The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

East Circular Quay

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

East Circular Quay

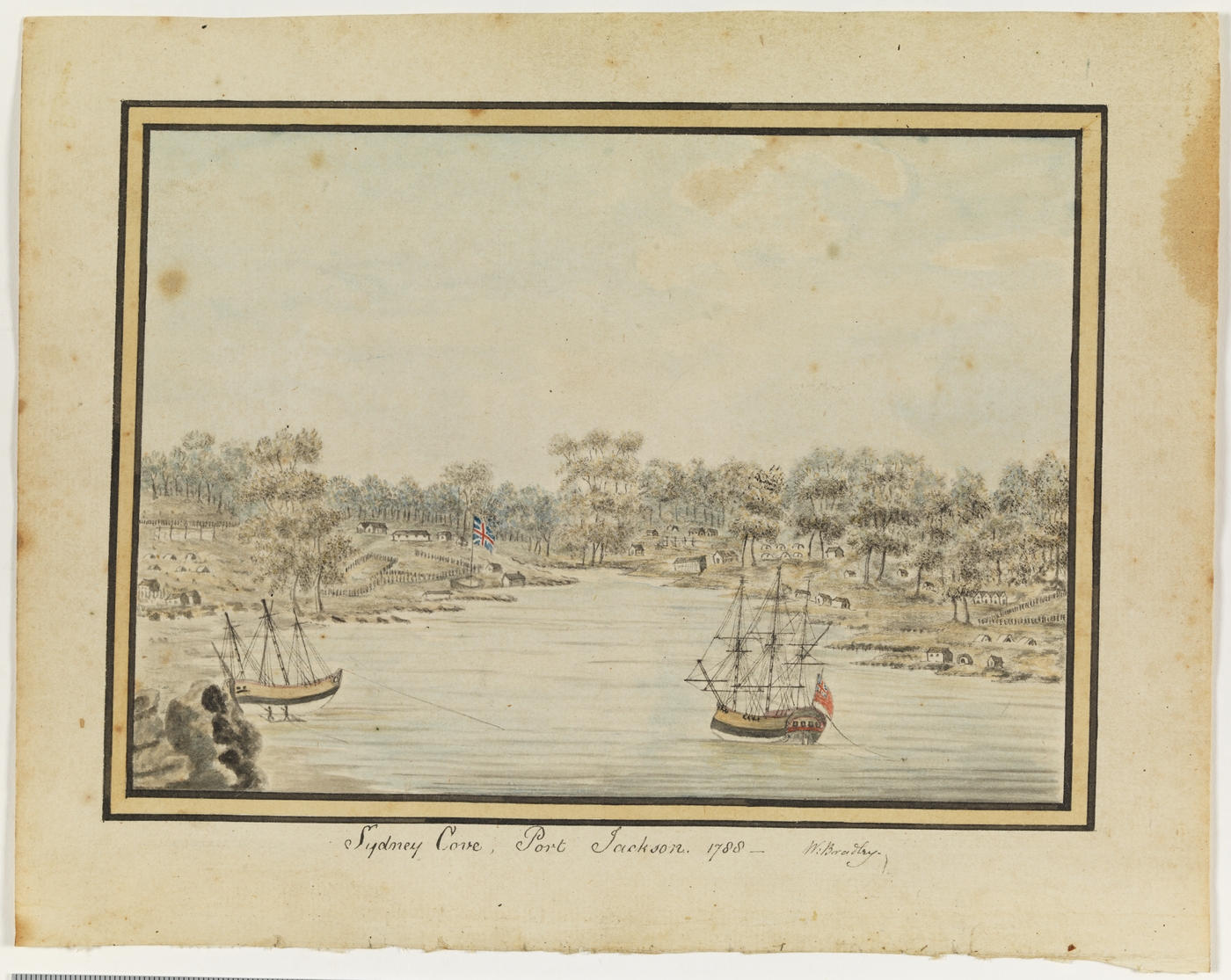

A [media]few days after the first landing by Europeans in Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788, Deputy Judge Advocate David Collins remarked that, amid the 'noise, clamour, and confusion' which reigned until 'order gradually prevailed' in the infant settlement:

A portable canvas house, brought over for the governor, was erected on the East side of [Sydney] ... cove ... where also a small body of convicts was put under tents. The detachment of marines was encamped at the head of the cove near the stream, and on the West side was placed the main body of the convicts ... The tents for the sick were placed on the West side, and it was observed with concern that their numbers were fast increasing...

On the eastern point of what was renamed Sydney Cove by the invading Europeans, Collins also observed:

The public stock, consisting of one bull, four cows, one bull-calf, one stallion, three mares, and three colts ... were landed ... where they remained until they had cropped the little pasturage it afforded; and were then removed to a spot at the head of the adjoining cove [Farm Cove], that was cleared for a small farm, intended to be placed under the direction of a person brought out by the governor.[1]

Thus, while animals grazed on the rocky outcrop, the tip of which was first known as 'Cattle' and later 'Bennelong Point', the initial decisions about the spatial arrangements for the new settlement were to have long-term meaning for the development of the area around Sydney Cove and its immediate environs. Convict, military and some civil establishments were centred on the western side of the cove, and land to the east was reserved for the governor's benefit and for administrative and legal establishments. Whatever reasons lay behind such segregation – better land to the east or the natural advantages for conducting ship maintenance and repair on the western side of Sydney Cove (later known as The Rocks) – this early official determination created

a primary division of functions as well as social classes; buildings to the west and open space to the east.[2]

Bennelong's point

Sloping and rocky, Sydney Cove's eastern point did not initially attract any European habitation. The first and one of the few dwellings erected on the eastern side of Sydney Cove was Bennelong's hut. [3]

[media]Severe shortages of salt led to a decision to allow John Boston to produce this necessary article at Sydney Cove. [4] Salt was still being produced on this spot in 1802.[5] But before the arrival of Governor Macquarie on 28 December 1809, further official dictates set directions for development between Farm Cove and Sydney Cove. During 1807, Governor William Bligh ordered James Meehan, Assistant Surveyor of Lands, to mark the following inscription across the Domain on a plan of Sydney that Meehan was preparing under Bligh's direction: 'Ground Absolutely necessary for use of Government House, but leases improperly granted on it.' [6]

Necessary commercial and other activities were tolerated along the eastern shore of Sydney Cove, though development was slow due, no doubt, to Bligh's clearly articulated policy. Most of this peninsula and Farm Cove remained the preserve of the Governor. Earlier, Phillip had given instructions that a ditch be marked out on paper to separate the vice-regal residence and grounds from the out-of-doors penitentiary and plebeian society: by October 1807, Meehan noted on his plan that this ditch had been 'now made by Governor Bligh'.

The Governor's demesne

After Bligh's deposition during the Rum Rebellion, his ditch was replaced by a stone wall. Keen on privacy and territorial delineation via the construction of walls and fences, Macquarie made sure that

the Government Domain, part of which Macquarie, and particularly his wife, visioned as the flowering garden into which it grew from their none-too-modest beginnings, was protected on the southern side, remote from the main gates and the guard, by ten feet of stone 'dividing it from the town across the neck of land between Sydney Cove and Woolloomooloo Bay'.[7]

Macquarie subsequently issued orders on 17 October 1812 informing the public that individuals would be 'severely punished, for Trespassing on the Government Domain', and that

no boat, except those belonging to the Government, are to be landed in Farm Cove, or on any other part of the shore bounding the Domain, except at Bennelong's Point, on pain of [the boat] being forfeited.[8]

Such injunctions notwithstanding, the stone wall, it would seem, worked against Macquarie's objectives. As MH Ellis has noted,

it was through this obstacle that inhabitants chose to enter the park, which provided a convenient refuge 'for persons going thither for vicious and disorderly purposes ... [or] for most indecent improper purposes'.[9]

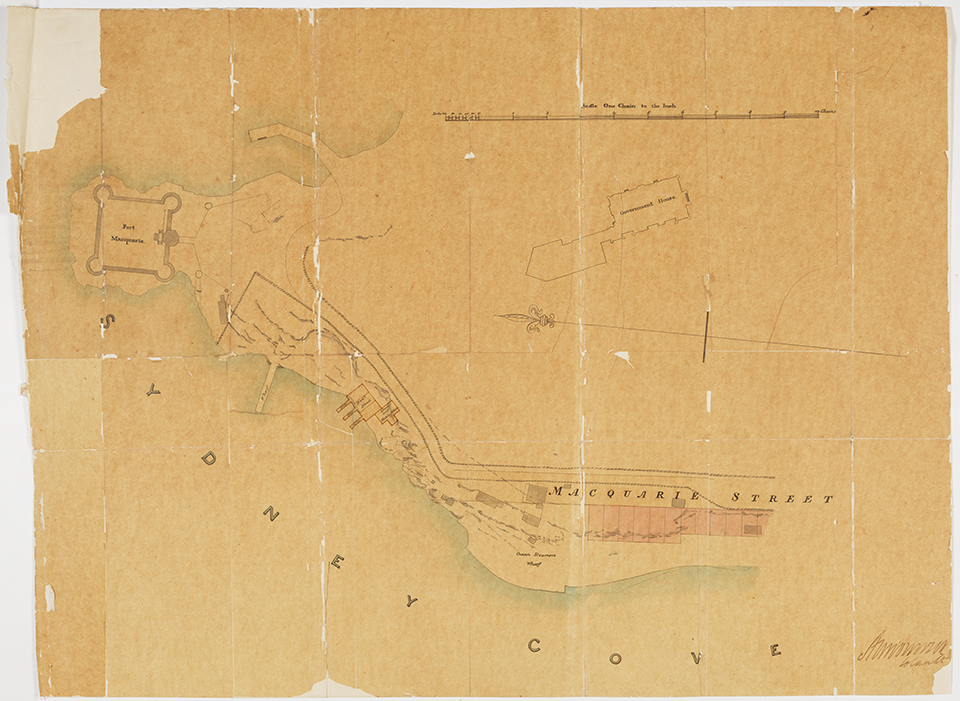

[media]A 'Plan of the Governor's Demesne', drawn in 1816 by C Cartwright, indicates pleasure grounds, gardens and parklands, carriage drives and various plantings, some exotic, stretching from the Government House to Bennelong Point and thence around to Farm Cove. (The Governor's 'Landing Place' was also located near the western tip of Bennelong Point.) Between 1813 and 1816, plans originated by Elizabeth Macquarie, Lachlan Macquarie's wife, for a drive from the thoroughfare around Bennelong Point to Anson's (now Mrs Macquarie's) Point, were completed, along with some landscaping.

Plebeian or unsavoury elements, however, were not welcome and fresh orders were posted listing punishments for interfering with or trespassing on the Government Domain. The orders, as published in the Sydney Gazette of 6 July 1816, were

not meant to extend to the prohibiting the respectable Class of Inhabitants from resorting to the Government Domain as heretofore, for innocent Recreation, during the Day Time; the Road some Time since constructed round Bennelong's Point furnishing easy Access in that Quarter, and the Gate and Style, at the East End of Bent Street, offering free admission in that Direction.[10]

Macquarie Street and Government House

At this time, Macquarie Street ended at Bent Street owing to the position of the government house. It was a number of years before the thoroughfare was extended north to Bennelong Point through this largely private landscape. And when Macquarie Street was pushed north, the new section became the 'wool store' end, the commercial working street, as opposed to the southern, premier precinct which became famous for its politicians, its would-be gentry, its parades and, finally, its professionals (first medical practitioners and then, in the twentieth century, lawyers). [11]

Though proclaimed on 6 October 1810 by Macquarie himself, the street which bears his name did not proceed north past Bent Street until the early 1840s when it was described on a plan as nothing more than a 'public footpath leading to Fort Macquarie', the foundation stone of which had been laid in December 1817. [12] Macquarie Street north did not become a reality until the mid-1850s and even then it was only partially formed, but the eventual extension of the street and the alienation of the land fronting East Circular Quay were predicated on relocating the governor's house, given the increasingly inadequate accommodation provided by the original vice-regal dwelling.

On his arrival in the colony in 1831, Governor Richard Bourke became quickly insistent that a 'new House must be built'. During the following year, Surveyor General Thomas Mitchell submitted a proposal to sell the land around the old government house, which faced Sydney Cove, for wharves and warehouses in order to help finance such a scheme. [13] Indeed, it was hoped that over £15,000 would be realised from the sale of these allotments, though this proved overly optimistic.[14] Plans for a new government house were prepared by the English architect Edward Blore in 1834 but it was not until 1837 – the year in which Bourke left the colony – that the foundations of the new castellated gothic Government House were laid. [15]

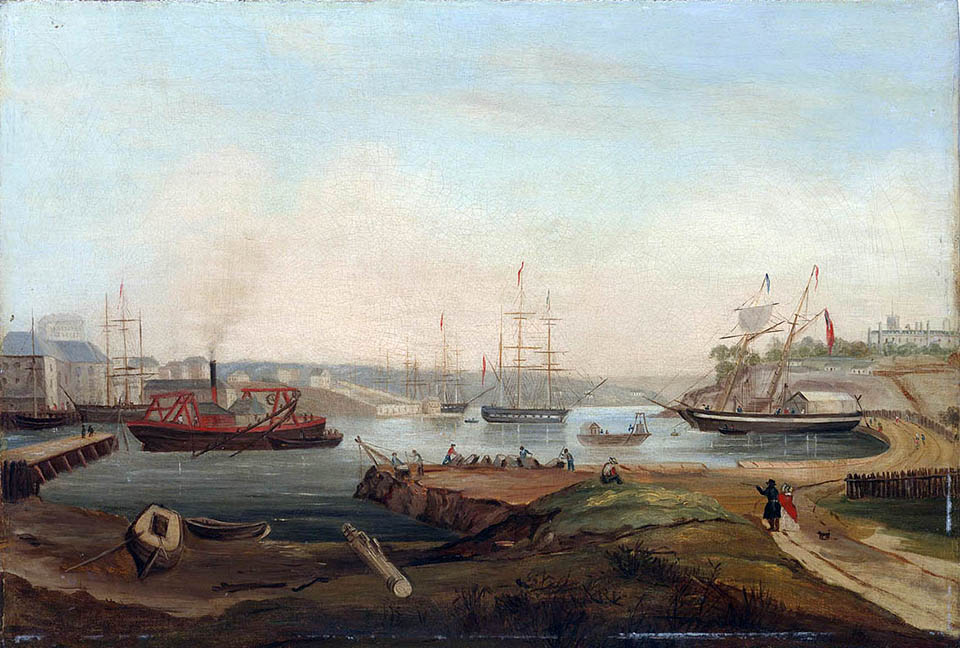

Semi-Circular Quay

[media]While the new government house was under construction, a 'Semi-Circular Quay' was built on the Tank Stream estuary's reclaimed tidal flats. Supervised by Colonial Engineer George Barney, work on the Semi-Circular Quay commenced in 1837. [16] Large numbers of convicts were used on this major work which was completed in 1844.[17] During at least part, and possibly all, of the construction of the Quay, a substantial portion of present day East Circular Quay was used as the 'Quarry and Works of the Circular Quay'. The name Semi-Circular Quay remained in popular usage until the 1850s when, between 1854 and 1855, the gap in the semi-circle caused by the Tank Stream was closed. [18]

The improvement of port facilities at Sydney Cove – including the provision of wharves, the regularisation of the shoreline for which sandstone was quarried at the tip of Bennelong Point and the construction of a lengthy berth and a road on the eastern side – did not necessarily imply other development around East Circular Quay or Bennelong Point. Economic depression between 1841 and 1844, sparked by a major reduction of British demand for wool and a decline in investment in the wool industry, meant that capitalists were not readily attracted to the allotments which became available on the eastern side of Sydney Cove.

[media]The onset of the gold rushes, too, undoubtedly adversely affected the saleability of these 28 allotments, few of which had been purchased by the mid-1850s. State provision of infrastructure and the opening up of the public land on the eastern side of Sydney Cove to alienation, however, tied the development of East Circular Quay and Bennelong Point to the subsequent boom in the wool trade and thus to the dynamic of colonial capital accumulation. [19]

The wool stores

[media]Wool stores and warehouses began to be constructed east of the Tank Stream from around the mid-1860s. Mort & Co's, completed in 1869 at a cost of £12,000, [20] was the most conspicuous. But it was not until the wool boom years of the 1860s that businessmen began to build wool stores, and other facilities, along East Circular Quay. By 1861, George Talbot had purchased two allotments where he built wool stores. After some wheeling and dealing these were erected on either side of a passage where the Moore Steps were constructed in 1868. [21] Moore Steps were named after Charles Moore, Mayor of Sydney between 1867 and 1869. A few other stores and bonds were built along Macquarie Street in the 1860s. But more substantial development was yet to come.

From the second half of the 1870s and throughout the 1880s, the wool industry underwent a relatively even period of growth. It was during this general period that Sydney began to rival Melbourne and Geelong in Victoria as the most important colonial centre in the marketing and handling of wool. By the close of the 1880s, these centres were 'offering a serious competitive threat to London'.[22] Thus, for 1880, the Sands Directory lists Flood & Co's Blackwall Stores at 1–11 Macquarie Street; Talbot & Co's stores at number 13; Moore Steps; then Talbot & Co again at number 15; Mason Brother stores at 15a; Cooper & O'Grady's 'The New Bond' at 17 Macquarie Street; P McMahon's bonded store at 19-21; and Marsden & Son's stores at 23-25.

By 1890, other prominent names connected with the wool industry – such as Pitt, Son & Badgery, Dalgety & Co and Hill, Clark & Co – had wool stores at East Circular Quay. Expansion in trade, however, stimulated the construction of major wool stores on the Pyrmont-Ultimo peninsula from the early 1880s – the first, built in 1883, was Goldsbrough Mort's gigantic wool store. These had various situational advantages, such as the Darling Harbour goods railway line. The shift of commercial focus from Sydney Cove to Darling Harbour and the Pyrmont-Ultimo peninsula towards the end of the nineteenth century may, in the longer term, have taken pressure off East Circular Quay for redevelopment.

Twentieth century redevelopment

The nineteenth-century wool and bond stores along Macquarie Street north dominated the local landscape from the 1860s until after World War II. It has been noted that the immediate post-World War II period

was an era in which the old imperially orientated, isolated Australia, dominated by the rural economy, gave way to the new urban, industrial society and a multicultural population. [23]

The demolition of the wool and bond stores, which commenced in the 1950s, was a dramatic symbol and manifestation of this transition in Australian society. They made way for Unilever House (designed by Stephenson and Turner) – the first 'modern' office block to be built on the site of the wool and bond stores between 1956 and 1957 – and ICI House (Bates, Smart and McCutcheon) – which officially opened on 31 October 1957. [24]

Later, after the lifting of the building height limit of 150 feet (45.7 metres) in 1957, taller structures rose on the site of the wool and bond stores, included the AMP Building (1962), Gold Fields House (1966) and Harry Seidler's Lend Lease House (1971). [25] These structures were monuments to the contemporary and unqualified commitment to 'progress' and development in the context of Australia's second long economic boom. [26]

Other major changes had also taken place around the Quay since the turn of the century. Sydney Cove's function was clearly changing by Federation. This had been expected by experts since the 1880s. The area was becoming a focus for commuter traffic on both ferries and trams, as well as for overseas liners. [27] Fort Macquarie, situated where the Tarpeian Rock and Bennelong's hut once existed, was demolished in 1902 to make way for a 'red brick tram-shed with crenellated tower' [28] which continued to be known as Fort Macquarie until it, in turn, was demolished in 1959 to make way for the construction of the Opera House which was opened in 1973. [29] From this time, the Quay took on a new status.

Between 1903 and 1913, the Sydney Harbour Trust was also responsible for remodelling the Quay. The Trust was established as a direct result of the outbreak of bubonic plague in Sydney in January 1900; it replaced the old pontoons around the Quay with two-storey gabled and tiled buildings. Despite some grandiose proposals which were suggested during 1908 Royal Commission into Sydney's Improvement, the Quay was to be increasingly disfigured by various intrusive developments.

While providing interesting viewing for many of Sydney's inner city unemployed during the 1930s depression, the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1925–1932) [30] was to overshadow and in many ways dwarf Circular Quay. Circular Quay railway station was planned in 1915. Work started in 1936 but it ground to a halt during World War II. It was eventually opened in 1956. [31] In that year, work began in the inner Domain on the Cahill Expressway.[32] Opened in March 1962, this monumental and unsightly conglomeration of steel and concrete provided the ultimate affront to Sydney's premier waterfront.

Since 1980, various developments and development proposals have been centred on East Circular Quay. These including Harry Seidler's 1983 design for the redevelopment of the precinct – the 'Gateway' proposal commissioned by Lend Lease – which did not proceed 'partly due to concern about its market acceptance'. [33] In February 1989, at the end of a property boom, Colonial Mutual Life (CML) finalised the purchase of five sites which were consolidated into the East Circular Quay development site. This process had commenced in 1971.

The Toaster

During October 1990, preliminary sketches of a proposed building for the site, designed by architect Dino Burattini, caused a great deal of controversy in Sydney's press. [34] The 'Bennelong Centre' was described by the Sydney Morning Herald as 'a wingless 747 about to hit the Opera House'. With an 11th-hour involvement from Prime Minister Paul Keating, a deal was struck to lower the height of the proposed buildings, which involved a swapping of the air-space rights above the site and improved the look of the site. This trade-off guaranteed public access to the private buildings and sent architect Andrew Andersons back to the drawing board to design Keating's vision for an imposing colonnade that 'touched the ground heavily', leaving us with the buildings that infamously became known as 'The Toaster'.

Other proposals prompted public outcries. One involved the City of Sydney Council selling the roadway adjacent to the site to CML to facilitate a lower, wider building and, as cynics noted, reduce CML's already significant financial loss. An Ideas Quest was established at the end of 1991. A special task force ultimately selected Andrew Andersons as the architect at the end of 1992. The development took on an even greater significance when, in March 1993, Sydney won the bid for the 2000 Olympic Games.

Controversy, however, continued over East Circular Quay throughout the 1990s. But today, with its indoor-outdoor restaurants and boutiques, and broad walkways around to the Opera House, the colonnaded 'Toaster' has become an accepted part of the Sydney scene.

Notes

[1] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, vol 1, (first published 1798), AH and AW Reed, Sydney 1975, pp 5–6

[2] KW Robinson, quoted in Norman Edwards, 'The Genesis of the Sydney Central Business District 1788–1856', in Max Kelly (ed), Nineteenth Century Sydney: Essays in Urban History, Sydney University Press in association with the Sydney History Group, Sydney 1978, p 38

[3] Joan Lawrence, Sydney from Circular Quay, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1987, p 29

[4] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, vol 1, (first published 1798), AH and AW Reed, Sydney 1975, p 355

[5] 'Plan of the Town of Sydney...September 1802', in Max Kelly and Ruth Crocker, Sydney Takes Shape, Doak Press, Sydney, 1978, p10

[6] Max Kelly and Ruth Crocker, Sydney Takes Shape, Doak Press, Sydney, 1978, p 12; Peter Spearritt, 'Circular Quay East, between Sydney Cove and Farm Cove: Its history and Significance', typescript, April 1989, p 2

[7] MH Ellis, Lachlan Macquarie: His Life Adventures and Times, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1978, p 341

[8] Quoted in Lionel Gilbert, The Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney: A History 1816–1985, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1986, p 19

[9] MH Ellis, Lachlan Macquarie: His Life Adventures and Times, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1978, p 341

[10] Quoted in Lionel Gilbert, The Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney: A History 1816–1985, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1986, pp 24–5

[11] Max Kelly, 'History Report' in Public Works Department, 'Macquarie Street: A Report on the potential improvements...', December 1983, vol 2

[12] Frank Clune, The Saga of Sydney, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1961, p 32

[13] Despatch from Gov NSW, Enclosures 1832–35, pp 1182–3, 1185, State Library of NSW, Mitchell Library manuscripts A1267–13

[14] Bourke to Boderick, Historical Records of Australia, series 1, vol 15, 2 November 1832, p 97

[15] James Maclehose, Picture of Sydney and Strangers' Guide in NSW for 1839, facsimile edition, John Ferguson, Sydney, 1977, pp 116–7

[16] Ralph Sutton, 'George Barney re (1792–1862), First Colonial Engineer', The Engineering Conference 1984: Conference Papers, Institution of Engineers, Australia, 1984, pp 13–17. http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=610769572085703;res=IELENG, accessed 21 August 2008

[17] Frank Clune, The Saga of Sydney, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1961, p 122.

[18] P Spearritt and L Martin, 'How it has happened', in Quay Visions, CAA/RAIA, North Sydney NSW, 1983, p 9

[19] Alan Barnard, The Australian Wool Market 1840–1900, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1958, pp 9, 10, 19–20, 147–9; S Wadham, R Kent Wilson and Joyce Wood, Land Utilization in Australia, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1957, pp 14–16, 119ff

[20] Emery Balint et al, Warehouses and Woolstores of Victorian Sydney, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1982, p 23

[21] Sands Directory 1861

[22] Alan Barnard, The Australian Wool Market 1840–1900, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1958, pp 147–8

[23] Stephen Alomes et al, 'The social context of postwar conservatism', in Ann Curthoys and John Merritt (eds), Australia's First Cold War 1945–1953, George Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1984, p 1

[24] Frank Clune, The Saga of Sydney, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1961, p 124, 126; Andrew Andersons, 'Macquarie Street: Sydney's Premier Street from 1810 to the Bicentenary', in P Weber (ed), The Design of Sydney, Law Book Company, Sydney, 1988, p 163

[25] Andrew Andersons, 'Macquarie Street: Sydney's Premier Street from 1810 to the Bicentenary', in P Weber (ed), The Design of Sydney, Law Book Company, Sydney, 1988, p 163–164

[26] Paul Ashton, The Accidental City: Planning Sydney Since 1788, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1993

[27] Alan Roberts, 'Planning Sydney's Transport 1875–1900', in Max Kelly (ed), Nineteenth Century Sydney: Essays in Urban History, Sydney University Press in association with the Sydney History Group, Sydney, 1978, p 29

[28] Frank Clune, The Saga of Sydney, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1961, p 32; CP Dolan, 'Fort Macquarie: Old Harbour Defences', in The Navy and Air Force Journal, 1 March 1935, pp 12–13

[29] JM Freeland, Architecture in Australia, Penguin, Ringwood VIC, 1974, pp 290–3; Michael Baume, The Sydney Opera House Affair, Nelson, Melbourne, 1967

[30] Peter Spearritt, The Sydney Harbour Bridge: A Life, George Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1982

[31] Garry Wotherspoon, Sydney's Transport: Studies in Urban History, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney 1983, pp 21–22; P Spearritt and L Martin, 'How it has happened', in Quay Visions, CAA/RAIA, North Sydney 1983, p 9

[32] Paul Ashton, '"An Architectural Monstrosity"?: The Cahill Expressway and Town Planning', in Martin Grotty and David Andrew Roberts (eds), The Great Mistakes of Australian History, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2006, pp 93-107

[33] Andrew Andersons, 'Macquarie Street: Sydney's Premier Street from 1810 to the Bicentenary', in P Weber (ed), The Design of Sydney, Law Book Company, Sydney, 1988, p 164

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 24 October 1990, p 8

.