The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Keith Kinnaird Mackellar

Keith Kinnaird Mackellar 1898-1899, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW ( State Library of New South Wales (PXE 1193, 1)

Keith Kinnaird Mackellar 1898-1899, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW ( State Library of New South Wales (PXE 1193, 1)

Listen to Nicole and Tess on 2SER here

Keith Kinnaird Mackellar was born in 1880 in the harbourside suburb of Point Piper where the Mackellar children had an idyllic and privileged childhood. He was educated at Sydney Grammar School and became a junior officer in the NSW Scottish Rifles at the age of 18. A talented athlete, he was also enrolled as an undergraduate in first year Arts at the University of Sydney in 1899. When the Boer War broke out in South Africa in 1899, Mackellar joined the Mounted Infantry Unit and left Sydney in January 1900. He wrote detailed letters to Dorothea and his family about life in the war, even writing for Sydney Grammar School’s journal The Sydneian. In one article he wrote: ‘Every day there is something – either we occupy a farm and eat its ducks, or we get fired at from under a white flag, or from out an ambulance waggon, by gunners wearing the red cross. The more we see of South Africa the more we appreciate Australia….’ On 11 July 1900, Mackellar was shot in the head during a skirmish and killed. It is said the Boers lured Mackellar and his men to their farm by dressing in the uniforms of the Australian Light Horse. He was buried at a farm nearby, and then in a cemetery in Pretoria. Mackellar’s family didn’t hear of his fate for several days. His death deeply affected his younger sister Dorothea for the rest of her life, and it is believed to have inspired her first published poem, ‘When It Comes’, which she wrote at about the age of 15. Harper's Monthly Magazine, July 1903, Vol 107, p260, courtesy Internet Archive

Harper's Monthly Magazine, July 1903, Vol 107, p260, courtesy Internet Archive

In 1907, the Keith Kinnaird Mackellar ceramic memorial tablet was placed above the inner ward doors of the Victoria and Albert Memorial Pavilions at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, where his father, Dr Charles Mackellar, was the director. The dedicated tablet is now attached to the wall in the Emergency Department of Royal Prince Alfred Hospital.

His family also commissioned a beautiful stained glass window depicting Mackellar as St George the patron saint of soldiers and memorial plaque that you can see on the northern wall of St James church in the city.

Categories

Robert Wainwright, Rocky Road

Robert Wainwright, Rocky Road

Allen and Unwin, 424pp., ISBN: 9781760291556, p/bk, RRP: $32.99

‘Life is like a box of chocolates – you never know what you’re gonna get’ – Forrest Gump’s philosophising may not be the most prosaic observation but it is certainly true of the family behind the Darrell Lea chocolate shops. In his twelfth book, former journalist Robert Wainwright tells the story of Monty Lea and his irrepressible but forbidden love and marriage to Valerie Everitt, who was a vivacious, curvaceous sixteen year old when they met. This is not new ground, Brenda Lea’s How Sweet it is: The Darrell Lea story was published in 2012. However, Wainwright uses his investigative research skills to uncover the untold story of the Jewish family behind the iconic candy business. Rocky Road is a sobering and tragic family saga – Valerie wanted many children but birthing complications meant she had to stop after four. She went on to adopt three more children and it is their stories that are the focus of Wainwright’s book. He doesn’t trust the smiling family happy snaps and home movies – today's equivalent of Instagram and Facebook posts. By speaking to the family members, and with access to Valerie’s diaries and letters, he uncovers the bitter story of family divisions which lead to the demise of their sweets business. The Darrell Lea story starts on Manly’s Corso in 1916 when Monty’s father Harry – born Manessah Jablinovich in East London, but who later changed his name to Harry Levy and then Lea – wanted something to sell in the winter when people weren’t buying his fruit and vegetables. Chocolates and candies, supposedly made to old European recipes, were the answer and he could sell them by the wheelbarrow full on the Manly ferry. This proved so successful that Harry expanded to a tiny shopfront in Haymarket. By 1928 the family-owned and operated business had grown so much that they could afford to move to the retail precinct of Pitt Street. Six years later, Harry and his quartet of sons (Monty was the second child) were operating a dozen stores in and around the CBD. Darrell was the name of Harry’s fourth son, born when business was booming. Wainwright’s descriptions are visual and evocative: ‘Whatever they were selling, the displays were a kaleidoscope of colour. . . There was affordable joy in a Darrel Lea window . . . As if rebelling against the sad drabness of the Depression’ (p.22). Sydney-siders might recall the Darrell Lea shop in Pitt Street with its pyramids of enticing sweets and chocolates. From 1935 the sales girls wore pink uniforms with a big bow at the collar, which made them look like a wrapped box of chocolates. These were a ‘one size fits all’ creation – even pregnant women could wear them. They were designed by Valerie, who had studied dress-making before becoming a ticket writer for Darrell Lea. Wainwright reveals that Darrell Lea prices were written on ‘tickets’ which had a yellow background and red lettering – colours that hamburger empire McDonalds later adopted. Research shows that red increases your appetite and yellow is seen as a warm and friendly colour. Wainwright tells this classic migrant success story succinctly in the first three chapters, leaving him 370 pages to detail and analyse its unravelling. By 2012, the bitterness and rivalry between Monty and Valerie’s seven children contributed to the family company collapsing into voluntary administration. This rags-to-riches-to-rags tale is sure to fascinate those who have a soft spot (centre?) for the Sydney start-up, Darrell Lea. Reviewed by Alison Wishart, September 2018. Visit the publisher's website here: https://www.allenandunwin.com/browse/books/other-books/Rocky-Road-Robert-Wainwright-9781760291556Categories

Helen Pitt, The House

Helen Pitt, The House

Helen Pitt, The House

Allen & Unwin, 432pp., ISBN 9781760295462, p/bk, AUS$32.99

Helen Pitt launches head first in to over six decades of turmoil and tribulation on Bennelong Point in The House, available now from Allen & Unwin. She sets a cracking pace with vignettes that dart between Sydney and exotic overseas locales of America, Europe and Scandinavia in an effort to cover the major milestones in the life of the Sydney Opera House. Since the 40th birthday of the Sydney Opera House in 2013 there has been renewed interest in this iconic piece of the built environment. Jørn Utzon, Peter Hall and Ove Arup have all received special attention and the building itself has continued to attract widespread interest. It could have been easy to fall into the trap of retelling the well-known stories of this building’s history, yet Helen Pitt has instead drawn out the intensely human side of the Sydney Opera House detailing the impact it has had on both the citizenry of Australia and the workforce that slogged away for over 13 years of construction works as the drama of the building unfolded. As a history, the narrative is defined by time, something that was not on NSW Premier J.J. Cahill’s side when he announced that, not to be out done by southern rival Melbourne and its Olympic Games, and after years of passionate petitioning by Eugene Goossens (who was then holding the roles of Chief Conductor of what is now the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and Director of the Conservatorium of Music), that Sydney would finally have its own opera house. Cahill showed remarkable conviction, for a man more interested in cricket than Carmen or Chopin, for an unfunded idea. A design competition was held , entry 218 was selected as winner and the NSW Government committed to build the entry by the, then relatively unknown, Dane, Jørn Utzon. Pitt uses her journalistic background to weave a faithful retelling of the major events as the design went from a “magnificent doodle” to a modern wonder of the world. From the commencement of works on site through to the “spherical solution” which resolved the engineering puzzle of building the now-famous shells, Pitt explores the highs and lows of life on the construction site and lays these out for the reader to experience. The pages of The House cover high society events and antics of soirées and staff on Australia’s most controversial construction site. The often still raw and unresolved tensions between supporters of Hall who was called upon to complete the building in 1966 and Utzon who was unceremoniously dismissed after almost a decade on the project are acknowledged and delicately addressed, though Pitt’s sympathies do fall slightly on the side of Hall. This work also looks at the more recent history of the Opera House with the same pace and investigative quality dedicated to the building’s beginnings. Just as Goossens had promoted and agitated for the Sydney Opera House half a century earlier, Elias Duek-Cohen who spearheaded the “bring back Utzon campaign” had been actively promoting and encouraging the Government to re-establish a relationship with Utzon, a goal that was achieved in the early 2000s. If there were to be a criticism of the book it is the lack of referencing. The narrative is often so riveting that a reader desiring a deeper engagement with subject matter will be left disappointed. The book is thoroughly researched, yet so much of the factual evidence presented is referenced by a single line in the notes section rather than with a detailed citation. Similarly, the images are predominately drawn from the Fairfax and Bauer archives, yet without any further details to allow a reader to trace its original context. Reproductions of other works, for example some of Utzon's original sketches held at the State Library of NSW, would also have been valuable. The land now known as Bennelong Point – after the Wangal man, Bennelong – has always been a special place of celebration; since being selected as a site for what is now the world's most recognised performing arts centre, it has been a place of controversy as well. The House takes up celebration and controversy through an engagement with the human toll of the Sydney Opera House. If this story were a work of literature it would surely be found alongside tragedies. Utzon and Arup were unable to mutter more than pleasantries to each other and never recaptured the heady collaboration that resulted in some of the most impressive concrete finishes and self-supporting beams of the era. Hall died a bitter and broken man consumed by a life of public service, hard living and intense scrutiny. Davis Hughes who had carefully manoeuvred Utzon off Bennelong Point, was defiant to the end and Utzon’s life ended without him ever seeing his creation. If we were to seek a happy ending, it is perhaps a miracle that we have an opera house at all. Reviewed by Simon Dwyer, September 2018 Visit the publisher's website here: https://www.allenandunwin.com/browse/books/general-books/history/The-House-Helen-Pitt-9781760295462Categories

John Newton, The Getting of Garlic: Australian Food from Bland to Brilliant

John Newton, The Getting of Garlic: Australian Food from Bland to Brilliant

John Newton, The Getting of Garlic: Australian Food from Bland to Brilliant

NewSouth Books, 352 pp., ISBN: 9781742235790, p/bk, AUS$32.99

John Newtown's new book The Getting of Garlic: Australian Food from Bland to Brilliant is an impressive follow up to his 2016 work The Oldest Foods on Earth: A History of Australian Native Foods. Newton explains in his ‘Introduction, an aromatic absence: or, why I wrote this book’, how, having completed The Oldest Foods on Earth, he “began to wonder about Australia’s non-Indigenous food history”. Curiously, garlic is not noted in Barbara Cameron-Smith’s list of food stuffs brought to Australia with the First Fleet, but garlic seeds are on a list of First Fleet provisions put together by Alan Frost. Certainly garlic “was conspicuous by its absence” in the early modern-Australian diet and recipes. Newton argues, convincingly, that “garlic’s passage from neglect to enthusiastic acceptance tells the story of the changing Australian food culture in a way that no other ingredient does”. With “recipes old and new” this volume, like its predecessor, features numerous meat-based dishes with classics such as Angela Heuzenroeder’s 'Paster Juers’ ‘Roast kangaroo with bacon and garlic’ and Margaret Fulton’s ‘Shoulder of lamb with two beads of garlic’ while ‘Garlic prawns’ make an obligatory appearance. Quite a few seafood dishes are presented (just in time for the summer months and the usually-hot festive season) and a few of the options offered could be easily adapted into vegetarian fare. Garlic doesn't feature in every recipe, and there are also several sweet recipes within the book’s pages, with lamingtons and scones making the cut. Newton explores wide-ranging issues around Australian food culture. The book is not just about a single plant - Newton’s ambition is much grander than that, as he seeks to challenge common conceptions of food and Australian identity. “By the time to you get to the end of this book,” he asserts that you will ask yourself if “there is any point in continuing to slash through the thicket of difference and diversity in search of a single unifying idea that means Australia or Australian.” The Getting of Garlic is a terrific overview of what, for many of us, is now a kitchen staple that is often taken for granted (though, as Newton notes, this species of onion is still routinely avoided by those who find it a little too pungent). Newton’s work, rigorously researched and told with passion, is a history of creativity and of how garlic has gone from an invisible ingredient to being enthusiastically embraced. It is also a story of the joy of “chaotic diversity” and a call to divest of any commitment to seeking a single Australian cuisine. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, September 2018 Visit the publisher's website https://www.newsouthbooks.com.au/books/getting-garlic/Categories

Jacqueline Kent, A Certain Style: Beatrice Davis, A Literary Life

Jacqueline Kent, A Certain Style: Beatrice Davis, A Literary Life (Second Edition)

Jacqueline Kent, A Certain Style: Beatrice Davis, A Literary Life (Second Edition)

NewSouth Books, 347 pp., ISBN: 9781742236025, p/bk, AUS$34.99

Award-winning writer Jacqueline Kent’s highly-acclaimed work A Certain Style: Beatrice Davis, A Literary Life (2018) is now available in an updated second edition from NewSouth Books. Beatrice Deloitte Davis (1909-1992) was a formidable force in Australian publishing in the mid-twentieth century. The general editor for the nation’s oldest publishing house, Angus & Robertson, Davis curated and edited literary culture for decades, supporting writers as diverse as Thea Astley, Xavier Herbert, Miles Franklin, Hal Porter and Patricia Wrightson. The striking influence of Davis can still be seen on bookstore and library shelves across the country. In many ways, reading Kent’s work, first published in 2001, is like having dinner with old friends (and the odd, slightly-awkward colleague). There’s the “quiet, dark-haired Queenslander”, Thea Astley (pp. 158-59). The forever complicated and slightly contradictory Miles Franklin who is, as always, in fine (and outspoken) form, declaring: “I may not be a great genius … but nevertheless my tonnage cannot be ignored” (p. 117). With Xavier Herbert, “a bantam rooster of a man with a grating voice” (p. 181), also there vying for attention. Dominating conversation from the head of the table is, of course, Davis. The fabulously talented editor could be bossy, intimate, stubborn. A pianist who was fond of the odd glass of whisky, Davis’ fierce intelligence was always on display. Davis was, too, a gracious and generous mentor but also a stickler for her own construction of literary traditions: she quickly shunned pieces that included too much sex or too much vulgar language. A running theme, underneath the dull roar of conversations and differences of opinion, is the history of Angus & Robertson. The extraordinary story of an iconic Australian publisher with all of its glories and its many failures (the company, founded in 1886, exists today only as an online store owned by Booktopia and as an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers). Much has already been said of Kent and her telling of Davis’ story, with the first edition claiming both the National Biography Prize and the Nita B. Kibble Literary Award in 2002. What is critical to reiterate in this review, is that women are too often forgotten by biographers and historians. To have Beatrice Davis here again, front and centre, is a wonderful achievement for both author and publisher; it is terrific to be reminded of Davis’ contributions to Australian cultural life and of how she “was the kind of woman who hardly seems to exist in Australia anymore” (p. viii). Beatrice Davis made a difference. It is a pity that the work is not illustrated. There is, however, a new introduction and a very useful index. A Certain Style is a striking narrative. For students and scholars of Australian literature this biography is essential reading and, for those who do not own the first edition, it is destined to be a favourite volume in many personal libraries. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, September 2018 Visit the publisher's website here: https://www.newsouthbooks.com.au/books/certain-style-2nd/Categories

Adam Courtenay, The Ship That Never Was: The Greatest Escape Story of Australian Colonial History

Adam Courtenay, The Ship That Never Was: The Greatest Escape Story of Australian Colonial History

Adam Courtenay, The Ship That Never Was: The Greatest Escape Story of Australian Colonial History

HarperCollins Publishers (ABC Books), 323 pp., ISBN: 978073333857, p/bk, AUS$29.99

In a genuine example of fact is stranger than fiction, journalist Adam Courtenay's book The Ship That Never Was takes us on the gripping journey of James Porter; a man who could quite easily take out the title of Australia’s most roguish lad. Porter’s story starts out in a way that is not too different from so many convict stories of the early-nineteenth century. He is done for stealing (in this case a stack of beaver furs) and dispatched to the far side of the world. In Van Diemen’s Land, Porter’s story is revealed as being a bit different to most as, with far more confidence than the average convict, he takes extraordinary risks from pranking – he advises humourless colonial officials that he is a “beer-machine maker” (p. 10) – through to thefts and then made multiple escape attempts. Porter took “the duty of every recalcitrant who swore the prisoner’s motto: death or liberty” very seriously (p. 8). Sent to the notorious Macquarie Harbour, Porter worked alongside a ragged group of fellow convicts on a ship that was being constructed to transport the prisoners to a new penal station: Port Arthur. In one of the boldest escapes in Australian history, Porter led a group of men to steal the ship and sailed off. The ridiculous, and poorly thought-through plan succeeds and the rough-and-ready crew make it, incredibly, all the way to Chile. But that is not the end of the story. Courtenay has a great talent for bringing dead men back to life. For example, Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur is clearly a difficult person rather than just an historical figure when Courtenay describes him as having “the look of a man mildly appalled at everything he surveyed” (p. 28). Similarly, Courtenay’s summary of Alexander Maconochie’s achievements, though quite brief, presents the former prisoner of Napoleon Bonaparte and later a superintendent of Norfolk Island as not just a noted prison reformer but, rather, as an extraordinary human being who was decades ahead of his time (pp. 299-302). Courtney saves the bulk of his effort for Porter. Indeed, his admiration and his sympathy for Porter is quite pronounced with repeated references to his spunk and his tolerance for physical pain alongside his glossing over of some of Porter’s more dreadful deeds, including the abandonment of his young wife and family in South America. Written as creative non-fiction, the work speeds along. It is well researched (though I would not have listed Marcus Clarke’s 1870s story For the Term of His Natural Life as a primary resource) and, as the Acknowledgements reveal, the project was supported by a strong and skilled team. A disappointment for researchers are the picture captions throughout the text that offer descriptions of, rather than information about, the image (the absolute briefest of picture credits are listed on the copyright page rather than with the image or the acknowledgements; most people would find the detail provided insufficient to locate the original). The volume also lacks an index which would have made the book a more useful resource. The Ship That Never Was is however a fast-paced and fascinating tale. It's a great entry point for people reading about colonial Australia for the first time, as well as an informative read for those who are more familiar with Australia’s modern beginnings. Reviewed by Dr Rachel Franks, September 2018 For a preview of the book visit the HarperCollins website https://www.harpercollins.com.au/9780733338571/the-ship-that-never-was-the-greatest-escape-story-of-australian-colonial-history/Categories

Devonshire Street Cemetery

Devonshire Street cemetery prior to demolition, showing the headstone of Joseph Leburn c1905, by Ethel Foster, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ON 146/no 401)

Devonshire Street cemetery prior to demolition, showing the headstone of Joseph Leburn c1905, by Ethel Foster, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ON 146/no 401)

Devonshire Street Cemetery 1902, courtesy State Archives and Records NSW (17420_a014_a0140000258)

Devonshire Street Cemetery 1902, courtesy State Archives and Records NSW (17420_a014_a0140000258)

Categories

Life and death in Sydney’s early hospitals

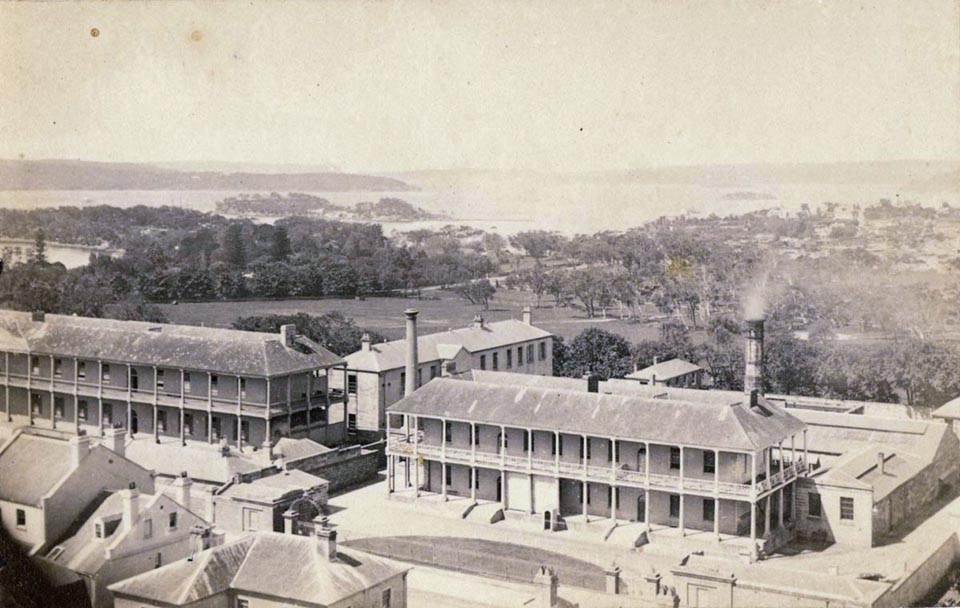

Panoramic view of Infirmary and Mint, Macquarie Street, Sydney c1870, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (SPF/321)

Panoramic view of Infirmary and Mint, Macquarie Street, Sydney c1870, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (SPF/321)

Nicole Cama is a professional historian, writer and curator. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Nicole!

Listen to the podcast with Nicole & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Dictionary of Sydney has no ongoing operational funding and needs your help. Make a tax-deductible donation to the Dictionary of Sydney today!

Nicole Cama is a professional historian, writer and curator. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Nicole!

Listen to the podcast with Nicole & Tess here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

The Dictionary of Sydney has no ongoing operational funding and needs your help. Make a tax-deductible donation to the Dictionary of Sydney today!Categories

The Electrical Association for Women

Electrical Association for Women Cookery Book, compiled and published by Mrs FV McKenzie, Director of the Electrical Association for Women (Australia) Sydney, published by The Electrical Association for Women (Australia), Sydney 1936 (private collection)

Electrical Association for Women Cookery Book, compiled and published by Mrs FV McKenzie, Director of the Electrical Association for Women (Australia) Sydney, published by The Electrical Association for Women (Australia), Sydney 1936 (private collection)

Listen to Lisa and Tess on 2SER here

Electric street lighting was first introduced to Sydney's streets in 1904, courtesy of Sydney Municipal Council and the Sydney Electric Power Station at Pyrmont (now part of the casino). A number of public and private power stations rapidly developed to supply domestic power to suburban Sydney, such as the Balmain Electric Light Company, the Electric Light and Power Supply Company, and the NSW Tramway and Railway Commissioners, who built the Ultimo Power Station and the White Bay Power Station. Domestic consumption grew in the 1920s as electric lighting in the home was enthusiastically taken up, but there was some uncertainty about the safety and uses of electricity for other purposes, and in 1934 an educational association was founded in Sydney by Florence Violet McKenzie to promote the use of electricity to make women's household work easier - it was the Electrical Association of Women (Australia). A similar association had been founded in Britain ten years earlier. No doubt this was the inspiration for McKenzie, a pioneering female electrical engineer and leader in radio communications and signalling. She is one of 200 amazing Australian women profiled in Heather Radi's book 200 Australian Women: A Redress Anthology, (Women's Redress Press, Broadway, NSW, 1988), and of course, we have a great biography of her on the Dictionary of Sydney, written by Catherine Freyne. McKenzie believed in the empowerment of women and the E.A.W. had feminist underpinnings. It was "an Association formed by women to provide for the electrical needs of women". (E.A.W. Cookery Book, p.12), aiming to instil "complete confidence" in the "safe handling" of electrical appliances. The association was non-profit. Women could become members of the Association for a modest annual subscription, and use the club rooms. These were originally located in King Street, Sydney and later moved to the corner of Clarence and Grosvenor Streets, down near Wynyard Station. As well as having a Showroom, fitted out with electrical appliances from different manufacturers, the club rooms included a Library, Bridge-room, Tea-room and Electric Kitchen. Women could receive advice on "all electrical matters", attend lectures on the uses of domestic electrical appliances, and have their appliances tested for safety, whether they were members of the association or not. In conjunction with the Association's activities, McKenzie compiled a cookery book with an electrical guide, encouraging women to be bold and adopt a new technology to transform their lives. Published in 1936, this went to seven editions, the last of which was released in 1954 under the auspices of the Sydney County Council. 'Pikelets being made, and everyone must eat their own!', Electrical Association for Women Cookery Book, compiled and published by Mrs FV McKenzie, Director of the Electrical Association for Women (Australia) Sydney, published by The Electrical Association for Women (Australia), Sydney 1936, p 98-9 (private collection)

'Pikelets being made, and everyone must eat their own!', Electrical Association for Women Cookery Book, compiled and published by Mrs FV McKenzie, Director of the Electrical Association for Women (Australia) Sydney, published by The Electrical Association for Women (Australia), Sydney 1936, p 98-9 (private collection)

Categories

The island laboratory

Loir in the laboratory at Rodd Island, Illustrated Sydney News, 21 November 1891, p12

Loir in the laboratory at Rodd Island, Illustrated Sydney News, 21 November 1891, p12

Listen to Nicole and Tess on 2SER here

Rodd Island sits in the middle of Iron Cove within sight of the former Rozelle Hospital and surrounding harbourside suburbs of Drummoyne and Russell Lea. For thousands of years the Wangal people of the Eora Nation used it to gather food and camp. Over time it's been known as Rabbit Island, Snake Island, Jack Island and Rhode Island. In 1842, the solicitor Brent Rodd claimed the island for his family’s recreational use, even building a family mausoleum there, but he never managed to obtain freehold of the island and it became a public recreation reserve in 1879. In 1888, the island was converted into a laboratory when the NSW Premier, Henry Parkes, offered a £25,000 prize (some estimates say $10 million today), to anyone who could devise a biological solution to the rabbit plague that was ravaging the country. The French microbiologist Louis Pasteur sent a team of people led by his nephew Adrien Loir to conduct experiments on the island using chicken cholera on rabbits. Although the disease did indeed kill the rabbits, they also found it killed native animals on the island. Despite their failure to resolve the rabbit problem, the team successfully developed an anthrax vaccine to protect Australian livestock. It led to more than four million animals being inoculated between 1890 and 1894.* For about six months in 1891, the island also acted as a kind of makeshift quarantine station. The celebrated French actress Sarah Bernhardt came to Australia as part of a world tour, accompanied by an extensive menage that included her pet dogs, two small terriers named Star and Chouette. Like the saga of Pistol & Boo in May 2017, the dogs were not allowed into Australia by customs officials and questions were raised in parliament. A solution was offered by the scientist Loir, a fan of Bernhardt's, who offered to house the dogs on the island. According to a letter he wrote that was published in a French newspaper, the Parkes government gave him money towards costs to house the dogs, which included a new carpet, a flagstaff to hoist the tricolour when Bernhardt visited, twelve bottles of Moet and Chandon and an ivory comb for grooming the dogs.* Bernhardt would visit the island on weekends when in Sydney, and she and Loir would apparently drink the champagne on the roof of the laboratory. Rodd Island c1916, Canada Bay Connections, City of Canada Bay Library (Scan000272.jpg)

Rodd Island c1916, Canada Bay Connections, City of Canada Bay Library (Scan000272.jpg)

Categories