The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Parsley Bay: ‘One of the people’s playgrounds’

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Parsley Bay

[media] Parsley Bay is an inlet of Sydney Harbour bordered by Point Seymour and Village Point, and is the traditional land and waters of the Birrabirragal people.

In 1905 it was described as a:

…beautiful narrow inlet, with low rocky cliffs on each side…with a bottom of pure white sand, which would form an ideal bathing reserve…, one of the finest salt-water bathing spots in Australia, if not the world.[1]

[media]In 1907 the bay and immediate surrounds became a public reserve, and it has remained ‘one of the people’s playgrounds’ ever since’.[2]

First people

Aboriginal people lived around the bay for thousands of years prior to 1788, and continued to live in the area from Rose Bay to Watsons Bay and on the Vaucluse estate throughout the 19th century.[3] Fragments of an ancient twine fishing line, shell deposits of unknown age and rock engravings and hand stencils, many no longer visible, have been found in a number of low shelters bordering the bay, evidence of their long occupation of the land and waters.[4] In the 1890s there was reportedly a ‘camp at the head of the gully in Parsley Bay', members of which would go into Watsons Bay on Sundays to demonstrate spear and boomerang throwing in front of the Greenwich Pier Hotel.[5]

What’s in a name?

[media]The origin of the European name for Parsley Bay is unclear.

The earliest known use of the name Parsley Bay was in February 1793, when Thomas Laycock, Deputy Commissary-General and a quartermaster in the New South Wales Corps, was given a land grant of 80 acres[6] (approximately 33 hectares) '...at the head of Parsley Bay'.[7]

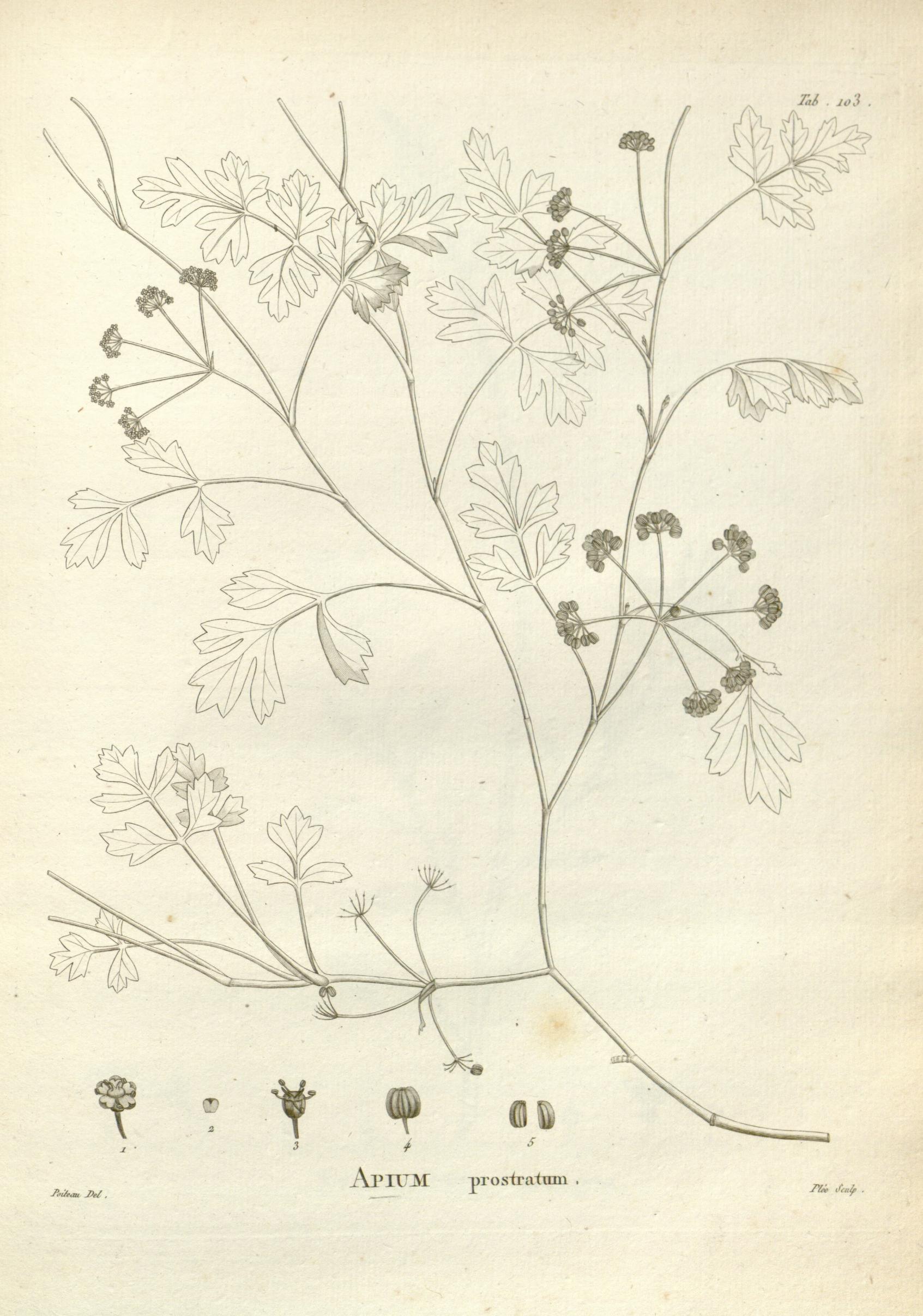

Most sources attribute the European name for the bay to a native plant resembling parsley (probably Apium prostratum)[8] that was eaten by members of the First Fleet.[9] Another claim, made in the 1920s, that the area was named after a man named George Parsley, seems more unlikely, especially when relevant dates are considered. George Parsley (or Pashley) served as a private in the Sydney Loyal Association, a volunteer corps formed in 1800. After this, so the story goes, he allegedly became a fisherman who lived as a hermit and lived in the caves around the bay, but this claim is not supported by the historical evidence.[10]

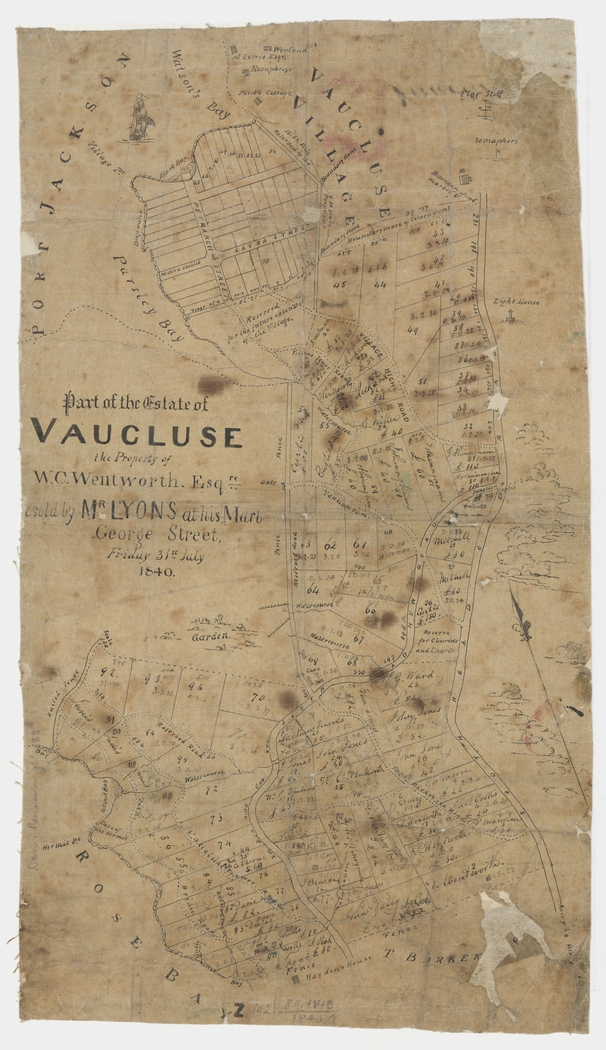

Over time Laycock’s grant was consolidated with other parcels of surrounding land before being purchased by WC Wentworth in 1827,[11] and remaining in private hands for another eighty years.[12]

Harbour Foreshores Vigilance Committee

[media]At the turn of the twentieth century a public movement started to ensure that access to Sydney Harbour and its foreshore did not belong solely to wealthy individual landowners.

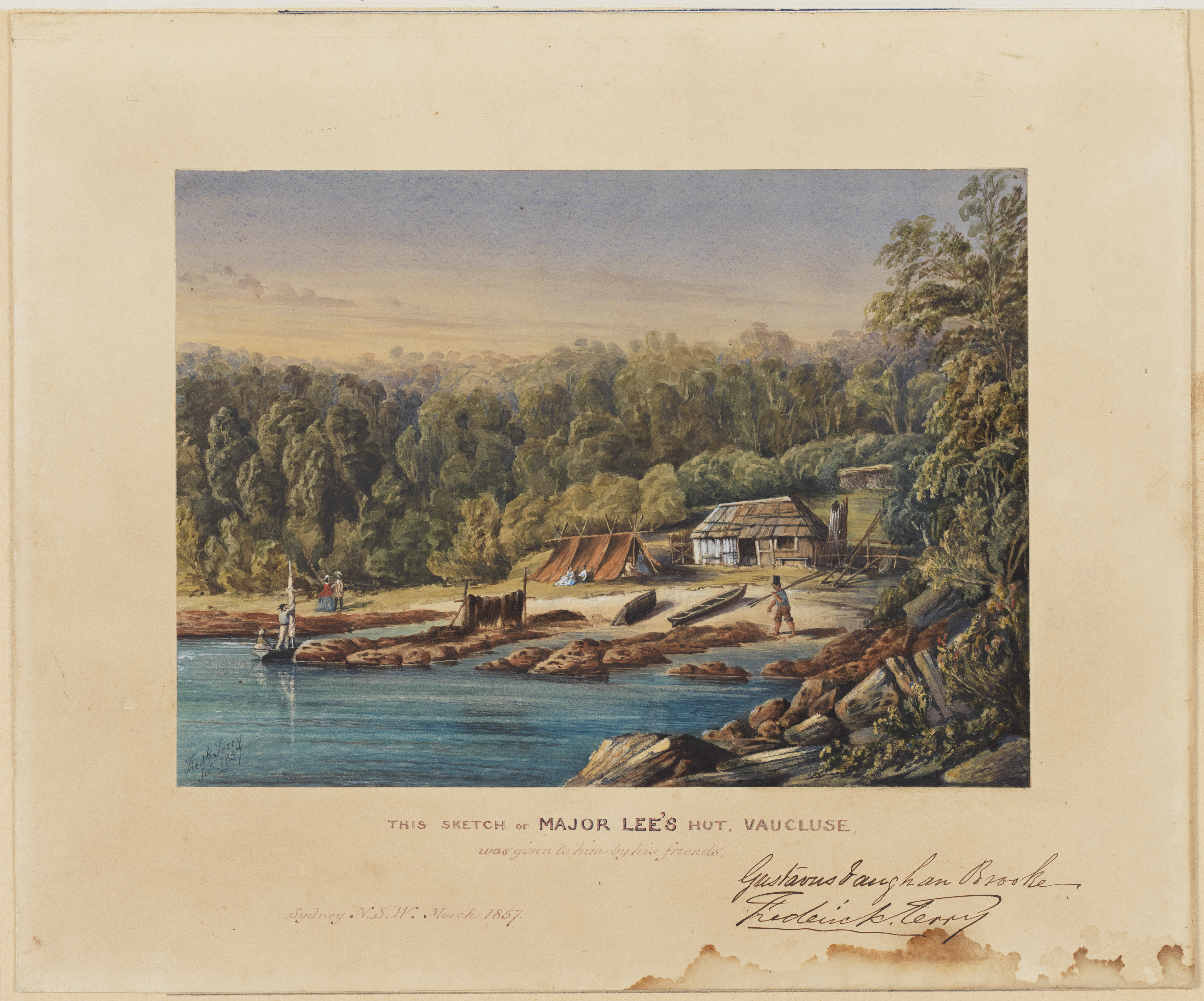

[media]Access to Parsley Bay had always been permitted to the general public, despite it being privately owned. As well as the Aboriginal people living there were fishermen like Major Lee. Locals swam there, and recreational sailors in particular frequently camped there when caught out by weather or nightfall. When the Wentworth estate was subdivided in 1899, a proposal to ‘alienate’ the foreshore saw an alliance form between sailors, swimmers, fishermen and other members of the community who wanted the make sure the bay remained open to all and they asked the government to resume the land.[13]

A key leader in the movement was the Commodore of the Sydney Sailing Club, William Notting, to whom a memorial now stands in Nielsen Park. Notting lobbied strongly for the preservation of Parsley Bay and other foreshore areas,[14] and in 1905 when action had still not been taken, he formed the Harbour Foreshores Vigilance Committee:[15]

It is useless.... to talk about Sydney possessing the most beautiful harbour in the world, unless steps be taken to prevent it becoming a private lake. At present it is little better than a pond in a privately-owned paddock.[16]

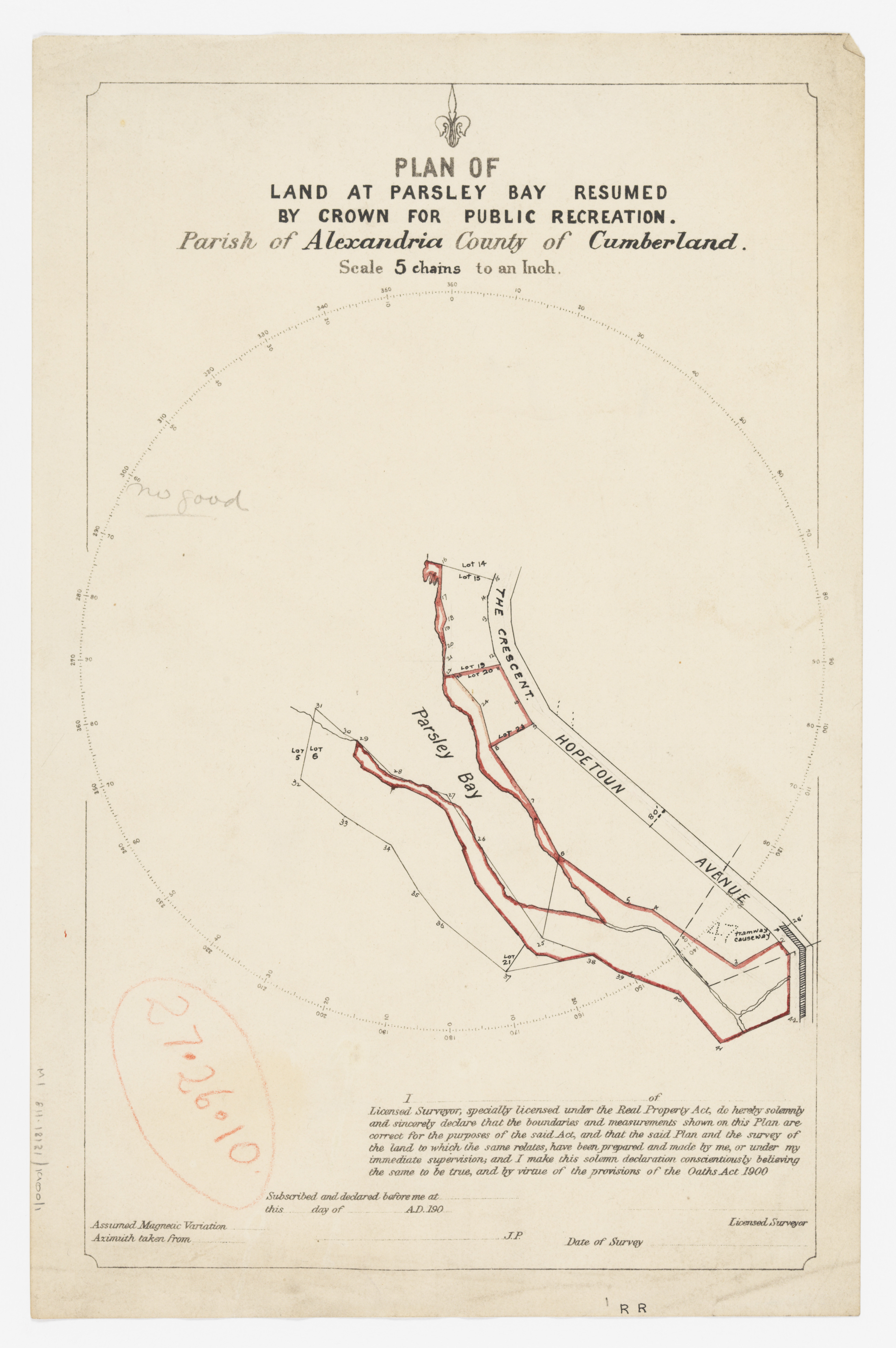

[media]On 29 August 1906, the New South Wales Department of Lands resumed Parsley Bay, and the following year, on 4 December 1907, formally dedicated it to public recreation. Although disappointed by the small amount of land resumed, this was the Harbour Foreshore Vigilance Committee’s first successful campaign.[17]

In 1908 Vaucluse Council accepted responsibility for the reserve and in 1916 was formally appointed the trustee of the land. When Vaucluse was united with the neighbouring municipality of Woollahra in 1948, the reserve came under the control of Woollahra Council.[18]

Parsley Bay Reserve

[media]Always a popular spot with the locals for bathing, Parsley Bay became increasingly popular with visitors from further afield, especially as better public transport developed.

In 1910, a guide for tourists to the area described Parsley Bay as follows:

Parsley Bay, at present the first stopping place of the steamer from Sydney, is a beautiful, sheltered cove. On its shores are ideal camping and picnic grounds, and the large area of bush scenery is perfect, suggesting pleasant rambles to the pleasure seeker. [19]

But it was not always thus. In 1911, Vaucluse Alderman Dr Read described to The Sun his outrage at the 'orgies' taking place on the shores of Parsley Bay:

These shores have been resumed for the people's benefit, forsooth! He had seen of an evening as many as 300 larrikins dancing and yelling like savages, committing indecencies, lighting camp fires, destroying growing timber, cursing and swearing and turning Sabbath into hell.[20]

He responded to 'the brute beasts' via megaphone, and subsequently made a request to the Inspector General of Police for a patrol of the bay on holidays.[21]

In 1910, after concerns about sanitation and the lack of public toilets were raised, the first kiosk at Parsley Bay was constructed, in a style described as similar to a Japanese teahouse. It was designed by the architect Varney Parkes, who had also designed the Vaucluse Town Hall.[22] The refreshment rooms included a residence as the tenant’s duties also included those of caretaker, with some jurisdiction across the park.[23] By 1928 the decision was made to enlarge and rebuild the kiosk, again with a residence attached. Architects Buckle, Carfrae and Turner were commissioned to design the building[24] and it was built by HV Horwood at the entrance to Parsley Bay.

[media]Further works ‘beautifying that popular harbour-side pleasure resort’ were carried out in the early 1930s by Vaucluse Council under the New South Wales government’s unemployment relief scheme. The park was enlarged and improved, and part of the bay reclaimed through the construction of a stone sea wall and dredging to create a picnic area[25]. Dredging the sand deepened the bay below the suspension bridge, but this reduced tidal flushing of the bay and in 2003-4, the Council undertook remediation work on the sea floor to improve the water quality.[26]

Suspension bridge

[media]The benefits of installing a footbridge across 'The Parsley Glen' had been under consideration by Vaucluse Council since 1906. A bridge across the bay would save residents a walk of half a mile (0.8 kilometres) from Neilsen Park to Watsons Bay and provide easier access to the ferries that then called at Point Seymour at the end of Fitzwilliam Road.

In 1910, the construction of a cable suspension bridge was completed at a cost of £500, double the original estimate.[27] The bridge, described as 'a handsome structure' and now classified by the National Trust,[28]is 55 metres long and 2 metres wide with towers, deck and handrails made of wood and cabling and sides made of steel. The work was carried out using council labour and the bridge built to the design of Edwin Stanhope Sautelle, then Town Clerk and Engineer of Vaucluse Council.

[media]Despite the increase in surrounding development, Vaucluse at this time remained a semi-rural area, and in 1917, the Vaucluse Progress Association suggested a turnstile be erected on the Fitzwilliam Road approach to the bridge 'to prevent the danger to pedestrians caused by cattle getting on to the track leading to the Suspension Bridge'.[29]

Japanese visitors

[media]In May 1911, the Japanese Antarctic expedition led by Lieutenant Nobu Shirase sailed into Sydney on the Kainan Maru after being forced to turn back due to the onset of winter. For six months the expedition party camped at Parsley Bay, setting up a prefabricated hut that had been brought with them to serve as their polar headquarters.

[media]The men's camp was a novel curiousity for Sydneysiders, who visited in droves, and they increasingly became part of the Vaucluse community. Local children would spend time and talk to the explorers, teaching them songs and partaking in their everyday activities.

The expedition set sail again in November 1911, having replenished their stores and supplies, and established long term friendships and support of their project. A memorial plaque at Parsley Bay to commemorate the expedition was unveiled by Woollahra Council in 2002, and a playground ship bears the name of the Kainan Maru.

Shark net

[media]Sharks were often seen in Parsley Bay and the surrounding harbour waters, and although the bay’s shallowness made attacks less likely than at other harbour beaches, it was still a reasonable concern.

William Notting had suggested in 1905 that wire shark nets be placed across the bay to makes it safer for swimmers[30] but it wasn’t until September 1930 that Vaucluse Council accepted a tender from the firm Buzacott & Co to supply and install mesh netting at the head of the bay[31]. The net was in place by Christmas Eve 1930, and replaced every three or four years. Sometime after this the Parsley Bay Life Saving Club was formed to further ensure the safety of swimmers[32] but was subsequently disbanded.

A floating net was installed by Woollahra Council in 1982, which is removed each winter for cleaning and repair.

'A more charming playground it would be difficult to find'

[media]In 1907 the Daily Telegraph paid Parsley Bay a visit, commending Notting’s vision of a publicly available foreshore and recommending an extension of the reserve:

…it is now the playground of many hundreds of men, women, and children, and a more charming playground it would be difficult to find. …The scene was a peculiarly Australian one. While parents or others of the family parties spread the table cloths, and boiled the billy or obtained hot water from the neighboring refreshment rooms the youngsters - and sometimes oldsters, too - disported themselves in the smooth waters of the bay, which was completely sheltered from a rather stiff north-east breeze. Those who were not bathing found ample space for rounders and other games…[33]

Thanks to the forethought and action of Harbour Foreshores Vigilance Committee, the bay remains a popular place for gatherings of famillies and friends to enjoy.

Further Reading

Jane Britten and Caroline Yeh, Parsley Bay: Place of the Heart, Double Bay, NSW: Woollahra Municipal Council, 2000

Robin Derricourt, South Head Sydney and the Origins of Watsons Bay, Sydney: Watsons Bay Association, 2011

Harbour Foreshore at Vaucluse, Woolahra Municipal Council, , http://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/library/local_history/local_areas/harbour_foreshores_at_vaucluse, viewed 21 January 2019

Parsley Bay Reserve History, Woollahra Library Local History Centre, June 2005, https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/16272/Parsley_Bay_Reserve_Web.pdf, viewed 21 January 2019

Notes

[1] To the Editor of the Herald, Sydney Morning Herald, 11 October 1905, p4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/1326522

[2] PARSLEY BAY: One of the People’s Playgrounds, The Daily Telegraph, 27 December, 1907, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238256569

[3] Paul Irish, Hidden in Plain View: The Aboriginal People of Coastal Sydney, Sydney: NewSouth Publishing, 2017

[4] Robin Derricourt, South Head Sydney and the Origins of Watsons Bay, Sydney: Watsons Bay Association, 2011, p 34-35; Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records, Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010, p96

[5] W.F. Brown, Many memories of Watsons Bay, Wentworth Courier, 29 October 1986, p13 & p104, quoted in Robin Derricourt, South Head Sydney and the Origins of Watsons Bay, Sydney: Watsons Bay Association, 2011, p105

[6] Ryan RJ, Land grants, 1788-1809, Sydney: Australian Documents Library, 1981, p13; , 'Laycock, Thomas (1756-1809)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/laycock-thomas-2339 viewed, 8 May 2019

[7] Parsley Bay Reserve History, Woollahra Library Local History Centre, June 2005, https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/16272/Parsley_Bay_Reserve_Web.pdf, viewed 6 April 2019

[8] Tim Low, Foods of the First Fleet: Convict Foodplants of Old Sydney Town, Australian Natural History, Summer 1987-88, Vol 22, No 7, p295, https://media.australianmuseum.net.au/media/dd/Uploads/Documents/38627/ams370_vXXII_07_LowRes.eaab05e.pdf

[9] Parsley Bay, Evening News, 18 July 1896, p 9 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/111043689

[10] It seems possible that George Parsley’s name was conflated with the name of another hermit and fisherman, Major Lee, who lived in Parsley Bay in the 19th century, and that this may have led to this ‘urban myth’. Major Lee was a well known cave-dwelling hermit in Parlsey Bay who died in the 1880s. The version of the story citing George Parsley as the inspiration behind the bay’s name seems to have been first published in 1929 by the Royal Australian Historical Society, but by 1932 another RAHS researcher had found no evidence of either claim. Parsley, the member of the Sydney Loyal Volunteers was also known as George Pashley, and was in fact a tailor living in the Rocks; Colonial Secretary Index, 1788-1825: Pashley-Paterson, State Archives and Records NSW http://colsec.records.nsw.gov.au/p/F43c_pa-13.htm, viewed 22 May 2020; OLD SYDNEY, and its Harbour and Bays, Illustrated Sydney News, 4 April 1889, p12 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63621599; Royal Australian Historical Society, Annual report and statement of accounts, Vol 15, Part 7 (1930), Twenty-Ninth Annual Report for 1929, Appendix 1, Answers to questions by the Honorary Research Secretary, p401 http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-596677684; Looking Back, The Daily Telegraph, 2 June 1931, p11 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article246248930; James Jervis, Origin of the Names in Port Jackson, Journal and Proceedings, Royal Australian History Association, vol 31, Part 6 1945, p390 http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-603260354

[11] Samuel Breakwell papers concerning Vaucluse estate, 1803–1838, 1898, 1918. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (MLMSS 1720), http://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110320275, viewed 9 June 2017

[12] Edward Higginbotham, Archaeological Investigation of the Outbuildings at Vaucluse House, Vaucluse, NSW: NSW Archeology Online, 1990, http://nswaol.library.usyd.edu.au/view?docId=pdfs/13167_ID_Higginbotham1990VaucluseHouseOutbldingsExcavRpt.pdf, viewed 9 June 2017

[13] ALIENATION OF WATER FRONTAGES, The Daily Telegraph, 25 October 1899, p7 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article237199512; OUR BEAUTIFUL HARBOR, The Daily Telegraph, 25 October 1899, p4, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article237192023

[14] PARSLEY BAY, Evening News, 25 April 1900, p. 8. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article113717235

[15] Harbour Foreshores–Vigilance Committee Formed, Sydney Morning Herald, 2 November 1905, p 5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/14749751

[16] SYDNEY HARBOR, Evening News ,19 October, 1907, p. 10 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article113900675

[17] Harbour Foreshore at Vaucluse, Woolahra Municipal Council, http://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/library/local_history/local_areas/harbour_foreshores_at_vaucluse, viewed 10 April 2017

[18] Parsley Bay Reserve History, Woollahra Library Local History Centre, June 2005, https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/16272/Parsley_Bay_Reserve_Web.pdf, viewed 6 April 2018

[19] Tourists' Guide to Watsons Bay and Vaucluse, 1910, cited in The Harbour Foreshores at Vaucluse, Woollahra Municipal Council, https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/library/explore_our_collection/local_history/local_areas/harbour_foreshores_at_vaucluse viewed 8 May 2019

[20] Sabbath a Hell: Larrikins at Parsley Bay. An Alderman describes the “orgies, The Sun, 12 September 1911, p 3. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/221547425, viewed 6 April 2018; THROUGH A SPY-GLASS, The Sun, 17 October 1912, p12, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article228846543, vewed June 5, 2020

[21] Larrikins at Parsley Bay, Evening News, 11 January 1912, p2 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/113811316, viewed 6 April 2018

[22] Parsley Bay Reserve History, Woollahra Library Local History Centre, June 2005, https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/16272/Parsley_Bay_Reserve_Web.pdf, viewed 21 January 2019

[23] Preserving Order, The Sunday Sun, 28 August 1910, p 9 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/226887365; 'Parsley Bay Resort', The Sun, 9 May 1911, p 3 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/221584423

[24] Opportunity Report, Construction and Local Government Journal, 11 July 1928, p16 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/109728797

[25] PARSLEY BAY, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 December 1933, p8 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17036142; PREVENTION AND RELIEF OF UNEMPLOYMENT ACT, 1930-1931 Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales, 13 December 1932, p 4401 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article219912519; PREVENTION AND RELIEF OF UNEMPLOYMENT ACT, 1930-1932, Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales, 18 August 1933, p3087 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article219977201

[26] Parsley Bay Swimming Enclosure, Woollahra Municipal Council, website https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/recreation/parks,_reserves_and_playgrounds/list_of_parks_and_playgrounds/parks_and_playgrounds/parsley_bay_swimming_enclosure viewed 20 May 2020

[27] Parsley Bay Suspension Bridge, The Sun, Friday 2 December 1910, p2 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/229973940; PROPOSED SUSPENSION BRIDGE, The Australian Star, 11 February 1909, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article229391849

[28] J Barnes, C Rizos, H-K Lee, 'The Integration of GPS and Pseudolites for Bridge Monitoring' in A Window on the Future of Geodesy: Proceedings of the International Association of Geodesy, edited by Fernando Sanso, Berlin, Germany: Springer, 30 March 2006, p 87

[29] Jane Britten and Caroline Yeh, 'VMC 27.7.1917 sheet no 49', in Parsley Bay: Place of the Heart, Double Bay, NSW: Woollahra Municipal Council, 2000, p 23

[30] Voice of the People, Evening News, 9 November 1905, p 7 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/113283289

[31] Parsley Bay Reserve History, June 2005, Woollahra Library Local History Centre, https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/16272/Parsley_Bay_Reserve_Web.pdf, viewed 6 April 2018; CONSTRUCTION OF SHARK-PROOF NET AT PARSLEY BAY, Sydney Morning Herald, 24 December 1930, p.12 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16741192

[32] LIFESAVING CARNIVAL, Lithgow Mercury (TOWN EDITION), 26 January 1940, p. 6 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article220787452

[33] PARSLEY BAY: One of the People’s Playgrounds, The Daily Telegraph, 27 December, 1907, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238256569