The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Damming the Cooks River

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Fresh water for a growing town

Choosing a site

[media]The Cooks River dam was located in the position of the present bridge on the Princes Highway at Tempe, New South Wales. Construction began in 1839 and was completed in 1842. It was demolished between 1896–99. [1]

'The greatest boon ever conferred upon the town'

The Cooks River dam was built because a new water supply source was urgently needed for Sydney. Water from the old Tank Stream had been abandoned in 1826, and the carting of water from the Lachlan Swamps (now Centennial Park) through Busby's Bore until the 1830s showed a need for a better and more cost-effective fresh water source. The Cooks River was considered the most convenient. [2]

[media]By the end of 1838, water was on the minds of all Sydneysiders as New South Wales dealt with a severe drought. Local magnate Alexander Brodie Spark, resident of the farm Tempe [3] on the south bank of the Cooks River, recorded in his diary two early conversations about the Cooks River dam: [4]

Had a conversation with the Governor on the subject of damming up Cooks River for the purpose of obtaining a constant supply of fresh water for Sydney.

Governor Sir George Gipps was clearly interested in the idea and [media]sent for Colonial Engineer Major George Barney to survey the river near Tempe, and Spark gave his approval four days later for the dam's location across his private property:

Major Barney called on me afterwards in town and said that if I did not object to it the dam might be run across below the Bathing house, and the only apprehension was that my garden might be flooded. To be surrounded with the fresh water instead of salt would be highly desirable and I did not object to his proposal if he could previously ascertain that no bad consequences would follow.

Governor Gipps believed the dam would 'preserve an inexhaustible supply of fresh water through a course of nearly twenty miles' (32.1 kilometres) and claimed it to be 'the first operation of the sort upon a large scale' constructed in the colony. [5] The Sydney Gazette of February 1839 described the substantial dam's erection:

...in order to prevent the ingress of salt water. A canal is then to be cut through the country from the spot to within about a mile of Sydney whence the water will be conducted into the town in pipes...this measure, when completed, will prove the greatest boon ever conferred upon the town. [6]

Constructing the dam

[media]The Cooks River dam, with sluice gates at its northern end, cost £4,078 and was paid for by the colonial treasury. This amount covered all costs except feeding and housing the convicts who were used for labour. [7]

Convicts from the next two Sydney bound prison ships formed an eventual gang of 500 who constructed the dam. [8] It was initially completed by 200 men, with a further 170 men in 1839. They lived on the north side of the river in a temporary stockade. [9]

The unemployed also formed part of this working group. Rations were provided, with families receiving 26 pounds (11.8 kilograms) of meat and a slender ration of sugar and tea per week. They walked five miles (eight kilometres) to and from the dam and in 1844 it was suggested that tents be provided nearby, to make their journey to the dam less arduous. [10]

The gang constructed the dam with sandstone quarried from the nearby cliffs along both sides of the Cooks River, and its construction allowed Spark a pleasing access road from his Tempe estate into Sydney. [11] A tollgate was erected, showing the entrance to Sydney Town.

[media]Many of the large number of workmen who were brought to the village of Tempe to build the dam chose to settle in the district. By 1850 the social mix of the area was said to have altered because of the influx of fishermen, charcoal burners, woodcarters, and limekiln shell-gatherers. Sporting Magazine of 1850 claimed: '...the echoes of Tempe are degraded by the woodman's slang or the limeburner's orgies.' [12]

A meeting place for sport

The Cooks River dam served as a meeting place for all kinds of local sport and was a well-known landmark in the Cooks River valley. Men met at the dam for hunting appointments of several day's duration, kangaroo and deer being prolific in the district. Alexander Brodie Spark recalled in his diary in 1838 that deer sometimes became entangled in the river mud near his Tempe estate. [13] By the 1850s men were also hunting dingo in the area of the dam, and Governor Sir Charles FitzRoy conducted meetings at Cooks River dam in the early mornings. [14]

Racing was also popular at the dam and newspapers of the 1850s record regular sailing matches, boat races and horse races. [15] By the 1870s people also enjoyed pigeon shooting. [16]

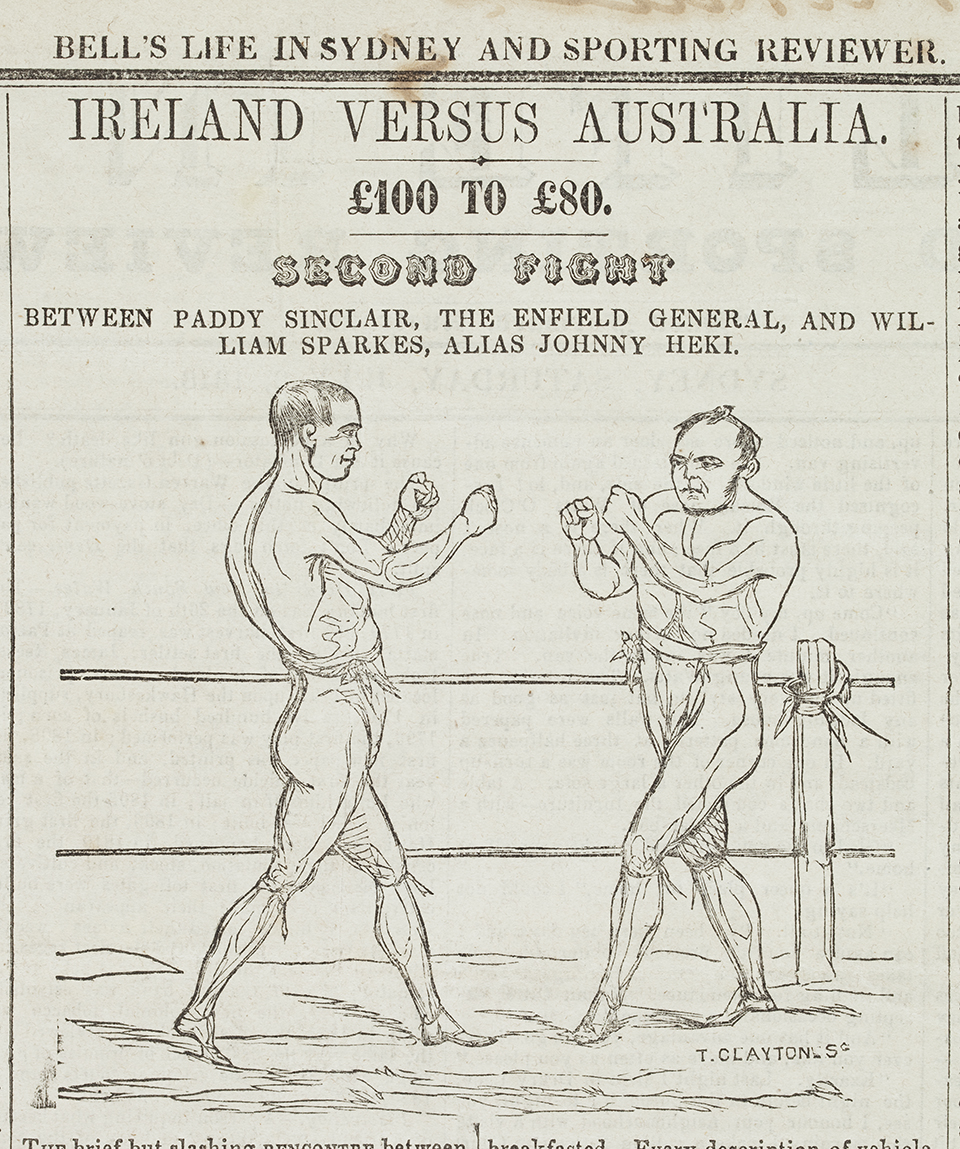

[media]During the late 1840s and 1850s, illegal boxing contests were secretly held at the 'thickly wooded copse' opposite the Cooks River dam and in its district. Contests were for bareknuckled fighting, with prize fighting winnings often up to £50 a side. Constables or 'peelers' kept a lookout for these fighters, who used witty aliases and whose eager spectators remained anonymous. A ring would be established in a secret clearing in the bush and local publicans had much to gain from these pugilists as word of their challenges would be issued around local pubs. [17] Close drinking holes to the Cooks River dam were The Real Ould Sportsman's Union Hotel run by Irishman Michael Gannon and the Pulteney Hotel run by Joseph Cook, with both establishments known to support the sporting life. [18]

[media]Two Cooks River pugilists of note were Joe the Basket Maker and his wife Elizabeth Hilton, better known as 'The fighting hen of Cooks River'. Both were well-known for their love of a bareknuckled fight, and Joe advertised that The Fighting Hen was willing to take on any person, man or woman. [19] When the couple wasn't employing fisticuffs, they moonlighted as boat hirers at the Cooks River dam. [20]

A sombre meeting place

In the 1860s the Cooks River dam was the regular meeting place for more serious gatherings such as funerals, and crowds would proceed from there in a slow procession to the cemeteries at St Peters or Petersham. By the 1880s it was the site of some infanticides, as the Singleton Argus of 23 June 1887 lamented:

Another dead body of a newly born infant was found on the banks of the Cooks River dam, Cooks River today. It had evidently been strangled by means of a pocket handkerchief, which was firmly tied around the child's neck. The doctor expresses the opinion that the child was born alive. [21]

Flooding and pollution

Although the dam's completion in 1842 gave a new solid transport link to the city, allowing a road to Illawarra through the forest (Forest Road), [22] it quickly caused problems of pollution and flooding. The river was said to flood every time there was a heavy downpour. After a rainy, windy night in April 1841, Spark wrote: 'the river has overflown the dam, and the whole of the lower ground is underwater.' [23] It was to flood many times over the next decades, causing destruction to property, poisoning of the river's rich marine life and creating menacing health hazards from the deposition of sewerage from cesspits.

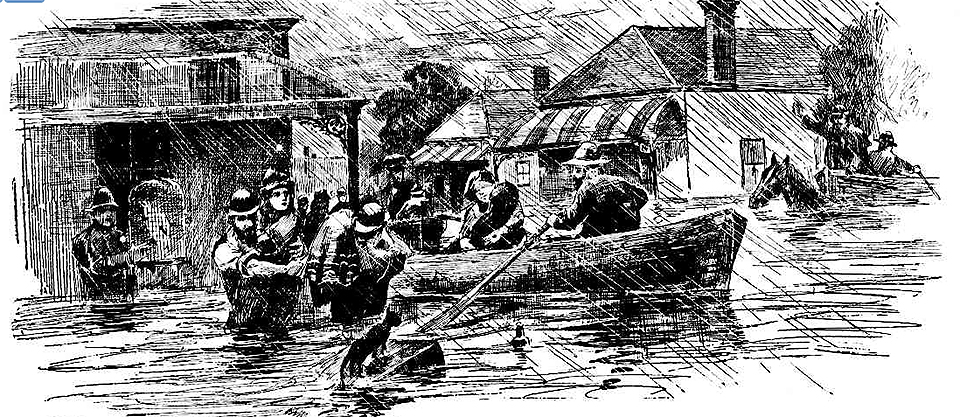

[media]The flood on Queen Victoria's 70th birthday on 24 May 1889 was memorable for the 17 inches (43.1 centimetres) of rain over one weekend, which caused the workmen and artisans of Tramvale estate to be rescued in rowing boats. Chinese market gardeners working terraces along the riverbanks became homeless after their houses were destroyed. [24]

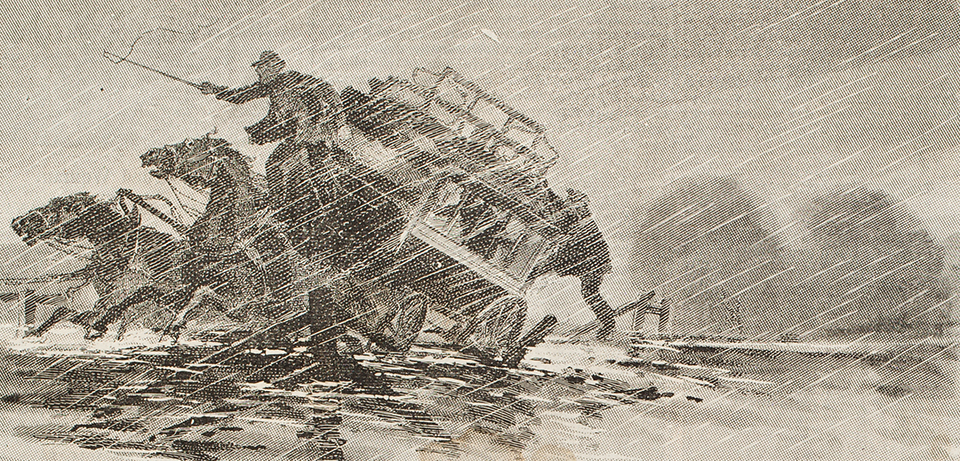

The Sydney Morning Herald reported [media]the deaths of a fare boy and four horses after George Coleman's omnibus containing passengers was dragged into the flooded river at Prout's bridge. The body of the fare boy was discovered the next day, 200 yards (182.8 metres) from the bridge, with his fare bag still attached to his body. [25] This flood was significant as it caused the river to rise as high as ten feet (three metres) above the Cooks River dam. [26]

Complaints and complainants

It seems the Cooks River dam was a never ending source of environmental blight and misery to Sydneysiders throughout its 60 year life. Sydney newspaper articles abound with tales of its repairs and ongoing alterations. In July 1857, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that repairs were necessary because the dam '...at present is in a most dangerous and almost impassable state.'

The government granted only £300 and the local inhabitants of Tempe, Kingsgrove, Gannon's Forest and Georges River were expected to assist with 1–3 days labour or money, as the government sum was not adequate to meet the cost of repairs. [27]

By November 1862 a new wastewater channel with timber gates and a bridge was added to the dam [28] and by 1875, as the government Gazette recorded, a tender was accepted from 'Messrs Moir and Jennings' for the erection of extra floodgates. [29]

[media]At the end of 1877 the Cooks River dam tollbar ceased to exist. [30] Three months later, a deputation of local mayors and members of parliament visited the minister for works, urging for a fence to be constructed, as the crossing place at the dam was in a dangerous condition. The planking over the floodgates was very loose and needed repair and lives had been lost, horses drowned and the crossing remained a great risk to women and children. [31]

Reclaiming the mangrove swamps

[media]During the 1880s the Cooks River was a regular swimming, boating, fishing, picnicking and strolling destination for locals and weekend pleasure seekers in search of refuge from Sydney, yet its poor condition was still an ongoing concern. The Sydney Morning Herald of 21 October 1886 paid this issue some attention:

...this has been especially the case in the summer months, when the hot rays of the sun caused the mud flats and mangrove swamps which line both sides of the channel below the Cooks River Dam, to emit sickening stenches. [32]

Three months later The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser gave extensive copy to the issue, outlining in detail the reclamation plan for the 800 acres (3.2 kilometres sq) of mangrove swamps at the Cooks River dam. This plan had a threefold aim: to fix river sanitation, to create a navigable channel with deep water to enable vessels to reach the dam's government wharf and to create local work for the unemployed.

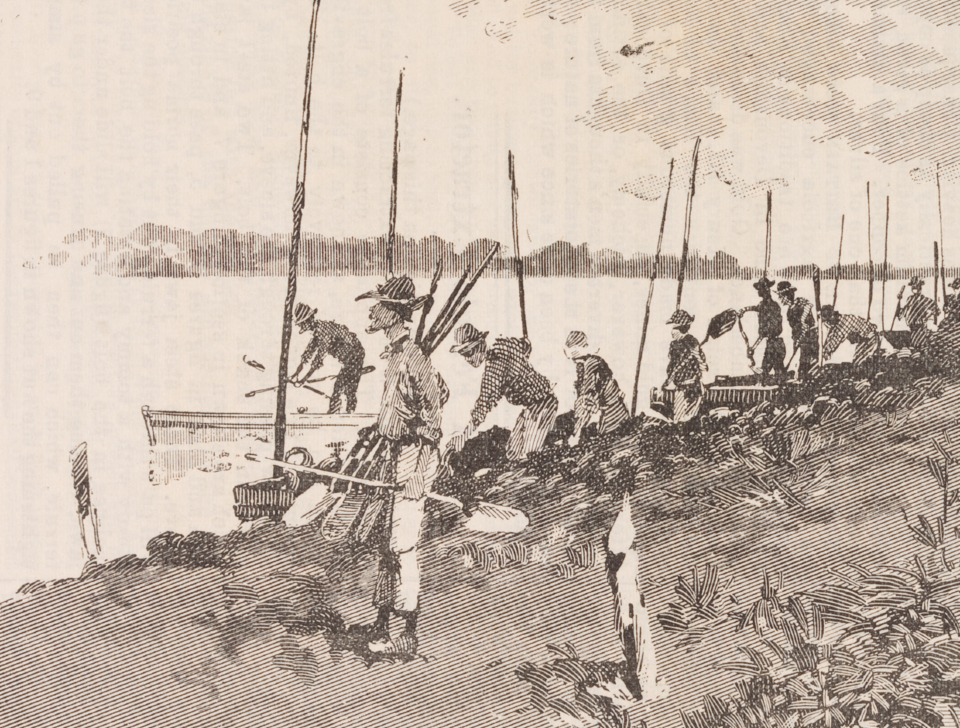

[media]Reclamation work began on the marshy land in December 1886 and soon 50–60 acres (20–24 hectares) had been cleared under the supervision of Alfred Williams, the Assistant Engineer for Harbours and Rivers. It was believed that this work would transform the Cooks River flats into valuable areas. 120 men worked at the dam, with 35 others engaged cutting ti-tree for the embankments at Georges River. [33]

The silting up of the channel meant that only the very lightest draught of vessel was able to reach the government wharf that had been constructed several years earlier. For most vessels, the wharf remained useless because only small boats were able to use the waterways to access roads. These carried Sydney cockle and Sydney rock oyster shells (probably from early Aboriginal middens), as well as ironbark and turpentine timber from the ridges and casuarinas from the riverbanks. The timber and seashells were the raw materials for the building industry; lime was in high demand because Sydney had no natural limestone for building. [34] The waterways however also needed to accommodate larger boats and so the river began to be made deeper and wider.

Work began to create a depth of water nine feet (2.7 metres) for the whole channel from Botany to this wharf, with a width of 400–500 feet (122–152.4 metres). This allowed larger vessels to reach the wharf and enabled the river to be effectively used for manufacturing purposes.

The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser described in great detail aspects of the reclamation project on 4 August 1887:

The reclamation works commence at the limekilns, immediately below the Cooks River dam, their main features being the construction of substantial embankments on either side of the river, and the dredging out of the channel between to the required depth. The embankments are being constructed on an ingenious but simple principle, by means of faggots of brushwood from the ti-tree...over 800 of these faggots are used for each 100 feet (30.5 metres) of the embankment. [35]

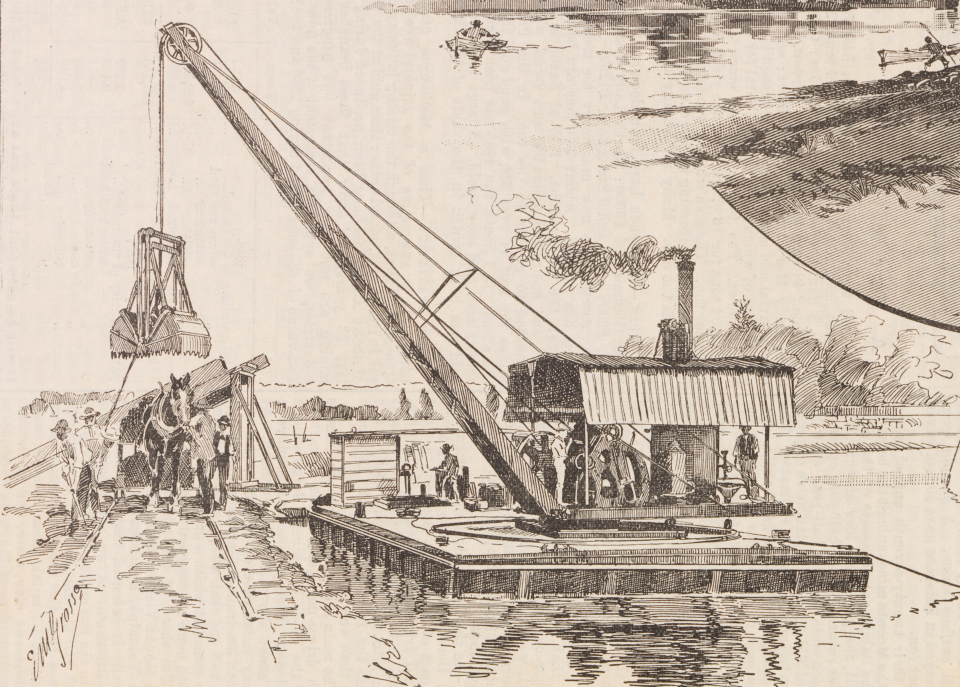

[media]The dredges were described:

...two steam grab dredges, the Epsilon and Kappa, are at work clearing out the channel, the silt thus obtained being utilised to fill up the reclaimed ground on either side of the river...the ground made in this way becomes in a short time so solid and compact that drays can be hauled over it, and as the soil, which contains a large percentage of lime, soon sweetens, vegetation is even now beginning to spring up in several places.

An astonishing 300 tonnes (304,814 kilograms) of silt was removed by the dredges each day from the bed of the Cooks River and deposited within the embankments. A temporary tramway was built along the top of the embankment on the northern side of the river to move the silt.

The total cost of the reclamation at this stage was £7,362, with at least 80 workers belonging to the unemployed class and the majority paid five shillings per day. They were mainly local men who had previously worked at the St Peters brickyards and other nearby works.

A conference of councils

Despite the extensive reclamation project, four years later The Sydney Morning Herald was still reporting problems at the Cooks River dam. In July 1891, the works department feared that the dam would give way due to its appalling condition. Marrickville, St Peters, Rockdale and Canterbury councils were invited to a conference to discuss its future. [36]

Following this conference, a further dam conference was called at Marrickville town hall on 24 April 1895. Alderman Benson from Marrickville moved that aldermen from these councils create a committee to urge the government to dredge Cooks River all the way from Cooks River dam to the Sugarworks dam in Canterbury 'which under present conditions, is a menace to the health of the residents of the said municipalities.' This motion was carried unanimously. [37]

'A terrible stink'

Although the Cooks River had been dammed to supply fresh drinking water for Sydney, the solid dam wall was made of porous sandstone and so the water remained brackish and unable to be drunk. Pollution only increased as the population along the river expanded, with household slops, rubbish and sewerage from cesspits continuing to be dumped in the river.

By the time of the 1896 examination of the improvement of the Cooks River, Canterbury Mayor Sydney Lorking told the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works that the Cooks River dam was the chief cause of the pollution. It caused most of the silting and encouraged weeds, with floating timber debris causing 'a terrible stink.' It remained a public health issue with children contracting typhoid and other illnesses from swimming in the river.

The general sentiment of local people at the time shared Lorking's view that the dam was the main culprit. They believed it encouraged salt into the water, slime mud on the river bottom instead of sand and gave rise to long reeds. Witnesses noted that the dams stopped the tides from cleaning the river. By the 1890s:

...the odours arising from Cooks River had achieved a worldwide reputation. A health inspector discovered cows with typhoid drinking the river water and people were warned against bathing. The settlers who had used the river as a drain and a waste depository were now suffering for their folly. [38]

In 1896, Mr HB Henson presented a paper to the Engineering Association of NSW and put forward several long-term recommendations to fix up the Cooks River. He too believed the dam encouraged silt, prevented tidal flushing and during heavy rain made flooding worse. Henson advised complete removal of the dam and suggested building a tunnel and canal from the Parramatta River through Dulwich Hill and into Cooks River. He also believed that water from Sydney Harbour could sweep away the silt and he advised joining the Parramatta and Cooks River by a second canal. Henson's novel plan was not taken up and instead more dredging of the Cooks River was proposed. [39]

In May 1896 the Minister for Public Works, James Young, put the Cooks River Improvement Bill forward. An estimated £56,000 was provided for works near Tempe to discharge floodwaters and improve sanitation. [40] There was support and some opposition to this bill and once it was referred to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Public Works, it was approved but with a cut of £41,000. The balance of £15,000 was spent extending and widening the sluice gates, lowering the sills at the southern end of the dam, dredging and building an embankment with escapes for floodwaters across Marrickville Creek. [41]

The Cooks River Improvement Act of 1897 targeted the Cooks River dam but pollution and flooding continued unabated. [42] Finally a bridge with tide gates was constructed [43] and the Cooks River dam drew its last fetid breath when it was demolished between 1896 and 1899. [44]

The Sugarworks dam at Canterbury

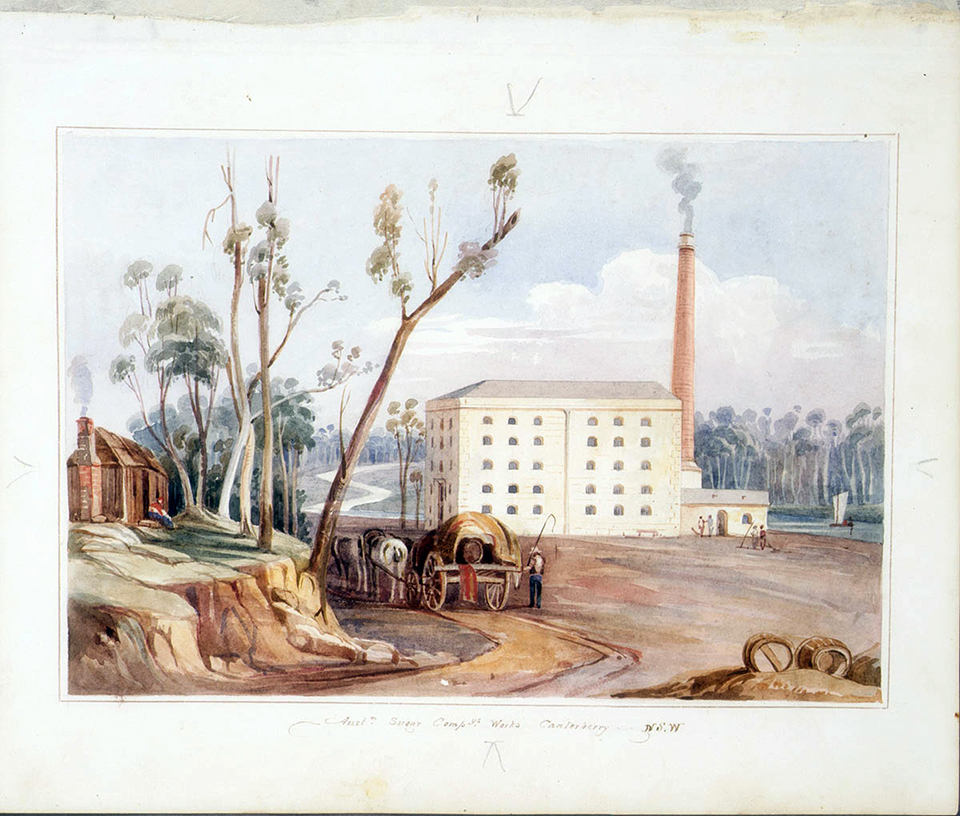

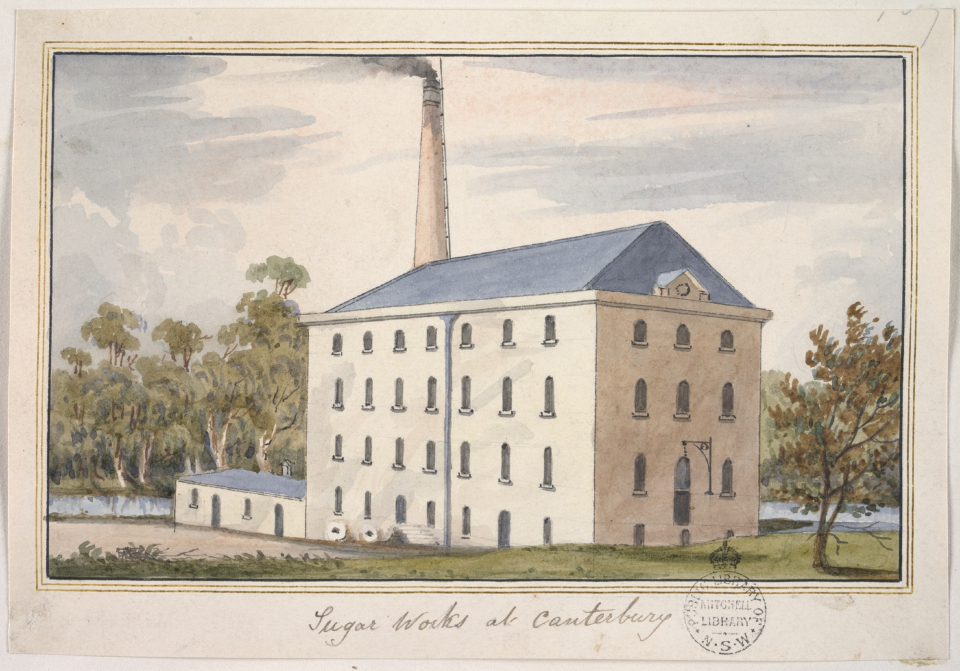

[media]The Sugarworks dam and footbridge were located near the present footbridge beside the two surviving heritage listed sandstone Sugar mill buildings (now Sugarmill Apartments) at 2–4 Sugar House Road, Canterbury, New South Wales. The dam was constructed in 1841 [45] and was still standing in 1913. [46] The dam and sugar house were the reason for the establishment of Canterbury village.

The dam was built to provide a plentiful supply of fresh water to the boilers of the Australian Sugar Company refinery at Canterbury; the refinery was the Cooks River's first manufacturing industry. The dam's fresh water also served the pioneering efforts of the New South Wales woolwashing industries.

The dam was 'built of beautiful white sandstone' [47] quarried in what is today Hurlstone Park and had stepping stones along the top. [48] Its contractors were William Lucas and his politician brother, John Lucas, who represented the electorate of Canterbury from 1860 to 1880. [49]

John Lucas was greatly interested in Sydney's water supply. [50] In a letter to the editor of The Sydney Morning Herald on 2 February 1883, John Lucas wrote of the dam's ability to bring fresh water:

During the year 1841 I constructed a dam across Cooks River for the Australian Sugar Company, and in a fortnight the inhabitants of the village of Canterbury were using the water for all domestic uses. [51]

Building the Sugarworks dam

The Sugarworks [media]began to be constructed in late 1840 and was built by Scottish stonemasons supervised by David MacBeth. Sandstone was quarried by the Cooks River, and ironbark from the bush on the opposite side of the river was used on the inside of the building. Its walls were made of sandstone one metre thick. [52]

The building was erected within 100 feet (30.5 metres) of the river. It was six stories high, with six spacious floors including a mill, storerooms, a boiler and engine houses. These were worked and heated by a powerful steam engine that drove a mill which grinded animal charcoal. The manager William Knox Child brought the machinery to Canterbury from England.

Child brought 'forty engineers and superior workmen conversant with sugar refining' as well. More than 100 workers built the Sugarworks and lived in slab huts in the vicinity. Forty children attended the nearby school, which on Sundays was used as a church. [53] It was described as having 'promoted great harmony and excellent demeanour throughout the township.' [54]

The construction of the Sugarworks led to a small population of around 300 people, concentrated in the village of Canterbury. [55] Butchers Thomas Austin Davis and John Quigg established the first stores, and early shopkeepers were James Slocombe and Barnabas Hartshorne. The Canterbury Arms public house was licensed in 1843. [56] At the height of production, there were two churches, a school, and three public houses. [57] By 1879 there were many more merchants including a bootmaker, butcher, tailor, saddler, blacksmith, nurserymen and general and produce storekeepers. [58]

[media]In 1843 the Australian Sugar Company refinery became the Australasian Sugar Company, managed by Edward Knox. The Sugarworks by this time produced crushed sugar, loaf, molasses and vinegar from raw sugar imported from the Philippines. In 1849–50 a new road was built between Sydney and Canterbury (New Canterbury Road), which allowed workers to bring raw sugar more easily from Sydney by cart to the Sugarworks. [59]

Newspaper advertisements for land surrounding the Sugarworks and dam in the 1840s and 1850s describe 'the constant employment and happy condition of everyone about the sugar works.' Advertisements mention supplies of building bricks procurable from a nearby kiln and deep water of the 'purest description' due to the dam's construction. Stone and firewood are described as being in abundance.

By 1856 the area around the Sugarworks and dam had been subdivided into farms. Labouring classes were employed gathering charcoal, sawn timber and firewood, growing vegetables, raising poultry and collecting eggs and dairy produce. [60] Photographs of the time depict tranquil pastoral scenes of people crossing the wooden footbridge over the dam and horses and cows grazing on the south bank of the Cooks River.

The Sugarworks closes its doors

Due to shareholder dissent and a labour shortage caused by the gold rushes, [61] the Sugarworks ceased operation in August 1854. The closure greatly disadvantaged the village of Canterbury and its population fell from 473 in 1851 to 319 in 1861. Schools, churches, stores and inns were forced to close and the village took some time to get back on its feet. [62] It regained life in the 1890s when a railway and permanent industry came to Canterbury. [63] The Sugarworks, now considered the earliest landmark dedicated to the Australian sugar industry and the oldest building in the municipality, remained deserted and in disrepair for the next 30 years. Its purpose built dam remained.

Noxious industry and pollution

The village of Canterbury continued on, as the construction of the Sugarworks dam had encouraged other industry to the area and served it ably, leading to deterioration in the condition of the Cooks River.

Woolwashing

In the 1860s, wool prices were very high and by 1863 Samuel Lucas had established a primitive woolwash on the western riverbank. Like the Sugarworks, the woolwashes around the dam offered employment for a lot of people, as did the timber industry:

Timber-getting was also followed in the thickly wooded Canterbury district, and the sight of bullock teams drawing the squared timber into Sydney along Old Canterbury Road and returning laden with sugarcane and wool was of daily occurrence. [64]

In 1868, businessmen Frederick Clissold and George Hill set up a more elaborate woolwashing industry on the river on the eastern bank opposite the desolate sugarworks. By July 1868, greasy, fetid scum from these woolwashes started to build up near the stonework of the Cooks River dam at Tempe. The refuse water was so polluted that the prawns and fish, which had previously been abundant in the Cooks River, disappeared. [65]

Serious complaints about the Clissold and Hill woolwash abounded in The Sydney Morning Herald during 1868. The water used for wool scouring led to impurities being washed into the river, with numerous letters received by Marrickville council complaining of its poor health. Complainants noted that the river was not fit to swim in, and that its fish had been poisoned. In a letter to the editor of 20 June 1868, 'An Inhabitant' described the changes to the river:

...the river, instead of being limpid, as formerly, is full of impurities caused by wool washing. Indeed, it could hardly be otherwise, for there is a dam above and a dam below the place where the foul mixture is discharged into the river. [66]

Two weeks later the Mayor of Marrickville, Charles St Julian, visited the river by boat with two council aldermen and made a report on the woolwashing establishment at Canterbury, showing that residents' complaints were well founded:

A greasy scum was gathered about the floodgates and the stonework, in their vicinity. Smaller accumulations of a similar scum were observed at various points along the banks of the river, and minute particles, of a woolly character, were floating in the water throughout the whole of the distance. Occasionally there was a very perceptible odour of the kind usually met with in the vicinity of wool washing establishments. This appeared to be caused by the accumulation of refuse matter among the herbage on the banks of the river...these evidences of pollution were as strong, at intervals, in the lower portion of the river as near to the establishment in question. [67]

They noted the alarming alteration of the river's marine life:

That as one result of this pollution the river no longer, as heretofore, abounds with fish, and that, in particular, the prawns for which it was once celebrated are not now to be found in it. That at times, especially during hot weather, the river at many points emits – from the causes already mentioned – an absolute stench.

And described the river's risk to public health and private property:

Already much injury has been done...by the pollution of the river to such an extent as to render it unfit for bathing purposes. Already are those who reside in its vicinity annoyed, and the value of their properties diminished. These injuries and annoyances must increase, the public health must be endangered, and the value of property near the river must be still more seriously diminished, unless the nuisance complained of be effectively and permanently abated.

By August 1868, Clissold and Hill remedied their polluting woolwash by carefully straining and filtering the enormous quantities of water used. They raised fresh water from one side of the dam with a noisy, powerful steam pump, then cleansed the wool and released the water on to the other side of the dam. When working continuously, the pump at full power was able to raise more than four and a half million gallons (20, 457 million litres) in over 24 hours. [68]

In spite of this, a boating visitor to the Canterbury area described the river's murky condition in August 1868:

Our boat had to be lifted or 'ported' over the dam at Canterbury, but this was accomplished without much difficulty. Near the wool-washing establishment the water has a rather muddy look...the water below the Canterbury dam is generally brackish, as the salt water passes freely through the dam at Tempe. It has been said that even above the Canterbury dam it is a little brackish. [69]

Interestingly, the problem of pollution was overlooked by prominent local wool merchant and politician Thomas Holt of The Warren. He was still able to proclaim in a letter to the editor of The Sydney Morning Herald on the first day of 1872 that the dam at Canterbury was 'now the life and soul of that township.' [70]

Other noxious industries

The Sugarworks dam also served other noxious industries. During the 1870s the price of wool began to fall, and by 1875 Clissold and Hill's woolwashing premises were taken over by a gold stamping works. A gold extracting machine patented by Messrs Lawson, Jaffray and Company was erected for the extraction of gold and silver from mineral and quartz substances. Tailings from the Tambaroora gold field were brought to Canterbury to be crushed in this machine. [71] The gold stamping works failed within a year, possibly because the site was not close enough to rail. [72]

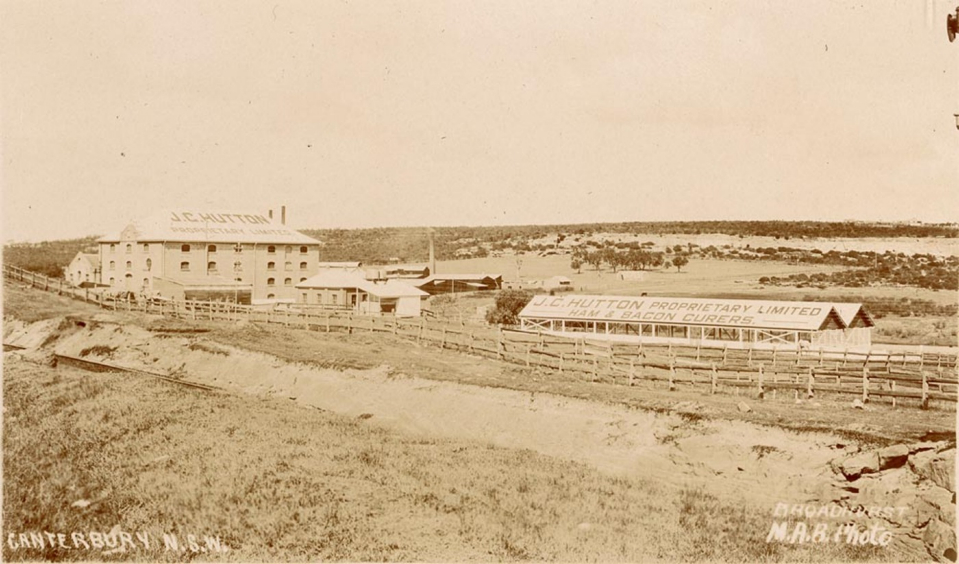

Denniss's Tannery operated opposite the Sugarworks and was run by Jeffrey Denniss, an alderman of Canterbury City council from 1895 to 1908 and mayor from 1900 to 1903. A successful tannery was also established by Mr EJ Tebbutt on Clissold's land, boasting 26 tanpits with six lime pits and surface drainage. William Mayne utilised the old woolwash buildings of Samuel Lucas to boil down cattle and horses which had died of old age or disease. A bacon curing factory and slaughterhouse also began operating along the riverbanks. The industrial waste from these establishments continued to slowly pollute the Cooks River, making the dam's water unsuitable for drinking and increasing the risks to public health. [73]

By 1882, the Royal Commission on Noxious and Offensive Trades [74] listed Mayne's boiling-down establishment and Tebbutt's tannery as the main culprits due to unfiltered drainage washing straight into the Cooks River. [75] Other wastes dumped in the Cooks River included sewerage farms, effluent from soap factories and septic tanks. [76] By 1896 the pollution was so serious that some people who had swum in the Cooks River died from an outbreak of typhoid fever.

Heavy industry

[media]In 1880 Frederick Clissold purchased the abandoned Sugarworks building for the purposes of investment. Clissold sold it four years later to Owen Blacket, son of Edmund Blacket, who refurbished and used the site from 1882 to 1885 as an iron foundry and heavy engineering plant. Local people had been pressing the government for a railway line to be built from St Peters to Liverpool, which they hoped would run past the Sugarworks dam area. Blacket believed the Sugarworks at the dam would be a prime site for the location of railway engineering. The government delayed this decision and their tardiness led to Blacket and Company filing for bankruptcy. The sugarworks was then abandoned again.

In 1890 the Sugarworks building housed Foley Brothers' butter factory. From 1899 to 1908 it was purchased by Denham Brothers and operated as the Canterbury Bacon Factory.

Sylvan memories of the Sugarworks dam

[media]In the early years of the twentieth century, writers started to reminisce about the 'good old days' of the Sugarworks on the Cooks River. RB Parry wrote of his nineteenth century memories in The Evening News of 14 November 1908:

In the vicinity of the old sugar works, and looking down the river towards Undercliffe, the visitant of today would scarcely believe that here only a few years ago there flourished ferns in great variety, waterlilies, the gay epacris, grandifloras, waratahs, native roses, and last, but not least, the golden blossomed wattles, rendering the air redolent with their powerful perfume. Alas, tempora mutantur! With the advent of the iron horse the romantic has vanished before the utilitarian. One may look in vain for the pleasant boating parties that oft frequented this locality, and lifting their rowing boats over the dam, where the tannery now stands, passed up between the gardens in the direction of picturesque Croydon Park, to cast in their rods for mullet, or to gather the much coveted ferns, or to picnic to their heart's content amid surrounding ferns and foliage. [77]

In 1911, a Canterbury municipality deputation asked the minister for works for the dam across Cooks River to be removed, with a sewerage scheme initiated for Canterbury, Campsie, Belmore and Enfield. As The Sydney Morning Herald reported:

...the river had become 'little less than a sewer' and that above the dam, when the water was low, an intolerable nuisance existed. Unless something was done promptly, a crisis in the matter of the health of the suburbs concerned would be brought about. The Minister, in reply, said he regarded sewerage as a necessity of civilisation, and he intended to give every municipality that could pay for it a proper system...a scheme for Campsie alone would cost £100,000 and one for the whole area would run into something like a million sterling. He fully realised the importance of the matter. For the death of every child from typhoid, because of the want of a proper sewerage system, the government of the day should be held responsible. He promised to submit the matter to the Public Works Committee as soon as Parliament met. As to the removal of the dam, he would personally visit the locality on Wednesday. From the case made out by the deputation it seemed probable that he would order the removal of the dam at once. [78]

In 1913, the Sugarworks dam was reported to be firmly standing. Canterbury council made attempts to get the dam removed to make the Cooks River a tidal system to Liverpool. The government on many occasions refused to indemnify the council. Owners of small industries along the riverbanks above the dam, as well as market gardeners, threatened the council. They warned that if their industries were damaged because of salt water mingling with fresh due to the dam's removal, they would make trouble. The council understood that the only way to remove the dam would be by an Act of Parliament. [79]

References

Bell's Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 1845–1860, George Ferrers Pickering and Charles Hamilton Nicholas, Sydney, NSW

New South Wales Royal Commission Appointed on the 8th January, 1880, to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Fisheries of this Colony, Report of the Royal Commission appointed on the 8th January, 1880, to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Actual State and Prospect of the Fisheries of this Colony: Together with the Minutes of Evidence and Appendices, New South Wales Parliament, Sydney, 1880

Archives of the Australian and Australasian Sugar Companies, 1840–56, Noel Butlin Archives, Canberra

Alexander Brodie Spark diaries, 1 January 1836–22 September 1856, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, A4869

'The Cooks River Portal', CookNet, City of Canterbury website, http://www.canterbury.nsw.gov.au/www/html/170-cooknet---the-cooks-river-portal.asp

Notes

[1] 'Cooks River dam', Dictionary of Sydney website, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/structure/cooks_river_dam?zoom_highlight=cooks+river+dam, viewed 9 December, 2013

[2] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 58

[3] Tempe, now known as Tempe House, was a home built on the banks of the Cooks River by Alexander Brodie Spark that became a social mecca for Sydney's merchants and bankers. It is a rare remaining example of Neo-Classical Georgian architecture in Sydney; 'Tempe House', The Dictionary of Sydney website, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/building/tempe_house?zoom_highlight=tempe+house, viewed 19 May, 2013

[4] AB Spark, 5 and 9 November 1838, in Alexander Brodie Spark diaries, 1 January 1836–22 September 1856, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, A4869

[5] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 58

[6] The Sydney Gazette, 5 February 1839

[7] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 58

[8] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 58

[9] Letters to the governor from the colonial engineer, 1831–1846, Colonial Secretary's Correspondence: Special Bundles, 1846–56, NSW Civil Establishment, Returns of the Governor, State Records Authority of New South Wales, 4/7344

[10] Morning Chronicle, 13 November 1844, p 2

[11] Letters to the governor from the colonial engineer, 1831–1846, Colonial Secretary's Correspondence: Special Bundles, 1846–56, NSW Civil Establishment, Returns of the Governor, State Records Authority of New South Wales, 4/7344

[12] Reprinted in The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 July 1935

[13] AB Spark, 27 June 1838, in Alexander Brodie Spark diaries, 1 January 1836–22 September 1856, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, A4869

[14] The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 July 1850

[15] 'Cooks River Nineteenth Century Sporting Life', St Peters Cooks River History Group website, http://stpeterscooksriverhistory.wordpress.com/2011/10/11/cooks-river-nineteenth-century-sporting-life-2/, viewed 29 November 2012

[16] Australian Town and Country Journal, 22 October 1870

[17] 'Pugilism', St Peters Cooks River History Group website, http://stpeterscooksriverhistory.wordpress.com/2011/10/11/cooks-river-nineteenth-century-sporting-life-2/, viewed 29 November 2012

[18] 'Cooks River Nineteenth Century Sporting Life', St Peters Cooks River History Group website, http://stpeterscooksriverhistory.wordpress.com/2011/10/11/cooks-river-nineteenth-century-sporting-life-2/, viewed 29 November 2012

[19] Joan Lawrence, Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, A Pictorial History of Canterbury Bankstown, Kingsclear Books, Alexandria NSW, 1999, pp 21–22

[20] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History', Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, 2008, p 35

[21] The Singleton Argus, 23 June 1887

[22] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History' in Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Canterbury Council, Canterbury, 2008, p 27

[23] AB Spark, 27 June 1838, in Alexander Brodie Spark diaries, 1 January 1836–22 September 1856, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, A4869

[24] Illustrated Sydney News, 6 June 1889

[25] The Sydney Morning Herald, 27–8 May 1889

[26] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 63

[27] The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 July 1857

[28] The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 October 1862

[29] The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 October 1875

[30] Australian Town and Country Journal, 5 January 1878

[31] Australian Town and Country Journal, 30 March 1878

[32] The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 October 1886

[33] The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser, 18 January 1887

[34] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 59

[35] The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser, 4 August 1887

[36] The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 July 1891

[37] The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 April 1895

[38] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, pp 64–5

[39] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History' in Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Canterbury Council, Canterbury, 2008, p 20

[40] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 65

[41] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 66

[42] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 66

[43] 'Colonial Impact', The Cadigal-Wangal: Aboriginal Marrickville website, http://cadigalwangal.org.au/MenuPages/ColonialImpact.aspx?Id=60, viewed 28 November 2012

[44] 'Cooks River dam', Dictionary of Sydney website, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/structure/cooks_river_dam?zoom_highlight=cooks+river+dam, viewed 9 December, 2013

[45] The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 October 1841

[46] The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 1913

[47] The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 October 1841

[48] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic in Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Canterbury Council, Canterbury, 2008, p 8

[49] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 107

[50] RW Rathbone, 'John Lucas (1818–1902)', Australian Dictionary of Biography online, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University website, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lucas-john-4045, viewed 9 December 2012

[51] The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 February 1883

[52] Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, Canterbury Farm: 200 Years, Canterbury and District Historical Society, Canterbury, 1993, p 9

[53] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, pp 105–7

[54] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 144

[55] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, p 143

[56] Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, Canterbury Farm: 200 Years, Canterbury and District Historical Society, Canterbury, 1993, p 9

[57] Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, Canterbury Farm: 200 Years, Canterbury and District Historical Society, Canterbury, 1993, p 9

[58] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, pp 113–16

[59] Brian Madden and Lesley Muir, Canterbury Farm: 200 Years, Canterbury and District Historical Society, Canterbury, 1993, p 9

[60] Frederick Arthur Larcombe, Change and Challenge: A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, NSW, Canterbury Municipal Council, Australia, 1979, pp 144–45

[61] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History' in Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Canterbury Council, Canterbury, 2008, p 17

[62] Joan Lawrence, Brian Madden, Lesley Muir, A Pictorial History of Canterbury Bankstown, Kingsclear Books, Alexandria, NSW, 1999, p 27

[63] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History' in Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Canterbury Council, Canterbury, 2008, p 31

[64] The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 1913

[65] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History' in Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Canterbury Council, Canterbury, 2008, p 17

[66] The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1868

[67] 'Report from Committee for General Purposes on letters from Mr Holt, from the Agent for the Trustees of the Petersham Estate, and from the executors of the late Mr Despointes, complaining of the pollution of Cooks River, through the operations of a woolwashing establishment near Canterbury, 6 June 1868', reprinted in The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1868

[68] The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 August 1868

[69] The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 August 1868

[70] The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1872

[71] The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 March 1875

[72] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History' in Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Canterbury Council, Canterbury, 2008, p 17

[73] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History' in Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Canterbury Council, Canterbury, 2008, p 17

[74] Noxious and Offensive Trades Inquiry Commission, Report of the Royal Commission, appointed on the 20th November, 1882, to Inquire into the Nature and Operations of, and to Classify Noxious and Offensive Trades, Within the City of Sydney and its Suburbs, and to Report Generally on Such Trades, together with the minutes of evidence and appendices, New South Wales Legislative Assembly, Sydney, 1883

[75] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History' in Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Canterbury Council, Canterbury, 2008, p 19

[76] Cooks River Catchment Management Committee, Cooks River Catchment Management Committee Strategic Plan, City of Canterbury, Canterbury, NSW, 1993

[77] RB Parry, 'Canterbury: An Old Sydney Suburb, Interesting Reminiscences', Evening News, 14 November 1908, p 13

[78] The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 January 1911

[79] The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 August 1913

.