The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The murder of Constable Joseph Luker

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Joseph Luker

Convict Joseph Luker placed his past firmly behind him when he decided to pursue a career as a police constable in colonial Sydney. This transition from law breaker to law enforcer would also see him become the first police officer killed in the line of duty in Australia.

Transportation

Luker was born in England around 1770. With his accomplice James Roche, he was apprehended on 23 June 1789 with a heavy load of lead guttering taken from the roof of a house worth about ten shillings.[1] On 8 July 1789 he was sentenced in the Old Bailey to transportation for seven years to New South Wales. He left England on the Atlantic with the Third Fleet and arrived in Australia on 20 August 1791.[2] Declared a free man in 1796, he married a woman named Ann Chapman in Parramatta the following year.[3]

Joining the police

Given his freedom, Luker joined the fledgling police force that had developed from the original night watch established by Governor Arthur Phillip in August 1789.[4] By 1803 it was more formally organised, but it consisted still of only a handful of men, including former convicts, and was responsible for maintaining law and order in a community of approximately 7,000 people.[5]

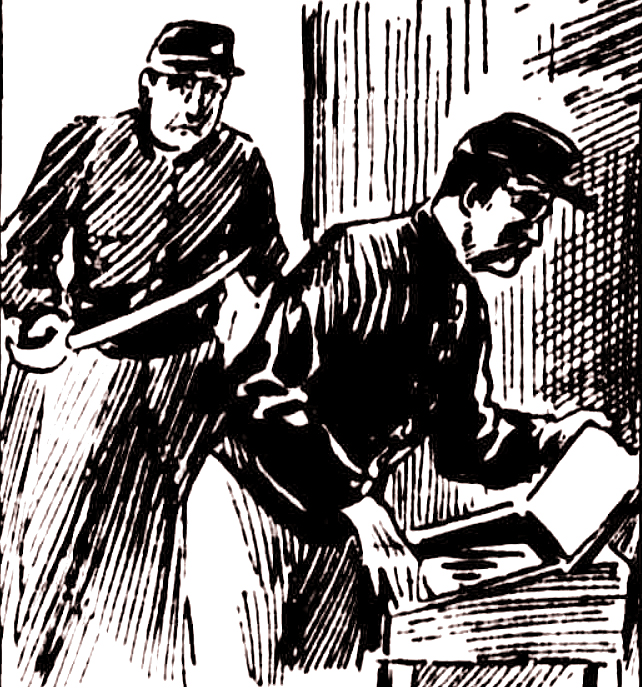

The murder of Constable Luker

[media]On the night of 26 August 1803, between 5 and 8pm, thieves broke into the home of Mary Breeze in Back Row (today’s Phillip Street) and stole a small, portable desk containing documents and money.

Constable Luker was not on duty until midnight but Breeze reported the crime directly to him at his house nearby, rather than to Chief Constable John Redman in the Watch House (perhaps Luker was closer, perhaps Breeze considered him more trustworthy than some of his fellow constables). Luker told her he would look for the desk when on duty, and that he thought he knew who the guilty parties were, and that they would be found at the house of his colleague, Isaac Simmonds.[6]

Luker went in search of the desk after midnight and eventually found it in the scrub on the site behind Back Row that is now occupied by the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. At some point after the discovery, he was set upon by the thieves, and killed in an area that now forms part of the Royal Botanic Gardens, approximately where The Calyx is today. Multiple weapons were used in the brutal attack on Luker including the stolen desk, the frame of a wheelbarrow (which the robbers may have had with them to assist in transporting the stolen desk), his own cutlass and cutlass guard.[7]

His body was discovered just before dawn.[8]

Newspaper coverage

[media]In August 1803 it was only six months since the establishment of Sydney’s first newspaper, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, and the first report of the crime on 28 August 1803 exhibited all the hallmarks of true crime reportage that could be found in equivalent English and American publications of the nineteenth century.[9] The general tone of The Sydney Gazette was usually ‘authoritative and yet filled with deference for all authority, pompous in a stiff, affected 18th century fashion, and mingling a precarious dignity with inappropriate lapses into a humour that is sometimes deplorable’.[10] This style of writing was abandoned with the reportage of Luker’s murder. There was an extraordinary amount of gory detail, as well as an open acknowledgement of a deep-seated fear of crime across all levels of the community. For The Sydney Gazette, a publication still subject to the Governor’s censorship at this time, the writing of Luker’s death was a graphic undertaking:

… The velocity with which the necessary measures of Enquiry were adopted, could only be equalled by the Public Anxiety to discover the Perpetrators of the inhuman act...

On the head of the deceased were counted Sixteen Stabs and Contusions; the left ear was nearly divided; on the left side of the head were four wounds, and several others on the back of it.

The wretch who buried the iron guard of the cutlass in the head of the unfortunate man had seized the weapon by the blade, and levelled the dreadful blow with such fatal force, as to rivet the plate in the Skull, to a depth of more than an inch and a half.[11]

The investigation

[media]There were multiple suspects but no convictions for the murder of Constable Joseph Luker.

The main suspect was Constable Isaac Simmonds (also known as Hikey Bull or Isaacs), another ex-convict who also lived on Back Row and was a known associate of the other suspects. He was charged with wilful murder but found not guilty. Simmonds had been in charge of the stolen desk when it was taken to police and was seen attempting to clean it of blood. Witnesses also testified that one shirt and three hankies, stained with blood, had been found in his house. Despite a career of robbery and violence Simmonds convinced the court that he had a history of nosebleeds and the blood on the shirt was from a fish or a duck.[12]

Another suspect was Constable William Bladders (also known as Hambridge or Ambridge). Bladders, also an ex-convict who had been transported for burglary, was also charged with wilful murder. With the support of witnesses, he was found not guilty, despite Surgeon John Harris stating that he saw blood spatters on Bladders’ legs, feet and hat ‘as if they issued from an artery or vein’, even though he had no cuts or wounds. It was also noted that he had recently put clean shoes on bloodied feet. Bladders had no explanation for these facts until a bystander reminded him that he had slaughtered a pig that morning.[13] Generating more suspicion against Bladders was the discovery of a bloodied barrow in the yard of Sarah Laurence, who lived opposite the premises in which Bladders lodged.[14]

Constable John Russell, yet another ex-convict, was also suspected. He was indicted for breaking and entering but found not guilty due to insufficient evidence.[15]

Joseph Samuels, an ex-convict and professional thief, was also indicted for breaking and entering. Samuels confessed to the robbery of the desk but not to the murder of Luker.

Richard Jackson, another ex-convict and thief, also confessed to robbery and, as a witness for the Crown, implicated Samuels. Jackson was declared innocent of wrongdoing.[16]

Joseph Samuels was found guilty of the robbery, but not of Luker’s murder, and was sentenced to death.

The man they could not hang

On 26 September 1803, Joseph Samuels mounted the hangman’s cart and was transported down High Road (today’s George Street) to the gallows that stood in a paddock at Brickfield Hill. Constable Simmonds, ‘a convicted thief with a known propensity for violence’,[17] continued to attract so much suspicion in relation to the case that he was ‘purposely brought from George’s Head to witness the awful end of the unhappy culprit’ on the day of Samuels’ scheduled execution. His presence at this public display of punishment was a reminder that he only escaped the noose ‘from the want of that full and sufficient evidence which the Law requires’. Samuels and Simmonds were both Jewish and had shared a cell during the trial, during which time, Samuels declared in front of the assembled crowd, they had conversed in Hebrew and Simmonds had sworn to him under oath that he had been discovered by Luker with the desk and had indeed committed the murder.[18]

Astonishingly, three attempts by the executioner to despatch Samuels failed: ‘twice the rope broke, and once it unraveled [sic]’.[19]

The shocking failures of the hangman’s rope saw a groundswell of broad community support and the Provost Marshal, ‘urged by the public clamour’,[20] ‘charged with humanity sped off to his Excellency’s presence to plead for mercy’.[21] ‘An hour later he was back with a reprieve in his pocket’. There was some rejoicing at the site of the gallows as those who had gathered to witness the execution strongly believed that, on this occasion, ‘'the hand of Providence was outstretched' to save the neck of Joseph Samuels’.[22] This belief was confirmed when the broken ropes were tested: each supported a substantial weight without breaking.[23]

Samuels would, however, still be the recipient of punishment when he was transferred first to Risdon Cove in Van Diemen’s Land and then to the notorious settlement at Newcastle to ‘work in appalling conditions in the newly-cut coal mines’.[24] In April 1806 he and seven other convicts attempted to escape in a small boat, but all were assumed drowned in a storm.[25]

As for Simmonds, in October 1803 he was ‘returned to George’s Head, there to be kept at hard labour in the Battery Gang’. It had become clear during the investigation into Luker’s death that he had in his role as a police officer ‘harboured in his dwelling persons of infamous character, and had concealed, encouraged, and connived at their depredations on the Public’.[26] Within a week, he had been given ‘50 lashes in front of the gaol for disorderly conduct, neglect of work, and being refractory’.[27] From here he was eventually transferred to the Newcastle penal settlement. He was released in 1818 and died in Sydney in 1833.[28]

Luker’s burial

Joseph Luker was interred in the old Sydney burial ground, under the site of the modern-day Sydney Town Hall. Horribly, one of his murderers was possibly also one of his pall bearers:

On Sunday last the body of Joseph Luker was very decently interred, a procession following the corpse in which all his Brother Constables assisted, with a number of other inhabitants. The solemnity of the funeral was much heightened by the awful circumstances of his death, and the doubt and anxiety that existed in every mind. The initials of the deceased were on the coffin lid, and his age also, which was 33 years. He was lowered into the grave by four persons belonging to the Watch, one of whom is at present in confinement on suspicion. The deceased was a man of very fair character throughout the Colony, and was a free man a length of time previous to his assassination.[29]

A gravestone was erected later in the year. It stood four feet high and was engraved with a skull and bones, with the addition of a cutlass ‘as by a weapon of that description the skull of the deceased had been most inhumanly fractured’. The epitaph was reproduced in the Sydney Gazette:

Sacred to the Memory of Joseph Luker, Constable;

Assassinated

Aug 19, 1803, Aged 35 Years

Resurrexit in Deo

My midnight’s Vigils are no more,

Cold Sleep and Peace succeed

The Pangs of Death are past and o’er,

My Wounds no longer bleed.

But when my murderers appear

Before Jehovah’s Throne,

Mine will it be to vanquish there

And theirs t’endure alone.[30]

It is unclear whether the date of his death was wrong on the gravestone itself or just in the newspaper's report of the epitaph. Luker's age here also differs from other sources. In 2007 it was confirmed that the remains of Luker had been exhumed and re-interred at Rookwood Cemetery in 1869 when the construction of the Town Hall began.[31]

Constable Joseph Luker’s murder was a ‘catastrophe [that] ingrossed [sic] Public attention’.[32] His death has been cited as Australia’s oldest 'coldest case',[33] and although there were other violent crimes, including murder, committed before 1803 that have gone unresolved, the detailed and very extensive investigation into Luker’s murder certainly distinguishes this case from other cases of early colonial Sydney.

References

Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803, Sydney: In Focus, 2016

Notes

[1] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803. (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), p3; The National Archives UK online currency converter estimates this amount to be worth approximately the same amount as three days wages for a skilled tradesman, National Archives UK Currency Converter: 1270-2017 website http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/ viewed 20 June 2019

[2] Convict Records, Joseph Lucar, Convict Records of the Home Office. (Brisbane: An Online Project of the State Library of Queensland, n.d.), http://onesearch.slq.qld.gov.au/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=slq_alma21116233100002061&context=L&vid=SLQ&search_scope=FHCOMBINED&tab=fhcombined&lang=en_US viewed 10 September 2018

[3] Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Joseph Looker and Ann Chapman 1797 Marriages. (Sydney: Justice, New South Wales Government, n.d)

[4] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803. (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), p2

[5] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Historical Population Statistics. Table 1.1 Population by Sex, States and Territories, 31 December 1788 Onwards. (Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, n.d.), http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/INotes/3105.0.65.0012008Data%20Cubes?opendocument&TabName=Notes&ProdNo=3105.0.65.001&Issue=2008 viewed 19 November 2016

[6] Third Day, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales 25 September 1803, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625790 viewed June 14, 2019

[7] Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803. (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), pp5-7; Murder, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 28 August 1803, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625757 viewed 13 June 2019

[8] David Dickinson Mann, The present picture of New South Wales, 1811 (Sydney: John Ferguson [1811]1979), p11 ‘I was the second person at the spot, where the body of the unfortunate man was discovered; and, in attempting to turn the corpse, my fore-finger penetrated through a hole in the skull, into the brains of the deceased.’

[9] Murder, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 28 August 1803, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625757 viewed 13 June 2019

[10] H.M. Green, George Howe – Australia’s First Newspaper. The Sydney Morning Herald 11 April 1935, p10 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28017881 viewed 10 June 2019

[11] Murder, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 28 August 1803, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625757 viewed 13 June 2019

[12] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803. (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), pp16-17

[13] George F.J. Bergman, The Story of Two Jewish Convicts: Joseph Samuel, ‘The Man They Couldn’t Hang’ and Isaac Simmons, Alias ‘Hickey Bull’, Highwayman and Constable Journal of the Australian Jewish Historical Society 1963 5 (7), pp320-331

[14] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803. (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), pp5-7; Murder, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 28 August 1803, pp15, 31

[15] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803. (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), p17

[16] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803. (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), p10

[17] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803 (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), p16

[18] Sydney, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 2 October 1803, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625802 viewed 1 June 2019

[19] Geoffrey Scott, The Man They Couldn’t Hang Herald Saturday Magazine 26 September 1953, p7 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27523294 viewed 1 June 2019

[20] Geoffrey Scott, The Man They Couldn’t Hang Herald Saturday Magazine 26 September 1953, p7 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27523294 viewed 1 June 2019

[21] ‘WRS’, A Story of 1803: The Man They Could Not Hang The Sydney Morning Herald 23 May 1931, p9 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16780083 viewed 1 June 2019

[22] Geoffrey Scott, The Man They Couldn’t Hang Herald Saturday Magazine 26 September 1953, p7 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article27523294 viewed 1 June 2019

[23] Alan Sharpe, Crimes that Shocked Australia. (Milsons Point: Currawong, 1982), p12

[24] Alan Sharpe, Crimes that Shocked Australia. (Milsons Point: Currawong, 1982), p12; John Levi, These are the Names: Jewish Lives in Australia 1788-1850 (Melbourne: Meigunyah Press, 2016) pp738-139

[25] George F.J. Bergman, The Story of Two Jewish Convicts: Joseph Samuel, ‘The Man They Couldn’t Hang’ and Isaac Simmons, Alias ‘Hickey Bull’, Highwayman and Constable Journal of the Australian Jewish Historical Society 1963 5 (7), p330

[26] Isaac Simmonds, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 2 October 1803, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page5775 viewed 14 June 2019

[27] Isaac Simmonds, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 9 October 1803, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625820 viewed 14 June 2019

[28] John Levi, These are the Names: Jewish Lives in Australia 1788-1850 (Melbourne: Meigunyah Press, 2016) pp749-750

[29] Re-examinations, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales 4 September 1803, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625760 viewed June 14, 2019

[30] Resurrexit in Deo The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 6 November 1803, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625862 viewed 4 June 2019

[31] Gemma Jones, Mystery Solved in Time for Police Remembrance Day The Daily Telegraph 28 September 2007, Daily Telegraph website http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/grave-story-of-first-fallen-cop/news-story/d98292dc65594dce0901099d1f849576 viewed 6 April 2017

[32] A Grave-Stone, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 6 November 1803, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article625860 viewed 13 June 2019

[33] Louise Steding, Death on Night Watch: Constable Joseph Looker, 1803. (Sydney: In Focus, 2016), p4