The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

George Caleb Hedgeland

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

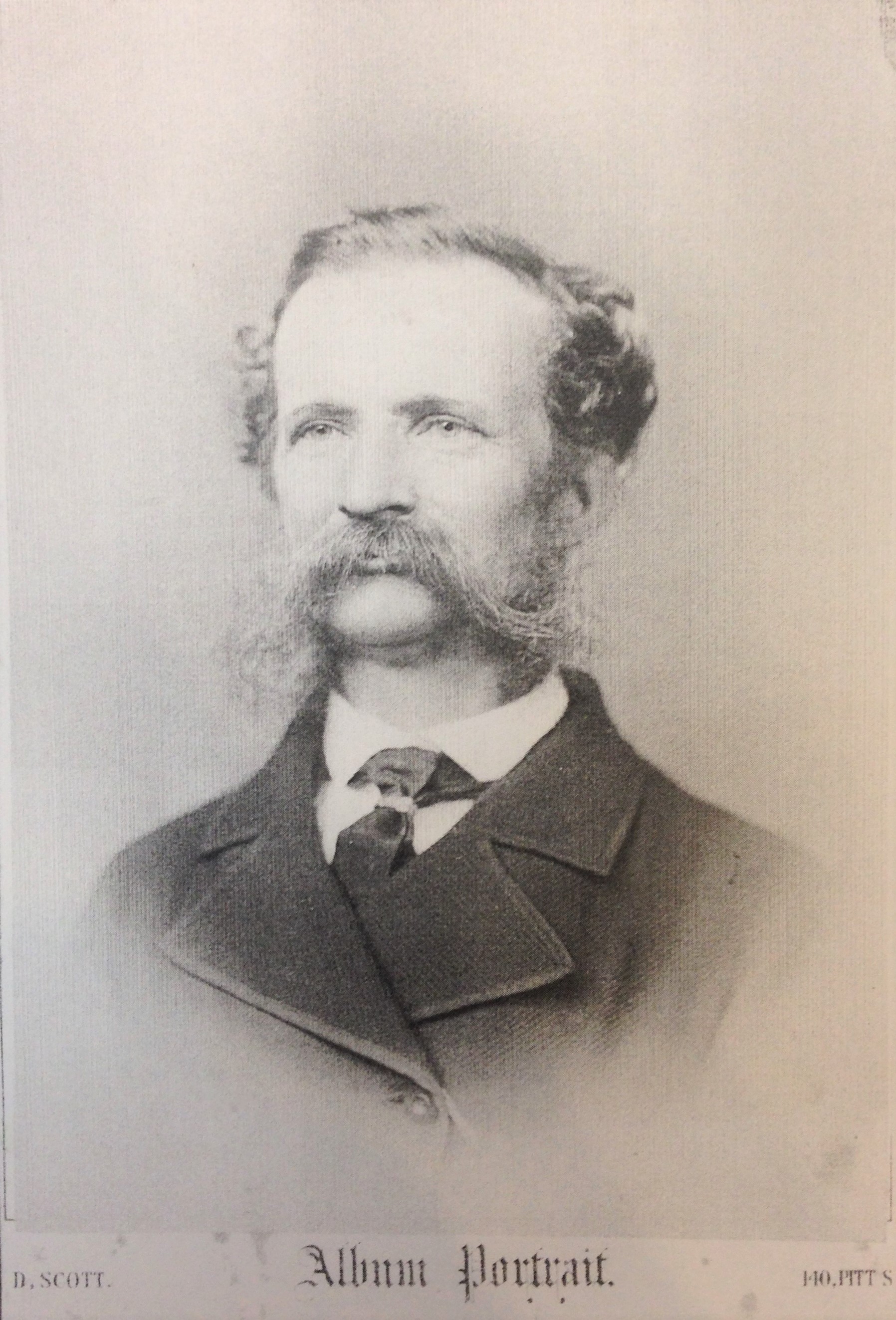

George Caleb Hedgeland

[media]In 1883 journalist REN Twopeny described the working life of Australian colonists:

"The way in which a man changes his trade and occupation is remarkable. One year he is a wine-merchant; the next he deals in soft goods; and the year after he becomes an auctioneer."[1]

George Caleb Hedgeland was just such a colonist as he turned his hand successfully to several different professions during his lifetime.

Early life

Hedgeland was baptised at St Mary’s church, Guildford, Surrey, England on 22 September 1826, the son of John Pike Hedgeland, architect and stained glass artist, and Harriet Hedgeland (née Taylor).[2] He was one of seven children, four of whom survived into adulthood.

Artist/Stained glass artist

In 1845 he was admitted to the Royal Academy of Arts as a painter,[3] though he would not stay for the full 10 years of tuition as in 1851 he entered a piece of stained glass in the Great Exhibition in London that was described as the best piece of English glass there.[4]

Hedgeland became a stained-glass artist at an exciting time. The late 1840s/early 1850s was a period of investigation and experimentation by chemists, glass manufacturers and interested individuals to discover and recreate the qualities of medieval glass. Foremost of these was barrister Charles Winston, Hedgeland’s mentor. When asked for a recommendation to undertake a stained-glass commission, Winston said ‘Hedgeland is your man ... he is the only one who is a true artist … compared to him the rest are a herd of glasswrights’.[5]

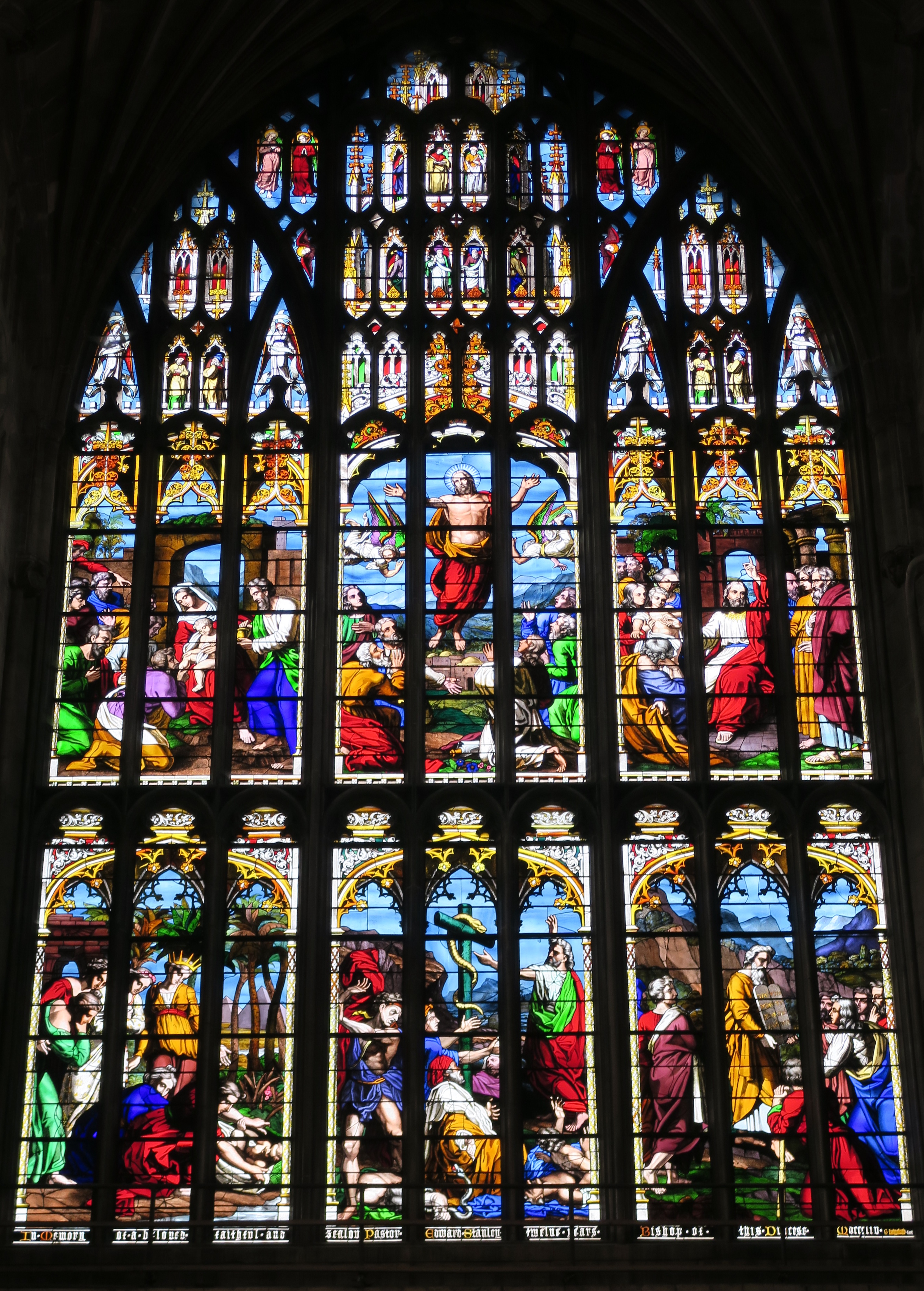

Between 1852 and 1859 Hedgeland designed at least 36 windows in 27 locations in England, including cathedrals, parish churches, university and school chapels, cemetery chapels and benevolent institutions.[6] His most significant work, the great west window of Norwich Cathedral (1854), created controversy with its vibrant colours and naturalistic approach to the human figure.

Pastoralist

In 1859 Hedgeland emigrated to Australia ‘because of his health’.[7] His younger brother James Frederick (known as Frederick), along with family friends from the Henning and Tucker families, had already emigrated. He arrived in Hobson’s Bay (Melbourne) in December 1859,[8] where he joined Frederick before they proceeded to Queensland. There Hedgeland worked with Edmund Biddulph Henning (known as Biddulph) on three of Biddulph’s properties, Marlborough, Exmoor and Lara. He also had an interest in Queensland properties leased in his brother’s name. Hedgeland undertook a variety of duties, from maintaining the station store at Exmoor, to supplying the shepherds located at specific distances from the homestead with the essentials of existence: flour, tea, sugar and meat. Hedgeland was a good horseman and became adept at moving sheep. During 1865 he moved thousands of them from Exmoor to Lara.[9]

Hedgeland and Biddulph’s sister Annie married in 1866 at St Mark’s, Darling Point.[10] The following year their first and only child, Edmund Woodhouse Hedgeland was born, also in Sydney.[11] After each of these events the family returned to Queensland. However, by 1868 Biddulph had relinquished the leases on his properties, and Hedgeland and Annie returned to New South Wales permanently.

Intercolonial exhibition

[media]Hedgeland's former artistic life did come to the fore for a brief time in 1870. In that year there was an Intercolonial Exhibition in Sydney, in a purpose-built building in Prince Alfred Park, near modern day Central Railway Station. There was a Fine Arts division which consisted of a 'competitive' section and a 'non-competitive' section. In the latter Hedgeland exhibited two oil paintings of his English stained glass window designs, one of the Norwich window, the other of his window design for the Church of St Leonard's in Rockingham.[12]

Surveyor

By July 1871 Hedgeland had retrained as a surveyor,[13] his fourth profession after artist, stained glass artist and pastoralist. Between his return from Queensland and his registration as a surveyor, had he tried his hand at his former profession? There is no evidence to suggest this is the case. By the time of Hedgeland’s relocation in 1868, there was only one professional stained glass artist in Sydney, John Falconer from Glasgow, who had opened a studio in Pitt Street in 1863. It was not until 1875 that Frederick Ashwin from Birmingham established himself as the second stained glass artist operating in Sydney.[14] There would have been an opportunity for Hedgeland to establish such a business: perhaps he simply didn't want to.

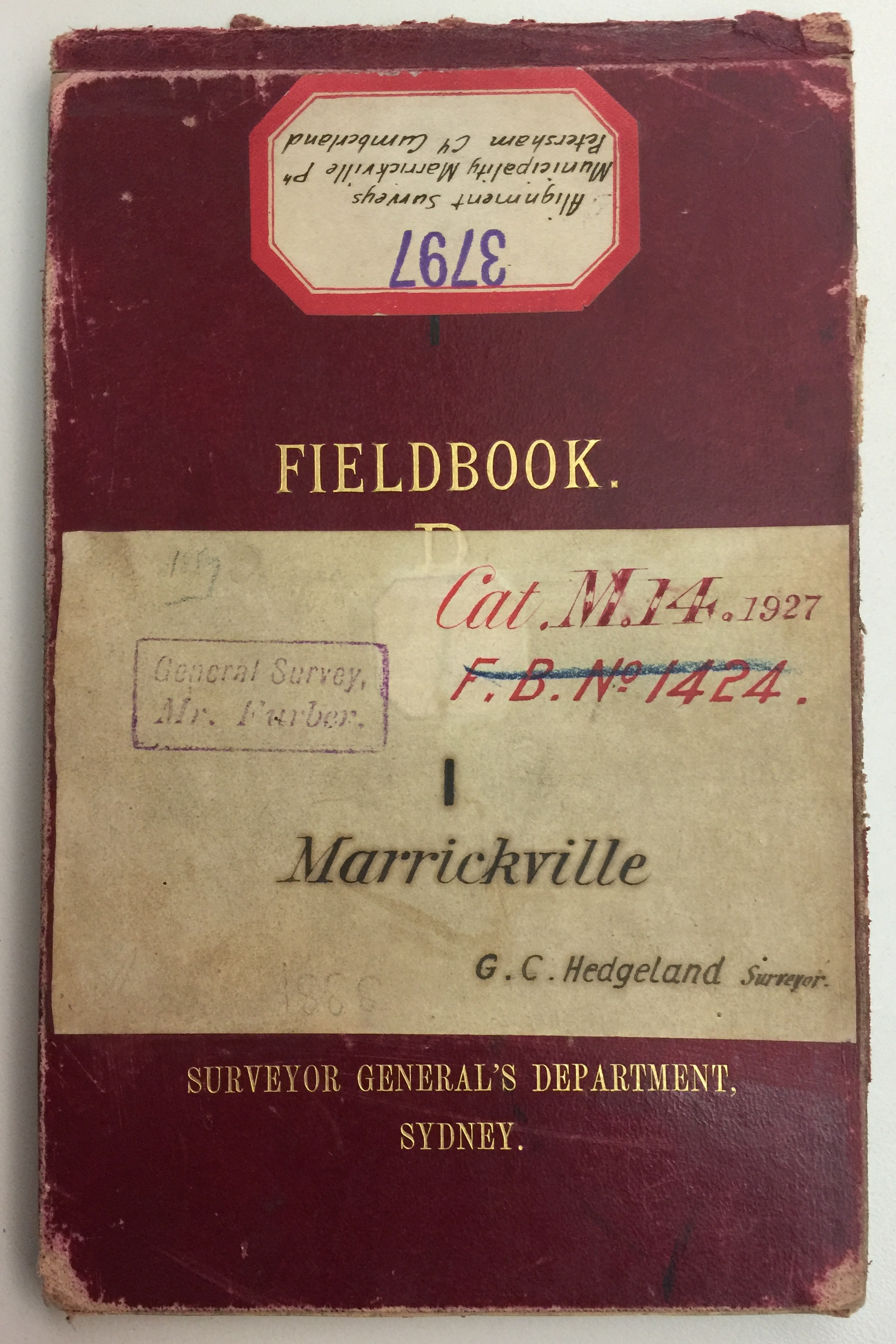

[media]Why did he choose surveying? It could have been because Annie’s relative Lindon Biddulph was a surveyor or because another family friend, George Armytage, was a clerk in the Surveyor-General’s Department. Whatever the reason, his sister-in-law, writer Rachel Taylor (nee Henning) commented frequently in her letters that he was being very well paid.

During his 16 years as a surveyor Hedgeland undertook alignment surveys of streets all across Sydney.[15] This involved the alignment of the major streets in newly created municipalities or re-alignments of individual streets. He worked in the following municipalities and locations: Alexandria, Ashfield, Balmain, Burwood, Leichhardt, Marrickville, Middle Harbour, New South Head Road, Newtown, Paddington, Petersham, Prospect and Sherwood (later Holroyd), Ryde, St Peters, and Waverley, West Botany (later Mascot) and Woollahra. His advice was also sought as to whether roads should be formed, for example, a possible extension to Bonds Road south of Forest Road (now Boundary Road) at Mortdale.

With a small team of men, Hedgeland would conduct a survey, prepare the maps and supervise the insertion of timber alignment posts. Some jobs were short; others took a lot longer. From his first survey of the streets of the Municipality of Ryde until the insertion of the alignment posts, nearly a decade elapsed. Part of this was due to the need for Council to have the funds to acquire the posts and pay for the labour for their insertion. Also, there were often disagreements with landowners who disputed the alignment.[16] One particularly thorny case related to Point Piper Road which formed part of the boundary between the municipalities of Paddington and Woollahra. The claims by the rival councils went as high as the Legislative Assembly.[17] Such disputes were understandable if a comment in Hedgeland’s obituary is to be believed. It stated that his skills not only contributed ‘to the location of old grants and sub-divisions, but were made a means of supplementing the lamentably deficient records of the offices of the Registrar-General’.[18]

Hedgeland’s professional life directly impacted his personal life. Because he wanted to live close to where he worked he and Annie moved often. In his 16 years as a surveyor, they moved house 10 times. This is in addition to the houses they lived in between 1868-1871.[19]

Fruitgrower and later years

[media]Hedgeland retired in 1887[20] and he and Annie moved to Canley Vale where he became a fruitgrower.[21] He was involved with the Anglican Church of St Paul, being part owner of the land on which it was built, and later a churchwarden.[22] Throughout their lives he and Annie were donors to many charitable causes.

In the 1890s Biddulph and his family moved to Ermington Park (now demolished, but it was located in modern day Melrose Park). From 1896 Hedgeland and Annie shared a house Lynwood, in Denistone with Annie’s sister Rachel and her husband Deighton Taylor.[23] It was here, on 28 September 1898, that Hedgeland died from cardiac failure after he had been sick with influenza for three weeks. He was buried in the Field of Mars Cemetery, North Ryde.[24]

After Deighton’s death, Rachel and Annie leased Huaba in Hunters Hill.[25] After the death of Biddulph’s wife, Emily, the three siblings lived together once again, in Passy, also in Hunters Hill. Annie survived her husband by 21 years, dying in 1919, aged 89.[26]

Conclusion

George Hedgeland was truly a man of Sydney. He lived in many of its suburbs and shaped them with his work. He belongs to all of Sydney, not specifically to any part of it.

While it is tantalising to speculate that there may be in a Sydney church an unidentified Hedgeland window, this does not reflect the likelihood that Hedgeland never did stained glass work in Australia. Emigration gave him an opportunity he seized to make a break with the past and to forge a new life and new careers.

Notes

[1] R E N Twopeny, Town Life in Australia, London: Elliot Stock, 1883. Facsimile edition published by Penguin 1973, 193-194

[2] Baptismal register of St Mary’s, Guildford, Surrey available on ancestry.com

[3] Information provided by research assistant from the Royal Academy of Arts Library from admission registers.

[4] Charles Winston, Memoirs Illustrative of the Art of Glass Painting, London: John Murray, 1865,22

[5] Charles Winston, Memoirs Illustrative of the Art of Glass Painting, London: John Murray, 1865,23

[6] This figure is determined by the author’s research using published books, newspapers, websites and personal visits to churches

[7] Dr Alfred Gatty, A Life at One Living, London: Bell & Sons, 1884, 155

[8] Unassisted passenger lists (1852-1923) Record Series VPRS 947. Public Record Office of Victoria. Arrived December,1859; Shipping Intelligence, The Argus 22 December 1859, 4

[9] Details of his work extracted from The Letters of Rachel Henning, Project Gutenberg website http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0607821.txt viewed 29 August 2017. The original letters are held in the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (MLMSS 342/Volumes 1-3 , MLMSS 342/Folder 4X). Edited versions of the letters were serialized in The Bulletin in 1951-1952 with pen drawings by Norman Lindsay; in October 1952 a book, The Letters of Rachel Henning reproducing these edited letters and the original pen drawings was published. There have been multiple subsequent editions. Now it is available as a free download from Project Gutenberg Australia http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0607821.txt and digitized versions of The Bulletin serializations are available on Trove

[10] NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages: marriage registration 1157/1866

[11] NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages: birth registration 3750/1867

[12] Empire, 31 August 1870; Evening News, 31 August 1870

[13] New South Wales Government Gazette, 14 July 1871

[14] Beverley Sherry, Stained glass, Dictionary of Sydney, 2011 http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/stained_glass Viewed 29 August 2017

[15] Details of his career have been determined from his survey field books at NSW State Archives and Records; newspapers; council minutes.

[16] Municipality of Ryde, council minutes 15 April 1877 record that ‘The tracing of the Alignment has been delayed in consequence of several objections lodged against the proposed widening of the Gladesville road causing encroachments on the properties of Dr Brereton, Mrs Frazer and Mrs Hepburn …’

[17] Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly, 19 November 1884

[18] The Surveyor, Vol.11, no.11, 11 November 1898, 274

[19] When they came to Sydney for Edmund’s birth they stayed at Cleveland Cottage in Surry Hills; From 1868-1871: Wimslow (Double Bay/Darling Point); Greenmount (Kirribilli); 1871-1887 Canterbury House (Croydon Park); Mt Vernon (Randwick); Milleewah (Ashfield); Unnamed (Parramatta/DomainHeights); Alverton (Woollahra); Stonyhurst (Paddington); Unnamed (Parramatta/Domain Heights); Chiswick (Woollahra); St Olaves (Bondi); Villette (Bondi)

[20] New South Wales Government Gazette, 10 February 1888

[21] Hall’s Mercantile Agency, Business, Professional and Pastoral Directory of New South Wales for 1895. Sydney: James Best, no date 498. In the profession section under Fruitgrowers Geo. Hedgeland and Edmund Hedgeland, both of Canley Vale are listed.

[22] Torrens title certificate of title volume 928 folio 198 with Frank Paine and William Henry Mackenzie they owned the land which was in September 1914 transferred to the Church of England Property Trust

[23] Sands Directories

[24] New South Wales Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, death registration 11305/1898; Cumberland Argus 8 October 1898

[25] Sands Directories

[26] New South Wales Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, death registration 23816/1919 indexed as Hedgland