The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Darlinghurst

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Darlinghurst

Darlinghurst lies on the edge of the City of Sydney. Although sometimes confused with its illustrious neighbour, Kings Cross, Darlinghurst is a place in its own right. It occupies a wedge to the east of the city, situated between Woolloomooloo, Kings Cross and Surry Hills, although its boundaries have not always been so clear. The name Darlinghurst applied to Kings Cross, Potts Point and Elizabeth Bay for much of the nineteenth century, while some was previously regarded as part of Woolloomooloo. By the twentieth century however, its present boundaries had been defined.

It is bounded by William Street in the north, Hyde Park in the west, Oxford Street to the south and the appropriately named Boundary Street in the east, with Paddington beyond. Its elevated situation gave rise to its first naming by Europeans as Woolloomooloo Heights, while those areas closest to the city have recently been more often referred to as East Sydney.

Prior to the arrival of Europeans the area was within the traditional lands of the Gadigal people and they continued to visit and use the place into the 1840s when settlement by Europeans took hold.

Although the Darlinghurst area is close to Sydney it was not developed by Europeans in any great extent until the first decades of the 1800s. Rocky ridges and shallow soil made the area less attractive for the early settlers than other more productive, arable sites. The sandstone ridges did however provide stone for the expanding town, quarried by convict gangs. Stone continued to be extracted from the steep ridges into the second half of the nineteenth century, with prisoners from the nearby Darlinghurst gaol working the quarries. [1] Exposed sandstone faces, with houses perched above in the streets climbing up out of the valley to the ridge, remain in Darlinghurst as evidence of these early labours.

Wind and water mills

[media]The topography is important. The ridge looks out over the valley, once the back end of Woolloomooloo, now Darlinghurst/East Sydney, the differential being that the ridge was for the wealthy and valley was where most of the people lived. The streets were built across what were timbered and grassy slopes. Early maps show a number of streams running down from the heights towards the harbour. One of these is remembered in Stream Street behind the Australian Museum.

The colony's first water mill, that of Thomas West, was erected in 1811 and officially set going by Governor Macquarie in January 1812. Although West's mill stood in the valley of Rushcutters Bay, over the ridge line, it was soon joined by windmills on the ridge [2] taking advantage of the breeze sweeping in from the harbour. In about 1819 a merchant, Thomas Clarkson, had erected a windmill near what is now the intersection of Liverpool and Darley streets. This appears to be the first windmill in Darlinghurst, a stone mill with a mechanical turning head to catch the wind. Close by, two post mills were built, their design allowing them to be turned to face the wind. [3] A fourth mill was built by Thomas Hyndes on his allotment close to Caldwell Street. [4] The windmills were prominent features of the landscape, often depicted in colonial paintings of the town. The last of the mills to be demolished, reportedly around 1873 was the Craigend mill, built close to Thomas Mitchell's Craigend villa. The mill stood on the highest point of the ridge and was clearly visible from Sydney. Its position is reported to have been at the top of Beare's Stairs in Caldwell Street, east of Victoria Street. The mill's building materials were possibly used to construct four terraces in Caldwell Street and maybe the stairs themselves. [5]

Naming the place and moving in

[media]The name Darlinghurst was bestowed upon the ridge, previously referred to as Woolloomooloo Hill, or sometimes Eastern Hill, in the late 1820s by Governor Ralph Darling, thought to be in honour of his wife, Eliza Darling. The governor had selected the ridge line as a place for the construction of a series of fine villas, meant for members of the colonial elite. Between 1828 and 1831 Governor Darling issued 17 grants extending from what is now Surrey Street and Tewkesbury Avenue in Darlinghurst north to the end of Potts Point. As the land was granted to wealthy merchants, public servants and private citizens, the Governor stipulated conditions for the buildings. All plans had to be approved by him prior to construction, all houses had to be to a value of £1000 or more, and allotments could contain only a single residence with no other buildings, set within a landscaped garden and where possible, facing the town. The result was a collection of whitewashed villas, clearly visible on the main ridge to the east of the town.

The houses would be the symbol of a new high status area and 'serve as both an example and chastisement to the debased populace of Sydney Town'. [6] They would proclaim the growing wealth of the community and the potential opportunities to all those free settlers and merchants who sailed into the harbour. The Sydney Gazette on 20 April 1833 summed the whole idea up nicely when it proclaimed:

The hill of Woolloomooloo, formerly a frightful picture for the eye to rest upon from Sydney, is at length stripped of its sombre covering and begins to present to the view the most pleasing prospect, from the number of gentlemen's seats and tastefully laid out gardens which appear scattered over it. [7]

Of the 17 villas erected, four lay south of what is now William Street within the Darlinghurst boundary. These were Barham, designed by John Verge for Edward Deas Thomson, Clerk to the Executive and Legislative Council and later Colonial Secretary; Craigend, designed by and built for Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell; Rose Hall, the house of Ambrose Hallen Town Surveyor and Colonial Architect (Hallen designed Rose Hall himself); and Rosebank, likely designed by John Verge and built for Deputy Commissary-General James Laidley. Although all made it to the twentieth century, only Barham survives, within the grounds of the Sydney Church of England Girls' Grammar School (SCEGGS).

[media]The houses were all completed by the mid-1830s, and while they were symbols of what could be achieved in Sydney Town, they were also potent symbols of what could be lost. By the mid-1840s, the bottom had fallen out of the property market as the colony entered a recession. The restriction of only one building per allotment was challenged, and soon the first subdivisions began to appear. Sir Thomas Mitchell was the first to sell up, subdividing part of his estate as early as 1837. James Laidley had died in 1835 and his estate was sold on to Robert Campbell.

[media]These grants were also affected by the creation of William Street, which opened to traffic in 1840. Thomas Mitchell had surveyed a street alignment for easier access to the villas from the town. The road was to follow a gradual incline, heading off the South Head Road, put through in 1811, and approach the Darlinghurst area from the south, crossing a number of estates. The plan was opposed by Alexander Macleay, Thomas Barker and Thomas West, none of whom wanted the new street passing through their property. [8] The interests of private property were strong in Sydney and the result was that while Mitchell was out of town surveying the colony, his plan was compromised. William Street ran directly across the Woolloomooloo valley and up the steepest part of the ridge, in the process severing the northern ends of Barham, Rose Hall, Rosebank and Mitchell's Craigend estates. The new street also established the future boundary of Darlinghurst and Kings Cross.

Meanwhile, in the valley below, subdivisions were already underway on the larger Woolloomooloo estate. In contrast to the ridge, the lots in the valley were smaller and by the 1850s, rows of terraces had been built for workers, artisans and labourers. By 1854 Woollcott & Clarke's map of the city shows the developing suburban pattern, with streets and lanes clustered together in the western part of the suburb, close to the city. [9] William Street was the main thoroughfare and was at this time dominated by private houses, as was the rest of the suburb. A correspondent to 'Old Chum' as published in the Truth newspaper, recalled William Street in the 1860s, noting that it, with

few exceptions, contained nothing but private houses, and these were occupied in most instances by well-to-do citizens....William Street was the natural highway to town. It was quite a sight to see the beautiful equipages of the wealthy passing to and from the city on a sunny afternoon. [10]

Back from the main road, the lesser streets of Darlinghurst, south of William Street to South Head Road (Oxford Street), were beginning to take on an altogether different character. During the same period recalled by Old Chum's correspondent, the social commentator William Stanley Jevons wrote at some length on the developing neighbourhoods in 1858. Jevons noted that while William Street certainly contained some superior residences, a few inferior ones were mixed in, as well as retail shops. Venturing from the main road he observed:

The part of Woolloomooloo lying between William Street and the South Head road is almost entirely residentiary [sic]chiefly of second class, but in some parts, especially towards Darlinghurst with an inter-mix of third....a series of very narrow back streets have been formed of which a part is altogether shut in at each end as in the figure. These back streets, originally perhaps intended only to afford a second back entrance to the principal houses are rapidly becoming built up by additional smaller houses: in time they will form crowded dirty lanes, removed from the public view, difficult to drain and ventilate, and little better than closed courts. [11]

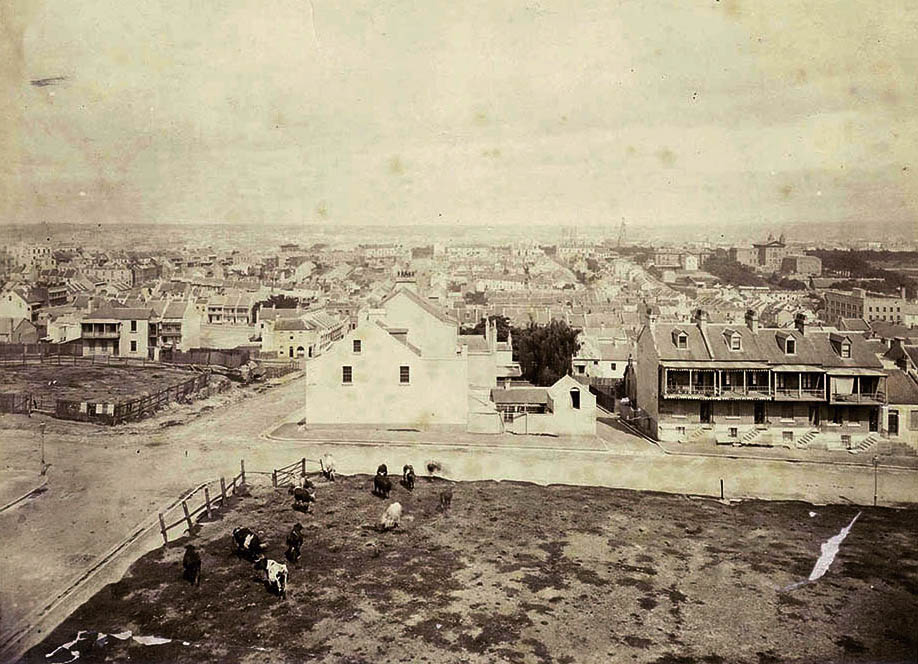

By the mid-1880s, most of the available land below the cliffs south of William Street was completely developed with residential terrace houses. Long strips of terraces housed workers and their families, many finding work around the wharves of Woolloomooloo Bay and associated industries. As demand for land grew and the larger allotments were re-subdivided; back lanes originally laid out for rear access were developed with smaller terraces fronting the lanes. In this way, Darlinghurst filled with dwellings, many of which were later considered slums. On the heights, the villas, also under pressure for redevelopment, managed to hold out into the 1880s. [media]Photographs from one such villa, Hilton, owned by John Rae, show cows grazing on the corner of Liverpool and Forbes Street in 1879, while beyond the terrace roofs of Darlinghurst stretch to the city.

[media]Many of the larger houses in the suburb were converted into boarding houses, from the 1890s, to accommodate an increasing population of itinerate workers, those attempting to find permanent jobs and the less well off. In 1911 the Darlinghurst and Woolloomooloo area included 182 boarding houses of varying sizes, 148 of which were run by women. [12]

Residential flat buildings became a feature of the city's landscape from the early 1920s, and to some extent this occurred in Darlinghurst. Flats appeared in particular around the periphery near Kings Cross, behind Darlinghurst Road and around the corner of Liverpool and Forbes streets. Elsewhere however, the terraces survived and remain the dominant dwelling type.

The institutions

[media]A feature of the development of Darlinghurst in the nineteenth century was the number of major public and religious institutions that were built on its fringes. The first was Darlinghurst Gaol, begun in 1822 (designed in sections by Mortimer Lewis, George Barney and James Barnet). The site chosen for the gaol was at that time on the very fringe of the settled area. Known initially as the Woolloomooloo stockade, the gaol was completed in 1841 and the prisoners marched from the old gaol in the city, along the South Head Road (Oxford Street) to their new abode. As well as the gaol, a new courthouse building was constructed on the site between 1835 and 1844, facing the South Head Road. [media]The Courthouse, like the gaol, was designed in sections by Mortimer Lewis and James Barnet. The gaol and courthouse together displayed colonial justice and punishment to all who passed by. Public hangings were a crowd-pleasing spectacle at the front of the gaol until they were moved inside in 1853. [13] The gaol continued to house her majesty's inmates until finally closing in 1912. The old prison building continued to serve as a technical college, which opened in 1921 and is now the National Art School.

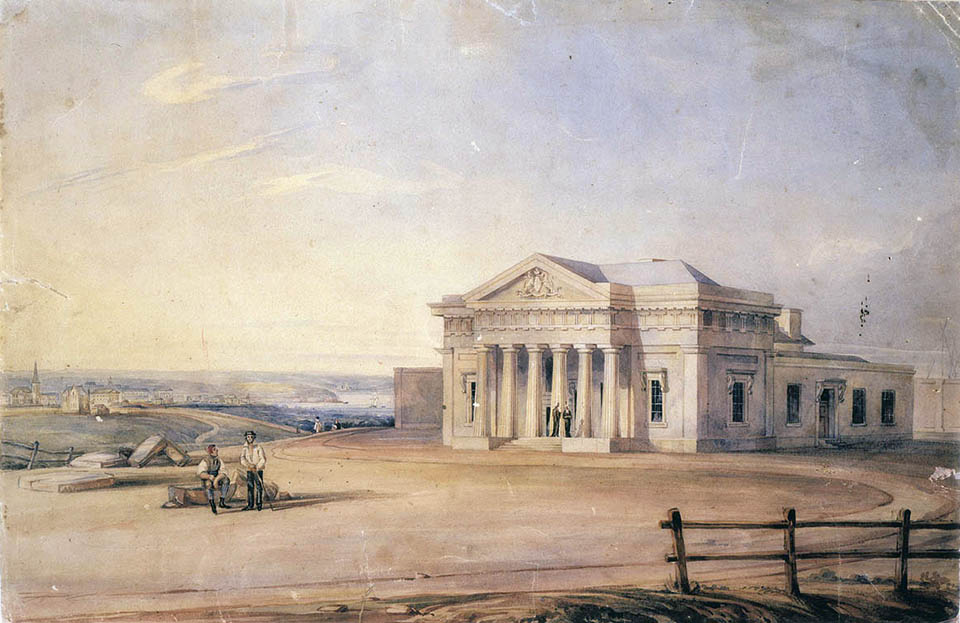

[media]On the western edge of Darlinghurst overlooking Hyde Park, the opening of Sydney College (designed by Edward Hallen, with later additions by Edmund Blacket and EA & TM Scott) in 1835 gave its name to College Street. Later renamed Sydney Grammar School, the Sydney College was the school of choice for Sydney's well-to-do; many boys from the Darlinghurst villas attended. Adjacent to the College, the first public museum in Australia, the Australian Museum, was started in 1846 and opened to the public in 1857. The museum's imposing edifice facing both College and William streets acts as a gateway building to Darlinghurst.

[media]In addition to Sydney Grammar, the Darlinghurst area was also served by the Sydney Church of England Girls' Grammar School (SCEGGS), which occupied the old villa of Barham in Forbes Street from 1901, and the Marist Brothers High School on the corner of Liverpool and Darley streets from 1911. While SCEGGS remains, the Marists moved on in 1968, and the school was converted to residential flats. These large boarding schools were the domain of the middle and upper classes. The local workers were more likely to send their children to the Superior Public School in William Street, established in 1851, next door to the museum on the corner of Yurong Street. Darlinghurst was a beneficiary of the select committee into public education which recommended the establishment of state-run non-denominational schools. In 1928 the school was redesignated as an Intermediate High School and functioned as the William Street Girls Junior High School, from 1929 until its closure in 1950. [14] The main school building, facing William Street still stands, as does a rear extension, both now incorporated into the Australian Museum as storage and office space. Other smaller school buildings facing Yurong Street and to the rear of the main school have been demolished.

Near the gaol and courthouse, the Sisters of Charity opened St Vincent's Hospital in 1870. [15] The hospital relocated from one of the old villas, Tarmons, at the north end of Victoria Street, where it had been established in 1857 as a free hospital for the poor of Sydney. [media]The new purpose-built St Vincent's was situated at the Darlinghurst end of Victoria Street, opposite the walls of the gaol. The hospital has continued to grow and expand, and in 2010 it occupied the entire Victoria Street block between Oxford and Burton streets.

Six major church buildings were also set within the neighbourhood, guiding the spiritual life of the inhabitants. The earliest and most imposing was St John's Anglican church, set between Victoria and Darlinghurst streets on the ridge line. The site for St John's had been dedicated to the Church of England in 1839 and construction began first on the Church of England St John the Evangelist Parochial School building in May 1851. The foundation stone for the church was laid in December 1856 and it opened, unfinished internally, for Easter service in 1858. [16] The first section was designed by Sydney architects Goold and Hilling. The church was extended in 1866 and the tower and spire finally added in 1872 to Edmund Blacket's design. Work on the inside continued throughout the remaining years of the nineteenth century, much of it financed with donations from wealthy members of the congregation such as the Tooth family. In 1905 the church was finally consecrated, three years before its 50th birthday. The school closed in 1965, a result of declining numbers of students. [17]

[media]Not far away on the corner of the South Head Road and Darlinghurst Road the Catholics were also planning a new church. The foundation stone for the Sacred Heart Church was laid in May 1850 and the church opened and consecrated in June 1852. [18] In 1880 work also began on an adjoining school, which was run by the Sisters of Charity. The school was two storeys, the upper floor for girls and the lower section for boys. In 1909 negotiations between the Church and the City began over the Council's widening of Oxford Street, which had been underway since 1907, starting from the city end. The church was in the way of the widening. Prolonged negotiations over the amount of compensation to be paid eventually led to Sacred Heart's demolition in 1910. The Catholic Church received £5,788 for the site. [19] In October 1911 the foundation stone for the new church, designed by James Nangle, was laid and the building completed by November 1912. Sacred Heart school continued to teach until its closure in 1986. Notre Dame University has taken up residence at Sacred Heart in 2009.

In July 1867 St Peter's Anglican church in Forbes Street was consecrated 14 months after the foundation stone had been laid. Built in the valley amongst the terraces, St Peter's served the working congregation rather than the more genteel residents of the Darlinghurst heights area. The church was deconsecrated in 1993 and is now used by SCEGGS. In addition to St Peter's, the Darlinghurst valley was served by the Edmund Blacket-designed Presbyterian church on the corner of Stanley and Palmer streets from 1856, a Baptist Tabernacle in Burton Street and a Methodist church in Dowling Street. The Baptist Tabernacle was purchased by the City of Sydney in 2003 and renovated for reuse, while the Presbyterian church has been converted for use as offices and living space.

Working in Darlinghurst

Since European settlement most land in Darlinghurst has been used for housing. Most residents worked in the city or the docks around Woolloomooloo Bay, or in the shops and pubs that served them. There were however a number of small industrial sites, factories and workshops from the earliest period of development. A couple of these were unusual in Sydney at the time.

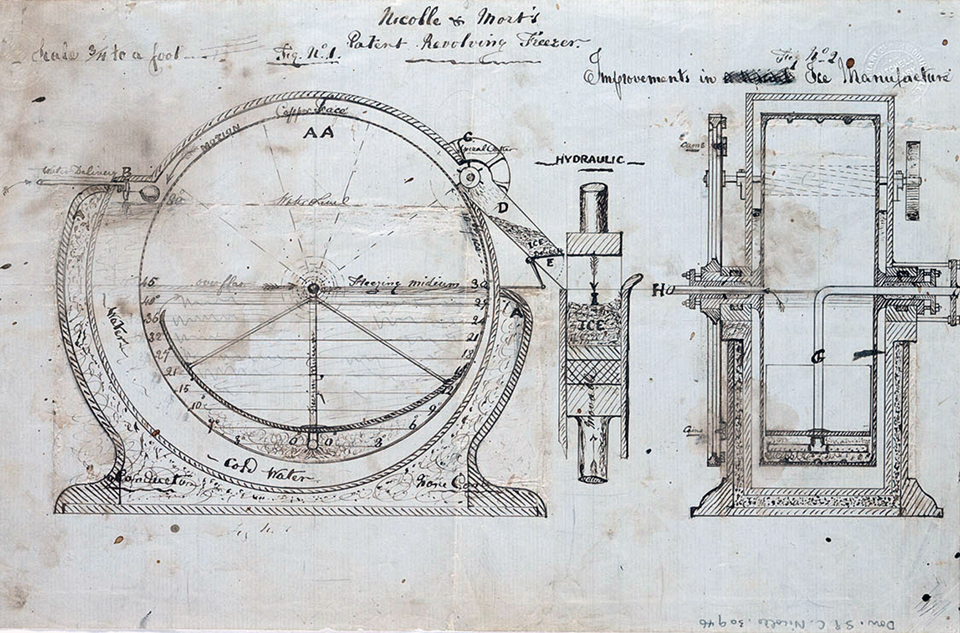

In 1860 a Frenchman, Eugene Dominique Nicolle, advertised in the Sydney Morning Herald the opening of the Sydney Ice Company in Darlinghurst. Nicolle was using a technique already in use in Victoria to make artificial ice for the first time in Sydney. [media]He went on to improve the process, through the use of ammonia rather than ether, and became one of the first people in the world to sell artificial ice on a successful, commercial basis. Nicolle later joined with Thomas Mort to pioneer refrigeration for meat export. His small factory was located in what is now Ice Street. [20]

In 1867 Richard Redgate was operating a Steam Coffee and Spice Mill in Francis Street, which was still there in 1887, perhaps an early indication of Darlinghurst's love affair with coffee. Close by in Charlotte Lane more traditional industries operated, including a foundry and timber yard. In Burnell Street were James Tuffy's cow yards and in Smedley Street stood the William Street Dairy, boasting a large yard and 8 stalls. By 1887 steam laundries occupied long frontages in Palmer Street and Yurong Street. Palmer Street also had a number of stables and associated yards, as well as an Aerated Water Factory.

Pubs were to be found on most street corners. In 1887 there were 22 hotels in the suburb, the vast majority of these being in the valley between Bourke and Yurong streets. Shops soon spread along Oxford and William streets, often with dwellings above. All of these were swept away on the northern side of Oxford Street from 1909 and the southern side of William Street from 1916 when the City Council widened these thoroughfares to make room for increasing traffic flows to and from the city. [21]

In 1904 a macaroni factory had opened in Stanley Street. Run by Luciano and Carolina Rizzo, it was the first pasta factory in Sydney and the first Italian business in Stanley Street. The factory remained in Stanley Street until the late 1930s when it was listed as being run by Luciano's second wife Maria as an Italian warehouse and importer. By this time the street had become the hub of a vibrant Italian and Mediterranean community. [22]

Small-scale industrial sites and medium-sized factories remained scattered around the area into the 1980s and 1990s. Factories such as Lustre Hosiery (Burton Street), Sargent's Pies (corner Burton and Bourke streets), National Chemical Products (corner Riley and Liverpool streets), the Australian Record Company (Hargrave Street) and Goodyear Tyre and Rubber (Yurong Street) were some of the larger employers. The Australian Broadcasting Commission also operated out of its studios on the corner of Forbes and William streets.

Another trade long associated with the Darlinghurst area is the sex industry. From the construction of the Victoria Barracks in nearby Paddington in the 1840s and the development of the wharves around Woolloomooloo Bay in the 1860s, brothels and sex workers were attracted to the neighbourhood. [23] While it was always a dangerous industry for those involved, from the early twentieth century a growing criminal element was evident as new laws made it harder for street workers to approach potential clients. By the 1920s, large-scale brothel owners were dominant in Darlinghurst, the most famous madam being Tilly Devine. At the height of her career in the 1930s, Tilly operated approximately 30 bordellos in the Darlinghurst area. [24] Darlinghurst has remained part of the traditional red light district of Sydney, although the area is not as audacious and gaudy as its neighbour Kings Cross.

Residents and reputations

The mix of poor and posh, criminal and respectable, landlord and tenant, families and singles contributed to Darlinghurst's appeal and its chequered reputation. Commentators as early as in the 1840s and 1850s noted the wide mix of classes and building types.

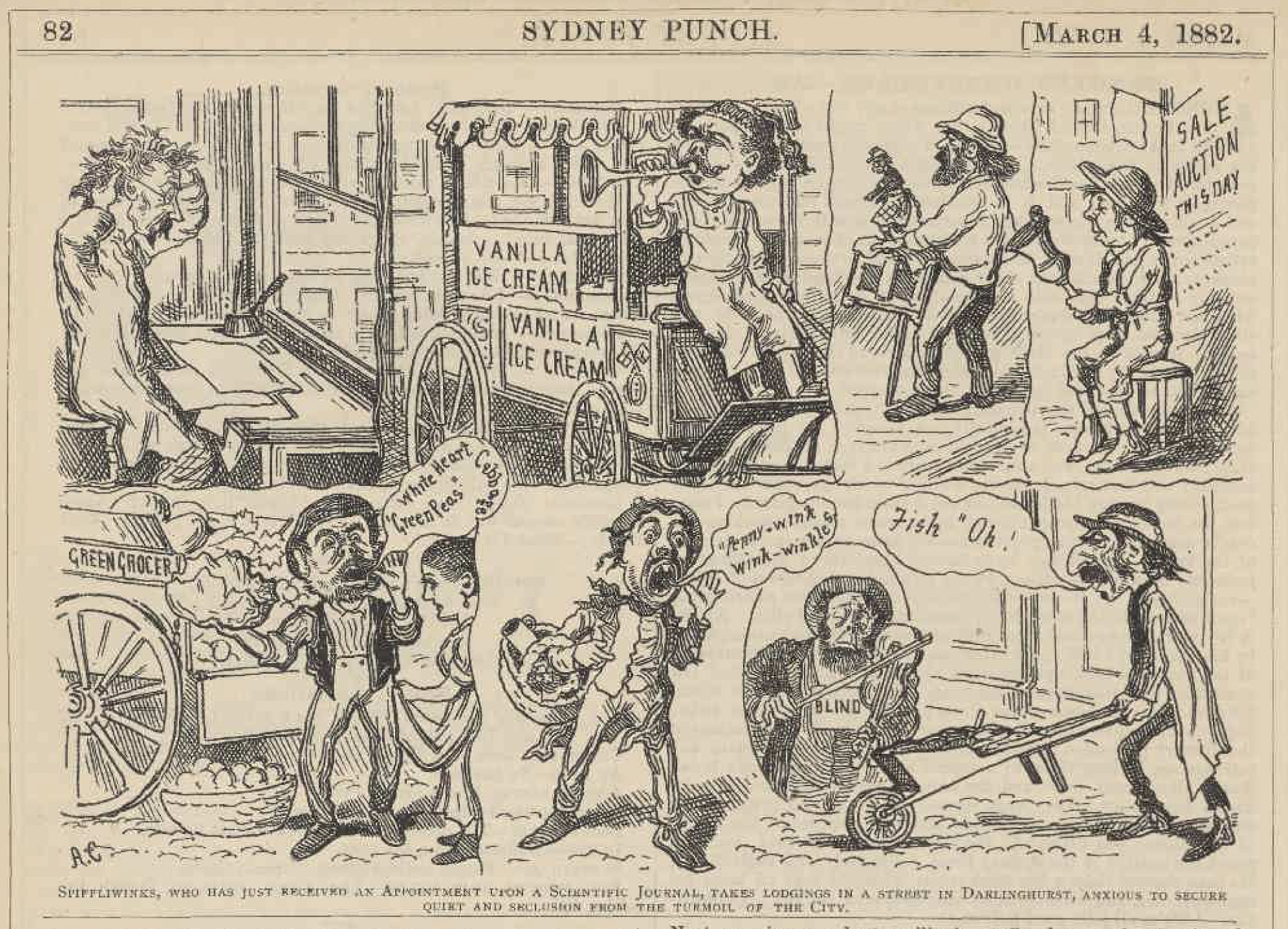

[media]The suburb attracted itinerant workers, single men and poorer families, looking for work on the wharves or in the city. While boarding houses became increasingly common from the 1880s, even as early as 1867 a publicly supported Night Refuge was operating in Francis Street, taking in the poor.

It was not until the 1920s that the reputation of Darlinghurst grew more sinister than that of a regular inner-city neighbourhood. Although the area had experienced the influence of gangs of criminals in the later 1890s through 'the Pushes', during the 1920s a growing criminal element, involved in the sex industry, sly grogging, illegal betting and the drug trade, gave the place a new name in the tabloid press. Their use of straight razors to settle their differences set the new name: Razorhurst. From the period immediately after World War I, through the 1920s and 1930s, Darlinghurst was better known for its gangs and criminal personalities than as a vibrant neighbourhood of families and workers.

The influx of military personnel into the area in World War II and again in the 1960s during the Vietnam War, helped to keep this reputation alive, as brothels and bars, sly grog shops and two-up games all operated to keep the good times flowing. The police station opposite the Court House on Bourke Street was busy, despite its own reputation for involvement in corruption throughout the twentieth century.

By the 1960s there was pressure for development in surrounding areas, but south of William Street this pressure appears not to have been so prevalent. Although a poor area by the 1940s and 1950s, the Darlinghurst neighbourhood attracted the new migrants who flowed into Sydney after World War II. Cheap housing and proximity to the city and the wharves where many found work reinforced communities that had been slowly growing for decades. Stanley Street, where Luciano Rizzo had operated his pasta factory from 1904, became a hub of the Italian and Maltese community, with restaurants and social clubs springing up from the 1950s onwards. [25] Up the road, Sacred Heart Catholic Church held services in Spanish and Portuguese.

The migrant communities brought both stability and a new interest to Darlinghurst. From the 1960s, Darlinghurst and other inner-city suburbs began to attract the bohemians, the artists, the students and young professionals. Terrace houses, once despised, were ideally suited to repair and restoration. The process of gentrification was underway. Around the same period, particularly from the 1970s, the area also became a safer place for Sydney's gay community. The opening of night clubs and bars along Oxford Street in the 1970s and 1980s was preceded by active campaigning and outright confrontation on the streets. On 24 June 1978, gay liberation activists, known as the Gay Solidarity Group (GSG), who had organised a demonstration during the day, followed it up with a parade along Oxford Street to Hyde Park and then back up William Street to the Cross. They were met by the police in force and a riot ensued with 54 arrests. [26] This was the first Mardi Gras, now one of Sydney's biggest festivals, centred on Darlinghurst.

Darlo

Darlinghurst has battled through Sydney's history to become one of its favoured suburbs. A criminal past has been largely forgiven, although it's not altogether forgotten. Galleries and restaurants have replaced the sly grog and SP bookies, but pubs are still close enough to be seen from each others' doorways and brothels remain obvious tenants. New, wealthy residents are moving into trendy new apartment blocks, such as Republic on the site of the old Sargent's pie factory or Seidler's Horizon which looms over the valley. Although rows of terrace houses are still the norm, many of the mean little terraces and back lane hovels of the 1860s are now expensively renovated showpieces. Darlinghurst remains a popular residential suburb, and Sydney's affection for the place is displayed in the very Australian moniker, Darlo.

Notes

[1] 'Old Sydney by Old Chum', Truth, 22 December 1912

[2] F MacDonnell, Before Kings Cross, Nelson, Sydney, 1967, p 10

[3] L Fox, Old Sydney Windmills, Len Fox, Sydney, 1978, p 41

[4] F MacDonnell, Before Kings Cross, Nelson, Sydney, 1967, p 12

[5] L Fox, Old Sydney Windmills, Len Fox, Sydney, 1978, p 54

[6] S Fitzgerald, Sydney 1842–1992, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1992, p 32

[7] Quoted in M Kelly, Faces in the Street: William Street Sydney 1916, DOAK Press, Sydney, 1982, p 7

[8] M Kelly, Faces in the Street: William Street Sydney 1916, DOAK Press, Sydney, 1982, p 8

[9] See Woolcott and Clark's Map of the City of Sydney 1854

[10] 'Old Sydney by Old Chum', Truth, 9 February 1919

[11] WS Jevons, Sydney in 1858: A Social Survey, reprinted in Sydney Morning Herald, 16 November 1929, p 13

[12] WS Jevons, Sydney in 1858: A Social Survey, reprinted in Sydney Morning Herald, 16 November 1929, p 59

[13] C Faro and G Wotherspoon, Street Seen: A History of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000, p 74

[14] EC Rowland, 'Early Schools in NSW', in Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol XXXIII, part V, 1947; J Fletcher and J Burnswoods, Government Schools of NSW 1848–1976, Department of Education, Sydney, 1977

[15] E Butel and T Thompson, Kings Cross Album, Atrand, Sydney, 1984, p 50

[16] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 April, 1858

[17] P Egan, St John's Darlinghurst: Serving the Cross, A short History, 2000, p 117

[18] O'Brien, J, 1952, On Darlinghurst Hill, Ure Smith, Sydney, p 83

[19] City of Sydney Archives, Sacred Heart Resumption Packet, CN 684

[20] F MacDonnell, Before Kings Cross, Nelson, Sydney, 1967, p 95

[21] M Kelly, Faces in the Street: William Street Sydney 1916, DOAK Press, Sydney, 1982, p 5

[22] Sydney Sands Directory 1900–1933

[23] C Faro and G Wotherspoon, Street Seen: A History of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000, pp 84; 102–103

[24] L Writer, Razor: A true story of slashers, gangsters, prostitutes and sly grog, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2001, p 95

[25] C Faro and G Wotherspoon, Street Seen: A History of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000, p 209

[26] C Faro and G Wotherspoon, Street Seen: A History of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000, p 233–236

.