The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

First people of the Cooks River

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The first people of the Cooks River

[media]The Aboriginal name of the Cooks River has not survived but Aboriginal connections to the river run deep, extending far beyond the time when the river flowed as Europeans first came to know it, and continuing long after its banks were dotted with farms. Today many Aboriginal people live in the area and have a strong sense of custodianship of the river and its history and heritage.

The earliest connections

The first Aboriginal people of the Cooks River lived tens of thousands of years ago in a time of cooler temperatures and lower sea levels. [1] Botany Bay did not yet exist, but was instead a huge dune field. The river flowed south through what is now Kurnell and out to sea. [2] Near the current site of Tempe House, traces of a fire and some stone tools from around ten thousand years ago suggest that Aboriginal people lived in this environment. [3] However, most evidence of this earliest river life was buried beneath the waves as sea levels rose and the course of the Cooks River was altered by the formation of Botany Bay and the Kurnell peninsula.

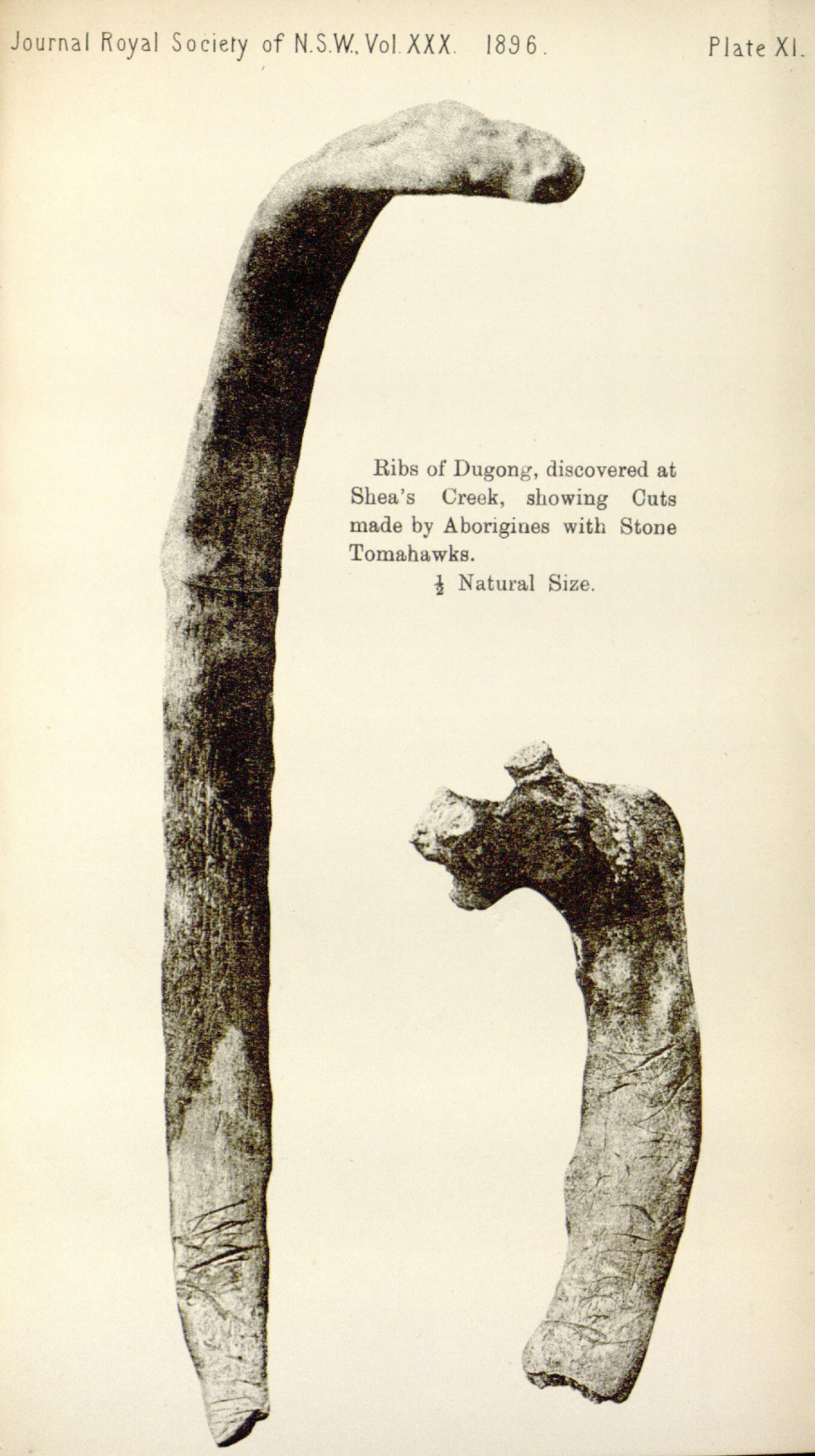

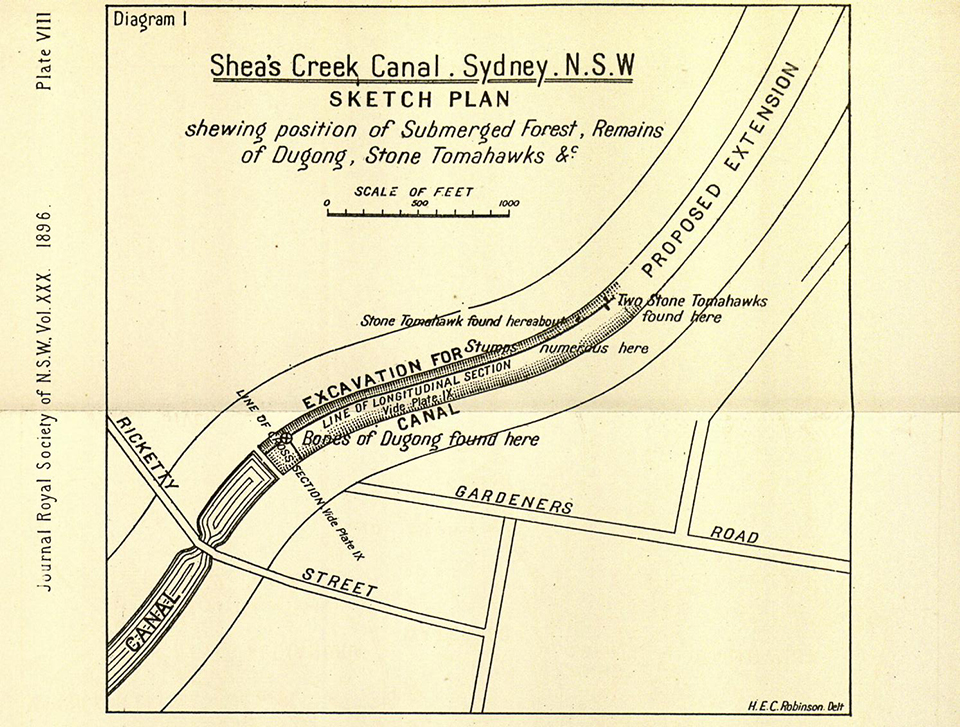

[media]This period of great environmental change, from between eighteen to five thousand years ago, challenged Aboriginal people but also created new opportunities. The butchered bones of a six thousand-year-old dugong were discovered at Beaconsfield during the construction of Alexandra Canal in the 1890s. [4] This find shows that water temperatures were warmer than today and that Aboriginal people were exploiting new resources and environments. Marine life has always been an essential part of the Aboriginal diet along the Cooks River. The grease-spattered stones lining a nine thousand-year-old fire place at Randwick demonstrate that fishing has ancient roots in the area. [5] One of the few surviving shell middens along the Cooks River, at Kendrick Park in Tempe, is filled with the shells of cockles, mud whelks, rock oysters, mud oysters and hairy mussels, as well as fish bones and stone artefacts. [6]

[media]On the river bank near Tempe House, several hundred excavated artefacts show that Aboriginal people along the river also made stone tools. [7] They used a range of types of stone, most of which must have been traded from some distance away. Spear points were among the tools produced, showing that Aboriginal people were hunting land animals as well as fishing. Indeed, the area north of the river around Petersham came to be known to early European settlers as the kangaroo ground. A stone axe from the Kendrick Park midden was likely used to remove bark from trees to make canoes, containers, shields and other resources. Axes were also used to cut toe-holds in tree trunks for climbing to catch possums. [8]

Cultural life

Aboriginal people lived along the Cooks River in groups called bands. These contained men and unmarried women of the clan of the area, and the women married into this group from other clans. [9] Because of this, the structure of bands and their access to areas belonging to other clans was always changing with births, marriages and deaths. It also makes it difficult to be certain about which clan an Aboriginal person belonged to, or what language they spoke. The upper parts of the Cooks River valley seem to have been within the clan lands of the Wanngal people and the lower reaches were either Cadigal or Gameygal lands, or perhaps both. [10] All of these people would have travelled beyond these areas though, and probably spoke several languages.

The cultural beliefs of Sydney's Aboriginal people included an 'All Father' ancestral being. [11] The Sydney landscape was dotted with places of cultural significance and sites of ceremony. A ceremonial ground was located to the south of the river along Wolli Creek at Kingsgrove, and was still being used in the mid nineteenth century. [12] Aboriginal pathways, such as one which crossed the Cooks River nearby at Belfield, may have been related to these important places. [13] Aboriginal art had cultural significance as well as preserving the intimate personal marks of past Aboriginal people. A rock shelter above the river at Earlwood contains 23 white hand stencils as well as two rarely depicted foot stencils. [14] The thick shell midden in the floor of the shelter shows that this was also a popular living space and demonstrates the strong and long term attachment of Aboriginal people to the Cooks River area. When Europeans arrived in 1788 this did not end, and fishing was the activity which appears to have kept Aboriginal people close to the river for many more decades.

Fishing the river

[media]In 1788 'first fleeter', Watkin Tench, observed an Aboriginal village near the Cooks River mouth containing a dozen huts and at least several dozen people. [15] It was almost certainly used for fishing. Soon afterwards, in 1789, smallpox swept through the Sydney Aboriginal population, claiming many lives. How it affected the people of the Cooks River is not known but it did not keep the survivors away from the area. The following year Tench came across another settlement of five huts at the river mouth where fishing spears were found. [16] He also saw Aboriginal man Colebee fishing several hundred metres off the shore in waist deep water. [17]

[media]The purpose of Tench's trip had been to seek retribution for Aboriginal warrior Pemulwuy's spearing of gamekeeper John McIntyre near the Cooks River several days before. [18] Pemulwuy, and later his son Tedbury, carried out raids on European farms in southern and western Sydney in the 1790s and 1800s. These were mostly targeted rather than indiscriminate. For example, in October 1809, Tedbury's gang began to attack travellers near Edward Powell's Half-Way House pub on the Parramatta Road at Homebush. [19] They then stole several dozen of Powell's sheep from his property and drove them south to the Cooks River where they were killed and roasted. [20] The targeting of Powell was unlikely to have been random. He was an original settler at Homebush in the 1790s but had subsequently murdered two Aboriginal boys on the Hawkesbury River. [21] Tedbury's attacks started within weeks of Powell's return to Homebush and this is unlikely to be a coincidence. Powell's past deeds and attitudes would have been well known to Aboriginal people, just as they knew the names and locations of 'friendly' Europeans in their area.

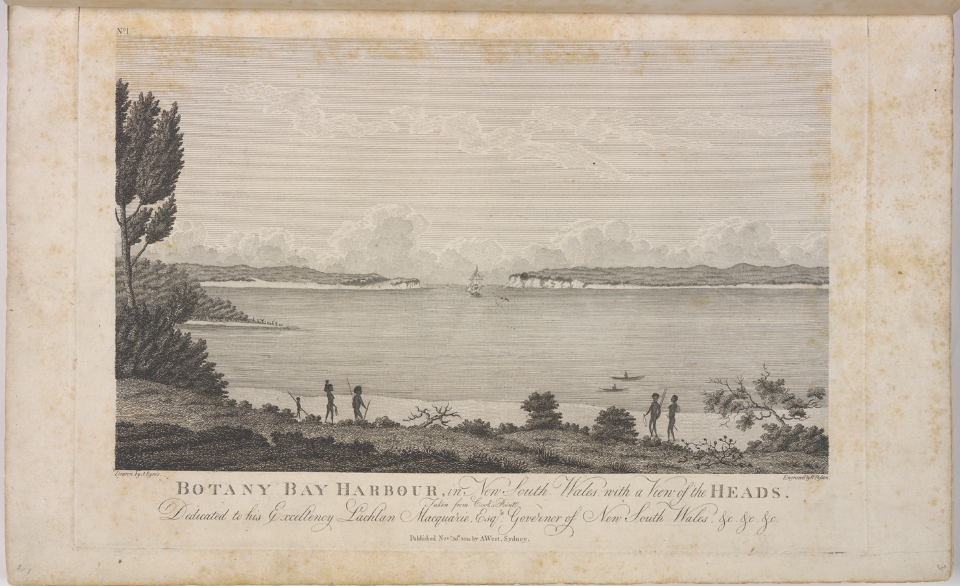

[media]With Tedbury's death the following year, violent conflict appears to have ceased along the Cooks River valley. Although the fertile river flats of the middle portion of the river began to be taken up for farming, there was little European presence along most of the Cooks River for several more decades. Aboriginal people were able to continue fishing the river, as several images from this time show. A picture by Joseph Lycett in 1825 shows an Aboriginal group near the Cooks River mouth fishing in canoes and roasting fish on a fire. [22] Five years later, in the same area, another image by John Thompson shows Aboriginal people by the river with a fishing spear at the ready. [23] These spears were still being used to deadly effect later in the 1830s when an Aboriginal fishing party was observed by James Backhouse and George Walker on the river near what is now Marrickville Golf Course. They speared fish from bark canoes using traditional four-pronged spears and later gathered around a fire to cook their catch. [24]

[media]This group – of three men and two women – was typical of Aboriginal people at the time. They were well known in Sydney town and had travelled from there to the Cooks River that day. [25] One of them had gone to a colonial school and spoke English. They retained old skills and knowledge but lived in a rapidly changing world. It was people like these that are mentioned in passing in historical records as working for European settlers along the river. They may also have been the source of local Aboriginal names, such as the nearby Juhan Munna, or Gum-An-Nan, under the current International Airport terminal. Despite much speculation, the meaning and significance of these names to Aboriginal people has been lost.

Aboriginal people were still fishing the river in the late 1860s, nearly a century after Cook first reconnoitred Botany Bay. In 1868, the Cooks River Aboriginal people had been granted a fishing boat and were continuing a tradition that was thousands of years old. [26] What became of them is not known. Barely a decade later, government policy turned from helping the remaining Aboriginal people around Sydney to survive on their own terms, to actively banishing and segregating them.

Moving away

With the establishment of the Aborigines Protection Board in 1883, Aboriginal people were increasingly confined to government reserves or missions. For the Aboriginal people in southern Sydney, this meant moving to La Perouse on the northern headland of Botany Bay. Residents of a settlement at Botany, south of the Cooks River mouth, were also moved there, as perhaps were any Aboriginal people still living further along the river. From this time there are very few records of Aboriginal people specific to the Cooks River, so it is difficult to state much with certainty. Some Aboriginal people at La Perouse ran commercial fishing operations in the late nineteenth century so it is likely that Aboriginal people continued to fish in the Cooks River at times. [27]

Not all Aboriginal people lived under government and religious control at La Perouse. More independent Aboriginal settlements in the late nineteenth century continued to exist south of the Cooks River at Kogarah and Weeney bays and, in the early twentieth century, along Salt Pan Creek. [28] In the Cooks River area a similar independent settlement was said to have existed near Wolli Creek at Kingsgrove until the 1930s, but no further details are recorded. [29] Individual Aboriginal people were also described living near the river at Canterbury in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. [30] No doubt others also lived in the area, but their stories have yet to be rediscovered.

The whole length of the river was undergoing massive change in the first half of the twentieth century. Its lower reaches were diverted to make way for Sydney airport and the pressure of suburban housing along the upper reaches saw much of the river stabilised behind metal walls or completely channelled along concrete drains. The increasingly polluted river could no longer be used for fishing by anyone.

Returning to the river

[media]After World War II, Aboriginal people began to migrate to the Sydney area in large numbers from country New South Wales and further afield. [31] Marrickville was one of the focal points of this migration, with relatively cheap accommodation close to places of potential employment at Redfern, Alexandria and Botany. Now into their third and fourth generations, the Aboriginal population of the Marrickville, Canterbury and Botany council areas is about 2,500 people and growing. [32] Many live close to the Cooks River and have developed a strong custodial sense for the river, its history and its heritage.

Local community members and the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council have been actively involved in documenting, and protecting, local Aboriginal heritage sites, as well as educating others about Aboriginal culture and history. The midden at Kendrick Park has been protected from further erosion and a commemorative seat has been installed. This allows visitors to reflect on the long history of Aboriginal connections to the river and for Aboriginal people to make new connections of their own.

Notes

[1] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 37–39

[2] AD Albani, PC Rickwood, BD Johnson, and JW Tayton, 'The Ancient River Systems of Botany Bay', Sutherland Shire Studies, vol 8, 1997

[3] Jo McDonald, Archaeological Testing and Salvage Excavation at Discovery Point, Site # 45-6-2737 in the Former Grounds of Tempe House, NSW, Report to Australand Holdings Pty Ltd, 2005

[4] R Etheridge, TW Edgeworth David & JW Grimshaw, 'On the Occurrence of a Submerged Forest, with Remains of the Dugong, at Shea's Creek, near Sydney', Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, vol 30, 1896, pp 158–185; RJ Haworth, RGV Baker and P J Flood, 'A 6000 year old Fossil Dugong from Botany Bay: Inferences about Changes in Sydney's Climate, Sea Levels and Waterways' Australian Geographical Studies, vol 42 no 1, 2004, pp 46–59

[5] M Dallas, D Steele, H Barton, & RVS Wright, 'Randwick Destitute Children's Asylum Cemetery, Archaeological Investigation', vol 2, part 3, Aboriginal Archaeology, Report to South Eastern Sydney Area Health Service, Heritage Council of NSW and NSW Department of Health, 1997

[6] Cadigal-Wangal: Aboriginal Marrickville website, Marickville Council, http://cadigalwangal.org.au/MenuPages/places_midden.aspx?Id=72 , viewed 29 November 2012

[7] Jo McDonald, Archaeological Testing and Salvage Excavation at Discovery Point, Site # 45-6-2737 in the Former Grounds of Tempe House, NSW, Report to Australand Holdings Pty Ltd, 2005, p 36

[8] Val Attenbrow, 'Archaeological evidence of Aboriginal life in Sydney', Dictionary of Sydney website, http://www.dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/archaeological_evidence_of_aboriginal_life_in_sydney#page=9&ref , viewed 29 November 2012

[9] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, p 29

[10] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 22–27

[11] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, p 127

[12] R Hill & B Madden, Kingsgrove: The First Two Hundred Years, Canterbury and District Historical Society, Canterbury, 2004, p 39

[13] Lesley Muir, 'Appendix C: Cooks River Valley Thematic History', Cooks River Integrated Interpretation Strategy, Cooks River Foreshores Working Group, pp3–4

[14] Office of Environment & Heritage State Heritage Register website, Earlwood Aboriginal Art Site, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5060975, viewed 29 November 2012

[15] Watkin Tench and LF Fitzhardinge, Sydney's First Four Years: Being a Reprint of, 'A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay,' and, 'A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson', Angus and Robertson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1961, p 52

[16] Watkin Tench and LF Fitzhardinge, Sydney's First Four Years: Being a Reprint of, 'A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay,' and, 'A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson', Angus and Robertson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1961, p 210

[17] Keith Vincent Smith, 'Colebee', Dictionary of Sydney website, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/colebeeviewed 29 November 2012

[18] Keith Vincent Smith, 'Pemulwuy', Dictionary of Sydney website, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/pemulwuy, viewed 29 November 2012

[19] The Sydney Gazette, 15 October 1809, p 1

[20] The Sydney Gazette, 15 October 1809, p 1

[21] Bob Reece, Aborigines and Colonists: Aborigines and Colonial Society in New South Wales in the 1830s and 1840s, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1974, pp 105–6

[22] Joseph Lycett, 'Botany Bay', ca 1822 in Views in Australia, or, New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land Delineated: In Fifty Views with Descriptive Letter Press, 1824, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1977, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, DGD 1

[23] John Thompson, 'From Mud Bank Botany Bay – Mouth of Cooks River', 1830 in Sketches in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1827–1832, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, DL PXX 31, 2a

[24] James Backhouse, A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies, Hamilton, Adams and Co, London, 1843, p 288; James Backhouse, 'Journal of a Visit to the Australian Colonies, 1831–1841', pp 79–80, in James Backhouse and George Washington Walker papers, 1831-1841, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, B 730–B 732

[25] GW Walker, 'Journal of George Washington Walker, 1831–1841', p 28, in James Backhouse and George Washington Walker papers, 1831-1841, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, B 708–B 728

[26] Currigan, The Humble Petition of Currigan or Captain, an Aboriginal, Hawkesbury River June 6, 1868, NSW, 1868, State Records of New South Wales, Colonial Secretary Letters Received, Box 4/626, 68/2995

[27] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2005, pp 48–9

[28] Heather Goodall and Allison Cadzow, Rivers and Resilience: Aboriginal People on Sydney's Georges River, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2009

[29] Graham Blewett, Re: Salt Pan Creek, Hurstville Historical Society

[30] The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser, 27 October 1891, p 2; The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 January 1931, p 9

[31] George Morgan, Unsettled Places: Aboriginal People and Urbanisation in New South Wales, Wakefield Press, Kent Town, 2006; George Morgan, 'Aboriginal Migration to Sydney Since World War II', Dictionary of Sydney website, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/aboriginal_migration_to_sydney_since_world_war_ii, viewed 29 November 2012

[32] ' 2011 Census Data', Australian Bureau of Statistics Census website, http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/POA2011?opendocument&navpos=220, viewed 5 August 2013

.