The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The wreck of the Edward Lombe

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The wreck of the Edward Lombe

[media]In August 1834 one of the worst maritime disasters in Sydney waters took place when the Edward Lombe was wrecked on Middle Head. The story has been overshadowed by the catastrophic wreck of the Dunbar in 1857, but at the time the wreck of the Edward Lombe was a significant and distressing event for the colony. Never before had the colony witnessed the destruction of a large sailing vessel with a resulting loss of life[1] and it generated widespread debate about the safety of shipping in the harbour.

The Edward Lombe

[media]The Edward Lombe was a three-masted timber barque of 347 (imperial) tons (352.6 tonnes) that had been built in Yorkshire in 1828. The ship had made earlier voyages to Australia in 1830 and 1832-3, carrying convicts, free passengers and cargo under the command of Captain Whiteman Freeman, and in March 1834 she sailed again for New South Wales from Portsmouth under Captain Stuart Stroyan.[2]

[media]Her first port of call in Australia was Hobart on 21 July, where some passengers disembarked and others joined the vessel.[3] The ship departed for Sydney on 15 August 1834 with a general cargo of spirits, salt and other merchandise, and a new commission to sail to Mauritius to collect a shipment of sugar. There were 22 crew and 7 passengers aboard, including one woman, a Mrs Jones, who was travelling from England with her husband and her brother.[4]

Shipwrecked

[media]Conditions at sea were appalling as the Edward Lombe approached the entrance to Port Jackson during the late afternoon and evening of Monday 25 August. The coast was in the grip of a gale, seas were high, and visibility was very poor. Captain Stroyan planned to ride out the storm at sea and return in daylight, when visibility would be better and conditions hopefully improved. However it was not to be:

About eight o'clock at night, they carried away their fore-top-mast stay-sail, and fore-top-mast back-stay; and about the same time saw the light from South Head. Captain Stroyan now found it impossible to keep the vessel off the Coast, and steered for the Heads, which they entered somewhere about half-past nine o’clock. The wind continuing to blow with the greatest fury, and no pilot being on board, [the captain] thought it advisable to let go an anchor within about two ships’ length of the Sow and Pigs; this anchor is supposed to have parted from the cable immediately, such was the violence of the gale, and another was let go, but which only checked the course of the vessel for a few minutes, and she commenced drifting. The Edward Lombe was almost immediately afterwards dashed stern first upon the bold rocks called the Middle Head...[5]

The ship was doomed. Passengers below deck were wakened, with the crew particularly concerned for the well-being of the female passenger Mrs Jones. She and her husband were roused from their beds and brought on deck for their safety, but Mr Jones was swept overboard by the high seas. Another passenger, Austin Knight, refused to come up on deck, and was never seen again.

At this time the seamen and passengers were running about the ship panic struck, some in the shrouds, and others in different parts of the vessel. The Captain and two seamen with a passenger named Wilkinson, were engaged in cutting away the launch, for the purpose of endeavouring to save all hands, when a tremendous sea came and swept away Captain Stroyan, and the three other persons, boat and all...[6]

The barque broke apart, with only the stern remaining, wedged on the rocks. The survivors huddled there, with Mrs Jones in the centre for her protection, swept by powerful waves all night. Two more men were drowned as they attempted to cast a line to the shore from the stern, while another was dashed on the rocks but was miraculously thrown by the waves onto the bows of the wreckage and climbed onto a high rock, which he managed to cling to all night.

Rescue

[media]After daybreak the wreck was spotted by a local sailor, Captain Swan, who summoned the Watsons Bay pilots. Unable to approach due to the high seas, Swan moored his cutter, Venus, in the neighbouring cove. At great risk to themselves, he and his crew climbed over the rocks to reach the survivors and help them from the wreckage. One in particular, a convict (also coincidentally named Jones), took such great risks that the survivors later petitioned the Governor on his behalf.

Most reports of the disaster said 12 of the 29 people on board had died, but coverage that includes the names of all on board lists 11 dead and 18 survivors.[7]

Five crew were among the dead, and six of the passengers.

The crew members were Captain Stuart Stroyan; George Norman, the second mate; William Tebbutt , third mate; James Starkey (or Starkie), seaman, and Richard Cressy, seaman.

The unfortunate passengers were Thomas Gibbs; Francis Jones; Charles Kemp; Thomas Greenhill; William Wilkinson and Austin Knight.

The survivors included several boys who were in the ship's crew and the only woman. The crew who survived were the first mate Thomas Marshall; Henry Lawson, carpenter; Andrew Anderson; Joseph Terrence; Henry Sutherland; Richard Young; Thomas Lake; William Wilson; Edward Bryant; Thomas Lang; Robert Pratt; John Howlett; Thomas Taylor and three boys, Henry Weatherhead (the Captain’s nephew), Henry Younghusband and William Cranston.

The two surviving passengers were Mrs Jones and another boy, Henry Tebbutt, who was the young brother of the third mate.[8]

Aftermath

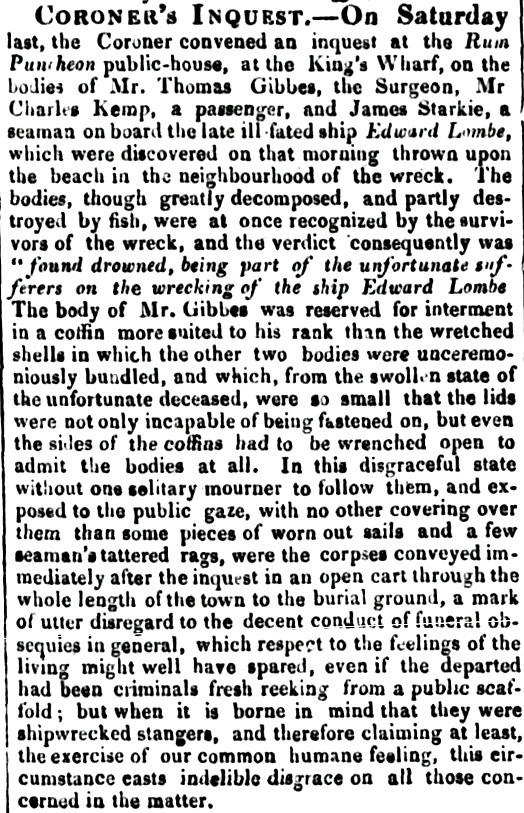

[media]It was several days before any of the bodies were recovered, and Sydney's residents were appalled at the treatment some of the remains received. After the first coronial inquest, in which the remains of passenger Charles Kemp and seaman James Starkie were identified, their bodies were 'unceremoniously bundled' into two 'wretched shells' rather than coffins, that:

from the swollen state of the unfortunate deceased, were so small that the lids were not only incapable of being fastened on, but even the sides of the coffins had to be wrenched open to admit the bodies at all. In this disgraceful state without on a solitary mourner to follow them, and ex-posed to the public gaze, with no other covering over them than some pieces of worn out sails and a few seaman's tattered rags, were the corpses conveyed immediately after the inquest in an open cart through the whole length of the town to the burial ground.[9]

This was a ‘mark of utter disregard’ to ‘decent conduct’:

even if the departed had been criminal fresh reeking from a public scaffold; but when it is borne in mind that they were shipwrecked strangers, and therefore claiming at least, the exercise of our common humane feeling, this circumstance casts indelible disgrace on all those concerned in the matter.[10]

JB Montefiore, the Sydney shipping agent responsible for the vessel, ensured that the recovered remains of other victims were handled more respectfully.

After the bodies had spent several days in the water it was difficult to make positive identifications, and a series of gruesome inquests were carried out in hotels throughout the city. Francis Jones was identified from black hair and a worsted stocking that was still on his skeletal remains,[11] while the remains of sailor Richard Cressey were in a ‘most frightful spectacle of decomposition: the eyes also were picked out, and other parts of the features eaten off by fish’.[12]

Wreckage and salvage from the ship was found strewn around the harbour. Among the goods salvaged were several casks of brandy, ale and a spirit known as Geneva, 19 casks of salt, two kegs of herrings, a tea caddy and three pairs of shoes.[13] The captain’s desk, and several packets of mail were also found.[14] The wreck of the ship itself was eventually sold to local shipbuilder, HT Bass, for 85 pounds.[15]

[media]A charitable fund was set up to support the survivors, and various benefits, theatrical events and church services were held throughout the city. Mrs Jones, who had lost both her husband and her brother in the wreck, was offered particular support by the colony before her return to England in October,[16] as was Henry Weatherhead, the young nephew of Captain Stroyan who was sent to the school of Mr Trood, where the other students took up a collection for him.[17]

A floating light ship

[media]Although the colony had acted quickly to support the survivors, there were some complaints about how the authorities responded to the disaster.

After the rescue it was suggested that the pilots at South Head should have responded more rapidly, but the surviving officer of the ship, Thomas Marshall, wrote: ‘owing to the darkness of the night, and the heavy rain that fell, it was impossible for any one to see the ship when she came into harbour, and if they had, the gale was so strong, that no boat could have got alongside, to render the least assistance.’[18]

The wreck lent weight to an argument for a permanent light on the Sow and Pigs reef, the shoal of rocks just inside the harbour entrance, as it would have helped better guide the ship:

The present catastrophe will now convince the Government that a beacon, instead of a tar barrel, ought to be in place on the Sow and Pigs.[19]

The jurors at the Coroner’s inquest on the body of seaman Richard Cressy on 3 September included ‘several master mariners’ and they also included in their report a recommendation to the Government that a beacon be ‘as speedily as possible erected on the breakers called the ‘Sow and Pigs’’.[20]

A letter from Francis Greenway about proposals he claimed to have made in 1814 for navigational aids for the harbour also appeared in The Sydney Gazette,[21] including, as a priority, the placement of a beacon light at the Sow and Pigs, but that he had been ‘overruled’ on these matters.[22]

[media]By 1836, a permanent floating light ship had finally been placed at the Sow and Pigs to mark the rocks and to serve as a guide to navigation, and had proved so useful that at least one newspaper expressed the hope that it might soon be superseded by a small lighthouse.[23] In 1912 the light ship was replaced by a buoy with a gas light,[24] that was in turn replaced by the Western Channel Pile Light.[25]

The site

There is no memorial to mark the site of the wreck of the Edward Lombe, but in 1993 the NSW Heritage Office determined the location by comparing drawings and paintings done at the time with existing landmarks.

[media]Most of the wreckage had been salvaged at the time of the disaster and an investigation of the site in 2006 found little evidence of the wreck, apart from two anchors of the right period that were found near the Sow and Pigs Reef and Middle Head at locations that aligned with the published accounts of the disaster.[26]

References

Shipwrecks of the South Head region, April 2003,Woollahra Library Local History Centre, Information Sheet 5, http://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/16492/Shpwrks-Sth-Hd_region_sht5-layout.pdf viewed 2 May 2009

Shipwreck Edward Lombe, Australian National Shipwreck Database, website: https://dmzapp17p.ris.environment.gov.au/shipwreck/public/wreck/wreck.do?key=539 viewed 2 May 2009

Edward Lombe Wreck Inspection Report, Heritage Office of NSW, prepared by Tim Smith and David Nutley, June 2006: http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/heritagebranch/maritime/EdwardLombeReport.pdf viewed 2 May 2009

Notes

[1] Edward Lombe Wreck Inspection Report, Heritage Office of NSW, prepared by Tim Smith and David Nutley, June 2006: http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/heritagebranch/maritime/EdwardLombeReport.pdf

[2] Omniana, The Sydney Herald, 2 May 1831, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12842983; The Edward Lombe, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 8 January 1833, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2210249; Shipping Intelligence, The Sydney Monitor, 9 January 1833, p 3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32142863; For London Direct, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 23 February 1833, p1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2210898; Shipping Intelligence, Hampshire Advertiser & Salisbury Guardian, 29 March 1834, p3

[3] Van Diemen’s Land News, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 August 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12850190; Passenger Arrivals, 1829-1957 Reports of ships arrivals with lists of passengers 1834 July. p8, Selected Immigration Books from the Archive Office of Tasmania, Archives Office of Tasmania, via Ancestry online database

[4] Domestic Intelligence, The Sydney Herald, 1 September 1834, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12850332 It is unclear which of the other passengers (or crew members) was Mrs Jones' unfortunate brother.

[5] Ship News: Wreck of the Edward Lombe, The Sydney Herald, 28 August 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12850290

[6] Ship News: Wreck of the Edward Lombe, The Sydney Herald, 28 August 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12850290

[7] THE PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY, The Sydney Monitor, 3 September 1834, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32147077; Shipwreck inside the Heads, Sydney Monitor, 27 August 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32147040; Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 28 August 1834, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2216955; Wreck of the 'Edward Lombe', Sydney Herald, 28 August 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12850290; FURTHER PARTICULARS RESPECTING THE LOSS OF THE Edward Lombe, The Sydney Monitor, 30 August 1834, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32147060

[8] Administration of Justice, Sydney Morning Herald, 2 March 1874, p3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page1448886

[9] Coroner's Inquests, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 9 September 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page501299

[10] Coroner's Inquests, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 9 September 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page501299

[11] Coroner's Inquests, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 9 September 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page501299; Original Correspondence, Sydney Times, 12 September 1834, p3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article252811571; Coroner's Inquests, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 11 September 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2217051

[12] Coroner’s Inquest, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 4 September 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2217009

[13] Advertising, The Sydney Herald, 15 September 1834, p1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12850450

[14] Wreck of the Edward Lombe, The Sydney Monitor, 30 August 1834, p4 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32147058

[15] Shipping Intelligence, The Sydney Monitor, 3 September 1834, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32147094

[16] Whaling News, The Sydney Herald, 9 October 1834, p3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12850652; The Beauty of the City Road, Sydney Monitor, 30 January 1836, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32150632; Although Mrs Jones and Thomas Marshall both thanked the people of Sydney for their generousity, it is unclear if Mrs Stroyan, the Captain's widow, ever received any financial support , EDWARD LOMBE.The Sydney Herald, 27 July 1835, p2,3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12852748

[17] Juvenile Sympathy, The Sydney Herald (Supplement), 8 September 1834, p1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12850375

[18] Edward Lombe, The Sydney Herald, Monday 22 September 1834, p1

[19] Shipwreck, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 28 August 1834, p3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2216955

[20] Coroner’s Inquest, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 4 September 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2217009

[21] To the Editor of the Sydney Gazette, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 13 September 1834, p2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2217079

[22] Alasdair McGregor, A Forger’s Progress, Sydney: NewSouth Books, 2014

[23] Notice to Mariners, New South Wales Government Gazette, 31 August 1836, p665, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article230673039; The 'Ceres' Steam Packer, The Sydney Times, 3 September 1836, p3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article252811454

[24] Notice to Mariners, Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales, 22 November 1911, p6214, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article226917872

[25] Harbor Mystery, Evening News, 29 February 1924, p8, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article119192132

[26] Edward Lombe Wreck Inspection Report, Heritage Office of NSW, prepared by Tim Smith and David Nutley, June 2006, p10, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/resources/heritagebranch/maritime/EdwardLombeReport.pdf