The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Aboriginal People on Sydney's Georges River from 1820

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Aboriginal People on Sydney's Georges River from 1820

Aboriginal people were the traditional owners of the lands on both sides of the Georges River when the Europeans arrived, Dharug on the northern shore, Dharawal on the southern. Of all the tributary creeks and the river itself, the only Aboriginal name that survives is Guragurang (now Mill Creek). Aboriginal owners had always interacted with the river lands, which is why there are campsites, middens and artworks all along the river's length. The river forced the new settlers to farm in some areas but not others, and the varied ways of using the land and river led to different histories and stories for Aboriginal people along the river.

There is a great deal of writing about Aboriginal people as they defended their rights to land, water and their resources in the early days of the invasion. However, once these initial battles had been lost, it seems as if Aboriginal people simply 'melted away'. Sometimes they are thought to have been removed by governments by being 'rounded up' onto missions and reserves. It was certainly very convenient for settlers to feel that Aboriginal people had gone 'somewhere else' or had mysteriously died. But Aboriginal people had learned a great deal about Europeans in the first days of violence and conflict. One lesson was caution – to be seen only when they wanted to be seen.

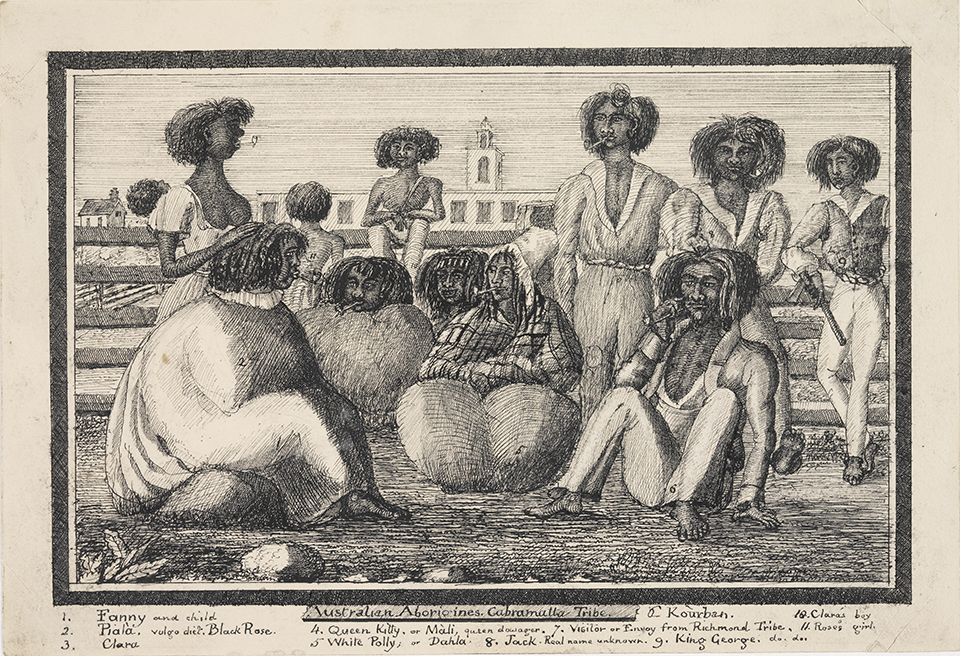

Aboriginal people [media]survived and found ways to maintain connections with country and make a living. The Colony, Grace Karskens' study of Sydney in the first 30 years of settlement, [1] and the work of Keith Vincent Smith, shows that Aboriginal people continued to live in significant numbers around Port Jackson. Our detailed study of the following decades on the Georges River in Sydney's south west, Rivers and Resilience, [2] has shown that Aboriginal people along the river had a range of different strategies for keeping in touch with their country.

There are many Aboriginal stories about the Georges River – these are just a few. Aboriginal organisations along the river are working to gather these stories to add to the rich growing Aboriginal histories of the river – right up to today.

Safe refuges – Jonathon Goggey and Voyager Point

One strategy was to find safe refuges. This happened in Sydney and other areas after the 1820s, such as on the north coast and riverine western slopes. Aboriginal people moved around country to avoid danger, but they did not move away from it. They found refuge in secluded areas of the hills and valleys, or by working in areas and industries where their labour was sought. [3]

Kogi is well known as one of the Dharawal men who tried to negotiate with settlers in the first days of the British invasion, but was also an associate of Pemulwuy and involved in the resistance. After the initial conflict, he seems to have lived on land now known as Voyager Point, near where Harris and Williams creeks join the Georges River. In 1857, a white neighbour tried to push Kogi's grandson, Jonathon Goggey and his family, off the land. Jonathon Goggey wrote a petition to the Governor demanding the return of the land because his family had lived on it for so long. He made it clear this was not a personal claim but one for the family and community.

It seems that Goggey won this battle, even though there was no written statement or legal decision to that effect. The land was not subsequently ‘improved', subdivided or sold. There is strong evidence that Aboriginal people continued to live on this land until it was resumed for a migrant hostel in 1949 and it was generally believed that it had been reserved for the use of Aboriginal people, although a formal gazettal had never occurred. [4] Many people in the area believed right up till 1950 that this was Aboriginal reserve land.

Travelling on country – Biddy Giles, around Gurugurang

Another strategy to keep in touch with country was travelling to visit important places that held stories and productive resources. This can be seen in the story of Biddy Giles. She was a Dharawal woman who belonged to the country along the southern side of the Georges River and who travelled over her lifetime between Wollongong and Sydney areas. During her long life, she spent time around the southern Dharawal country of Wollongong, with her husband, Dharawal man Paddy Burragalang, as well as all along the Georges River and particularly in Gweagal country towards Kurnell. She spent time at the Kogarah Bay Aboriginal community on the northern side of the Georges River. As an old woman, she lived with her brother Joey near Sylvania on the big property then owned by Thomas Holt.

In the 1860s she lived at Guragurang (Mill Creek) with her second husband, Englishman Billy Giles. She often acted as a guide for settlers who wanted to hunt, fish and sightsee on the southern side of the river. Some of these travellers' accounts in newspapers show that Biddy was an accomplished fisherwoman and was very knowledgeable about the country. [5] She explained to them that she had learnt many of the stories as a child and she was a tireless teacher about the plants, animals and stories of her country.

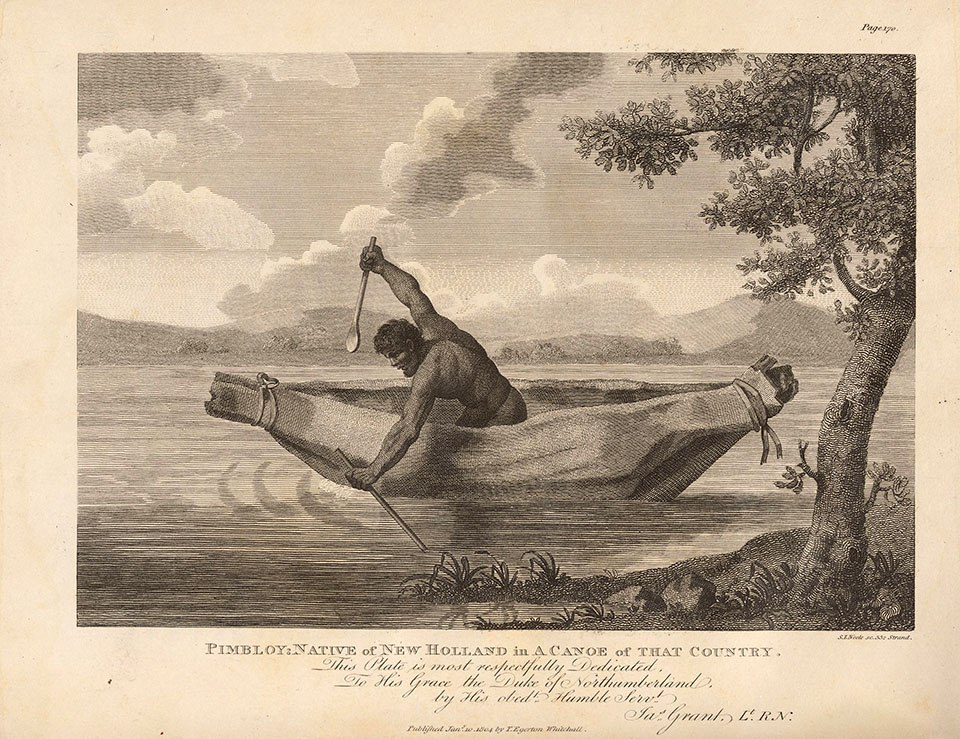

She used the river to move between places and to link up the many small settlements where Aboriginal people had continued to live on undeveloped 'commons' sandstone areas all along the river, which were unsuitable for intensive farming and so left alone by their white 'owners'. They were places between which Aboriginal people were able to move, to camp, and visit friends and country. Some were married to white people, others were living in small family groups or in working communities on the larger properties between the Georges River and Port Hacking. Some belonged to that country – others had come from distant places like Brungle to live on the Georges River for a while. [media]People like Jimmy Lowndes had been born on the Georges River and travelled to the Castlereagh River to work as a skilled horseman before returning to work on the Holt property at Sylvania. [6] The river provided a rich resource for them all, and enabled some Aboriginal people in the early nineteenth century to stay in touch with their country, despite the fact that white people hardly noticed them at all.

Buying land – Lucy Leane at Holsworthy

Lucy Leane was one person who held onto her country through purchase. She had been born Lucy Burn in 1840 at Holsworthy, where she had grown up, and later married an Englishman, William Leane. Together, they purchased two blocks on the eastern side of Williams Creek, just upstream of Jonathon Goggey's family home, and reared their 13 children. On the blocks they developed a flourishing farm of 82 acres (33.2 hectares), with cows and horses and a 10-acre (4-hectare) orchard, and began a successful vineyard employing Italian immigrant workers. They sent their younger children to school and their older children sought independent work and married (two of them married Italian farmers). [7] Lucy was proud of her Aboriginal ancestry and family, and developed strong relationships with people from all groups across the area, from her neighbours to the mayor. In 1893 she decided to write to the Protection Board, to seek the allocation of a boat in order to trade her farm produce along the river.

Lucy had no need to advertise her Aboriginality or to assert her connections to country or to the wider Aboriginal community. Yet she chose to stand proudly on just these grounds. Her petition to the Colonial Secretary, read:

Sir,

The petition of your humble Petitioner Lucy Leane showeth that She is the only surviving Native Woman of the Georges River and Liverpool District, residing here ever since her birth, Fifty Three years ago, as the undersigned witnesses can attest.

Being a bona fide Original Native of Australia and of this District, your Petitioner requests of you the supply of a boat as granted by the Government in all such cases, for the purpose of carrying on trade on the Georges River, and your Petitioner will ever pray.

Holdsworthy, Liverpool, 31 May 1893 [8]

The Protection Board responded that they intended their allocations to be made on the basis of need, not of the right of Aboriginal people to claim such recognition. Lucy was probably aware of the paternalistic intention of the Board, so it is all the more interesting that she chose such an assertive tone and recruited the support of such an array of local authorities. The Leanes' farm continued to be profitably farmed for an extended family – and provided funds to assist in the establishment of a number of satellite farms owned by their children, including their daughter Mary and her husband Salvatore Passanisi. [9]

There were other Aboriginal people who purchased land, but because few records were created there is far less known about their lives. Family histories are one of the ways in which their stories live on. Land purchases did continue, often unobtrusively, allowing those families to have spaces of security at least for a while.

One of Mary and Salvatore's daughters was Giuseppa Lucy Passanisi – named after her grandmother Lucy Leane. She married Joseph Henry Pike in 1912, the same year as the Army took away the Passanisi and Leane farms. Like many locally born young men, Joe Pike traced his background to convicts, but he had grown up with the Aboriginal and Italian families in the area. Guiseppa Lucy and Joe, along with other young families who were related by marriage to the Leanes, moved to the block of land at Voyager Point that Jonathon Goggey had saved in 1857. With other Aboriginal families, they set up homes on Portion 53, building five huts and farming a seven-acre (2.8-hectare) plot with around 50 fruit trees. They were living there in 1941 when the Trainer family moved onto the next block, called Pigface Point. Ted Trainer remembers visiting Portion 53 as a boy and meeting an Aboriginal woman who was probably Guiseppa Lucy Pike.

In 1949, despite having lived there for many years, the Pikes were suddenly faced with yet another dispossession. The Commonwealth government began resuming land to set up hostels for workers – including migrants – who were being brought to work in the new factories being set up along the river after the war. All of the spaces on which Aboriginal people had been able to find a place for themselves were now being taken over by the Army. This had happened at Herne Bay in 1942 and then at Voyager Point in 1949.

Joe and Guiseppa Lucy were forced to take shelter with other members of the Leane family who had already moved to Willoughby. But they didn't stop trying to get their place back on the Georges River. Joe Pike wrote again and again to the Commonwealth government between 1950 and 1954, drawing maps to show them what he called 'my land', and arguing the case carefully but passionately:

The loss of my land has been a great inconvenience to me, I must have some where to live.

The Commonwealth Government decided it would allow the Pikes to move back onto their land – but that they could not have an access or 'right-of-way' to it. This made it impossible for them to return. But they stayed with their families around Chatswood until at least the 1960s, maintaining the community networks despite the government having uprooted them from their land. Ever since, other members of the Leane family have been living in the wider area around Liverpool and Holsworthy. Lucy – and Jonathon Goggey before her – had laid the strongest of ground for the continuing story of Aboriginal people on the Georges River.

Place of refuge – Salt Pan Creek

Salt Pan Creek is the country of Pemulwuy [media]and the Bediagal clan of the Dharug people, on the northern shore of the Georges River, between what is now Padstow and Riverwood. Many Aboriginal people had camped there since the British settlement. But it was never a reserve or a mission.

Ellen Anderson[media] was Biddy Giles's daughter. Ellen had married Hugh Anderson from Cumeragunja and they lived at Salt Pan Creek for a decade before they bought a block of land in Ellen's name for the family in the 1920s. William Rowley, who had been born at Pelican Point near Weeney Bay, bought the block next to them. These two freehold blocks formed the nucleus of what many people remember as 'the Salt Pan Creek camp'. There were always spaces along the river as the land was heavily timbered and there were no farms on the sandstone. This was why Ellen and Hughie Anderson and William Rowley and his family were able to buy this land. The Anderson family grew: their youngest daughter, Dolly, married Tom Williams (Snr), a Kamilaraay man and World War I veteran from the Castlereagh River who refused ever again to live under Protection Board control. Like the Anderson and Rowley land, the surrounding area that was low-lying was also not attractive to subdivision and this meant that Doctor's Bush and other areas survived as open camping grounds into the 1930s.

[media]They lived on this land by working in cash jobs but also by using their knowledge of the flowers and game along the river and on the sandstone. Ellen and her grandchildren gathered the many wildflowers that grew along Salt Pan Creek and sold them door-to-door in the area. Her son Joe Anderson and his brothers gathered the vivid red gum tips and Christmas bush to sell at the markets when they spruiked on Friday nights. All the Aboriginal people living there were able to gather oysters, prawns and river fish as well as hunting swamp wallabies and other game.

Ellen and Hughie [media]were always outspoken. Hughie wrote for the local paper at Cumeragunja when he was younger. At Salt Pan Creek, Ellen and Hugh were in touch with the Aborigines Inland Mission. Through it, they met the people who set up the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) in the 1920s, Fred Maynard and Elizabeth McKenzie Hatton. The AAPA set up a safe house in 1924 in nearby Homebush for Aboriginal girls who had escaped – or as the Protection Board said, 'absconded' – from their apprenticeships. By 1927, the AAPA were in contact with Ellen's kinsfolk, the Duren family from Batemans Bay, who were protesting against the racial segregation of the public school there.

In the 1930s, the Salt Pan Creek camp became even more important. Because it was freehold land and not a mission or under any government control, it became a refuge for Aboriginal people who escaped from Protection Board control or pressure in the 1930s. There was always political talk going on. Jacko Campbell from Kempsey and Ted Thomas from Wallaga Lake remembered the camp:

Jacko: All them old fellas used to live out there, the Pattens and all them others. You'd see them old fellas sittin around in a ring, when there was anything to be done.

Ted: They were well educated! They could talk on politics!

Jacko: They always DID! Around the kids! No matter where they went!

'Specially when there was anything to do about the Aborigines Protection Board! There was talk about writing a petition. That was always goin' on! Joe Anderson said he'd be talking to the Duke of Gloucester! [10]

Jacko remembered that Ellen's son, Joe Anderson, used to talk on a soapbox at Paddy's Markets on Friday night. Joe was protesting about the Protection Board taking land and children away. Jacko Campbell remembered:

Every Friday night they used to be spruiking at Paddy's Market. Jack Patten, Bill Onus, Bob McKenzie from Woolbrook, old Joe Anderson, they all lived at Salt Pan They'd only be spruikin' on land rights, that's all, on land rights You know: 'Why hasn't the Aboriginal people got land rights?' That was always the [thing]. [11]

People who came to live at Salt Pan learnt a lot from all those talks around the campfire. Many of them went on to become important political activists, including Jack Patten, Bert Groves, and Tom Williams (jnr) and Ellen James, both grandchildren of Ellen Anderson.

Ellen and Hughie Anderson's family came under pressure once the old people died. Local white neighbours tried to move away all of the Aboriginal people in the area because they wanted to expand the residential subdivision onto the sandstone escarpment.

Joe, as the eldest in the family, tried to fight off this pressure by talking to the newspapers and going to the meetings of Bill Ferguson, Jack Patten and Pearlie Gibbs's new Aborigines Progressive Association. He was filmed talking at Salt Pan Creek in 1931. Joe took the name of Burraga, from Ellen's father's name, Paddy Burragalang.

Joe said:

Before the white man set foot in Australia, my ancestors had kings in their own right, and I, Aboriginal King Burraga, am a direct descendant of the royal line…

The Black man sticks to his brothers and always keeps their rules, which were laid down before the white man set foot upon these shores. One of the greatest laws among the Aboriginals was to love one another, and he always kept to this law. Where will you find a white man or a white woman today that will say I love my neighbour It quite amuses me to hear people say they don't like the Black man ... but he's damn glad to live in a Black man's country all the same!

I am calling a corroborree of all the Natives in New South Wales to send a petition to the King, in an endeavour to improve our conditions. All the Black man wants is representation in Federal Parliament. There is also plenty fish in the river for us all, and land to grow all we want.

One hundred and fifty years ago, the Aboriginal owned Australia, and today, he demands more than the white man's charity. He wants the right to live! [12]

Hostels and housing commission – Herne Bay and Green Valley

There was a large area of 'vacant' land on Salt Pan Creek. This low-lying area called Doctor's Bush was upstream of the Anderson and Rowley blocks. Aboriginal people had been living there in camps and huts, through the Depression and right up till late in the 1930s. During World War II, an American army hospital was built on Doctor's Bush and the Aboriginal people there were forced to move away. This happened in other places where the low-lying land had been left open and accessible for Aboriginal people – like Goggey's land at Holsworthy.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Aboriginal people came to the city from all over New South Wales and interstate. The government was pushing for more factories and the factories needed more workers. Some people came to the city for work, some for better education and some for better medical services. Some came to get away from the racism in country towns.

Most went to Redfern, Glebe, Waterloo and other places in the inner city first. The severe housing shortage meant it was hard to find places to buy or to rent. Aboriginal people often had to stay with relations in overcrowded houses and flats. The government had just set up the Housing Commission and going to one of their hostels was an important way to get better housing.

Housing Commission hostels were temporary housing for inner city families and migrant workers. Most of the hostels were built along the Georges River because that was also where many of the new factories were being built. Some were in old Army buildings like the US Army hospital at Herne Bay while others were built quickly like the Migrant Workers' Hostel at East Hills to house the many people who needed shelter.

Aboriginal people came from the inner city to the hostels at Herne Bay on Salt Pan Creek and Hargrave Park at Warwick Farm in the 1950s and 1960s. Both of them were close to the river. People who came as children to these hostels from country river towns remember they often went looking for the closest river to swim and fish – as it reminded them of home. There are lots of memories of Salt Pan Creek and the river around Hargrave Park.

The hostel housing was poor quality, noisy and crowded but at least everyone was close. It was hard to feel lonely there! The kids all played together and ate dinner at each others' houses. Many families from all over the state met each other there for the first time. But there was also hostility from the surrounding suburbs against the new arrivals. Herne Bay was nicknamed 'Hoon Bay' and the kids had to stick together and stand up for each other.

New suburbs and a new community

[media]The government began to subdivide large properties to build new Housing Commission permanent housing in a few big centres. Many Aboriginal people from Herne Bay and Hargrave Park went to the new suburb at Green Valley, a dairy farm subdivided just northwest of Liverpool, in 1963. The government had scooped up all the topsoil to sell before it built the huts, so the earth around the new fibro houses was just bare clay. Others went to Mt Druitt, near Blacktown. Later, Aboriginal families moved back into other suburbs all along the Georges River, like St John's Park and Beverly Hills.

There are many families who could tell stories about Green Valley. Ruby Langford-Ginibi lived there and wrote about her life in this new, bare suburb in her book Don't Take Your Love To Town. [13]

Government policy in the 1960s was to separate Aboriginal families from each other, putting them at least two or three streets away from each other. The policy aimed to break apart the social bonds which held Aboriginal communities together. Many Aboriginal people felt lonely and isolated. Some people remember good friendships with neighbours who were not Aboriginal. Other Aboriginal people were met with racism when they moved into their new Housing Commission houses, even though everyone in the street was renting and they were all on low incomes. These Aboriginal people remember they had to struggle to be recognized and respected.

The new Housing Commission suburbs was challenging too because there were few shops and only occasional buses. People at Green Valley had to come into Liverpool to shop and teenagers remember walking long distances just to go swimming at the Liverpool Weir or go to the pictures.

But the Weir and the river were good places to get to know people and before long Aboriginal people all over the new suburbs were beginning to meet up with each other. Some people were very important in helping Aboriginal families to meet up, despite the government attempts to keep people apart. Charles Leon was one of those people who is remembered with warm affection by many people. He always had time to sit and talk to people who had been isolated by racism and distance. He played a big role in helping communities to reform in this tough new environment.

Aboriginal people who had arrived in the 1960s began to learn more about the Aboriginal people who had lived here before they arrived. Aboriginal people we have talked to remember learning about the Appin Massacre, Pemulwuy, Kogi and the many challenges the people of the river made to the new settlement in the early days. Bert Groves came back to live at the suburb of Herne Bay and told people about the old Salt Pan Creek camp. Tom Williams Jnr became an important community leader with the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs who worked all along the river from his home at La Perouse. Families grew up and young people married and had their own children in the area, making them feel closer to the river country.

In the 1970s the Georges River Aboriginal community was actively involved in the political campaigns like the Black Moratorium and the Embassy in 1972. Pat Eatock was one Green Valley resident who had a major role in the campaigns. In the mid 1970s, elders like Jacko Campbell and Ted Thomas explained to people the importance of the free community at Salt Pan Creek which had challenged the government.

Women have been important all along the river in building community strength and they were important too in the grass roots campaigns for land. The St John's Park Women's group in the 1970s is an important example. This was a local, low-key group of women who first got together to organize child care and a women's education group. Elders like Ellen James (Tom Williams' sister and Ellen Anderson's granddaughter) were involved alongside longtime Georges River residents like Robyn Williams and the many women who had come to the river in the 1950s and 60s like Judy and Janny Smith, later known as Judy Chester (now deceased) and Janny Elly. These women became concerned about the best way to look after the country in which their children had been born. The St John's Park women began to work, just as hard and still without any funding, to build the networks which became the Gandangara Local Aboriginal Land Council in 1982, claiming land around Menai and building up the wider educational and labour movements of the river.

Saving the river

The river was in a sorry state by the 1960s. The factories where many Aboriginal people and other Housing Commission residents were working were also pouring industrial pollution into the water. The hostels themselves, the Army base at Holsworthy and the new subdivisions were badly serviced. A piped sewage network did not begin to work till the late 1960s and sewage flowed into the river. At the same time, the sandy bed of the river was being dredged for sand for the rapid building of houses across the city.

The new technology was allowing chlorinated swimming pools – 'The Baths' – to open in towns like Bankstown and Liverpool. It was expected that people would turn away from the polluted rivers but Aboriginal people continued to use the river. They swam in Liverpool Weir and the netted baths at East Hills. They fished and gathered prawns in Salt Pan Creek. Swimming at the weir and in the river was cheaper than the flash new 'Baths'. It was not under the control of councils – and it was more fun!

Aboriginal people felt rising concern too. They noticed the changes in fishing and riverbank life. Particularly fishermen and women began to worry. These concerns have developed into the Aboriginal involvement in river protection today. Lewis Solberg has represented the Gandangara Land Council on the Sydney Metropolitan Catchment Management Authority Local Establishment Team. A group of young people 'The Towra Team' from La Perouse works with Department of Environment and Climate Change to conserve and protect Towra Marine Conservation area near Weeney Bay where William Rowley lived. Aboriginal people are helping to restore the river to become the healthy and productive place it had always been under Aboriginal management.

References

Heather Goodall and Allison Cadzow, Rivers and Resilience: Aboriginal people on Sydney's Georges River, UNSW Press, 2009

Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2009

Notes

[1] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2009

[2] Heather Goodall and Allison Cadzow, Rivers and Resilience: Aboriginal People on Sydney's Georges River, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2009

[3] Heather Goodall, 'Authority Under Challenge: Pikampul Land and Queen Victoria's Law During the British Invasion of Australia' in Martin Daunton and Rick Halpern (eds), Empire and Others: British Encounters with Indigenous Peoples 1600–1850, University College Press, London, 1999, pp 260–279

[4] Heather Goodall and Allison Cadzow, Rivers and Resilience: Aboriginal People on Sydney's Georges River, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2009, chapters 3 and 7

[5] St George Call, 19 January 1904; 23 January 1904; 30 January 1904; 17 August 1904; 11 May 1907

[6] St George Call, 14 May 1904; RH Mathews and MM Everitt, 'The Organisation, Language and Initiation Ceremonies of the Aborigines of the South-East Coast of NSW', Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, vol 34, 1900, pp 262–281

[7] W Saunders, Senior Constable Liverpool Police to Aboriginal Protection Board, 18 July 1893, Colonial Secretary's In Letters, 5/6135 [93/7210] State Records of New South Wales

[8] Signed by numerous witnesses including the Mayor of Liverpool, numerous aldermen and the local school teacher. Mrs Lucy Leane, petition to Colonial Secretary, 31 May 1893, Colonial Secretary Main Series, letters received, 1826–1982, NRS 905, container 5/6135 [93/7210] State Records of New South Wales

[9] Heather Goodall and Allison Cadzow, Rivers and Resilience: Aboriginal People on Sydney's Georges River, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2009, chapter 3

[10] Jacko Campbell and Ted Thomas, Interviewed by Heather Goodall, 24 September 1980

[11] Jacko Campbell and Ted Thomas, Interviewed by Heather Goodall, 24 September 1980

[12] 'Australian royalty pleads for his people', Cinesound Review, 100, 29 September 1933

[13] Ruby Langford-Ginibi, Don't Take Your Love To Town, Penguin, Sydney, 1988

.