The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Sydney Harbour: A Cultural Landscape

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Sydney Harbour: A cultural landscape

[media]For as long as it has existed – some 6,000 years – Sydney Harbour has been a source of inspiration. The harbour's first people carved images of the animals they saw and hunted. With the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, European representation of the harbour's landscape, plants, people and animals began. Numerous artists and writers since have followed in their footsteps.

Though much admired for its beauty, there was less artistic and literary interest in the harbour's boatbuilders, wharf workers, sailors and fishers. The colony, then the nation, was defined by the flocks and forests and people of the inland. It was only after the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge that, from 1932, the waterway represented Australia. The harbour's iconic status was confirmed with the completion of the Sydney Opera House in 1973, the tourist boom that followed and the Bicentenary of 1988.

As the city surrounding the water has developed and changed, so too has the harbour. Though it may not have been apparent in 1957, the Opera House was a harbinger of a new waterway, one that was soon to be emptied of tankers and cargo ships, filled with weekend yachters and sightseers and lined with expensive real estate.

When Darling Harbour was transformed as part of the Bicentenary celebration, working structures there were simply erased. While this represented a complete transformation of a working waterfront, there was some appreciation of redundant working structures and the beginning of adaptive reuse. The finger wharves at Walsh Bay and the foreshore of Circular Quay are now home to a host of world-class dance, theatre and other cultural institutions.

Sydney's relationship with development continues to be complex and, at times, dramatic. Direct action preserved the colonial-era precinct called The Rocks while Darling Harbour was completely cleared to create a complex of exhibition buildings, shops, restaurants and public spaces. With the controversial redevelopment of Barangaroo into exclusive apartments and a casino imminent, the transformation from working harbour to postindustrial waterway continues.

First people of the harbour

People lived on the south-eastern edge of Australia well before the sea started rising around 11,000 ago. Humans witnessed the inundation, albeit over generations, and adapted to the changing environments. Ultimately, they retreated to occupy the foreshores that were created when the waters finally stopped rising some 6,000 years ago. By then what had been a river valley was a complex harbour of many coves, headlands and points, with three estuarine arms to the immediate north, north-west and west.

At some time before or after the water stabilized, these people established territories around the waterway based upon family groups. By the 1700s, there were at least eight clans occupying specific parts of the harbour foreshores. These were 'saltwater people' who gathered much of their food from the waterway and for whom the meaning of place was all-important. The land, shore, and probably the harbour itself, were imbued with social and spiritual significance. Headlands, points and coves were named from Boree (North Head) along to Parramatta, at the end of the Harbour's western estuary, and back around to Tar-ral-be (South Head).

These people came to know their landscape intimately, making use of much of what the forest, foreshore and waterway provided: bark for canoes and fishing line, shell for hooks, plant resin for adhesive, grass or fibrous leaf for baskets. The local sandstone was too brittle for axe heads so hard rock was traded from further away. However, sandstone was ideal for engraving, so on rock platforms along the waterway, the harbour's first people carved images of the animals they saw and hunted and to which they may have attached totemic significance.

Often these rock platforms had vistas up and down the harbour. One engraving, on a north-side headland in Gammeraygal country, showed a whale or large fish with a human figure inside. A group of others to the east in Gayamaygal country showed fish, sharks and what might have been a fairy penguin. There was another group of images on a peninsular low to the water on the opposite shore, a place the Gadigal people called Willara. There were many others. [1]

There were ceremonies too. One, to mark the transition of boys to manhood, occurred at a cove called Woggan-ma-gule in February 1795. An oval shaped space referred to as a Yoo-lahng was prepared in which there was dancing for a week before the initiation. It was Gadigal land but men gathered from clans along the harbour and to the west. They were painted in the custom of their country so that body art was combined with performance. The naval officer David Collins attended throughout and described the event and some of those who participated in the event:

…one man [was] painted white to the middle... Others were distinguished by large white circles around the eyes... all [were] armed with clubs, spears and throwing sticks.

The men who presided over the initiation confronted the boys:

…with a song or rather a shout peculiar to this occasion, clattering their shields and spears, and raising a dust with their feet that nearly obscured the objects around them. [2]

European presence

The cultural business that David Collins witnessed survived despite seven years of European presence – an intrusion that brought with it disease and dispossession. Remarkably, culture continued so that in the 1820s, when traditional social groupings had been profoundly realigned, a visiting Russian scientist called IM Siminov could describe the body art and performance practised – routinely it seems – by the band that had formed around the charismatic man Bungaree at Kirribilli. There, on one evening, faces were painted red with ochre and music was made using two small sticks and the human voice. Dancers 'jumped at each blow of the sticks, and hummed....'. [3]

That had been Gamaraygal land before the arrival of the British. Bungaree's traditional country was farther north along another waterway called Broken Bay by the newcomers. The dislocation dissolved old boundaries and facilitated travel for Aboriginal people – far more than would have been traditionally undertaken. So much so that Bungaree came to Sydney and sailed around the continent on a British survey vessel, the Investigator. In the 1820s, he came to regard all the land north of the harbour as his country.

By then successive British governors had given away, or sold, most of the Gamaraygal foreshores – not that all the new owners cared to reside on land that was hard to farm and separated from the town by water. Rather, most of the development was occurring on the southern shore where the authorities were trying to balance an appetite for commerce among a growing free population with the needs of administering the convict colony established in 1788 – while retaining land for the Crown.

Farm Cove

Early on, the old Aboriginal ceremonial ground at Woggan-ma-gule was planted out in an attempt to grow food and the newcomers called it Farm Cove. By the 1830s, the site was a scientific institution established to assess the acclimatisation of botanical species to the colony. It was, in this sense, a crucible for the widespread transformation of ecologies far beyond the harbour's shores. Productive plants, including fruit trees, olives and grapes, were nurtured along with ornamental varieties, such as gardenias and fuchsias, introduced to turn domestic gardens into landscapes of familiarity and repose for the new people.

The Botanic Garden and Governor's Domain

Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who most wanted to make respectable citizens out of convict stock, also desired to keep apart from the people he ruled. It was Macquarie who built a wall around the land surrounding the 'Botanic Garden' so as to create a Governor's Domain in 1813 – a place of 'seclusion from the public gaze'. [4] However, after the end of convict transportation in 1840s, and with the development of a complex society in which aspiration and strengthening democracy were a feature, both the formally named Botanic Garden and the Domain became public parks for the recreation and uplift of the population. While the former space was always regulated and policed, the Domain came to host political expression, massed assembly and games. It went from being an exclusive space to a people's park, a place characterised as much by its users as its managers.

Harbour villas

Macquarie and his wife Elizabeth were intensely interested in design. The Governor commissioned a new house and stables to be built in his Domain in the Gothic style. Completed in 1821, the castle-like stables joined a castellated foreshore fort at Bennelong Point – both designed by the convict architect Francis Greenway – so that most important part of the harbour evoked a British, rather than continental, landscape. Gothic came to eclipse the classically-inspired forms of earlier Georgian-era structures. Macquarie's choice anticipated the rise of Gothic style in Britain where it was championed by AW Pugin and John Ruskin. The matching Government House was not built in Lachlan's time. Rather it waited until the Gothic revival was well underway and was the work of the English architect Edward Blore who never visited the site of his commission. [5]

Stone villas with high-pitched rooflines, like Lindsey at Darling Point and the dwelling that became known as Kirribilli House, were a feature of the mid-nineteenth century harbour foreshores. Not all, or even most, were designed by architects for by then pattern books were available for aspiring clients to pore over and decide upon style. Conrad Martens, an English artist who sailed with Charles Darwin on HMS Beagle and who decided to settle on the waterway after he arrived in 1836, painted several harbour villas. He too built a Gothic villa of Sydney sandstone called Rockleigh Grange, on the north shore, which provided a vantage for so many of his views.

Painting the harbour

From the time the unnamed 'Port Jackson Painter' disembarked from a convict transport in 1788 and started depicting the landscape in a series of unsigned watercolours, the harbour has been documented and celebrated in pencil, paint and ink by dozens of artists.

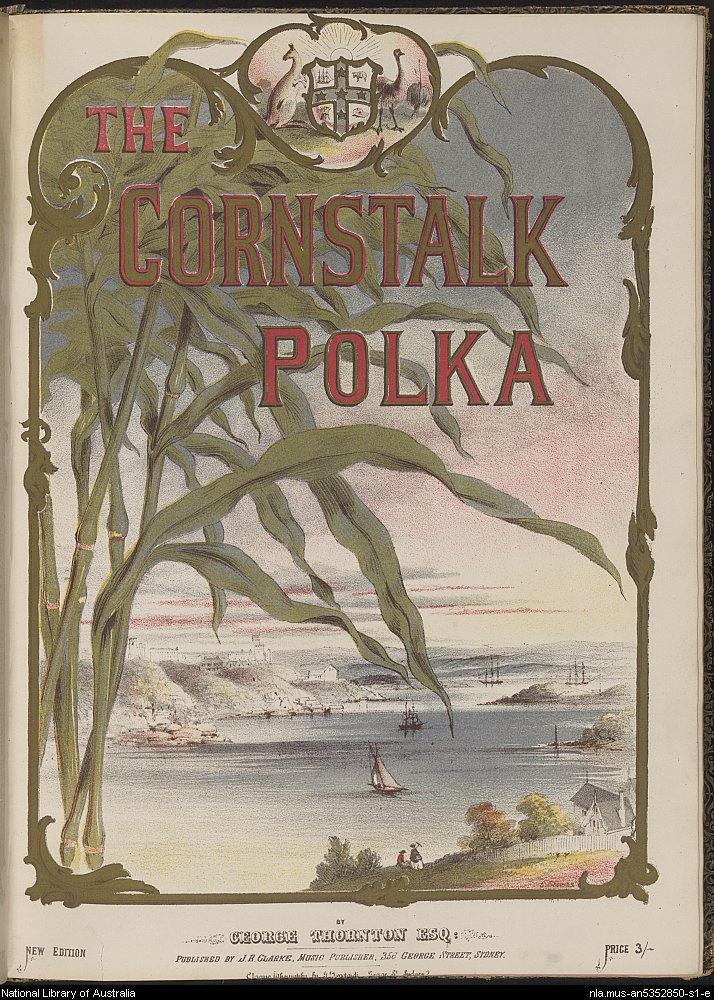

In the mid-nineteenth century, Conrad Martens was joined by Edward Peacock, who preferred to work in oils, and Frederick Garling, who celebrated the growing maritime trade with his ship portraits. ST Gill and John Skinner Prout made the most of new technologies to market their harbour artworks as prints. Near the century's end, an artists' camp was set up in a small north shore cove named Little Sirius after one of the First Fleet vessels. From there Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton soaked up the Harbour's beauty and painted many more views of the waterway. [6]

By then Sydney Harbour was known across the world as a place of great beauty. Overseas writers such as Anthony Trollope and Mark Twain visited, describing the place in travelogues. Few authors, however, sought to set stories there or to explore the lives of harbour people; EJ Brady and Henry Lawson being the exceptions who proved the rule.

Australia's wealth was being made inland and that was where the drama of nation building was imagined and, therefore, that was where an Australian national identity was created. Though much admired, Sydney Harbour – with its boatbuilders, wharf workers, sailors and fishers – hardly represented the greater whole. Instead New South Wales, and then Australia, was known as a land of sheep and wheat, forests and mines.

A working harbour

Irrelevant though they may have been to most artists and writers through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the people who worked along the harbour's foreshores were intrinsic to the culture and commerce of the place. Boatbuilders were designing and constructing seagoing vessels in Sydney Cove within 20 years of the colony's foundation. The first steam powered vessel to be seen in colonial waters was slipped into Neutral Bay in 1831. Local shipwrights competed successfully with competition from abroad – including the great shipyards on the Clyde.

When Sydney Cove became Circular Quay in the mid-1800s, and was given over to the arrival and departure of people and goods, maritime construction moved to the coves of the west and the sparsely settled north shore. English-born engineer, Norman Selfe, learned his profession in the great workshops of Darling Harbour. In the 1870s he designed the first double-ended ferry to better serve the increasing passenger traffic on the waterway. The proudly named Wallaby, which could leave a jetty without turning around, was launched in quiet Berrys Bay on the north side in 1879.

By contrast, all was bustle on the south side. The shoreline from the quay to Pyrmont was crowded with wharves and jetties. There the wealth of the interior – wool, wheat and meat –left, and manufactured goods arrived from Britain, Europe and the United States. Behind the docks, people lived packed into homes that were often small and dirty. It was there that plague broke out in 1901. The official reaction included a rationalisation of harbour management through the creation of the Sydney Harbour Trust and the demolition of the old docks. New finger wharves were built, and concrete walls constructed, to confound the rats that arrived with the overseas shipping. The man in charge was Henry Deane Walsh and his name lives on in the bay that was most transformed by his public works.

The waterway was filled with vessels: liners and cargo ships from overseas, steamers bringing and taking people and goods to and from the small ports strung along the coast. There were local schooners and skiffs and the fleet of ferries that serviced the harbour. These last watercraft were the means by which the northern and southern shores were connected before the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The traffic was so regular and essential that, in the early 1920s, the visiting author DH Lawrence wrote of 'huge restless, modern Sydney whose million inhabitants seem to slip like fishes from one side of the harbour to the other'. [7] The Sydney writer Kenneth Slessor later described the traffic and the myriad of coves they serviced by ferries and skiffs as giving rise to 'a dispersed and vaguer kind of Venice'. [8]

Modern Sydney

[media]As Lawrence was writing, 'modern Sydney' was starting to plan for the construction of the greatest symbol of modernity then undertaken in the country. The Sydney Harbour Bridge Act was passed in 1922 and the arch itself completed a decade later. Though it serviced a city, the bridge also embodied national achievement. It was a sublime monolith whose engineered ingenuity was apparent for all to see in the massive girders and rivets that comprised the arch. For decorative effect, two giant granite pylons stood at each approach to the bridge, like gateways connecting a city previously divided by water. They had no structural purpose but served to add extra gravitas and classical dignity to the mass. The bridge gave the harbour an iconic structure like no other and in doing so helped to 'brand' the waterway as a place that stood for Australia.

Sydney Harbour Bridge

Artists found the structure irresistible; among others, Jessie Traill and Robert Emerson Curtis rendered it in pencil and print. The assembly of shapes and surfaces that comprised the bridge inspired modernists like Roland Wakelin and Grace Cossington Smith who relished drawing the structure in planes of colour. The pictorialist photographer Harold Cazneaux juxtaposed its curves with those of an obsolete sailing vessel, emphasizing the old and the new. Another master of the camera, Henri Mallard, climbed hundreds of metres into the air to document the workers who put the bridge together in heroic [media]poses spontaneously struck among the girders.

Mallard's images paralleled Lewis Hine's extraordinary Empire State Building photographs and anticipated the artistic interest in working people and their labour that led to the formation of the politically radical Contemporary Art Society in 1938. In the following decades, Roy Dalgarno, Herbert Badham and the sculptor Lyndon Dadswell represented harbour workers, so long neglected by artists. The latter executed a frieze in granite in 1948–49 showing waterside workers heaving crates and bales of wool in Circular Quay. The scene was historical but the men appeared so stylised in appearance that they might have been contemporary.

Dadswell's relief was commissioned for the entrance to the new Maritime Services Building completed on the west side of Sydney Cove in 1952. That building, made with Sydney sandstone, echoed the monumentalism of the bridge that stood behind it with its stepped classical facade. Delayed by war, the building's design was old-fashioned almost as soon as it was finished. Within a few years, on the eastern side of the cove, steel and glass office blocks were replacing nineteenth century stone warehouses. The country's tallest skyscraper, the AMP building, was built on the site of a once glorious and ornate wool store from 1961–62. International style modernism was transforming Sydney and many people approved of the change.

Sydney Opera House

[media]Along from the new offices, on Bennelong Point where Macquarie's fort once stood, a Danish architect named Jorn Utzon imagined another type of modernism. The extraordinary sailed structure he sketched won the competition for city's new opera house in 1957. After it was opened in 1973, the Sydney Opera House sat in equilibrium with the Sydney Harbour Bridge – the latter was an obvious piece of brilliant engineering while the Opera House was a work of art as much as architecture. Together they became of the symbols of Sydney Harbour and, by the tourist boom of the 1980s, Australia itself.

Revitalising the foreshore

By then the working/industrial harbour of the nineteenth and early twentieth century was on the wane as the city that surrounded the water was given over to finance, retail, services, high-end residential developments and cultural pursuits. Though it may not have been apparent to many when it was conceived, the Opera House had been harbinger of a new harbour that would be emptied of tankers and cargo ships and filled instead with weekend yachters and sightseers, and lined by real estate, the value of which just kept rising. The social dynamics of that brash new city, where proximity to the harbour was equated with social status, were so familiar by the mid-1980s that they were ripe for satire in David Williamson's play, Emerald City, which premiered (appropriately enough) in the Sydney Opera House in 1987.

In the intervening decades, Sydney's relationship with modernism and development became complex and sometimes dramatic. The impulse to replace all that was old with the new was rejected in the colonial-era precinct called The Rocks. There were protests and the heritage movement shifted from polite advocacy to direct action. Across in Darling Harbour, the working waterfront was completely cleared to create a postindustrial postmodern complex of exhibition buildings, shops, restaurants and public spaces.

The Darling Harbour precinct was ready as a showpiece for the 1988 Bicentenary – Australia's celebration of its British foundation. The harbour became the focal point of an extraordinary international celebration. Tall ships entered the waterway from countries near and far and an audience of nearly two million people crowded the foreshores to witness it. As a concession to the newly acknowledged Aboriginal people, there was no triumphalist re-enactment of Phillip's landing, as had occurred in at the 1938 Sesquicentenary of colonisation. However, on some of the foreshores, Aboriginal people still enacted protests at what they named Invasion Day./place/walsh_bay_0

While Darling Harbour represented a complete transformation of a working waterfront, there was some appreciation of redundant working structures. The Sydney Theatre Company (STC), established in 1979, saw the potential of Henry Deane Walsh's now obsolete finger wharves. In 1983, the same Labor Government which championed Darling Harbour, funded the adaptation of Wharf 4. Sydney Dance Company and Bangarra – the Aboriginal dance theatre company established in 1989 – joined the STC in Pier 4/5. The new Sydney Theatre was built in 2000 behind the wharves where the bond stores stood. Walsh Bay itself became a case study in adaptive reuse and, by 2012, was a vibrant precinct of residential accommodation, restaurants, and cultural organisations.

The same ideal underpinned the revitalisation of the old Maritime Services Board Building, rendered obsolete in 1987 when its first tenant, rather symbolically, abandoned its waterfront site for an office tower. That structure reopened as the Museum of Contemporary Art in 1991. [9] Similarly, Customs House, enlarged three times since it was built at the head of the cove in 1840s to administer the arrival of goods and people, outlived its original purpose and was redesigned internally twice between 1994 and 2004 to accommodate cafes, cultural spaces and the Sydney City Library.

Walsh Bay remains special largely because of the retention of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century architecture and access to the waterfront around the finger wharves. There is an organic feel that the sparkling white Darling Harbour simply does not possess. As the transition from working harbour to postindustrial waterway continues, other waterfronts have become available for redevelopment. The most recent is at east Darling Harbour, opposite and along from the waterfront developed in the 1980s and 1990s. That foreshore was called Barrangaroo after the notable Gameraygal woman who lived through the first years of colonisation and made enough of an impression to be noted in the colonial journals.

Here there is no infrastructure to retain and guide the aesthetics of the new development – for all that was lost when the place was turned over to shipping containers and a long concrete wharf in the early 1970s. A clean slate for architects, planners, politicians and developers, its design has been dogged by controversy about the extent of political process, public access, privatisation of waterfront and the size and appearance of the buildings. Few in Sydney confidently expect another masterpiece like the Opera House to be built and many fear the alienation and despoliation of valuable harbour front land by exclusive apartments and a casino.

There will be other controversies when the nearby White Bay and Glebe Island waterfronts are finally redeveloped. The passion with which each site is changed underlines the significance with which the harbour is now held as an iconic place – as an aquatic common.

References

Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Historical Records, second edition, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 2010

David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, with Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, etc. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol 1, 1798, edited by Brian Fletcher, AH and AW Reed in association with Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1975

Ian Hoskins, Sydney Harbour: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2009, pp 159–162

Lachlan Macquarie quoted in Lionel Gilbert, The Royal Botanic Gardens: A History 1816–1985, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1986

Notes

[1] For an in-depth account of the Aboriginal people of the harbour see Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Historical Records, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 2010

[2] David Collins, The English Colony of New South Wales, vol 1, 1798, AH and AW Reed in conjunction with Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1975, pp 483–485

[3] IM Siminov quoted in Glynn Barrat, The Russians at Port Jackson 1814–1822, Aboriginal Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1981, p 34

[4] DH Lawrence, Kangaroo, 1923, reprinted by Heinemann, Melbourne, 1963, p 5

[5] See Joan Kerr and James Broadbent, Gothick Taste in the Colony of New South Wales, David Ell Press in conjunction with Elizabeth Bay House, Sydney, 1980

[6] See author, Ian Hoskins, Sydney Harbour: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 159–162

[7] Lachlan Macquarie quoted in Lionel Gilbert, The Royal Botanic Gardens: A History 1816–1985, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1986, p 20

[8] Kenneth Slessor, 'A Portrait of Sydney', in Gwen Morton Spencer and Sam Ure Smith (eds), Portrait of Sydney: A Photographic Impression, Sydney, 1950, p 11

[9] See author, Ian Hoskins, 'The Potency of History': The Site of the Museum of Contemporary Art', in Ewen McDonald (ed) Site, Museum of Contemporary Art, 2011, pp 113–132