The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Dyarubbin Project: Aboriginal history, culture and places on the Hawkesbury River

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Dyarubbin Project

[media]In 1829, the Reverend John McGarvie compiled a handwritten list of 178 Aboriginal place names along Dyarubbin, the Hawkesbury River. McGarvie, the Presbyterian incumbent at Ebenezer and Pitt Town at the time, headed his list ‘Native names of places on the Hawkesbury’, and wrote the names in ink and pencil on six pages in his notebook. They include the Aboriginal names for three of the Hawkesbury’s towns, including Windsor Bulyayorang, Richmond Marrangorra and Wilberforce Wangie, and also for the Blue Mountains Colomatta. McGarvie took a lot of care with this list, correcting spelling and adding pronunciation marks. The words appear in geographic order, so they also record where he and his Aboriginal informant/s travelled along the riverbanks. Perhaps most important of all, McGarvie often included locational clues, like settlers’ farms, creeks and lagoons.[1] These precious details meant that these long-lost names could be relocated on the ground, restored to their places, and that one day these beautiful, rolling words might even come back into common use.

Place names have enormous significance in Aboriginal society and culture. As in all societies, they signal the meanings people attach to places, they encode history and geography, they are wayfinding devices and common knowledge. In Aboriginal culture they are also crucial elements of shared understandings of Country, ‘integral to a group’s understanding of its history, culture, rights and responsibilities for land’.[2] Often place names are parts of larger naming systems – they name places on Dreaming tracks reaching across Country. Singular names can also embed the stories of important events and landmarks involving Ancestral Beings linguistically in the landscape.

Anthropologist and linguist Jim Wafer points out their use in songs, which were memory devices, or ‘audible maps’, travelling song cycles that narrate mythical journeys’.[3]

[media]Once every place on Dyarubbin and its tributaries had an Aboriginal name, clues to the way this Country was understood, used and experienced. Now only a handful survive on maps and in common usage.[4] But Reverend McGarvie’s list, now with his papers in the Mitchell Library, might change all that. In 2018, it inspired a collaborative project exploring Darug and Darkinjung history, culture and places on Dyarubbin.

Dyarubbin

Dyarubbin, the Hawkesbury River, flows through the heart of a vast arc of sandstone Country encircling Sydney and the shale-soil Cumberland Plain on the east coast of New South Wales. It rushes down from the Southern Highlands through deep gorges, meanders through the green terraces and floodplains, but then re-enters the ranges at Sackville to the north, twisting back and forth through a vast sandstone labyrinth until it reaches Broken Bay and flows into the Tasman Sea.[5]

[media]Dyarubbin has a deep human history, one of the longest known in Australia. Aboriginal people have lived here for around 50,000 years, their ancestors arriving millennia before the last Ice Age. Perhaps those people followed its winding course up from the coast, or walked down into the valley from the Blue Mountains to the west. Their history, culture and spirituality were inseparable from their river Country. Then, a mere two centuries ago, ex-convict settlers took land on the river and began growing patches of wheat and corn in the tall forests. Darug and Darkinjung men and women resisted the invasion fiercely and sometimes successfully, although ultimately overwhelmed by raids and massacres perpetrated by settlers and the military. Between 1794 and 1816, Dyarubbin was the site of one of the longest and most brutal frontier wars in Australian history.[6]

[media]Invasion and colonisation kicked off a slow and cumulative process of violence, theft of Aboriginal women and children, dispossession and the ongoing annexation of the river lands, and ultimately the erosion of Aboriginal culture and Language. Yet despite this sorry history, Darug and Darkinjung people managed to remain on their Country, and they still live on Dyarubbin today.[7]

The scores of names on McGarvie’s list contrast strikingly with the modern landscapes of the Hawkesbury and Western Sydney. With some important exceptions, Aboriginal people rarely see themselves represented in key heritage sites, or in the everyday reminders and triggers of public memory – like place-names. Yet Western Sydney is home to one of the biggest concentrations of Aboriginal people in Australia. Could McGarvie’s list also be a way to shift the shape of our landscapes towards a recognition of Aboriginal history and culture?

Decolonising colonial records and the Real Secret River: Dyarubbin project

There is an obvious and ironic problem here. How can we recover and reinstate Aboriginal stories and names by using the records of the colonisers, the same people who dispossessed and silenced Aboriginal people? The list was created by a coloniser: Reverend McGarvie, a scientifically minded man who had an interest in recording Language, perhaps because, like most other white people, he thought Darug and Darkinjung people would soon disappear. The words in ink and pencil, squiggles fixed on dry paper, were certainly alien to Aboriginal culture. Now they are silent, fossilised imprints of once-living, spoken language, locked away in a library, far from the Country they describe.

As Indigenous historians like John Maynard, Martin Nakata and Shino Konishi have shown, it is possible for Indigenous people to reclaim these sorts of records. They can be re-read from an Indigenous viewpoint, and, despite their limitations, they are precious to Indigenous people.[8] After all, these are not Reverend McGarvie’s words. They are the words of Dyarubbin’s Darug and Darkinjung people. McGarvie’s list was probably his own initiative, but nevertheless, this is a collaborative document, for Aboriginal voices spoke these words, spoke back to the coloniser. This list records moments of crossing-over, generosity, sharing and trust.

[media]There are other essential strategies for decolonising the practice of history. The most important of these is that research projects need to be collaborative, involving Aboriginal people themselves. Darug women Leanne Watson and Erin Wilkins, who had worked on other projects in Darug history and archaeology were enthusiastic about the possibilities of working together on McGarvie’s list. Jasmine Seymour and Rhiannon Wright also joined the research team, and collaboratively we designed the project, The Real Secret River: Dyarubbin.[9] Winning the State Library of New South Wales' generous Coral Thomas Fellowship for 2018–19, enabled us to begin the work of recovery, recognition and revitalisation of the river’s Darug and Darkinjung history, culture and Language based on McGarvie’s list.

Loss and Survival

[media]Throughout the nineteenth century, settlers constantly repeated the refrain that Aboriginal people were ‘dying out’ and would soon vanish entirely. The implication in popular fictional works that Aboriginal people on the river were ‘eliminated’ by a massacre perpetrated by settlers[10] is also untrue. Darug and Darkinjung people never ‘disappeared’ from Dyarubbin. They endured those terrible conflicts, they lived on the river when McGarvie was there in the late 1820s and they still live on the river today. Dyarubbin’s secret history is the long, deep and ongoing Aboriginal history of the river, so much of which was ignored, suppressed and forgotten by settlers, overlaid or drowned out by what historian Tom Griffiths calls ‘the white noise of history-making’.[11]

The project’s Darug researchers are committed to these quests. They want to recover and record Aboriginal Language and environmental and cultural knowledge, and raise awareness of Aboriginal presence and history in the wider community. Because the Aboriginal history of Dyarubbin is continuous, the project included an oral history component, recording twentieth century Aboriginal voices and stories of the river.

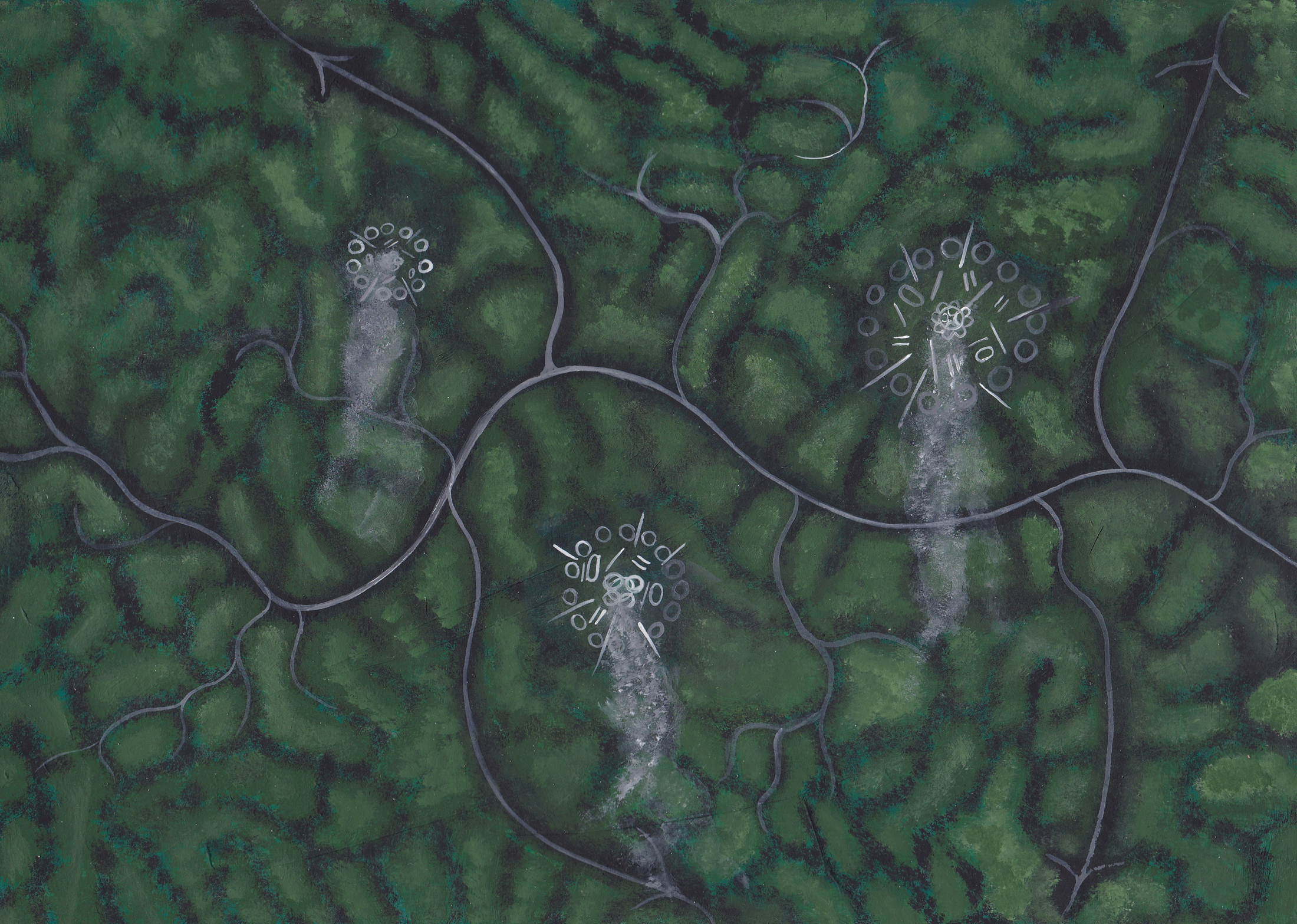

[media]The Dyarubbin project overall was framed and guided by an Aboriginal sense of Country: the belief that people, animals, Law and Country are inseparable, that the land is sentient, animate, inspirited, that it is an historical actor. Our program included an art project, commissioning Leanne Watson’s painting Waterholes. Inspired by the lagoons around Ebenezer and all the life and nourishment they offered people, Leanne’s painting speaks to this sense of Country. And, by untangling McGarvie’s list, we can even reinstate the Aboriginal names of some of those lagoons: Boollangay, Marramboollo, Darungara.

Digital mapping

[media]Digital mapping was the backbone of the project. Locating and mapping McGarvie’s names was the way to start recovering at least a part of what was a densely named Aboriginal landscape – one which is almost completely invisible on modern cadastral and street maps of this region. It’s true that all maps are political, and that they hide as much as they reveal. So multi-layered digital mapping can be a brilliant way to counter-map: it’s not only an essential tool for locating place-names, and visualising and understanding spatial patterns and relationships, it can tell the story of marginalised and dispossessed people, the people and places written out of mainstream history.[12]

The first step was to set up a simple online map which could be shared and used by whole team. The locations of the Aboriginal place names, settler names, archaeological sites, major natural features and post-contact sites of Aboriginal significance were stored as spatial data in ten different layers. This made it possible to see how the place-names might relate to geographical zones and features as well as archaeological sites.

[media]How did we relocate the Aboriginal place names? For 97 of the 178 listed names, Reverend McGarvie noted either a geographic feature, like a lagoon or creek, or a settler’s name, which indicates the location of a farm. Settlers bought, sold, leased and moved around a lot on the Hawkesbury in these years, so locating their farms could be tricky. But by checking and cross-referencing land, court, inquest and church records with maps, newspaper reports and local and family histories, we were able to locate these farms and map their Darug and Darkinyung place names.

[media]Locating natural features was not always straightforward either. Many are still extant today, although often in very different, sizes, shapes and conditions; others have long disappeared. So we used early maps to relocate the many lagoons that were drained and disappeared, or enlarged as dams; the creeks that were blocked up or changed course; and the now-vanished roads that McGarvie travelled with his Aboriginal informants. We mapped the lost river landscape.

McGarvie began his list with 16 place names simply headed ‘below Mr A Doyles’, that is, down the river from Andrew Doyle’s farm on Cambridge Reach. These names don’t have specific locations, so we can’t map them, but their meanings are intriguing, suggesting a river landscape of rugged rocky outcrops, a swimming place and social places like camps, corroboree grounds and contest grounds. It seems that McGarvie then realised that he needed to include locational details for the place names, and so he began recording them where he could. This is how we were able to relocate the names – and also work out the roads that McGarvie and his informants travelled to collect them. The mapped list shows that they made at least eight successive name-collecting expeditions:

Itinerary 1: Karkingang (Mauns Point) to Domba (Andrew Doyle's farm on Cambridge Reach) and back again, east side of Dyarubbin (9 place names)

Itinerary 2: Bilowa (Churchill’s farm at Sackville) to Engarabe (Ridge’s lagoon opposite Mauns Point), west side of Dyarubbin (24 place names)

Itinerary 3: Werrobarry (Larry Burns’ and Thomas Kirby’s farm at Sackville) to Wangie (Wilberforce) and back again, west side of Dyarubbin (35 place names)

Itinerary 4: Wėėndé (probably Old Pitt Town Road or Pitt Town-Dural/Pitt Town Roads to Tuggatugga (vicinity of David Robert’s farm on Cattai Creek, east side of Dyarubbin) (20 place names)

Itinerary 5: Gunanday, the Macdonald River (around St Albans) to Coorayong (north side of Webb’s Creek) (15 place names)

Itinerary 6: Dakal (Chaseling’s farm on Portland Reach) to Bardo Narang (Bardenarang Creek, Pitt Town), east side of Dyarubbin (37 place names)

Itinerary 7: Werriling (turn of the reach south of Bardenarang Creek) to Dal Cirric (South Creek or Wianamatta) east side of Dyarubbin (7 place names)

Interlude: a short list of names including Marrengorra (Richmond) Curry Jong (Kurrajong), and Colomatta (the Blue Mountains) (4 place names)

Itinerary 8: Bandi Bandi (Joseph Smith’s farm on Gunanday) to Malu (Marlow Creek, Higher Macdonald) (8 place names)

It is clear from the map that McGarvie tried to be meticulous and thorough, covering first one side of Dyarubbin, then the other. But there are long stretches which he didn’t visit – for example, the river reaches between the Colo River and Wisemans Ferry. They were the more inaccessible areas where there were few settlers and probably no roads. These areas are very rugged and isolated even today – perhaps this explains why the first 16 place names don’t have any locational details.

We think that McGarvie was probably asking for the names of places familiar to him – for example, farms occupied by people he knew, and obvious landmarks, like large lagoons or prominent mountains. But for well over a third of the names, he either did not note a specific location, or he gave a general one, like ‘North side of the river’ or ‘below Mr A. Doyles’. The names which don’t have locations may have been in areas where there were no settlers or obvious landmarks, at least to McGarvie. But these unlocated names may be especially significant: Aboriginal informants may have given them to McGarvie because these were places that were important to them.

Seeing the river whole

But the project is about more than relocating names on a map, important as this is. As you will see in the other essays in this story cycle, it is about putting the places, names, geographies and stories of the river back together. We see McGarvie’s list as a portal, an invitation to recover what historian Greg Dening called the past’s own present, the river as Aboriginal people experienced it in their own times.[13] To do this, and to understand the place names on McGarvie’s list as fully as possible, we needed to see the river whole. Besides working with Traditional Owners to reconnect the list of place-names to Darug and Darkinyung knowledge of Country and culture, we needed expertise in a range of disciplines, people with special skills.

Our team expanded to include archaeologist and historian Paul Irish, linguist and anthropologist Jim Wafer, geologist, writer and bushwalker Gil Jones and photographer Joy Lai. Many other locals and experts generously supported the project too, including Hawkesbury historians Michelle Nichols and Jan Barkley-Jack, museum curator Rebecca Turnbull, bushwalker Rene Breuls, Aboriginal Languages scholar Jeremy Steele, and Dennis Mitchell and Michael Kemp, who were born and bred on the Hawkesbury and know it intimately.

For this project we needed to research across a number of disciplines:

[media]History, from the invasion and colonisation of Dyarubbin to the intricate ever-shifting pattern of river farms, camps, roads and landmarks; and Aboriginal history, from deep time to the post-invasion story of how they defended this Country and managed to survive over the next two centuries.[14]

[media]Archaeology, because we needed to look beyond settler records, and beyond Western ways of thinking. In the Aboriginal world all things and events have supernatural reason and purpose, cause and effect – every major or distinctive landscape feature will have a supernatural explanation, a Dreaming story.[15] The deep spiritual dimension of this Country is recorded in traditional knowledge and in the art and material culture created by Aboriginal people themselves – the archaeological record. Hundreds of sites are still extant along Dyarubbin, in Colomatta (the Blue Mountains), and in the ranges to the north and northeast.[16]

[media]Linguistics was essential for analysing the words on McGarvie’s list. We compared each word on McGarvie’s list to available dictionaries of seven different Aboriginal Languages spoken on Dyarubbin and in the wider region, including Darug/Sydney Language, Darkinyung, Karee, Gundungurra, Hunter River/Lake Macquarie, Gathang and Wiradjuri.[17] We also checked Pidgin, the cross-cultural language that emerged after 1788, and two lists of Aboriginal names for trees and plants, one compiled at Broken Bay by Robert Brown in 1804, and the other by William Macarthur in the 1850s.[18] Why so many dictionaries? Two reasons: first, every dictionary is fragmentary – it only records part of each Language. And second, adjoining Aboriginal Languages often shared around 70% of their words. These are called cognate words. So, if the source word is not in one dictionary, it may well appear in another. Some words occur across two or three languages.

[media]Geography, geology and ecology tell us about the river’s natural history, formation and characteristics, which were fundamental to Darug and Darkinjung life on Dyarubbin; understanding them helps contextualise many of the place-names and their glosses on McGarvie’s list. Sometimes the words in turn helped to recover something of the lost landscapes of the 1820s.[19]

[media]And finally, we needed to put on our boots and get out on Country, following in the footsteps of McGarvie and his Darug and Darkinjung friends, to see and record the way all of this comes together. We completed five field trips, each one in a different area on the river or in the wider region, and each one raising significant issues about Country, Language, history and the future. This was, and continues to be, the most rewarding, illuminating and inspiring part of the whole project, the time when it all comes together. For Aboriginal people especially, visiting Country is a spiritual experience: they sense past and present converging, and the presence of their Ancestors.

McGarvie’s list and Aboriginal Dyarubbin

[media]What can the words on McGarvie’s list tell us about the Aboriginal world of Dyarubbin? In any project like this, it is essential to keep in mind the sheer complexity of both Language and cross-cultural communication. These place names, for example, could refer to the landscape and environment of Dyarubbin, or they may have been metaphors. Some appear to archaisms – old words which fell out of general use and were only preserved as place name (this often happens with English place names too); or they may be fragments of Dreaming stories or songlines.

As discussed in our companion essay McGarvie’s list and Aboriginal Dyarubbin, reading the names and their possible meanings in their wider contexts (geography, ecology, archaeology and history) has been essential to both relocating them and working out what they most likely mean. Nevertheless, some meanings remain tentative, mysterious and ambiguous, while other place names have more than one possible meaning. Why? Because most of the Dreaming stories and knowledge about Country of which they were a part have been lost in the wake of colonisation, the marginalisation of Darug and Darkinjung people and the suppression of their Languages and cultures.

McGarvie’s place names are rich and precious, but they are only fragments, small, intriguing glimpses of an immensely complex culture and landscape. So we see this project as a beginning, rather than a definitive end. We hope that new knowledge in Languages and linguistics will allow future researchers to refine these glosses and recover more of the treasures held in McGarvie’s list. Rediscovering Dyarubbin is an ongoing project.

To read about what the McGarvie list has revealed about Darug and Darkinyung history, culture and places on Dyarubbin, please go to the essay McGarvie’s List and Aboriginal Dyarubbin.

Notes

[1] Reverend John McGarvie, Papers, 1825-1847, including ‘Native Names of Places on the Hawkesbury’, A1613, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

[2]Luise Hercuse, Flavia Hodges and Jane Simpson (eds), The Land is a Map, ANU Epress, Canberra, 2002, p 2.

[3]James Wafer, ‘Ghost-writing for Wulatji: incubation and re-dreaming as song revitalisation practices’, in James Wafer and Myfany Turpin (eds), Recirculating songs: revitalising the singing practices of Indigenous Australia, Hunter Press, Newcastle, 2017,208.

[4] For example, Colo, Kurrajong, Bardo Narrang, Wheeny, Yarramundi, Melong, Berowra, Cowan.

[5]Grace Karskens, People of the River: Lost Worlds of Early Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2020, pp 3-4, 17-21.

[6] Grace Karskens, People of the River: Lost Worlds of Early Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2020, pp 21-69, 123-175.

[7] Grace Karskens, People of the River: Lost Worlds of Early Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2020, chapters 9, 11, 13 and 15. See also James Kohen, The Darug and their neighbours: The traditional Aboriginal owners of the Sydney region, Darug Link and Blacktown and District Historical Society, Sydney, 1993; Jack Brook, Shut out from the World: The Hawkesbury Aborigines Reserve and Mission 1889-1946, NSW, Deerubbin Press, Berowra Heights, 1999.

[8] See, for example, John Maynard, ‘Awabakal voices: the life and work of Percy Haslem’, Aboriginal History, vol. 37, 2013, 77-92; Martin Nakata, Disciplining the Savages, Savaging the Disciplines, Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press, 2007; Shino Konishi, ‘First Nation scholars, settler colonial studies and Indigenous history’, Australian Historical Studies, vol. 50, no. 3, 2019, 285-304, and see Konishi’s numerous other publications.

[9] Darkinjung woman Cindy Laws also joined the project team.

[10] For example, Kate Grenville, The Secret River, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2005.

[11] Tom Griffiths, Hunters and Collectors: The Antiquarian Imagination in Australia, Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp 4, 5, 167.[

[12] See Craig Dalton and Tim Stallman ‘Counter-mapping Data Science’, The Canadian Geographer/Le Geographe Canadien, vol. 62 no 1, 2018, 93–101 DOI: 10.1111/cag.12398.

[13] Greg Dening, Reading/Writing, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1998, p 48.

[14] Key resources include Jan Barkley-Jack, Hawkesbury Settlement Revealed: A New Look at Australia’s Third Mainland Settlement 1793-1802, Sydney, Rosenberg Publishing, 2009; Grace Karskens, People of the River: Lost Worlds of Early Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2020; R J Ryan (ed.), Land Grants 1788-1809, Australian Documents Library, Sydney, 1981; the many available local and family histories; and National Library of Australia, Trove Newspapers and Gazettes.

[15] Grace Karskens, People of the River: Lost Worlds of Early Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2020, chapter 15.

[16] New South Wales Department of Environment and Heritage, Aboriginal Heritage Information Management System [database] http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/licences/AboriginalHeritageInformationManagementSystem.htm ; I. M. Sim, Rock Engravings of the Macdonald River District, NSW, Occasional Papers in Aboriginal Studies No. 7, Prehistory and Material Culture Series No. 1, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1966; Kelvin Knox and Eugene Stockton (eds), Aboriginal Heritage of the Blue Mountains: Recent Research and Reflection, Blue Mountain Education and Research Trust, Lawson, NSW, 2019; Gil Jones, Bulga, Bala, Boree, Bulga Books, St Albans, NSW, 2017; Gil Jones, Powers of Nature: Spirits of flood and fire across Sydney’s sandstone country, Bulga Books, St Albans, NSW, 2018.

[17] Jakelin Troy, The Sydney Language, Australian Dictionaries Project and Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra, 1993; Caroline Jones, Darkinyung Grammar and Dictionary: Revitalising A Language From Historical Sources, Muurrbay, Nambucca Heads, NSW, 2008; Reverend Lancelot Edward Threlkeld, ‘Specimens of the Language of the Aborigines of New South Wales to the Northward of Sydney – Karree’, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (MSS A382, pp. 130-40); Jim Barrett, Gandanguurra: The Language of the Mountains People – and beyond, Neville Bush Pty Ltd, Glenbrook, NSW, 2015; Amanda Lissarrague, A Salvage grammar and wordlist of the language from the Hunter River and Lake Macquarie, 3 vols, Muurrbay, Nambucca Heads, NSW, 2006; Amanda Lissarrague, Grammar and Dictionary of Gathang: The Language of the Birrbay, Giringay and Warr, Muurrbay, Nambucca Heads, NSW, 2010.

[18] Robert Brown ‘Native Names of Plants taken down from Bagara’, Field notes MS B3V ff87v-91r, 1804, Botanical Library, Natural History Museum London, see Australian Joint Copying Project, Reel 2495, vol. 2 pp 119-22, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales; William Macarthur and others, ‘Woods of the Southern Districts’ in Catalogue of the natural and industrial products of New South Wales forwarded to the Paris Universal Exhibition of 1867, Sydney, 1861, pp 62-70.

[19] Some key references include Doug Benson and Jocelyn Howell, Taken for Granted: The Bushland of Sydney and its Suburbs, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 1990; Sue Rosen, Losing Ground: An Environmental History of the Hawkesbury-Nepean Catchment, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1995; H. F. Recher, P. A. Hutchings, and S. Rosen, ‘The biota of the Hawkesbury-Nepean catchment: reconstruction and restoration’, Australian Zoologist, vol. 29, nos. 1-2, August 1993, 3-41; Paul Boon, The Hawkesbury River: A Social and Natural History, CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, 2017.