The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Thomas Fisher

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Thomas Fisher

A bootmaker and the son of convicts, Thomas Fisher became a significant benefactor of the library of the University of Sydney, which was named Fisher Library in his honour.

Birth and childhood

Thomas Fisher's father John arrived on the Perseus in 1802 at the age of 47, with a life sentence for sheep stealing. As an experienced shepherd he was assigned to Reverend Rowland Hassall's farm near Castle Hill. Hassall bred horses and Fisher became an expert horseman and jockey. Thomas' mother, Jemima Bolton, aged 34, arrived on the Canada in 1810, sentenced to seven years' transportation for stealing clothing. She was assigned as a government housekeeper at Parramatta. John and Jemima met and were married by Reverend Samuel Marsden at St John's Church, Parramatta in 1811. [1]

John Fisher's skills as a horseman and jockey had brought him in contact with many of the leaders of Sydney society, including the Lieutenant-Governor Colonel Maurice O'Connell. Fisher often rode his horses to victory at meetings of the Sydney Racing Club and when O'Connell was recalled to England it seems likely that he recommended Fisher for a free pardon. In 1814 John Fisher was granted a pardon and 50 acres of land at Appin. Farming was difficult and after battling droughts, floods and attacks by Aborigines, the Fishers admitted defeat in 1818 and moved to Sydney to a house on Brickfield Hill.

By this time there were three daughters – Jemima, Mary Ann and Sarah. On 23 January 1820 a son was born whom they named Thomas. John Fisher died in 1832. His will stipulated the income from renting rooms in the family house at the corner of Clarence and Market Streets was to go to his widow for the 'support of herself and the maintenance and education of my son Thomas Fisher until he shall attain the age of twenty-one years or day of marriage'. [2]

Bootmaker, retailer and investor

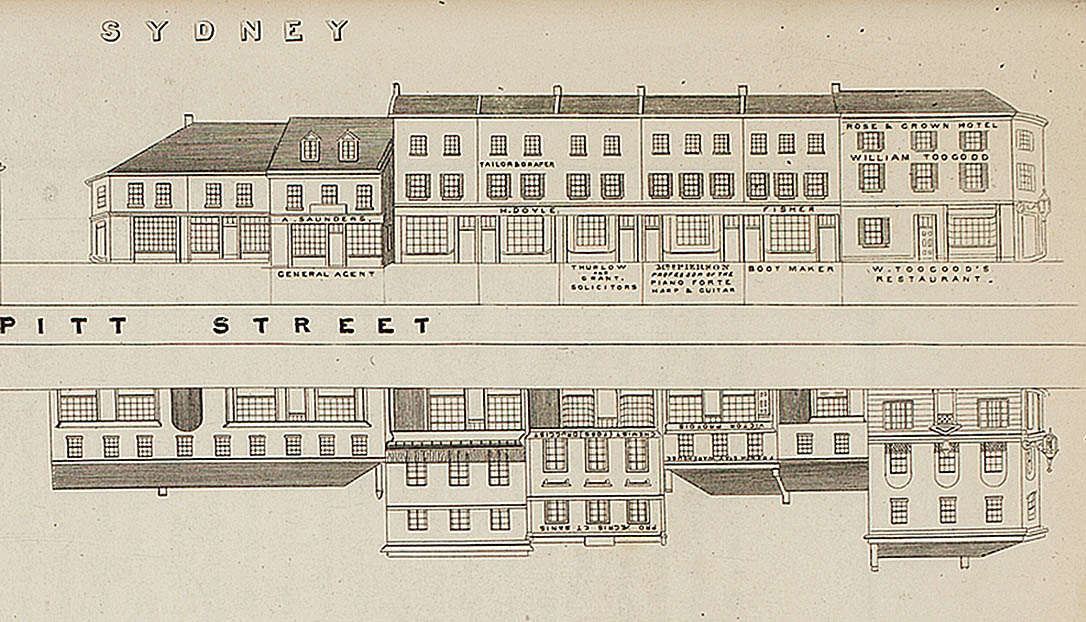

[media]Six months later Jemima died, leaving the four Fisher children orphans. Thomas, aged 12, was apprenticed to a bootmaker, probably to James White who was one of his father's executors. In 1841 when Thomas turned 21, the Clarence Street property was sold and the proceeds divided among the four children. In 1842 Thomas opened a boot and shoe shop on the east side of Pitt Street, one door north of King Street. [3] It was a three-storey building with the shop at ground level, rooms on the first floor that were rented out, and a residence on the second floor occupied by Fisher and his sister Sarah. Because of its proximity to the law courts, the first floor tenants were lawyers, many of whom, it can be assumed, became Fisher's friends during the 30 years he owned the building.

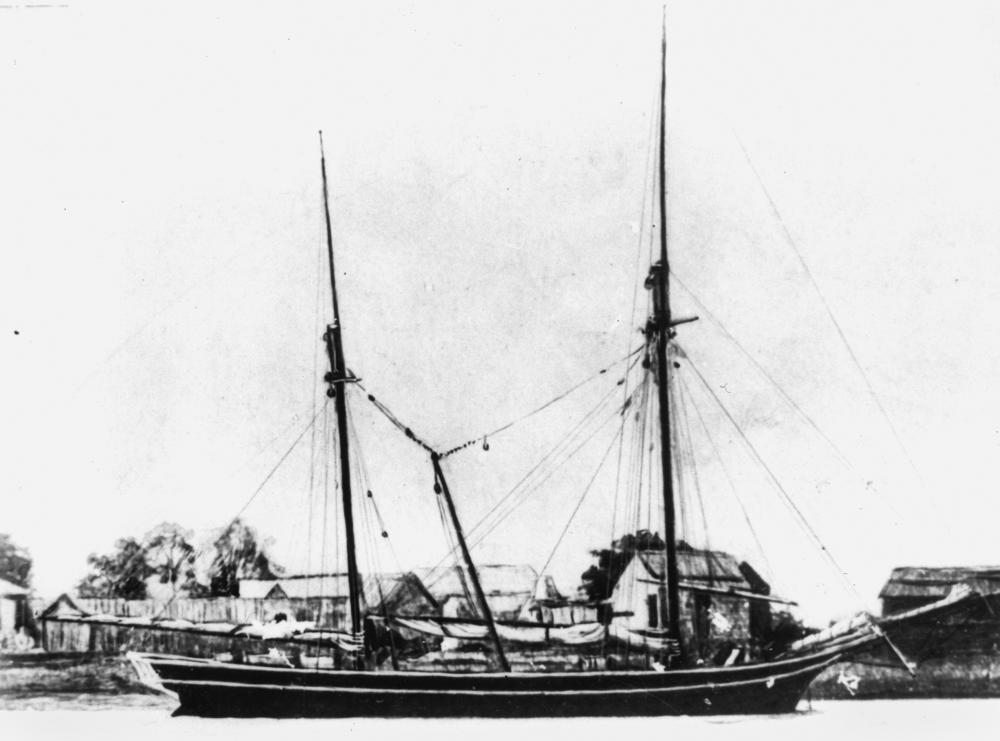

Fisher's [media]business prospered and his shop became a boot and shoe warehouse from which he sold both custom-made footwear and imported stock from England. In time he was able to consider investing some of his surplus capital. He began lending money on the security of mortgages and also began gradually to acquire small parcels of property, which he leased to tenants. By the time of his death he held more than 50 mortgages and received rent from more than 20 tenants in various properties around the inner suburbs of Sydney. He also owned a two-masted schooner, the Tom Fisher, which carried cargo along the eastern coast of Australia and to nearby islands.

Retirement

Sarah, who had acted as his housekeeper, died in 1871 and was buried in Camperdown Cemetery in the family vault. Although Fisher was only in his early fifties he suffered from Bright's disease, a chronic kidney complaint, and decided to retire and concentrate on his investments. At the end of 1872, after 30 years of successful and profitable trading, he closed the business of 'T Fisher, Ladies' and Gentlemen's Boot and Shoe Manufacturer' [4], sold the King Street building, and retired to a substantial two-storey house on the corner of Alma and Codrington Streets (now Maze Crescent and Butlin Avenue, respectively) in the suburb of Darlington. He named the house 'Clarence House', perhaps as a link with his childhood home in Clarence Street. Attached on the Alma Street side was a single storey cottage rented to James Beattie, the captain of the Tom Fisher. Beattie's daughter Ellen became Fisher's housekeeper for the remaining decade of his life.

University of Sydney bequest

Fisher was a member of the congregation of St James' Church in King Street where the rector was Canon Robert Allwood, a Fellow of the University Senate and vice-chancellor from 1869 to 1883. Clarence House was only one block from Victoria Park and the University of Sydney, across busy Newtown (City) Road, and Fisher frequently walked in the university grounds. At this time the university had fewer than 100 students and only a handful of staff. Fisher regularly attended the annual ceremony of commemoration of benefactors held in the University's Great Hall, where former benefactors were named and significant new gifts or endowments announced. Thus Fisher would have heard in 1879 that businessman Thomas Walker had purchased and presented to the university the important private collection of Nicol Stenhouse, one of Fisher’s fellow members of the Sydney Mechanics School of Arts. In announcing this gift, Chancellor Sir William Manning noted that the Stenhouse books had increased the university library's holdings by 50 per cent and had precipitated a crisis in accommodation. He told his audience

I will be so bold as to give expression to the hope that the day will come when one of our men of great wealth and equal public spirit will ... earn the gratitude of their country by erecting for the University a library worthy of comparison with like edifices at Home. [5]

A year later Fisher made his will, leaving almost all of his estate to the university, to be used

in establishing and maintaining a library ... for which purpose they may erect a building and may purchase books and do anything which may be thought desirable for effectuating the objects aforesaid. [6]

He left no record of his reasons but it seems reasonable to assume that Manning's appeal had been influential.

Death

Fisher's illness took its inevitable toll and he died of kidney failure in Sydney Hospital on 27 December 1884, just one month short of his sixty-fifth birthday. His will directed that he be interred in the family tomb in Camperdown Cemetery where two of his sisters already lay. For reasons unknown, this direction was not complied with. It could be that his nephews, who apparently arranged the funeral, were unaware of this instruction – they were also unaware that all but one of them were excluded from the list of beneficiaries of Fisher's estate. He was buried in Waverley Cemetery and a monument was later erected over the grave, inscribed:

Sacred to the memory of Thomas Fisher Esq. late of Alma Street, Darlington, South Sydney, who died 27 December 1884, aged 64 years. His munificent bequests are recorded in the annals of the Sydney University, School of Arts, and other charitable institutions. [7]

The will

Probate was granted in April 1885 and the value of the estate exceeded £50,000. Ellen Beattie, Fisher's housekeeper, was left Clarence House, the cottage next door where her father was the tenant, all the household furniture, and £100. The house was eventually acquired by the university and was demolished about 1970 to make way for a science laboratory. The demolition failed to substantiate the theory held by one branch of the family that 'thousands of pounds in gold and silver coins' were hidden in the house. [8]

Seven charitable institutions were named to share £1,000. The income from £200 was to be used to maintain his tomb in good condition and to erect a memorial tablet in St James' Church. The fund to maintain the family tomb at Camperdown was diverted to erect the memorial at Waverley but the churchwardens of St James' refused permission for the memorial tablet.

Most of Fisher's relatives were excluded from the will. One nephew, Thomas Clarkson, a shoemaker who had been apprenticed to his uncle as a youth, received £300 and the children of one niece, Sarah Spratt, shared in the proceeds of a £2,000 trust fund payable when they turned 21 or married. Two of the excluded nephews, William and Henry Clarkson, petitioned the University Senate, claiming their names had been 'accidentally omitted' from the Will and seeking 'favourable consideration' as they were in poor circumstances. The Senate declined to act.

During 1885 and 1886 Fisher's executors sold his various properties and called in his mortgages. He owned property in Darlinghurst, Darlington, Botany, Balmain, the North Shore and elsewhere. The Darlinghurst properties were the most valuable, comprising 20 buildings centred on the intersection of Burton and Palmer Streets, close to Taylor Square. The university eventually received just over £32,000 – approximately $3 million in current values.

The library

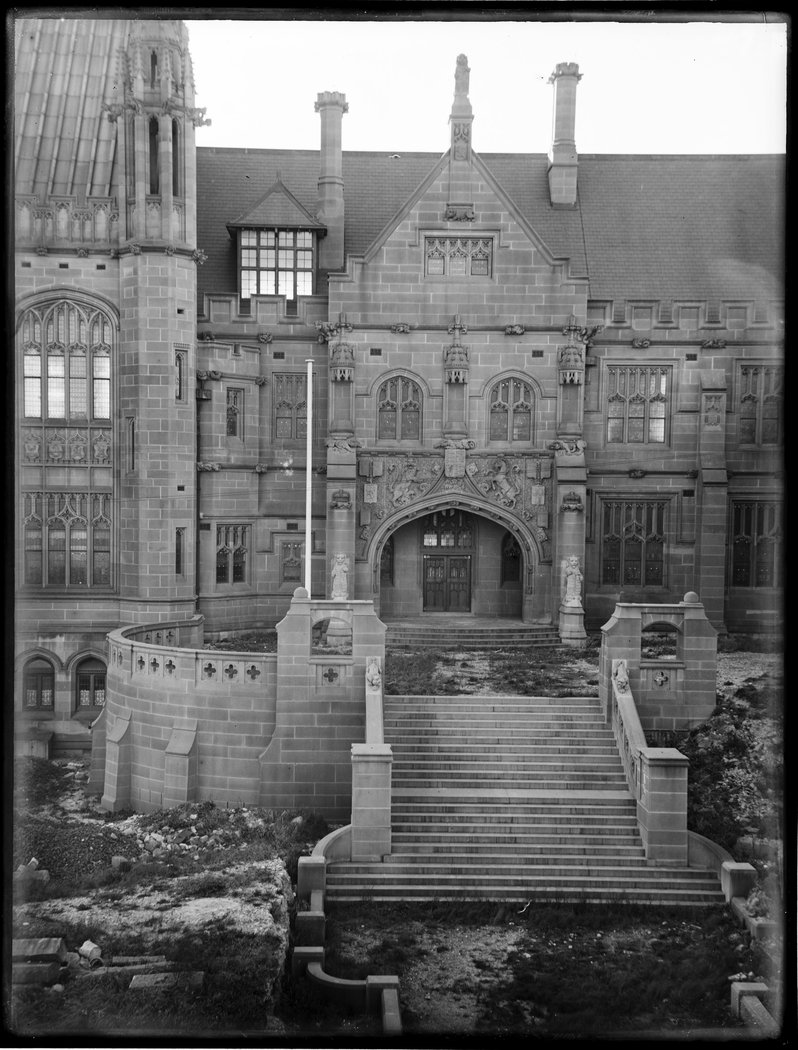

[media]The university struggled to decide how to spend the Fisher bequest. The Chancellor believed it should be used to erect a library building and endow the office of librarian, but the vice-chancellor and the library committee wanted some reserved to purchase books. Resolutions, amendments, and rescission motions on this subject were features of Senate meetings during 1887–1889 until a final decision allocated £20,000 for a new building. The state government was asked to contribute a corresponding amount for buildings annexed to the library, such as a museum for the Nicholson collection of antiquities, a student refectory, student common rooms and residences for the librarian and registrar. The sum of £10,000 was allocated as a perpetual book fund. Negotiations with the government about its contribution for buildings dragged on until 1900 but eventually it was agreed that the government would meet the entire cost of a new library building, including space for a museum and student refectory.

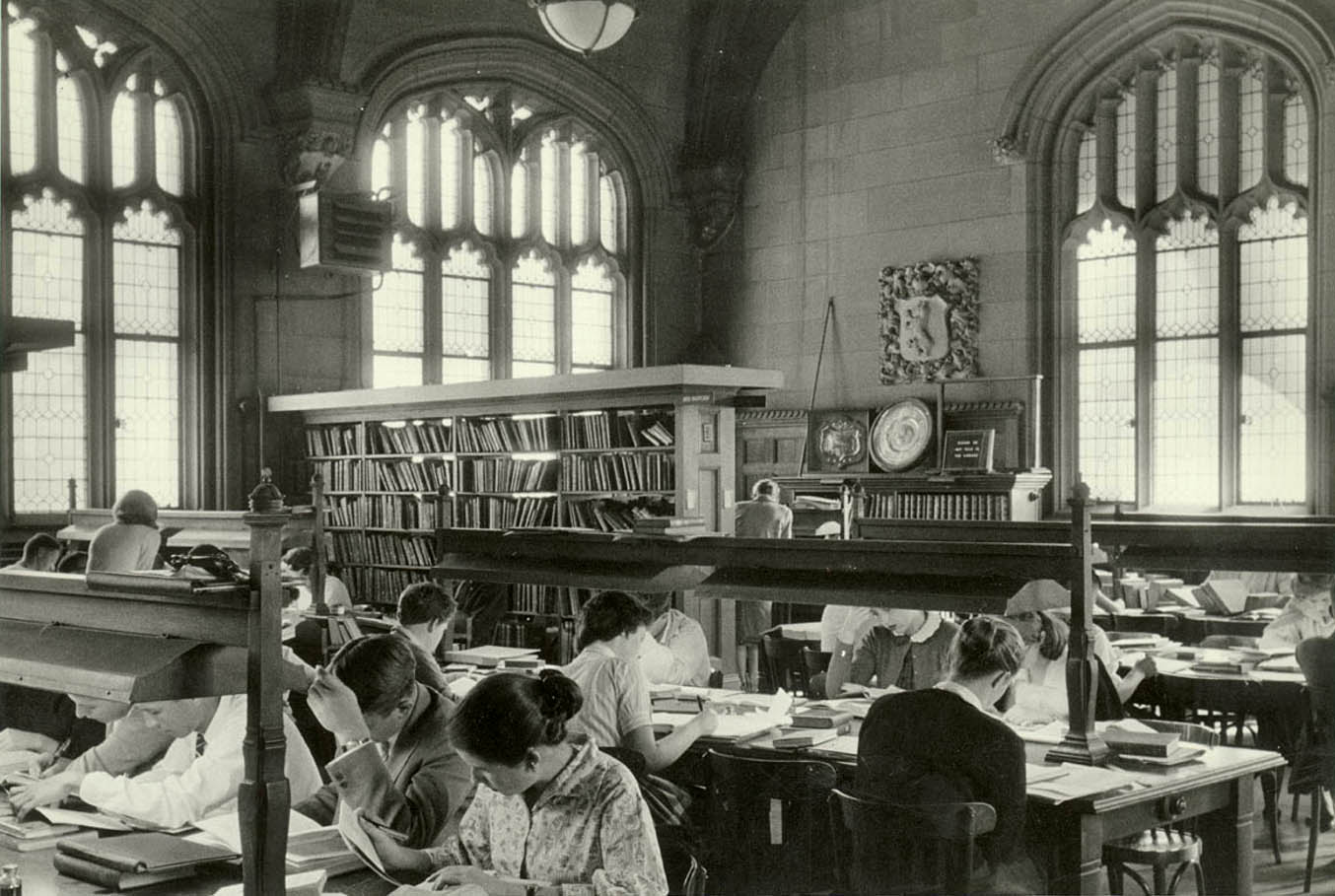

[media]The Fisher Library, in the south-west corner of the University's quadrangle, was opened in 1909. Within 50 years it was no longer adequate for its purpose and in 1963 a new building was opened and the name Fisher Library was transferred to it, maintaining the link between the university library and its most significant benefactor. The original library reading room was re-named MacLaurin Hall to commemorate Sir Normand MacLaurin, chancellor from 1896 to 1914.

[media]By agreeing to meet the full cost of the erection of the first Fisher Library, the state government enabled the university to retain the Fisher bequest in its entirety for the purchase of books and periodicals, although financial problems forced the diversion of at least part of the income of the fund to pay staff salaries from 1893 to at least 1937. Income from the Fisher Fund is now reserved for the purchase of collections and other significant materials that cannot be afforded from the library's normal allocation within the university's annual budget.

Further reading

Barff, HE. A Short Historical Account of the University of Sydney. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1902.

University of Sydney Archives, Fisher Papers.

Gray, Nancy. 'Fisher, Thomas (1820–1884)' in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, 1972.

Radford, Neil A. 'Thomas Fisher and the Fisher Bequest' in Neil A Radford and John Fletcher, 'In Establishing and Maintaining a Library': Two Essays on the University of Sydney Library. Sydney. Sydney: University of Sydney Library, 1984.

Notes

[1] Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, Registers of Births, Deaths and Marriages, St John's Church, Parramatta, A4381

[2] State Records NSW, Probate Office, Supreme Court of NSW, Will of John Fisher, No 759, Series 1

[3] City directories for 1843–1873 list him as occupying these premises, variously numbered 310 and 176 Pitt Street, as a bootmaker, boot and shoemaker, and boot and shoe warehouse. Joseph Fowles Sydney in 1848/from drawings by Joseph Fowles (Sydney: J Fowles, 1878), 41

[4] University of Sydney Archives, Fisher Papers. This description appears on his receipts.

[5] University of Sydney Archives, WM Manning, Chancellor's Address. University of Sydney Commemoration, Saturday 19 July 1879, 4–5

[6] University of Sydney Archives, Fisher Papers, Will of Thomas Fisher, 29 October 1880

[7] Waverley Cemetery, Sec.2, Grave 175

[8] 'Gold Hoard May Lie in Old House. Mystery of £100,000', Sunday Telegraph, 7 September 1952, 11

.