The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Sydney

[media]Sydney today can be defined as many things – a bit player in a global economy, a society within a larger nation, a particular culture. Its story has been shaped by the things that shape all cities, and also by things that are particular to it alone.

Initial plans to establish Sydney as a dumping ground for criminals went hand-in-hand with other geo-political and economic interests of the British government. Securing trade routes, providing a victualling and ship refitting outpost, and exploiting the fisheries of the southern seas all combined to make the establishment of Sydney a reality. [1]

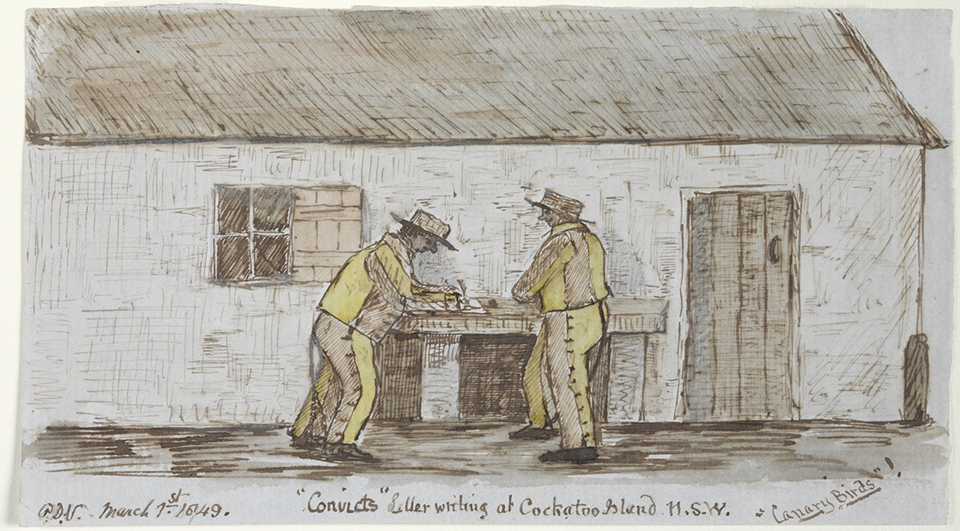

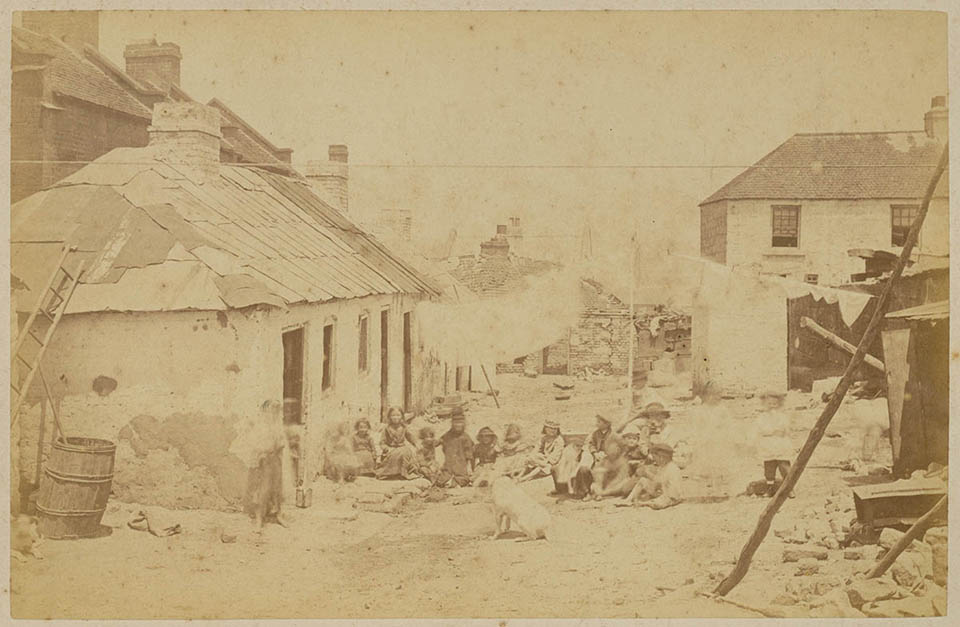

[media]The foundations of Sydney society were laid through a vast social experiment – an attempt to create a whole society using forced labour. Convicts had long been transported to places distant from home, but Sydney was not yet a settlement. There were Aborigines who fished the waters of its harbour and hunted in the surrounding groves and hills, but few Europeans were capable of imagining these people as constituting society.

Culture clash

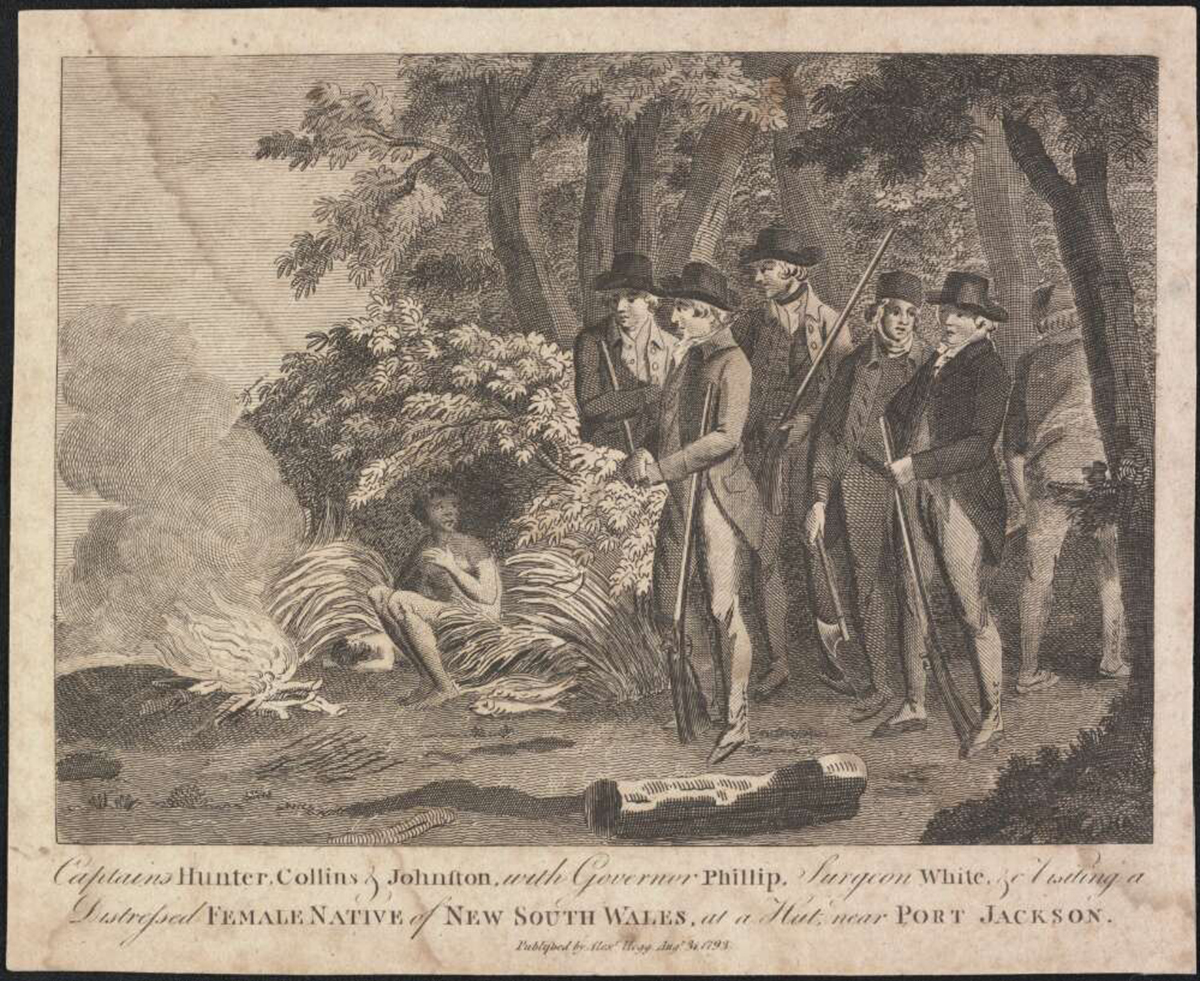

The [media]violent clash of cultures and of economies that inevitably occurred resulted in deep and widespread suffering for these people, unprotected from the Europeans' diseases, and unable to comprehend their acquisitive land practices. Inevitably, however, some cultural accommodations were made. While local Aboriginal people died from smallpox and other miseries in the initial contact period, other Aboriginal people have always been present in Sydney, as they constantly moved into the area from the surrounding hinterland. The history of the place is a shared history, with a continuous Aboriginal presence. [2]

By the [media]time the children of the first Europeans – known locally as the 'currency' generation – were reaching adulthood, free settlers were tentatively starting to arrive, and by the 1830s they were arriving in numbers sufficient to swamp the convict population. Between 1788 and the ending of transportation in 1840, about 80,000 convicts had been sent to Sydney. But according to the 1851 Census, convicts were just 1.5 per cent and ex-convicts 14 per cent of the population. As the prison settlement evolved into a township and eventually into a city, its people were accordingly ever more complex in their origins, occupations and expectations.

Who were [media]they, these men and women who founded the city, built its first buildings, hewed its first roads and gave birth to its children? While the Aboriginal people provided a constant undercurrent of local intelligence and information that assisted survival, it was the European settlers who were intent on manipulating the landscape to conform to their outsider ways. Most of the convicts arrived as young adults. A few had committed political crimes, especially if they happened to be Irish. Some were murderers. But many were convicted of crimes born of desperation in people who were hungry and unemployed, the victims of a cruel social upheaval associated with the emergence of a capitalist industrial economy in Britain and its associated mass disruption of a former village-based way of life.

For worse – or for better?

The [media]brutality of life in the late eighteenth century has generated much debate about the nature of early Sydney society. [3] The story includes acts of great barbarity and petty nastiness as well as of generosity and plain common decency. As a social experiment, Sydneysiders like to think it has been a success.

The [media]popular image of the early decades, when convicts dominated, is of men in chains, of women who were whores, of grisly floggings and soulless barrack accommodation. All these things happened, but this is only part of the story. Punishment was transportation, not imprisonment. How a convict fared in Sydney depended partly on that individual's ability to work the system: a 'keep your head down and your slate clean' approach could result in a good enough life. Possession of professional knowledge or trade skills often led to work and recognition that would never have been possible back 'home'. For someone like Francis Greenway, convicted for forgery, but chosen by Governor Macquarie to design public buildings which are today the jewels in Sydney's early architectural inventory, the contrast was enormous. For many convicts, emancipation resulted in being granted an acreage of land, and even convict labour to help farm it. No wonder so many decided to stay.

The early core of the city

Many [media]chose to settle in areas that today constitutes the City of Sydney local government area. Some of the first humble, privately built cottages were located immediately to the west of the official encampment, in the area that became known as The Rocks (Talla-wo-la-dah). The earliest buildings behind Sydney Cove (War-ran), recreated as Circular Quay by the 1840s, were augmented with development west towards Darling Harbour (Go-mo-ra). Here boatbuilding and wharfage attracted small-scale industry and workshops, and jumbled among all this were houses where an emerging working class lived and laboured.

The [media]upper echelons of Sydney society were located predominantly east of the centre of town, where industry was scarce, until the creation of Cowper Wharf in the 1860s generated a second waterfront facing onto Woolloomooloo Bay. By the mid-nineteenth century, the best addresses were villas in the east, on the Darlinghurst Hill, and out along the road to the South Head, situated with water views, although town houses on Macquarie Street or facing Hyde Park were also acceptable choices for the town's wealthy citizens.

A civic place

They had become [media]citizens with the creation of the City of Sydney in 1842. It would be a fine thing to record that the establishment of municipal government was motivated by an upsurge of civic pride, but it would be closer to reality to argue that it was generated through a concern on the part of the colonial government that Sydney was growing large beyond all expectations, and that there was a need to tax its residents to fund the infrastructure required to keep it functioning and in good health.

The City of Sydney was [media]bounded by the harbour to the north, West's Creek which discharged into Rushcutters Bay to the east, Cleveland Street to the south, and the line of Cooks River Road (now City Road) continuing onto Blackwattle Bay, in the west. While the central area between Darling Harbour and Hyde Park has always been known simply as Sydney, the City of Sydney also took in areas with the local names of The Rocks, Millers Point, Pyrmont, Ultimo, Chippendale, Surry Hills, and Woolloomooloo. Later Darlinghurst, East Sydney, Potts Point, Elizabeth Bay and Haymarket became recognised places as well, and over time other place names have been appended to smaller sections of the city.

These boundaries for the City of Sydney remained constant until the twentieth century, when they shrank and expanded a number of times at the behest of the state government, which has always used local government as a plaything in its attempts to maximise its own urban power. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, in addition to the traditional nineteenth-century areas, the City of Sydney includes Glebe, Paddington, Waterloo, Alexandria, Erskineville, Camperdown, Darlington and parts of Newtown. All of these have at times been municipalities in their own right. [4]

From early vision to complex metropolis

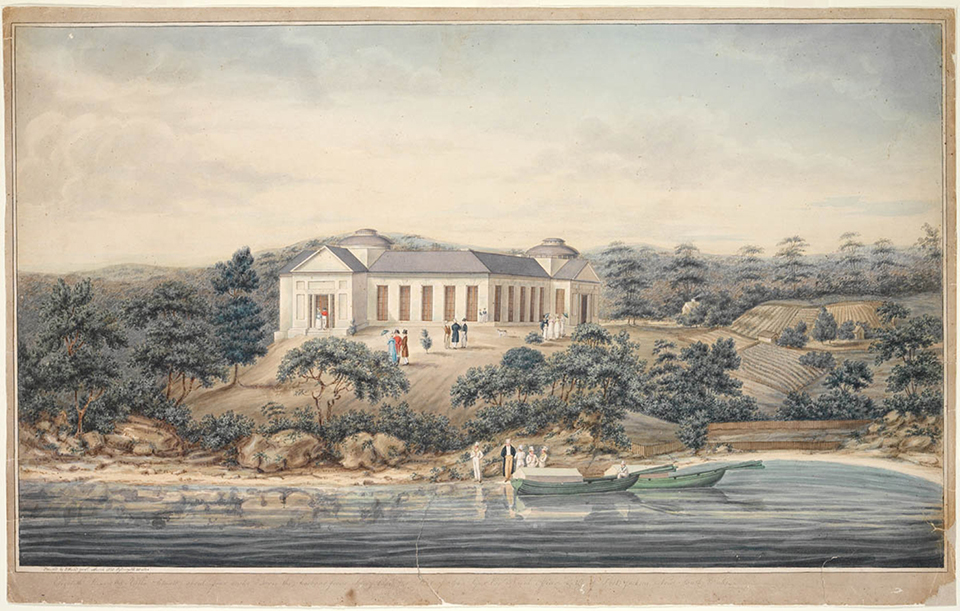

The [media]early decades of settlement have bequeathed to Sydney a haphazard street layout and a number of fine buildings in the City of Sydney, and at other places where early administrative processes were concentrated, particularly in Parramatta but also at Liverpool. Many of them are associated with the period of the governorship of Macquarie, who, with his wife Elizabeth, stands out among Sydney's early rulers for having some vision of the possibilities of a future city. If awards were to be given for the most outstanding piece of urban design from these early decades, it would surely go to the Macquaries for their visionary creation of the Botanic Gardens on land reserved by Phillip as the governor's domain. Located on ground that spills down to the harbour at Farm Cove (Wuganmagali), it is not only a precious place in the heart of central Sydney, but symbolises the inescapable truth that what makes Sydney beautiful is not the handiwork of human intervention so much as the ongoing interplay between its natural and built forms.

Beyond the City of Sydney, suburbs developed, and beyond these, hamlets and villages that over time have been subsumed into the greater metropolitan area that is now known as Sydney. Suburbs constituted themselves as municipalities after the Municipalities Act of 1867, and as with the City of Sydney, growth and diminution of boundaries occurred at the behest of the state government. Attempts at creating a Greater Sydney urban government have never succeeded, for similar reasons of state control. With Sydney forming such a large part of the state economy, the state government has always understood that if it did not control Sydney it would not control much at all, and accordingly both local and urban-wide powers have always been kept in check.

For the same reason, many of the functions traditionally exercised by the City of Sydney and other local governments in metropolitan Sydney have gradually been taken over by state authorities. One obvious consequence of this is that Sydney residents often find it difficult to understand which parts of a complex government organisation have oversight of specific urban functions.

A second consequence is that people do not always know which municipality they live in, preferring to identify more strongly with their suburb. Suburbs often do not have any formal boundaries, and their size varies over time, especially when denser settlement patterns encourage the carving out of new suburbs within the boundaries of areas bearing older place names; but local understanding of place and suburb is usually strong, and there is a logic to these namings which does not apply to local government areas.

A fine provincial city

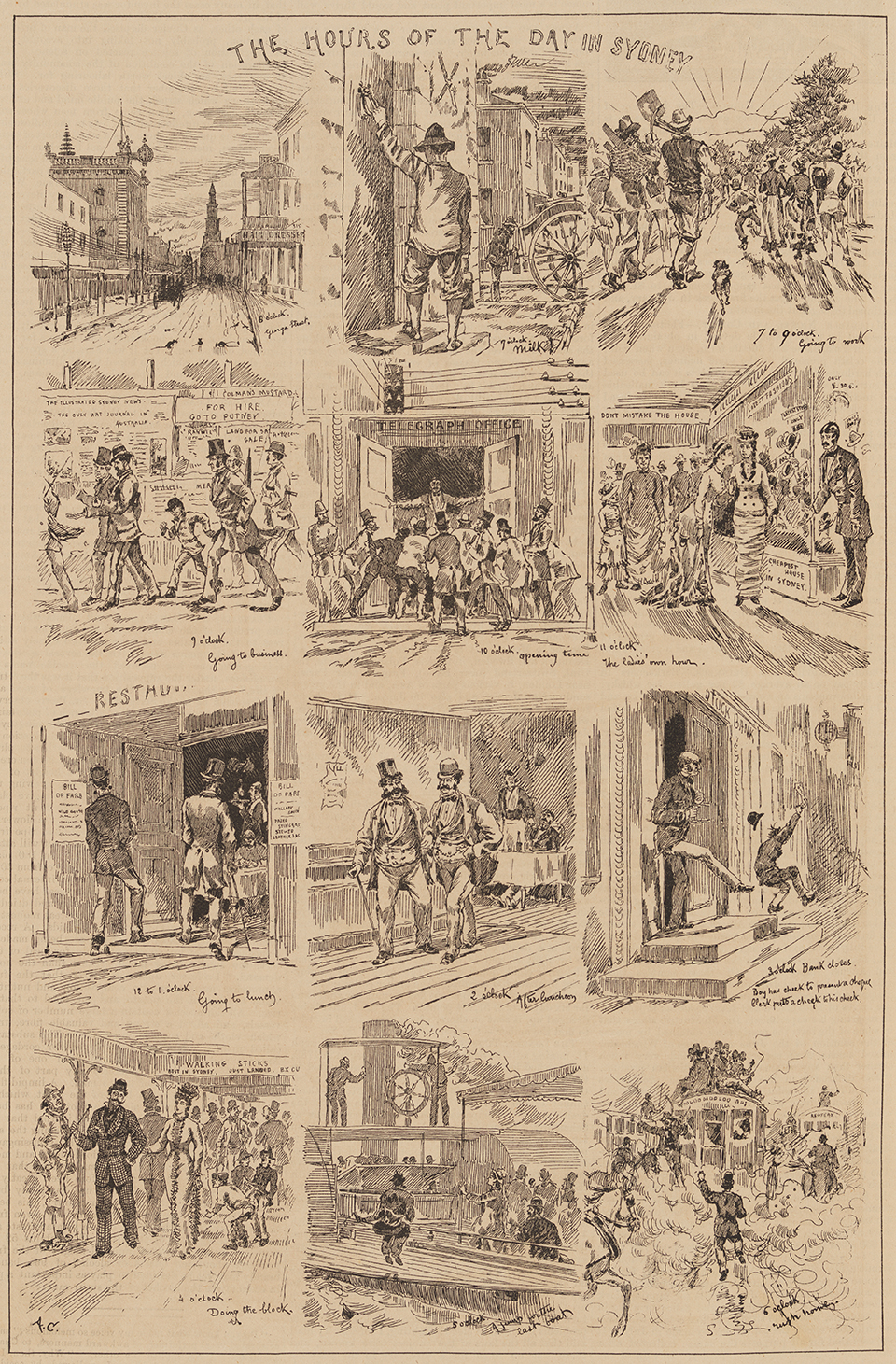

In the [media]second half of the nineteenth century, Australia's urbanisation was rapid by world standards, and much of the gold discovered in rural areas and assayed at the mint in Macquarie Street was used to fuel an urban property boom. Sydney's population mushroomed, and in the centre of the city older convict buildings and Georgian townhouses were demolished with alacrity to create a larger and more ornate Victorian place, characterised by substantial public buildings such as the General Post Office, the Town Hall, and buildings to house the headquarters of various rapidly expanding government departments. Typically no more than three stories of generous height, and often squatting over whole city blocks, these fine sandstone buildings remain today as the dominant reminders of Sydney's period as a large and prosperous late-nineteenth-century provincial city.

With this [media]growth also came the rise of suburban Sydney. Cartoonists of the day portrayed a remorseless march of bricks and mortar across the bush, as the physical dimensions of the city grew ever more bloated. But compared with Melbourne or Adelaide, the march was slower in Sydney, due to complex topography and a failure of political will to fund a comprehensive rail network. The deposit of housing was denser, with suburb upon suburb of tightly packed terraced houses built to face each other across narrow streets. Compared with the southern cities, Sydney was characterised as 'English' in appearance, staid and most definitely playing second fiddle to a brash, go-ahead, 'American' Melbourne.

Rivalry [media]between these two cities was a favourite topic of journalists and social observers from this time, and echoes of this remain today. The nation's first international exhibition, held in 1879, was intended to put Sydney on the map as the nation's first city, and there was much local pride in the huge, domed Garden Palace that reared up in the Botanic Gardens to house the event. But along with the pride there was considerable doubt about Sydney's capacity to stage such an event, and when the Palace burnt down only a few years after it had been built, the symbolism was seemed clear to many observers. Melbourne took the exhibition after it had done its time in Sydney, housing it in a fine exhibition hall which remains today.

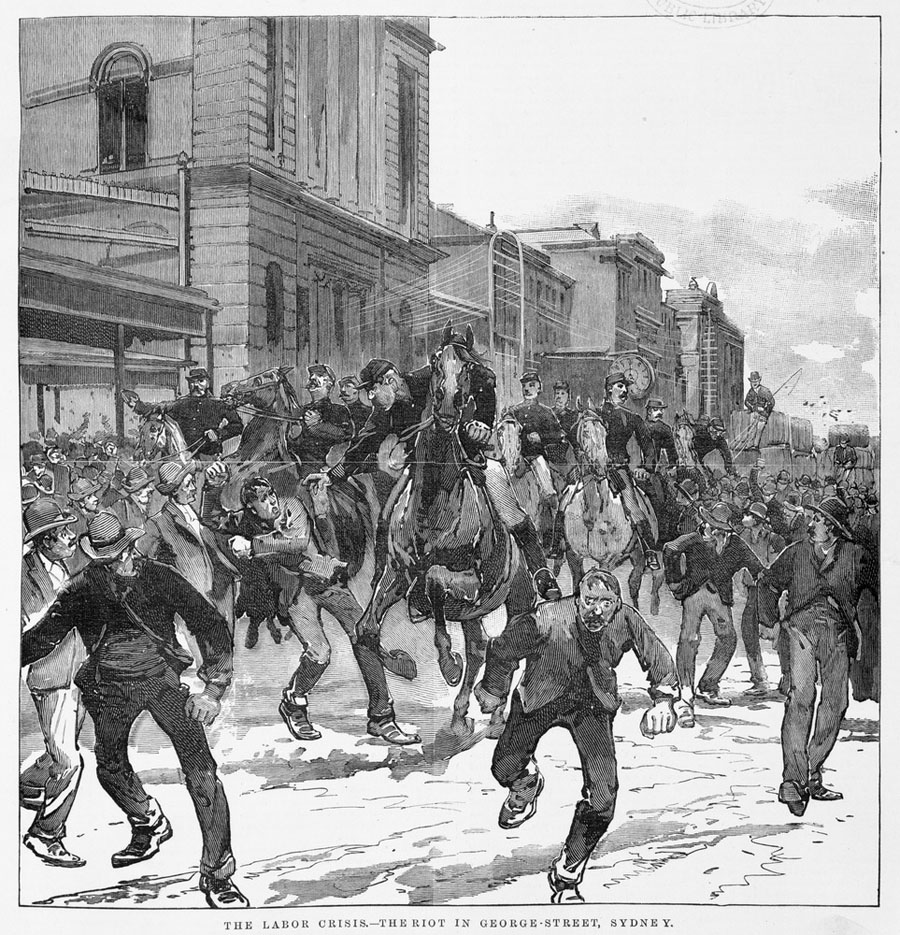

Suppression of [media]memories of convict origins was integral to the hope of creating a society better than any produced elsewhere. For many, this was measured in houses, grand public buildings and wealth in the bank. For others it was a vision of creating a new society, underpinned by a new unionism that would deliver fair working conditions for all, a growing nationalism, and even republicanism. But revelations about increasingly uneven wealth distribution, high infant mortality rates as bad or worse than those in many provincial English towns, paltry sewerage provisions, and a failing water supply resulted in growing doubts as the long economic boom turned into a major depression by the final years of the 1880s. [5]

Depression strikes

The [media]closing decade of the nineteenth century was one of social and economic turmoil. Widespread industrial strikes and lockouts disrupted the waterfront and closed down factories. Banks failed. Larrikin 'pushes' terrorised the residents of poorer localities. Urban building faltered, and mortgagors could not keep up their payments.

This [media]decade was one of creative turmoil as well, as local poets and writers, stimulated by the collapse of the self-satisfied certainties of the boom years, began to explore the themes of poverty and wealth in a Sydney-specific setting. Henry Lawson, who is arguably the country's most famous poet, penned perhaps the greatest love poem to Sydney in his 'Sydney-side', which extols the wonders of the city through the voice of a homesick expatriate who knew that 'the harbour-lights of Sydney are the grandest of them all'. But he also wrote bitter words grounded in Sydney's industrial heartland, such as his poem 'Faces in the Street', which begins with the angry lines:

They lie, the men who tell us, in a loud decisive tone,

That want is here a stranger, and that misery's unknown

and [media]ends with a call to revolution to confront the 'terrors of the street'. Though the journalist and socialist trade union organiser William Lane lived and worked in Brisbane, he chose Sydney as the setting for his didactic novel The Workingman's Paradise, using government enquiries into Sydney's factories and workshops as fodder for his story, describing the sweatshops in the back streets of Surry Hills and the unemployed homeless sleeping out in the Domain. [6] And it was from Sydney in 1893 that he sailed with 200 supporters to establish a 'New Australia' in Paraguay, disillusioned with the failure of the old one to deliver up a better world.

Improvers get to work on Sydney

But for others, the downturn of the 1890s increased introspection concerning the physical state of the city and the narrow base of the urban economy, with the resulting emphasis in the following decades on support for a wider range of urban industries and for the provision of urban amenities.

The city's [media]water supply, intermittent by the late 1880s, became more secure when the Nepean Dam came into use. Ocean sewer outfalls at Bondi and Malabar took disease-creating waste away from built-up areas, and infant mortality rates fell. So, too, did birth rates, as the 'new woman' regulated her own fertility and focused on getting a better education. A system of tramways gradually extended its tentacles into outlying suburbs, providing more mobility, while the shock of an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1900 gave the government the excuse it was looking for to intervene to clean up and modernise the city's wharves at Millers Point. Under the banner of the greater public good, large tracts of privately owned waterfront, adjacent housing, stores, churches and pubs were resumed by the government and knocked down. Model housing, including Sydney's first 'flats', was erected, new roads were carved out of the rocky shoreline and state-of-the-art wharves and shipping facilities were constructed. [7]

This was the [media]beginning of several decades of resumptions and demolitions in the centre of the city and in the oldest inner-city residential areas, done in the name of slum clearance, for the provision of wider roads and a new Central Railway Station and to make land available to industry and manufacturing. A Royal Commission on 'the Improvement of Sydney and its Suburbs' reported in 1909 on a number of transport and planning schemes that addressed the twin desiderata of a modern city – efficiency and beauty. Though this had limited practical impact at the time, over the next half-century many of the recommendations of this commission were slowly implemented.

Where have all the young men gone?

The [media]early years of the twentieth century witnessed a slow return to growth, but it was partial, and for many unemployed youth, the advent of World War I offered their first job. And their last. High casualty rates left a skewed population with an excess of young women who would never marry, and this female surplus spearheaded the building of Sydney's first flats – particularly in Potts Point and Kings Cross – places for the 'new working girl', who would continue to be referred to as a working girl long after she became old.

A [media]further devastation of this war was the visitation of Spanish flu in early 1919. While this world pandemic affected many Australian settlements, Sydney was particularly hard-hit. It was estimated that as many as a third of the population contracted the disease, and of the thousands who died, many were young adults. The flu did not have the impact of the bubonic plague in altering Sydney's built form, probably because it was so severe that the authorities were fully stretched just dealing with the immediate day-to-day issues. Houses that held infected people were required to fly the yellow flag, schools and the university were closed, and temporary hospitals were set up at the Showground and in public halls across Sydney.

On a more [media]cheerful note, a flag of a different type flew from the General Post Office in February 1920, announcing the arrival of Ross and Keith Smith, who had flown from London to Darwin for the first time in under 30 days at the end of 1919. Thereafter they encountered mechanical problems and did not make it to Sydney for several more months, but the achievement and its implications for modern communications were celebrated anyway. A huge crowd headed for the Mascot Airfield to welcome this more acceptable symbol of closer ties with the rest of the world.

Down with the slums

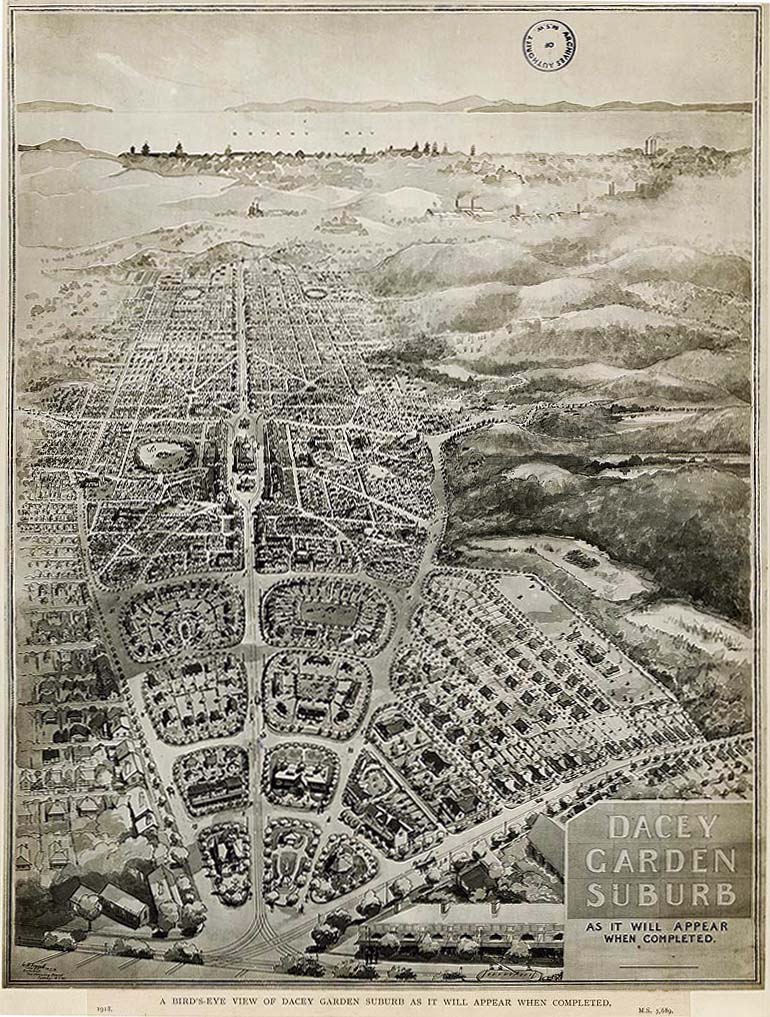

By [media]now it was conventional wisdom that Sydney's inner areas were not good places to live, and that anyone who remained did so only through lack of choice. The suburbs, preferably close to a railway line, were much to be preferred. The early twentieth century supported several kinds of planned suburbs. 'Garden suburbs', such as Burwood and Haberfield, were inspired by British models in direct response to the bleakness of older inner suburbs. Post-World War I soldier settlement suburbs such as Daceyville and Matraville, built on scrubby sandhills to the south-east of the city, integrated housing and community facilities in places fit for heroes. Deliberately mixed industrial-residential southern suburbs such as Rosebery and Beaconsfield heralded a new kind of working-class suburb, where workplaces and residences were to co-exist but not in the older cheek-by-jowl manner now despised by a new breed of town planners.

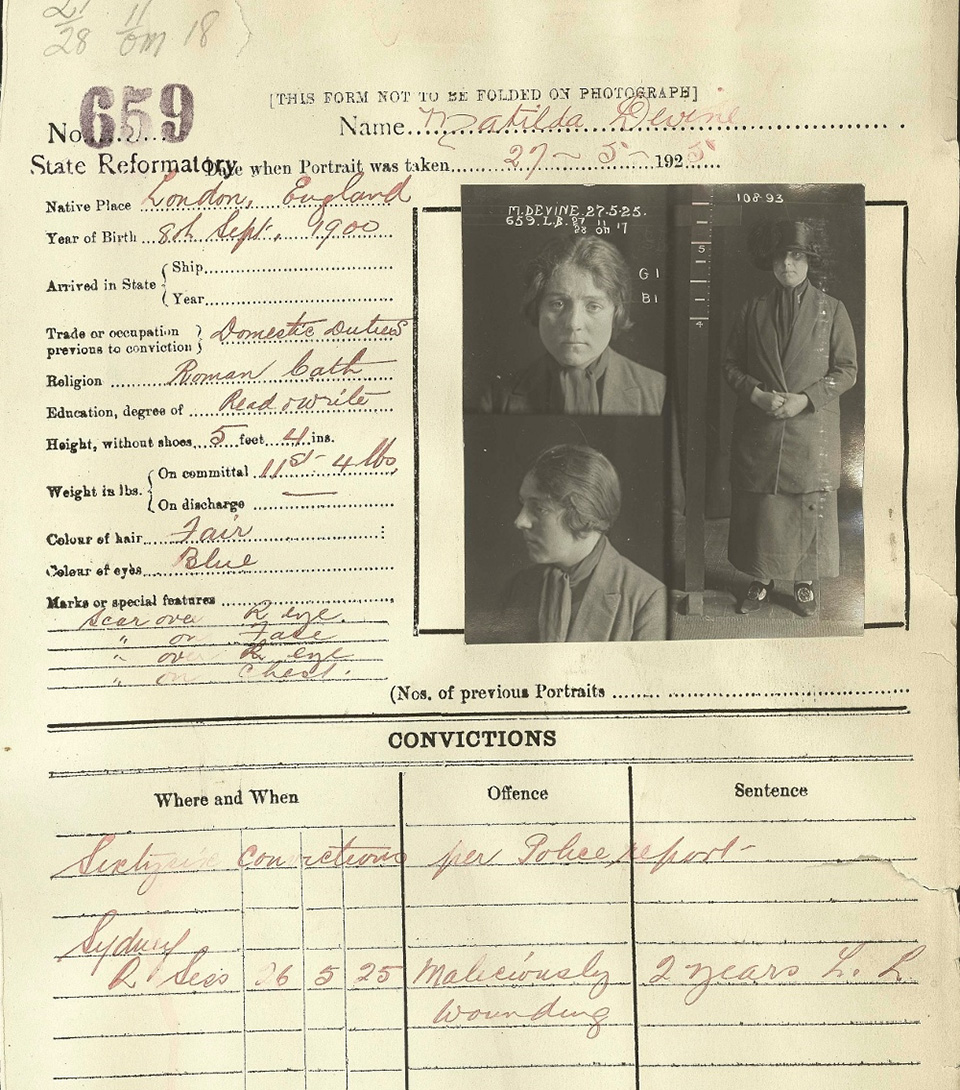

The [media]older inner-city areas became increasingly associated with crime and the emergence of an underworld black economy in the depressed interwar years. While spruikers and real estate agents encouraged a focus on the beauty and wholesomeness to be found in trips to the Blue Mountains and seaside resorts, or the well-being that would be engendered through the purchase of a fine quarter-acre block in the railway suburbs in the 1920s and 1930s, the fictional writings of a new breed of social realist novelists, such as Kylie Tennant and Ruth Park, recorded the raw edge of life for the déclassé as well as for the respectable poor of the inner city. Here the old dream of a workers' paradise was well and truly jettisoned in favour of tales of poverty, overcrowding, street gangs and a street life where the would-be respectable were forever rubbing shoulders with gangsters, sly grog traders, madams, pimps and drug racketeers. These tales are often cited as some of the best historical records of the time. [8]

Depression again and a change in economic direction

Genuine inner-city [media]poverty was exacerbated by the fact that many of the older factories and industries that were located in these areas suffered the greatest contraction during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Forced evictions and confrontations with rent collectors became the visible measure of economic suffering in places such as Darlinghurst and Newtown, while the emergence of tent and shanty towns on the southern reaches beyond Randwick and as far away as the Royal National Park told the same story. At least one suburb, Hammondville, emerged from an organised self-help movement to construct houses cooperatively. [9]

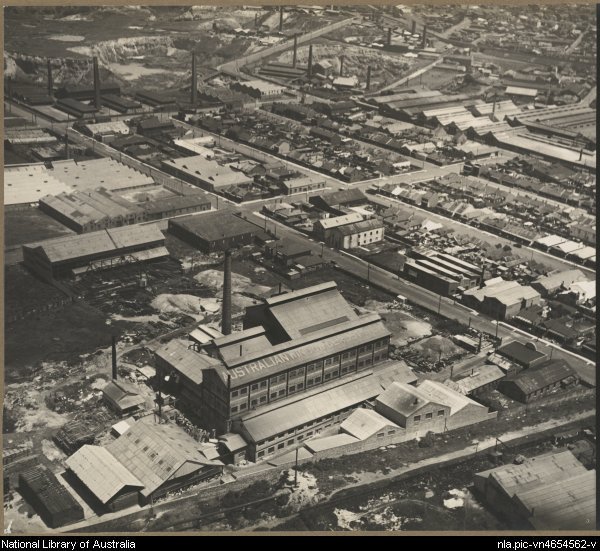

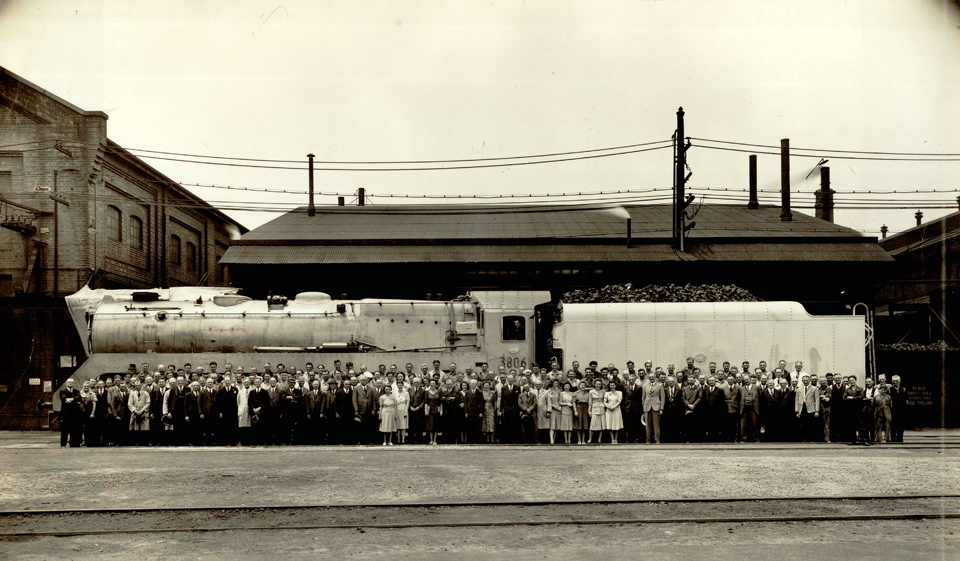

Particularly in the [media]southern suburbs, the new manufacturing urban economy was expanding, to supplement traditional industries tied to rural products and the building industry. Steam technology was supplanted by electrification, and by the 1920s borrowings from Britain were being strongly directed into these new industries. Large power stations generated electricity to move the city's trains and trams and power an increasing manufacture of goods.

The 'world's greatest Bridge'

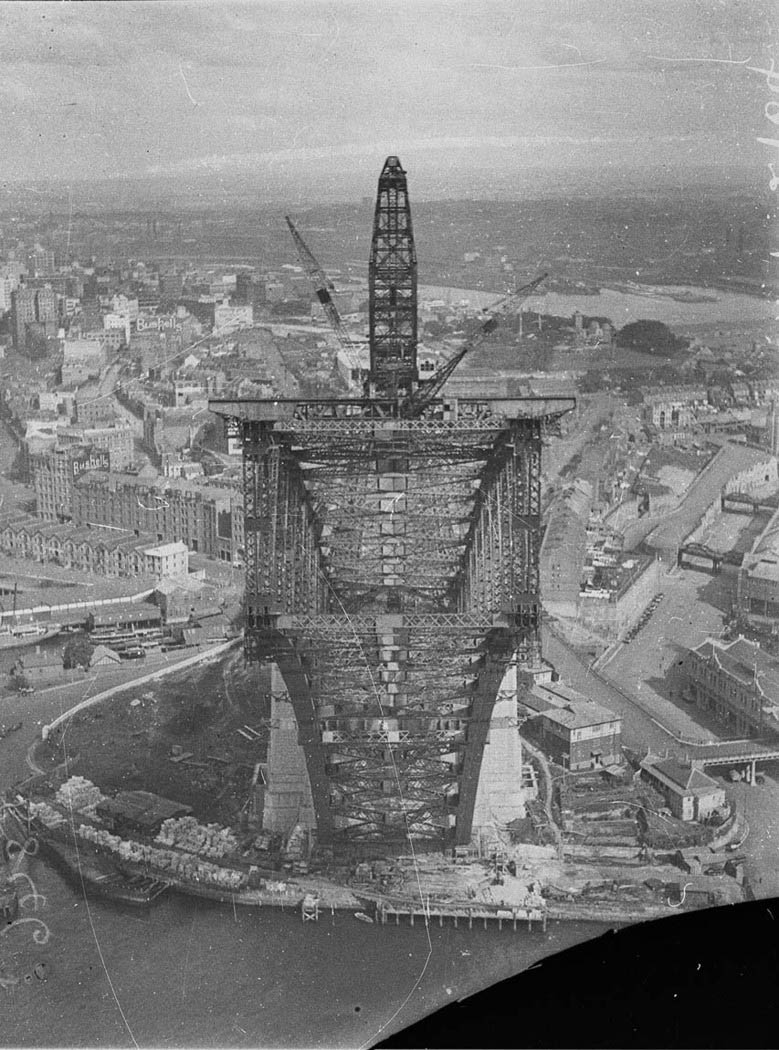

The [media]construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge provided work for some in these dark years, and perhaps more importantly it played a useful role in creating community cohesion. [10] In the collective memory of Sydneysiders, everyone was there at the opening of the Bridge. Initially derided by many as the North Shore Bridge, it quickly became 'Our Bridge', subject of adulatory songs, poetry, photographic essays and endless self-congratulation. Its great arch dominated the city skyline, and immediately became the symbol of the city to the world.

Yet as has so often been the case with [media]celebrations in Sydney, its opening also generated farce in the form of a man on horseback, brandishing a sword, who appeared out of nowhere to slash the ribbon meant to be cut by the Premier to formally open the Bridge. Captain de Groot was carted away by the police. He was a member of a shadowy ultra-right paramilitary organisation called the New Guard, dedicated to the overthrow of the state's Labor government. It was alleged to have around 50,000 members at its peak, and claimed to be in a position to bring the city to a standstill through disruption of essential services.

The war comes home

But [media]these dark stirrings could not compete with the rumours of war and the rise of fascism in Europe in the 1930s. A steady flow of Middle European immigrants fleeing these developments turned up in Sydney, and though their numbers were not large, many of them subsequently became leaders in industry and commerce. Dating from this decade were the introduction of goulash and schnitzel and the arrival of the 'delicatessen', offering exotic wursts and pickles. Bohemian Kings Cross and a few enclaves in the city were viewed by many as oases of European sophistication in an otherwise Anglo city.

World War II was [media]positive for manufacturing, and many women found work in munitions factories as well as in the more traditional areas of the rag trade and food manufacturing. Once the arena of war moved to the Pacific, Sydney was uniquely placed, close to troops who needed to be fed and clothed.

If World War I was [media]remembered as introducing many Sydneysiders to the world, World War II threatened to bring the world to Sydney. In May 1942, Sydney was invaded, when three Japanese midget submarines got inside Sydney Harbour. One was sunk, one was blown up by its own crew, and one beat a hasty retreat after blowing up the ferry Kuttabul, being used as a naval depot. This close encounter riveted Sydneysiders, who had so far only learned their war lessons from Cinesound newsreels at the picture palaces.

People remember the [media]war as a time when the colour went out of Sydney. Shop windows were not lit up, and eventually houses too were 'browned out'. Red suburban buses were painted grey, ships slipped out of the harbour in silence, and the coloured stripes on their funnels that indicated which shipping line they belonged to were all camouflaged in war-time khaki brown. Beaches were strung with barbed wire and the clock tower of the General Post Office was removed to prevent it becoming a target.

Others [media]recall the glamour of the American GIs on 'R & R' in Kings Cross. Girls took up with them, possibly for the chocolates, stockings and cigarettes which local lads could not supply. Understandably, Australian men recall the visiting Americans with less affection than do the women.

The largest construction project of the war years was the Captain Cook Graving Dock at Garden Island, now joined to the mainland. Although this was not completed by war's end, it contributed significantly to the naval and maritime industry of the city, and visually to the industrial infrastructure of the harbour.

Postwar growth

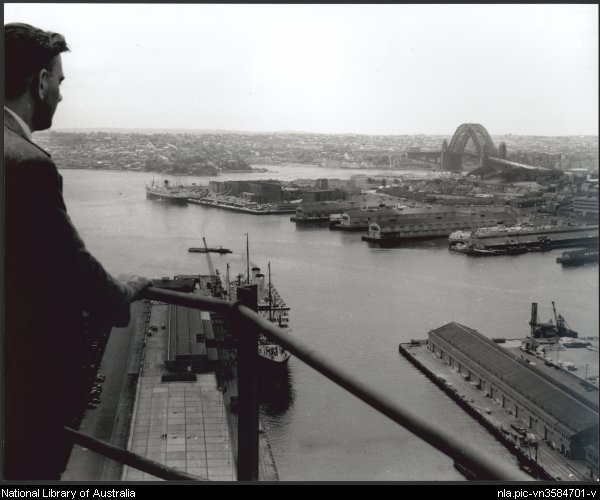

By the [media]late 1950s, the trade of Port Jackson was expanding. The inner reaches of the harbour were covered in busy wharves, with a backdrop of wool stores, grain silos, timber yards, coal loaders, and bond stores. The long room at Customs House at Circular Quay was crowded with brokers and clerks, ticking off ships' manifests, intercepting contraband, impounding and releasing shipments and packages, minding and judging the entry of people and things and ideas into Sydney. Outside, the pubs were all early openers, quenching the thirst of wharf labourers and providing congenial space for doing the deals that always get done around any urban waterfront.

Behind the Quay [media]were the six- and eight-storey offices of the commercial centre of a city of two million people. Many of the city workers who crowded the buses and the remaining trams to make the journey to work and back home still lived in nearby working-class suburbs like Pyrmont, Glebe and Redfern. In all these places there were also many who worked locally, thousands at the railway yards at Eveleigh, at whitegoods and motor industry plants in Waterloo, and thousands more on the wharves that stretched from Woolloomooloo to Rozelle Bay.

Sydney had [media]been a manufacturing city since protective tariffs had been introduced back in the 1920s. But there was an intensification of manufacturing in the 1960s, spurred on by cheap imports of raw materials, booming world markets for minerals and agricultural products, and large-scale immigration. It is often remarked that post-World War II immigration contributed variety and sophistication to our collective palate, and even produced a state premier or two. But for many immigrants their role was as cannon fodder for a growing number of factory jobs. By 1970 over 30 per cent of all Australian manufacturing jobs were in Sydney

The postwar immigration program brought some of Europe's displaced and war-shattered people to the city. Preference was given to young men and to British immigrants in the first instance, but when these could not fill the demand, entry was permitted from other northern European countries, and then from southern Europe. A hitherto fairly Anglo society was not backward in taunting and discriminating against 'reffos', 'Balts', 'wogs' and 'Eye-ties', as factories and construction sites all over Sydney began to resonate to the sound of a multitude of languages. They're a Weird Mob, written by Nino Culotta (John O'Grady) and published in 1957, went through many reprints and was made into a popular film. Set in Sydney, it explored the trials and tribulations of an Italian immigrant expected to 'assimilate' to 'Strine' (Australian) culture.

While [media]immigrants were essential to the city's economic expansion, they were also essential in the preservation of much of the inner-city housing that was by now widely shunned. Unable to afford anything better, and not so critical of dense urban living, Greek, Italian and Lebanese migrants painted and mended whole precincts of old terrace houses, thereby saving them until the next generation of Sydneysiders decided to value them as 'trendy'.

By the 1970s the idea of 'assimilation' had given way to that of 'multiculturalism', and to the postwar European migrants were added growing numbers of people from Asia, as the White Australia policy that had severely restricted Asian, particularly Chinese, migration since 1901 was dismantled. Today it is impossible to imagine Sydney without the cultural richness that its complex population has created.

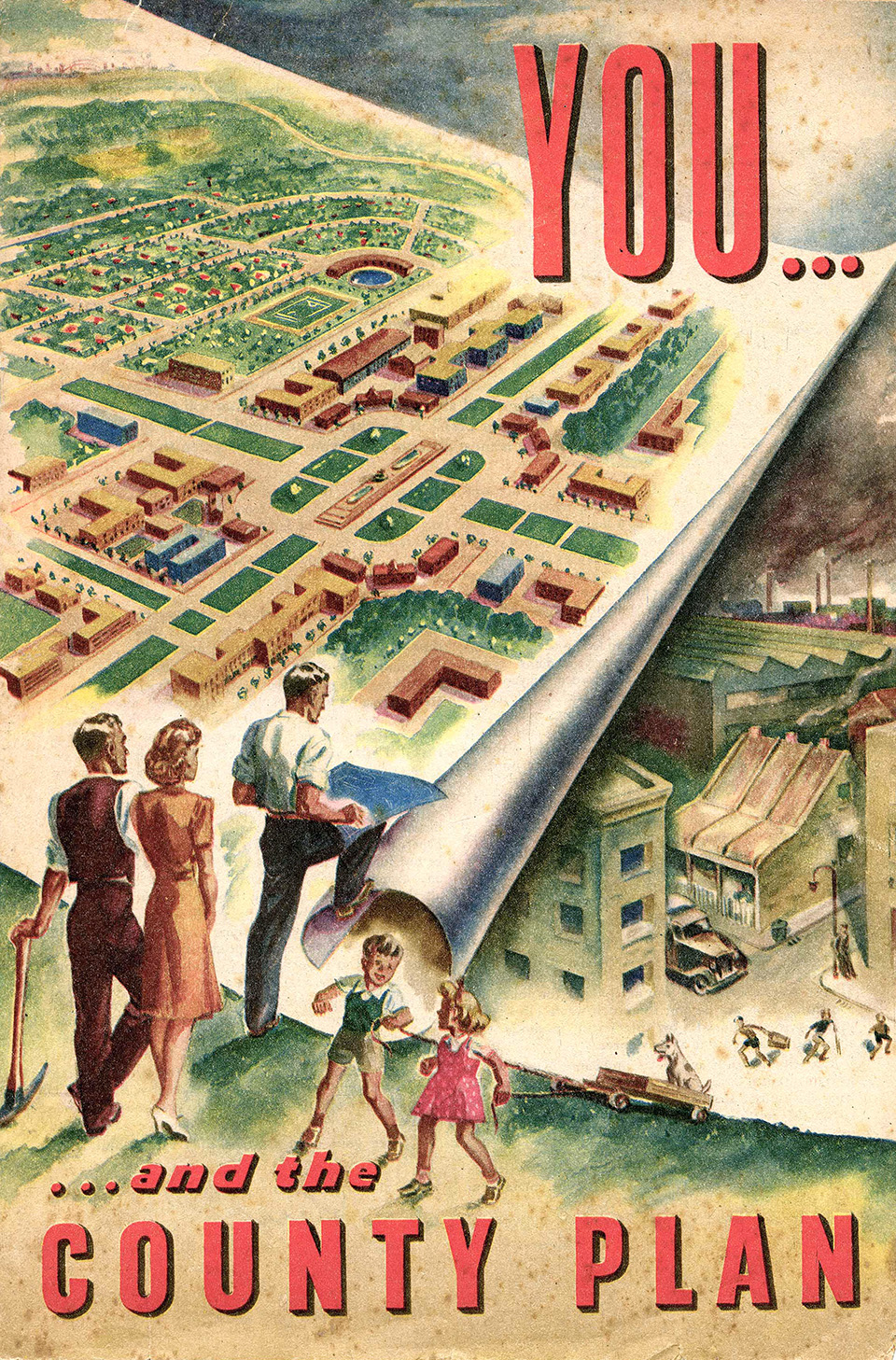

Along [media]with the immigrant, the other ubiquitous arrival in Sydney in the postwar decades was the car, which became an affordable commodity for ordinary citizens by the 1950s. Where the railways had failed to go, the car succeeded. Enthusiasm for this new form of transport turned Sydney into a sprawling metropolis, with development often ignoring planners' visions of an ordered expansion. The ambitious Cumberland County Plan, which envisioned planned dense urban nodes and expansive green belts, was dismantled as project housing companies profited from a pent-up demand that spread out into new suburbs. Public amenities and public transport lagged behind private housing, and as late as the 1970s many of the outer western suburbs were not even sewered. [11] Public housing, which emerged as a serious player in the housing market at this time, was similarly bereft of services. The massive Green Valley project, which between 1960 and 1965 delivered 20,000 houses and a heap of social problems to land that had previously been orchards and vineyards, ultimately became a textbook example of how not to provide public housing.

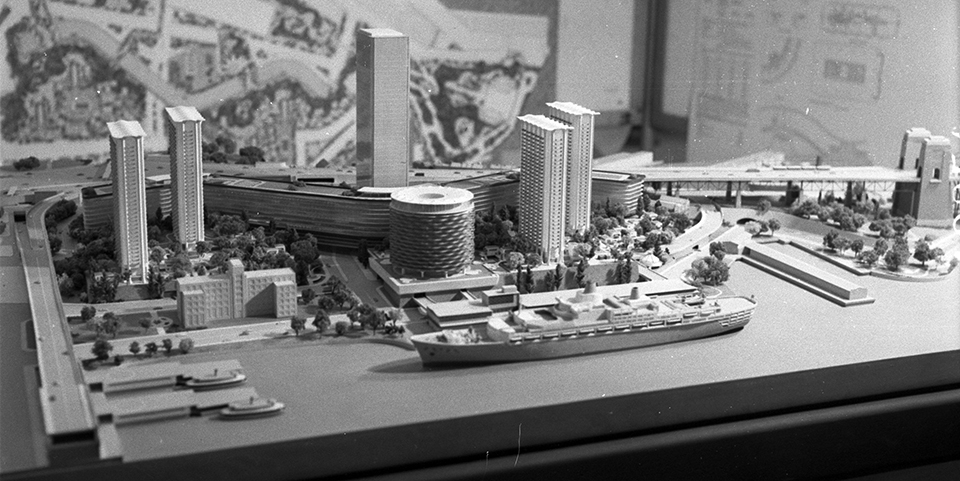

And [media]while the city sprawled, in the old centre it was rushing skywards. In 1957 the legal restriction on building higher than 150 feet (45 metres) was lifted. This had effectively held building at a maximum of 12 storeys for half a century. In 1962 the AMP building at Circular Quay reached 26 storeys, and people paid six shillings to go to the top-floor lookout. The city sky filled with cranes, and anyone who wanted a job could get one in the construction industry.

Changing and staying the same

In the 1960s and 1970s, Sydney was the [media]scene of the kinds of social upheaval that were common across the first world, as people took to the street to protest against the Vietnam War, to agitate for women's and gay rights, and to express concerns about the state of the environment. But it was Sydney's response to its own urban growth that put it on the global map. While many found the new Manhattan-style glass and steel towers exciting, others worried over loss of heritage and the destruction of what was unique to Sydney.

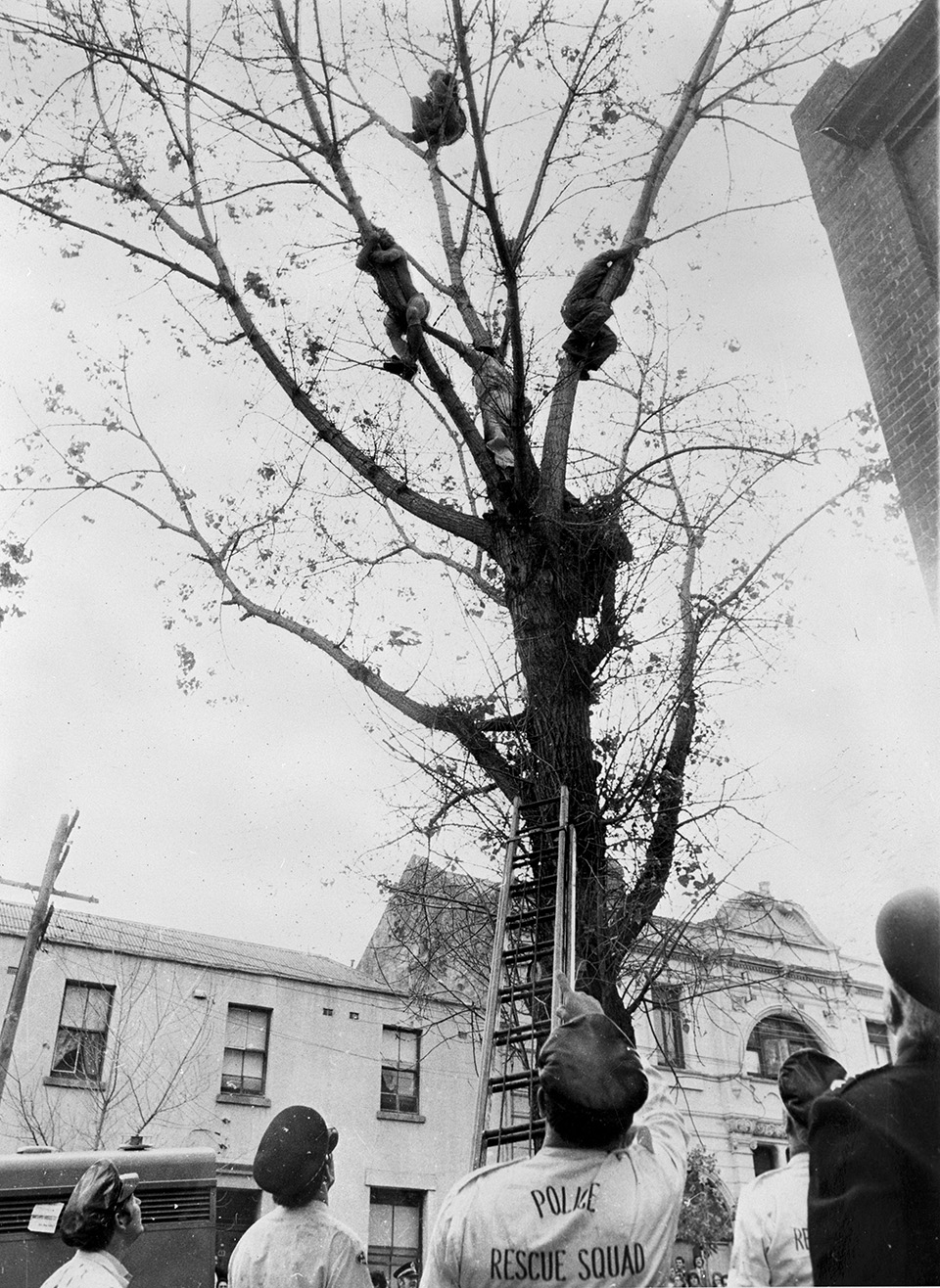

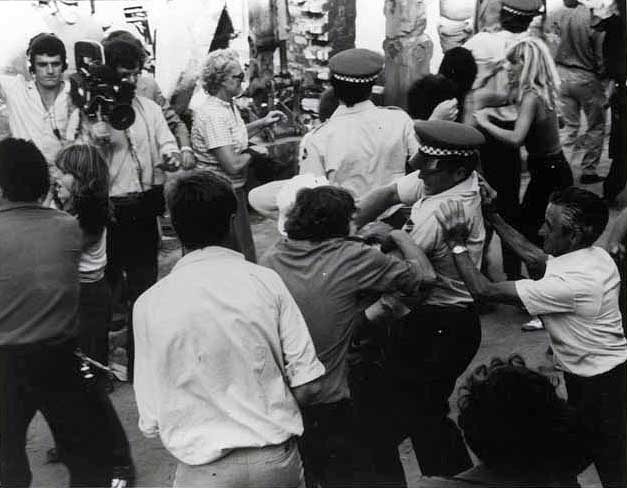

Local [media]residents groups such as the Glebe Society and the Paddington Society emerged to fight against what they considered the unacceptable face of progress. The catalyst for such groups was often resistance to projected freeways that threatened to cut localities to pieces. While there had been voices concerned with heritage issues in earlier decades, these interests were given a huge leg-up by what came to be known as 'green bans'. The Builders Labourers Federation (BLF), hitherto a rough and corrupt trade union, along with some related unions, joined forces with resident action groups, known as RAGs, across Sydney to put a halt to numerous developments and demolitions. Green bans on much of The Rocks, [media]planned for intensive commercial development, captured the imagination, as night after night the nation's televisions screens showed crowds of angry people defending their territory in skirmishes with the police. In 1968 the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority had been established to facilitate rapid change in The Rocks, and it was partly this cavalier move on the part of the state to remove the oldest of Sydney's residential places from the democratic processes of local government planning, that focused community anger.

Green ban-supported [media]battles preserved numerous places, from harbourside Kelly's Bush in Hunters Hill to the old Pitt Street Congregational Church. State freeway plans were shelved and Commonwealth intervention by the Whitlam Federal government resulted in the preservation of inner-city housing, notably most of Woolloomooloo and the run-down properties on the Anglican Church's Glebe Estate. The bans resulted in violence, gaolings and a murder or two, as well as inspiring several good documentaries and fictional films.

The concentrated period of the green bans lasted only a few years in the early 1970s, but the long-term results remain in significant areas of Sydney which retain their historic fabric today, as well as in heritage and environmental legislation introduced in the mid-1970s. [12] It would be unwise to be too sanguine about these things. There is a strong case for arguing that, in this city, developers have always held the upper hand, but in Sydney there is now room for retaining at least some of the old among the glitz of the new. At the same time, anti-pollution laws began to clear the air, as the pall of smog that hung over the city each morning until at least lunchtime was gradually brought under some control.

In a [media]city where 'blokes' were very much at home, there was also a growing acceptance of differences in gender and sexuality. In 1978 Sydney's first Gay Mardi Gras parade along Oxford Street was subjected to police harassment, and ended in mass arrests. But eventually many of the charges were dropped and by the following year the laws restricting public demonstrations had been relaxed. This event went on to become one of the largest celebrations of gay and lesbian men and women in the world, seen by a worldwide audience on TV and the internet.

The 1960s and 1970s also [media]witnessed an increasing number of Indigenous people coming into the city from rural areas, especially to Redfern where Aboriginal housing schemes and support organisations evolved, offering hopes for better things.

New economy, new interests

If the language of the 1970s was comforting to those who wanted a fairer and culturally diverse society, the language of the 1980s was not. The continued rise in importance of Sydney's links to the international economy coincided with global moves to deregulate the market place. By the mid-1980s, foreign capital interests were concentrating on setting up in Sydney. There was also an increased focus of immigration into Sydney, as air travel replaced older patterns of shipping where Melbourne was the first port of call. The 'new' industries were based on finance and high-tech developments, electronics, and increasingly, on entertainment and tourism.

Manufacturing collapsed. The proportion of Sydney's workforce involved in manufacturing was 39 per cent in 1961. This had plummeted to 12.6 per cent by 2001. Between 1970 and 1985 there was an absolute decline, with a loss of around 180,000 manufacturing jobs.

Deindustrialisation happened fastest in the centre where, by the 1980s, factories, powerhouses and woolstores fell silent, or were turned into museums, or clear-felled in preparation for the construction of residential flats, now renamed 'apartments'. Shipping moved progressively away from Port Jackson to Botany Bay and beyond, and the long debate commenced over what to do with our redundant wharves, so long a major visual component of the city.

On a different front, the 1980s was a decade when the spotlight was turned on unacceptable levels of organised crime and police corruption, and the newspapers were full of reportage from several spectacular Royal Commissions concerning drugs, mafia infiltration into licensed club operations, corrupt politicians, and illegal phone tappings, along with a few murders and unexplained disappearances. A shoot-up in inner-city Chippendale, a brutal bashing of a reforming politician, the discovery of a drowned prostitute in an ornamental lake in Centennial Park – it all seemed to point to an underworld of Sydneysiders out of control. It also generated a plethora of publications, often by crime reporters, that covered the crime scene in general, as well as biographies of crime figures such as Lennie McPherson, Abe Saffron, Arthur (Neddy) Smith – these and more became household names for a time. [13]

Meanwhile, after digesting all this through their weekend newspaper reading, new economy workers frequented antique and junk shops on weekends, as they lovingly restored old housing stock. Many traditionally working-class inner-city residents must have felt a tug of emotion as they watched from the urban periphery while the 'basket weavers' removed their handiwork of upgrades of aluminium windows and sticky brick cladding, in favour of restoration of the original timber and plaster, and the prices of their erstwhile slums rose to dizzying heights. The central business district itself was not yet positively engaged in residential growth, but the aspirations were there, to be realised in the 1990s.

Spectacle and celebration

In the 1980s the [media]metropolitan area was redefined as far north as Gosford and west to the Blue Mountains. The population reached 3.5 million by the time the city was ready to party in 1988. Sydney was naturally the focus for celebrations of the bicentenary of European settlement in Australia in January 1988, by this time also described by some as the invasion. Whereas there had been public controversy in 1938 about the version of history portrayed, the 1988 celebrations avoided history, re-enacting instead the arrival of the first fleet in 1770. Historian Beverley Kingston, who has been critical of this celebration, claims that 1988 is the starting date for what she calls the 'event-led economy'. Others began referring to Sydney as the 'City of Spectacle'.

If the [media]defining event of the 1980s was the Bicentennial, the quintessential 1980s place was Sydney's 'other' harbour, Darling Harbour, replete with empty goods yards, railway sheds and wharves falling apart. Under the auspices of yet another authority, the Darling Harbour Authority, this was all given over to the new business of tourism, and turned into a pleasure ground of shopping centre, restaurants and a museum. In Kingston's words, this was 'devised and carried out with ever increasing ruthlessness.' [14]

The [media]biggest celebration in Sydney was the Olympics of 2000, which required the construction of new sporting complexes, primarily at Homebush, where old industrial land surplus to requirements was regenerated in what was trumpeted as the 'green games'. Sydneysiders loved this spectacle, enjoying a few weeks of euphoria, but the direct and indirect costs involved in staging this event have yet to be calculated.

Related to all this is the question of where Sydneysiders congregate to celebrate. All great cities cherish their civic spaces, the public places where collective opinion is expressed and public protest is allowed room for expression. Sydney has no great central meeting place, and the public meeting places are scattered. From the steps of the Sydney Town Hall, many dignitaries have been feted and sports people honoured. The Town Hall itself has witnessed many rallies and protests, and street marches often commence from the adjoining Sydney Square. [15] So too do state funeral marches, following services next door in St Andrew's Cathedral. In recent decades the apron of the Opera House has also become a meeting place, as it is a perfect location to ensure that this signature building locates the place firmly in the global mind as 'Sydney'.

While [media]many suburbs hold ceremonies at their local war memorials on significant days of remembrance, the city's Martin Place with its Cenotaph is the premier ceremonial place for the larger metropolis. Because of its historic proximity to the General Post Office, it was here that the news of world events first arrived in Sydney. It was festooned for the arrival of the USA's Great White Fleet in 1908, it filled with revellers at the ending of various wars, and in recent years giant screens have appeared here to relay the news of significant world or local events. In February 2008 Martin Place acquired a new significance as the place where thousands of Sydneysiders stood in the rain to listen to a long overdue 'sorry' speech to the nation's Indigenous people, from Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in Parliament House, Canberra.

The Domain, once a [media]place where thousands gathered on Sunday afternoons for political soapbox oratory, has in recent decades become a locale for urban parties and rock concerts, while Hyde Park, originally one of Sydney's commons, has long been the scene of celebrations of various kinds. In the nineteenth century, marquees were erected there for balls celebrating royal visits. During World War I its marquees were filled with soldiers being fed. In the early twenty-first century, speakers rallied around the famous Archibald Fountain to protest against the war in Iraq, in front of some of the largest crowds ever seen in Sydney.

One [media]place that has never been considered a public space of value is the forecourt in front of the Customs House at Circular Quay. By rights it should be, given its historical significance as the place where the first settlers staggered ashore to watch the raising of the Union flag and listen to the first governor declare the country for Britain. Nearby the original inhabitants witnessed this invasion of their land. Perhaps it is because in front of the space is a constant reminder of the venality of Sydney's development, in the presence of the Cahill Expressway and Circular Quay railway station, which cut off this space from its place on the shores of Sydney Harbour.

Sydney as cornucopia

There is [media]not one Sydney, and assessments by residents of their own particular part of the whole often differ markedly from the assessments of 'outsiders' living different Sydney lives. A historical overview exposes little stability in the way places are assessed or valued over time, as the changing cycles of fortune of the inner suburbs show. And while some ethnic groups settled in despised localities until they had generated enough wealth to move on to somewhere more prized, other groups colonised and developed suburbs over the long haul. This has been the relationship of Italian immigrants to the suburb of Leichhardt, which they made over and made trendy, and stayed to enjoy.

It is too [media]soon to predict this kind of long-term settling in with more recent groups of new Sydneysiders, although the long-term preference of Vietnamese migrants for Cabramatta may mean that roots have gone down deeply, and the building of significant places for people of Islamic faith, such as the mosques in Lakemba and Auburn, may determine their enduring presence in those areas. Here, the streets are nowadays closed off for major family gatherings and worship at events such as the ending of Ramadan. Chinese temples are similarly the sites of major celebrations and street processions at Chinese New Year. Anyone wanting to experience a cornucopia of culinary tastes, sounds and fashions need only plot a trip through the suburbs of Sydney, to take in the varieties of the world.

Cultural [media]complexity and widespread tolerance has been marketed as one of Sydney's strengths, but there is a dark side to this as well. In the 1990s, while overall wealth grew, there was a sharp increase in wealth segmentation. Growing disparity between the wealthy top, who are participants in the global economy, and the bottom, where unorganised workers are trapped in low-paid jobs, was a portent of potentially destabilised urban cohesion. There is no simple link between recentness of arrival and wealth levels, but there is enough to generate real tensions. There were race riots in Indigenous Redfern in 2004; between teenagers, many of them unemployed, at Macquarie Fields in the south-west in 2005; and at Cronulla at the end of the same year. One of the ugliest confrontations between new and old Sydneysiders in Sydney's history took place on Cronulla beach, traditionally a democratically shared space. On the other hand, many Sydneysiders have passports well stamped with evidence of travels especially in Asia and Europe. And many of those journeys are to go 'home' – to Lebanon, to China, to Italy and so on and on.

City at a crossroads

Sydney is place, it is presence, it is concept. Artists have never stopped using the brush and the shutter lens in an endless quest to capture its essence, to plumb its meanings and, at the banal end of things, to quite simply show it off to the rest of the world. Its novelists and poets have praised it and panned it in more or less equal proportions, with the definitions of what is praiseworthy and what is not changing with the decades, with the perspective, with the wind. At the same time, residents who might sing its praises to the world engage in debate at home over its problems and potentials.

In recent years there has been discussion about the need for urban consolidation, a concept that questions the sacredness of the freestanding family home with its own backyard. At the same time, the backyard has been undermined by the ever-increasing ground-hogging size of dwellings, with the size of new houses doubling between 1993 and 2003. The public space of the high street has been progressively swapped for the private space of the shopping mall since at least the 1960s, and the failure of public transport to keep pace with population growth and spread has led to increasing car dependence and traffic congestion. Some northern beachside suburbs are experiencing the erosion of cliff-faces, and the list of environmental concerns goes on.

Sydney, like all cities, is a work in progress, but for the first time in its history there are some who question the word 'progress'. Cities rise and they fall. In the sustainability stakes, Sydney in the early twenty-first century is again at a crossroads.

References

Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: biography of a city, Random House, Sydney, 1999

Peter Spearritt, Sydney's century: a history, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1999

Shirley Fitzgerald, Sydney: a story of a city, City of Sydney, Sydney, 1999

Notes

[1] Ged Martin (ed), The Founding of Australia: the argument about Australia's origins, Sydney, Hale & Iremonger, 1981

[2] Grace Karskens, The colony: a history of early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009

[3] Marian Quartley, 'Convict History' in Graeme Davison et al, The Oxford Companion to Australian History, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1998, pp 154–56

[4] Shirley Fitzgerald, Sydney 1842–1992, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1992 pp 132–35

[5] Shirley Fitzgerald, Rising Damp, Sydney 1870– 90, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987

[6] John Miller, (pseudonym of William Lane) The Workingman's Paradise, Edwards Dunlop & Co, Sydney, 1892

[7] Shirley Fitzgerald and Christopher Keating, Millers Point: The Urban Village, 2nd edition, Halstead Press, Sydney , 2009, pp 73–94

[8] Max Solling, 'Images of Inner Sydney' in Grandeur & Grit, A History of Glebe, Halstead Press, Sydney, 2007

[9] Christopher Keating, On the Frontier: A Social History of Liverpool, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1996, pp 165–173

[10] Peter Spearritt, The Sydney Harbour Bridge, A Biography, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1982

[11] Denis Winston, Sydney's Great Experiment: The Progress of the Cumberland County Plan, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1957; Paul Ashton, Accidental City, Planning Sydney Since 1788, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1993, chapter 4

[12] Meredith Burgmann and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1998

[13] For example, Evan Whitton, Can of Worms II, Fairfax Library, Sydney, 1987; Tony Reeves, Mr Sin, the Abe Saffron Dossier, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, 2007

[14] Beverly Kingston, A History of New South Wales, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2006, pp 220–249

[15] Margo Beasley, Sydney Town Hall: A social history, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1998

.