The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Bidura

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Bidura

Bidura, [media]at 357 Glebe Point Road, Glebe, is a heritage-listed Victorian Italianate villa and Glebe landmark that played a vital role in the New South Wales Government's child welfare system from 1920 to 1977. It was depot and receiving home – a holding institution – for girls and very young boys while they waited to be taken to the Children's Court or were moved between foster care and government institutions. As the primary hub for child welfare in Sydney, Bidura is a place shared by members of the Stolen Generations and Forgotten Australians and is remembered by them with little fondness.

The history of the house

Bidura[media] stands on Cadigal and Wangal land which was granted to the Church of England in 1789 as the Sydney Glebe and subdivided in stages after 1828. [1] The allotment where Bidura now stands was acquired in 1857 by Edmund Blacket, who had based himself in Glebe since resigning his position as colonial architect to work on the University of Sydney in 1854. [2] Blacket designed and completed his residence Bidura in around 1862, and five of the eight Blacket children were born there before Blacket's wife, Sarah, died in 1869. [3] The following year the house was sold to Mrs RM Stubbs wife of the auctioneer RF Stubbs. [4]

Sands Directory shows that the Stubbs family called the house 'Madwia' and 'Bedura'. Around 1879 they sold it to Frederick Perks who used the original name for the house and is thought to have added the ballroom some time before 1910. [5]

The New South Wales Government bought Bidura in 1920 to serve as a new depot for what was then called the State Children's Relief Board. Its large rooms meant it could easily be converted to dormitory-style accommodation for children and its spacious gardens were considered positive surroundings for neglected children. [6]

Bidura's role in the child welfare system

In the early twentieth century the vast majority of dependent children in state care in New South Wales were placed in the boarding out system (foster care), although the government ran institutions such as the cottage homes and farm school at Mittagong and the training schools (reformatories) at Parramatta and Mount Penang. The Aborigines Protection Board and Welfare Board ran a separate system and placed children in apprenticeships or in its homes at Cootamundra and Kinchela. [7]

[media]Under the laws of the time, children at risk were 'charged' with neglect and brought before children's courts which dealt with neglect abuse and children's minor offending. Children's court judges could place a child on probation with its parents, in the hope of improving the home situation, or make children wards of the state and place them into foster care or institutions. The most important court was the Metropolitan Children's Court and Depot which began in the grand Paddington mansion Ormond House (Juniper Hall) in 1905 and then, in 1912, moved into a purpose-built courthouse in Albion Street Surry Hills. [8]

In 1920 the State Children's Relief Board bought Bidura to replace the depot and receiving home at Ormond House and service the Metropolitan Children's Court. Two years later it bought Royleston, also on Glebe Point Road, as a boys' depot. [9] When the State Children's Relief Board was reformed to become the Child Welfare Department in 1923, Bidura was designated the Metropolitan Girls' Shelter. [10]

Bidura was for girls up to the age of 18 and for boys up to the age of six years. By the 1930s the Child Welfare Department attached a school to the building and employed a governess because the residents of Glebe had opposed the attendance of state children at local schools. As one former resident put it 'this was one room in the grounds with no qualified teacher. We did craft mainly puppets.' [11]

[media]By the 1930s the Metropolitan Girls' Shelter operated at the rear of the property in a terrace entered from Avon Street. [12] From the 1940s, children who were removed from their families by courts in the Australian Capital Territory were transferred to New South Wales via Bidura. [13]

Bidura was the first place most children saw after they were taken from their families. It was the central point of child welfare in New South Wales, and the site of the department's clothing depot, so was constantly busy with children and departmental officers. While both Bidura and Royleston were intended as temporary accommodation, in reality children stayed for long periods, particularly if they were assessed as 'hard to place'. They also returned between placements or for 'holidays'. As a result, the house looms large in the memories of many people who grew up in out-of-home care.

Bidura and the Stolen Generations

New South Wales ran separate and distinct welfare systems for black and white children as the prevailing belief was that Aboriginal children needed special training to fit into white society and were therefore unsuitable for fostering. The Aborigines Protection Board made decisions about the children who lived on its reserves and stations but the State Children's Relief Board removed children from families who were living independently of Board surveillance. [14]

In 1915 the State Children's Relief Board president, AW Green, complained that the Board was expelling families from reserves which compelled the State Children's Relief Board to act and resulted in 70 to 80 'black and quasi-black' children being sent to ordinary institutions. [15] After this outburst the Aborigines Protection Board and the State Children's Relief Department began to work together to process removals in children's court hearings. Children with darker skins, or who had grown up on a reserve, were usually apprenticed or sent to the Aborigines Protection Board homes at Cootamundra and Kinchela, although a number of girls were sent to Parramatta Girls Training Home. Lighter-skinned children were classed as white and placed in mainstream institutions. [16] Most of the girls and young boys processed at the Metropolitan Children's Court, and many from regional areas, passed through Bidura over the next 30 years.

In 1943 the Aborigines Welfare Board replaced the Aborigines Protection Board and focused on assimilating Aboriginal people into the white mainstream. Aboriginal children were dealt with by the Child Welfare Department under the Child Welfare Act 1939 and for the first time efforts were made to place them in foster homes usually with white families. [17] Bidura remained a transit point, not least because the assimilation era coincided with laws enabling the transfer of children from the Australian Capital Territory to New South Wales, some of whom were Aboriginal. Staff of the Northern Territory Library have also identified that a number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from the Northern Territory were sent to Bidura before being taken to Winbin, a government children's home in Strathfield. [18]

Life in Bidura

It is clear from oral history accounts that arriving at Bidura was confusing, frightening and humiliating, particularly when it involved being wrenched away from male siblings. Families separated at Bidura spent years apart, and sometimes never reunited, while members of the Stolen Generations suffered additional losses through denial of their Aboriginality. [19]

Carmel Durant, who was taken to Bidura in the 1930s when her parents were unable to care for her, described the drill on arriving:

On arrival our small suitcase was taken, [and we] were issued with blue uniforms and black stockings. We were chastised for not saying 'thank you' to the person in charge when we received our outfits. Most embarrassing, was having to strip in front of at least six complete strangers…walk up three steps to the bath and, as a matter of routine, having your head 'treated', no matter what your age. Within a week or so we were taken to Camperdown Hospital to have our Tonsils and Adenoids removed. [20]

The 'treatment' (for head lice) was having hair doused in kerosene and bound in rags. [21]

Many girls were subjected to internal examinations at Bidura on the assumption that they had been abused or were sexually active. A former resident, who was returned to Bidura in the 1960s after falling out with her foster parents, described this terrifying procedure:

On arrival back at Bidura I was given the standard vaginal tests – legs tied in stirrups. When I protested I was told they knew 'how quickly I would open my legs for a boy!'

I was 9 years old! I had no idea what they were talking about. The pain was horrific I was crying the matron just pulled me off the table told me to 'shut-up as I was nothing but a dirty stealing tramp'. [22]

This procedure was invariably repeated at every institution the girl passed through.

Older girls tended to be placed in the Glebe Girls' Shelter, which some girls knew as Glebe Detention Centre. One former resident said it was a beautiful 'old brick terrace building with great character.' [23] Christine Riley, a Wiradjuri woman who was in Ormond School and Parramatta Girls' Home and had regular stints of six to eight weeks in the Glebe Shelter, has very different memories:

The Female office[r]s were as cold hard and cruel as the building itself with their hard faces and demanding instructions of perfection in attitude and conduct and work detail…the code of silence forced upon the girls created depression…I was one of those girls living with fear of not knowing what was ahead of me; suicide was always on my mind…That's how depressing this place The Glebe Shelter was, there was hardly any sunlight at all and only one small section in the court yard outside were all you could see was the cold sandstone walls standing tall, and only seeing a small spot of the sky above, and inside nothing but the solid doors with heavy padlocks and cold cement floors. [24]

Changing attitudes and closure

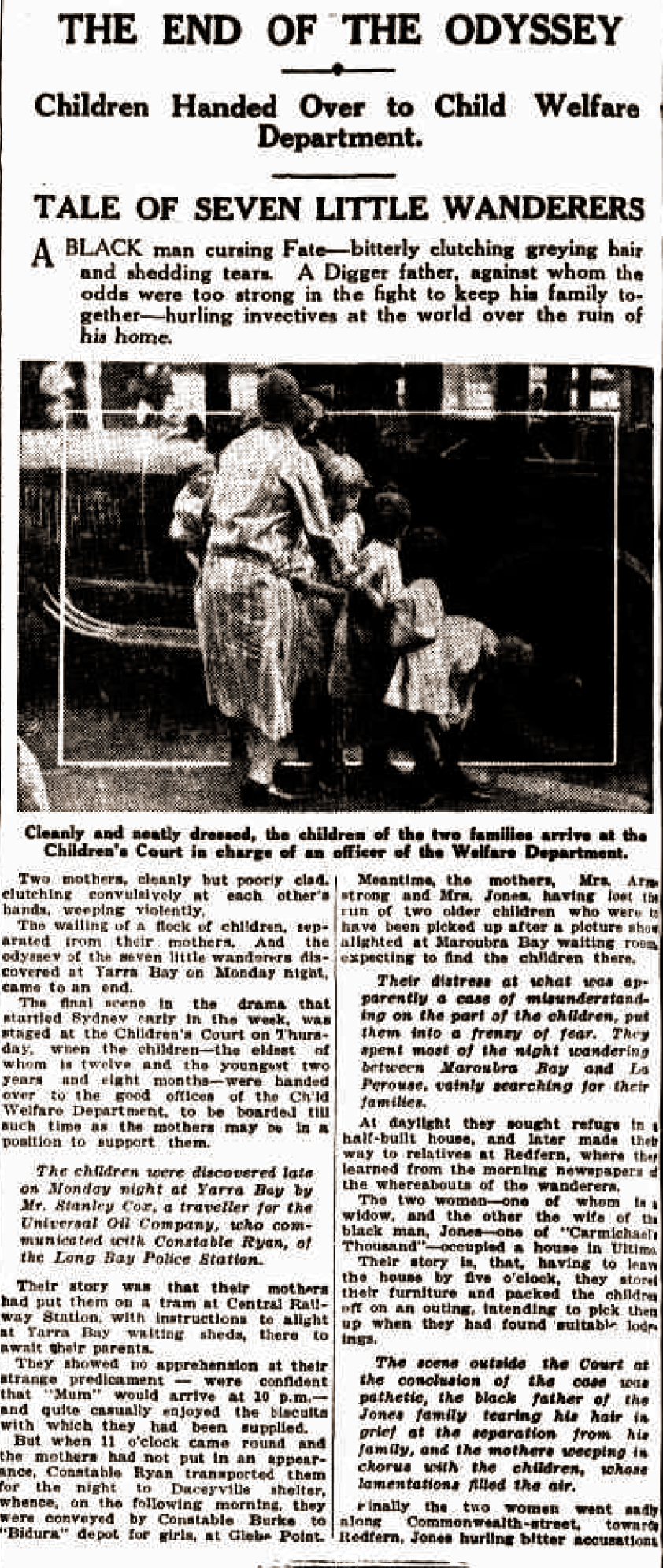

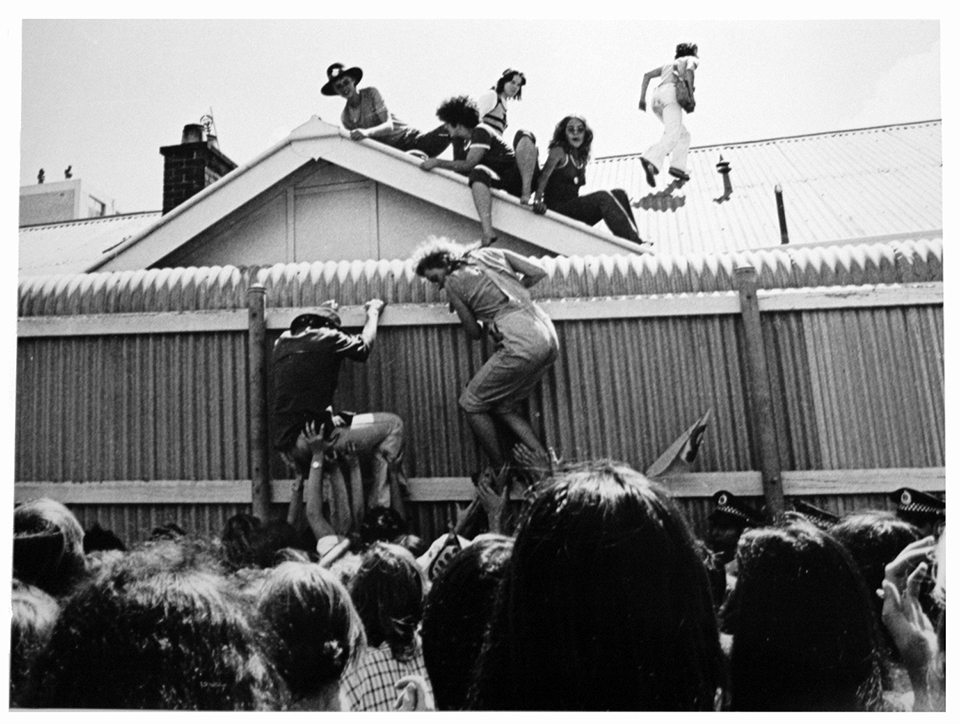

[media]In the 1970s Bidura and the Shelter, along with Parramatta Girls' Home and Hay Institution for Girls, were targeted by Bessie Guthrie and activists from the Women's Liberation movement for abuses against young women. [25] Community attitudes were also shifting and institutions like Bidura began to seem archaic and brutal.

[media]In 1977 Bidura was closed as a residential facility. The Shelter was demolished in 1978. [26] However, the property continued to be part of the child welfare and juvenile justice system. Bidura Children's Court, a neo-brutalist building erected on the site of the Shelter, opened in 1983, replacing the Albion Street Metropolitan Children's Court. Bidura was then restored by the New South Wales Department of Public Works and was used as office space for what is now the New South Wales Department of Family and Community Services. [27] [media]In December 2014 the New South Wales Government announced that it had sold the Bidura Children's Court complex, including the historic house, for residential development. [28]

Further Reading

Find & Connect Web Resource Project for the Commonwealth of Australia The Find & Connect web resource 2011 www.findandconnect.gov.au

Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants Oral History Project and National Library of Australia You Can't Forget Things Like That: Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants Oral History Project. Canberra: National Library of Australia 2012

Mellor Doreen and Anna Haebich eds. Many Voices: Reflection on Indigenous Child Separation Canberra: National Library of Australia 2002

Parry Naomi. '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in NSW and Tasmania 1880–1940.' PhD Thesis University of New South Wales 2007 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/4033481

Notes

[1] Heritage Branch House 'Bidura' including interiors former ballroom and front garden State Heritage Inventory NSW Environment and Heritage http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2427867 viewed 3 November 2014

[2] Heritage Branch House 'Bidura' including interiors former ballroom and front garden State Heritage Inventory NSW Environment and Heritage http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2427867 viewed 3 November 2014

[3] HG Woffenden 'Blacket Edmund Thomas (1817–1883)' Australian Dictionary of Biography (Canberra: National Centre of Biography Australian National University 1969) http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/blacket-edmund-thomas-3005/text4395 viewed 25 November 2014

[4] Heritage Branch House 'Bidura' including interiors former ballroom and front garden State Heritage Inventory NSW Environment and Heritage http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2427867 viewed 3 November 2014

[5] Sands Directory cited Heritage Branch House 'Bidura' including interiors former ballroom and front garden State Heritage Inventory NSW Environment and Heritage http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2427867 viewed 3 November 2014

[6] New South Wales Child Welfare Department Report of the Minister of Public Instruction on the Work of the Child Welfare Department (Sydney: Department of Education 1923)

[7] Naomi Parry '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in NSW and Tasmania 1880–1940.' PhD Thesis UNSW 2007 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/4033481 viewed 25 November 2014

[8] Christa Ludlow 'For Their Own Good': A History of Albion Street Children's Court and Boys' Shelter (Sydney: Network of Community Activities 1994); Naomi Parry '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in NSW and Tasmania 1880–1940.' PhD Thesis UNSW 2007 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/4033481 viewed 25 November 2014; Crawford John 'Establishment of the Children's Court' in History of the Children's Court Lawlink Lawlink NSW 2012 http://www.childrenscourt.justice.nsw.gov.au/childrenscourt/history.html viewed 25 November 2014

[9] State Children's Relief Board Report of the State Children's Relief Board (Sydney: Government Printer 1920–1923)

[10] New South Wales Child Welfare Department Report of the Minister of Public Instruction on the Work of the Child Welfare Department (Sydney: Department of Education 1923)

[11] Carmel Durant 'Our Story' Inside: Life in Children's Homes viewed 25 November 2014 http://nma.gov.au/blogs/inside/2010/03/05/our-story/

[12] New South Wales Child Welfare Department Report of the Minister of Public Instruction on the Work of the Child Welfare Department (Sydney: Department of Education 1939)

[13] Naomi Parry Transfer of children from Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Norfolk Island to New South Wales (NSW) (1941–1986) Find & Connect web resource http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/act/biogs/AE00131b.htm viewed 25 November 2014; Naomi Parry Winbin (1954–1975) Find & Connect web resource http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/nsw/NE01056 viewed 25 November 2014

[14] Naomi Parry '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in NSW and Tasmania 1880–1940.' PhD Thesis UNSW 2007 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/4033481 viewed 25 November 2014; Peter Read The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal Children in NSW 1883–1969 (Sydney: (New South Wales) Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs Occasional Paper (No. 1) and Aboriginal Children's Research Project (NSW Family and Children's Services Agency) 1981)

[15] SCRD Annual Report 1915 cited in Naomi Parry '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in NSW and Tasmania 1880–1940.' PhD Thesis UNSW 2007 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/4033481 viewed 25 November 2014 293

[16] Naomi Parry '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in NSW and Tasmania 1880–1940.' PhD Thesis UNSW 2007 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/4033481 viewed 25 November 2014; Peter Read The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal Children in NSW 1883–1969 (Sydney: (New South Wales) Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs Occasional Paper (No. 1) and Aboriginal Children's Research Project (NSW Family and Children's Services Agency) 1981)

[17] Naomi Parry '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in NSW and Tasmania 1880–1940.' PhD Thesis UNSW 2007 http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/4033481 viewed 25 November 2014; Peter Read The Stolen Generations: The Removal of Aboriginal Children in NSW 1883–1969 (Sydney: New South Wales Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs Occasional Paper (No. 1) and Aboriginal Children's Research Project (NSW Family and Children's Services Agency) 1981)

[18] Naomi Parry Winbin (1954–1975) Find & Connect web resource http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/nsw/NE01056 viewed 25 November 2014

[19] Christine Ohrin interviewed by Tikka Wilson Bringing them Home Oral History Project National Library of Australia http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn731489 1999 viewed 25 November 2014; Cleonie Quayle interviewed by Jenny Gall in the Bringing them home oral history project National Library of Australia http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn1608171 viewed 25 November 2014

[20] Carmel Durant 'Our Story' Inside: Life in Children's Homes http://nma.gov.au/blogs/inside/2010/03/05/our-story/ viewed 25 November 2014

[21] 'Submission 272' in Senate Community Affairs Committee Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care –Submissions received by the committee as at March 17 2005 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia 2005) http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/inst_care/submissions/sublist viewed 14 November 2014

[22] 'Submission 258' in Senate Community Affairs Committee Inquiry into Children in Institutional Care–Submissions received by the committee as at March 17 2005 (Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia 2005) http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Completed_inquiries/2004-07/inst_care/submissions/sublist viewed 14 November 2014

[23] Naomi Parry Metropolitan Girls' Shelter Glebe (c. 1923–1978) Find and Connect web resource http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01392b.htm viewed 25 November 2014

[24] Christine Riley 'The Glebe Shelter for Girls' The Life of Riley http://lifeofriley.net.au/institions/glebe-shelter.html viewed 3 November 2014

[25] Judy Rapley 'Creating a Space: The Life of Bessie Guthrie' ABC Radio National Hindsight 28 October 2007 http://www.abc.net.au/rn/hindsight/stories/2007/2064266.htm; Suzanne Bellamy 'Guthrie Bessie Jean Thompson (1905–1977)' Australian Dictionary of Biography National Centre of Biography Australian National University http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/guthrie-bessie-jean-thompson-10382/text18393 viewed 13 December 2014

[26] Naomi Parry Metropolitan Girls' Shelter Glebe (c. 1923–1978) Find and Connect web resource http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01392b.htm viewed 25 November 2014

[27] Heritage Branch House 'Bidura' including interiors former ballroom and front garden State Heritage Inventory NSW Environment and Heritage http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=242786 viewed 3 November 2014

[28] Leesha McKenny 'Australian Technology Park sale: call for expressions of interest' The Sydney Morning Herald http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/australian-technology-park-sale-call-for-expressions-of-interest-20141208-12050u.html viewed 13 December 2014; NSW Office of Finance and Services Ministerial Media Release 'Government land in Glebe could house new units' http://www.finance.nsw.gov.au/government-land-glebe-could-house-new-units viewed 13 December 2014