The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Surry Hills

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Surry Hills

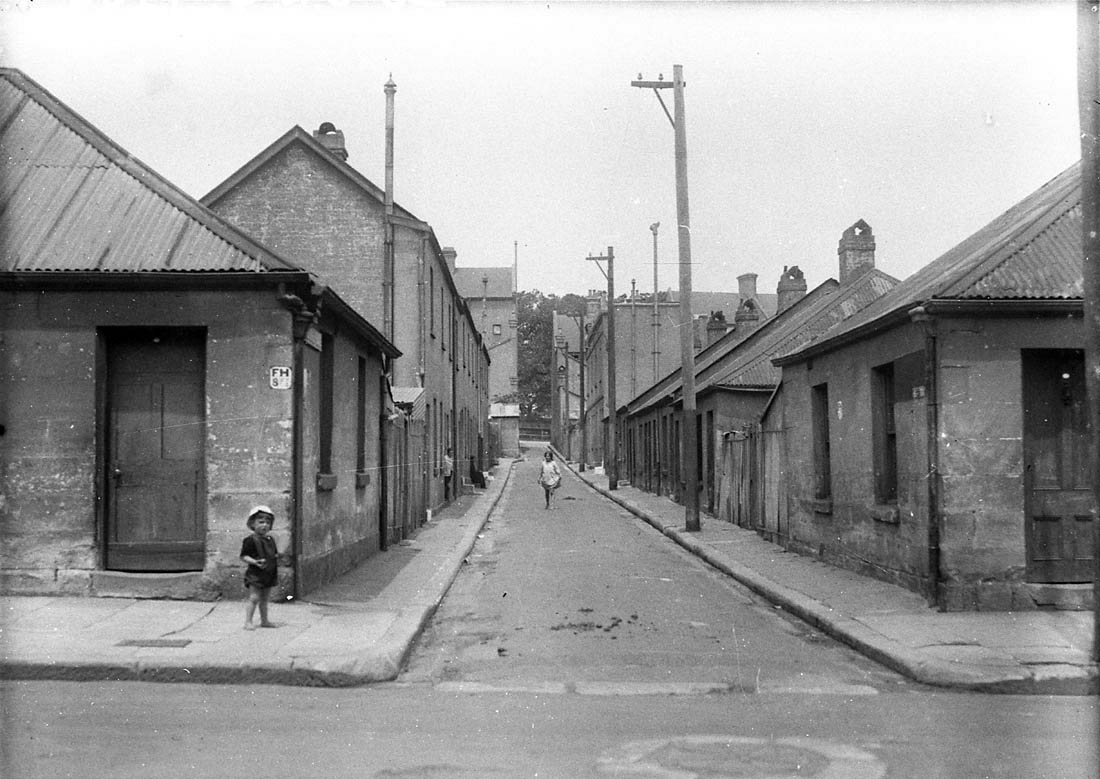

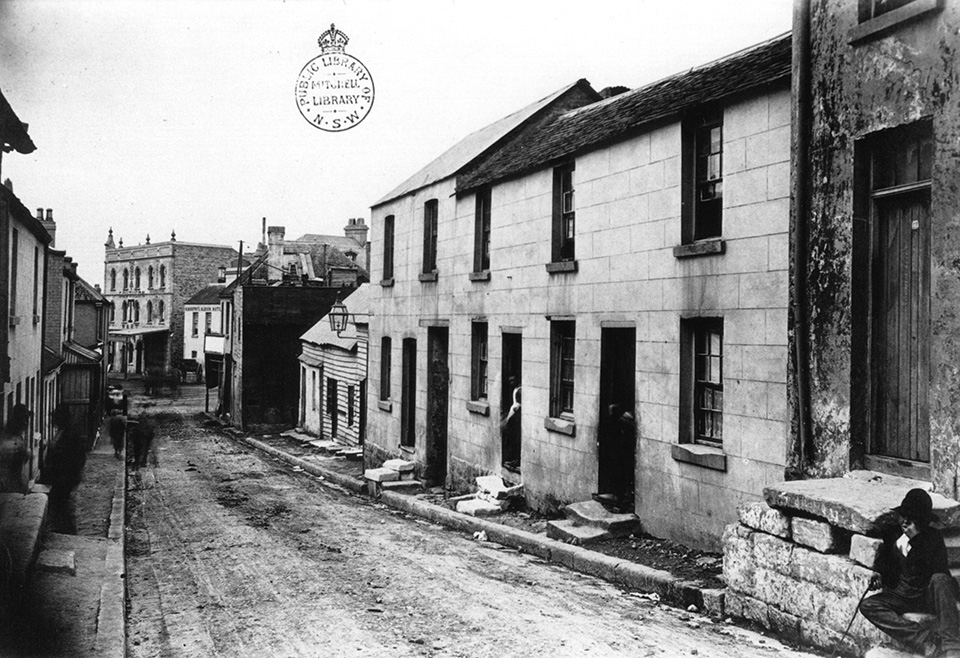

[media]Surry Hills is one of those Sydney suburbs that has seen its stocks go up and down: it has been praised for its 'healthy breezes and beautiful views', but at other times damned as a squalid slum breeding crime and immorality. It has been home to colonial bluebloods in opulent villas and townhouses, but it has also sheltered the poor in dark basements and attics of appalling meanness. And for the Cadigal people, the original inhabitants of the land, the coming of the white men was an unmitigated disaster.

Sandy and full of swamps

One of the earliest references to the area that is now Surry Hills expresses the disappointment of the new arrivals with it:

Between Sydney Cove and Botany Bay the first space is occupied by a wood, in some parts a mile and a half, in others three miles across; beyond that, is a kind of heath, poor, sandy, and full of swamps … [1]

[media]Governor Phillip's main concern was feeding his flock, and Surry Hills seemed to hold out little hope in this regard: on the north, the area was bounded by a sandstone traverse ridge rising in the east to a higher ridge where the military barracks would eventually be built. In the south was an enormous sandhill (between where Devonshire and Cleveland Streets are now), referred to as Strawberry Hill. Between these two boundaries was a plateau of sandstone running north-south along the line of the present Crown Street. It was overlaid by a shale cap which weathered into hard blue clay. While this clay was eventually much sought after for brickmaking, it was useless for crop-growing, and caused innumerable problems for later residents:

When dry and hard it did not absorb water easily…Conversely, once the clay had absorbed water, it became a sticky mass… [2]

As well, drifting sand often covered much of the area, while at the foot of the escarpment and among the sandhills, swampy and poorly drained hollows formed.

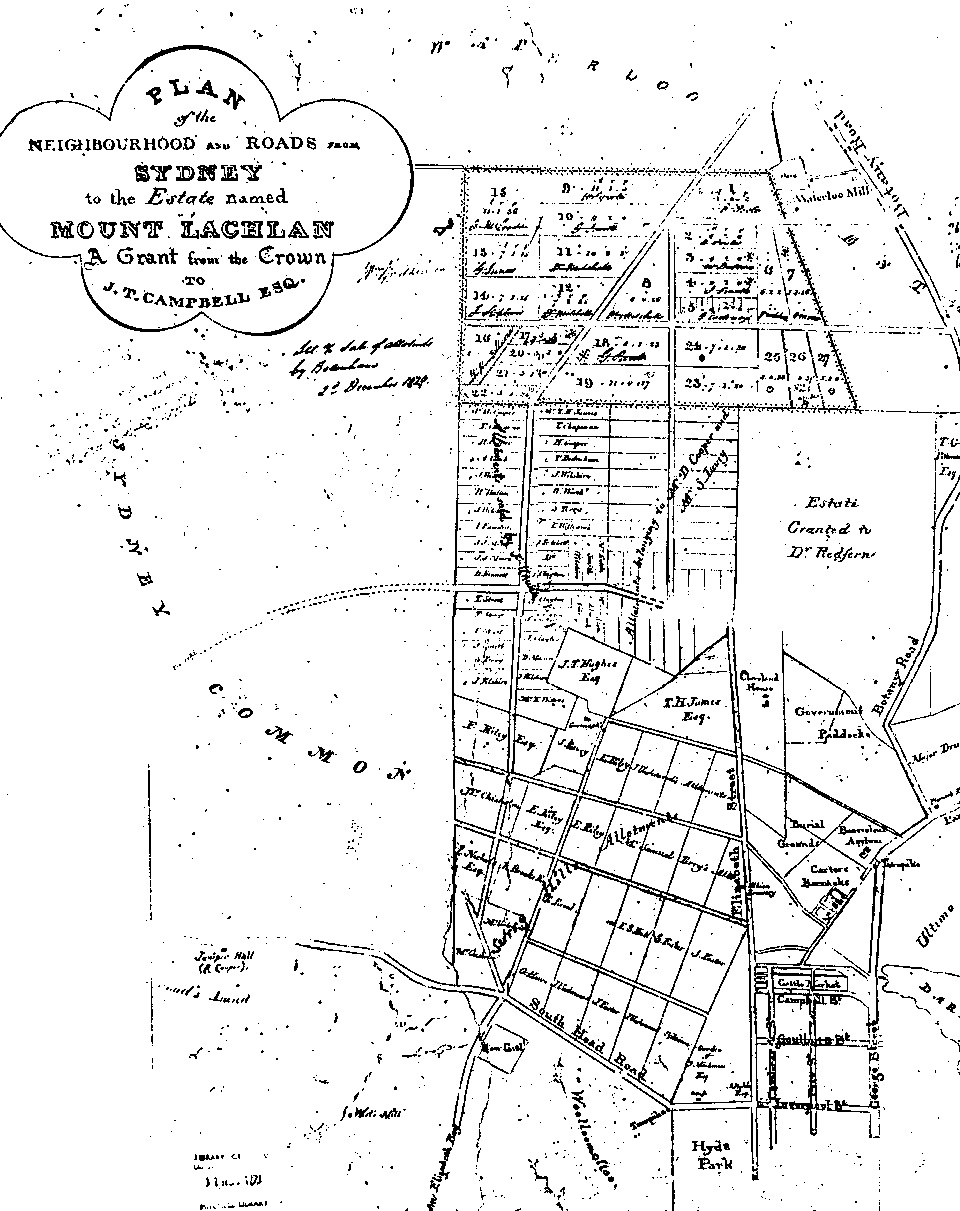

Despite the unpropitious nature of the area, land grants in the 1790s saw much of Surry Hills come under private ownership, and the desperate food needs of the colony saw the development of grazing in the area. In October 1793 Captain Joseph Foveaux was granted 85 acres (34 hectares) of land to the east of the town boundary. A few weeks later the grant was increased to 105 acres (42.5 hectares): Foveaux's grandly named 'Surrey Hills Farm' took in most of what is now Surry Hills, and over the next few years he was given additional acreage, so that by the time he sailed for Norfolk Island in 1800, he had become one of the largest sheep and cattle owners in the colony.

[media]To the east of Surrey Hills Farm was George Farm, a 70-acre (28-hectare) grant to John Palmer, who had come with the First Fleet as purser on the Sirius. Between Foveaux's farm and the South Head Road (built along that traverse ridge), a 25-acre (10-hectare) block had been granted in 1795 to Alexander Donaldson, and this was acquired by Palmer soon after. 'Little Jack' Palmer, who had been appointed Commissary General in June 1791, was one of the most enterprising of the early settlers and much involved in private speculations. But by backing the wrong party in the Rum Rebellion – he supported Governor Bligh – he lost his official positions and remunerations, and experienced grave financial difficulties, so that his Surry Hills estate was sold in 1814 to settle his debts.

Surry Hills streets

The sale of Palmer's large estate to a large number of private owners – in lots of anything from 5 to 13 acres (2 to 5 hectares) – contributed to the shambolic development of the suburb. Roads were indiscriminately laid down, many of them in contradiction to the grid pattern already laid out by Surveyor-General James Meehan, who had mapped out a grid pattern of roads for the suburb in that same year. As one historian has noted,

the survival of some of his streets, the loss of others and the laying of other road networks on top of Meehan's original plan, all contributed to the later jumble of Surry Hills' streets.[3]

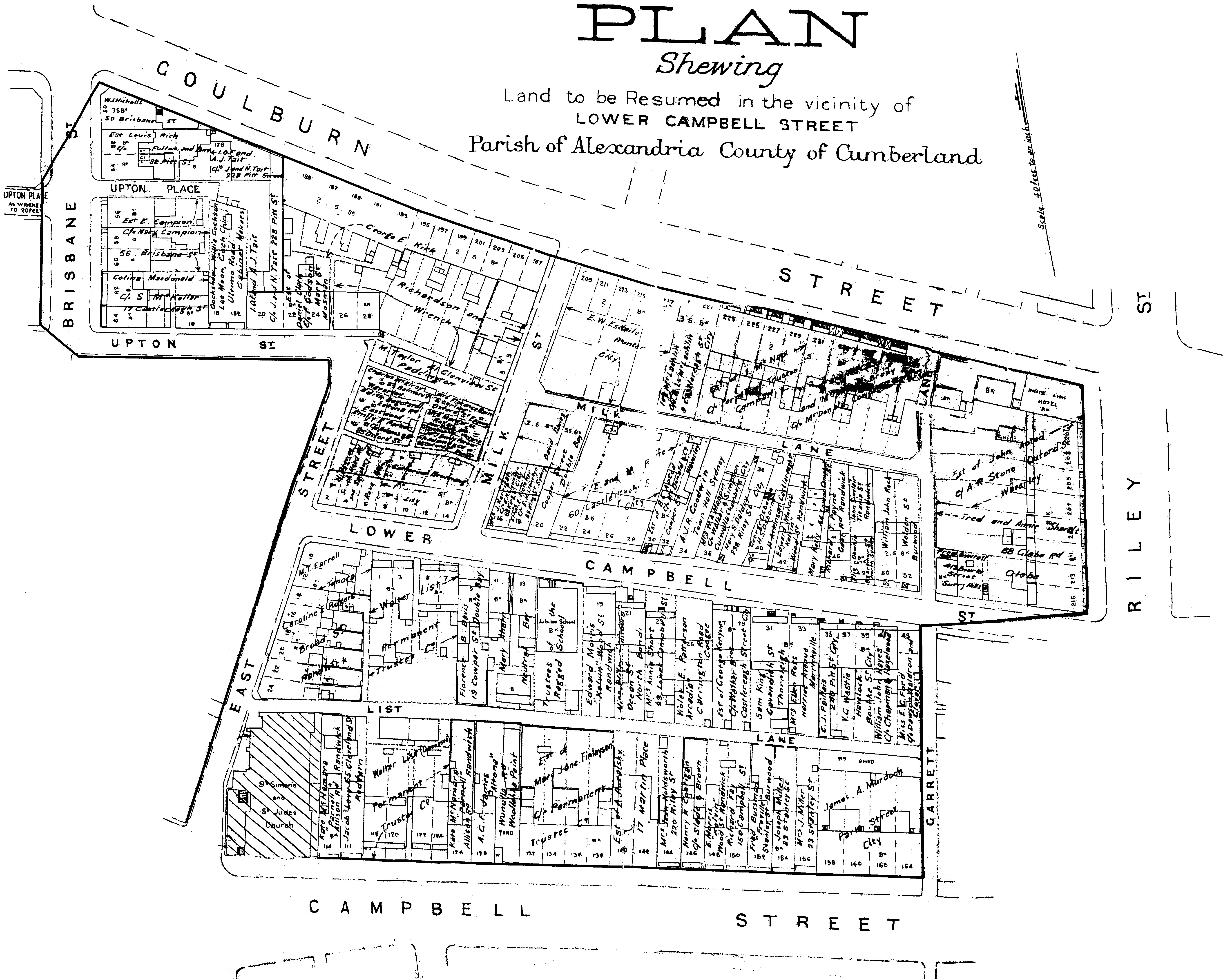

[media]In an attempt to impose some order, in 1834 Surveyor General Thomas Mitchell drew up a new road plan which he had proclaimed, but his street layout cut across the properties of many local landowners, and from the 1830s the colonial government was besieged by claims for compensation, with decades of wrangling between landowners, the government and the new Sydney Municipal Council over the legal status of streets and the numerous encroachments upon them. Even in the early 1880s, it took the council 20 years to negotiate for the widening of Campbell Street between Elizabeth and Foster streets, and as late as 1894 the City Surveyor was still blaming the 'errors' of 1834 for the different direction, width and levels of many of the area's streets.

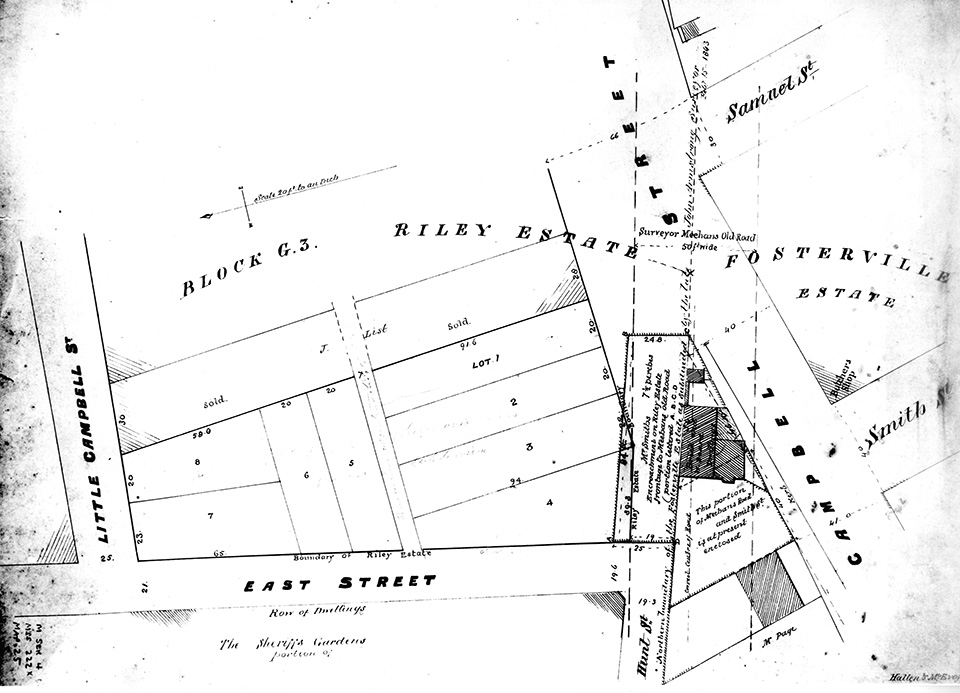

[media]Adding to the debacle was the disposal of the Riley Estate. When Edward Riley, who had bought up many allotments in the Surry Hills area, committed suicide in 1825, he left two conflicting wills, leading to years of litigation among his heirs. This led to the government appointing a commission to oversee the eventual division of Riley's lands into seven parcels of equal value – which were raffled amongst the seven heirs. Roads laid down to separate the seven parcels did not align with those laid down by Meehan in 1814, and so the east-west streets of Surry Hills have 'inexplicable bends' in them: these simply mark the point where the streets of the Riley Estate meet those established by Meehan decades earlier.

Gardens and industry

When Palmer's land had been cut up for sale in 1814, the buyers were urged to develop their acreages as market gardens to feed the colony's growing population. Besides these market gardens there were early industries. Stone quarrying was underway on various sites, and by 1824 the activities of woodcutters, turfcutters, quarries and grazing stock had caused 'serious injury' to the local landscape. The local clay led to brick kilns being established in the area.

But the Surry Hills area, by the late 1820s still 'in the bush' on Sydney Town's southern outskirts, had attracted some of the colonial gentry. The earliest resident of Surry Hills was the banker, grazier and proprietor of The Monitor, Edward Smith Hall, who settled there in 1814. There was also Charles Smith, whose grant was named Cleaveland Gardens, while in the early 1820s the wealthy ex-convict and merchant Daniel Cooper settled on 19 acres (7.6 hectares) bought from Charles [media]Smith: Cooper built Cleveland House, from which Cleveland Street drew its name. And in 1824 the well-connected solicitor George Wigram Allen sold his 'country estate' in Surry Hills and moved back into a cottage in Elizabeth Street, because Surry Hills was 'too far from town'. [4]

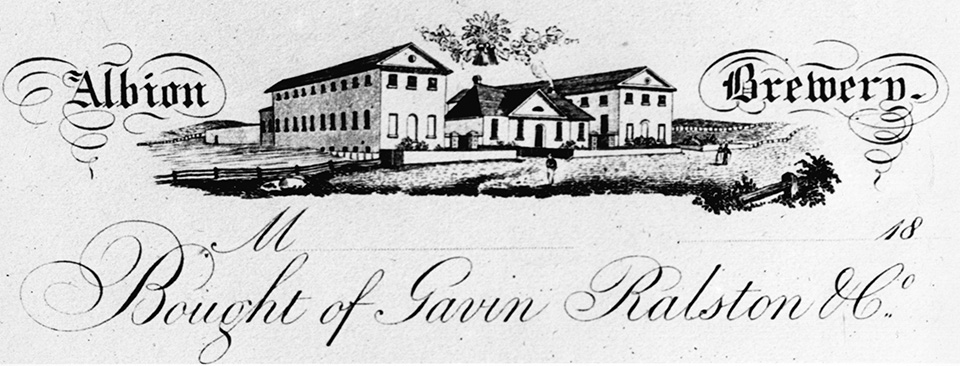

Another convict who made his mark on Surry Hills was 'the Botany Bay Rothschild' Samuel Terry.[media] He was also one of the original purchasers at the 1814 sale, and in 1826 he laid the foundation stone of his Albion Brewery, which initially used a stream of fresh water that trickled down through the sand of nearby Strawberry Hill. Known later for its unique flavour, his beer was made with water drawn from the creeks which drained from the nearby Devonshire burial ground.[media] Other prominent early residents were John Terry Hughes, who married Samuel Terry's stepdaughter Esther, and resided in Albion House; and Lancelot Iredale, whose home was Auburn Cottage, designed by John Verge.

From village to suburb

By the early 1830s, a village began to take shape, and this process was accelerated by the economic boom of the 1830s, which saw mercantile profits increasingly turned to investment in land. [media]Subdivisions began to occur, as with the Strawberry Hill Estate in 1832. And because of its proximity to the spreading Sydney Town, the once-neglected sand and swamp of Surry Hills became more desirable as a residential area. [media]The growing number of subdivisions would lead, by the 1860s, to an advancing tide of the terrace houses that would come to dominate the Surry Hills skyline.

In 1849, the whole of Surry Hills and Woolloomooloo combined could boast only 800 houses, but within 10 years, the housing stock of Surry Hills alone had grown to 1,900, and by the 1890s the district had reached its zenith as a residential area. By then, the tangled network of streets was crammed with nearly 5,300 dwellings in the long rows of brick double-storey terraces that came to characterise Surry Hills in its prime. [media]Indeed, the 40 years between the gold rushes of the early 1850s and the depression of the early 1890s saw the making of Surry Hills as a residential district, with the surges in house-building activity coinciding with periods of economic boom.

Four short decades transformed Surry Hills from a scattered collection of villages, interspersed by scrubby paddocks and the occasional mansion, linked by unformed streets that were not much more than glorified sand tracks, into one of the city's most populous districts. In 1891, Cook Ward, which covered Surry Hills and Moore Park, housed more people than Balmain – then the largest suburb of the metropolis – and accounted for nearly 28 per cent of the population of the Sydney municipal area. But as population increased and houses became more closely packed, there was a corresponding deterioration in the level of amenity and quality of life for the suburb's residents.

With inadequate powers granted to it by the colonial legislature, the Sydney Municipal Council was unable to force landlords and speculative builders to connect even new houses to the water supplies, and the provision of formed roads through the area, and of sewerage and drainage, was exasperatingly slow, largely because of the shortage of funds. [media]Even the completion of the Crown Street Reservoir in 1859, while it brought some relief, could not stop the apparent 'decline' of the suburb, so that by the turn of the century it had blossomed into the archetypal slum of Edwardian Sydney. This situation was exacerbated by the 1890s depression, which badly affected the local economy, ensuring that pawnshops had a growing business.

In the 1850s the social mix of the district was still fairly evenly spread, but the 1860s and 1870s saw subtle changes, as a growing number of mechanics, skilled artisans and shopkeepers came to dominate local life, displacing the declining gentry. At the counters of the corner shops, in the offices of the small factories and workshops, from the front pews of the Sunday morning congregations, and especially on their weekly rounds as rent-collecting landlords, their positions in the social and economic hierarchy of the close-knit community were confirmed. In 1871, 46 per cent of all Surry Hills landlords also lived within the suburb.

Despite the rapidity of development over these decades, parts of Surry Hills still retained their village atmosphere, and the local economy was quite varied. [media]There was, of course, a strong building trade, using locally produced materials to build the suburb's housing; market gardening remained scattered throughout the area; there were coach-building works employing blacksmiths, bodymakers, coach painters and upholsterers, as well as saddlers and harness makers. Tanning and currying were also prominent in the area, with many firms appearing after legislation evicted them from the city proper. Their foul odour and noxious effluent flowed through the area for decades.

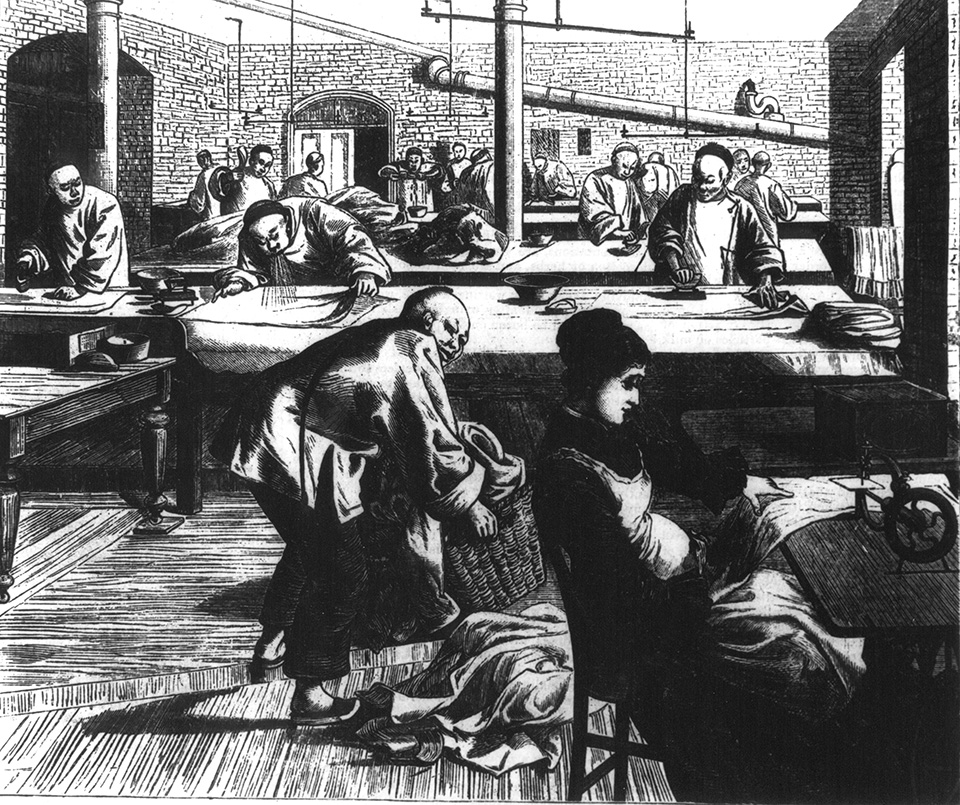

[media]The clothing or rag trade was also prominent in Surry Hills, usually through outwork or piecework systems, and in the houses off the narrow lanes of Surry Hills women ran up slop garments for Dawson's of Brickfield Hill or Cohen Brothers of Goulburn Street, in an effort to supplement often inadequate family incomes.

Schooling Surry Hills

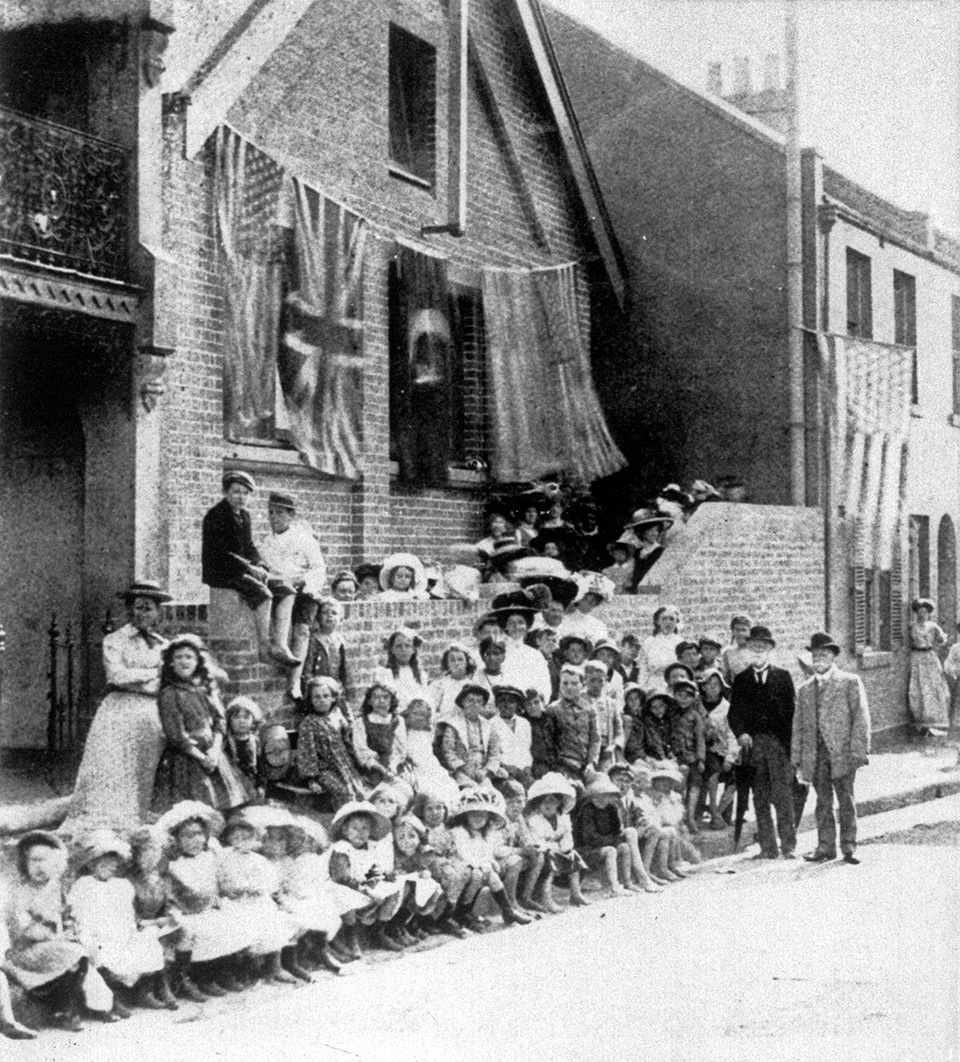

[media]Social infrastructure had begun to be put in place. To meet the educational needs of the area, several small church schools were opened: these, after 1848, were funded by the colonial government. In 1856 the Board of National Education established Cleveland Street Public School in an imported prefabricated iron building lined with boards, canvas and paper, into which were crammed the pupils – nearly 700 by 1867. In 1868 the imposing edifice still standing in 2009 was opened, and by 1878 was educating nearly 1300 students. In that same year, Crown Street Public School opened, and within a year a staggering 1608 students were enrolled. Enrolments there had to be limited until other schools were set up in the area. [media]In 1880 an infants’ school was opened in Brisbane Street; from 1872, a fashionable school for young ladies, the Argyle School, was opened by Miss Emily Baxter at Arthurleigh in Albion Street, also known as Doctor's Row. Devonshire Street Public School began in rented premises in 1874.

By the mid-1870s, these inner-city schools were 'literally crammed with children'. [5] Compulsory education, introduced in 1880, had its effects.

There were also the schools run by the churches. Despite the withdrawal of state aid to church schools in 1890, the Catholics of Surry Hills were served by St Francis's School at Brickfield Hill and by St Peter's on Devonshire Street. The local Wesleyan and Congregational schools continued on, but in reduced circumstances.

Growing into a problem

The growth in the school populations reflected population growth overall. During the 1870s small subdivisions continued to fill the remaining areas of open space, and throughout the length and breadth of the suburb there were now scores of small workshops, largely employing locals. [media]By the end of the 1880s there were blacksmiths' shops, flour mills, foundries, builders' supply yards, coal yards and galvanising works; scattered amongst them were livery stables, ginger beer makers, biscuit factories and steam laundries. And working their way through all this were the dealers and Chinese hawkers, announcing their fresh rabbits, vegetables, fish, milk, and clothes pegs – to which, by the end of the century, were added the click and hum of textile knitting mills and printing works, and the drone of the sewing machine.

By 1891 the area's population was almost 30,000, and by the end of the century the suburb was largely built out, and a testament to the dangers of rapid and uncontrolled urban development. Local and colonial governments apparently possessed neither the legislative power nor the political will to enforce the orderly development of Surry Hills. Indeed, over the late nineteenth century, the power of private property remained unchallenged. Owners and developers enjoyed a remarkable degree of control over the processes of urban growth, land use and public amenity. They essentially had a free hand to build what they liked where they liked, regardless of street alignments, drainage patterns, block size, housing quality or public health. [media]It was profit, not planning, that built late-nineteenth-century Surry Hills, with its overcrowded tenements, poor drainage, and bad health – exacerbated by the plague of 1900. Adding to the suburb’s tensions were the competing demands of residential and industrial land use.

The environment of Surry Hills seemed to cry out to the growing movement for slum eradication that had been emerging in the late nineteenth century. [media]The Anglican Archdeacon FB Boyce had pinpointed Surry Hills as a prime target for remodelling, and in 1905 the Sydney Municipal Council had been granted powers to resume and rebuild whole areas, nominally for 'street widening'. The environmental determinism of the 1909 Royal Commission on the Improvement of Sydney spelt out strategies to 'cleanse' the inner city.

[media]In this context, the emergence of the Labor Party was a beacon of hope 'where there had been none before'. [6] To the residents of Surry Hills, the party machine was merely an extension of existing local networks: it functioned like an extended working-class family and rewarded the party faithful with contacts, support and – most importantly – jobs. While outwardly it could be seen as corrupt, membership provided 'an essential survival skill for those who would otherwise gain nothing'. [7]

Poverty and survival

The early decades of the twentieth century saw Surry Hills at its peak as a residential enclave of Sydney, even as its reputation was at its lowest ebb. Encouraged by the provision of adequate suburban transit systems after 1880, the middle classes were in the process of fleeing the 'zone of blighted living conditions'. [8] [media]The Depression of the 1890s and the intermittent nature and inadequate wages of working-class employment meant that Surry Hills families lived precariously close to real poverty. There was no margin to cater for unseen circumstances, and so sickness, unemployment or sudden widowhood could plunge a family into chronic destitution. And in coping with long-term poverty, many Surry Hills families were forced to adopt one or more of a range of mostly unpleasant survival strategies.

One was turning to charities, and the Benevolent Society and the Sydney City Mission, among others, were active in the area. But the charitable institutions never tried to attack the causes of working-class poverty, although they did rail strongly against its symptoms – alcoholism, gambling, prostitution and crime. The resort to crime was probably the most drastic of the survival strategies, and gave the area a long-lasting reputation, as did drinking and sex work. But the reality of prostitution was far less sensational that the lurid imaginings of the newspapers. For many women, sex work was an almost inescapable consequence of widowhood, desertion, long-term unemployment, or alcoholism.

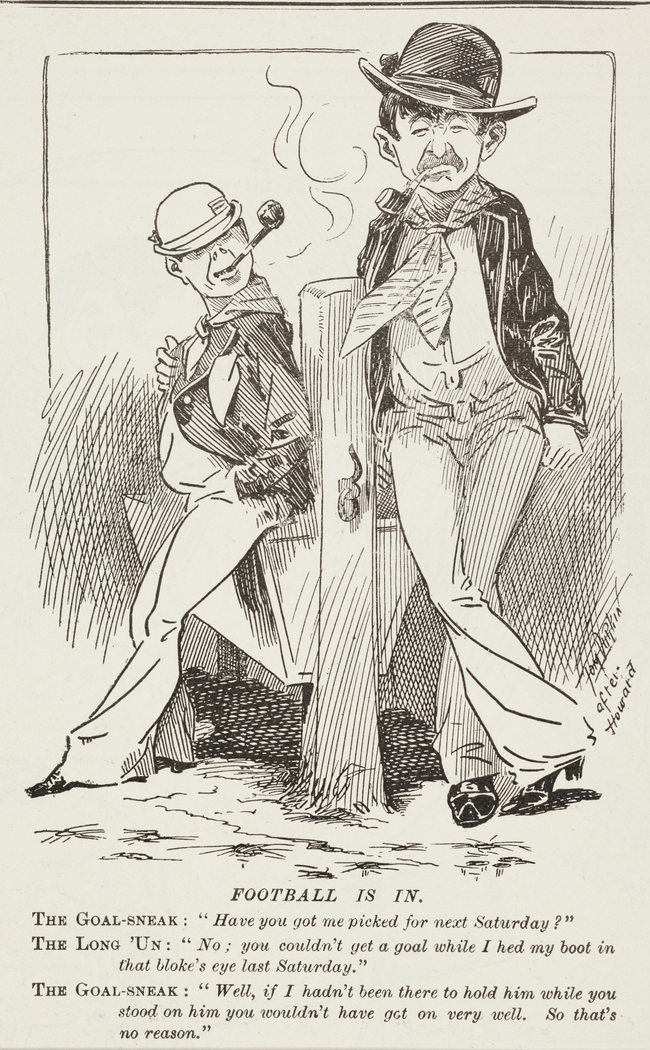

[media]'Crime' became a byword for Surry Hills. Probably most famous at the turn of the century were the larrikins. Such gangs had long been part of Sydney's history, and by the 1880s Surry Hills, like most inner-city neighbourhoods, boasted at least one local gang. Early in the twentieth century, Crown Street Public School had a reputation as providing a good grounding for prospective larrikins: the afternoons were spent collecting gravel, chunks of blue metal and half bricks ('Irish confetti' as it was affectionately known) which were used later in the evening for gangland battles.

But by the late 1920s and 1930s, the old-style larrikin gangs had largely been replaced by networks of organised criminals. 'Jewey' Freeman's Riley Street gang was thoroughly professional, and Riley Street itself was 'notorious as Sydney's worst thoroughfare and Underworld battleground'. [9] Ruthless gangs now employed shotguns and razors to snare a piece of the lucrative sly grog and cocaine trades. By the late 1920s, the much publicised locality of Frog Hollow was known as

a haven and a stronghold for some of the most desperate and dangerous criminals that police could recall. [10]

The names of criminals such as Kate Leigh, the so-called 'queen of the underworld', became well known far beyond the suburb.

Change and challenge

While the perceptions of what the area should be used for varied greatly over time, one constant for the first half of the twentieth century was 'remodelling and improving' the inner-city 'slums', particularly Surry Hills. In 1927 the City Engineer put forward another set of plans for the area:

the reduction of unnecessary streets…will give additional land for industrial purposes, and, consequently, additional revenue to the City Council. [11]

[media]One result was the Brisbane Street resumption, which disposed of a network of narrow streets with a bad criminal record. Other Surry Hills localities were also 'renovated'. By 1930 most of the houses in Frog Hollow had been demolished, and inhabitants were relocated, often to far-flung suburbs. For those remaining in Surry Hills, the onset of the Depression brought new challenges, with the maintenance of a roof over one's head the most pressing need. Working-class life in the area in this period was the focus of novels by writers whose social conscience was drawn to the inhabitants; Ruth Park in Poor Man's Orange and The Harp in the South, and Kylie Tennant in Foveaux.

Then came another war. As another generation of young men abandoned the factory bench or the dole queue for the battlefield, those people who remained behind learned to adjust to the rigours of wartime. Food and clothing coupons, daylight saving, identity cards – and petrol rationing for those who had cars – were now all part of life. In March 1942 the first shipload of American servicemen appeared in Sydney – 'oversexed, overpaid and over here' – and soon some of Surry Hills' most nefarious industries were flourishing. The area north of Oxford Street was off limits to black American troops, but they were accepted into the bars and brothels of Surry Hills, because 'Riley Street knew an underdog when it saw one'. [12] The influx of servicemen ensured that Kate Leigh, with her brothels and sly grog shops was 'riding high'. Her rival was Tilly Devine, whose own vice empire was north of Oxford Street.

The city was experiencing a housing shortage, due to the economic strictures of the depression and the government's wartime restrictions, so the value of inner-city land skyrocketed, governed now by prices obtainable for industrial not residential uses. [media]Factory encroachment saw much residential building demolished in Surry Hills, leading to a growing concern at the City Council about the provision of adequate affordable housing within its boundaries. Of four areas within the City designated as slums to be cleared, three were in Surry Hills: the old terrace housing there was seen as ripe for demolition, so that new public housing could be built. But it was stressed that housing, as part of postwar reconstruction, was a matter of national importance, for which Council could not take sole responsibility: nor could it afford to. So the Council's Devonshire Street Housing Scheme was taken over by the state government's Housing Commission late in 1947, in preparation for the construction of what the Minister for Housing claimed was the erection of Sydney's biggest block of flats, a 15-storey home to 1200 people.

[media]But new public housing was not the answer to the plight of Surry Hills. The late 1940s was perhaps the lowest point in a long period of deterioration in the suburb: its population had fallen to 19,000 – and continued to fall, reaching a mere 12,000 in 1974. Its [media]reputation preceded it: as a character in Ruth Park's 1948 novel The Harp in the South observed,

A Surry Hills girl finds it difficult to obtain a position in the city. She may be educated, she may be more highly moral than similar young ladies in more prosperous suburbs, but her address is against her. Most Sydney people persist, somewhat biasedly, in thinking of Surry Hills in terms of brothels, razor gangs, tenements and fried fish shops. [13]

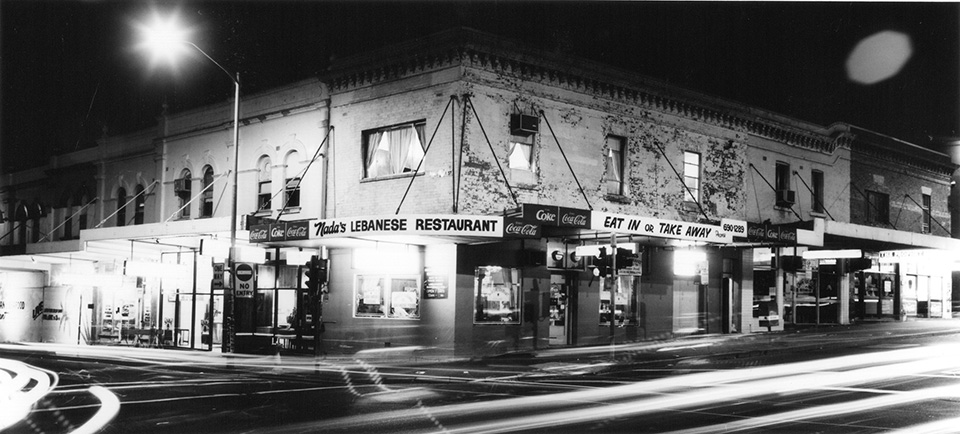

Of the families who could, many did leave the area in the 1950s, for greener pastures, and to be rid of the stigma which attached to the place. This exodus to the suburbs broke down many of the old social networks that had sustained generations of residents. But there was an unexpected light on the horizon, one that would ultimately prove to be the salvation of Surry Hills as a vital residential neighbourhood. [media]The postwar influx of migrants, particularly Greeks, Italians, Portuguese and Lebanese, breathed new life into Surry Hills, as they bought up the houses vacated by the old Australian families. Many of these newcomers worked long hours as shopkeepers or in the local factories: at the glass works, in the rag trades, or at Raleigh Park tobacco factory. They bought into Surry Hills because it was cheap and near places of employment and others of their own communities. This postwar generation rehabilitated Surry Hills as a viable residential suburb, helping invalidate the planning schemes that would have turned the area into an industrial and commercial wasteland interspersed by monolithic housing estates. Reflecting this, by 1970 about 70 per cent of the children at Bourke Street Public School were migrants or had migrant parents.

The return of the gentry

[media]The next influx of people into the area further hastened this process, helping turn Surry Hills and its terraces back into the desirable address it had been more than a century before. The gentrification of Surry Hills is not over, and its starting point cannot be easily identified, although it was underway from the late 1960s. These 'urbanites' were mainly young people, fleeing from suburbia, a new middle class who were self-employed, employees of the public service, corporations, the media or the universities, or in the professions. As one sociologist has noted,

they came to the inner-city looking for a cosmopolitan alternative to the suburban life [14]

By the 1980s these 'yuppies' were buying into the by-now chic terraces of Surry Hills.

[media]The gentrification of Surry Hills saw a momentous demographic change for the area, bringing with it a variety of tensions. Spiralling rents forced many older working-class and migrant families out; on the other hand, spiralling house prices allowed many previous residents to sell up and move out to less crowded suburbs. [media]And the newcomers brought with them skills that would ultimately benefit the whole of the neighbourhood. They were both articulate and vocal about their concerns; they were willing to confront those whose actions they disagreed with, including local councillors or state politicians. The 1970s saw the formation of dozens of resident action groups, groups which thought nothing of combining with militant unions or professional organisations to further their causes. What the residents of Surry Hills – old and new – had done was effectively to rezone the area themselves.

[media]Surry Hills underwent a further architectural transformation in the last decade of the twentieth century, with contemporary apartment buildings being added to the streetscape of historic terraces. The area west of Riley Street, once the traditional rag trade area, has now become a hub for media, design and professional services. Today, the area has evolved into a colourful and diverse place that is well known for its art galleries, antique dealers, cafes and pubs, fashion and rag trade outlets.

Once again, Surry Hills is home to the well-heeled middle classes.

References

Christopher Keating, Surry Hills: The City's Backyard, Halstead Press, Sydney, 2008

Notes

[1] A Phillip, The voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay: with an account of the establishment of the colonies of Port Jackson & Norfolk Island, Richmond, Hutchinson of Australia, Sydney 1982, p 51

[2] Terry Kass, 'The Builders and Landlords of Surry Hills 1830–1882', MA thesis, University of Sydney, 1984, vol 1, p 17

[3] Terry Kass, 'The Builders and Landlords of Surry Hills 1830–1882', MA thesis, University of Sydney, 1984, vol 1, p 27

[4] George Wigram Allen, Early Georgian: Extracts from the Journal of George Allen, 1800–77, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1958, p 84

[5] Jan Burnswoods, Bourke Street Public School, 1880–1980, NSW Dept of Education School Files, 1980, p 1

[6] R Connell and T Irving, Class Structure in Australian History, Longmans Cheshire, Melbourne, 1980, p 189

[7] A Jakubowicz, 'The City Game: Urban Ideology and Social Conflict', in D Edgar (ed), Social Change in Australia, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1974, p 334

[8] S Fitzgerald, Rising damp: Sydney 1870–90, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987, p 227

[9] Daily Guardian, 11 March 1926

[10] Sun, 13 September 1923

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 August 1927

[12] 'American loses 95 pounds at Surry Hills party', Daily Telegraph, 19 August 1943, p 9; Gavin Souter, Inside Surry Hills: A Tough Nut to Crack, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 February 1960, p 2

[13] Ruth Park, The Harp in the South, Penguin Books, Ringwood, 1975, p 138

[14] A Jakubowicz, 'The City Game: Urban Ideology and Social Conflict', in D Edgar (ed), Social Change in Australia, Cheshire, Melbourne, 1974, p 336

.