The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Islands of Sydney Harbour

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Islands of Sydney Harbour

[media]Islands are special places. Their use and identity often reflects their separation from a mainland. Typically they are places of isolation, exile, security and defence, recreation and, sometimes, neutrality.

Sydney Harbour once had 14 islands. These were outcrops and the peaks of steep hills left uncovered as the sea level rose, between 10,000 and 6,000 years ago, flooding an ancient river valley and forming the harbour that exists today.

Aboriginal islands

Aboriginal people lived in and around that valley as the water slowly inundated the escarpments. They named their islands, possibly many times, in the 6,000 years that passed before Europeans arrived in 1788. The early colonial record suggests that the islands were called Boambilly (Shark Island), Billong-olola/Be-lang-le-wool (Clark Island), Ba-ing-hoe/Booroowang (Garden Island), Mat-te-wan-ye (Pinchgut/Fort Denison), Me-mel/Milmil (Goat Island), Wa-rea-mah (Cockatoo Island), Ar-ra-re-agon (Snapper Island) and Gong-ul (Spectacle Island). [1]

There were five other islands closer to the shore. The names for these have not survived in the written history of the waterway.

Neither is it clear what precise use Aboriginal people made of the islands, beyond exploiting access to fishing and shellfish. There is only one defined shell midden on Me-Mel, which contains the remains of Sydney cockle and hairy mussel. Early colonial lime burners exploiting the shell piles to manufacture lime for mortar may have depleted other sites. Nothing remains to be found on Wa-rea-mah/Cockatoo Island because it has been so extensively changed, though it is thought that it, as the biggest of the harbour islands, was a meeting place and that the two mid-stream islands, Boambilly (Shark Island) and Billong-olola/Be-lang-le-wool (Clark Island), were shared places. [2]

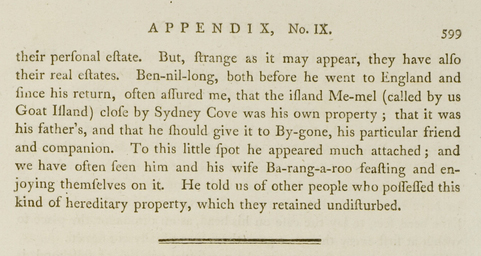

Bennelong[media] told the British that Me-mel/Goat Island 'was his own property', given to him by his father. For David Collins, who recorded this and many other aspects of Aboriginal social structure in the years immediately following colonisation, Bennelong's claim seemed to be evidence of Indigenous 'real estate'. There were others 'who possessed this kind of hereditary property' but Collins did not record their names and the places they owned. Possibly, the title to which Bennelong referred was not analogous to European ideas of private property.

The Englishman also noted both that Bennelong and his wife Barangaroo frequented the island to feast and 'enjoy themselves'. [3] Me-Mel lay off the far eastern end of the land of Bennelong's people, the Wangal. It is probable that the three other islands that sat much closer to their shore – the places that would be called Darling, Glebe and Rodd islands – were also regarded as Wangal land. Similarly, Berry Island on the north side was so close to the territory of the Gameraigal people that it was part of their land. Those who used the island carved a large image of a fish in the rock and used the sandstone to sharpen axes or spears over many years.

British occupation

The first island occupied by the British was the small outcrop off Bennelong Point, originally called Cattle Point by the newcomers and, then, Bennelong Island. The first name was utilitarian and reflected the use made of the place to land and confine livestock as Governor Phillip, his men and wards occupied the adjacent land around Warrane or Sydney Cove. The second name for the place derived from the residency of Bennelong himself at the point, in a house provided by Governor Phillip. Just as this was the first island trodden by British boots so it was the first to be joined to the mainland. That occurred around 1817 when the point was flattened and made ready for a fort. The place was renamed yet again, as Fort Macquarie, and all signs that it had once been an island were gone.

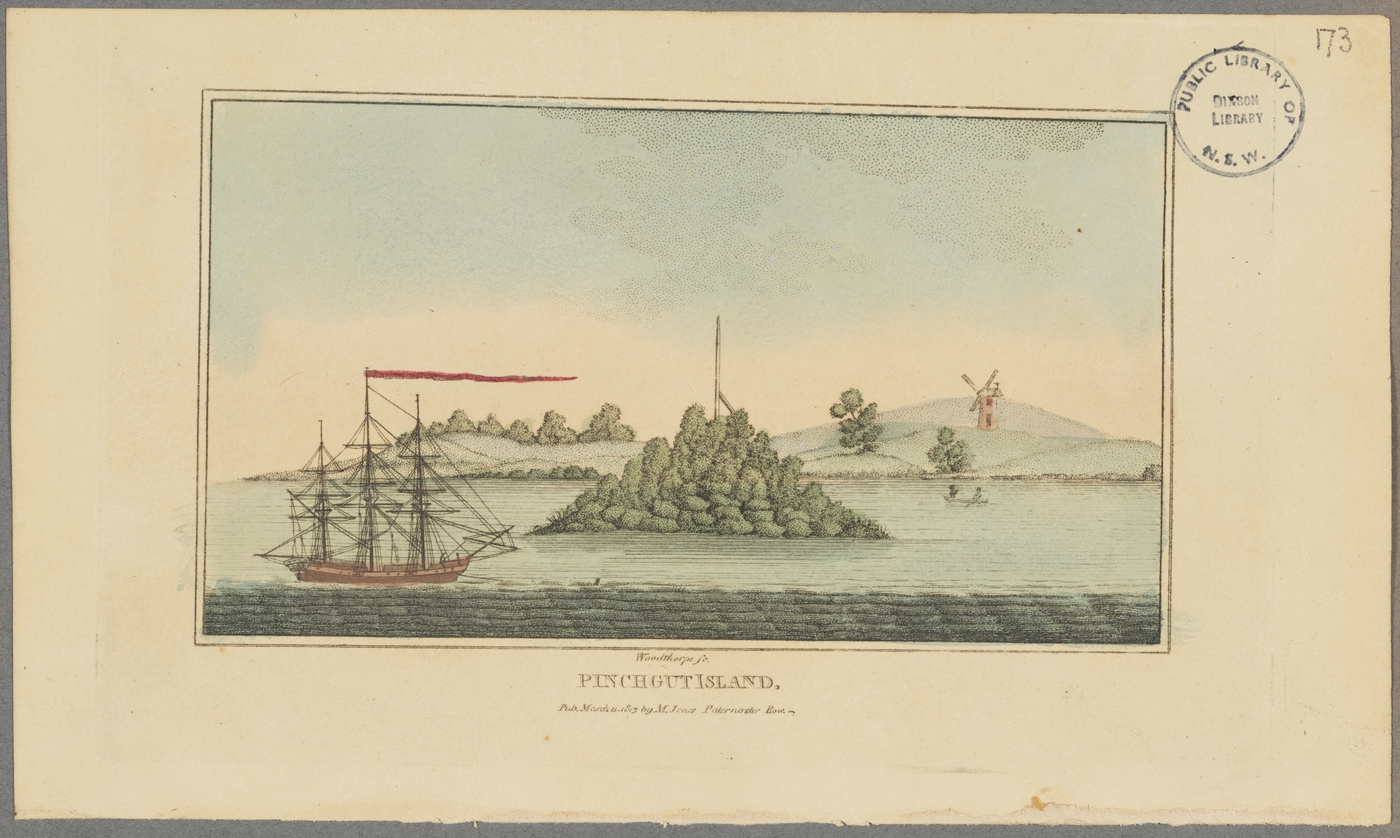

[media]In 1788, having corralled their cattle, Phillip and his command faced the problem of consolidating existing stores and procuring further food. Such was the scarcity and uncertainty that theft of food was punished severely. In February an example was made of a convict found guilty of stealing another's biscuit. Thomas Hill was sentenced to a week's 'confinement' with only bread and water on the 'small rocky island near the entrance of the cove'. That place was named simply Rock Island, then Pinchgut – a reference either to the starvation rations endured by its exiles or to the island's proximity to mainland and cove; a 'pinch' is a nautical term for such a narrow passage. In 1796 the murderer Francis Morgan was executed and his body gibbeted on the island as an exemplary spectacle to all who passed. [4]

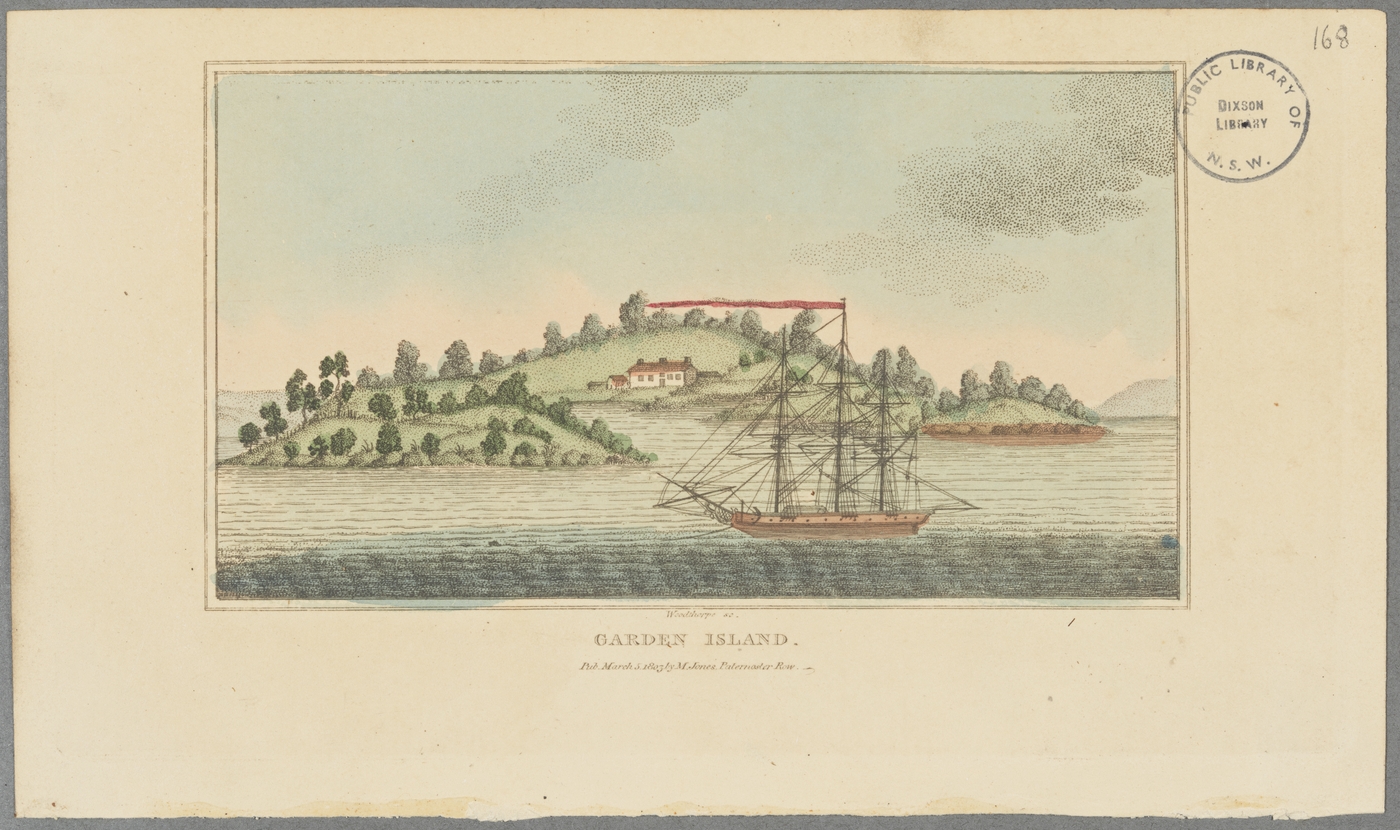

[media]The newcomers needed to grow food. Some of the sites chosen were allocated to ships of the First Fleet. Captain John Hunter of the Sirius chose Ba-ing-hoe or Booroowang, a short distance to the east of Sydney Cove, and again utility determined nomenclature so that place became Garden Island. Possibly security informed the choice of the island because it had no supply of water, so irrigating the crops entailed the added difficulty of carting buckets or barrels of water from the mainland. In that first year, after a successful harvest, three of the early gardeners carved and dated their initials, 'FM', 'IR' and 'WB', on the island's sandstone. The following year the place also became a site of incarceration when the convict escapee John 'Black' Caesar was put to work there among the onions and potatoes.

Lieutenant Ralph Clark appears to have packed for his First Fleet voyage with the intention of farming; shortly after arriving in the harbour he wrote back to his 'beloved Alicia' in England describing the hot summer and expressing the hope that his 'two hens and one pigg' would 'multiply fast'. In November the following year, Clark was given permission to plant out corn, onions and potatoes on Billong-olola, the small outcrop just east of Garden Island. There, among scribbly gum and banksia, he established a garden and, in doing so, gave his name to that island. But though it was separated from the southern shore by some 350 metres of water, Clark's small farm was not secure from theft. His plants were plundered at least twice and the Lieutenant abandoned his gardens.

Sandstone, gunpowder and grain

[media]It is not clear whether Clark's chickens multiplied, but the goats that others brought certainly did. Over the following decade, Me-mel became known as Goat Island – possibly because it was used to quarantine the meddlesome animals, or maybe because it resembled a goat resting. The British did not officially use it until 1831, when the quality of its sandstone and the availability of second-offending convicts thought to be in need of the lesson of 'hard labour' led to the establishment of quarries where building blocks were cut. Shortly after, the colonial administration decided to build gunpowder magazines on the island so that the explosive might be kept a safe distance from the town. [media]The convicts laboured to cut stone and then construct buildings from the blocks, while living on a hulk moored offshore. Later, when their numbers grew to 200, they lived in wheeled dormitory boxes on the island. The structures they left behind stood apart from Sydney town, which grew and constantly recreated itself, so that 150 years later Goat Island's buildings were appreciated as among the finest examples of early colonial architecture – survivors from a period when a town of stone grew upon the rock that gave it shape. In 1848 it was suggested that powder from the overfull powder magazine be moved to nearby Spectacle Island but this did not happen until a magazine was built there in 1865. Such was the busyness of the harbour by 1885 that concerns about a catastrophic explosion on Goat Island led to the removal of the powder to land bought for the purpose on an early colonial estate called Newington some 15 kilometres west up the Parramatta River.

In 1837 a water police station was established on Goat Island to take advantage of its location at the mouth of Darling Harbour and in the middle of the western harbour, which was becoming the busiest end of the waterway. This prime vantage point is a clue to the meaning of the island's Aboriginal name Me-Mel – 'eye'. The police shared the place with those who safeguarded the magazine for the next 20 years.

In 1839 convicts, some of them from the congested prison on Norfolk Island off the New South Wales coast, were incarcerated on War-ea-mah or Cockatoo Island; so named because of the flocks of noisy parrots that once perched in its sinewy red angophoras. The construction of secure storage facilities began again – this time for grain. Giant silos were dug out of the rock itself. The newly arrived military engineer, Captain George Barney, supervised this project, and the later stages of the Goat Island magazine construction. His ability, and his immediate affinity with the sandstone that was Sydney's bedrock, delivered other transformative works – the construction of Fort Denison, the Argyle Cut and Circular Quay. Barney, and the governor who ordered the works, saw the massive silos as a means of ensuring what, in a future century, would be called 'food security'. They would allow the government to take advantage of oversupply and low prices to stock up with grain for times of shortage.

But times were changing in other more fundamental ways. Transportation to New South Wales ended in 1840 and the following year the British government instructed Governor Gipps to allow the operation of a free market in produce prices. The grain bank that had been built at Cockatoo was an impediment to market forces and use of the silos was discontinued. [5]

Barney had also designed the barracks for the men who worked the stone on Cockatoo. The quarters held 200 and were later enlarged to accommodate 400 when the Norfolk Island penitentiary was closed altogether in 1855. The stone quarried on Cockatoo Island was used to build a town that was now more mercantile port than convict prison. For those both incarcerated and working on Cockatoo Island, it must have seemed like a case of 'out of sight, out of mind'. Supplies and rations were often delayed and punishment was brutal. Cockatoo Island served as a penitentiary for men until 1869 when the hard and often abused prisoners were transferred to Darlinghurst Gaol.

The island's role as a place of 'reform' continued afterwards when 'wayward', often hapless girls were sent there to the Industrial School and Reformatory for Girls, opened in 1871. Similarly unfortunate boys, who were housed in an old clipper ship called the Vernon, upon which they were taught trades and practical skills that, it was hoped, might turn them into sailors, joined them in that year.

Defensive islands

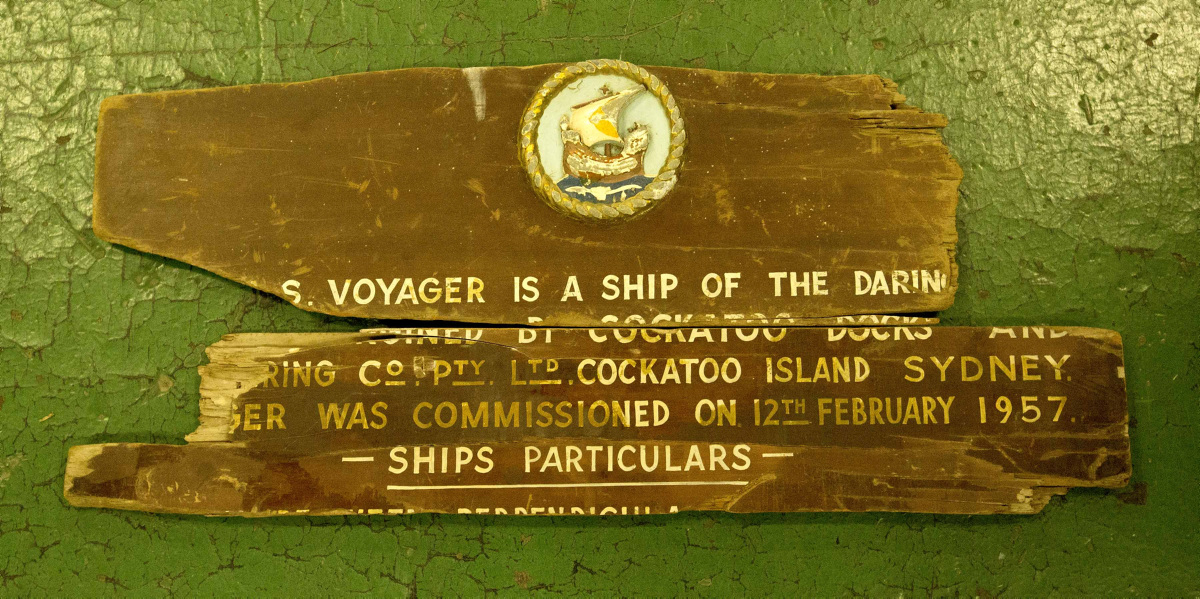

Back in 1846, Governor Gipps had wanted a dry dock built on Cockatoo Island, to service vessels of the Royal Navy's East India Station, which then were still only visitors to the harbour. Nervous Sydneysiders, and there were many of them, would have much preferred a permanent naval presence to deflect potential Russian or French aggression. The Fitzroy Dock was begun on Cockatoo Island in 1847 but not completed until 1857, by which time the Australian Division of the East India Station had been formed and British men o' war were routinely anchored in the harbour. In the process, the high rocks on the southeast corner of Cockatoo were blown apart with explosive. The remodelling of the island would continue until it resembled a simple platform on which to build.

In the same year that the Fitzroy Dock was completed, Fort Denison became operational as a defence establishment. Its construction was a response to the same fears that prompted colonials to seek better naval protection, though its protracted completion from 1840 to 1857 was evidence of the lack of interest in peripheral defence in London. George Barney supervised much of the work and the result was a Martello tower, a design derived from Napoleon's highly effective circular defensive towers on Mortella Point in Corsica. In the course of construction, pyramidal Pinchgut was transformed, as Cockatoo would be, from rocky outcrop to platform. The work prompted what was possibly the first environmental protest in Sydney when radical Presbyterian minister Dr John Dunmore Lang decried the act of 'vandalism' that destroyed a 'natural ornament of the harbour' that so obviously was the artistic 'work of God'. [6]

The next year, 1858, the Royal Navy was given possession, but not control, of the whole of Garden Island, in time to house the Australia Station created in 1859. By then, however, New South Wales had also achieved responsible government and with that came the expectation on the part of the Admiralty that local funds would be contributed for colonial defence. Royal Navy vessels stationed at Garden Island assisted in the consolidation of British influence in the Pacific. But it was not until 1896 that full control of the island – nearly 40 years in the fitting out – was completely handed over to the Admiralty. The powder magazine on Spectacle Island had become the Royal Navy's armaments depot in 1883. In July 1913, the Commonwealth of Australia took over Garden Island for its Royal Australian Navy, which steamed into the harbour in October that year.

Industry and pleasure

Commerce had continued to have an impact upon the harbour islands to the west. Little Darling Island, off Pyrmont, was connected to the mainland in 1854 with the construction of one of the harbour's largest slipways for the Australasian Steam Navigation Company. Further to the west, a large parcel called Glebe Island, because it had been included in an early grant to the Anglican chaplain Richard Johnson, was joined to the mainland by a causeway so that stock could be driven across for slaughter in the newly constructed abattoir opened in 1860. That place would affect the quality of the air for kilometres around and pollute the water throughout the harbour as unwanted offal drifted back through the Heads after dumping at sea.

Two sides of Sydney Harbour were developing; an industrialised west typified by the abattoir and the boat yards, and a more salubrious eastern end. Garden Island marked the dividing line. It was to some extent an accidental division, because military resumptions along the eastern part of the north shore through the 1860s had preserved that land from development. The higher foreshores on the north side also made development more difficult. In keeping with the greener, more pleasant eastern waterway, both Shark and Clark Islands had become a popular picnic spots by the 1870s and both were declared public reserves in 1879. In the following decades they would be planted out with one of the distinctive horticultural symbols of Sydney's waterfront reserves, the Canary Island Palm.

As a concession to the residents of the west, little Rodd Island, tucked back beyond the abattoir and boatsheds, was also made a reserve in 1879. That decision ended the hopes of its namesake, Brent Rodd, of ever gaining freehold to the island that sat near his mainland 'manor' and extensive landholdings around Iron Cove, and from which he reputedly chased off wood cutters and lime burners who were mining the Aboriginal middens. Such were his expectations that Rodd built a family mausoleum on the island.

In the 1850s Rodd may have looked with some envy at the holdings of Alexander Berry on the north side. Berry's estate, inherited through marriage from his erstwhile business partner and brother-in-law Edward Wollstonecraft, ran to more than 200 hectares, which included plenty of foreshore and the outcrop that would be known as Berry Island. Sometimes joined to the mainland by a spit of sand, it was permanently linked after becoming a park in 1926. That declaration followed a 1906 deal in which state government bought back much of the Berry estate foreshore.

Vermin, disease and redevelopment

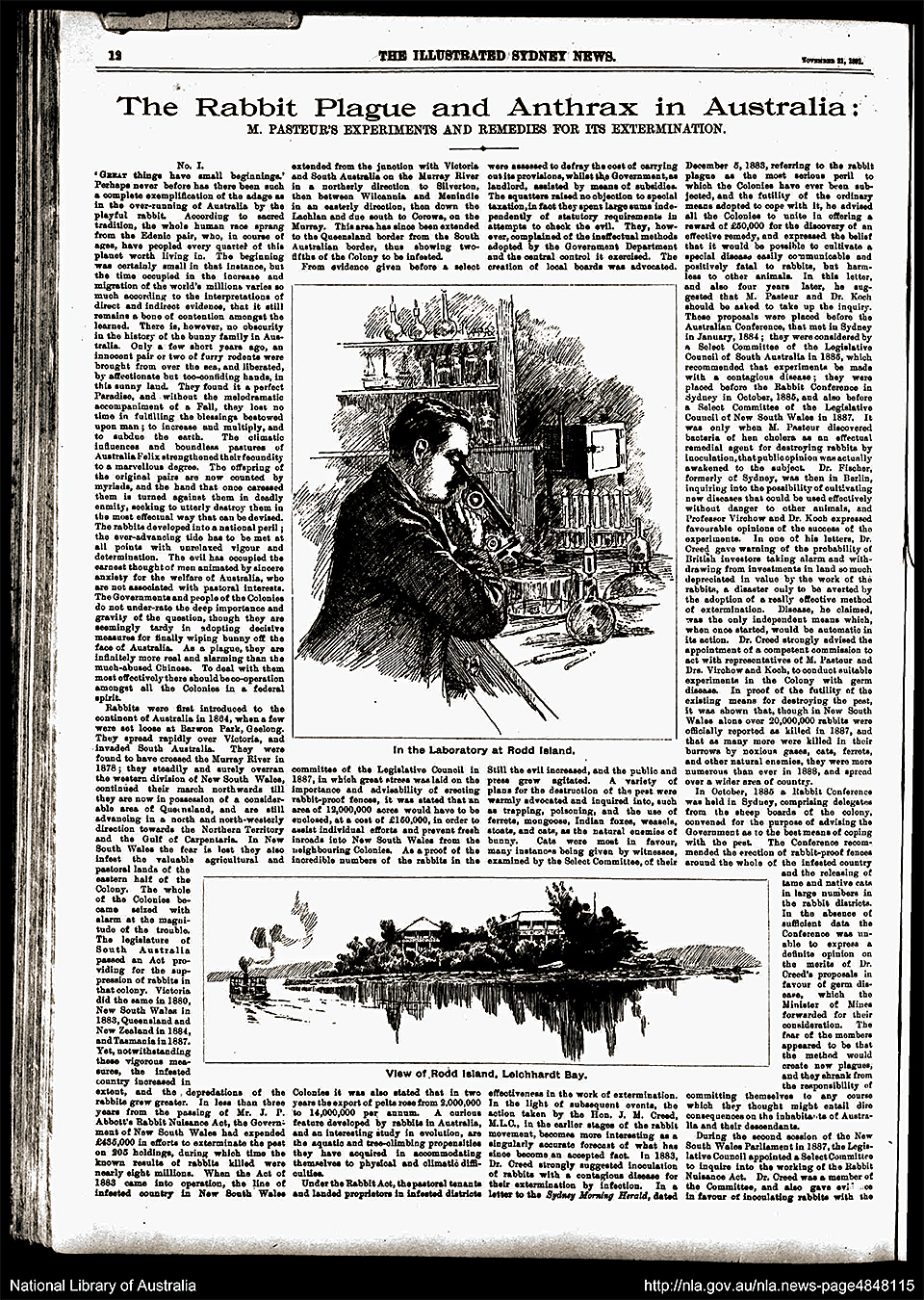

[media]The Rodd Island reservation was revoked in 1888 when a desperate colonial government decided to establish a laboratory there to explore biological controls for rabbits, which had reached plague proportions throughout New South Wales. A prize was offered to anyone who discovered a disease that would kill rabbits without endangering other animals. The renowned French microbiologist Louis Pasteur sent a team headed by his nephew Adrien Loir to participate and compete for the prize, and experiments were conducted on Rodd Island. However, the Commission convened to judge the results was unconvinced by Loir's findings. Pasteur was not awarded the prize and his representatives left 'greatly dissatisfied'. [7]

The laboratory complex remained in use until 1894 when the island was returned to the public as a reserve. The inevitable Canary Island Palms were planted and picnickers and bathers visited the place over the next 50 years. In the more permissive 1960s and 1970s boat-borne revellers, often intoxicated, held parties on and just off the island. This led to suggestions for the construction of a marina and restaurant complex which, in turn, prompted the formation of the 'Friends of Rodd Island' to protest against the development. The Friends were organised in the manner of many other resident action groups that formed in Sydney from the early 1970s to assert local control over development. In 1981 the island became part of the newly created Sydney Harbour National Park, managed by the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS). Their task included the conservation and interpretation of the buildings that dated back to the days of Loir's experiments, and the planting of endemic flora next to exotic palms.

The island inherited by the NPWS was, somewhat ironically given its history of experimentation, overrun with rats. The black and brown rodents from Europe and Asia had been among the first exotic animals brought to the harbour as a result of colonisation. In 1900, rats themselves delivered bubonic plague to the waterway. More than 100 people died within seven months. Another bacteriological laboratory was established, this time on Goat Island, which sat adjacent to the worst affected area of Darling Harbour and Millers Point.

The epidemic also prompted a dramatic reorganisation of harbour activities; one that involved foreshore resumptions, the demolition of old wharves and the building of new ones, including some at Darling Island which had long been joined to the mainland. The Sydney Harbour Trust was established to supervise the new modern waterway. From 1936 this body was called the Maritime Services Board (MSB). Goat Island became the home of the Trust/MSB fleet of tugs, dredges and fire floats which grew to number 170 vessels. From 1919, boatyards, slipways and wharves were built on the island to service the fleet. The island was also home to the families of dozens of Trust/MSB workers. Jessie Hickey, who grew up on Goat Island in the 1930s and 1940s, recalled a life that was both connected and disconnected from the city nearby:

Shopping was done at the Quay and milk came from Balmain. We had to put in a big order, probably once a month for groceries … There was nothing available on the island … We went swimming and fishing and made fish-traps (and crab-pots) out of wire netting. [8]

Naval islands at war and after

War came to the harbour as young Jessie swam and fished. The activity on Goat Island paled compared to that on Cockatoo and Garden islands. A second large graving dock, called the Sutherland Dock, had been completed on Cockatoo in 1890 and the island was given over to ship construction and repair through World War I and afterwards. Between 1940 and 1945, three Tribal class destroyers and two River class frigates were built and launched there, along with numerous smaller naval craft. War in the Pacific brought battle casualties: 15 United States Navy, 11 Royal Australian Navy and nine Royal Navy vessels were repaired on Cockatoo. [9]

In 1942 on Garden Island, writer and poet Nancy Keesing began her first job as an 18-year-old clerk in the Naval Accounts department. She remembered watching the work of the foreman moulder, Reg Mulligan:

With no apparent effort, every movement controlled and every movement beautiful, he could scoop the perfect shape of a casting – propeller, rod or wheel – from a box of heavy wet sand. [10]

In 1944, a graving dock was begun that could service an aircraft carrier and would dwarf those on Cockatoo. When the Captain Cook Dock was completed in 1945, Garden Island was an island no longer and Nancy Keesing and others 'could walk to Potts Point and buy a decent meal' when they worked overtime.

The war curtailed recreational boating east of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The 14-inch gun barrels from George V class battleships were stored for the Royal Navy on Clark Island. Over in the western harbour, the Americans made Glebe Island their own. Port improvements had erased any suggestion of this being an island. Giant wheat silos and a rail link to move the grain had replaced the old abattoir from 1918 and the transport connection and improved wharves proved ideal for supplying and staging thousands of American troops going to and from the fighting in the Pacific.

Snapper Island too was briefly taken over by the Americans in 1942 as a school for naval gunners. This small island had been ignored by the authorities for much of its previous history, remaining a place that boat-wise children and fishers scrambled over. The navy controlled the outcrop from 1913, when nearby Cockatoo and Garden islands were passed to the new Royal Australian Navy. From 1931 Snapper was a training depot for naval cadets. This coincided with the breaking up of Australia's most famous warship, the first HMAS Sydney. Snapper became home to an extraordinary array of objects, many of them from the Sydney, which together told much of the story of Australia's young navy. [media]Some of this was later transferred to Spectacle Island, which became home to the Naval Historical Collection in the 1960s. Objects from here, in turn, were used for the displays mounted at the Royal Australian Navy Heritage Centre on Garden Island, which opened in 2005.

Vessels still dock and resupply at Garden Island, which is part of the naval station HMAS Kuttabul, Fleet Base East of the Royal Australian Navy. However, the hammerhead crane towering over the dockyard is no longer used. For 40 years from 1951, the Garden Island crane was a twin to 'Titan', the giant hammerhead structure that had crowned Cockatoo Island since 1918. 'Titan' was towed away in 1992. The Garden Island crane became redundant four years later. In 2013 it was decided that the cost of retaining it as a heritage item was too great. When that structure is dismantled the harbour will have lost the last visible symbol of the working waterway on a skyline dominated by skyscrapers, the Opera House and the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Shipbuilding at Cockatoo Island continued for 20 years after the end of World War II. From 1965 to 1992, workers there serviced the Royal Australian Navy's Oberon class submarines stationed at nearby Neutral Bay. They did commercial work and constructed the combat support vessel HMAS Success, then the largest ship built in Australia. The launch of Success, however, presaged the end of shipbuilding in the harbour rather than its revitalisation. Economics and, indeed, the location of the island, militated against ongoing work. As John Jeremy, Cockatoo's last Chief Executive Office, later reflected:

an island in the middle of Sydney Harbour is a lousy place to put a dockyard... It introduced all kinds of restraints on material flow and handling … You wouldn't do it today. [11]

The dockyards and slips were closed in 1992.

Heritage and history

In 150 years of development Cockatoo Island grew from 12.9 hectares to 17.9 hectares. The closure of the working facilities there was the most dramatic indication of the transformation of Sydney Harbour from an industrial port to a place where service and cultural activities dominate. [12] In 2001 the newly formed Sydney Harbour Federation Trust took control of the island. Gradually, vast working interiors were given over to performances and art exhibitions. Campers now enjoy the ambience of a much quieter waterway along the island’s artificially created foreshore. The Navy still controls nearby Snapper and Spectacle islands. But all the other extant islands, Rodd, Goat, Fort Denison, Clark and Shark, are managed by the National Parks and Wildlife Service as part of the Sydney Harbour National Park, first gazetted in 1975.

In 2010 Cockatoo Island was included on the UNESCO World Heritage List because of the significance of its surviving convict structures. That recognition highlights the extent to which the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust and National Parks and Wildlife Service must balance the preservation and interpretation of natural and cultural history of Sydney's harbour islands with their ongoing, often changing, public use.

References

Simon Davies, The Islands of Sydney Harbour, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1984

TR Frame, The Garden Island, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1990

John Jeremy, Cockatoo Island: Sydney's Historic Dockyard, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998

Peter Oppenheim, The Fragile Forts: The Fixed Defences of Sydney Harbour, Department of Defence, Canberra, 2004

PR Stephenson and Brian Kennedy, The History and Description of Sydney Harbour, AH and AW Reed, Sydney, 1980

Notes

[1] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records, second edition, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 9–13

[2] Mary Shelley Clark and Jack Clark, The Islands of Sydney Harbour, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2000, p 177

[3] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales, vol 1, AH and AW Reed, Sydney, (1798) 1975, p 499

[4] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales, vol 1, AH and AW Reed, Sydney, (1798) 1975, p 7

[5] Mary Shelley Clark and Jack Clark, The Islands of Sydney Harbour, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2000, p 38

[6] John Dunmore Lang, An Historical and Statistical Account of New South Wales, vol 2, Longman, Brown Green and Longman, London, 1852, pp 153–154

[7] The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 May 1889

[8] Mary Shelley Clark and Jack Clark, The Islands of Sydney Harbour, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2000, pp 24–25.

[9] RG Parker, Cockatoo Island: A History, Nelson, West Melbourne, 1977, pp 76–77

[10] Nancy Keesing, Garden Island People, Wentworth Books, Sydney, 1975, p 61

[11] Interview with John Jeremy, Stories from Former Workers, Cockatoo Island website, Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, http://www.cockatooisland.gov.au/about/history-stories-from-former-workers.html, viewed 1 February 2014

[12] For an account of this general transformation see Ian Hoskins, Sydney Harbour: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2009

.