The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Ultimo

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Ultimo

[media]Ultimo forms the southern half of the Pyrmont peninsula, bounded by Darling Harbour on the east, Blackwattle Bay on the west and Broadway on the south. Local understanding of the position of the northern boundary has varied over time, but is generally settled on Fig Street. Ultimo has always been part of the City of Sydney since its incorporation in 1842.

Country estate

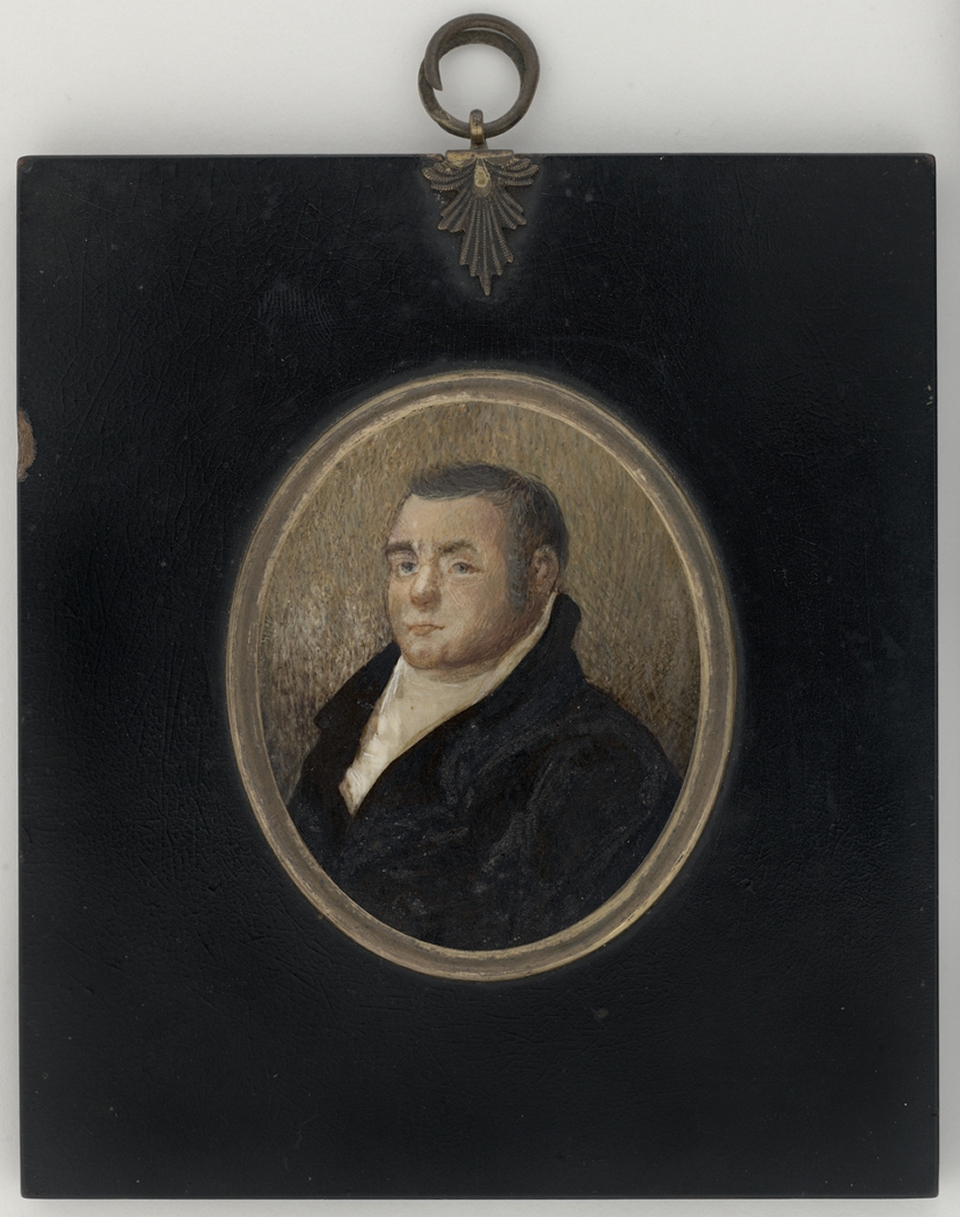

It [media]was part of the estate of the surgeon John Harris, who was granted 34 acres (14 hectares) 'between the church land' (The Glebe) and the ground used as a brickfield at the head of Cockle Bay, in 1803. Harris called his grant Ultimo Farm, in celebration of being acquitted in a court case on a technicality: namely, that the papers issued had used the Latin term 'ultimo', meaning 'last month', when they should have used the term 'instant', meaning 'this month'. Litigation seems to have been in the Harris family blood, as the rest of the Ultimo story will show.

Harris was granted further land on the peninsula, and by 1818, with additional purchases, he owned 233 acres (94 hectares) outright, covering Ultimo, much of adjoining Pyrmont and parts of the Haymarket.

The sandstone ridge that is the spine of the Pyrmont peninsula was covered at the Ultimo end by rich alluvial soil. This had attracted some early market gardens, but Harris's vision for his property was not development, but the creation of a country seat. In 1804, Ultimo House was built on the ridge to take advantage of the water views, and the surrounding land was manicured to resemble an English estate, complete with deer imported from India.

This idyll was not easy to maintain, as the property's poultry, sheep and especially deer were an irresistible temptation to convicts and soldiers billeted around the nearby brickworks. To make matters worse, by the 1820s, industries attracted to the watercourses in the area were established in Chippendale across Parramatta Street, (Broadway) with abattoirs making use of the hidden reaches of the Blackwattle Swamp beyond Harris's land. Harris moved out to greener pastures in 1821, and the house was rented out to other local luminaries.

Pubs and industry

By 1831, part of the estate facing Parramatta Street was sold off, and small commercial buildings soon appeared on this prime location, on the road into town. The Stonemasons' Arms, built in 1833, long since delicensed, still stands at 135 Broadway as a reminder of the nine public houses that lined the extremity of the Ultimo Estate by the early 1840s.

From 1840 neighbouring Pyrmont began to be subdivided, but it was mostly approached by water across Darling Harbour, and not via Ultimo. Until the 1870s the low-lying and swampy area behind Parramatta Street, from the head of Darling Harbour to the head of the Blackwattle Swamp, was the only part of Ultimo that was developed.

Here a jumble of workshops, slaughter yards, boiling-down works and other scrappy industries took advantage of the waters of Blackwattle Creek. Mixed in amongst all this were unsanitary little cottages, erected by landlords anxious to provide for the working poor, but not to provide much. Official reports, from the 1850s onwards, detailed cramped quarters, with people living cheek by jowl with domestic animals, with no water or sewerage, but any amount of flooding and sewage. Refuse and offal from the slaughter yards might be taken out on the tide, but often remained to rot on the mudflats. Floodgates, installed to hold back the waters and build up enough momentum to flush the area, were not always effective, as industrial users in adjoining Chippendale dammed the creek for their own use.

When government abattoirs were opened on Glebe Island in 1870, there were hopes that Ultimo's streets would no longer run with blood, but this also cut Ultimo out of the meat trade, and some illegal slaughtering continued.

The end of rural Ultimo

[media]The strip of Ultimo along Parramatta Street may have been the poorest area in all of late nineteenth century Sydney, and it was certainly one of the least pleasant. Behind it, Ultimo remained more or less rural. The initial grant to Harris had specified that a reserve be created for a road along the peninsula, and this evolved into Harris Street, but it carried little traffic. After Harris's death in 1838, legal complications frustrated subdivision of Ultimo until 1859 when the family squabbles were partially resolved and the land was finally distributed to a number of second- and third-generation family members. There were a few cottage-dwellers dotted around, using the land under grace and favour to run a few cattle or do a little local quarrying, while contemporary reports indicate that the area was so unsettled as to remain hospitable to Aboriginal people who still frequented the area.

Recent scholarly work suggests that the people living around Go-mo-ra (Darling Harbour) and the headwaters of the Blackwattle Creek may have formed a separate clan from the generally recognised Gadigal. Tentatively named the Gommerigal, this clan has yet to be officially recognised, but as late as 1830, Absalom West recorded the existence of a Darling Harbour 'tribe.' [1]

Railways and reclamation

The opening of the Pyrmont Bridge in 1859 made the peninsula more accessible, but this also had the effect of allowing traffic to bypass the Ultimo end of it. Local protest persuaded the bridge company to include a central swing span in the bridge, so that ships could still get to the upper reaches of Darling Harbour, and in 1853 the Sydney Railway Company acquired seven acres (three hectares) from the Harris estate, to build a rail terminus and goods yards. The line was opened in 1855, but as it did not extend to connect with the Pyrmont Bridge, the volume of goods passing through the yards was slight.

Visions of a railway terminus at the head of Darling Harbour were premature, and increased silting of the headwaters made this location progressively less attractive to shippers. The government was eventually forced to undertake reclamation and stabilisation of the 'slime' they had created, while the Harris family was successful in extracting both financial compensation and additional reclaimed land in recognition of the damage done to their estate.

Ultimo quarrying

While the building boom of the gold rush era largely passed Ultimo by, the rush to build fine public buildings in the centre of Sydney did have an indirect effect through the opening of several large quarries along the western flank of the Pyrmont peninsula. The stone had long been used on a small local scale, but by the 1850s its superior qualities as a building material was more widely recognised. The decision to use it in the construction of Sydney University at nearby Grose Farm provided enormous opportunities for quarrying, though most of the quarrymen lived in neighbouring Pyrmont. Needless to say, the university provided no direct benefit to the people of Ultimo, most of whom were too poor and too poorly educated to ever think of engaging with such an august institution.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, much of the western side of the peninsula was quarried and carted away to build Sydney's finest buildings. If there is one explanation of the tendency for Ultimo residents to feel that they came off second best in the rivalry that developed between the residents of Pyrmont and of Ultimo, it is probably that the name Pyrmont was applied not only to the whole peninsula, but also to the city's best stone, despite the fact that much of it was quarried in Ultimo.

The Harris family returns

When the land was finally available for subdivision, a third generation of Harrises moved back into Ultimo, both as landlords of extensive rows of terrace housing and pubs built from the 1860s onwards, and as residents. George Harris moved into Ultimo house, while his younger siblings built fine houses. John Harris built Bulwara in Jones Street, Matthew Harris built Warrane on Crown Road (later renamed Bulwara Road), while William Henry Harris's Livingstone and sister Margaret's Little Bridge were both on Harris Street. These families held extensive property in the area until at least the 1930s. The final resolution of the original carve-up of the land was only finalised in the late twentieth century, when an amount of money left originally to fund a dispensary was awarded to the Presbyterian Church, and used to establish the Harris Centre in the old manse of the Presbyterian church in Quarry Street. [2]

But, ultimately, Ultimo was not to be a place of fine houses, and none of these remain. Neither does the infamous early landmark Hancock's Tower, which was 40 feet (12.1 metres) high, complete with battlements and dummy guns. It stood behind George Street at what became Quay Street from 1840 until 1894. Robert Hancock, 'fence, womaniser and owner of notoriously bad hotels' evoked salacious gossip around town. Did Hancock have a lunatic wife locked up in his sinister-looking tower? Probably not, but there were plenty of children who declared that they had seen her white face peering from an upper window. [3]

Supporting a community

The residential history of Ultimo from the last decades of the nineteenth century and for the next century is a history of loss, as Ultimo was gradually turned into a prime industrial site. The draining of the Blackwattle Swamp to create Wentworth Park provided some recreational amenity, and the construction of churches and schools provided services to a population that was soon to be in decline.

In a precinct where work was irregular and wages were small, these churches, such as the Anglican St Barnabas's on George Street West (Broadway), were as much places of social service as of religion. Oral history from the early twentieth century, and right up into the 1950s, tells of survival in a tough neighbourhood. Grain taken from the back of a cart might feed the backyard hens. A kid could buy 'fags' for the wharfies in exchange for some desired product slipped from the wharf, or collect clippings of meat from the railway meat siding. The nearby markets were a source of damaged or 'surplus' fruit and vegetables, and if all else failed, the Benevolent Society was just down the road in Thomas Street. [4]

Slum clearance for industry

Houses were demolished to make way for large woolstores, from Richard Goldsbrough's, built in Pyrmont Street in 1883, until the last great store, Farmers & Graziers No 2 Store, replaced a swath of houses in 1936. When the City Council acquired the powers to resume land for slum clearances in 1905, the first place in its sights was the low-lying area adjoining Wentworth Park, along the line of the old Blackwattle Creek, by now an open drain. The Athlone Place resumption took out over 400 houses and displaced 1,779 people, according to the official count. [5] The town planning wisdom of the time dictated that houses be replaced with factories, and that people were better off living in the suburbs.

Many industries took advantage of the water and rail access, from large flour mills to small manufacturing, while the woolstores that came to line Wattle Street took advantage of the escarpment of the quarries that allowed them to use gravity in their operations. By World War II, over 1,000 men were employed in the 20 woolstores on the peninsula, most of them in Ultimo. These solid buildings covered more than 100 acres (41 hectares). [6] Their names are evocative of a time when wool was the nation's prime export; Pitt Son & Badgery, Elders, Winchcombe Carson and so on.

Many of these woolstores were constructed with timber beams, and soaked in wool grease with use they became highly flammable. Spectacular fires are part of the story of Ultimo, with the huge eight-storey Goldsbrough Mort & Co store burning down in 1935 and the AML&F fire lighting up the sky in 1992. Sometimes these fires would burn for days.

The Darling Harbour goods yards, with their related cold stores and bulk handling facilities, were ever-expanding. The head waters of Darling Harbour shrank accordingly, especially during the 1920s as rock tunnelled out for the city's new underground railway was dumped there – a rare example of sandstone coming to Ultimo, rather than being carted away. Freezing works and milk depots were located at the town end of Harris Street. One lighter side effect of this industry was the Glaciarium, a skating rink and meeting place on George Street West (later Broadway) run by the Sydney Cold Stores Ltd. The 'Glacie' was opened in 1907, and finally closed down in the 1950s.

Postwar Ultimo

By the 1950s, it seemed everything was closing down. Wentworth Park had been commandeered during World War II for use as an encampment for American soldiers stationed in Sydney on leave, with the result that some residents even had to carry passes to get to and from their own houses. After the war, temporary wool storage sheds remained in the park for years and further reduced public enjoyment of the park.

[media]The great Ultimo Powerhouse, commissioned in 1899 to power Sydney's electric trams and some of its trains, went out of service in 1963. The wool stores became empty shells when modern handling facilities were opened at Yennora in western Sydney. The city markets, which had occupied space at the head of Darling Harbour since the early years of the century, were closed and relocated to Flemington in 1968.

The clientele of the pubs where the workers had drunk disappeared. The state primary school in Wattle Street watched its numbers fall and the Catholic St Francis Xavier School in Bulwara Road closed its doors in the 1970s. St Alban's Anglican church in Ada Place, built in the 1880s, was sold to a private buyer in 1975, and the Presbyterian church in Quarry Street, built in 1883, was given over to the Dutch Presbyterians in 1960, as the local community no longer supplied a congregation.

Run-down houses became even more run down, and the streets became ever more clogged with traffic, as commuters struggled through Ultimo to get to the city. Plans for various freeways from the CBD and going in various directions promised to turn Ultimo into one giant traffic interchange, and many of the hundreds of properties that were 'DMR affected', where the Department of Main Roads had plans for freeways, became derelict.

From this low point, Ultimo has struggled back. Resident action groups, known as RAGs, fought the freeways, although by the time the Wran Labor government curtailed many of these plans in 1976, many houses had been demolished. About the only positive thing that could be said about Ultimo was that in terms of population and jobs, it did not collapse as heavily as next-door Pyrmont.

Education and cultural precinct

One thing that was never extinguished in Ultimo was its connection to technical education. Sydney Technical College, fronting Mary Ann Street, was built in 1892, while the Technological Museum nearby, fronting Harris Street, was opened the following year. As the new century approached, the 'Tech', in various incarnations, provided a new focus for industrial Ultimo, and opened up the possibility of further education through night classes in practical and applied sciences for many local lads and fewer local girls. It is fondly remembered in many reminiscences of life in Ultimo.

The college expanded into surrounding streets and newer buildings, eventually taking in the old Ultimo House, where the Sydney Technical High School held classes from 1911 until 1924. Sydney Boys' High was also housed in the precinct until 1928. Currently the Ultimo College of the Sydney Institute is the largest Technical and Further Education campus in Sydney. The Marcus Clark department store building on Broadway was purchased by the government in 1966 as part of the complex.

The NSW Institute of Technology also began as a unit of the Technical College. Its dominating tower block building was constructed in the 1970s on the site of the old Ultimo fire station building. This morphed into the University of Technology, Sydney, which was established in 1988. Since then it has spread out into many older buildings, including the old John Fairfax building in Jones Street where Sydney's most famous broadsheet, the Sydney Morning Herald, and other papers were published until 1995.

The old Technological Museum, renamed the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in 1945, was recreated as the Powerhouse Museum in the redundant cavernous spaces of the old power station in 1988, and is now the largest museum in Australia. A little further south along Harris Street is the headquarters of the Australian Broadcasting Commission, opened in 1991. Concerts at its Eugene Goossens Hall and Powerhouse museum exhibitions bring Sydneysiders to Ultimo, once a place almost unknown to outsiders.

The new Ultimo

Most dramatic of all, and most controversial, has been the creation of the Darling Harbour entertainment and convention precinct, on the site of the old railway goods yards. Turning this place of labour and industry into a place for spectacle and events, a place to stroll, play and eat, symbolises the enormous changes to Sydney's economy in a period of deindustrialisation.

There is now a new and wealthier population living in Ultimo than ever before in its history, living in new apartments or in converted woolstores. Old pubs have been turned into boutique establishments, and dining out is now a possibility where once it would have been unthinkable. Proximity to the city makes Ultimo an attractive location for city workers and for students, while employment in communications and computer industries offers a new kind of work. There is a sizable Chinese population in Ultimo, but whereas it was the work of the city markets that supported this population in earlier times, much of the investment now is from overseas Chinese, looking for a good investment or providing for student family members.

There also remains a core of long-time residents with older memories. Part of the fascination of Ultimo is its edgy mix of old industrial streetscapes and institutions with long attachments to the place, competing with the newest of urban developments.

References

S Fitzgerald and H Golder, Pyrmont and Ultimo: Under Siege, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1994

Michael Matthews, Pyrmont and Ultimo: A History, the author, Sydney, 1982

Notes

[1] Keith Vincent Smith, 'Eora Clans: A History of Indigenous social organisation in coastal Sydney, 1770–1890', MA thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, 2004, pp 70–72

[2] John Harris, 'Ultimo and the Harris Family', in Michael Matthews, Pyrmont and Ultimo, A History, the author, Sydney, 1982

[3] Geoffrey Scott, Sydney's Highways of History, Georgian House, Melbourne, 1958, pp 56–59

[4] S Fitzgerald and H Golder, Pyrmont and Ultimo: Under Siege, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1994, pp 102–4

[5] Proceedings of Sydney City Council, 1905, Town Clerk's Report, p 85, and Proceedings of Sydney City Council, 1912, p 256

[6] Michael Matthews, Pyrmont and Ultimo: A History, the author, Sydney, 1982, pp 69–77

.