The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Bridge Street Affray

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

[media]Police in Sydney and across New South Wales were authorised to carry firearms in early 1894 as a result of the Bridge Street Affray, in which several police officers were brutally attacked and injured. Members of the New South Wales Police Force have carried firearms ever since.[1]

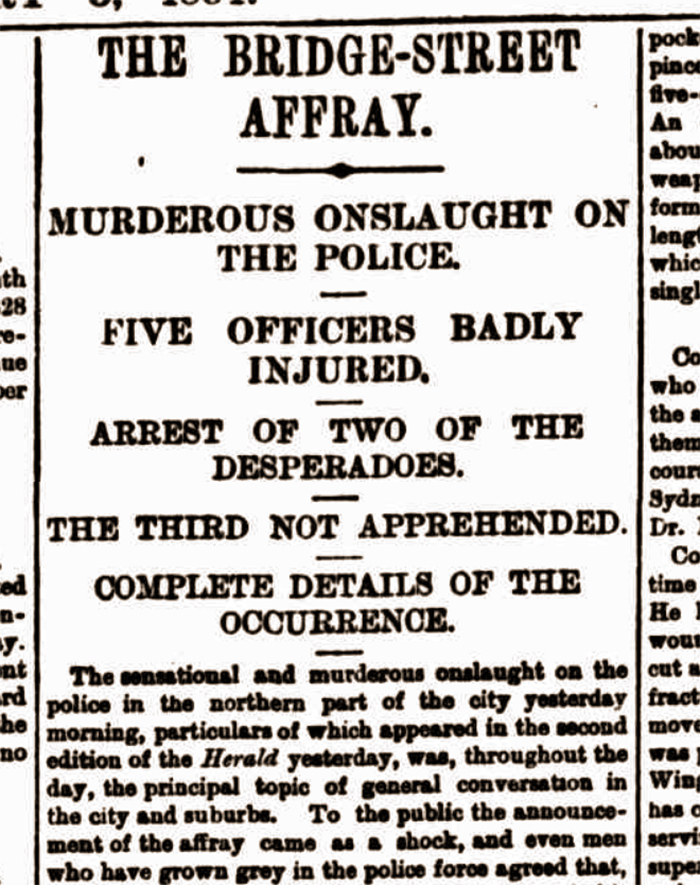

The Affray

The event that became known as the Bridge Street Affray began in the very early hours of the morning of Friday, 2 February 1894 when three men — Charles Montgomery, Thomas Williams and a third, never definitively identified, man — attempted to break into the safe in the Bridge Street offices of the Union Steamship Company.[2]

The building's night watchman had noticed something amiss while on his rounds and was consulting with a policeman on his beat when the robbers abandoned the attempt and left the building. Walking down Bridge Street towards Phillip Street, they were confronted by several law enforcement officers: Senior Constable Ball, Senior Constable McCourt and Constable Lyons. The robbers drew weapons. First, heavy iron jemmies (short crow bars) of about 2 feet (approximately 60 cm) in length were used to assault the constables. Both McCourt and Lyons were bashed in the head and left unconscious. Ball was quicker on his feet and evaded a blow to the head but one of the robbers had a second type of weapon: he drew a revolver and threatened to shoot. This threat was not carried out and the robbers turned and ran up Bent Street where they separated. One man went towards The Domain while Montgomery and Williams, only recent arrivals in Sydney from Melbourne, ran down Phillip Street and, unknowingly, towards the Water Police Station and Court.[3]

[media]Ball continued to shout for reinforcements that duly emerged from the very buildings the two men were now running towards. The struggle to subdue Montgomery and Williams was fierce. The second man, Williams, proved comparatively easy to overcome. In contrast the first man, Montgomery, refused to give up the fight even when dragged into the Police Station. The Sydney Morning Herald reported enthusiastically that the Water Police Station 'was the scene of much excitement' [4] and The Daily Telegraph noted that the case had sent 'a thrill through the community'.[5]

With two of the three burglars finally incarcerated, it was revealed that four members of the constabulary required urgent medical treatment, three for head injuries (including Constable Bowden for a fractured skull) and one for a broken arm. The men were taken by cab to Sydney Hospital[6] on nearby Macquarie Street. Another officer, Constable Alford, was taken to the hospital the next day when the extent of the internal injuries he had suffered during the affray became apparent.[7]

The Trial

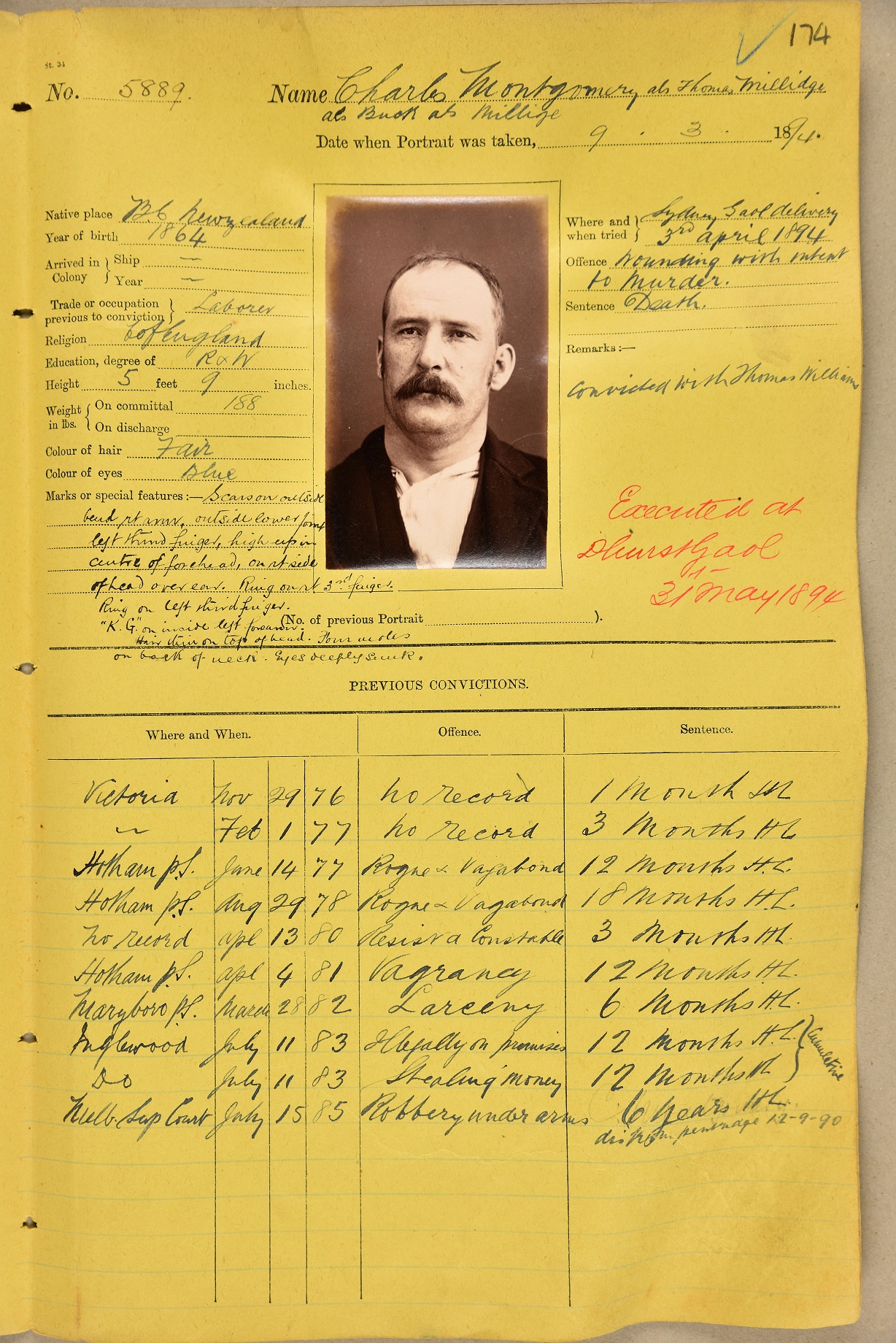

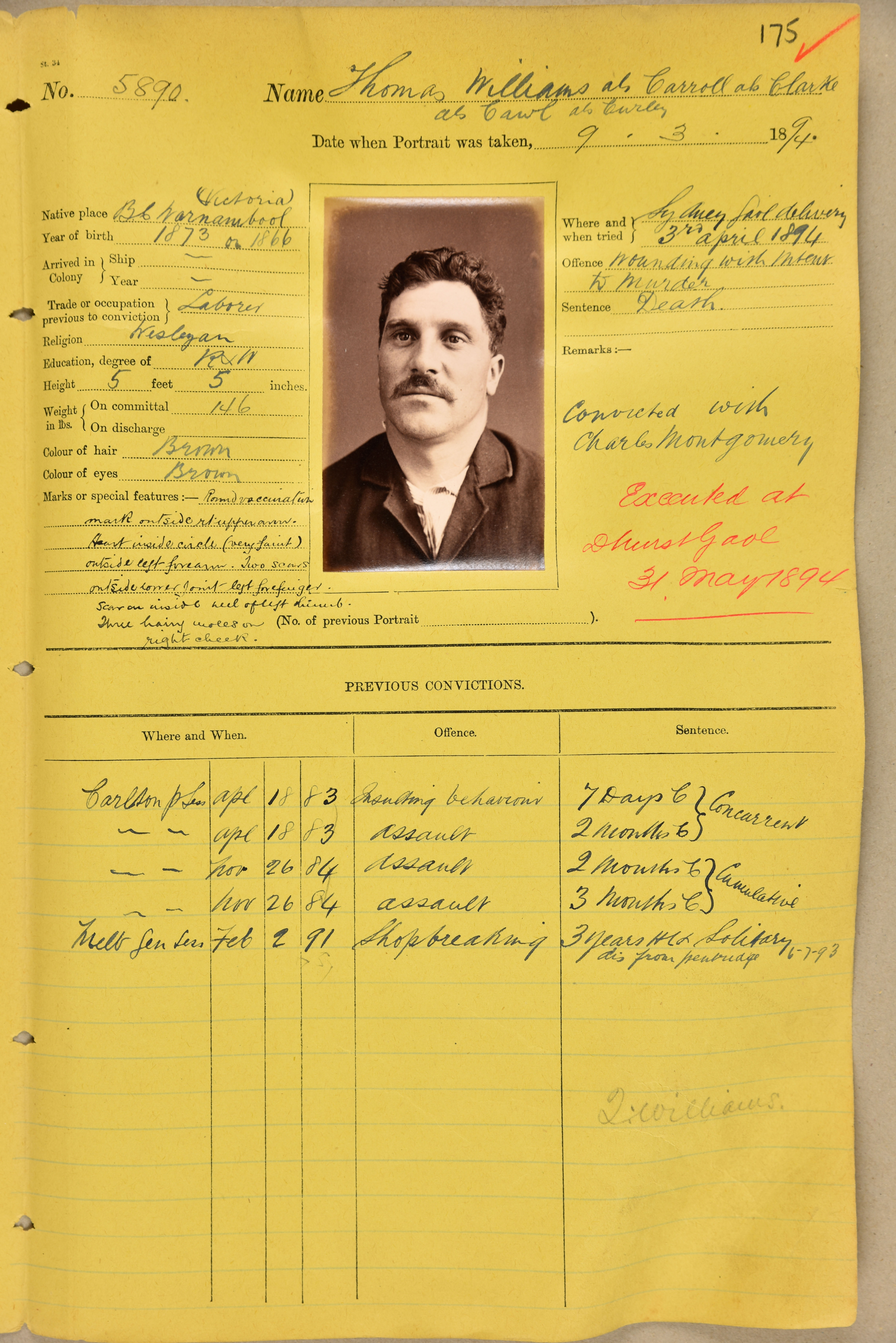

[media]The inside of a court room was not an unfamiliar sight to either Montgomery (aged 30) or Williams (aged 21). The two men, each having operated under various aliases, were career criminals identified as professional burglars and who had served sentences in Pentridge Gaol in Melbourne, Victoria. Montgomery, the older and more hardened of the two men, had served a six-year sentence for a bank robbery and was well known for resorting to violence. Williams had served a three-year sentence for shop breaking.[8]

Montgomery and Williams were charged with breaking into the premises of the Union Steamship Company and appeared in the Water Police Court on 2 February 1894.[9] In addition, Montgomery was charged with maliciously wounding Senior Constable McCourt and Constable Lyons with intent to murder, and Williams was charged with maliciously wounding Constables Taylor and Alford with similar intent. There were delays in the hearing of evidence as key witnesses remained in Sydney Hospital.[10] When the witnesses were heard, the testimonies resulted in both men being committed to stand trial at the Central Criminal Court at Darlinghurst.

Montgomery and Williams faced Justice Stephen in the Central Criminal Court on Tuesday, 3 April 1894.[11] In a reflection of the short trials that were typical in the colonial era, the jury of twelve retired at 7.10 pm and returned at 8 pm with verdicts of guilty against both of the prisoners. Justice Stephen declared Montgomery and Williams to be 'desperate characters' and issued the ultimate penalty, that they 'be taken thence to the place of execution, at such time as the Governor shall appoint, and be hanged by the neck until your bodies are dead'.[12]

The Punishment

[media]It was acknowledged shortly after the Bridge Street Affray that the men would have difficulty in securing a fair trial. Their previous crimes, and the crimes committed in Sydney, were judged by the press in widely circulating newspapers well before they had a chance of being judged by their peers within the confines of a courtroom.[13]

Alongside public demands for punishment, there were also popular appeals for clemency. Public meetings in the Sydney Town Hall and the Domain were held [14] and by 30 May 1894, the day before the condemned men were sentenced to hang, more than 25,000 men and women had signed a petition asking for mercy. Signatories included parliamentarian George Black, Cardinal Patrick Moran and social reformer Rose Scott. Highlighting the harshness of the penalty, the petition was also signed by six members of the jury that had delivered the guilty verdicts and Constables Bowden and Alford, two of the men seriously injured in the affray.[15]

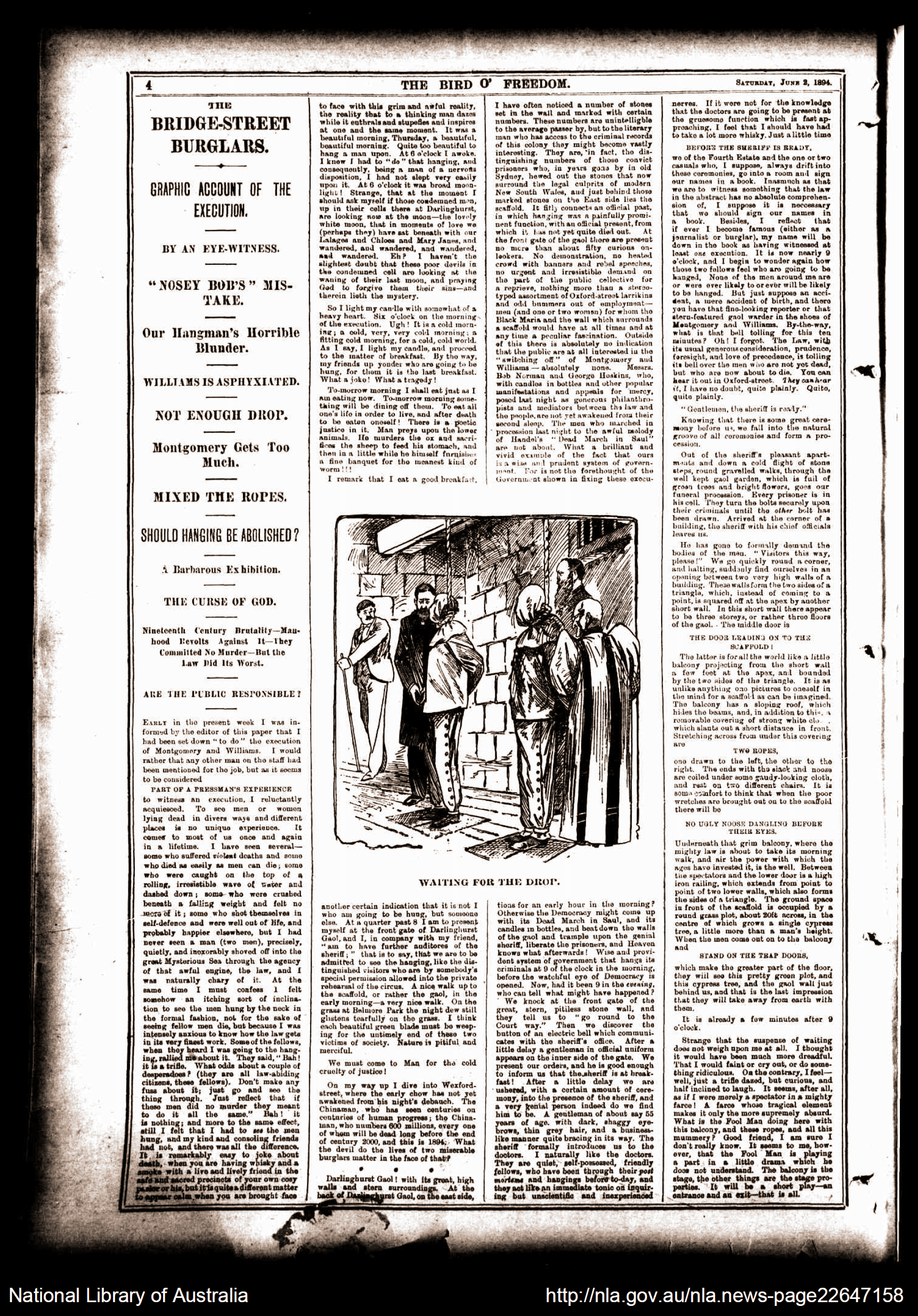

The pleas for reprieves were denied however and both men faced the gallows at Darlinghurst on Thursday 31 May 1894.

[media]In a terrible turn of events, the men did not stand in front of their allocated ropes. The Chief Public Executioner, Robert 'Nosey Bob' Howard, had set a short rope had been set for Montgomery, the larger of the two men, and a long rope for Williams. When Montgomery fell his death was instantaneous. Williams, in contrast, fainted and became entangled in the rope and the assistant hangman was forced to shake the rope in an effort to allow the body to hang in the upright position. Williams eventually died from suffocation.[16]

The Impact

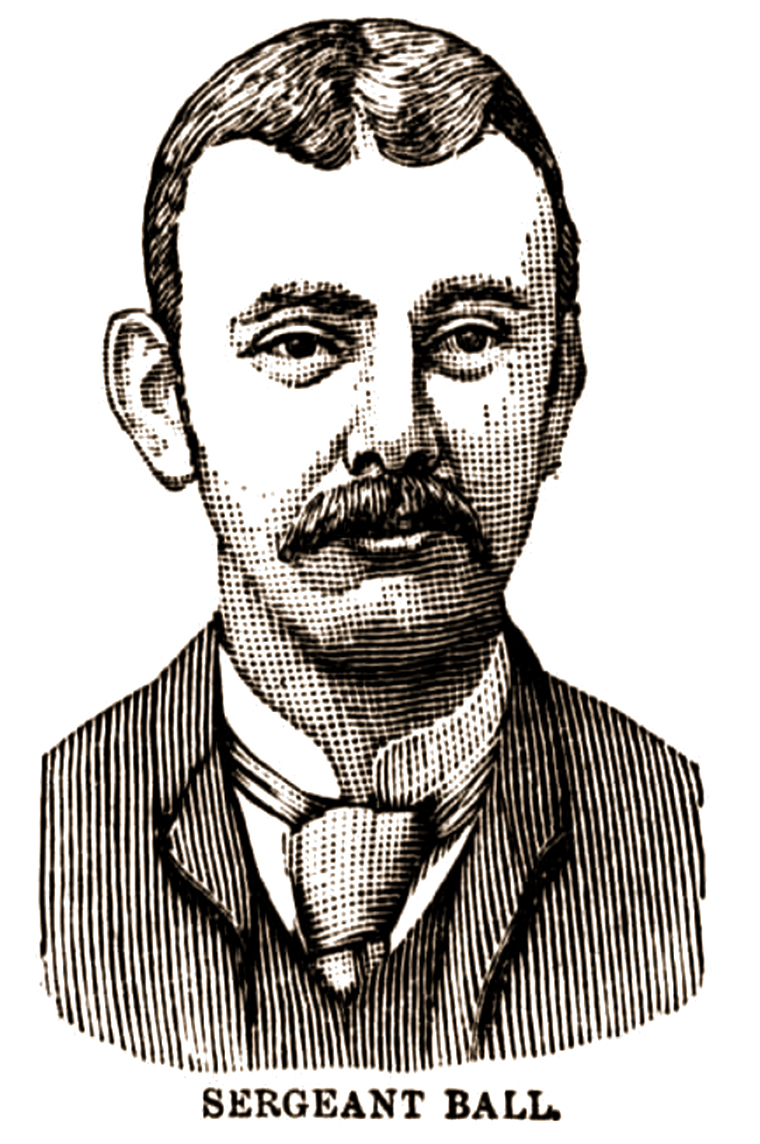

The police officers involved in the Bridge Street Affray were all noted for their bravery. Senior Constable Ball was promoted to Sergeant.[17]

The incident changed policing in Sydney and across the state. Within days, constables on night duty were 'being supplied with revolvers and cartridges'.[18] The brutal wounding of five police officers inspired the popular press of the day to demand that all constables be issued with revolvers as standard practice and the Premier of New South Wales, Sir George Dibbs (who was facing an election later in the year) quickly agreed to the arming of police officers. [19] This policy remains in place in 2018.

Notes

[1] History 1889-1987, New South Wales Police website n.d. http://www.police.nsw.gov.au/about_us/history viewed 26 May 2018; In 1915, Lillian Armfield was one of the first (of only two) women to be appointed as a police officer in Australia. In recognition of the dangerous work Armfield was undertaking, she was carrying a revolver when female officers in New South Wales “were not officially given guns until the 1970s”. Leigh Straw (2018). Lillian Armfield: How Australia’s first female detective took on Tilly Devine and the Razor Gangs and changed the face of the force (Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2018), xiv, 182

[2] Murderous Affray with Burglars, The Sydney Morning Herald 2 February 1894, p5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13939603 viewed 27 May 2018

[3] Mark Hearn, Hard Cash: John Dwyer and his contemporaries, 1890-1914. PhD Thesis. (University of Sydney, 2000), pp166-167

[4] Murderous Affray with Burglars, The Sydney Morning Herald 2 February 1894, p5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13939603 viewed 27 May 2018

[5] Murderous Encounter with Burglars, The Daily Telegraph 3 February 1894 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/236099757 viewed 27 May 2018

[6] Mark Hearn, Hard Cash: John Dwyer and his contemporaries, 1890-1914, PhD Thesis. (University of Sydney, 2000), p167

[7] The Bridge Street Affray, The Sydney Morning Herald 5 February 1894, p5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/28258001, viewed 27 May 2018

[8] Mark Hearn, Hard Cash: John Dwyer and his contemporaries, 1890-1914, PhD Thesis. (University of Sydney, 2000), pp167-168

[9] In The Water Police Court, The Daily Telegraph, 3 February 1894, p5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/236099789 viewed 27 May 2018

[10] The Affray With Burglars, Evening News 9 February 1894, p4 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/114075096 viewed 27 May 2018

[11] Mark Hearn, Hard Cash: John Dwyer and his contemporaries, 1890-1914, PhD Thesis. (University of Sydney, 2000), p168

[12] The Bridge Street Affray, Evening News 4 April 1894, p4 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/114081413 viewed 27 May 2018

[15] The Condemned Bridge-Street Burglars, The Daily Telegraph, 22 May 1894, p6 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article236146566 viewed 30 May 2018; The Condemned Men Mongomerty and Williams, National Advocate (Bathurst), 26 May 1894, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156619106 viewed 30 May 2018; Evening News, 12 May 1923, p6 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article118845213 viewed 30 May 2018; Mark Hearn, Hard Cash: John Dwyer and his contemporaries, 1890-1914, PhD Thesis. (University of Sydney, 2000), pp169-170

[13] The Affray with Burglars, Evening News 9 February 1894, p4 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/114075096 viewed 28 May 2018

[14] A Reprieve Urgently Requested, Meeting in the Town Hall, The Sydney Morning Herald 26 May 1894, p12 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13952907 viewed 27 May 2018; Meeting in the Domain, The Sydney Morning Herald 28 May 1894, p5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13953190 viewed 27 May 2018

[16] Execution of Montgomery and Williams, The Sydney Morning Herald 1 June 1894, p5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/13953641 viewed 27 May 2018

[17] The Bridge Street Affray, The Sydney Morning Herald 5 February 1894, p5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/28258001 viewed 27 May 2018

[18] The Bridge Street Affray, The Sydney Morning Herald 5 February 1894, p5 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/28258001 viewed 27 May 2018

[19] Mark Hearn, Hard Cash: John Dwyer and his contemporaries, 1890-1914, PhD Thesis. (University of Sydney, 2000), p164