The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The National Trust

Building and Engineering, 24 November 1947 p40-41 via Trove

Building and Engineering, 24 November 1947 p40-41 via Trove

The Military Hospital, in 'The town of Sydney in New South Wales c1821', by Major James Taylor (courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW V1/ca.1821/5)

The Military Hospital, in 'The town of Sydney in New South Wales c1821', by Major James Taylor (courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW V1/ca.1821/5)

Mark Dunn is the Chair of the NSW Professional Historians Association, the Deputy Chair of the Heritage Council of NSW and a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of NSW. You can read more of his work on the Dictionary of Sydney here. Mark appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Mark!

Listen to the audio of Mark & Julia here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.Sydney through a novelist's eyes

Ruth Park, pre 1947, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (P1/Park, Ruth)

Ruth Park, pre 1947, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (P1/Park, Ruth)

One of Noela Young's iconic illustrations for the Muddle Headed Wombat books.

One of Noela Young's iconic illustrations for the Muddle Headed Wombat books.

Australian Women's Weekly, 21 Oct 1973 p15 via Trove

Australian Women's Weekly, 21 Oct 1973 p15 via Trove

The Satyr and Five Bells

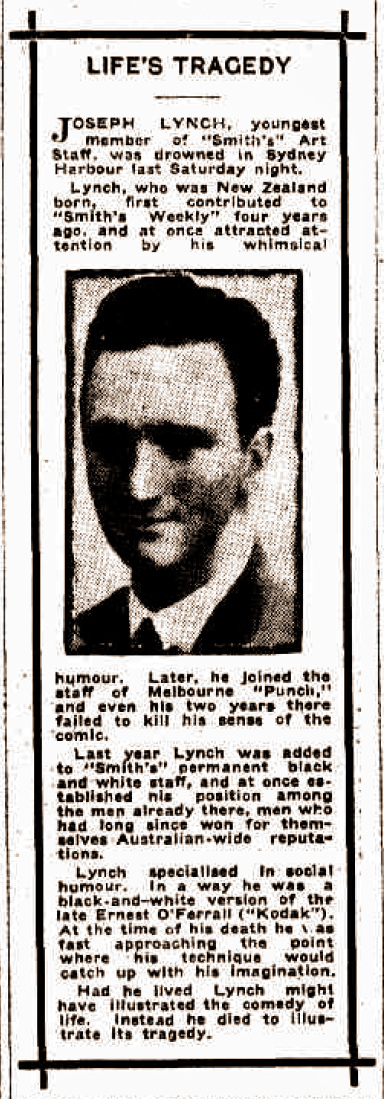

Life's Tragedy: announcement of Joe Lynch's death in Smith's Weekly, 21 May 1927, via Trove

Life's Tragedy: announcement of Joe Lynch's death in Smith's Weekly, 21 May 1927, via Trove

Listen to the audio of Minna and Tess on 2SER here

Deep and dissolving verticals of light Ferry the falls of moonshine down. Five bells Coldly rung out in a machine's voice. Night and water Pour to one rip of darkness, the Harbour floats In air, the Cross hangs upside-down in water.

from Five Bells, Kenneth Slessor, 1939

As you walk along the edge of the Royal Botanical Gardens near the Man O’War steps you might stumble upon The Satyr. A small bronze statue with big hairy goat legs and the torso of a man with a very cheeky smile on his face. Eyes half shut, he leans back on his podium like he’s just told a joke. Originally it was sculpted in plaster by Guy Lynch and exhibited in 1924 in the Young Australian Artists’ exhibition in the Anthony Hordern and Sons Fine Art Gallery. To get the correct proportions, Guy tied up a goat in his backyard and then got his brother Joe Lynch to model for the torso. Reviews of the work at the time veered between 'magnificent' and 'remarkable' to 'insolent, vicious and animal to the last degree'. Joe and Guy were fixtures of the 1920s bohemian scene in Sydney, carousing with artists and journalists. Joe worked at the popular newspaper Smith’s Weekly as a black and white cartoonist with colleagues like the poet Kenneth Slessor who later described Joe’s wild personality as prone to mad Irish humour and mad Irish rages, a ‘devout nihilist [who] frequently over a pint of Victoria Bitter said the only remedy to the world’s disease was to blow it up an start afresh’ (Daily Telegraph, 31 July 1967). Most Saturday nights they would all head to their friend George Finey’s apartment in Mosman to party. On Saturday, 14 May 1927, Joe finished work at Smith’s, put on his old overcoat and walked down to Circular Quay to meet the crew, including Guy. The harbour bridge was still being built and people would often gather at the pubs nearby to wait for the ferry to take them across to the other side. They got on the 7.45pm ferry, carrying drinks on board - Joe loading up his overcoat pockets with bottles of beer. Because there were not enough seats, Joe was leaning against the rail on the outside deck. Suddenly as they passed Fort Denison, he disappeared over the side and into the black water. His body was never recovered. For most Sydneysiders at the time, Joe’s drowning was unremarkable, but for Guy, things were never the same. He ‘went to pieces’ and took to pacing the harbour foreshore in front of the Royal Botanic Gardens, looking out to the water as if looking for his brother. The Satyr, Royal Botanic Gardens 2014, courtesy Lindsay Foyle

The Satyr, Royal Botanic Gardens 2014, courtesy Lindsay Foyle

Sydney’s Tank Stream

Listen to Mark and Julia on 2SER here

When the British arrived in the First Fleet, Arthur Phillip, the first Governor, used this stream to order his rambling camp. To the east he had a space cleared for the erection of a prefabricated, temporary house to serve as the Government House, with land close by set aside for his officials and administrators. On the west the military began to establish what would become their barracks and the convicts were left to set tents and later build their huts along the ridge in what became the Rocks. Phillip’s hastily thought-out camp plan, based around the stream set the foundation for the future city and is still discernible today. To the east of the stream, which essentially runs under Pitt Street, sit the State parliament, law courts, the hospital and other government functions, to the west the commercial city moved into the space left behind by the barracks (modern day Wynyard) and the convict town of the Rocks. Detail showing the Tank Stream from 'Plan of the town and suburbs of Sydney, August 1822', courtesy National Library of Australia (MAP F 107)

Detail showing the Tank Stream from 'Plan of the town and suburbs of Sydney, August 1822', courtesy National Library of Australia (MAP F 107)

Tank Stream 1842 by Frederick Garling, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 420)

Tank Stream 1842 by Frederick Garling, courtesy Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (ML 420)

Mark Dunn is the Chair of the NSW Professional Historians Association, the Deputy Chair of the Heritage Council of NSW and a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of NSW. You can read more of his work on the Dictionary of Sydney here. Mark appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Mark!

Listen to the audio of Mark & Julia here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast with Tess Connery on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.Judith Brett, Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage

Judith Brett, Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia Got Compulsory Voting

Judith Brett, Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia Got Compulsory Voting

Text Publishing, 2019, 208pp., ISBN: 9781925603842, p/bk. AUS$29.99

I don't normally do book reviews, but I've just recently finished From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage by Judith Brett, Emeritus Professor of Politics at La Trobe University, which ticks the boxes of being a new book about topics central to the theme of my website, The Tally Room, and it was an excellent read. There is a lot out there for a dedicated reader of Australian electoral history, but not much of it is written for a broader audience. I have learned a lot in particular from Peter Cochrane's Colonial Ambition, which focuses on the development of democratic institutions in New South Wales from the 1840s until the 1860s, and The Australian Electoral System by David Farrell and Ian McAllister, which covers the history of the Australian electoral system along with more contemporary content, in a format closer to that of a textbook. I also found Peter Brent's PhD 2008 thesis The rise of the returning officer : how colonial Australia developed advanced electoral institutions interesting in exploring how the structure of Australian electoral administration evolved. I'm sure there's a lot more in the political and historical journals yet to be read. So many of the topics in Brett's book weren't new to me, but they were told in a very engaging and interesting way, telling the story about the origins of each major development in Australia's voting system and giving more atmosphere to the motivations and actions of key players in these developments. The book's blurb focuses on compulsory voting, as does the subtitle. Compulsory voting is definitely an important theme that appears a number of times in the book, but this story isn't just about compulsory voting. It also covers a bunch of other distinctive Australian electoral innovations that don't have much to do with compulsory voting. The book covers:- the invention of the Australian ballot, including the provision of a standardised government-issued ballot paper and the provision of a private space to mark that ballot;

- the development of independent electoral administration including the role of William Boothby;

- the direct election of the Senate, as set down in the Constitution;

- the Franchise Act of 1902, which enfranchised women while disenfranchising Indigenous Australians and other people of colour;

- the first attempts to introduce preferential and proportional voting systems in 1902 and the subsequent adoption of these voting systems in 1919 and 1948;

- early unsuccessful attempts to introduce compulsory voting, the successful introduction of compulsory enrolment followed by the introduction of compulsory voting in 1924;

- voting on Saturdays;

- the rise of the Country Party in sync with the introduction of preferential voting in 1919, and how the introduction of proportional representation in the Senate helped encourage more minor parties;

Customs House

Custom House and Circular Quay 1845 by GE Peacock, courtesy Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG 35)

Custom House and Circular Quay 1845 by GE Peacock, courtesy Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG 35)

Contraband at Customs House, 11 July 1939, courtesy Mitchell Library & ACP Magazines Ltd, State Library of NSW (ON 388/Box 028/Item 143)

Contraband at Customs House, 11 July 1939, courtesy Mitchell Library & ACP Magazines Ltd, State Library of NSW (ON 388/Box 028/Item 143)

Sydney’s pissoirs & underground conveniences

Urinal Observatory Hill 1968, Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (CRS 34/2401/71 )

Urinal Observatory Hill 1968, Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (CRS 34/2401/71 )

Detail of architectural drawing of Wynyard Park underground convenience 1911, Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (CRS 569 0419)

Detail of architectural drawing of Wynyard Park underground convenience 1911, Courtesy City of Sydney Archives (CRS 569 0419)

Bunting, pickets and harpoons - electioneering Sydney style

Embroidered election banner for Wentworth and Bland, 1843-1849, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (LR 3a)

Embroidered election banner for Wentworth and Bland, 1843-1849, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (LR 3a)

William Hustler's poetic plea to the electorate, The Australian, 19 May 1843, p4 via Trove

William Hustler's poetic plea to the electorate, The Australian, 19 May 1843, p4 via Trove

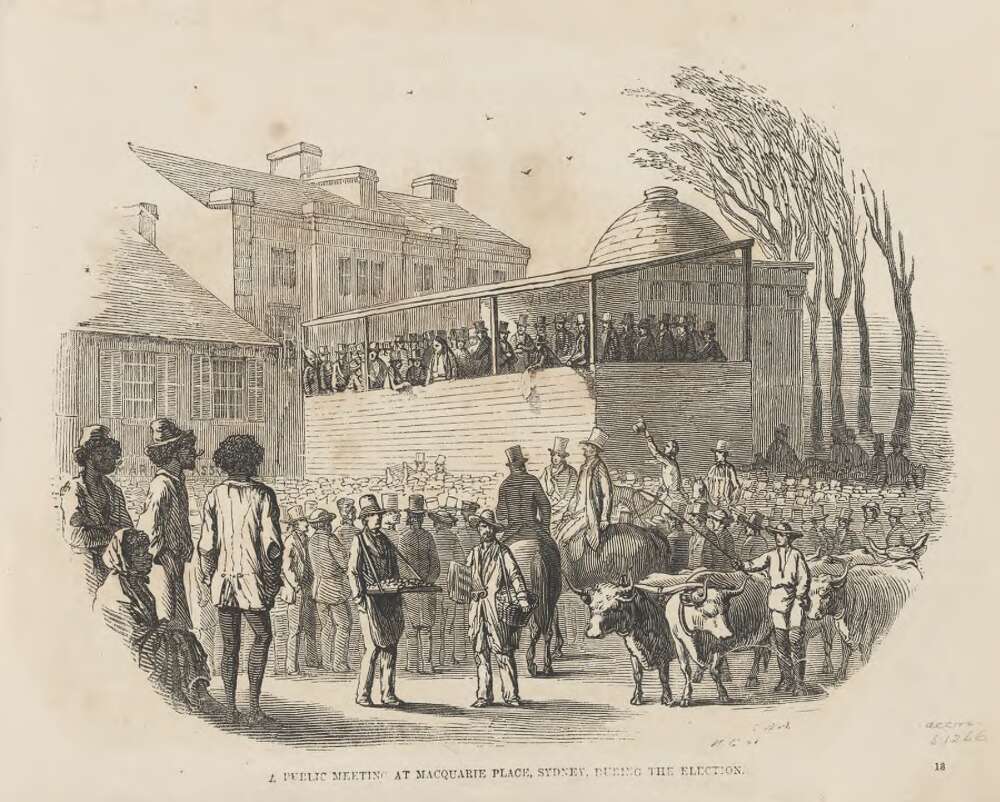

Public meeting at Macquarie Place during the election 1857, National Library of Australia (nla.pic-an8021127)

Public meeting at Macquarie Place during the election 1857, National Library of Australia (nla.pic-an8021127)

Temperance and the ‘evils of tight lacing’: Susan Beckett

Diagram of Susan Beckett's Bust and Shoulder Supporter in her application to the United States Patent Office, April 1896 (Patent No: US557945)

Diagram of Susan Beckett's Bust and Shoulder Supporter in her application to the United States Patent Office, April 1896 (Patent No: US557945)

Mrs Beckett's Lectures, Daily Telegraph ,18 October 1895, p7 via Trove

Mrs Beckett's Lectures, Daily Telegraph ,18 October 1895, p7 via Trove

Vanessa Finney, Capturing Nature: Early Scientific Photography at the Australian Museum 1857-1893

Vanessa Finney, Capturing Nature: Early Scientific Photography at the Australian Museum 1857-1893

Vanessa Finney, Capturing Nature: Early Scientific Photography at the Australian Museum 1857-1893

NewSouth Books, 2019, 654 pp., ISBN: 9781742234984, p/bk, AUS$49.99

Let me declare a point of self-interest before I say too much about this insightful and intriguing book. I confess to having a long history with both photographic practice in cultural institutions and (albeit, a fair while ago), a mediocre stab at a PhD in zoology, taxonomy and identification and management of fishery species. And for my Honours thesis, I was the grateful recipient of some fine x-ray photography taken by staff at the Museum, the very same inheritors of the skills and traditions which Finney’s book chronicles in considerable detail. So I write this, somewhat as an insider, a practitioner, a user and an appreciator of scientific and technical photography. Finney’s book delivers both a record of the evolution of scientific photography in Australia alongside an engaging narrative of some of the key people who shaped the Australian Museum’s place in colonial Sydney. Gerald Krefft and Henry Barnes loom large in this book and in some respects, were in the right place at the right time. For the Museum, as Finney says, the 1860s marked a lucky confluence of skills need, experience and technology. Krefft had established his natural history credentials as a member of the Blandowski collecting expeditions through Victoria in 1856-57 and after a few years as assistant curator he was appointed officially as Curator in 1864, a position he held for 10 years. Barnes’ role evolved from simple specimen preparation to staging, articulation and photography. In an almost feudal manner, Barnes passed both the skills and the position down to his son – in fact, including his brother and his son, the Barnes family contributed over 120 years service to the Museum. It must have been a crowded and often chaotic location, with most of the staff, their families and pets living at the museum. Krefft was followed by Edward Ramsay who also recognised the role of photography in recording, arranging and managing the Museum’s growing collections. The late 1800s were a revolutionary time for natural history, seeing the transition from hobby to discipline, from Victorian gentleman collector to professional scientist. Krefft was an early supporter of Charles Darwin’s theories and corresponded with him, discussing topics such as photographic images of specimens found in the Wellington caves as well as problems with layout of the Long Gallery (in which he included a hand drawn, brown ink diagram of “women young and old contemplating a human foetus”). Concurrent to the evolution of scientific thought and practice was the invention and rapid development of photography, the skills and techniques of which were quickly put into service of science. Though aware of the benefits of photography, the museum Trustees were reluctant to fund it adequately and both Krefft and Ramsay used their own personal cameras and equipment at work for many years. The museum’s first purpose built photographic studio and darkroom was not completed until 1897. The Krefft and Barnes partnership fully introduced photography to the Australian Museum and allowed the institution to record and share its collection with the world. Trading and networking were key ways for museums and ambitious curators to build both collections and reputations. In 1874, Edward Ramsay was appointed as Curator, replacing Krefft, who had lost support of the Trustees after a number of unfortunate and colourful incidents that included the theft of some gold specimens, and seizure of a parcel of “obscene” photographs that Henry Barnes had hidden under his work bench. Ramsay introduced a more measured approach to museum management and transformed the Museum by hiring specialist assistants, experts in each animal group. He initiated indexing and consolidation of the growing photographic collection into albums. Somewhere along the way, the negatives and prints rose from simply being a useful record of the physical collections to be a valuable collection in its own right. It is fortunate that, more than 150 years after the images were made, over 90% of the glass plates in the collection have survived. Capturing Nature tells through its main narrative and interesting asides (“Snakes Alive!, “Henry Barnes Day Off” and “Fighting over teeth”), the genesis, growth and consolidation of the photographic collections of the Australian Museum. Finney, the Museum’s chief archivist and librarian, writes with unquestioned authority and deep knowledge of the museum’s photographic collections. Gerard Krefft with the newly discovered Manta Ray, Manta alfredi, 1869. Courtesy Australian Museum

Gerard Krefft with the newly discovered Manta Ray, Manta alfredi, 1869. Courtesy Australian Museum