The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Immigration

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Immigration

Since its foundation Sydney has been the major port of arrival for immigrants to Australia. There have been times when this position was temporarily lost – the gold rush directed arrivals towards Melbourne in the 1850s and mass migration to Queensland took place in the 1880s. Fremantle was the first port of arrival for many ships, and tired passengers often stopped off there and remained in Western Australia. But the dominance of Sydney was finally consolidated from the 1960s when passengers shifted from ships to planes. Increasing numbers of these were tourist arrivals, a phenomenon almost unknown in the days of shipping.

[media]Settlers arrived in Sydney under various descriptions – as convicts and soldiers until the 1840s, as emigrants leaving the United Kingdom until the 1880s, as immigrants after that and then simply as migrants. Later migrants were often seen as 'foreigners', whereas most immigrants before 1900 were British subjects joining an overseas outpost of other British subjects. Today all those arriving for settlement from overseas are simply known as non-citizens, although special visa concessions are made to New Zealanders.

The population of Sydney has grown since 1788 from less than 1,000 to over four million, or from the size of an English village to more than half the size of London. This growth has been due to three factors – immigration, migration from other parts of Australia, and natural increase. In the early twenty-first century, the growth of Sydney has slowed, with many residents leaving for coastal destinations, while migrants from other parts of New South Wales and from overseas still come into the city. [media]But in the first 50 years, until the end of convict transportation in 1840, arrivals from overseas were the most important force in transforming Sydney from a small village to a substantial city.

Peopling the bush

[media]Many who passed through Sydney in this period settled the inland or formed the base for further growth in what became Queensland and Victoria. Indeed rural pioneers were looked on with more favour than those who remained in the city, an attitude which continued for at least another century. Caroline Chisholm, who cared for female migrants to this overwhelmingly male society, was most insistent those she protected and sponsored should go to the bush.

The stated priorities of organised assisted immigration after 1831 were that rural British and Irish should be recruited, that they should settle on the land, and that enough of them should be female to redress the gross imbalance of the sexes caused by the convict system. But Sydney went on growing nevertheless and by the 1890s the movement of people was back into the city, where most immigrants also remained. That so many convicts and immigrants came from London and its surrounding counties undermined the objective of filling the empty rural spaces. But English and Scottish rural dwellers were also moving into British cities, while the Irish were streaming across the Atlantic to Boston and New York. They were no more likely to appreciate country life when some of them came to Australia.

Migration within the British Empire 1840–1930

[media]When convict transportation to New South Wales ceased in 1840, the colony's population was 127,000, roughly two-thirds of the non-Aboriginal population of the continent. About 45,000 people lived in and around Sydney. This was already the size of a substantial city in England, where only London and a handful of industrial cities exceeded 100,000.

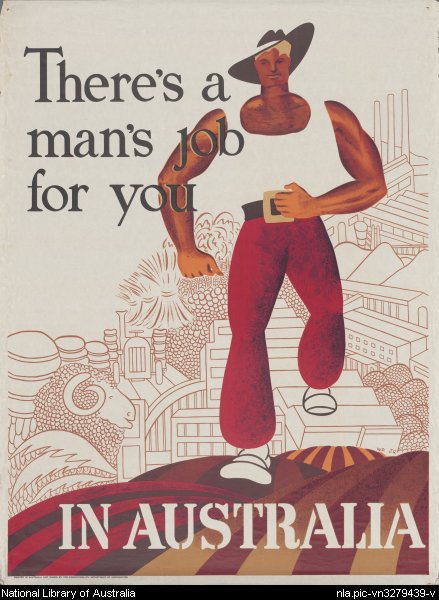

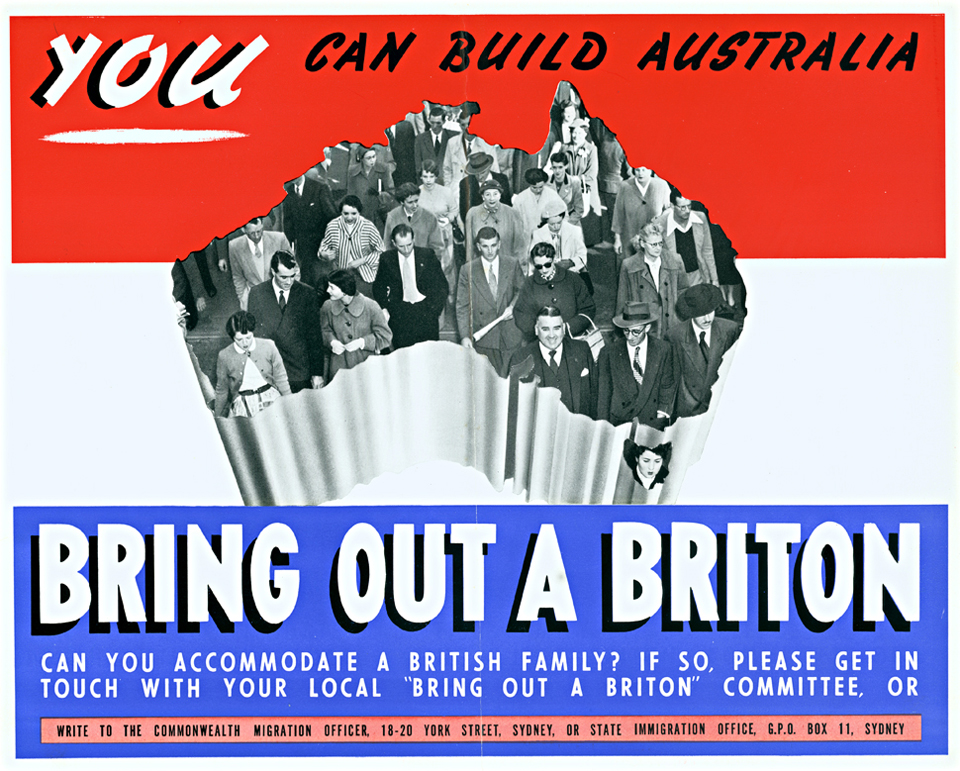

The great majority of immigrants between 1840 and 1930 were British and Irish. This was directly due to the assisted passage schemes which were confined to British subjects, to the distance and expense for others, to deliberate recruitment from Britain by employers, religions and charities, and increasingly to restrictive legislation which discouraged non-British and non-white settlement. This legislation was frequently urged and endorsed by trade unions and the Labor Party, which had increasing political influence from the 1890s.

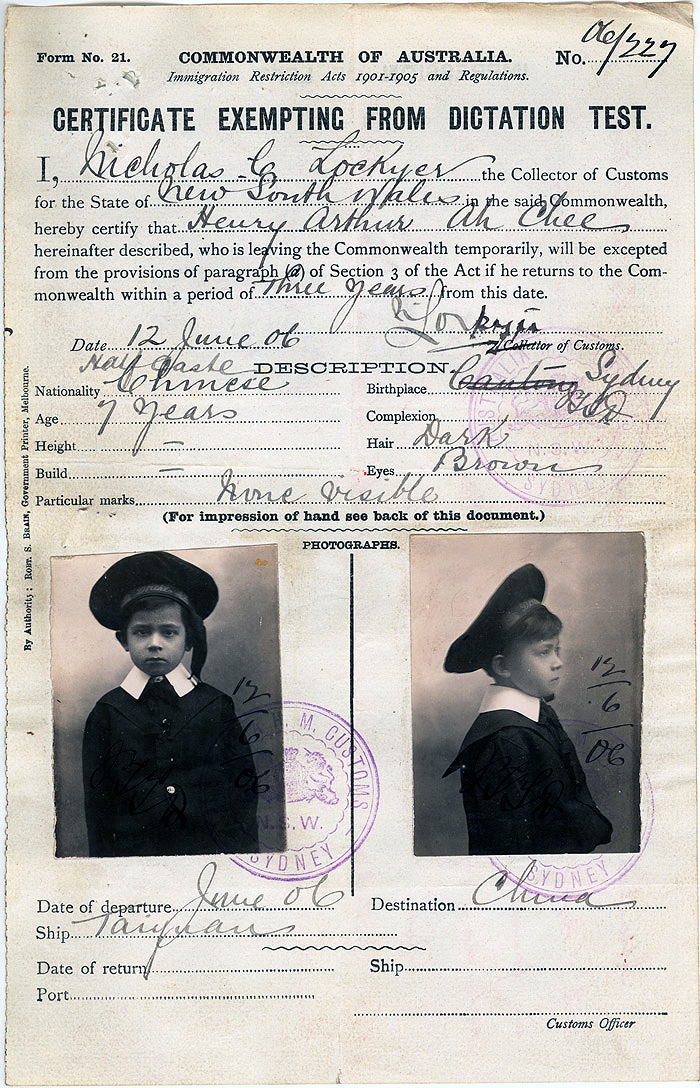

Sydney, as a major Pacific port from the 1840s, attracted business and settlers from the region as well as many seamen and itinerants. Reports from as early as the 1830s noted that 'black' sailors and 'natives of New Zealand' could be seen in Sydney streets. [media]Chinese started to arrive in small numbers from the 1830s. The Jewish community, not all of it British, traces its origins back to the First Fleet and had moved away from its convict origins by 1844, when the first synagogue was built in York Street. But these were small groups among a predominantly British and Irish population, and even the dwindling local Aboriginal population was more numerous.

Non-British immigrants

The growth in numbers of non-British immigrants was slow and marginal with the exception of the Chinese. But the Chinese preferred Victoria, where the 1857 Census shows 25,421 Chinese compared with only 1,806 in the whole of New South Wales, most of them in rural areas. Not until the Victorian depression of the 1890s did Sydney Chinese exceed the number in Melbourne. They were then largely confined to market gardening areas in Rockdale, Botany and Alexandria, although many were engaged in cabinet making and laundries. The Chinese population steadily declined, reaching its lowest point in 1947. The small community around Dixon Street and the markets was sustained by the aging market gardeners. [media]Chinese temples were established from 1898, of which those in Glebe, Alexandria and Waterloo are still in use. The majority of Sydney Chinese in 1900 were market gardeners.

[media]Another non-European group which was to grow substantially during the twentieth century was Lebanese Christians (sometimes called Syrians). Like many Chinese, Jews and Indians they established a base in Sydney, but most of their business was in hawking in rural areas. About 100, mainly Melkite Catholics and Antiochian Orthodox, had settled in Redfern by the 1890s and a Melkite church was opened in Waterloo in 1895. The number of Lebanese had multiplied significantly by 1901, stabilising as a community of about 2,000 in the 1920s.

[media]These small groups were exceptions to the dominance of British subjects and Irish descendants who completely characterised Sydney into the 1930s. The rigid application of the White Australia policy after 1901 prevented the growth of minorities such as Somalis, Chinese or Arabs, unlike in British maritime cities such as Cardiff or Liverpool. British shipping companies continued to staff their ships with people from these countries but trade union vigilance prevented the entry of such sailors into Australian shipping after the maritime strike of 1890.

The exceptions to this picture of declining or tiny marginal groups were the Greeks and Italians, both of which communities saw steady growth from small beginnings until 1940. The majority of Italians settled in rural and provincial areas. They were especially strong on the north Queensland cane fields.

In Sydney, as elsewhere, many opened fruit and vegetable shops. Many Greeks came from the islands and were dedicated to the seafood trade, especially oysters and fish and chips. Both Italians and Greeks ran cafes in country, towns with the Greeks more prominent than the Italians. Many worked at manual and factory jobs, while some Italians became miners. None of these occupations were central to the Sydney economy.

[media]Many Sydney Greeks opened commercial and catering businesses and by the 1940s the majority of families were active in these undertakings. The first Greek Orthodox church was consecrated in Surry Hills in 1895 and a larger church was built in Paddington in 1925. The Greek community was highly organised for its size, with clubs and newspapers as well as churches. The great majority were men, as were the majority of Italians. Greeks and Italians were not as subjected to active prejudice in Sydney as in rural and provincial areas. But apart from some Italian professionals and one or two Labor politicians, they were at the margins of city society. Their social contacts with the British and Irish majority were predominantly as shopkeepers.

The three postwar waves

[media]In 1947 Australia extended free passages to non-British immigrants, of whom the largest number were refugees from communism. The impact of these eastern European 'displaced persons' on Sydney was not as marked as in Melbourne or Adelaide. This immigration wave was soon cut off by the refusal of communist states to allow emigration. [media]The eastern European communities were at their height by 1953 and have passed into their second and third generations of those born locally. In 1971 large numbers of displaced persons and their descendants could be found in Fairfield (Czechoslovaks, Russians, Ukrainians and Yugoslavs), Bankstown (Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Poles), Blacktown (Poles, Yugoslavs, Czechs), and Rockdale (Yugoslavs). These were newly expanding, working-class, western and southern suburbs.

A different pattern emerges for eastern European Jews who were part of this postwar first wave. They settled predominantly in Waverley, Woollahra and Randwick, where they reinforced the existing Jewish population. Germans and Austrians preferred the western suburbs, especially Fairfield, Blacktown and Penrith. The main visible impact of this wave of immigrants was in the availability of European food in shops and cafes and the building of Orthodox churches for the Serbs, Macedonians and Russians. As early as 1971, when the White Australia policy ended, these new areas were already quite cosmopolitan.

[media]Alongside but distinct from this wave was a second wave – the southern Europeans from Italy, Greece and Malta. They came as free immigrants, funding their own journeys and those of their families, who frequently arrived later. As with the eastern Europeans, but for quite different reasons, southern European migration also dropped off by 1971, mainly due to the success of the European Union and favourable changes in United States immigration law in 1965. [media]Favoured areas for the Italians in 1971 were Fairfield, Canterbury, Ashfield, Burwood, Drummoyne, Leichhardt, Liverpool and Bankstown; for Greeks – Canterbury, Marrickville, Rockdale, Botany and Randwick; and for Maltese – Blacktown, Holroyd and Fairfield.

Some parts of Sydney were becoming ethnic strongholds, though scarcely ghettoes as their social conditions were much better than in the traditional inner city slums of the past. Few of these areas had any non-European settlement. For example, Fairfield in 1976 had only 532 people from China, 14 Vietnamese and no Cambodians or Laotians. Nevertheless as areas became more 'ethnic' the British-born started to leave, dropping from 11,000 to 6,000 in Fairfield and from 5,000 to 2,800 in Marrickville between 1971 and 1986, but rising from 9,000 to 13,700 in Penrith and from 5,000 to 10,600 in Campbelltown, at the edge of suburban development.

These two waves of non-British Europeans were both effectively over by 1971. The next wave, which still continues, brought in people who, in most cases, were barred before 1971 on racial grounds. Many of these went to the same suburbs as their European predecessors, such as Fairfield, Marrickville, Bankstown, Canterbury, Strathfield and Parramatta.[media] Some suburbs, such as Auburn, began a rapid process of change. Auburn was the most Muslim city in Australia by 2006.

Refugees

The two largest immigrant groups in the shift away from Europe were from the Middle East and South-East Asia, although Yugoslavia continued to supply immigrants. All three regions were affected by civil wars and consequently many refugees came to Sydney under the federal government's humanitarian program. This had several major consequences – these new migrants could not speak English (which had also been true of many in the European contingents), they were without financial resources, they knew little about Australia except that it was safe, and they were politicised against their previous government or one faction of homeland politics.

Apart from these burdens only the Yugoslavs were white Europeans and many Australians had yet to accept the end of the 'White Australia' policy. These factors led to strongly localised concentrations around migrant hostels, three of which were in Fairfield. Adding to these newcomers were many thousands of Chinese students, who were allowed to remain in Australia after the Beijing repression of 1989, and its dramatic climax in Tiananmen Square. The Middle East produced refugees from Afghanistan, Iraq and Iran. Agitation against these refugees and fear that they would create ghettoes culminated in the rise of the One Nation party in the 1990s and of a Sydney group led by Jim Saleam and eventually renamed Australia First.

Apart from those escaping wars and revolutions, the new wave was added to by Indians, Sri Lankans, Filipinos, Koreans and thousands of students from China and South-East Asia. The University of New South Wales was particularly attractive for them. Whereas many eastern and southern Europeans had preferred Melbourne and Adelaide in the past, by the 1980s Sydney had become the main attraction. This was particularly troubling to then premier Bob Carr who took the unusual position for a state leader that Sydney was 'full up'.

Because immigrant settlement is related to economic capacity, many of this wave settled in the same areas as their European predecessors. Except for some industrialised parts of Botany and Marrickville, most of these places were not in the inner city, which had become gentrified and very expensive. By 2006 the suburb of Auburn was 37 per cent Muslim and 54 per cent of its people were born outside Australia; Cabramatta was 49 per cent Buddhist, 32 per cent were born in Vietnam and 68 per cent were born overseas. [media]These were extreme examples. In the larger municipalities, Fairfield had 17 per cent speaking Vietnamese at home and 27.5 per cent speaking only English; Bankstown had 19.3 per cent speaking Arabic and 43.5 per cent speaking only English; Blacktown had 62.6 per cent speaking only English and 3.6 per cent speaking Filipino Tagalog; and Canterbury had 30.1 per cent speaking only English and 14.4 per cent speaking Arabic. These are multicultural suburbs, not monocultural ghettoes.

As the requirements for immigration have stressed education and professional status, non-Europeans have moved north across the Parramatta River and up the north shore railway line, just as Catholics did before them. Eastwood, Chatswood and Northbridge have become cosmopolitan commercial centres with a growing Asian and Middle Eastern clientele.

The immigrant impact

The immigrant [media]impact on Sydney has several dimensions and varies over time. Obviously Sydney as we know it would not exist if a convict colony had not been planted there in 1788. Equally it would not have developed its 'English' appearance if its population had not been drawn overwhelmingly from the British Isles. Had the French colonised New South Wales – which could easily have happened – buildings, language and lifestyle would have been quite different. The difference would be even greater if the Chinese had settled and created a society, as they did in Singapore, Bangkok or Saigon/Cholon. [media]But British-Australian descendants replaced the British-born by the 1880s, and as they did, they developed distinctive local buildings, institutions and practices. When large numbers of non-British immigrants settled in Sydney from the 1940s, and non-Europeans from the 1970s, they created distinctive enclaves within an overall physical and cultural core that was already long established. These concentrations of Italians, Greeks, Chinese, Lebanese and Vietnamese are sometimes denounced as 'ghettoes', though this term was not applied to the 'Irishtowns' which had developed in the previous century in Surry Hills or Paddington.

The physical inheritance of immigration can be seen in public buildings, especially places of worship, and more recently in shopping precincts redecorated and rebuilt to emphasise a particular cultural background. The early buildings designed by Francis Greenway are still to be found in the city and Parramatta. The mansions of early settlers are still scattered along the southern side of the harbour. Some domestic buildings are preserved in the Rocks, the nearest approximation to a colonial urban precinct – if now cleared of rats and the worst slums. All of these adopted British models, including neo-Gothic churches, two-storey row houses and multi-storey warehouses reminiscent of the London and Liverpool docks.

This tradition of copying British models continued throughout the nineteenth century. Churches built by Anglicans, Catholics, Methodists and Presbyterians were often indistinguishable from the outside if quite different inside. Some Catholic churches adopted Italianate models and some nonconformist chapels were in a classical style. But these, too, were not unknown in Victorian England. They were not distinctively 'Australian'. [media]Domestic architecture, on the other hand, developed a local style – from the balconied rows, to the Federation houses through the Californian bungalow style to the modern 'migrant style' mansions of some of the western suburbs, with their stately entrances, garden fountains and balconies.

Superior central shopping precincts included the arcades favoured in many English and Scottish cities, of which the most prominent is the Queen Victoria Building.[media] But cast iron verandahs to keep off the sun (more recently replaced by cantilevered awnings) were not needed in Britain.

This combination of 'British' public buildings with 'Australian' domestic architecture continued as the typical Sydney mix well into the 1950s. [media]Sydney University looked very much like Oxford University, while Cleveland Street school looked very much like the Board Schools erected in England following the Education Act of 1902. Hospitals, schools, asylums, homes for the aged, art galleries and museums, might all have been transferred from British cities. Even the Sydney Harbour Bridge was built by the Middlesbrough company Dorman Long as a larger version of an existing bridge at Newcastle-on-Tyne. [media]For many years the city ran a double-decker bus fleet of English make and appearance, which most other Australian cities did not. Migration alone does not explain all this, but most Sydneysiders were comfortable with a built environment which did not differ too much from the British original from which they or their recent ancestors had migrated. However they did want more comfortable and spacious houses and gardens and got these from the 1920s.

New forms and influences

The impact of postwar migration on the physical environment was to embed a greater variety of forms within a city which was already well established. A major change came from American and cosmopolitan influences, most apparent in the skyscrapers of the city and North Sydney, but also influential on shopping centres, and later shopping malls, in the new suburbs. Public buildings, such as government and municipal offices and some new churches, also responded to this influence. The same influences were at work in many European and Asian cities.

Direct immigrant influence on the form of the city took three forms: settlement in and improvement of congested and aging properties in the older districts, some of which were previously regarded as slums; settlement in expanding outer suburbs in which immigrant influences on religious and communal buildings was strong; and development of commercial centres with a distinctly ethnic atmosphere. One of the most impressive religious buildings in Sydney is the Gallipoli mosque in Auburn and one of the largest retail centres is the distinctively Vietnamese enclave of Cabramatta.

Immigrant influence was most notable where there was a large and distinctive cultural group. The English remained the largest immigrant group as they had been since 1788, but because they constituted the 'mainstream' for so long their impact tended to be invisible. [media]Most Anglican or Uniting churches were already in place and new ones adopted an international form which was not specifically British. The Irish influence was similarly muted. Catholic churches were not externally distinctive and Irish culture was evident only in some clubs and pubs. New Zealanders, American and other native speakers of English also made very little visible impact, although individuals were often important, as with the British. Thus 'migrant impact' came to mean 'ethnic impact' and was welcomed or condemned depending on personal preferences for variety or uniformity. Sydney eventually passed Melbourne as the 'most multicultural' city in Australia, but has some way to go before becoming the 'most multicultural' city in the world.

References

J Jupp (ed), The Australian people: an encyclopedia of the nation, its people and their origins, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001

J Jupp, Immigration, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1998