The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Glebe Pubs

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Glebe Pubs

The institutions of society in Glebe were largely a by-product of Victorian England. Brian Harrison argues that in England the pub was a place for male drinking rituals, for establishing one's virility by drinking deeply, and for being initiated into manhood. [1] Pubs and churches each housed congregations and both were complementary recreational outlets here as well as in Britain. But by the 1880s they came to be in competition.

The pub in nineteenth century Glebe was larger and more comfortable than the average working class home and it was just around the corner. The distribution of the pubs, concentrated in the poorer parts of Glebe, revealed something of the functions they performed. The respectable neither needed pubs nor encouraged them, for they would lower the tone of Glebe Point. If the respectable man wanted a drink he could go to his own sideboard, or to a club.

In 1891 in the ward of Outer Glebe there were 11 pubs for its population of 3,695; in Bishopthorpe, seven pubs for 5,402; Forest Lodge, five pubs for 2,554; Inner (Glebe Point), two pubs for 5,406 people. [2] By 1900 there were 424 pubs in the city of Sydney, one for every 264 people. In the suburbs there were 423 pubs, one for every 888 persons. [3]

Before 1880 the pub was an important public space, a forum for public meetings, church services, court sessions, dances, concerts, and theatricals. Aspirants for municipal office announced their intention to seek election at the pub within their ward, and advertised when they would be available for voters to hear how they would improve their neighbourhood. [4]

Beer was the basis of much leisure and drinking remained an accepted part of a working man's life. It was said that a normal ration was necessary 'to maintain his strength'. After all, if you can't have some enjoyment, then what is there to live for? [5] The offer of a drink was something that could not easily be refused as 'shouting' was a common form of hospitality, and an important and expensive adjunct of the pub ritual. The pub was not only a sociable place but a way out of the life its customers were leading.

Drinking and temperance

Drinking was not without its subtle social gradations, with inquiries distinguishing 'better class' public houses from mere 'drinking shops', dancing and singing saloons. [6] Respectable tradesmen did not frequent dancing saloons, observed John Read; [media]those were patronised by 'the lowest order of men and by young girls on the verge of prostitution.' [7] In 1865 Read observed boys and girls who frequented a Glebe dancing saloon 'in adjacent paddocks with their clothes deranged as if they were engaged in immoral practices' [8]. Bobby Hancock, licensee of the Lady of the Lake in Bay Street, Glebe, became part of local folklore. Hancock kept at least four mistresses at various times and often drove down George Street in a spanking carriage and pair with two of them together, one feathered beauty on each arm. Bobby retired to the seclusion of the Lady of the Lake where he died on 26 February 1876. His body was laid out on the tap room table, farthing candles placed at his head and feet, and patrons invited to drown their sorrows. After a wild wake, local imbibers followed the cortege to Rookwood Cemetery. [9]

In a parish that claimed many people from 'the humble classes of life', Rev Joseph Barnier of St Barnabas drew a sharp distinction between the respectable artisan and the class of people who lounged about the doors of Glebe pubs. Barnier complained that on his route to and from church on the Sabbath he was confronted by 'reeling men and blaspheming youth' on street corners outside pubs. 'Parramatta Street', he said, 'is unpleasant to walk through on Sunday.' [10] The temperance alliance argued there were too many pubs selling too much liquor and induced the New South Wales Government to set up the Intoxicating Drink Inquiry in 1886. It found that per capita, consumption of beer was rising, but the quantity of spirits consumed was falling. Recent research has found in the second half of the nineteenth century New South Welshmen drank less beer [media]and spirits than their British counterparts. [11]

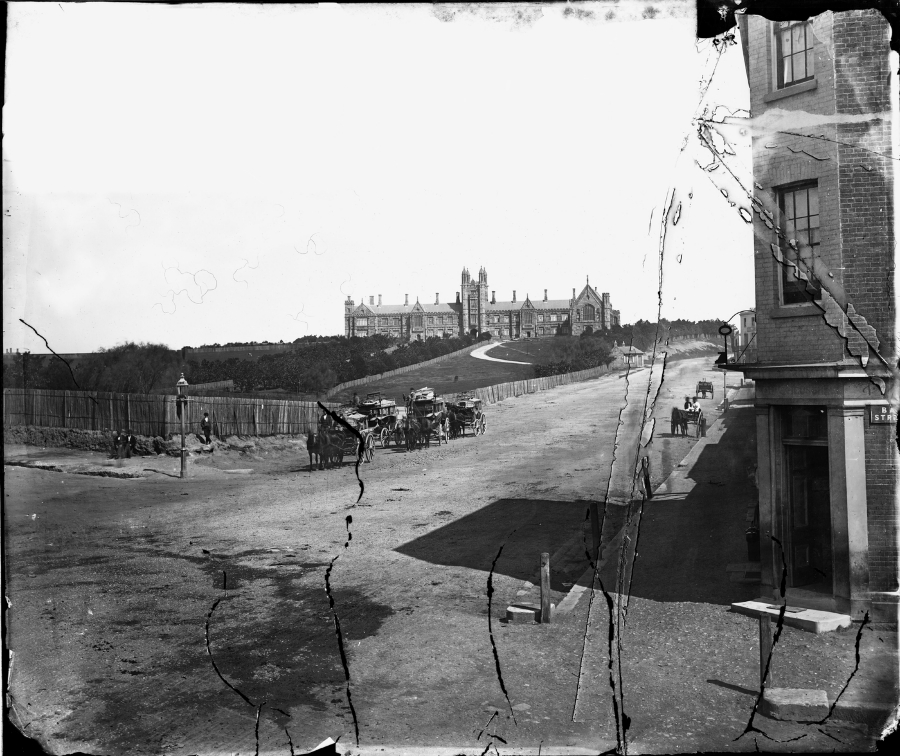

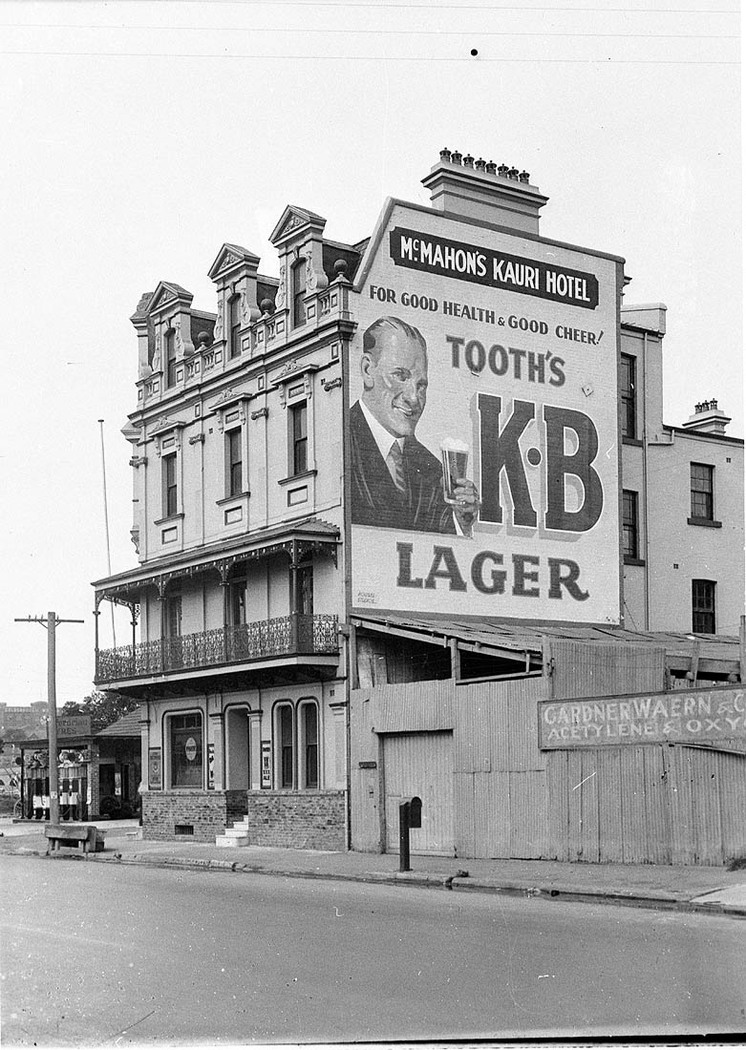

Glebe's [media]early pubs were small single storey buildings often located on street corners. From the 1880s large and highly ornamental two and three storey pubs appeared in Glebe. The University Hotel was the largest venue for local public meetings before 1880; much enlarged in 1889, it contained thirty four bedrooms, a billiard room, a public bar, four parlours and five shops. [12] Two more large and ornate pubs were built in the late 1880s. The Centennial (later the Harold Park), adjoining Lilliebridge Running Grounds, an important venue for professional athletics and pony racing, and the Grand (later the Kauri) drew patrons from burgeoning recreational activities at Wentworth Park.

The Licensing Act 1882

The pub was nearby, and always open, from 6 am to midnight from 1843 to 1881, seven days a week. Temperance drew heavily on evangelical religions for its rhetoric and fervor. The Glebe Road Wesleyans were the most active in seeking legislative restriction or prohibition of the liquor trade. The Licensing Act of 1882 embraced some of their demands. By making Sunday trading illegal, it forced drinkers to buy more bottled beer to see them through the weekend. The Act also introduced the concept of local options by which electors in municipal elections could vote as to whether they wanted to reduce or maintain hotel licences. [13] By 1900 the Women's Christian Temperance Union was concerned at the effect that alcohol had on homes and families, and it campaigned to reduce men's access to alcohol in licensed premises. They succeeded on both counts, and, in the process, reinforced the pub's place as a masculine space from which women were systematically excluded. Glebe supported twenty-eight pubs in 1892, one pub per 610 people but local option reduced pub numbers to twenty-three in 1901, and seven more pubs had closed their doors by 1914, leaving seventeen still trading. [14] In 1905, New South Wales Labor politician WA Holman saw temperance in class terms; it was, he said, a middle class attempt to suppress the centre of working-class social life, depriving workers of both a social place and a meeting place. [15]

Drinking, wives and family

Richard Waterhouse argues that in its increasing focus on domesticity, the working class had moved closer to the proclaimed middle class notion of respectability. Men who considered themselves respectable were careful to drink in moderation, and usually required that their wives either drink in private or refrain from alcohol altogether. [16] No respectable woman ever visited a public house but many drank beer, obtained from the bottle and jug department, in the privacy of their homes. In Sydney, perhaps a boilermaker might withhold 3 shillings from his weekly pay packet of £3 (a bit less than British sociologist Seebohm Rowntree's estimate for the English city of York in 1901), from money entrusted to his wife, and at threepence for a (10 ounce) glass in a public bar in 1914, he could drink twelve beers from Friday to Friday. [17] A husband's proclivity to drink ate into a very tight budget, and perhaps a majority of working men whom the rector of St Barnabas, Joseph Barnier, saw as 'steady and sober' in 1878 consumed much less than that. [18] To some workmen, drink came to mean more than a social life or an escape. The hard, unremitting physical toil of a wharf labourer, or the heat of an iron foundry, caused dehydration. A few drinks helped replenish lost fluids.

Pubs, breweries and Sunday trading

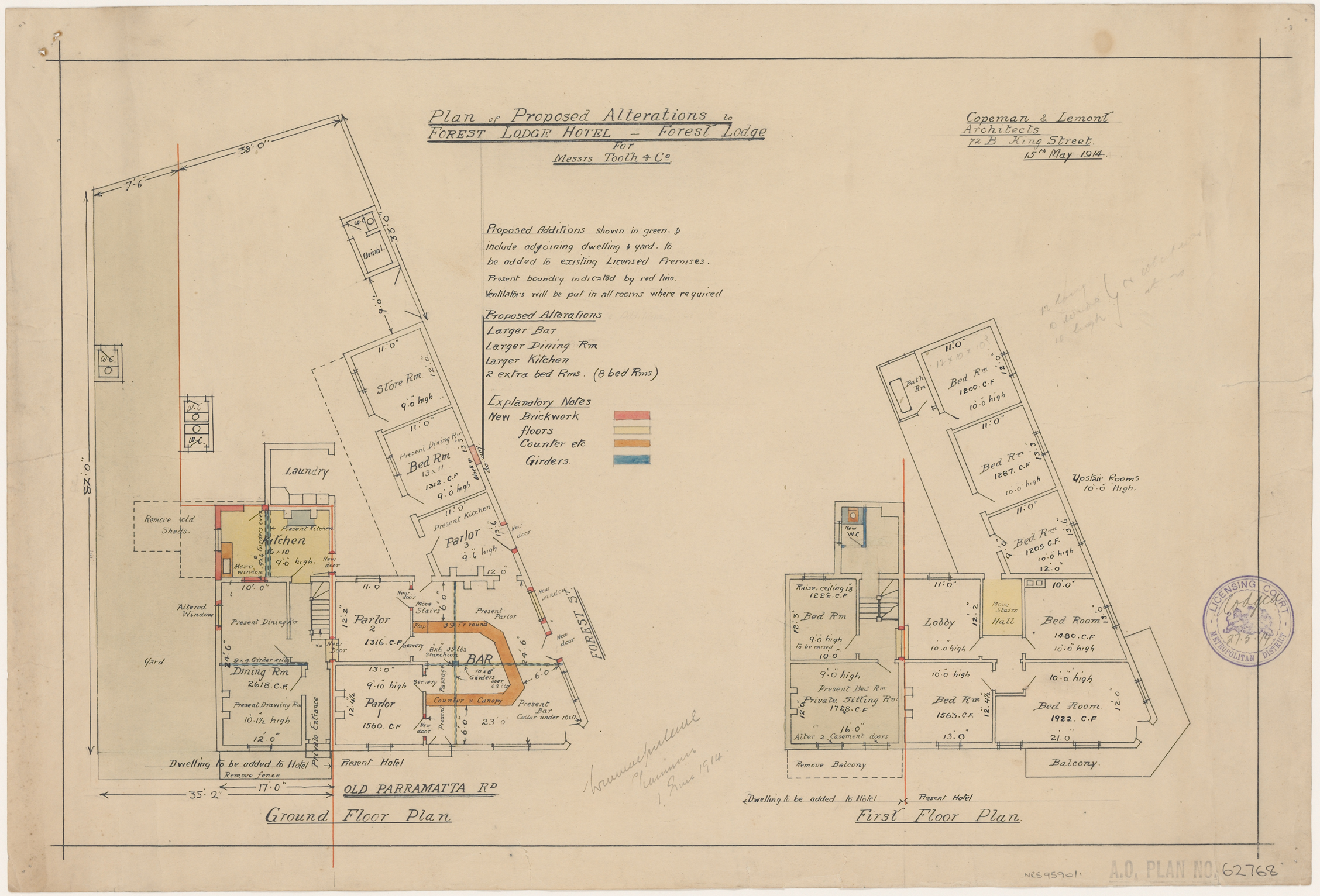

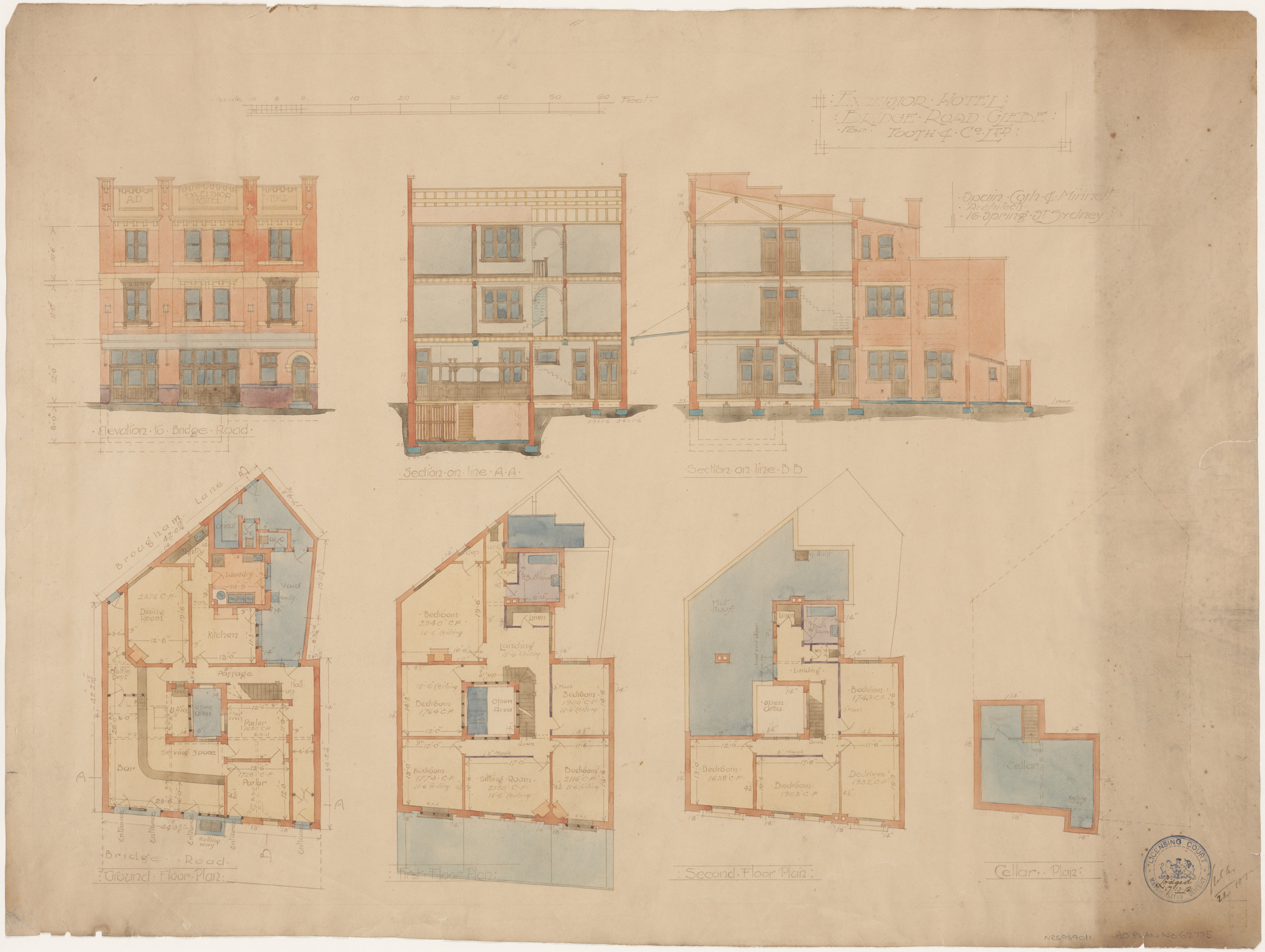

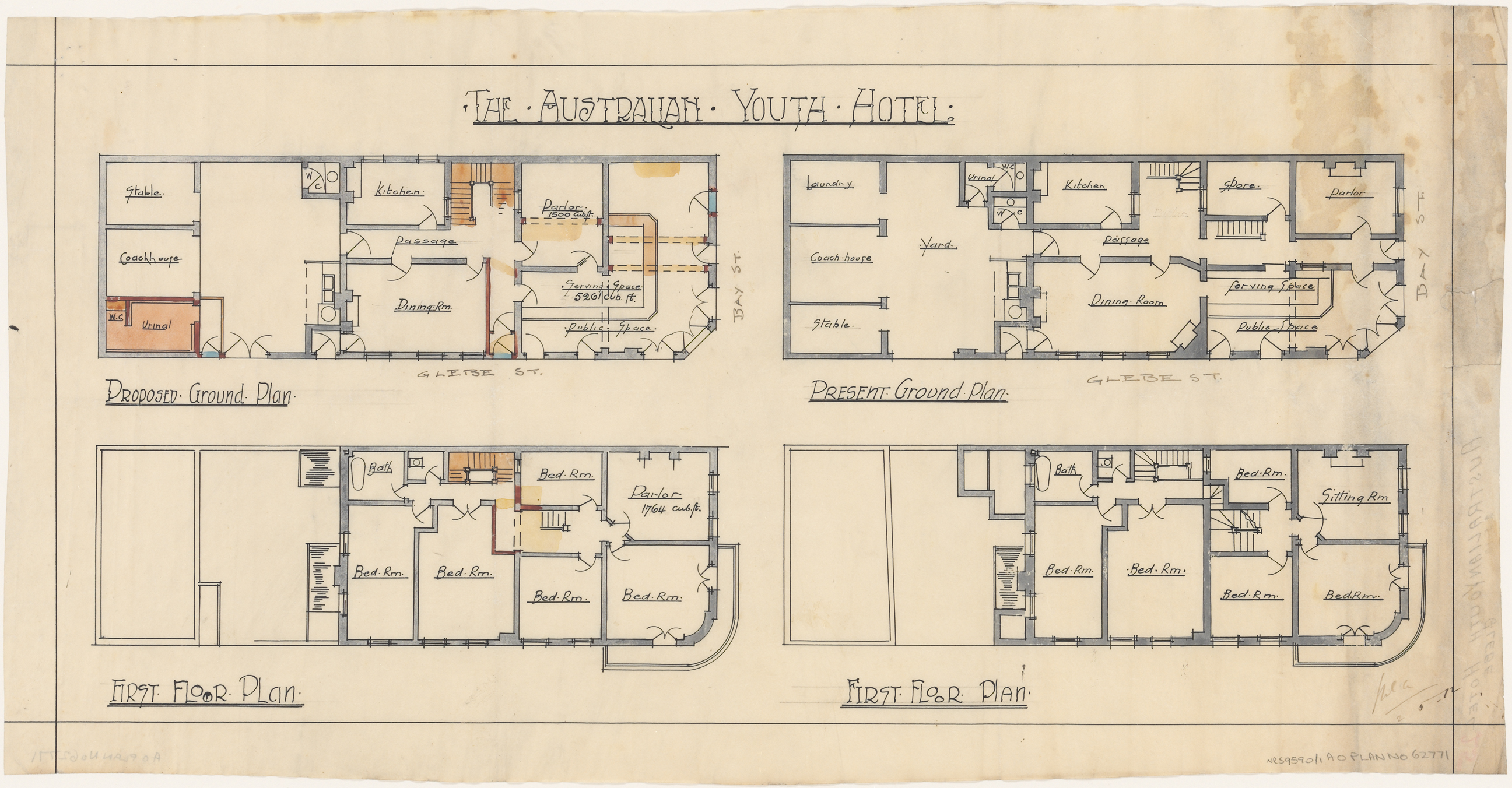

Publicans laboured long hours [media]to make a living. Most pubs were tied to breweries through ownership or leasing arrangements. Stephen Davoren, licensee of the Hand and Heart, was compelled [media]to buy all his beer, wines, spirits [media]and cordials from supplying brewer Tooth and Co, and they drove a hard bargain. Davoren, who sold eight to ten 36 gallon barrels a week and paid Tooths 8 percent on a loan of £1,750, told an inquiry that he made nothing out of the hotel business; 'I gave 16 years of my life to Tooth and Co', he said. [19] In 1900 police estimated that 80 per cent of Sydney's hotels traded illegally on Sundays, though the small number of convictions each year gave little indication. [20] Publicans, the focus of temperance attacks, were seen after the tied house inquiry in 1902 as pawns of the wealthy brewers who forced adulterated liquor onto the market, and whose power over publicans prompted breaches of the licensing laws. In Sydney, big breweries – Tooths, Tooheys and Reschs – merged into corporations, and became major hotel owners through the tied-house system. From 1898 Tooths began its move to control the drink trade in Glebe and by 1939 it had acquired the freehold of eight pubs – Lilliebridge (1898), Ancient Briton (1901), Forest Lodge (1905), Excelsior (1907), Australian Youth (1936), British Lion (1936), Friend in Hand (1936) and Kauri (1939), and it acquired the head lease of the University Hotel in 1926. [21]

In 1901 a fair-haired former member of the Scottish constabulary, Sergeant James Hogg, moved to Glebe and set out to catch publicans trading on Sunday or after hours. Hogg dispensed with his heavy boots for sandshoes, and invariably conducted his raids on a wet evening when, with umbrella pulled down over his head, he was not readily detected by cockies, as lookouts were termed. 'Hogg by name, Hogg by nature', drinkers muttered as Hogg's successes mounted. [22] This intolerable interference with local drinking habits could not continue; in 1902 allegations were made that Hogg, the terror of imbibers, had used a skeleton key to gain entry to Mary Gee's Excelsior Hotel at 101 Bridge Road Glebe. A Royal Commission found the allegations against Hogg were without foundation and were simply an attempt to have him removed from the district. [23]

A beery aura always hung round the Ancient Briton which sold more beer than any other Glebe pub. Its licensee from 1903, Michael Furlong, would not tolerate any drunkenness or bad language in his pub. At the other end of the spectrum, dancing saloons remained the stronghold of the poorest strata of society. [24] No self-respecting workman would be seen entering the Sir George Grey in Bay Street.

Publicans and local groups

The close associations that developed between publicans and local sporting and other groups were hardly the result of disinterested philanthropy. Early football clubs were formed and met at Durrell's (later May's) Family, but by 1900 local cricket, rugby union and bicycling clubs held their annual meetings in the long room of the University Hotel, attracted there by its gregarious licensee, Billy Bulfin. Glebe Soccer Club was based in the Excelsior while the upper rooms of the Currency Lass were filled once a month by members of the Wentworth Masonic Lodge. [25] Labourers from the wharves, iron foundries and wool stores, crowded into the bars of Walter Burke's Friend in Hand and Tom Crowe's Australian Youth. The Kauri was a popular place for timber workers. Forest Lodge manual workers loyally supported the British Lion and Forest Lodge, while Labor activists and unionists conducted meetings in the Albion and Excelsior. [26]

In the benign world of the neighbourhood bar, patrons were known by name and often had their own seats. At the Burton Family there was an empathy between regulars and the publican Frank Flitcroft (known as Cranky Frankie or Knackers O'Brien). The Glebe Rugby League Club met and changed at the Burton Family, and Frankie's wife Ettie handed out maroon ribbons to pin on lapels and trophies for players. [27] Drag picnics, as they were called, were regularly organised at the Burton. This involved loading a 36 gallon keg of beer on a horse-drawn double decker bus and heading off on fishing trips, often to Sans Souci, or going to some recreational ground for a game of cricket. The Burton Family thrived on the football connection. The annual number of beer barrels emptied at Flitcroft's pub increased from 235 in 1902 to 347 in 1908. From 1911 to 1913, great seasons on the field for Glebe Rugby League, more than 600 barrels of draught beer were consumed each year. Bottle sales also rose impressively.

Tooth's brewery maintained a detailed record of beer sales of the Glebe pubs tied to Tooths. Patrons of a local pub that closed generally transferred their loyalty to another local, often the closest to their home. As a consequence, beer consumption at the surviving pubs tended to rise.

Six o'clock closing

The temperance movement saw the outbreak of war in 1914 as a godsend by which they could urge their panacea – pub closures or reduced trading hours. A referendum in June 1916 indicated that within Glebe, opinions on drinking varied greatly. At Derby Place and Mitchell Street polling booths people voted overwhelmingly for 9 o'clock closing, but at Toxteth Road booth residents favoured 6 o'clock closing by a two to one ratio. Figures at St Johns Road booth were evenly divided. [28] In the City of Sydney, a bastion of popular culture, 58% favoured 9 o'clock closing. [29] Six o'clock closing won and remained until 1955, changing the whole culture. The pub ceased being a centre of the common man's community life. Increasingly, billiard tables, dart boards, quoits and skittles were removed to accommodate large crowds that gathered in the hour before closing time. The physical layout of pubs changed as they became no more than high-pressure drinking houses. Caddie, a barmaid in Sydney in the inter-war years wrote of 'the shouting for service, the crash of falling glasses, the grunting and shoving crowd, and that loud indistinguishable clamour of conversation found nowhere but in a crowded bar.' [30]

Women in pubs

Women, as barmaids, became creations of men's fantasies, objects of desire to a masculine gaze, and an integral part of the pub's masculine culture. FB Boyce regarded barmaids as nothing more than a lure: 'a pretty girl is frequently engaged to attract soft young men, and keep them hanging about the bar.' [31]

As ideas about appropriate womanhood within the new nation gathered momentum after 1900, the barmaid as a wage-earning woman was inconsistent with the familial ideal of men as breadwinners. However, by the 1920s the barmaid was being seen as a serious working woman, demanding respect. [32] The public house, a place where domestic and commercial activities were interconnected, allowed a number of Glebe women to earn a respectable and prominent living as hotel keepers – Annie Brennan, Honora Delohenty, Annie Egerton, Alice Flitcroft, Mary Gee, Margaret and Kathleen Toohey, Elizabeth Saunders and Margaret Smyth.

The masculinity of drinking and pub culture was enshrined in law, with women required to drink in 'Ladies' Lounges', physically separated from the public bar. Three local pubs did not survive the inter-war years – the Winchester, the Imperial and the Glebe Tavern whose licence was transferred in 1934 to the new Toxteth Hotel. [33]

The prohibition poll

Drink was blamed for unemployment by the temperance advocates in the public debate leading up to the Prohibition poll in September 1928. But anti-prohibitionists counter-attacked, claiming prohibition would foster organised crime. They won the day and the pub trade struggled throughout the depression. The threepenny counter lunch, a feature of nineteenth century pub life, was reintroduced to boost custom. But the emphasis remained on drinking, and with 30% unemployment, beer consumption per head declined. [34]

The 1951 Royal Commission and changes to Glebe's pubs

Concerns about corruption in the retailing of beer through the pubs led the New South Wales Government to establish a Royal Commission on Liquor Laws in New South Wales in 1951 to inquire into all aspects of liquor trading. The Commissioner, Justice Maxwell, took evidence from over 400 witnesses, and the report was presented to Parliament three years later. [35] Maxwell's most significant finding was in relation to the appalling conditions under which men were forced to drink. 'I am satisfied', reported Maxwell, 'there are evils associated with 6 o'clock closing which ought not to be tolerated in a civilised community.' He was scathing about the deceitful practices of pub owners; 'I have little doubt that licensees will in many...instances, favour the retention of 6 pm closing because the return from the sale of liquor is obtained more quickly than with the burden of supervision and added labour involved in later hours. [36]

Maxwell's report led to entirely new drinking practices and supported 10 pm closing which came into effect in February 1955, offering food, entertainment, and access for women. The rapid growth of licensed clubs threatened the existence of pubs; by 1962 there were 1,285 clubs in New South Wales, many with poker machines, legalised in 1956. Sixteen pubs were operating in Glebe in 1947, but five pubs, established during the nineteenth century, ceased trading between 1955 and 1967 when their 99 year leases expired. These were the Bridge (1955), and four pubs on Bishopthorpe Estate – the University, Currency Lass, Kentish and May's Family. Closure of the Harold Park Hotel in 1998, and transference of the Burton Family's licence to Casey's in 2003 (now the Doghouse) left ten pubs trading in Glebe.

Further reading

Boyce, Francis Bertie. The Drink Problem in Australia: The Plagues of Alcohol and the Remedies. London: National Temperance League Publication Department, 1893.

Harrison, Brian. Drink and the Victorians: The Temperance Question in England 1815–1872. London, Faber and Faber, 1971.

Kirby, Diane Barmaids. A History of Women's Work in Pubs. Cambridge, UK; Melbourne, Vic: Cambridge University press, 1997.

Rowntree, B Seebohm, Poverty: A Study of Town Life. London: Macmillan and Company Limited; New York: The Macmillan Company, 1902.

Solling, Max. Grandeur & Grit: A History of Glebe. Sydney: Halstead Press, 2007.

State Records of New South Wales. NSW Parliament, NRS 1580 Report of the Commissioner, Royal Commission on Liquor Laws in New South Wales, vol 1, 1954.

Tooth and Co records. Noel Butlin Archives Centre, Australian National University. http://archives.anu.edu.au/collections

Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1887/88.

Waterhouse, Richard. Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788. South Melbourne, Vic: Longman 1995.

Wright, Catherine Edmonds. Caddie: The Autobiography of a Sydney Barmaid, Written by Herself with an Introduction by Dymphna Cusack. London: Constable, 1953.

Notes

[1] Brian Harrison, Drink and the Victorians: The Temperance Question in England 1815–1872 (London, Faber and Faber, 1971) 39, 187

[2] Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1887/88, vol 7, 526

[3] Richard Broome, Treasure in Earthen Vessels: Protestant Christianity in New South Wales Society, 1900–1914 (St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 1980), 142

[4] Max Solling, 'The Pubs of Glebe,' Leichhardt Historical Journal 6 (1975): 10–15

[5] Richard Hoggart, The Uses of Literacy: Aspects of Working Class Life (London: Penguin in Association with Chatto and Windus, 1957), 95

[6] Evidence of Rev J Barrier to Select Committee on Sunday Sale of Liquor Prevention Bill, Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1877/78, vol 4, 893

[7] Evidence of John Read to the Intoxicating Drink Inquiry Commission, Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1887/88, vol 7, 153

[8] Evidence of John Read to the Intoxicating Drink Inquiry Commission, Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1887/88, vol 7, 153

[9] Geoffrey Scott, Sydney Highways of History (Melbourne: Georgian House, 1958), 56–59

[10] Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1877/78, vol 4, 893

[11] AE Dingle, 'The Truly Magnificent Thirst: An Historical Survey of Australian Drinking Habits', Historical Studies 19 (1980): 231–33

[12] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 March 1879, 14

[13] Richard Broome, Treasure in Earthen Vessels: Protestant Christianity in New South Wales Society 1900–1914 (St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 1980), 141, 147

[14] Sands Directory (1892, 1901, 1914)

[15] NSW Parliamentary Debates, 30 October 1905, vol 20, 2591

[16] Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788 (South Melbourne, Vic: Longman 1995), 83

[17] B Seebohm Rowntree, Poverty: A Study of Town Life (London: Macmillan and Company Limited; New York: The Macmillan Company, 1902), 31–25.

[18] Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1877/78, vol 4, 893

[19] Evidence of S Davoren to Select Committee on Tied Houses, Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1901, vol 6, 814–18

[20] NSW Police Department Report 1904, Votes and Proceedings NSW Legislative Assembly 1905, vol 3, part I, 233

[21] Tooth and Co Library, Noel Butlin Archives Centre, Australian National University, http://archives.anu.edu.au/collections

[22] JF Flitcroft, Interview with Max Solling, 30 April 1983

[23] Royal Commission to Inquire into a Charge Against Sergeant James Hogg of the Police Force, Journal of NSW Legislative Council 1891/92, 1902, part 2, 9–36

[24] JF Flitcroft, Interview with Max Solling, 30 April 1983

[25] Sydney Morning Herald, 30 March 1881, 5; Sydney Mail, 14 April 1900, 892; Sydney Sportsman, 29 October 1903, 3; Sydney Freemasons, Centenary History of Lodge Wentworth 1881–1981 (Sydney: Lodge Wentworth, UGL, NSW, no 89, 1981), 16–17

[26] Australian Workman, 2 May 1891, 3; 16 May 1891, 2

[27] JF Flitcroft, Interview with Max Solling, 30 April 1983

[28] Sydney Morning Herald, 12 June 1916, 10

[29] Walter Phillips, 'Six O'Clock Swill: The Introduction of Early Closing of Hotel Bars in Australia', Historical Studies 19 (1980): 252

[30] Catherine Edmonds Wright, Caddie: The Autobiography of a Sydney Barmaid, Written by Herself with an Introduction by Dymphna Cusack (London: Constable, 1953), 8

[31] Francis Bertie Boyce, The Drink Problem in Australia: The Plagues of Alcohol and the Remedies (London: National Temperance League Publication Department, 1893) 139

[32] Diane Kirby, Barmaids. A History of Women's Work in Pubs (Cambridge, UK; Melbourne, Vic: Cambridge University press, 1997), 126, 134

[33] Tooth and Co records, 1934, Noel Butlin Archives Centre, Australian National University, http://archives.anu.edu.au/collections

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 23 May 1928, 31 May 1928; Diane Kirby, Barmaids. A History of Women's Work in Pubs (Cambridge, UK; Melbourne, Vic: Cambridge University press, 1997), 146

[35] State Records of New South Wales, NSW Parliament, NRS 1580 Report of the Commissioner, Royal Commission on Liquor Laws in New South Wales, vol 1,1954, 51–155

[36] State Records of New South Wales, NSW Parliament, NRS 1580 Report of the Commissioner, Royal Commission on Liquor Laws in New South Wales, vol 1,1954, 51–155

.