Sidings opened in October 1928. [45]

An electricity supply was extended to private consumers in Lidcombe on 30 August 1915. Power came from the Electric Light Department of the Sydney City Council. [46] On 1 January 1921, Lidcombe Council was able to inaugurate an extension of electric street lighting to all of the municipality with current supplied by Sydney City Council, so that could commence eliminating gas lamps. [47]

Lidcombe and defence

The area also served as a locus for defence training. In the 1890s, a number of annual military camps for the volunteer military forces were held at Rookwood. [48] As a consequence, a map was produced in 1899, showing the area between Parramatta and Georges River with buildings, vegetation details and topography. [49] The establishment of the naval munitions depot at Newington was another aspect of the involvement of the district in national defence. The magazine was officially acquired by the Commonwealth Government in 1906. [50]

Another aspect of the area's association with wars was that, as the Great War of 1914–18 drew to a close, it was clear that there would be considerable demand for houses across Australia, particularly in urban areas. The War Service Homes Commission aimed to build houses and to finance home ownership for returned diggers and other war workers. The War Service Homes Commission provided single cottages or small groups of cottages in Lidcombe. In November 1919, it bought a series of allotments in the Marne Park Estate to build cottages in group schemes. [51] A 'Soldiers' Settlement' was established at Marne Park in the period 1920–22, with almost 100 houses being built by the Commission. The distinctive cottages erected by the Commission dot the Jellicoe, Mons, Gallipoli and Ostend streets as a result, but they are gradually disappearing, due to current ignorance of their significance.

Rapid growth in Granville, Auburn and Rookwood in the early twentieth century created an urgent need for sewerage, best built as a single scheme. [52] Works to provide a sewerage system started in Auburn in 1926, and further works including Lidcombe commenced the following year. Work continued in the 1930s, with unemployment relief funds being used to employ labour. [53]

Leisure and sport

The Arcadia cinema in Lidcombe originally operated from a site in Joseph Street, in a corrugated iron building, which was partially built on an earthen floor with the roof open to the sky. [54] The Arcadia cinema in Bridge Street was built in 1924, as a multi-purpose building for film screening, dancing or boxing, with L Thompson as lessee. Opposite the Arcadia, the Black Cat Wintergarden supplied refreshments. The Arcadia closed on 1 May 1963, [55] and then operated as a supermarket in the 1980s and early 1990s, until a fire damaged fittings and stock. It was then converted to the Westella Reception Centre.

Clubs, often associated with particular groups, met the needs of local residents for leisure. The large boom in clubs in the 1950s – after they were allowed to serve liquor following the 1954 Royal Commission on Liquor Laws in New South Wales – was also reflected in the area. The Lidcombe Catholic Workmen's Club commenced in May 1946 in a former gym and dance hall, under the auspices of Monsignor Francis Lloyd, parish priest. [56]

Childhood amusements were less structured and mostly based upon activities which required no financial outlay. Playing on the open spaces, which was once common, or along the creeks that bisected the area, was the main delight of children. There were few commercial entertainments directed at children. Yet, when any travelling fair arrived, it attracted an audience keen to savour the delights of the slightly risqué and exotic entertainment on offer.

The playing of sport was actively pursued throughout the area. Cricket was long the most popular sport in Central Cumberland, a fact attested by the long existence of the Central Cumberland Cricket Club. The reputed first cricket game in Lidcombe took place on Edmund Keating's land, with the Keating family making up many of the players. Towards the end of the century, in 1898, Lidcombe Council had decided to establish fresh water swimming baths. Money was borrowed from a friendly society, the Independent Order of Oddfellows. The baths were completed by Lewis & Sanders for £420, on a one-acre site near the station acquired from the SMP Company for £1. They opened early in 1899.

Golf also came to the area. Carnarvon Golf Club was formed 1927 and occupied a site at Day and Carnarvon streets, Silverwater. An eighteen-hole course stretching from Silverwater Road, Derby Street and the Parramatta River served as the club's course.

A game whose popularity is less known was baseball. Even in the 1920s and 1930s, it had a strong following in the district. The Marne Park Baseball Team was a notable squad. They were premiers of the Cumberland District in 1931. [57] The Cumberland Baseball Association was based in Lidcombe by 1933, with two main clubs – the Lidcombe and Marne Park clubs. [58]

New industries

A major impact on the area came with the manufacturing boom of the 1920s. Protected by tariff barriers instituted in 1920, this led to the establishment of many high-tech industries. As a result of that protection, the manufacture of electrical goods, motor car manufacturing, the development of a steel construction industry, and expansion of the woollen and knitted industries, were all represented in Lidcombe.

The Ford Motor Company of Canada initially established its assembly plant for New South Wales at Sandown on the river near Parramatta. In 1935, however, they shifted their New South Wales operations to a new plant on Parramatta Road in the Lidcombe Municipality, where a new factory was designed and built facing Parramatta Road

When the state government awarded contracts for equipment to electrify suburban railways in 1924, it made it a condition of the tender that local manufacture be arranged. Associated General Electric Industries Ltd set up a works at Lidcombe to complete their share of the contract. In 1926, the company decided to manufacture the electric tram motors from Australian materials. Within a short time, they had manufactured the largest electrical railway motors so far produced in the world. In 1930, the merger of Metropolitan Vickers Australia, the Associated General Electric Company and Ferguson Pailin amalgamated their manufacturing on the Lidcombe site. Domestic appliance manufacture was commenced in the early 1930s. [59]

Jantzen (Australia) Ltd acquired the Australian rights of the US company Jantzen, and was established with US capital and expertise. A factory was built facing Parramatta Road, between Mons and Ostend streets. Manufacture of swim suits commenced in July 1928. [60] About 1933, to keep its skilled employees in the slack season, the company began to manufacture men's knitwear. [61]

The Great Depression

The Great Depression put many out of work. In 1933, 19 per cent of men in Auburn Municipality were unemployed, while 23 per cent in Lidcombe were out of work. [62] Lidcombe, with its large contingent of waged employees, suffered severely when workers were laid off from industry.

Lidcombe Council accepted the state government's 'work for the dole' scheme earlier than many other councils. The scheme came into operation for Lidcombe in June 1933 and continued until July 1937. Works completed included 14 miles (22.5 kilometres) of roads, four miles (6.4 kilometres) of kerbing and guttering, and three miles (4.8 kilometres) of concrete paving and tarred footpaths. Over £500,000 was spent on storm-water channel construction. [63]

A camp for the unemployed was established near Marne Park in 1931–32. Families evicted from their rented homes were housed there in tents, the cause of numerous complaints. The camp was closed in March 1932.[64]

The Great Depression of the 1930s also caused the establishment of various locally based relief schemes. Although most could not provide the full range of assistance needed to cope with the magnitude of the economic collapse, they represented local initiatives to help. The local benevolent society arranged soup kitchens for children and the local unemployed in 1930. Distribution centres were located at Lidcombe Town Hall, Berala Church of England, and the Catholic schools at Lidcombe and Berala. With the advent of government food relief, they shifted their attention to medical relief, clothing, and drugs. [65]

War industries

In World War II (1939–1945), Lidcombe became a vital link in the network of factories producing military aircraft. Aluminium was produced at Alcan in Granville. Beaufort bombers and Beaufighter fighter planes were assembled at the Chullora railway workshops. Their engines were manufactured at Lidcombe. Australian Forge & Engineering Pty Ltd manufactured forgings of high quality steel. These were then further machined and incorporated into Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines, manufactured by the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation factory in Birnie Avenue, Lidcombe. [66] By late in the war, the Lidcombe plant was manufacturing the Rolls Royce Merlin engine, which had powered the British Spitfire. In the Australian case, however, these engines were used to power the Australian-produced version of the American P-51 Mustang fighter. [67] The Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation site has been cleared of all its buildings.

Postwar development

The Cumberland County Plan zoned new areas of land for industry in Sydney's then western suburbs. Established plants in the inner city – unable to obtain land nearby for expansion – had to shift to areas zoned for industry in the west. Industry flooded into the district. Lidcombe, for example, attracted Industrial Sales & Service Pty Ltd, the new farm machinery works of International Harvester Company of Australia Pty Ltd, and the auto assembly works of Hastings Deering Pty Ltd, all to sites on Parramatta Road, so that they could be well served by road transport. [68]

In the postwar period, the Housing Commission was active in Auburn and Lidcombe. Although the Commission constructed a number of group developments throughout the municipality, none achieved the scale and impact of the Commission's schemes in South Granville, Villawood, and the Dundas Valley.

Lidcombe's diversity

For many years after 1788, diversity amongst Sydney's population largely focussed upon the divide between Irish and the non-Irish. Lidcombe, with Therry's property and the presence of Edmund Keating, was in some ways an Irish centre, while it is likely that many of the woodcutters hailed originally from Ireland. Later in the nineteenth century, Chinese hawkers were known to visit Rookwood in the 1870s.

A small contingent of non-British settlers lived in the district, but it was only with the post-World War II influx of European – and then, later, Middle Eastern and Asian settlers – that the population mix became much more diverse.

One group which developed a local landmark was the Ukrainian community, who built a church and a community centre in Church Street, Lidcombe. But European settlers were overtaken by Middle Eastern immigrants in the 1960s and 1970s. These congregated in the area, making it one of the major Arabic/Middle Eastern centres in Sydney. At the 1991 census, 47.2 per cent of the population of the municipality was born overseas, a 20 per cent increase from the census of 1986. The largest groups came from Vietnam (14.2 per cent), Lebanon (11.9 per cent) and Turkey (10.8 per cent). Roman Catholics made up 31.3 per cent of the population, with Muslims the next most numerous, with 15.9 per cent. Anglicans were the only other large group, with 13.2 per cent. Those professing no religion made up 10.3 per cent of the population. All other groups totalled 40 per cent or less of the population. [69]

The influence of the car

Also in the postwar era, retail redevelopment at Parramatta, such as the Grace Brothers development, and the opening of a David Jones regional store in November 1961, continued to draw customers to Parramatta from a wide catchment. Within a short space of time, Bankstown Square had been developed and began to draw customers seeking comparison shopping away from Lidcombe. A regular bus service connected Bankstown to Lidcombe along Rookwood Road, and it drew many shoppers to Bankstown Square.

As car ownership became more widespread across the district, residents deserted their small local shopping centres for larger centres such as Bankstown. The development of Westfield at Parramatta from 1975 onwards drew shoppers from far and wide. In consequence, local shopping centres began to haemorrhage slowly. Lidcombe, only ever a modest local shopping centre, was visibly affected.

On the other hand, the decline of the small corner shop has been partly arrested by the diverse ethnic mix of the district. Although the number of such shops has declined overall, many still function, often supplying a niche market, selling goods in demand by people from various cultural backgrounds. Although such stores are also functioning in the main shopping centres, it appears that the lower rate of car ownership for many recently arrived migrants has ensured that the clientele within walking distance is still a viable one for such storekeepers.

However, the staged construction of what eventually became the M4 motorway radically altered transport patterns, initially taking a great deal of pressure off Parramatta Road. Later, privatisation of part of the road (previously constructed with public money in order to tempt investors to complete the missing link from Parramatta all the way to the west) attracted a great deal of public opposition. Again, traffic was deflected to Parramatta Road where it runs through Lidcombe. The section of the M4 between Auburn and Parramatta is the section on which a toll is charged, and vehicles seeking to escape the toll divert to Parramatta Road. [70]

Notes

[1] W Bradley, A Voyage to New South Wales – The Journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786–1792, Sydney, 1969, p 75–6

[2] J Jervis, 'The Road to Parramatta – Some Notes on its History', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, 13, 1927, p 67–9

[3] J Jervis, 'The Road to Parramatta – Some Notes on its History', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, 13, 1927, p 78

[4] 1828 Census, Householder's schedules, State Records New South Wales 4/1238.2

[5] Lidcombe Public School Centenary, 1879–1979, Baulkham Hills, [1979], p 9

[6] Lidcombe gala week, June 10 to 16, 1933: official souvenir and programme, Express Newspaper for the Council of the Municipality of Lidcombe, Lidcombe New South Wales, 1933, p 9

[7] Conveyance of Kirk's land, Land Title Office Deed, No 588 Bk F

[8] See conveyance of land sold to railway, Land Titles Office Deed, No 326 Bk 35; Plan in Lidcombe Subdivision Plans, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

[9] EM O'Brien, Life and Letters of Archpriest John Joseph Therry, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1922, pp 281–2

[10] Mitchell Library Map M2/811.1338/1867/1, State Library of New South Wales

[11] Deposited Plan 397, Land Titles Office Plans Room; Certificate of Title 52 f 115

[12] RG Preston, 125 Years of the Sydney to Parramatta Railway, New South Wales Rail Transport Museum, Burwood, 1983, p 95

[13] SC Wayland, Lidcombe and its Development as an Industrial Centre, Lidcombe, 1941, p 11

[14] Bailliere's New South Wales gazetteer and road guide, compiled by RP Whitworth, FF Bailliere, Sydney, 1866, p 259

[15] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 September 1859, p 5

[16] Australia Post, 'Auburn West Post Office History', typescript, 1988, p 1

[17] Plans R.388.1603; R.1148.1603; R.1451.1603; R.1909.1603, Lands Dept Plans Room

[18] Auburn Jubilee, Auburn 50 years, p 14

[19] KTH Farrer, A Settlement Amply Supplied – Food Technology in Nineteenth Century Australia, Melbourne University Press, Carlton Victoria, 1980, pp 88, 118–20

[20] Australian Town and Country Journal, 22 Nov 1873, p 656

[21] Bank of New South Wales, Parramatta Signature Book

[22] Land Titles Office Deed, No 457 Bk 169

[23] 'The Suburbs of Sydney No XXXIV, The Unincorporated Suburbs comprising Rookwood, Auburn, Bankstown etc', Echo, 11 Dec 1890

[24] New South Wales Public Transport Commission, 'Historical Notes on Rookwood Cemetery, Lidcombe to Cabramatta and Clyde to Carlingford Lines', pp 5–6

[25] J Tingle, Post Office Directory, February 1878, p 493

[26] SC Wayland, Lidcombe and its Development as an Industrial Centre, Lidcombe, 1941, pp 11–2

[27] Minutes of Evidence, B Gormley, 9 June 1896, in Bankruptcy File No 10916, State Records New South Wales 10/23099

[28] New South Wales Government Gazette, 13 Sept 1876

[29] 'The Suburbs of Sydney No XXXIV, The Unincorporated Suburbs comprising Rookwood, Auburn, Bankstown etc', Echo, 11 Dec 1890; New South Wales Government Gazette, 27 August 1877

[30] Cumberland Argus, Xmas Number, 19 Dec 1907, p 25

[31] Fox & Associates, 'Homebush Bay Conservation Study', Sydney, 1986, p 125

[32] Review Pictorial, 8 June 1988, p 1

[33] W Gemmell, And So We Graft from Six to Six – The Brickmakers of New South Wales, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1986, p 63

[34] Census, 1901, p 547

[35] Census, 1911, p 2033

[36] Census, 1891, p 538; 1901, p 498; 1911, p 2033

[37] SC Wayland, Lidcombe and its Development as an Industrial Centre, Lidcombe, 1941, p 15

[38] Lidcombe gala week, June 10 to 16, 1933: official souvenir and programme, Express Newspaper for the Council of the Municipality of Lidcombe, Lidcombe New South Wales, 1933, p 11, 13

[39] Cumberland Argus, 21 March 1908 p 2

[40] Lidcombe gala week, June 10 to 16, 1933: official souvenir and programme, Express Newspaper for the Council of the Municipality of Lidcombe, Lidcombe New South Wales, 1933, p 29

[41] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 Jan 1912

[42] Building, 12 Dec 1914, pp 76–7

[43] MA Harris, Where to Live, p 127

[44] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 Jan 1930

[45] RG Preston, 125 Years of the Sydney to Parramatta Railway, New South Wales Rail Transport Museum, Burwood, 1983, pp 91, 111

[46] 'Electricity', Vertical File, Auburn Library Local Studies Collection

[47] Lidcombe Municipal Council, Triennial Report, 1920–1922, Parramatta, 1922, p 11

[48] See, for example, Australian Town and Country Journal, 16 April 1898, pp 25, 31

[49] Department of Lands, Map of the Country Between Parramatta & Georges Rivers, 1899

[50] PR Stephensen, The History and Description of Sydney Harbour, p 290

[51] Certificate of Title 2331 f 28; Certificate of Title 3120 f 242

[52] 'Report on Proposed Sewerage Scheme for Granville, Auburn and Rookwood', New South Wales Parliamentary Papers, 1916, VI, p 681

[53] Liberty Plains, p 171–2

[54] SC Wayland, Lidcombe and its Development as an Industrial Centre, Lidcombe, 1941, p 59

[55] Liberty Plains: a history of Auburn New South Wales, centenary edition, Council of the municipality of Auburn, Auburn, New South Wales, 1992, p 288

[56] Review Pictorial, Centenary issue, 16 Sept 1992, p 14

[57] Cumberland Argus, 21 July 1932

[58] Lidcombe gala week, June 10 to 16, 1933: official souvenir and programme, Express Newspaper for the Council of the Municipality of Lidcombe, Lidcombe New South Wales, 1933, p 5; See also T Stafford, Living In Liddy, the author, Ettalong Beach New South Wales, 1991, p 141

[59] Lidcombe gala week, June 10 to 16, 1933: official souvenir and programme, Express Newspaper for the Council of the Municipality of Lidcombe, Lidcombe New South Wales, 1933, pp 37–9

[60] Lidcombe gala week, June 10 to 16, 1933: official souvenir and programme, Express Newspaper for the Council of the Municipality of Lidcombe, Lidcombe New South Wales, 1933, p 42

[61] SC Wayland, Lidcombe and its Development as an Industrial Centre, Lidcombe, 1941, p 37

[62] 1933 Census, pp 126–7

[63] SC Wayland, Lidcombe and its Development as an Industrial Centre, Lidcombe, 1941, p 77

[64] Liberty Plains: a history of Auburn New South Wales, centenary edition, Council of the municipality of Auburn, Auburn, New South Wales, 1992, p 303

[65] Lidcombe gala week, June 10 to 16, 1933: official souvenir and programme, Express Newspaper for the Council of the Municipality of Lidcombe, Lidcombe New South Wales, 1933, p 47

[66] DP Mellor, The Role of Science and Industry, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1958, pp 384, 391

[67] AT Ross, Armed and Ready: The Industrial Development and Defence of Australia 1900–1945, Armstrong and Turton, Sydney, 1995, pp 321–4; 344

[68] Architecture, Jan–Mar 1953, p 1; July–Sept 1953, p 64; July 1950, p 94

[69] Ethnic Affairs Commission of New South Wales, The People of New South Wales – Statistics from the 1991 Census, Sydney, 1994, p 43–4

[70] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1994, p 5

.