The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Celebrating St Patrick's Day in nineteenth-century Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Celebrating St Patrick's Day in nineteenth-century Sydney

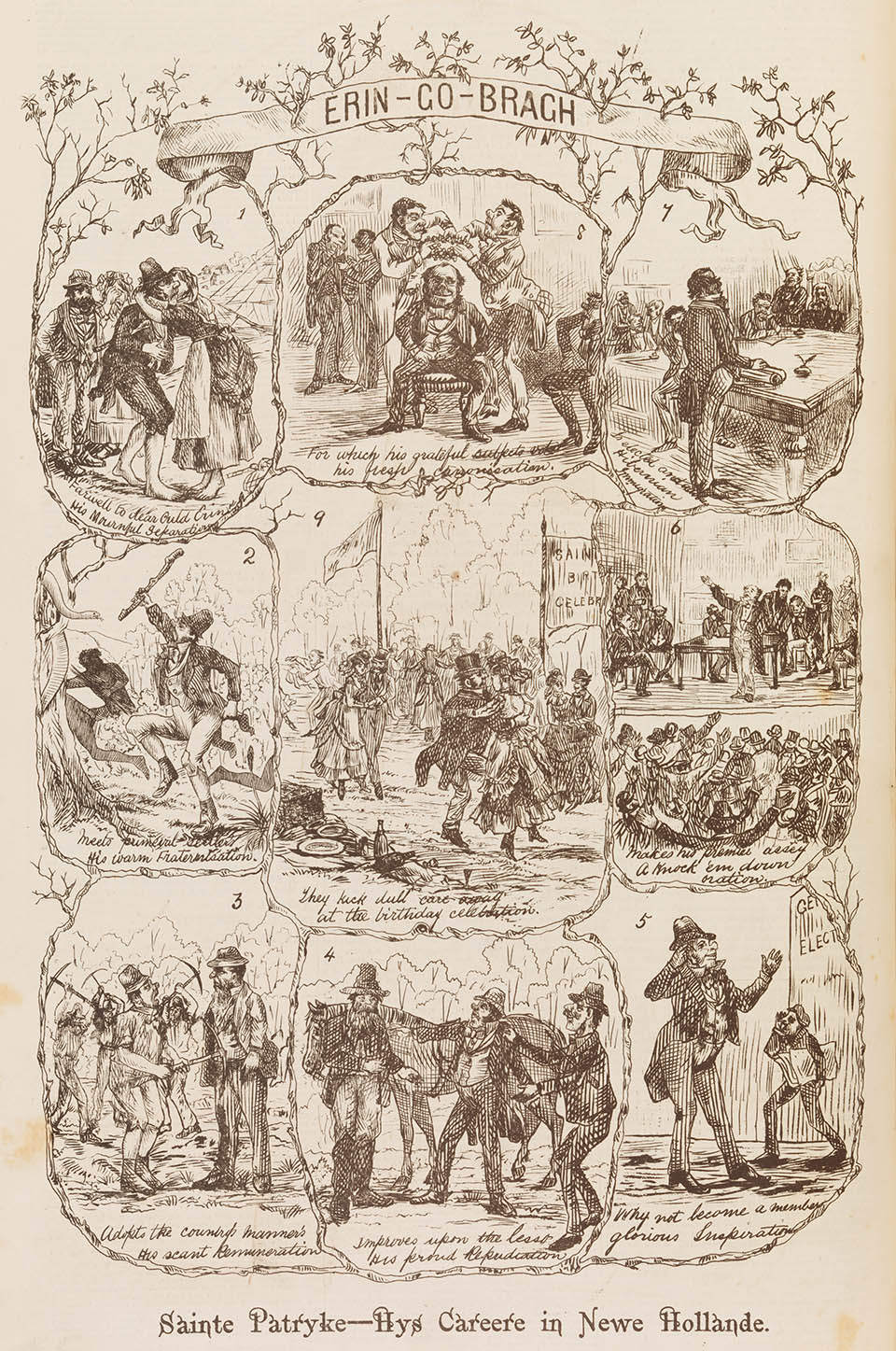

The [media]celebration of St Patrick's Day in Sydney is almost as old as the colony itself. In 1795, Judge-Advocate David Collins wrote in his journal,

On the 17th St Patrick found many votaries in the settlement ... libations to the saint were so plentifully poured, that at night the cells were full of prisoners. [1]

This set a pattern for future celebrations. Governor Macquarie established another when from 1810 he provided entertainments for government artificers and labourers. [2]

In time the public celebration of St Patrick's Day, sometimes dubbed the 'National Hibernian Festival' or 'St Patrick's Festival', would become a major event in Sydney. It extended to various entertainments, including horse races, banquets, parades, picnics, concerts, dancing and games. Nevertheless, it changed in form and tone over the century, often reflecting the change in mood of the Irish citizens of Sydney and their place in the wider community.

Early days

As the number of free settlers increased, the observance of St Patrick's Day became more organised. As early as 1825 the day was marked by a horse race at the new race course on the South Head Road at Bellevue Hill. [3] While the lower classes resorted to the public houses, from 1827 the gentlemen of the colony began to hold dinners to commemorate the day. [4] In 1832 the governor 'honoured the company with his presence'. [5] Thereafter, St Patrick's Day assumed increasing prominence among Sydney's leading citizens as well as the lower classes. The result was that celebrations took many forms, catering to their varied tastes.

Temperance parades and excessive drinking

In 1843 the entertainment included a night-time exhibition of 'two splendid Montgolfier Balloons … the largest ever exhibited in the colony', [6] while the St Patrick's Total Abstinence Society promised a tea party at the Old Court House in Castlereagh Street at which 'the Mayor and his Lady will be present'. [7] Given the stereotype of St Patrick's Day as involving the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol, this might seem surprising. But there was a time when the teetotallers dominated the celebrations.

From 1841 the St Patrick's Total Abstinence Society, a predominantly Catholic organisation, joined forces with the Sydney Total Abstinence Society, a Protestant organisation, to hold on St Patrick's Day an annual procession through the streets of Sydney as a public demonstration in favour of temperance. However, following sectarian rioting in Melbourne during the Twelfth of July celebrations of 1846, the Legislative Council passed the Party Processions Act which banned political and religious processions. Attorney General JH Plunkett took the view that the St Patrick's Day march breached that Act and threatened prosecution. Reluctantly, the temperance societies discontinued their St Patrick's Day parade. [8]

Despite the best efforts of the temperance societies, excessive drinking continued to be a feature of St Patrick's Day. The Sydney Gazette remarked in 1814 on 'the acts of excess and violence into which the lower orders of persons rush' upon St Patrick's Day. [9] The magistrates in the Central Police Court heard many a story of how the day had got the better of an otherwise sober and upright Irishman. In 1859 Patrick Mulhally pleaded guilty at the Central Police Court to assaulting Constable Miller. He told the magistrates that

Thursday, being not only St Patrick's Day, but his own birthday, he indulged a little more freely than he ought to have done. [10]

In 1860 two men admitted to the court that

they had indulged a little before going to church, where they fell asleep, but denied the imputation of having gone there with an Improper motive. [11]

[media]But bad behaviour could be avoided if events were well organised. The Sydney Morning Herald's report on the 1873 St Patrick's Day picnic spoke in glowing terms of the crowd's behaviour:

The colonial Irishman, as seen yesterday at Prince Alfred Park … was so sober and quiet that it would be require the aid of the imagination to associate him with those who partook in the traditional feats at Donnybrook fair. [12]

Sectarian rioting

Scenes reminiscent of the Donnybrook fair did occur in Sydney one St Patrick's Day. In 1878 large-scale rioting broke out in and around Hyde Park. But it may be that the rioting was not so much due to its being St Patrick's Day as to the fact that in 1878 St Patrick's Day fell on a Sunday. The St Patrick's Day riot was but the second round of a bout that had commenced the Sunday before. The occasion for the rioting on both days was a religious service conducted in the park by Pastor Daniel Allen, a Baptist minister and Orangeman. Allen's fiery anti-Catholic preaching was described by the Sydney Morning Herald as

using somewhat violent language … generally calculated to arouse bitter feelings in those differing from him in religious belief.

On 10 March a mob of Catholics drove Allen and his supporters out of the park. The following Sunday, St Patrick's Day, both sides turned out that afternoon in numbers, with a crowd of between 15,000 and 20,000 occupying the park. Many of them had earlier been celebrating the saint's day. Once again the Catholics drove Allen out of the park and down Liverpool Street to his house in Castlereagh Street. All the while much pushing, shoving and stone-throwing took place between rival sections of the crowd. Eventually a large number of police restored order after baton-charging the crowd. [13] As a consequence of these events, Hyde Park was put off limits to provocative speakers, who transferred their activities to the Domain.

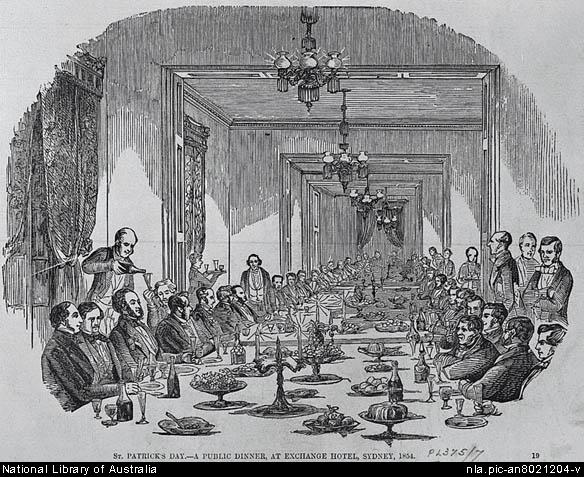

Banquets

[media]Usually the main celebration of St Patrick's Day took the form of a dinner or banquet attended by the city's worthies, including the mayor and leading politicians. These dinners were held under the auspices of various organisations, including Friends of Ireland, the Australian Celtic Association, the Sons of St Patrick or simply 'a meeting of highly respectable gentlemen'. [14] By the 1870s the Hibernian Association was the main organiser of festivities. [15]

In the nineteenth century the banquets were the occasion of loyal toasts and patriotic speeches. This was because acts of rebellion in Ireland often led to a backlash against the Irish in the colony. Those Australian Irish with status who attended the dinners were at pains to demonstrate their loyalty to the Crown. So much so that in 1862, following the death of Queen Victoria's husband Prince Albert, the organising committee decided to dispense with the festivities altogether. Although the prince had died on 14 December 1861, news only reached the colony on 27 February 1862 when preparations for the saint's day were well underway. [16]

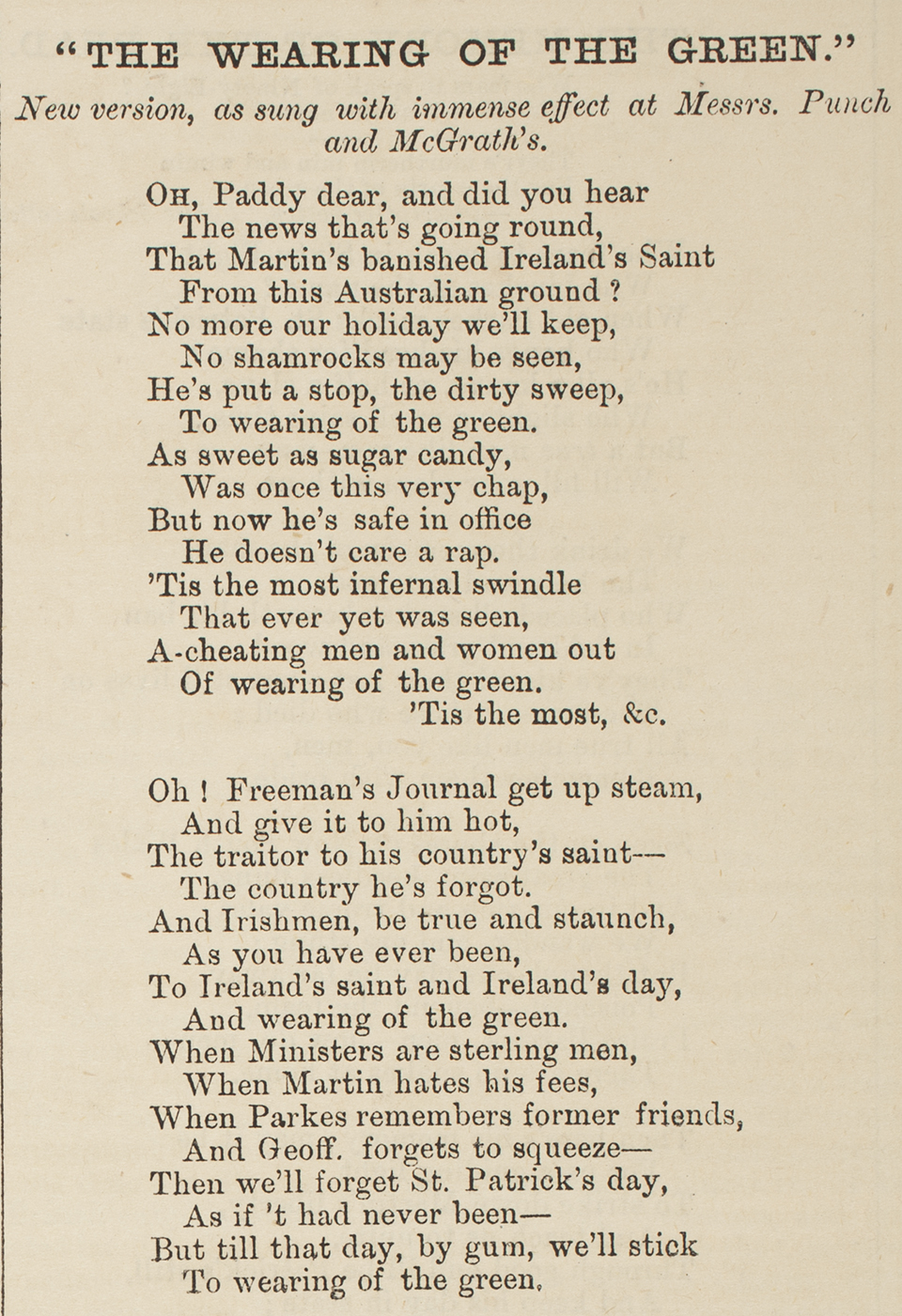

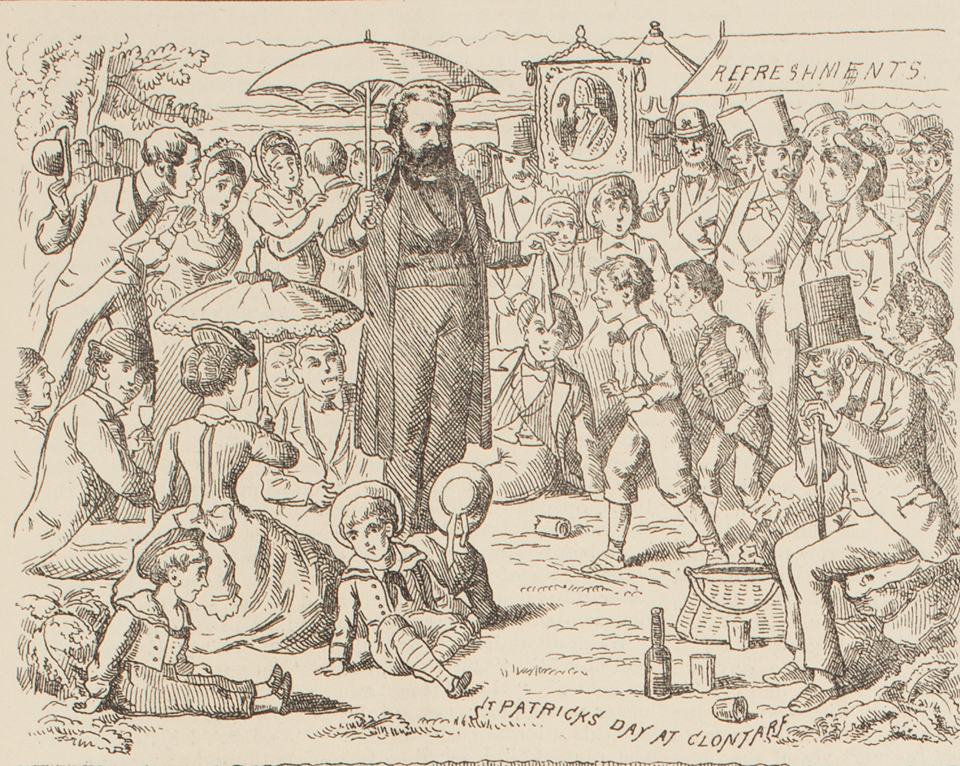

[media]However, not all Irishmen were so obsequious. A week before the 1868 celebrations two members of the organising committee declared that they would not join in the loyal toast to the queen. As a result, the governor, Earl Belmore, withdrew his patronage of the celebrations. Embarrassment over the issue was avoided, however, when the festivities were abandoned for a different reason. On 12 March the deranged Irishmen Henry James O'Farrell attempted to assassinate Queen Victoria's second son Prince Alfred at Clontarf on Sydney's Middle Harbour. [17] The organisers decided that in the circumstances it would be unseemly for the Irish community to be seen celebrating when the prince lay wounded at the hands of an Irishman.

But it was not only the death or wounding of royalty that resulted in the cancellation of St Patrick's Day festivities. In 1877 the organising committee cancelled the day's celebrations following the death of the Catholic archbishop John Bede Polding on 16 March.

From 1864 the grand banquet fell out of favour as the principal form of St Patrick's Day observance. For a few years it was replaced by a luncheon in the saloon of one of the boats taking part in the St Patrick's Day regatta before resuming again in 1879. [18]

In 1882 the St Patrick's Day banquet was held for the first time in the Sydney Town Hall rather than the Masonic Hall, which had been the venue for many years. [19] However, in 1883 the Town Hall was unavailable for the banquet when controversy arose around the guest of honour, John Redmond, an Irish nationalist MP in the House of Commons. Redmond and his brother William were visiting Australia on behalf of the Irish National League. Nationalism was on the rise in Ireland under the leadership of Charles Stewart Parnell. His vigorous agitation for home rule and tenants' rights incensed many in the colony, including some of the more 'respectable' Irishmen. On their journey through the Australian colonies the Redmond brothers often received a hostile reception. But the main controversy that night occurred when the Minister for Works, Henry Copeland, a Yorkshireman, made a drunken speech in which he criticised his own government. His outburst cost him his job. [20]

The Town Hall once more became the venue for the banquet from 1885 and remained so until 1892, [21] when the banquet again fell into abeyance. It gave way in 1896 to a luncheon at the Agricultural Association Ground as part of Cardinal Moran's plans to reform the St Patrick's Day celebrations, discussed below.

Sporting carnivals

From the earliest times St Patrick's Day celebrations included sports of one sort or another. Horse racing was an early and common activity throughout the century. Some years saw a boating regatta on the harbour, such as the Pyrmont Regatta of 1858 held in conjunction with the opening of the Pyrmont Bridge. [22] Regattas were also held between 1864 and 1867. [23] Thereafter, sports days on land became a regular feature of St Patrick's Day celebrations, though in the early 1870s they were not well organised. According to the Herald's account, the 1871 sports carnival was a shambles. Apart from the inclement weather, 'no conveniences of any kind were to be found, not even refreshments to be had for love or money'. [24] However, by 1885 the sporting component of St Patrick's Day had become well established, with sporting events conducted at the Agricultural Societies Ground, Prince Alfred Park or Chowder Bay – sometimes all on the one day. [25] Sir Joseph Banks Park at Botany was another popular venue for games of all sorts as well as dancing.

Concerts

Another form of entertainment that soon became well established was the St Patrick's day concert. It was originally held in an available hall and comprised a limited repertoire. But by the mid-1890s it had become a major cultural event held at the Sydney Town Hall and attracting a sizeable audience.

Parade

[media]The Party Processions Act had seen the demise of the St Patrick's Day parade in 1847. However, in 1880 the Hibernians marched from St Benedict's, Broadway to Circular Quay to catch the ferry to Chowder Bay for the St Patrick's Day picnic and sports. [26] The authorities made no attempt to prevent the march and thereafter the St Patrick's Day parade became a feature of the celebrations for many years. From 1885 the procession went from St Benedict's along the city's major streets before embarking on trams for Sir Joseph Banks Park, Botany for a picnic and sports carnival. [27]

By the end of the 1880s the parade had broadened its appeal to a wide variety of Irish societies. The Herald estimated that the 1888 procession 'was made up of 3000 members of societies, and extended for about three-quarters of a mile' as it wound its way from St Benedict's along George Street to Bridge Street, ending at Bent Street. [28] The march by a combination of Irish societies, their banners proudly displayed, continued uninterrupted until 1895.

In that year the parade was cancelled because of the death in office two days before of the governor Sir Robert Duff. [29] Then, later that year, Cardinal Moran took control of the organisation of the St Patrick's Day celebrations. He disapproved of the parade's overt display of Irish nationalism and the procession was dropped. [30] However, in 1899 it reappeared, but with a religious rather than a political theme. Commencing at St Mary's Cathedral and winding its way to the agricultural ground at Moore Park, the procession comprised members of various Catholic guilds as well as students from Catholic primary schools carrying several banners. [31]

Picnics

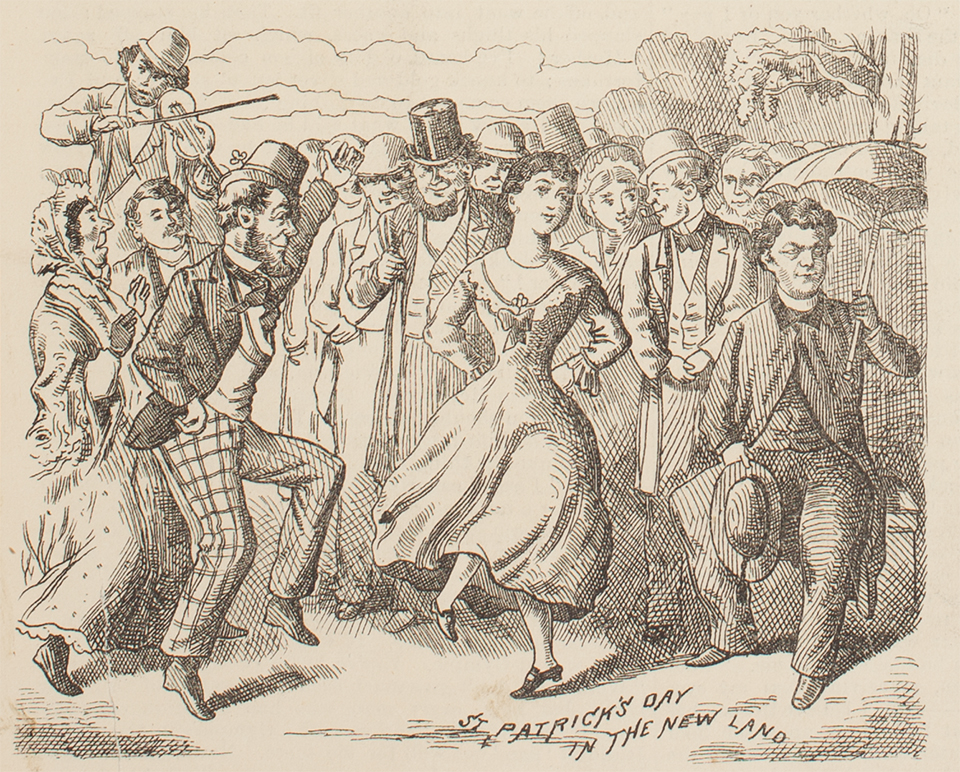

[media]By far the most popular form of celebration of St Patrick's Day was the picnic. From 1869 picnics were held at various locations around the harbour, including Balmoral, Clontarf, Athol Gardens and Chowder Bay, or at city parks, such as Prince Alfred Park, or at the Sir Joseph Banks Park, Botany.

In the early years, the picnics were attended by leading citizens, including government ministers, as well as by ordinary folk displaying shamrocks and green rosettes and ribands. Picnics soon began to attract thousands of revellers who were transported to the harbour picnic spots by ferry.

[media]Sports were often held at these [media]picnics as were Irish music and dancing. Sometimes in the evening there was a ball or a banquet or a musical concert or a theatrical performance. Sometimes, as in 1874 the day included all of these forms of celebration combined. [32] From the mid-1880s it became the norm for many different types of [media]functions to be held in Sydney on St Patrick's Day.

[media]From 1883 the picnic took on a distinctly political tone. In that year it was held at Botany and organised by the Irish National League. The main guest was the Irish nationalist MP John Redmond. [33] For more than a decade, while the issues of Irish home rule and land agitation were being debated 'at home', the Irish National League used the occasion to hold a political rally in conjunction with the Botany picnic. Money raised on the day was sent to Ireland, initially for the support of Irish MPs in the House of Commons and later for the evicted tenants' fund.

Those less politically inclined continued to hold their picnics at one of the harbourside picnic grounds, but they were the minority. The Herald estimated that in 1886, 6,000 were at Botany and only 2,000 at Chowder Bay. [34] In 1887 the number at Botany was said to be 15,000. [35]

In that year a controversy erupted in relation to the Botany picnic when the newspapers reported that a call for three cheers for the queen was met with groans. Questions were raised in parliament and letters published in the newspapers. However, it is unclear whether the groans were meant for the proposal or for the proposer, the soon-to-be notorious Paddy Crick. [36]

Political speeches, which had been a prominent part of the Botany picnic, were notably absent in 1891. The previous November the Irish Parliamentary Party had split following disclosure of Parnell's adultery with Kitty O'Shea, the wife of one of his parliamentary colleagues. Both in Ireland and throughout the diaspora Irish men and women were deeply divided over the issue. To avoid exacerbating those divisions the management committee decided to dispense with the usual speeches. [37] Speeches soon resumed at Botany but the speakers were careful to avoid the divisions that would remain in the Irish national movement until the new century. For more than a decade, St Patrick's Day had a distinctly political flavour, but in 1895 that came to an end.

St Patrick's Day transformed

In 1895 Cardinal Moran acted to take control of the [media]organisation of Sydney's St Patrick's Day celebrations and to introduce what the Herald described as

an entirely new departure from the methods formerly adopted for the commemoration of Ireland's national holiday. [38]

This would involve moving the venue of the picnic to the Agricultural Association Ground, placing the sports under the control of the New South Wales Athletics Association, stripping the celebrations of any political significance and devoting the proceeds entirely to local charitable causes. Voicing its approval of the changes, the Herald reported that the official estimated attendance was 10,000. [39] A small number of people resorted to the traditional picnic spots on the harbour and at Botany, but their numbers were insignificant compared to those who attended the official event. [40]

Under Moran's tutelage, St Patrick's Day was transformed from an Irish nationalist and Irish political day organised by the lower classes, into an occasion 'for the demonstration of Irish Catholic power and respectable assimilation to the general public' as well as 'for the affirmation of Irish Catholic solidarity'. [41] To Moran, dissension among the Australian Irish was the work of 'a few evil-designing persons' and something to be stamped out. [42] He made it his job to do so.

Moran began the process soon after his arrival in Sydney in September 1884, by inaugurating the celebration of a solemn High Mass in St Mary's Cathedral on St Patrick's Day 1885. The Sydney Morning Herald estimated the congregation as being between 4,000 and 6,000. [43] Ten years later the cardinal had assumed full control. The St Patrick's Day luncheon became a symbol of the new prestige which Moran sought to bring to the day: the cardinal was in the chair presiding while seated on his right was the governor. [44] In 1899 the lieutenant-governor and the premier were the principal guests along with a host of other dignitaries. [45]

In 1900 the government proclaimed St Patrick's Day a holiday in Sydney in deference to the Queen Victoria's recognition of the bravery shown by the Irish regiments in the South African war. [46] As a result, the crowd attending the Agricultural Ground was estimated to be between 15,000 and 17,000. [47] This kind of recognition by the state of the significance of the Irish saint's day was precisely what Cardinal Moran had sought in taking control of the celebrations.

But this was not the first time St Patrick's Day had been a public holiday in Sydney. It had been so from 1864 to 1867. [48] And for many years previously it had been a bank holiday. [49] In fact the first bank holiday on St Patrick's Day was proclaimed in 1823. [50] In 1858 it was declared a 'partial holiday' in connection with the opening of the Pyrmont Bridge when 'amusements of all kinds took place in and about the city'. [51]

In 1868, however, the government decided against proclaiming the day a holiday. This led to complaints that workingmen would be unable to attend the regatta, which was then the principal means of celebrating the day. As a result, a committee of Irishmen decided to hold a ball at night to mark the day. [52] However, both the ball and the regatta were abandoned because of the shooting of Prince Alfred. [53] While the citizens of Sydney had to wait until 1900 to regain a day off work on St Patrick's Day, numerous towns throughout the state continued to observe a holiday on that day.

When in 1900 the government restored the holiday in Sydney the premier warned that the proclamation should not be regarded as a precedent. [54] Nevertheless, St Patrick's Day was declared a holiday in 1901 and 1902. But that was as far as it went. In 1903 commercial interests and militant Protestants suspicious of Moran's growing influence with the government persuaded the premier to bring the holiday to an end. [55]

Conclusion

Throughout the nineteenth century the citizens of Sydney had observed St Patrick's Day with much enthusiasm. Only on rare occasions, such as the death of a prince, a bishop or a governor or the wounding of royalty, did the day pass without some form of public celebration.

Over the course of the century the celebration took various forms: banquets, picnics, regattas, sports carnivals, concerts and so on. Often the day was packed with a combination of such activities. Not to be forgotten, of course, is the religious service – after all, the day was set aside to commemorate a Christian saint. From very early on the day started with a Mass at St Patrick's Church Hill and then later solemn High Mass at St Mary's Cathedral.

Over time the focus of the celebrations changed. In some years the principal event was a grand banquet; in others a regatta or a picnic. The tone of the day changed also. Up to the 1830s it was ad hoc but from the 1830s it became organised. In the early 1840s the temperance societies dominated, then the leading citizens with their banquets and regattas, then the hoi polloi with their picnics, then the Irish nationalists with their speeches and parades. And, as the century came to a close, the tone of the celebrations changed once more. After Cardinal Moran stepped in, St Patrick's Day became strongly identified with triumphalist Irish Catholicism.

But as with earlier incarnations of the day's commemoration, Moran's influence would not last forever. Over the course of the twentieth century and up to the present, St Patrick's Day has continued to display its remarkable ability to adapt and change, ensuring that the feast day of the patron saint of Ireland does not pass unnoticed in Sydney.

References

Patrick O'Farrell, 'St Patrick's Day in Australia', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol. 81, 1994

Mike Cronin and Daryl Adair, The Wearing of the Green: A History of St Patrick's Day, Routledge, London, 2002

Notes

[1] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales, London, 1798, vol 1, ch 28

[2] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 17 March 1810, p 2

[3] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 24 March 1825, p 2

[4] The Australian, 20 March 1827, p 3; Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 20 March 1827, p 3

[5] Sydney Herald, 19 March 1832, p 4; Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 20 March 1832, p 2

[6] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 March 1843, p 3

[7] Sydney Morning Herald, 14 March 1843, p 2

[8] Sydney Morning Herald, 5 April 1847, p 2

[9] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 25 June 1814, p 2

[10] Sydney Morning Herald, 21 March 1859, p 4

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1861, p 3

[12] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1873, p 5

[13] Sydney Morning Herald, 11 March 1878, p 4; 18 March 1878, p 5

[14] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 March 1855, p 5

[15] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1874, p 5; 18 March 1875, p 4

[16] Sydney Morning Herald, 28 February 1862, p 4; 1 March 1862, p 7; 19 July 1862, p 6

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 14 March 1868, p 4

[18] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1879, p 3

[19] Sydney Morning Herald, 21 March 1882, p 7

[20] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1883, p 5; 29 March 1883, p 4

[21] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1885, p 7; 19 March 1886, p 5; 18 March 1887, p 5; 19 March 1888, p 4; 19 March 1889, p8; 18 March 1890, p 5; 18 March 1891, p 8; 18 March 1892, p 4

[22] Sydney Morning Herald, 26 February 1858, p 1; 22 March 1858, p 2; 10 April 1858, p 9

[23] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1864, p 5; 18 March 1865, p 5; 19 March 1866, p 5; 19 March 1867, p 5

[24] Sydney Morning Herald, 25 March 1871, p 4; 31 March 1871, p 5

[25] Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 1885, p 8; 18 March 1885, p 7

[26] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1880, p 5

[27] Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 1885, p 8; 18 March 1886, p 6

[28] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1888, p 4

[29] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1895, p 6

[30] Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 1896, p 6

[31] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 March 1899, p 3

[32] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 March1869, p 5; 31 December 1870, p 4; 16 March 1871, p 5; 19 March 1872, p 4; Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1873, p 5; 18 March 1874, p 5; 18 March 1875, p 4; 18 March 1876, p 4

[33] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1883, p 5

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 March 1884, p 11; Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 1885, p 8; 18 March 1886, p 6

[35] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1887, p 5

[36] Sydney Morning Herald, 24 March 1886, p 4; 25 March 1886, p 7; 27 March 1886, p 10

[37] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1891, p 8

[38] Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 1896, p 6

[39] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1896, p 5

[40] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1896, p 6

[41] Patrick O'Farrell, 'St Patrick's Day in Australia', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 81, 1994, p 11

[42] Sydney Morning Herald, 12 March 1900, p 8

[43] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1885, p 7

[44] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1896, p 5

[45] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 March 1899, p 3

[46] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 March 1900, p 4

[47] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1900, p 3

[48] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 March 1864, p 5; 18 March 1865, p 5; 19 March 1866, p 5; 9 March 1867, p 7 (observed on Monday 18 March)

[49] See, for example, Sydney Morning Herald, 17 March 1858, p 1; 16 March 1859, p 1

[50] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 13 March 1823, p 1

[51] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 April 1858, p 9

[52] Sydney Morning Herald, 26 February 1868, p 4

[53] Sydney Morning Herald, 14 March 1868, p 4

[54] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 March 1900, p 4

[55] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 March 1901, p 9; 12 March 1902, p 13; 12 March 1903, p 8