The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Culture and customs

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Culture and customs

In the early twenty-first century the values, practices and institutions that shape Sydney's cultural life reflect the city's binding entanglement in a web of modern, cosmopolitan, culture. Through complex processes of transmission, cultural values and institutions are imported from almost everywhere in the world, and re-worked and adapted to meet the requirements of this rapidly growing and always changing city. Yet the winding, narrow and haphazardly laid-out streets of those sections of Sydney that constitute the areas of earliest European settlement – including The Rocks and that part of the city stretching several hundred metres south from Circular Quay – exist as reminders of an older and very different Sydney, and of a pre-industrial culture brought here by free and convict settlers from the British Isles. [1]

Sydney's pre-industrial culture was comprehensive and public, a culture in which most European inhabitants participated as players, performers or spectators. After 1850, however, a series of distinct but overlapping cultures emerged, imported and adapted from Europe and America to meet the needs of a modern, class-based city. This essay explores the characteristics of the city's pre-industrial culture, and maps its replacement by a set of sometimes conflicting modern, urban cultures.

This essay also shows how new forms of cultural transmission, including cinema, radio and (ultimately) television, facilitated a process of cultural resolution after World War I even as new forms of culture based on ethnicity, age and gender emerged to produce a different mix of cultural diversity. Popular culture, interpreted to mean that which is widely practised, watched, heard and read, generally accepted and approved by the majority, is the main although not the exclusive focus of this article, which describes and interprets those cultural values and institutions that exerted influence on the lives of the majority of Sydneysiders.

Pre-industrial culture in England

Late eighteenth century English society retained strong pre-industrial characteristics. Work was largely seasonal, with times of intense labour followed by extensive periods of idleness. The task rather than the clock regulated each working day, which was also punctuated by long, irregular pauses for drinking and talking. [media]Leisure too, followed traditional forms, centring on fairs and wakes (which were celebrations held to mark the anniversary of the dedication of the local church); the alehouse with its accompanying recreations like dancing; sporting activities such as cricket, (folk) football, horseracing and bare-knuckle prize fighting; and blood sports, of which cockfighting was the most common.

In London, theatre was also popular and was attended by men and women from all ranks and classes. Certain values and characteristics underpinned all of these diverse leisure activities. In the first place, riots and expressions of disorder were commonplace at occasions of public leisure. Second, gambling was endemic – spectators at cricket matches were as likely to bet on the results as frequently as those who watched horse races. Third, Englishmen and (sometimes) women from a range of social backgrounds attended these cultural events, reflecting the existence of a shared public culture.

Yet at the time of the settlement of Sydney Cove, England was also a nation marked by economic change and social dislocation. This was a consequence of the emergence of a factory system in the north of England and the resulting creation of an urban working class, and of the spread of agrarian capitalism marked by a quickening process of enclosure and the dispossession of large numbers of tenant farmers. Wage relationships began to replace those based on patriarchy, and enclosure took away the traditional rights of villagers and farmers to gather wood and graze stock on the fast disappearing commons. The old notions of an organic and hierarchical society bonded by the principle of deference were increasingly disregarded. [media]Plebeians seized on occasions of public recreation to riot against and mock those who stood for authority, while the gentry believed that in London all semblance of law and order had vanished. Many of those who came to Sydney as convicts were the products of this dislocation and the inheritors of a culture of defiance. [2]

Constructive recreation in the colony

Despite the cultural baggage that the free settlers and convicts brought with them in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, English cultural practices, rituals and institutions were not immediately replicated in early Sydney. It was the responsibility of the authorities to create a place of punishment, rather than to recreate a cultural environment that was potentially conducive to hedonism and disorder. What persuaded the early governors that the problems of law and order were particularly acute was the arrival of Irish convicts in the 1790s and after, for they were considered to be possessed of 'barbarous ignorance, and total want of education'. [3] The Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 confirmed the colonial government's view that Irish felons were seditious. [4]

In the end, Governor Phillip and his successors were obliged to permit an ever-increasing range of recreational and sporting activities. Partly this was because the officers, and later free settlers, were active in promoting certain sports – horse racing and cricket in particular – as a means of claiming legitimacy as a colonial gentry. They were intended as tangible demonstrations that these men possessed the requisite characteristics of manliness and paternalism. Moreover, in the absence of organised pastimes, the convicts reproduced old country habits in the form of gambling and drinking. They manufactured their own playing cards and frequented taverns and sly grog shops, despite instructions to the contrary. [5] It was in this context that the governors sought to provide alternative and 'constructive' recreations.

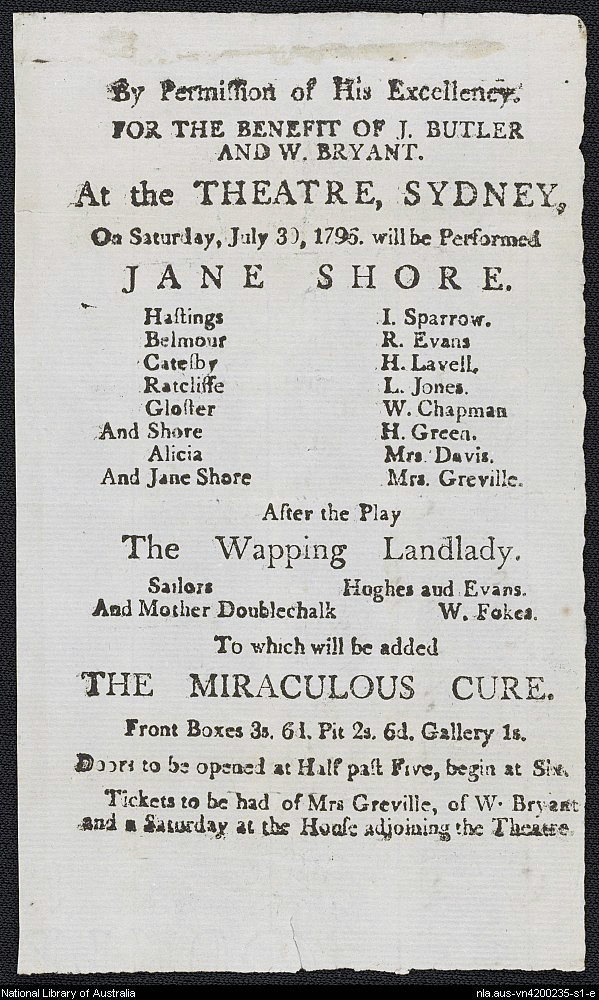

[media]So, with the intent of introducing recreation that served 'rational' and 'educational' purposes, in 1796 the authorities allowed a group of 'the more decent class of prisoners, male and female' to open a playhouse in The Rocks. Over the next eight to ten years the company presented a number of contemporary English plays, including comedies and tragedies, as well as at least one performance of Shakespeare's Henry IV (Part 1). In the tradition of English audiences, the Sydney playhouse theatregoers sometimes proved rowdy and disorderly. [6] Not for the last time, the authorities found that channelling Sydney's cultural direction was no easy task.

Unruly but popular pastimes

Because they enjoyed the patronage of officers and the nascent gentry, a range of pre-industrial institutions and pastimes with no pretensions to serving educational purposes also became common and popular. Alehouses and inns were soon as common a feature of the colonial as they were of the English landscape. Phillip granted the first two licences to sell liquor in 1792 and by 1811 there were 40 spirit licences in Sydney and 27 beer licences scattered through the colony. [7]

Cockfights were held in Sydney from the earliest years of settlement, with Brickfield Hill and the wharf areas serving as the main venues. From about 1810 they took place in public houses both in Sydney and Parramatta, while subsequently Redfern and Richmond became the most frequent sites of cockfights. [8]

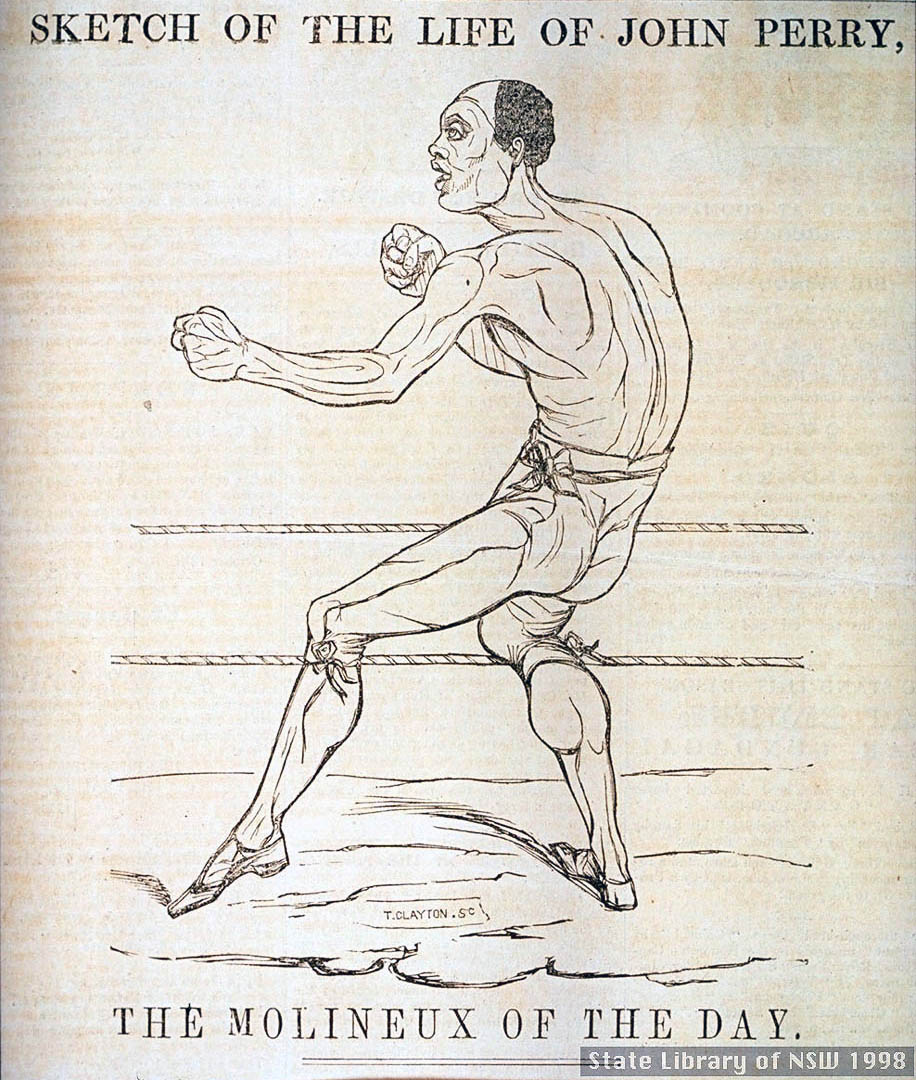

[media]The first bare-knuckle contests held in Sydney were informal grudge matches, although the sport became institutionalised in 1811 when a fight between James Parton (known as Bellinger) and Charles Sefton was fought under the rules of the English prize ring. Contests organised by publicans and featuring English immigrant fighters became even more commonplace in the 1820s. However, when the authorities threatened to declare the venues disorderly houses and prosecute the contestants under the Vagrant Act, the fights were moved to more isolated places on the north shore and the Duck and Georges Rivers. [9]

There is slight but intriguing evidence that Aboriginal people attended some of these early sporting and festive occasions, in particular the Killarney Races at Windsor. More comprehensive evidence exists to indicate that considerable numbers of Europeans attended the pay-back contests organised by Eora men, most commonly at the Brickfields ground, a space also used for cockfights and prize fights. Perhaps the Europeans identified such contests simply as extensions of their own blood sports. [10]

One early Sydney pastime which received official sanction and emerged as perhaps the most popular was horse racing. It was given a fillip in the 1790s with the importation both of Arab and thoroughbred horses. [media]Most early contests consisted of match races on the public roads, although a racecourse existed at Green Hills near Windsor by 1797. Organised by the 73rd Regiment and sponsored by Governor Macquarie, the first official horse race meeting was held at Hyde Park in 1810. Thereafter the Hyde Park races became more or less an annual event, although in line with John Bigge's recommendations to establish a more disciplined and ordered society, Governor Brisbane halted official meetings between 1821 and 1825.

[media]Race meetings recommenced first at Hyde Park and subsequently at courses at Bellevue Hill (1825), Grose Farm (1827–30) and Parramatta (1827–34). The formation of the first Sydney Turf Club (1825) and its bitter rival the Australian Racing and Jockey Club (1827), organised by some of the colony's richest and most powerful figures, bore further testimony to the popularity of and prestige attached to horse racing. [11]

In promoting theatre and horse racing in particular, the authorities had sought to divert the population from drinking and gambling, but such ambitions were doomed to failure. Despite the governor's instruction that they were not to drink or gamble, the convicts attending the first Hyde Park races become so intoxicated that they were unfit to work for several days, while gambling booths run by card and pea-and-thimble sharps became standard at all race meetings. Gambling on cockfights, prize fights and even cricket matches became endemic. By the twenties and thirties a male sporting subculture had emerged, a colonial replica of London's 'the fancy'. Led by such sporting 'gentlemen' as WC Wentworth and John Piper, its rank-and-file plebeian members haunted the pubs of Sydney and lived from the proceeds of gambling. [12]

In the 1830s and 1840s the traditional pastimes of cricket, horse racing, cockfighting and prize fighting remained enormously popular. Upper-class women from impeccable backgrounds were limited to a relatively few public leisure activities – as spectators at cricket and horse races, as members of audiences in theatres and as participants at Government House functions, especially balls. Plebeian women also attended the theatre and horse races, although they were not permitted into the grandstands built especially for 'ladies'. They also found amusement in the dance halls attached to public houses, for which they were sometimes undeservedly labelled 'prostitutes'. [13]

The organisation of leisure

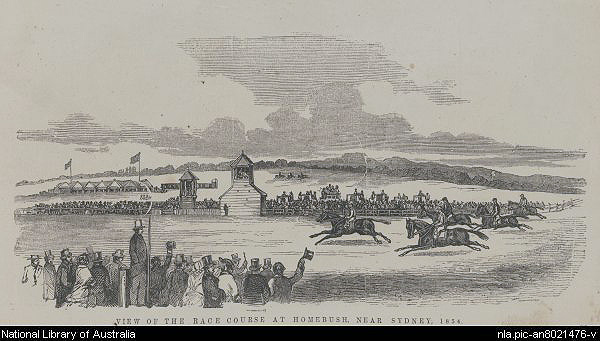

There were signs in this period that leisure activities were becoming more formally organised and institutionalised. [media]For example, the formation of the Australian Jockey Club in 1842 allowed the conduct of regular race meetings at Homebush until 1859, when the club moved its meetings to Randwick. The decline of Sydney's convict population also encouraged governors to allow the full range of public recreations.

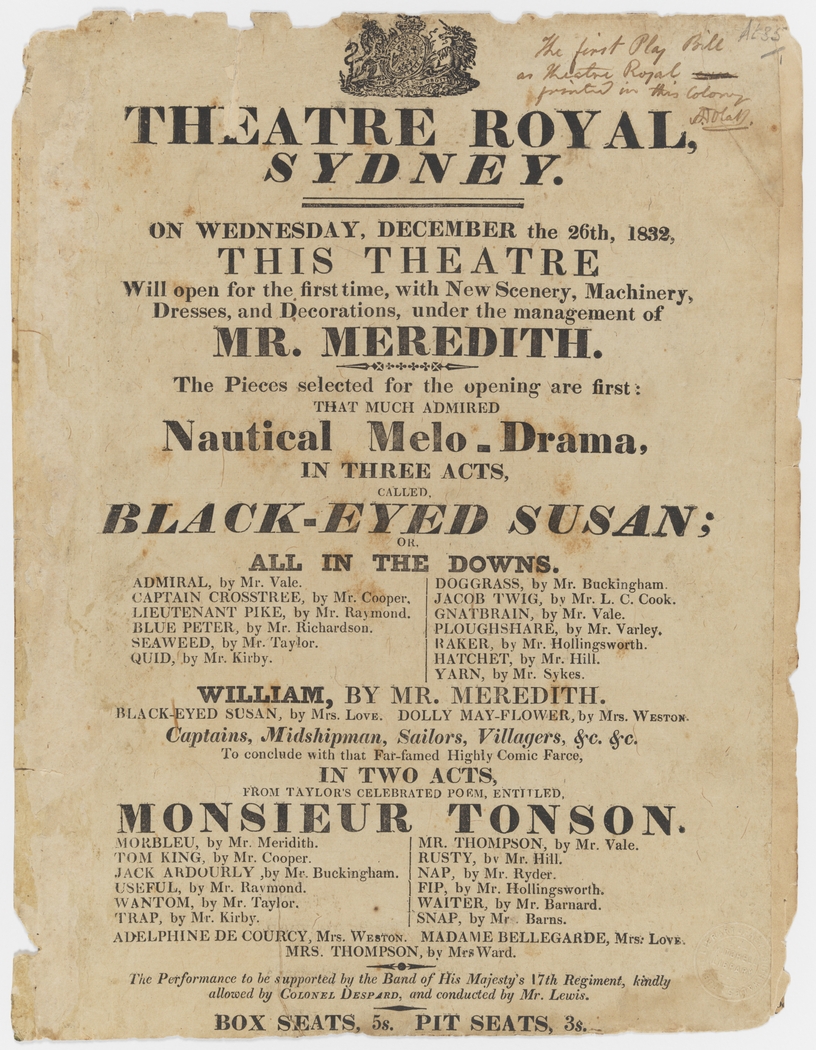

[media]When Barnett Levey applied to Darling for a theatre licence in 1828 it was denied, but in 1834 Bourke approved the re-introduction of theatrical performances. The small but vocal number of Sydney's evangelical Christians condemned this theatrical revival but its supporters claimed it provided 'rational amusement', an alternative to gaming and drinking.

The early performances at Levey's Theatre Royal on George Street suggested that perhaps the evangelicals were right, for rowdiness was common in the pit and gallery, and prostitutes were regular customers. [14] Although regular performances of Shakespeare's plays re-enforced the notion of the theatre as a place of 'moral instruction', critics argued that the staging of comedies like Moncrieff's Tom and Jerry; or Life in London, which celebrated London low-life, simply encouraged convicts and emancipists to return to lives of crime. [15]

In the tradition of the London stage, programs at the Royal not only featured a main play, but light entertainments between acts as well as afterpiece farces. The mixed program was needed to cater to a diverse audience. [media]However, with the demise of the Theatre Royal, Joseph Wyatt's Pitt Street theatre, the Royal Victoria (founded in 1838) developed a reputation for providing 'worthy' entertainment. The audiences became well behaved, the upper and middling orders began to attend more regularly and opera came to feature on the program. The bifurcation of the Sydney stage was reflected in the fact that popular entertainments featuring circus acts and 'nigger songs' were no longer performed at the Royal Victoria but rather were now to be found in the city's newly founded music halls, which catered specifically to plebeian audiences. [16] This development signified the end of a shared public culture and the emergence of entertainments catering to specialised audiences.

Urban culture emerges

The gold rushes and the influx of immigrants in the 1840s and 1850s helped to transform Sydney and its cultural life. The city's population rose from 54,000 to 648,000 between 1851 and 1914. In this period the incomes of unskilled Sydney labourers remained low but the real wages of semi-skilled and skilled workers improved. As well, accompanying this development was a reduction in working hours, the establishment of more public holidays and, in the first decade of the twentieth century, the institutionalisation of the Saturday half-holiday. These factors facilitated the development of a modern, urban popular culture.

Moreover, the pre-industrial working city, in which people of different classes lived close together and in which people's workplaces were also their homes, disappeared. [media]The development of public transport allowed work and home to be separated and the emerging middle class to live in more distant suburbs, removed from the city and the less prosperous working classes. [17]

By 1890 the poorer working people were housed in an inner city zone while the more affluent workers enjoyed less crowded and more sanitary conditions in the eastern, southern and western suburbs. The middle classes were found in the outer suburbs of Drummoyne, Randwick and Canterbury while the very rich lived along the bays and peninsulas stretching to the heads. These suburbs symbolised a wider cultural differentiation, since those who considered themselves 'respectable' shunned city culture in favour of one based on a pastoral ideal, moral reform, 'muscular Christianity' and rational recreation.

In this period, then, Sydney's culture was shaped by modernisation and differentiation. Changes in sport and the form of theatre strongly reflected these modernisation impulses. Cricket, football (in the form of rugby union and rugby league) horse racing and boxing were all subject to the standardisation of rules, the organisation of regular competitions, the appointment of professional administrators, the appearance of professional players using modern equipment, and the emergence of a sporting press which not only provided descriptions of major sporting events but listed statistics measuring the performance both of teams and individual sportsmen. From the mid 1890s, in particular, the sporting journal Referee became the bible of Sydney's sports supporters.

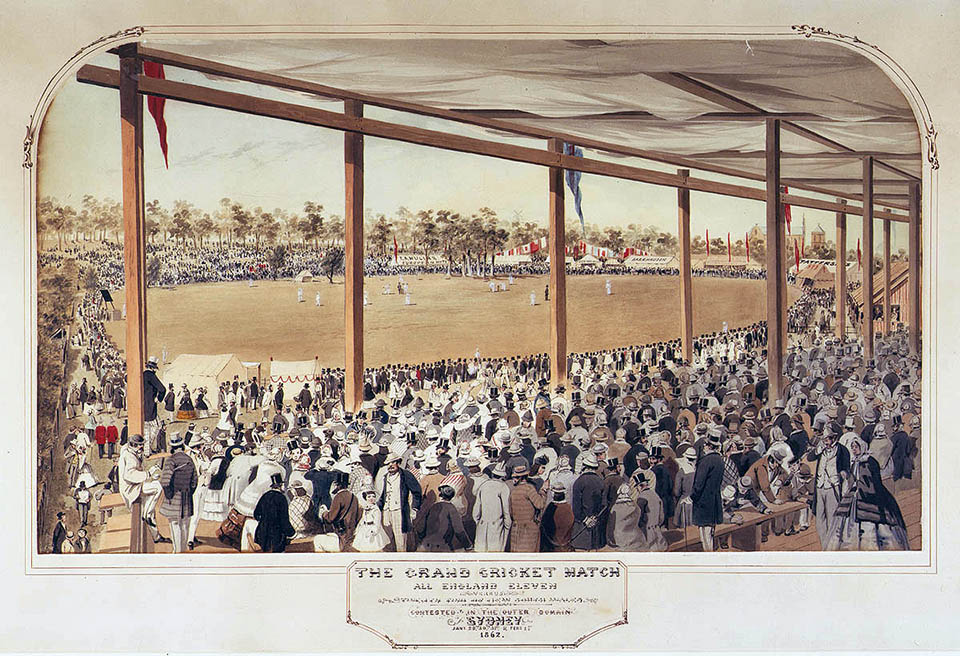

Cricket

Cricket was least subject to modernisation. Although club and inter-colonial matches were played in Sydney from the 1850s, there was no regular Sydney club competition or inter-colonial competition until the early 1890s. Cricket authorities categorised Australian players as amateurs, even though they received payment for 'expenses', which in practice made them semi-professionals. To meet these 'salary' costs, together with those associated with organising the game at local, colony and international level, the cricket authorities began to enclose grounds and charge entrance fees. This practice was instituted at the first inter-colonial match played at the Domain in 1857 and continued at the Sydney Cricket Ground when it opened in 1878. [18]

Football

Sydney's first rugby club, formed by students from the University of Sydney, was organised in 1864 and a regular Sydney competition was inaugurated in 1871. Rugby remained a sport for players rather than spectators and, because it was shaped by an ethos of muscular Christianity that emphasised the moral value of team sports, it also remained a determinedly amateur recreation. [19] For this reason it did not follow the path of Victorian Rules football, which became a hugely popular professional sport, reflected in the large crowds of spectators who attended games. But in 1908, following the example set by the Northern Union in England in 1895, a breakaway professional rugby league competition was established. [media]The teams from Sydney's inner city working-class suburbs, including Glebe, Balmain and South and North Sydney, consisted of working men who needed compensation for time lost from work due to playing obligations and injury. Almost instantly, rugby league became a popular winter spectator sport, providing working people with a sense of local identity in the face of the anonymity of a modern and growing city. [20]

Horse racing

It was horse racing that became Sydney's dominant sporting pastime. In the 1860s and 1870s, when the Australian Jockey Club (AJC) was the only major provider of races in Sydney, meetings were held over a few days in each of spring, summer, autumn and winter. [media]But from 1884 a series of profit-making proprietary and pony clubs and racetracks were established at Canterbury, Rosehill, Moorefield, Warwick Farm, Kensington, Rosebery, Brighton, Ascot, Lillie Bridge/Epping (at Glebe) and Victoria Park (at Zetland).

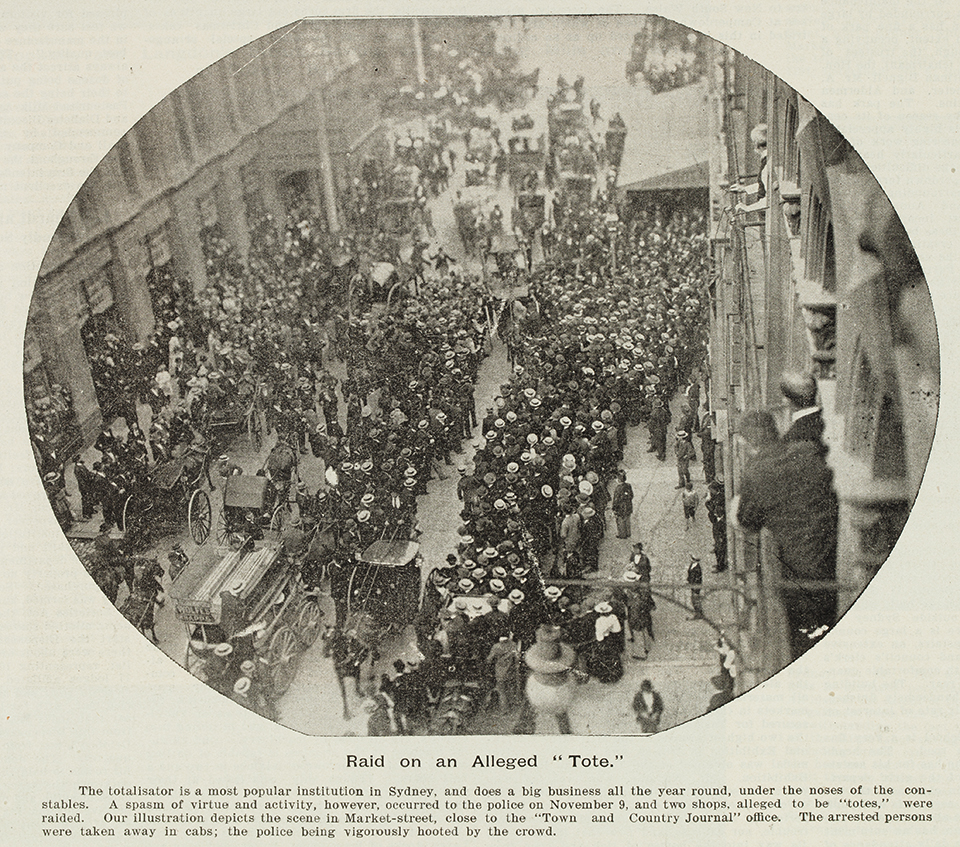

Sydneysiders [media]could now attend the races almost every day of the week, travelling comfortably by train or tram to courses featuring modern grandstands incorporating restaurants and bars. One significant result was a rise in illegal gambling, with 31 SP (starting price) betting shops operating in Pitt Street alone in 1901. Most of the spectators were men, although middle and upper class women were lured to Randwick by the social status associated with the Paddock and Members' enclosures. Working class women were reluctant to deal with bookmakers who dismissed them as 'silver bettors', but with the establishment of totalisators on Sydney courses in 1917 the proportion of women attending and betting on the races increased. [21]

Theatre

Along with horse racing, the theatre was the key strand of commercial leisure in Sydney in this period. Both Sydney and Melbourne were part of the international touring circuit and theatregoers in both capitals were renowned as highly enthusiastic and highly critical. Entrepreneurs like JC Williamson and Harry Rickards imported popular plays from London and New York, persuaded star overseas actors to tour the antipodes and used modern advertising techniques to publicise both plays and performers.

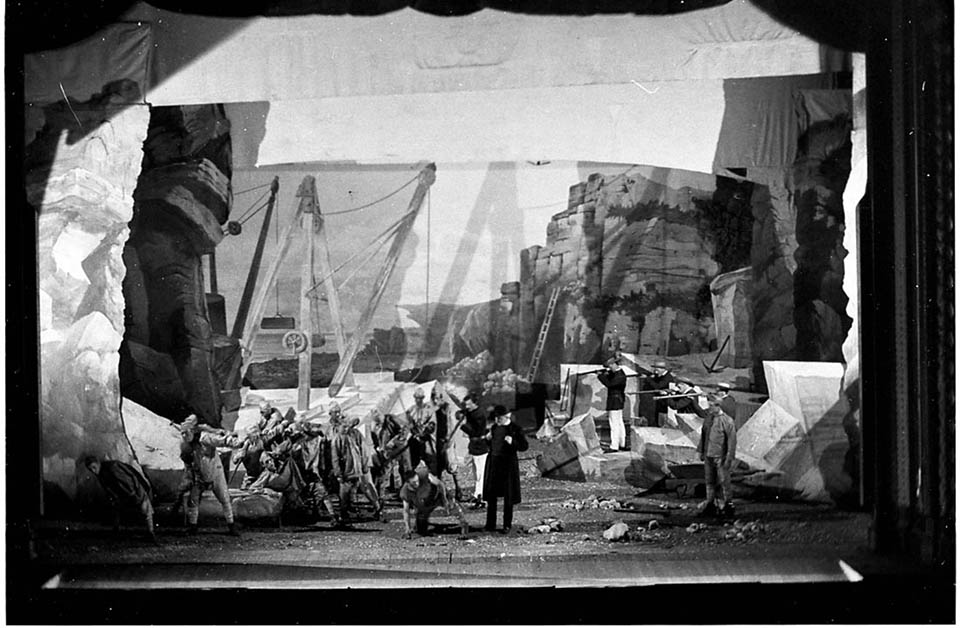

[media]Melodrama became the most popular genre amongst Sydney theatregoers and dominated the programs at such mainstream theatres as the Royal Victoria, the Royal, Her Majesty's, the Royal Standard and the Criterion. For the most part, overseas melodramas predominated with East Lynne and Uncle Tom's Cabin proving the most popular plays. However, from the 1880s melodramas with local settings, which emphasised pride in progress, nostalgia for a lost and golden rural past, and an understanding of history that presented the convicts as victims not villains, became more common. For the Term of His Natural Life, first presented in Sydney by the Dampier Company at the Royal Standard in 1886, incorporated all three themes, which perhaps explains its enduring popularity both as a play and subsequently as a film. [22]

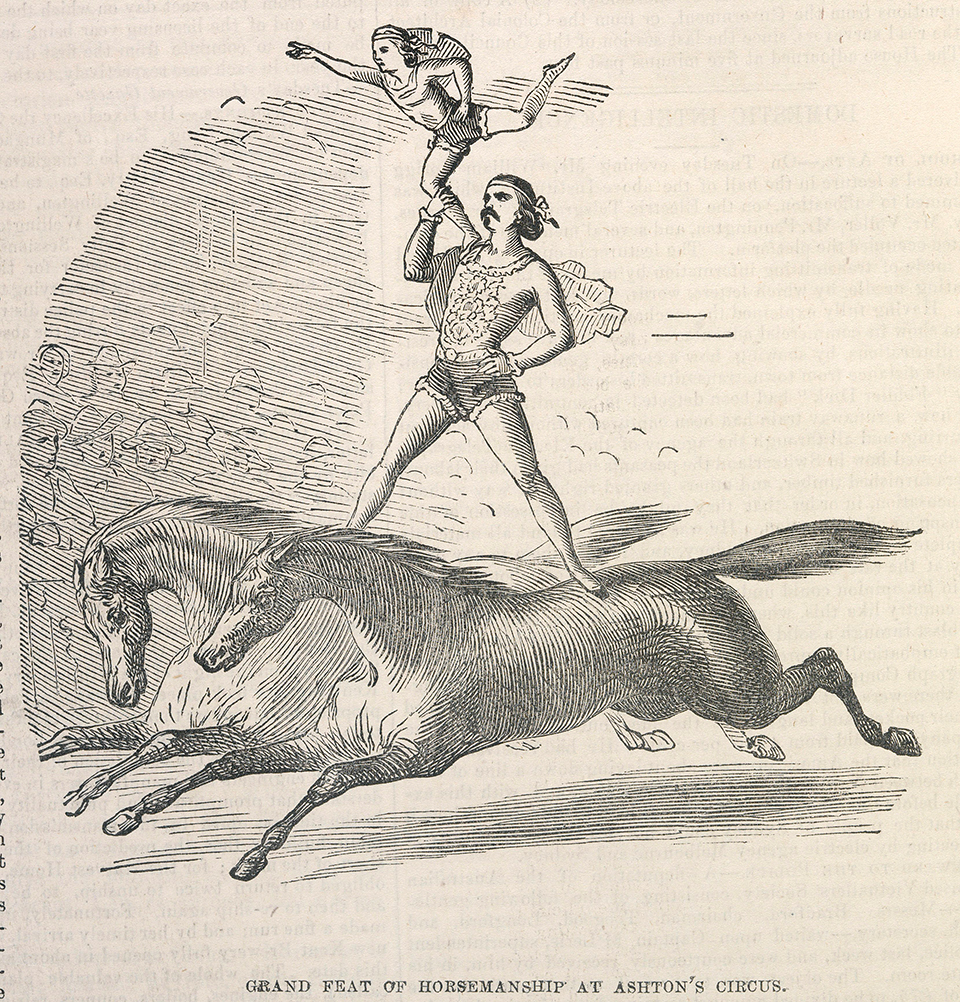

[media]Halls like Sydney's School of Arts housed visiting and local minstrel companies, while large circuses like Cooper and Bailey's (1876) pitched their enormous tents in Sydney's Haymarket. The minstrel troupes, with their popular American songs and a 'yankee style' humour often laced with local allusions, were early conduits for American popular culture. The vaudeville theatres established in Castlereagh Street in 1893 by Harry Rickards (the Tivoli) and in 1906 by James Brennan (the National Amphitheatre) included English and Australian acts and material. But they were also venues where audiences familiarised themselves with the latest American songs and sketches. This material often valorised city life by pointing to the excitement and opportunity it offered, while at the same time challenging what seemed to be the increasingly anachronistic nature of Victorian sexual morality.

However, although vaudeville epitomised city culture, its ascendancy was short-lived. The very first 'cinematographe' shown in Sydney was included as one of the 'turns' at the Tivoli in 1896, but from 1906 halls like the Lyceum specialised in films only. By 1914 picture theatres had spread to the suburbs and began to attract audiences away from the live venues. The first golden age of Sydney's theatre was about to end. [23]

Middle-class culture

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Sydney's middle class was culturally distinct from the working classes. The middle class lived in suburbs segregated from inner Sydney. Whereas working people lived in attached houses, the middle class owned or rented freestanding homes, many of them built in a Queen Anne rustic style, later called Federation. Middle-class Sydneysiders practised a series of elaborate rituals relating to meeting, marrying and dying, designed to exclude those who did not 'belong'. Disturbed by an urban popular culture that espoused recreation for its own enjoyment and that accepted gambling and drinking as part of everyday life, the middle class responded by promoting the virtues of moral reform, amateur sport and physical exercise, and entertainment that was educational. [24] Through a reform campaign in which women played a prominent role, they persuaded the colonial and state governments to pass 'local option' acts. As a result of a poll held in 1907, proprietors of 293 hotels across the state lost their licences. The relatively small number of pubs on the north shore in 2008 is a residual legacy of this anti-drinking campaign. [25]

The Sabbatarian campaign also resulted in the establishment of the 'English Sunday' as a Sydney institution. Theatres were closed and sporting events were banned at publicly owned venues on Sundays. The School of Arts was also shut, although unlike Melbourne the public library and art gallery remained open and trams and trains still ran throughout the day. The commitment to the strenuous life was reflected in a new emphasis on sport and athletics in the major boys' private schools and the institutionalisation of their inter-school competition in 1892. It was also reflected in the emergence of the cult of the 'sporting girl', which stressed that women as well as men benefited from outdoor sports and challenged the Victorian assumption that women were physically unsuited to strenuous activity. The proliferation of golf and bowling clubs throughout Sydney from the turn of the century was a further sign of the influence of this ethos. [26]

In Europe and the United States in the late nineteenth century an understanding of high culture emerged which stressed the superior and absolute moral and aesthetic qualities of great literature, art and music. In this context classical works of culture were no longer considered as essentially providing entertainment – Shakespeare, Wagner and Beethoven were valorised as cultural gods. Such an understanding received institutional expression in the establishment and endowment of art galleries and museums, orchestras, opera and classical drama companies by governments and philanthropists. Sydney's small number of self-appointed aficionados of classical music and drama readily adopted this aesthetic. But the city's elite lacked both the capital and inclination to replicate the European or North American example by funding the institutionalisation of high culture.

[media]The Art Gallery of New South Wales was established in the 1880s but its budget was too meagre to allow it to compete for the works of the 'great masters'. It used its modest financial resources to accumulate a much less expensive collection of Australian art, instead. Belatedly and ironically, the slow decline of 'cultural cringe' and the awakening of cultural nationalism in the decades after World War II led critics to regard some of these Australian paintings as 'masterpieces', worthy to be acclaimed as works of high culture.

A state orchestra was founded in 1916 but only a few of its members were full-time professionals, with the remainder drawn from the staff and students of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. [27] As for opera, fans had to rely on the intermittent visits of overseas companies, culminating perhaps with the Quinlan Company's performance of the complete Ring Cycle in 1913, although Melbourne got it first. [28] Not until after World War II, with the establishment of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust, did high culture find comprehensive institutional support in Sydney and elsewhere.

[media]By 1914 there were clear signs that the campaign to extend respectable culture was waning. A local option poll across New South Wales suggested that voters wanted the status quo, not a further reduction in pubs. But the temperance movement was given a boost with the riotous behaviour of drunken soldiers in Liverpool and Sydney in 1916. In the referendum on six o'clock closing of hotels that followed the riot, supporters emphasised the strategic and patriotic necessity of the measure and insisted that early closing was intended as temporary. Despite this, in 1923 state parliament legislated to make it permanent.

In the nineteenth century pubs [media]had been centres of male plebeian life – working-class women who wished to remain 'respectable' usually gathered at kitchen tables and ordered pitchers of beer from the local. With early closing, the billiard tables and dart boards were removed to accommodate the huge crowds of men that gathered after work for the 'six o'clock swill'. Early closing also inhibited a vibrant Sydney nightlife, for severe restrictions applied to the serving of alcohol in nightclubs and restaurants. The boom in suburban cinema crowds was probably in part the result of six o'clock closing. [29]

Cultural resolution

For much of the nineteenth century then, struggle and opposition marked Sydney's popular culture. But from the end of World War I to the present, resolution rather than conflict has marked Sydney's cultural life. This was epitomised in the increasing movement of the better-off members of the working classes into the newly emerging outer suburbs, and their adoption of lifestyles which once had marked the middle class.

[media]The real estate boom of the1920s was prompted by the demand created by returning soldiers, the ready availability of home loans, improvements in public transport (cars were still beyond the economic reach of most families), and the effective promotion of new estates by real estate agents. Although facilities in new suburbs like Concord were primitive, with no sewerage, footpaths or streetlights, the refugees from the city were attracted by relatively spacious suburban bungalows and the gardens and yards that surrounded them. Through the 1920s and again in the late 1930s, shorter working hours (the 44-hour week was now standard) and higher wages extended the capacity of Sydney's residents for public leisure and recreation. Only during the hardest years of the Depression were Sydneysiders forced to rely primarily on domestic recreations in their own homes.

Sport and gambling

The relevance of cricket to modern Sydney life remained limited because club and interstate competitions had restricted appeal. [media]Although test matches against England attracted large crowds, these were held only every four years. On the other hand rugby league extended its popularity. It became an official public school sport in 1920 and additional clubs were established in the newly settled areas of St George and Canterbury. [30]

[media]Horse racing remained a high profile sport – 90,000 people turned up for Derby Day at Randwick in 1924. However, the industry also underwent a fundamental transformation, when in 1943 the McKell government established the Sydney Turf Club, which subsequently took over the proprietary and pony clubs. The Sydney Turf Club maintained racing on the Rosehill and Canterbury tracks but eventually sold the rest. [31] Ascot became part of Sydney airport, the University of New South Wales was built on the Kensington circuit and Victoria Park became the site of a factory and subsequently of a housing development, the old totalisator building standing as the former track's only remaining racing relic.

Nevertheless, gambling as a Sydney pastime did not lose its impetus or its attraction. SP (starting price, or off-course) betting in pubs and corner shops remained rife, and was given a stimulus by the introduction of race broadcasting on radio in 1926. The establishment of harness racing and, more particularly, greyhound racing provided additional opportunities to gamble. [media]Harness racing was not particularly popular but the greyhound meetings organised at Harold Park in 1927 by the appropriately named 'Judge' Alfred Swindell drew crowds of up to 30,000, mostly working-class men. [32] Although the conservative opposition promised to take action against the sport, when it came to office it failed to carry out its promise, a sign that gambling revenue was already essential to a balanced state budget.

Theatre, cinema and radio

Live theatre struggled to compete against the new forms of entertainment provided by radio and cinema in the interwar period. Entrepreneurs like JC Williamson and Benjamin Fuller sought to cultivate a specialised upper middle class audience with musical comedy programs like Rose Marie and The Desert Song, presented at the Royal, Her Majesty's and the Empire.[media] Both in the suburbs and the city, vaudeville gave way to cinema, especially with the arrival of the talkies in 1929, symbolised by the conversion of Fuller's National Amphitheatre ('the Nash') into the Roxy and then Mayfair picture theatre in 1930. The old Tivoli was closed, although for some years two local performers, Queenie Paul and Mike Connors, ran vaudeville programs, first at the Haymarket Theatre and subsequently at the Grand Opera House, which they renamed the Tivoli. In 1934 the Tivoli passed into the hands of Frank Neil and in 1944 David Martin took control. But the opera and musical comedy programs presented at this Tivoli stood as evidence that vaudeville was no longer a key strand in the web of Sydney's culture.

With the establishment of programs dominated by a feature film, rather than a series of short films, cinema-going emerged as a prime leisure activity not only in the city but also in the suburbs. Matinees often drew women bent on combining a trip to 'the flicks' with shopping, while evening programs attracted courting and married couples. [33] [media]In this era, Hollywood also produced 'blockbuster' pictures designed to be shown at grand cinemas like the State Theatre in Market Street with its gothic entrance, marble staircase, art gallery, period lounges and aquarium. But the American studios failed to make sufficient big pictures to keep the State supplied and its programs came to feature both films and vaudeville, the latter introduced to justify its high admission prices.

American influence

[media]During World War II, the need to meet the rest and recreation requirements of so many American servicemen muted the wowser voices, and restrictions placed on the public recreations of Sydneysiders were far fewer than those introduced in World War I. However, the presence of American soldiers did little to hasten Sydney's transformation from a provincial British to a cosmopolitan and more American-influenced city. It remained a relatively dowdy and shabby-looking city through much of the 1950s and 1960s. Physical transformation in the shape of a proliferation of high-rise office buildings came as a result of the good economic times in the late 1960s and through much of the1970s.

[media]In any case, American cultural influence on Sydney long predated World War II. From the 1850s, the popular stage had served as a conduit for American culture to enter Australia, specifically in the form of minstrel and vaudeville performances. In the interwar period, American films dominated Sydney cinema screens while radio became the prime medium for popularising jazz and other forms of American popular music.

Postwar suburban leisure

Life and leisure centred on family and the home became a dominant characteristic of Sydney's culture in the first 20 years or so after World War II. Scarred by their experiences of the Depression and the war, many returning veterans sought refuge in the ever expanding suburbs of outer Sydney, their aspirations to home ownership fulfilled by low-interest War Service Home Loans. Government and industry promoted the nuclear family and the 'Australian way of life' as the virtuous norms and Sydneysiders responded by directing their spending towards homes, gardens and cars.

In [media]suburbia they created new institutions of public leisure to complement and indeed supersede local picture theatres, which in any case were losing patronage as the result of the introduction of television in 1956. Although six o'clock closing was repealed in 1954, pubs could not match the facilities provided by the sporting and ex-servicemen's clubs that sprang up everywhere in suburbia. These provided cheap food, drink and entertainment, and an environment that women found more hospitable than the 'blokey' atmosphere of most hotels. Sydney's first shopping mall, built in the burgeoning suburb of Ryde in 1957, served as the prototype for much more ambitious complexes at Roselands, Parramatta, and Brookvale, complexes which became not only centres of consumption but social gathering places as well. [34]

Anglo-Celtic Australians abandoned the inner suburbs and city centre as places to live and find leisure, with the result that the number of downtown entertainment venues declined. [media]Only three theatres – the Royal, Tivoli and the Empire/Her Majesty's – continued to operate. While some visiting rock-and-roll entertainers played to packed audiences at the uncomfortable and dilapidated Sydney Stadium, many picture theatres and restaurants struggled and some failed to survive. Crowds at sporting events, particularly rugby league matches and horse races, also began to fall in the 1950s. [35] The residual influence of Sabbatarianism, which meant that theatres and pubs were closed and sporting events banned on Sundays, made Sydney a ghost town for one day of the week.

A cultural renaissance

Three factors led to a renaissance in Sydney's cultural life: the arrival of immigrants, first from Europe, and subsequently from the Middle East, South America and Asia; the institutionalisation of high cultural genres, notably opera, ballet and drama; and the use of modern technology and business methods to promote and transform key professional sports.

In the 1950s, recent arrivals from Greece, Italy and eastern Europe, people labelled 'alien immigrants' by contemporary commentators, began to recreate their old world cultures as well as establishing new world communities in the inner city suburbs vacated by the native-born. [36] The result was to add immeasurably to Sydney's diversity of cuisines, religions and cultural rituals. They did much to promote football, known to other Sydneysiders as soccer, as a major Australian sport, forming ethnically based clubs that competed in Sydney, state and eventually national competitions. Anglo-Celtic Australians sometimes derisively referred to football as 'wogball', an unintentionally ironic label, given that football was created on the playing fields of Eton.

[media]The immigrants also gave a boost to high culture, swelling the audience numbers at Town Hall performances by the newly founded Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and later patronising opera performances by the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust's company. Finally, many of the immigrants were accustomed to a 'continental' rather than an 'English' Sunday, and their presence helped shift public opinion in favour of a greater choice of Sunday recreations. In 1966 sporting bodies and cinemas were finally allowed to open on Sundays, although not until 1979 was Sunday trading allowed in pubs. [37]

Public support for the arts

The establishment of the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust by the federal government in 1954, with the aims, not necessarily compatible, of promoting high and Australian culture, as well as providing employment for local performers, composers and writers, led to the institutionalisation of high culture in Sydney. [38] [media]From 1956 there were regular Sydney performances by the Elizabethan Trust Opera Company and from 1962 annual visits to Sydney by the Melbourne-based Australian Ballet. In 1957, the Trust established the Trust Players, which was intended as a national drama company to match the opera troupe. Although it featured classical European drama in its repertoire, the company also performed Australian plays, including Ray Lawler's Summer of the Seventeenth Doll and Peter Kenna's more quintessentially Sydney drama, The Slaughter of St Teresa's Day. Unlike the opera and ballet companies, the Trust Players were not to last. But the principle of state funding of the arts was now firmly established.

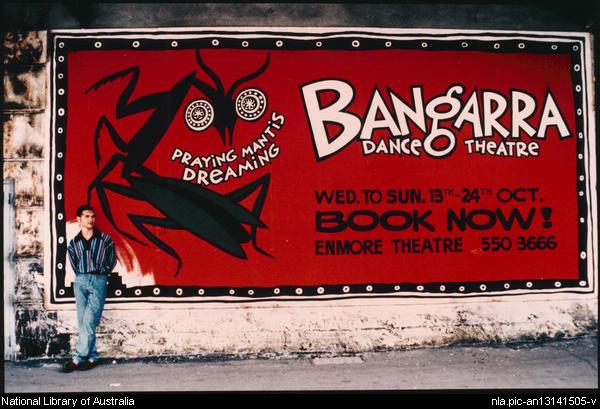

In the 1960s and beyond, the trust and its successor, the Australia Council, provided the funding that allowed companies like the Old Tote, the Sydney Theatre Company, the Nimrod Theatre Company and later Company B at the Belvoir Street Theatre to prosper. Theatre directors, most notably Richard Wherrett, believed that their brief was to develop repertoires of Australian works as well as classical European and American works. [media]At Belvoir Street the managing syndicate also adopted a policy of supporting Aboriginal theatrical and dance productions. It was a sign of the wider recognition of the importance of Aboriginal culture and its significant impact on European mores that plays with Aboriginal content began to enter the mainstream Sydney theatre in the 1980s, most notably Thomas Keneally's Bullie's House and David Williamson's Celluloid Heroes. These theatres nurtured the works of Ray Lawler, Peter Kenna, Louis Nowra, Patrick White, Robyn Archer and David Williamson but also staged plays by Shakespeare, Chekhov, Brecht and O'Neill. A number of the Australian productions, particularly those by Williamson, proved very profitable.

Since the 1950s the repertoires of the national opera and ballet as well as those of the Sydney-based theatre companies have expanded impressively. From the perspective of 2008 it is hard to imagine that in 1956 the programs of the Elizabethan Trust Opera Company were confined to the works of Mozart. Moreover, the venues available for high culture have improved in quality and increased in number. The early performances by Trust companies were at the old Majestic Theatre in Newtown, an unsuitable venue originally built to house melodrama. [media]The opening of the Opera House in 1974 provided halls and theatres for orchestras, as well as opera, ballet and drama companies. In more recent years the spartan performance spaces where the Old Tote Company performed have given way to the Sydney Theatre Company's more suitable drama theatres in Millers Point. The last 40 years have witnessed the second renaissance of Sydney theatre.

The revival of sport

[media]Beginning in the 1960s, professional sport has also regained popularity with the Sydney public. This was achieved through the introduction of business methods into sports management, the establishment of corporate and government sponsorship, and the development of profitable partnerships with television networks. These processes and developments reached an apotheosis in 2000 with the staging of the Sydney Olympic Games. The success of the Olympics was promoted as a sign of Sydney's efficiency, maturity and capacity to handle major projects. It is a sign of the importance of sport to Sydneysiders that the Olympics, rather than educational, economic or (high) cultural achievements, were used as the mark of the city's coming of age as a great international metropolis. [39]

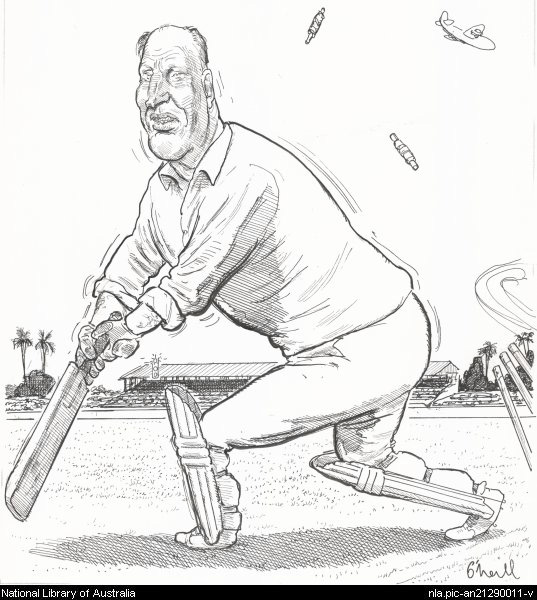

[media]Cricket finally adapted to the rhythms of modern city life when in 1977 the 'Packer Cricket Circus' introduced 50-over day–night matches featuring colourful uniforms and bright lights. For the first time the game attracted large and raucous crowds to the improvised cricket oval at the Sydney Showground. These spectators behaved and looked more like rugby league than cricket fans. [40]

[media]In rugby league, televising games and the introduction of limited tackle rules, which eliminated boring 'bash and barge tactics', combined to promote the game and make it more attractive to spectators. The success of these measures was reflected in a 25 per cent increase in crowds in the late1960s. [41] However, league administrators were slower than their Australian Rules counterparts to fully commercialise their sport.

The Victorian Football League established a national competition in 1982, when the South Melbourne Football Club relocated to Sydney, becoming the Sydney Swans. Faced with this competition and another bout of falling attendances, the league administrators chose to close down some older, inner-city teams like Newtown. By the late 1980s the major source of revenue for clubs was corporate sponsorship, royalties from the sale of endorsed products and television rights. Advertising was now aimed to appeal to men and indeed women from all classes and social backgrounds, and it was successful – by the mid 1990s women made up half the television audience for grand finals. [42] The 'business' path taken by league mirrored developments in America, where major football and baseball clubs are owned by wealthy individuals and corporations, rather than the communities that support them. In keeping with this business approach, in 2006 the South Sydney Football Club passed into private ownership.

In 1995 league survived a takeover attempt by News Limited, but in the new century it faces renewed competition from rival football codes. In Australian Rules football, the Sydney Swans now attract an impressive number of supporters, and with the professionalisation of rugby union, Sydney now fields a team in the international Super 14 competition. Perhaps more importantly, the Football Federation of Australia has now shed its ethnic associations and promotes itself not just as a national but also as the world game. The A-League, successfully inaugurated in 2005, may eventually appeal more to the citizens of a multicultural city like Sydney than a game like rugby league, whose current supporter base is confined to Sydney, Brisbane, Canberra, Auckland and the north of England.

Gambling and drinking

But there is continuity too, for gambling and drinking remain central to Sydney's culture. The decline of evangelical influence in the city since World War II has made the debate about access to alcohol a social rather than a moral one. This is also true of gambling. [media]Once, poker machines were confined to clubs, but the decision to allow them in pubs in 1997 eased access to gambling facilities and changed the function of hotels. This decision was consistent with a series of determinations made by successive state governments since the 1960s.

Off-course totalisators were legalised [media]in 1964, allowing legal and secure off-course betting. Although the facilities provided for punters in TAB offices were sparse and uncomfortable, the introduction of Sky Channel (which televised horse races into pubs and clubs) and the establishment of TAB agencies in clubs and pubs in 1989 gave punters easy access to betting facilities and allowed them to bet in comfort.

Beginning in the 1980s, the spectator facilities at Canterbury, Warwick Farm, Rosehill and Randwick were improved enormously but Sydneysiders no longer ventured to the track in numbers, except at carnival time. Ironically, the number of Sydney residents who watch, follow and bet on horse racing is greater than ever (the annual TAB turnover is in the billions), although most engage in the sport from the comfort of club and pub lounges. Overall, the introduction of new forms of communication and technology, especially since World War I, has allowed the promotion of gambling and drinking as social recreations across the boundaries of class, race and gender, resulting in a major contribution to the process of cultural resolution.

The end of cultural homogeneity

[media]There were factors promoting cultural homogeneity in postwar Australia. But cultural developments were also taking place, which ultimately produced a city marked by new forms of cultural diversity. The federal government's immigration policies meant that the European immigrants of the 1940s and 1950s were followed by settlers from the Middle East, South America and subsequently from Singapore, Vietnam, South Korea and Hong Kong, in particular. The gentrification of the inner city has led to the establishment of ethnically based communities on the edges of the city. However, those arriving with capital, especially immigrants from Hong Kong, have moved immediately into traditionally middle-class suburbs. Eastwood, in northwestern Sydney, was once considered the buckle on the (Protestant) Bible belt, but Chinese merchants and restaurateurs now own the shops along its main street.

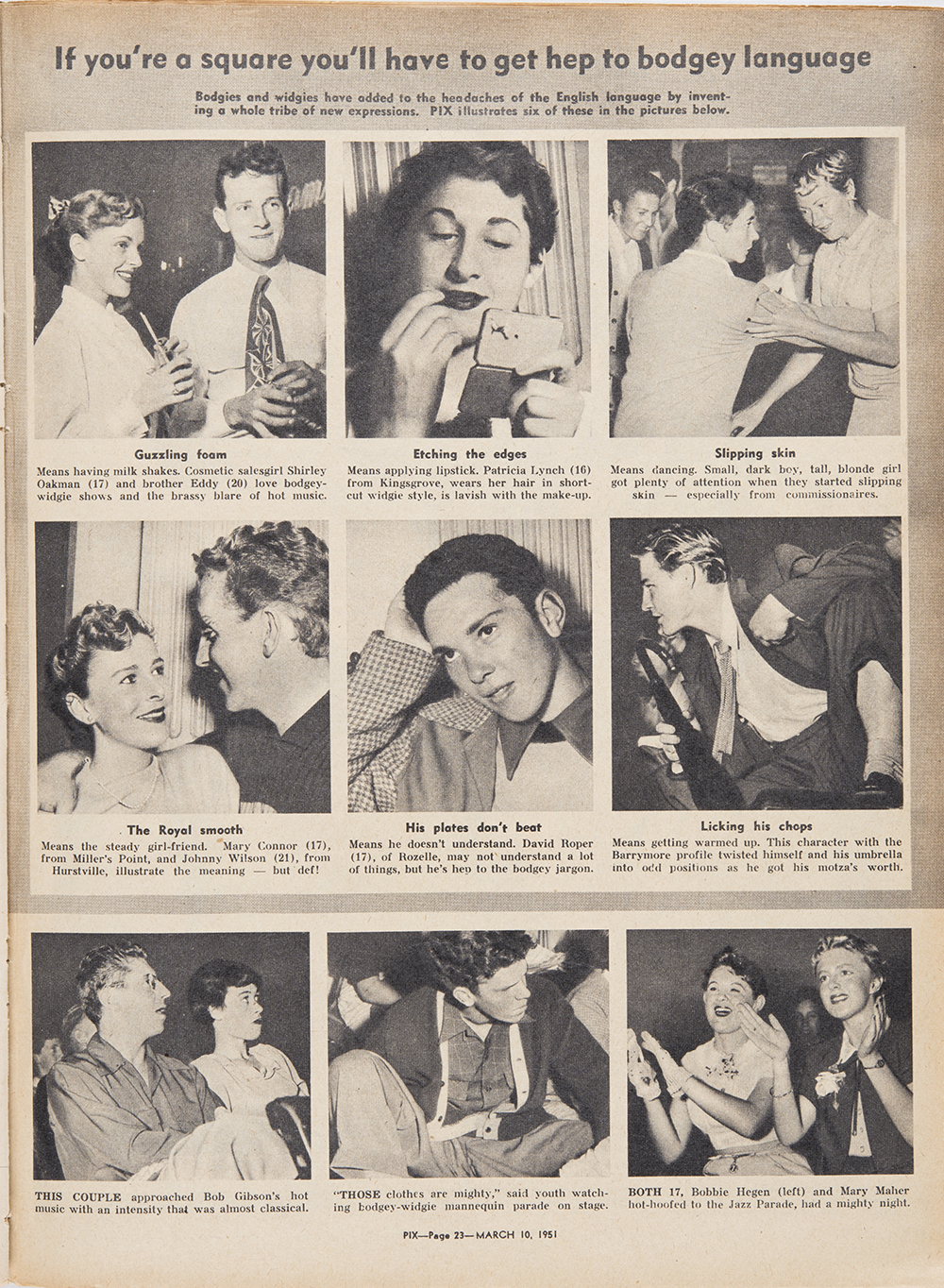

The emergence in the 1950s [media]of a youth culture with its own language, clothing, music and outlook was also a factor in the demise of Sydney's brief era of cultural homogeneity. In the early 1950s the fashion and music preferences of Sydney's teenagers differed only marginally from those of their parents. But rock and roll promoted new forms of music, new sexual standards and new 'bodgie' and 'widgie' fashion styles. Johnny O'Keefe, who began his career singing at dances in working-class suburbs, emerged as the quintessential Sydney rocker, especially when he began to host the television show Six O'Clock Rock in 1959. In the late 1960s this raw and oppositional form of music moved out of the television studios and into live venues like Surf City at Kings Cross and the downtown Civic Hotel. Bands like AC/DC, and Cold Chisel served their apprenticeships on Sydney pub stages before finding fame and fortune internationally. [43]

The importation of the Sydney version of the Californian surfing subculture in the early 1960s was another development in the creation of a separate youth culture. [media]From Maroubra to Palm Beach, its adherents were distinguished by their blonde bleached hair, their stovepipe pants, the 'woodies' they drove, and their abandonment of the work ethic in favour of hedonism, for their coastal safaris were undertaken in search of the perfect wave. [44] Since the 1970s, youth culture in Sydney has undergone a series of multiplications and transformations but it has also remained consistently separate in its forms, values and outlook.

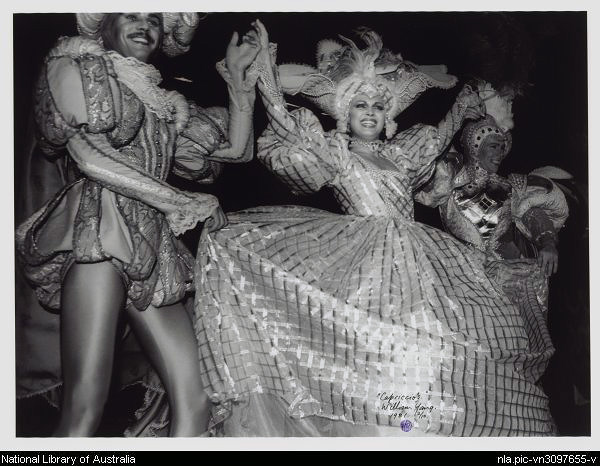

This diversity was also reflected in the emergence of a vibrant, overt and obvious gay culture from the bohemian, demi-monde world in which it had hidden in the back streets of Sydney. [media]In the 1970s gay bars and clubs proliferated along Oxford Street, and in the succeeding decade, the Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, which had originated in 1978 as a political protest, metamorphosed into a tourist attraction luring hundreds of thousands of spectators and millions of dollars in tourist revenue. [45] No form of culture or sport in Sydney, it would seem, was safe from commercialisation. The town on the harbour has truly become the Emerald City.

[media]As someone who spent years living in American cities and witnessed the exclusiveness of ethnic urban ghettos and the violence that seems part of everyday urban life there, I have found Sydney's metamorphosis from a pre-industrial town, to a modern British provincial city, and then into a cosmopolitan and multicultural postmodern metropolis, truly remarkable, and indeed almost miraculous. While some, like those who waved Australian flags and decried Sydneysiders of Middle Eastern descent as 'un-Australian' during the Cronulla riots in 2005, may long for a homogeneous city culture, which in any case was never a long-term Sydney reality, those who live in the city will continue to weave rich, complex and contradictory cultural webs.

Notes

[1] Grace Karskens, The Rocks: Life in Early Sydney, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne 1997

[2] Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra: The Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic, Verso, London, 2000; RW Malcolmson, Life and Labour in England, 1704–1800, Hutchinson, London, 1981; Pamela Horn, The Rural World 1780–1850, Hutchinson, London 1980; James Walvin, English Urban Life, 1776–1851, Hutchinson, London, 1984; RW Malcolmson, Popular Recreations in English Society, 1700–1850, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1973; Douglas Hay, Peter Linebaugh, John E Rule, EP Thompson and Carl Winslow (eds), Albion's Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth Century England, Allen Lane, London, 1975; EP Thompson, 'Time, Work-discipline and Industrial Capitalism,' Past and Present, 38, December 1967

[3] Mitchell Library, Transcripts of Missing Despatches, 1823–1832, MLA 1267, Brisbane to Bathurst, 28 October 1824

[4] Patrick O'Farrell, The Catholic Church and Community in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1977, p 5

[5] DD Mann, The Present Picture of New South Wales 1811, John Booth, London, 1811, pp 54–5

[6] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, A Strahan, London, 1798, pp 448–9; Robert Jordan, The Convict Theatres of Early Australia 1788–1840, Currency Press, Sydney, 2002, pp 57–110

[7] Sydney Gazette, 16 March 1811

[8] Sydney Gazette, 1 January 1804, 12 June 1813

[9] Richard Waterhouse, 'Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting, Masculinity and Nineteenth Century Australian Culture', Journal of Australian Studies, 73, 2002, pp 101–10

[10] James T Ryan, Reminiscences of Australia, George Robertson and Company, nd, pp 114–8; Sydney Gazette, 31 March 1805, 8 December, 15 December, 22 December 1805, 12 January, 19 January, 2 February, 16 March, 23 March 1806, 23 December 1808, 15 January 1809.

[11] Martin Painter and Richard Waterhouse, The Principal Club: a History of the Australian Jockey Club, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1992, pp 2–15

[12] Sydney Gazette, 16 October 1810, 21 October 1833

[13] Evidence of Deputy Superintendent of Police, 7 December 1819, Bigge Transcripts, Box 2, 611–19

[14] Sydney Gazette, 2 July 1833, 3 April 1834

[15] Sydney Gazette, 3, 7 June 1834

[16] Sydney Morning Herald, 28 August, 31 October 1843, 21 September 1844

[17] Shirley Fitzgerald, Rising Damp: Sydney, 1870–1890, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987, p 115

[18] Bell's Life in Sydney, 17 January 1857; Phillip Derriman, The Grand Old Ground: a History of the Sydney Cricket Ground, Cassell, North Ryde, 1974, p 17

[19] Old Times, July 1903, pp 296–9; G Inglis, Sport and Pastime in Australia, Methuen, London, 1912, p 173

[20] Chris Cunneen, 'The Rugby War: the Early History of rugby league in New South Wales, 1907–1915', in Richard Cashman and Michael McKernan (eds), Sport in History: the Making of Modern Sporting History, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland, 1979, pp 299–303

[21] Martin Painter and Richard Waterhouse, The Principal Club: a History of the Australian Jockey Club, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1992, pp 32–52; New South Wales, Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry Respecting the Legalising and Regulating the Use of the Totalisator in New South Wales, Government Printer, Sydney 1912, pp 157,175

[22] Margaret Williams, Australia on the Popular Stage, 1829–1929; an Historical Entertainment in Six Acts, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1983

[23] Richard Waterhouse, From Minstrel Show to Vaudeville: the Australian Popular Stage 1788–1914, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1990

[24] Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: a History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788, Longman, Melbourne, 1995, pp 101–14

[25] Richard Broome, Treasure in Earthen Vessels: Protestant Christianity in New South Wales Society, 1900–1914, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland, 1980, pp 141–49, 156–7

[26] My Ladies Journal, 1 March 1906; The New Idea, 6 January 1910

[27] Grace Karskens, 'The House on the Hill': the NSW Conservatorium and 'First Class Music', in Lenore Coltheart (ed), Significant Sites: History ands Public Works in New South Wales, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1989, pp 121–41

[28] Sydney Morning Herald, 31 July 1912

[29] Six O'Clock, 8 April 1916; Richard Waterhouse, Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: a History of Australian Popular Culture Since 1788, Melbourne, Longman, 1995, pp 159–63

[30] Rugby League News, 15 May 1920; Daily Telegraph, 29 April 1920; Sydney Morning Herald, 29 April, 8 May 1920

[31] Martin Painter and Richard Waterhouse, The Principal Club: a History of the Australian Jockey Club, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1992, pp 85–91

[32] Daily Guardian, 5 November 1927; Sydney Morning Herald, 4 July, 26 August 1927

[33] Inquiry into the Film Industry in New South Wales, Legislative Assembly, New South Wales, 1934, p 136; Sydney Morning Herald, 8 June 1929

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 October 1956, 19 November 1957

[35] Ian Heads, True Blue: The Story of the NSW Rugby League, Ironbark Press, Randwick, 1992, pp 250, 276; Sydney Morning Herald, 1 May 1959; Martin Painter and Richard Waterhouse, The Principal Club: a History of the Australian Jockey Club, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1992, p 128

[36] DN Jeans and MI Logan, 'A Reconnaissance Survey of Population Change in the Sydney Metropolitan Area 1955 to 1959', Australian Geographer, vol 8, September 1961, 119–31

[37] Phillip Sametz, Play On! 60 Years of Music-Making with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, ABC Books, Sydney, 1992, 101–186; Sydney Morning Herald, 8 December 1958

[38] Australian National Library, Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust Papers, Box 383, undated memo, 'Aims of the Trust'

[39] Richard Cashman and Anthony Hughes (eds), Staging the Olympics: The Event and its Impact, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1999

[40] Daily Telegraph, 15 December 1977; Sydney Morning Herald, 15 December 1977

[41] Sun Herald, 17 September 1967

[42] Business Review Weekly, 13 October 1989; Sydney Morning Herald, 23 September 1994

[43] Michael Sturma, 'When Rock and Roll Came to Australia', Journal of Popular Culture, vol 25, Spring 1992, pp 125, 131; TV Week, 28 February to 6 March 1959

[44] Megan Cronly, 'The Rise of the Surfing Subculture in Sydney, 1956–1966', University of Sydney BA thesis, 1983, pp 27–30

[45] Garry Wotherspoon, 'City of the Plain': History of a Gay Subculture, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, pp 109–38, 191, 209

.