The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

River Cycles - A History of the Parramatta River

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

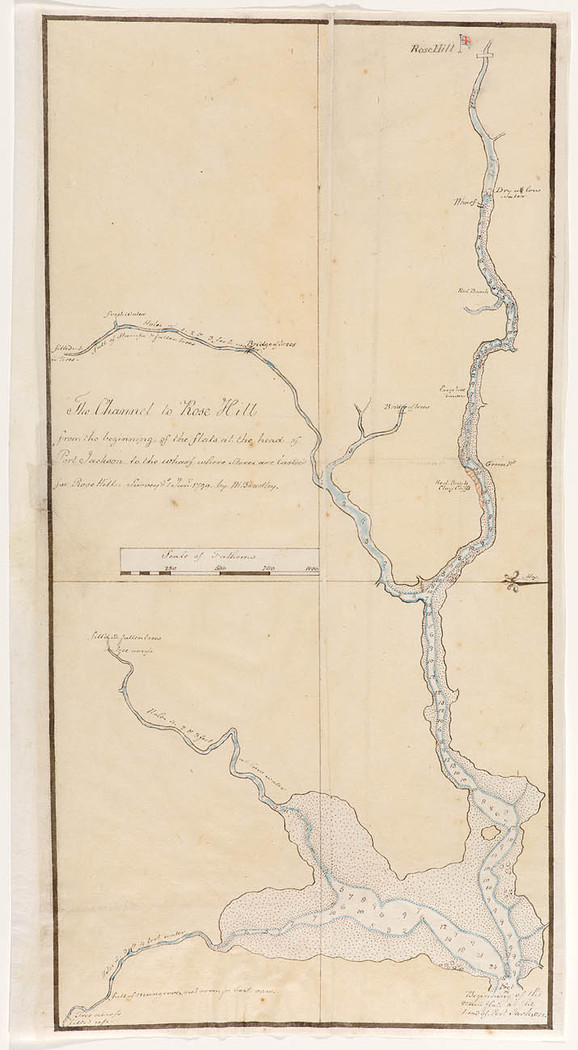

From freshwater river to estuary

[media]The water course we know as the Parramatta River was created 15 to 29 million years ago as water began to cut a valley into sandstone and shale laid down some 200 million years earlier. When the river began its flow, Australia had separated from Antarctica and begun moving north. The climate changed many times over the millennia. Some 10,000 years ago, the valley that had formed began to fill with rising seawater unleashed from melting glaciers to shape Sydney Harbour. Today, most of the river to west of the city of Sydney is considered to be part of the harbour, all the way up to Parramatta where the tidal brackish water stops and fresh river water flows east fed by the Domain Creek and two other courses at the river's head; the Darling Mills and the Toongabbie Creeks.

This freshwater river runs for just over a kilometre. The remaining tidal waterway that is part of Sydney Harbour is estuarine. Here fresh and salt water mixes in varying proportions, dependent upon rainfall, run-off and tide, for the 20 kilometres east to Manns Point on the harbour's north shore and Longnose Point on the south. These protrusions mark the beginning of the river. The latter forms a barrier to the more extreme wind and swells so that, in the words of the historian PR Stephensen, 'to the westward…the waters are so fully landlocked that their smoothness could never be disturbed by more than local ripples'. [1]

From this easterly point to Homebush Bay, the river resembles a harbour as its many bays create a wide waterway containing three islands: Cockatoo, Snapper and Spectacle. By contrast, from Homebush Bay to Parramatta, the river is a serpentine shallow, narrow channel increasingly flanked by mudflats and mangroves. For many years it was thought this growth represented the river's natural foreshore ecological community; that which existed prior to European modification of the landscape from the early nineteenth century. The first colonial accounts referred often to mangroves. It was in the upper stretch in the 1790s that the colony's first master boat builder, Daniel Paine, obtained the mangrove wood which was 'very useful for cutting into Boats timbers growing in every shape proper for the purpose'. [2]

More recent studies, however, have suggested that saltmarsh covered much more foreshore than is currently the case, particularly on the flatter southern side; while casuarinas, melaleucas and eucalypts grew down to a hard water's edge elsewhere. The prevalence of mangroves today is thought to be result of landscape change rather than remediation, in particular the siltation that has resulted from land clearing. [3] Saltmarsh, by contrast, is an endangered habitat.

The Indigenous river

Four Indigenous groups occupied the land surrounding Parramatta River. For the Wangal people, whose traditional territory extended along the southern side from Darling Harbour (Tumbalong) to Parramatta, salt marsh provided access to waterbirds for which it was a crucial habitat. At high tide crabs could be caught and fish might be easily speared there. Ducks also inhabited the creeks that fed the river. The waterway itself was an important source of food for Indigenous people. Bennelong, best known of the Wangal because he befriended the first governor, Arthur Phillip, was a skilled fisherman. Fish and shellfish were no less important for the Wallemudegal who occupied the opposite shore. The clan name is thought to relate to the Wollomy, or Snapper fish. [4] That species was either a prized catch or spared as a totemic animal. Bream, mullet and flathead were certainly caught. Manns Point was at the western end of Gammeraygal land. They, too, occupied the foreshores with women in bark canoes fishing with bark string line and shell hooks and men spearing fish near the shore.

[media]Two species of eel, Anguilla Australis and Anguilla Reinhardtii, are known to migrate between the freshwater of the river and the sea. The Burramattagal took their name from the place where these eels swam at the headwaters of the river. And that, in turn, gave rise to the name of the second European settlement, 'Parramatta', and therefore the name of the river itself. Today the Parramatta River runs through the middle of the Eora nation of 29 Aboriginal clan groups, a territory bounded by other waterways, the Hawkesbury, the Nepean and the Georges rivers.

The colonised waterway

For Indigenous people the river was a shared food source, a highway and a territorial boundary. For the British who claimed the coast in 1770, and returned to occupy it in January 1788, the waterway was first a means of exploring the 'new' country west of Sydney Cove. The naval men among them recognised it as an extension of the harbour rather than a river, a term they reserved for freshwater channels.

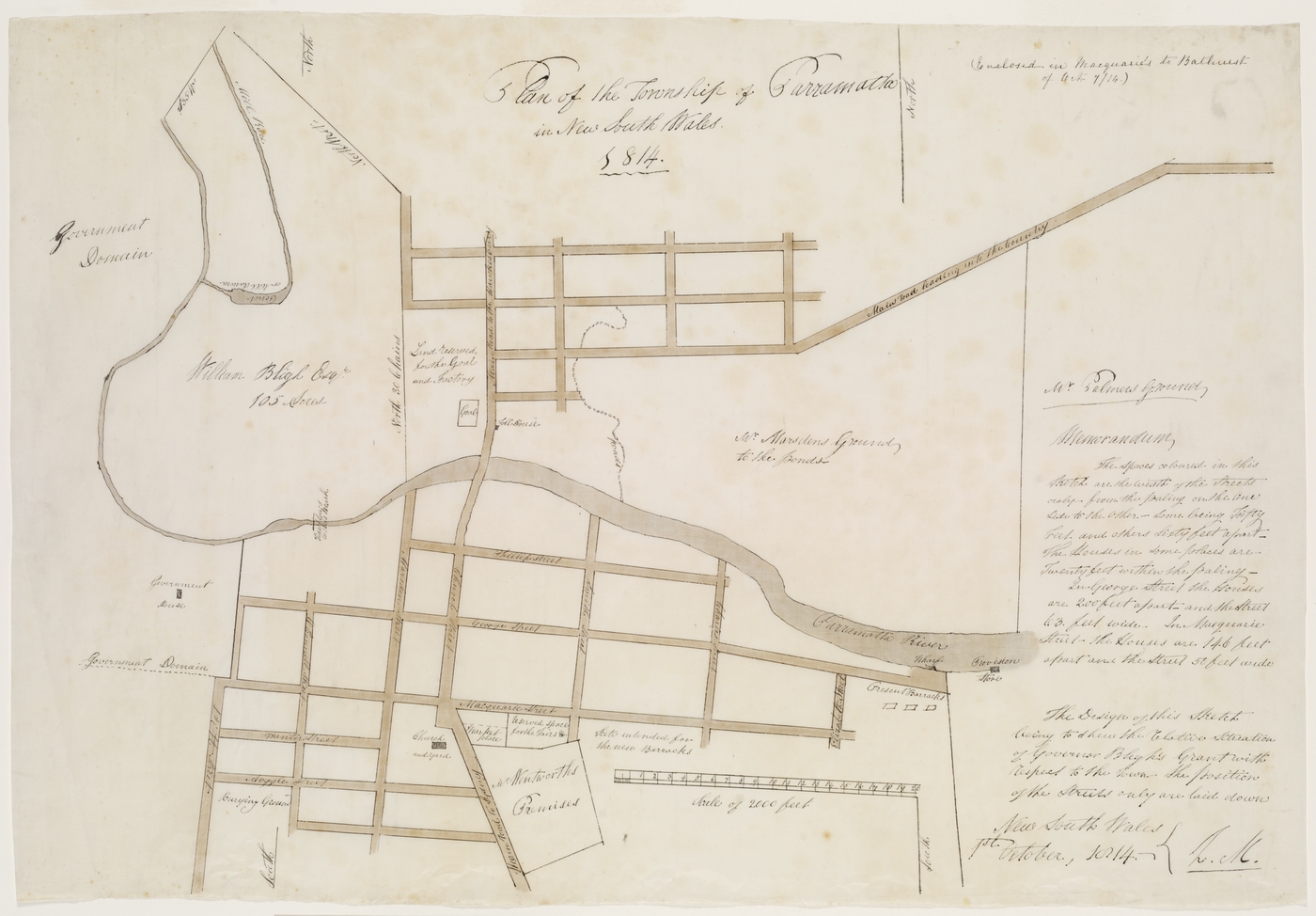

Governor Phillip regretted his decision to establish the first settlement at Sydney Cove, with its barren sandy soil, and began construction of a second settlement at the more fertile, well-watered 'head of the harbour' as early as November 1788. Known initially as Rose Hill, it was called Parramatta in June 1791. The name was applied to the river which led to the town by the end of the decade.

Parramatta was, however, one of the few Indigenous names to be retained along the waterway. Most others referred either to landmarks, such as the rock formation Pulpit Point, or the properties established along the banks – such as Homebush and Abbottsford. Other sites refer to the people who came to own the land; for example Clarkes and Manns Point. Still other names, Greenwich, Woolwich, Henley, Putney and Mortlake, were taken from places along the Thames River and indicate the strong Anglophile sentiments of the colonists.

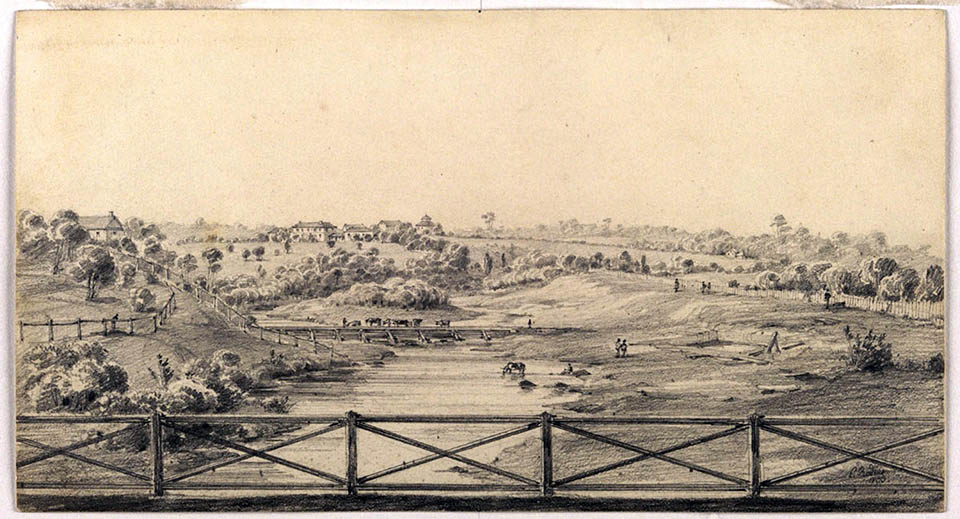

[media]Modification of the riverine landscape began as early as 1791 with the planting of a vineyard on the upper river next to a freshwater tributary now called Vineyard Creek. Citrus trees followed the next year. The trees flourished there and elsewhere. Somewhat poignantly it was amid the introduced fruit trees – the orchard of James Squire at Kissing Point on the eastern end of the river – that the Wangal man Bennelong was buried in 1813. The traditional land of his people lay on the opposite side of the river. By then the social structure of all the harbour clans had been profoundly altered. As early as 1793 the colony's first free immigrants were granted land to farm on Wangal land at Liberty Plains – around present-day Homebush Bay. By the 1830s wetlands there were being drained and filled in to create firm and arable land. [5]

[media]A Government House was begun on the banks of the freshwater river in 1788. Between 1812 and 1818 the aesthetically-minded Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie incorporated the river into their landscaping of the house grounds, the Governor's Domain. Part of this domain with its stretch of water became a public place, Parramatta Park, in 1857.

[media]The first river ferry, the Rose Hill Packet, was launched in 1789. Despite the creation of a track linking the Sydney and Parramatta settlements by 1791, and a railway in 1855, the river remained significant throughout the nineteenth century both for access and aesthetic appeal. An auction advertisement in the Sydney Gazette of 14 August 1803 for a dwelling and bakehouse 'on the Bank of the Parramatta River' made a selling point of the fact that 'a boat can come close to the bottom of the garden'. The best surviving example of river front aspect is the Thomas Walker Convalescent Hospital built in the 1890s on the estate Yaralla of the wealthy philanthropist after whom it was named. A large turreted waterfront gatehouse greeted those who arrived by water.

River travel

Wind and tide were critical in the first 30 years of river travel. Against the elements, a journey to Parramatta could take 12 hours or more, leaving the ferrymen exhausted from working the oars. The first paddle steamer built in the harbour serviced the Parramatta run shortly after its launch in 1831. Others followed and from 1838 the Steam Packet Hotel advertised rooms at the newly-named Queens Wharf on the busy Parramatta River head.

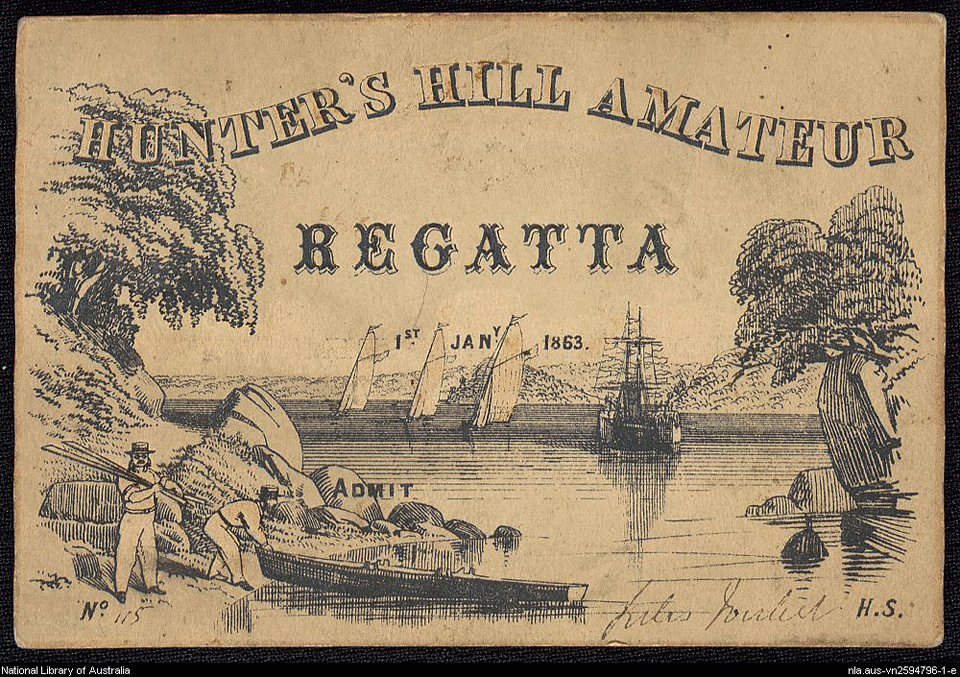

To the east the enterprising Joubert brothers knew that water transport was critical to the success of the salubrious riverside suburb of Hunters Hill they had started to develop in the 1850s, and so they established their own ferry service between there and the town in 1860. The service expanded to several vessels and became a revenue stream in its own right.

Siltation and shallowing was such that the ferry service all the way to Parramatta was withdrawn in 1928. It was not reinstated until 1993 when the purpose-designed catamaran ferries, dubbed RiverCats, were introduced by the government-run State Transit Authority which then operated all the harbour ferry services. The new ferries were immediately successful and have since catered for a growing demand for river travel as more housing developments have been completed along the waterway. However, while dredging in the 1990s had made the upper river accessible, the service there would again become dependent upon tidal access with ever more frequently ferries terminated at Rydalmere east of Parramatta. Because of this, and the environmental effect of wash upon the river bank, the Report of the Special Commission of Inquiry into Sydney Ferries Corporation in 2007 recommended a discontinuation of services to this upper stretch while acknowledging the likelihood of greater ferry use on the lower river. The tide dependent service was, nonetheless, maintained after operation of Sydney's ferries was contracted to the private franchisee Harbour City Ferries in 2012.

From highway to obstacle

[media]What was a watery highway for some was, of course, an obstacle to be crossed for those who needed to move between north and south banks. The first span over the estuarine river was built at Parramatta before 1795. That was destroyed in a flood and replaced by another around 1803. The third span on the site was completed in 1839 and named after its designer, David Lennox, the Superintendent of Bridges. [6] The Lennox Bridge survives as the oldest 'Harbour Bridge'. Two others followed before the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932. The iron lattice Gasworks Bridge was completed near Parramatta in 1885 and similar structure, the John Whitton Bridge, was built between Rhodes and Meadowbank in 1886 to cater for trains travelling from Hornsby to the city. Elsewhere punts provided river crossing for horse and vehicular traffic.

[media]The crossings built in the twentieth century were indicative of the growing, and ultimately the overwhelming, significance of road transport. The Ryde Bridge was completed in 1935, the Silverwater Bridge in 1962 and the Gladesville Bridge in 1966. The latter was part of the multi-lane North Western Expressway project and, when completed, was the largest single span concrete arch ever built.

A sporting river

The Burramuttagal people surely swam and played in the freshwater stretch of the river, though they may have been warier of the brackish water to the east, for bull sharks almost certainly frequented the upper river then as they do today. Europeans, too, swam in the freshwater well into the twentieth century. A sandy beach on the river bank was named Little Coogee after the more famous beach in Sydney's eastern suburbs. At least six swimming and bathing enclosures were built along the estuary between 1904 and 1932.

[media]Competitive rowing – sculling – was also extraordinarily popular in Sydney in the late nineteenth century. The sheltered waters of the riverine harbour, protected by Longnose Point, offered the ideal place for competition which was both amateur and professional. The Sydney Rowing Club, founded by gentlemen amateurs in 1870 near the present-day Sydney Opera House, purchased river premises at Abbotsford Point in 1874.

[media]Remarkably, the professional sport was international with local rowers heading overseas to compete and as many as 45 world championship races were held on the river over several decades. The professional prize money was sometimes the equivalent of $100,000 and more in today's terms. Edward 'Ned' Trickett was perhaps the most celebrated as a local boy born near the river at Greenwich who went to England to win the world championship on the Thames in 1876. Henry Searle was another colonial hero; tragedy ended his brilliant career in 1889 when he died of typhoid in Europe having convincingly beaten the Canadian champion on the Thames. A monument to his memory, a white broken column symbolising a life cut short, was erected on a rock in the Parramatta River, appropriately enough near Henley the namesake of the Thames River town most closely associated with rowing since 1839. It still stands today. Another, to the world champion William 'Bill' Beach, was erected on the opposite shore at Cabarita.

Women also rowed competitively, though their prize money was a fraction of that given the men. Several amateur women's rowing clubs were formed in the first three decades of the twentieth century in answer to the general exclusion from membership of established clubs. It was not until 1993 that the Sydney Rowing Club, steeped in tradition, allowed women to become members. [7]

In the eastern river, where the water was not too sheltered, rowers shared the waterway with sailing clubs that sported small skiffs rather than the large yachts that were seen in the eastern harbour. The Balmain Sailing Club was established as early as 1885. The Drummoyne Sailing Club was formed in 1913. The Abbotsford 12 Footer Flying Squadron was founded in 1936, with the Greenwich Sailing Club starting up two years later. The Hunters Hill Sailing Club was established at Onions Point in 1961.

The industrial river

By the time the members of the Hunters Hill Club were launching their sailing dinghies, the quality of the river water had deteriorated dramatically because of run-off and industrial pollution, so that bathing, if not rowing and sailing, was discouraged. Residents and recreational river users had shared the waterway with industry since the mid-1800s. Some industries, such as Rosemorrin copper smelting works at Woolwich, had set up alongside the waterway so that raw materials and product could be easily shipped. Others, like the nearby Atlas Engineering Company, which serviced shipping, were maritime by their very nature.

The size of the nineteenth century river estates was conducive to subdivision and redevelopment when the money, willingness or family ties necessary to maintain their productivity or grandeur had gone. At Mortlake, originally a 74 acre (30 hectare) land grant in 1795, the Australian Gas Light Company [AGL] began producing gas from coal in 1886. Like the Rosemorrin copper smelter, the riverside location was ideal for transportation; in this case millions of tonnes of Hunter Valley coal shipped by collier's that came to be called 'sixty milers' because of the distance they travelled down the coast. By the 1960s the vessels were so large that they waited at Cockatoo Island for the right tide.

At Homebush – the vast Wentworth family estate that had been established in 1811 as a horse stud – the bay was progressively filled in with soil and rubbish. Much of the land was acquired by the government to build an abattoir from 1907 and a brickworks in 1911. Industrialisation attracted illegal dumping and the river assumed a new identity as an open sewer.

Nearby Rhodes was home to the Walker family from the 1820s until 1919 when the property was bought to accommodate a flour mill. Timbrol, which manufactured timber preservative, was established next door in 1928. Carcinogenic pesticides were produced there during the 1940s. After the site was taken over by Union Carbide in 1957, the pollution of the waterway increased further. By the end of the century factories and plants had been established along the length of both sides of the river from Rhodes to Parramatta. At Rhodes the appalling state of the water was equalled to that of the air. The area was an environmental calamity.

The transition from salubrious residential river to industrial drain was nowhere better symbolised than at Ryde where the classical, colonnaded house Subiaco had stood for 130 years. Built in 1837 for Hannibal Macarthur by the most fashionable of Georgian architects, John Verge, it was first named Vineyard because of its proximity to the early riverside vines; and renamed Subiaco when bought by the Catholic Church after the colonial economy underwent its first Depression. The estate was whittled away until the last parcel was sold to the hot water heater manufacturer Rheem in the early 1960s. Subiaco was then demolished along with everything else on the site to make way for factories, warehouses and car parks.

The post-industrial river

Since Europeans took the river from Aboriginal people and began to dramatically reshape its ecology, the natural cycles of climate and tide that had long influenced the waterway have been joined by other diverse social forces; economic, cultural, technological. The Clean Waters Act of 1970 was evidence of government taking seriously the issue of ecology where previously public instrumentalities had been complicit in the degradation of the river in the interest of wealth and job creation.

The 1988 bicentenary of European settlement showcased the harbour to the world and provided an impetus for the creation of Bicentennial Park on degraded river wetland near Homebush Bay. It also encouraged Sydney's bid for the 2000 Olympics. A centrepiece of that proposal was the remediation of polluted Homebush Bay. When the athletes left the land was given over to residential redevelopment.

By the end of the twentieth century, industry started vacating the riverside sites along the length of the waterway for a variety of other reasons. At Mortlake the impetus was technological; the last collier docked there in 1971. Natural gas took the place of coal gas and eventually the AGL plant was redundant altogether. Elsewhere leases expired and were not renewed. Ultimately the very function of the river as commercial highway became redundant.

The exodus of industry both reflected, and was hastened by, the rediscovered appreciation of waterfront amenity in Sydney Harbour; an economic and social shift that flowed gradually from the east to the west as the wharves, oil depots and boatyards closed. Vast areas taken up by industry have given way to equally large planned estates and parks. The salubrious residential river was rediscovered, recreated and reinvented.

The newly-created suburb of Breakfast Point now occupies the vast former AGL Mortlake site. An example of American-influenced New Urbanism, it is comprised of Bermuda-style apartments blocks such as 'Catalina' with its six storeys of 70 units. The 'village', as it is somewhat surprisingly called, has its own 'country club'.

Despite the environmental remediation that these new developments necessitate, the legacy of the industrialisation is long term. In 2006 commercial fishing licences for the harbour were terminated because of transfer of sediment contaminant to fish species. It is not clear if they will ever be reinstated. Recreational fishing west of the Sydney Harbour Bridge has been discouraged for the foreseeable future. [8] And while the intense residential redevelopment of the river's foreshores is based upon a new appreciation of the river, it will bring its own set of environmental challenges.

The Parramatta River Catchment Group, a collective of government and community organisations, was formed in 2008 in response to the legacy of historical use and issues associated with new development. One of its goals is to make the river swimmable again by 2025. The group's vision statement exemplifies the new understanding of a place that has undergone many changes: 'The Parramatta River is one of Australia's greatest and best known waterways. Its catchment is valued and celebrated by the community for its rich history, healthy natural environment and vibrant outdoor spaces'. [9]

Further reading

Attenbrow, Val. Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010.

Duff, Eamonn. 'Bennelong's grave found under a front yard in Sydney's suburbs.' Sydney Morning Herald, 20 March, 2011.

Blaxell, Gregory. The River: Sydney Cove to Parramatta. Ultimo, NSW: Halstead Press, 2009.

Clarke, Peter and Doug Benson. 'The Natural Vegetation of Homebush Bay – Two Hundred Years of Change.' Wetlands (Australia) 8, no 1 (1988): 3–15.

Hoskins, Ian. Sydney Harbour: A History. Sydney: New South, University of New South Wales Press, 2009.

Hoskins, Ian. Aboriginal North Sydney: An Outline of Indigenous History North Sydney. North Sydney, NSW: North Sydney Council, 2008.

McLoughlin, Lynnette C. 'Estuarine Wetlands Distribution along the Parramatta River, Sydney, 1788–1940: Implications for Planning and Conservation.' Cunninghamia 6, no 3 (2000): 579–610.

Vincent Smith, Keith. Wallumedegal: An Aboriginal History of Ryde. North Ryde, NSW: Community Services Unit, City of Ryde, 2005.

Stephensen, PR and Brian Kennedy. The History and Description of Sydney Harbour. Terrey Hills, NSW: Reed, 1980.

Taylor, Griffith. Sydneyside Scenery: And How it Came About. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1958.

Notes

[1] PR Stephensen and Brian Kennedy, The History and Description of Sydney Harbour (Terrey Hills, NSW: Reed, 1980), 183

[2] RJB Knight and Alan Frost (eds), The Journal of Daniel Paine, 1794–1797: Together with Documents Illustrating the Beginning of Government Boat Building and Timber Gathering in New South Wales, 1795–1805 (Sydney : Library of Australian History; Greenwich, England: Published in association with the National Maritime Museum, 1983), 38

[3] Lynnette C McLoughlin, 'Estuarine Wetlands Distribution along the Parramatta River, Sydney, 1788–1940: Implications for Planning and Conservation,' Cunninghamia 6, no 3 (2000): 603

[4] Keith Vincent Smith, Wallumedegal: An Aboritinal History of Ryde (City of Ryde, Ryde, 2005), 6

[5] Gregory Blaxell, The River: Sydney Cove to Parramatta (Ultimo, NSW: Halstead Press, 2009), 181. Much of the detail in this essay comes from this source. It is the most comprehensive account of the Parramatta River sites.

[6] Melanie Kembrey, 'One of Australia's first bridges found within Parramatta's historic Lennox Bridge', Sydney Morning Herald, 7 December 2014; 'Bridge Building in New South Wales, Pt 1. The Early Stone Bridges', Main Roads XVI, No 2 (December 1950): 37, 41

[7] 'A History of the Sydney Rowing Club,' Sydney Rowing Club website, http://sydneyrowingclub.com.au/Rowing/about-history.php, viewed 10 August 2015

[8] Sydney Harbour: A Systematic Review of the Science, 2014 (Mosman, Sydney: Sydney Institute of Marine Science), 45 available online at http://sims.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/SIMS-Harbour-Report_final_web-lowres1.pdf, viewed 10 August 2015

[9] 'About Us,' Parramatta River Catchment Group website, http://www.parramattariver.org.au/about, viewed 10 August 2015

.