The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Chippendale

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Chippendale

[media]Chippendale is an unpretentious little section of the city, wedged between Central Railway Station and the University of Sydney, extending south from Broadway to Cleveland Street. Much of it is covered with nineteenth century workers' terraces and old industrial buildings.

Swamps and gardens

[media]Street names such as Wattle, Rose, Pine and Myrtle hint at a different Chippendale. The area was once densely covered in vegetation, with rich alluvial soil and several creeks that discharged into Blackwattle Swamp. Fresh water and ready food supplies made this an attractive area for the Gadigal people, and also for the Europeans. Early government gardens were established on the northern edge of Chippendale, and the botanical street names are a reminder that in the 1820s, Thomas Shepherd established a successful commercial nursery here. He experimented with viticulture and prospered by landscaping gardens – though not the gardens of Chippendale. Its inhabitants never had such pretensions. [1]

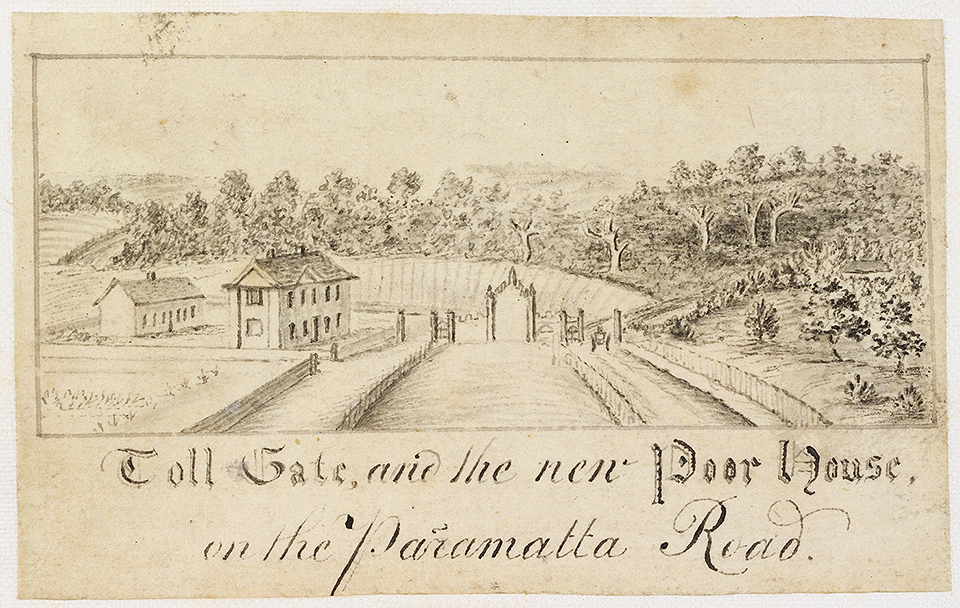

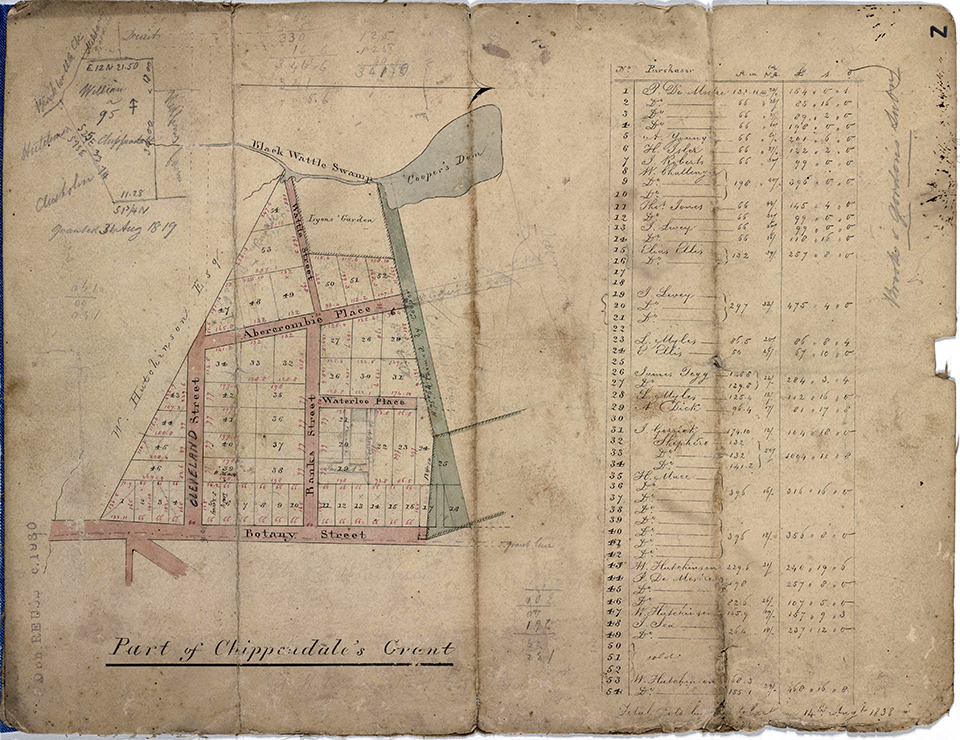

[media]The area takes its name from William Chippendale, who was granted 95 acres (38 hectares) in 1819, although he and his family had been living there for several years before the grant was formalised. At this time the land was beyond the clay pits of Brickfield Hill, past the barracks that housed the convict brick-makers, and past the toll gate at the apex of Pitt and George streets that marked the edge of town. Across Parramatta Street from Chippendale's grant was the undeveloped land of John Harris's Ultimo Estate. Other early colonists who obtained grants inside the boundaries of current day Chippendale were Major George Druitt and Robert Cooper.

Chippendale [media]did a little farming on his holding, but in 1821 he sold it all to Solomon Levey for £380, who in turn sold some and neglected some, so that when he died in 1833, he still held more than 30 acres (12 hectares) of non-subdivided land in Chippendale.

The arrival of industry

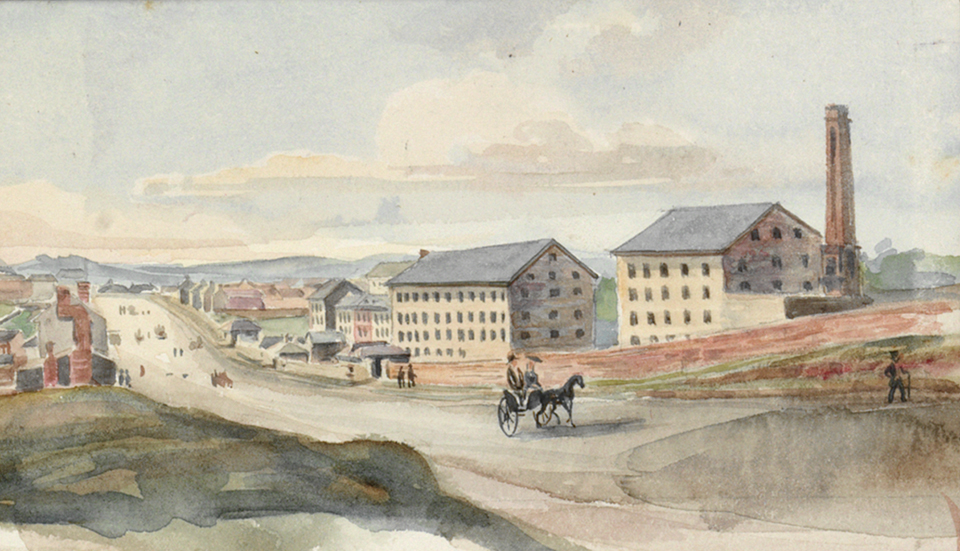

By [media]then the area's industrial future was beginning to emerge. Robert Cooper, who had previously produced gin on Old South Head Road, where his family home Juniper Hall still stands, built a three- and four-storey distillery and factory complex on Parramatta Street, using the fresh water of the Blackwattle stream. Behind the distillery he created a dam which was to figure in the annals of Chippendale for many decades to come. Early recollections of the dam were of gardens and orchards on its banks, of fishing for eels and of aquatic sports, though opinions of the quality of the gin were mixed. [2]

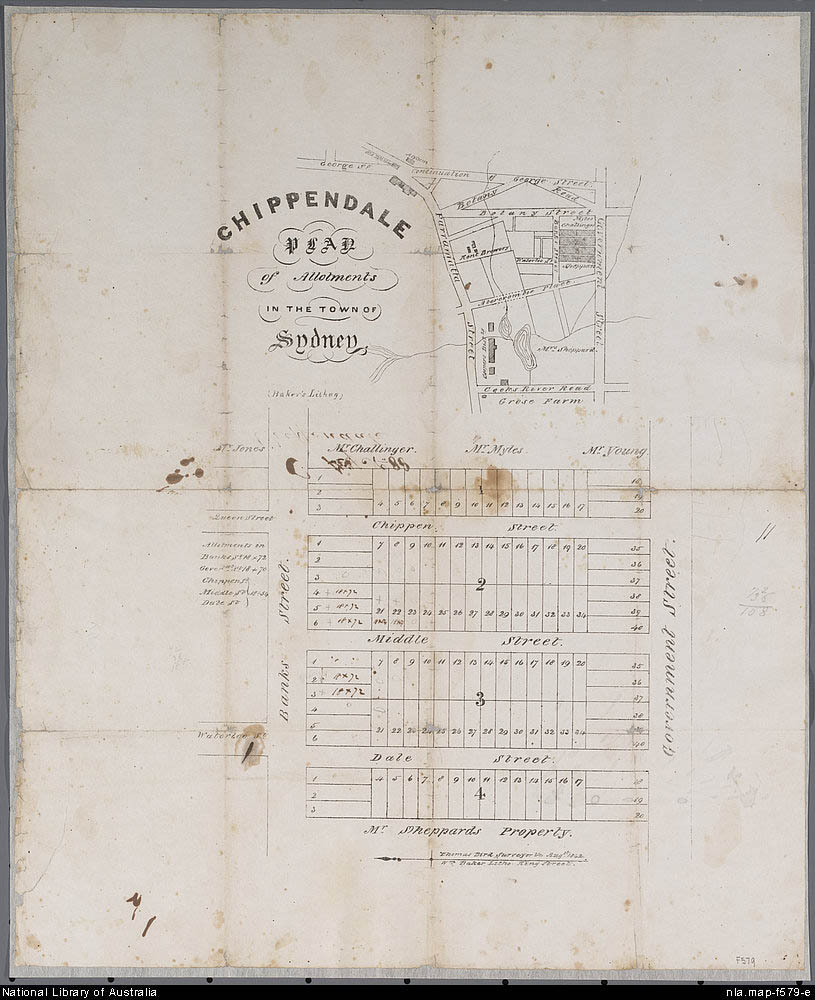

In 1835 John Tooth and Charles Newnham opened their Kent Brewery on land purchased from Druitt's grant, on Parramatta Street, a little closer to town than the distillery. Tooth's brewery grew and prospered for many decades, but finally closed at the beginning of the twenty-first century. By then it was owned by the Carlton and United Brewing Company, but in the understanding and memory of many, the name Chippendale is synonymous with Tooth's beer.

In 1842, Chippendale became part of the newly incorporated City of Sydney. In the 1830s and 1840s an increasing number of narrow streets appeared, providing cramped and substandard housing to Chippendale's working families, especially near Parramatta Street and the headwaters of the Blackwattle swamp. [media]By mid-century there were several medium-sized industrial neighbours, including a flour mill on Abercrombie Street and numerous small establishments on Parramatta Street.

Poverty and community

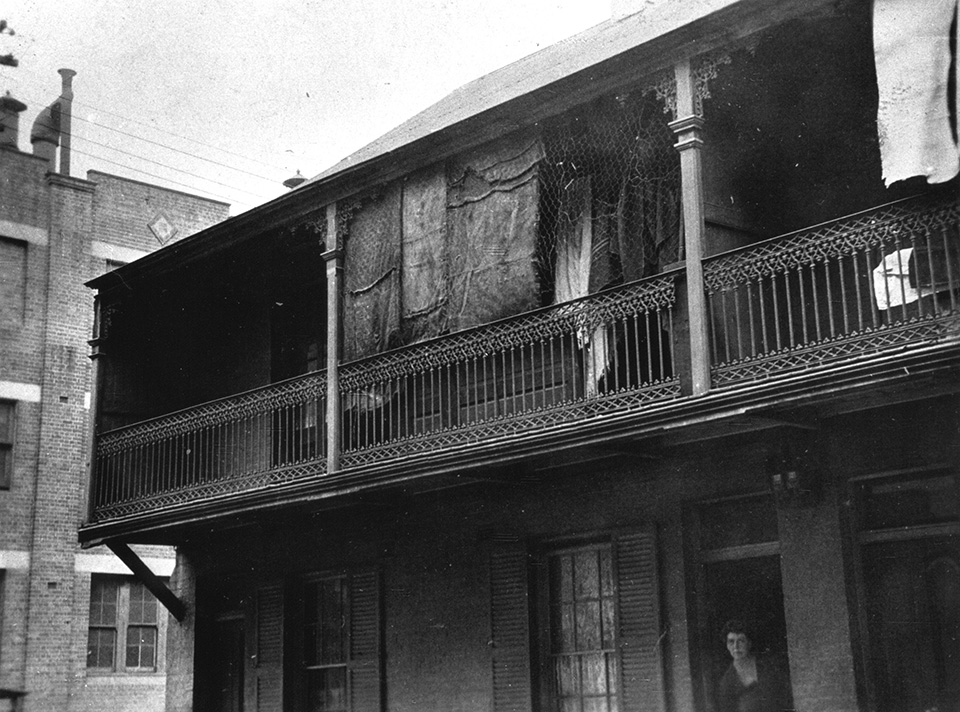

Some of the worst houses were the property of the distiller Cooper, while others were owned by Thomas Broughton, upright citizen, and Mayor in 1847. Rows of wooden barracks-type accommodation were singled out by social commentators for condemnation in the 1850s. WS Jevons's social survey of 1858 described tiny two-roomed cottages as, 'a shocking sight … quite uniform and uniformly abominable throughout'. The following year's Select Committee on the Condition of the Working Classes found many places 'totally unfit' for human habitation.

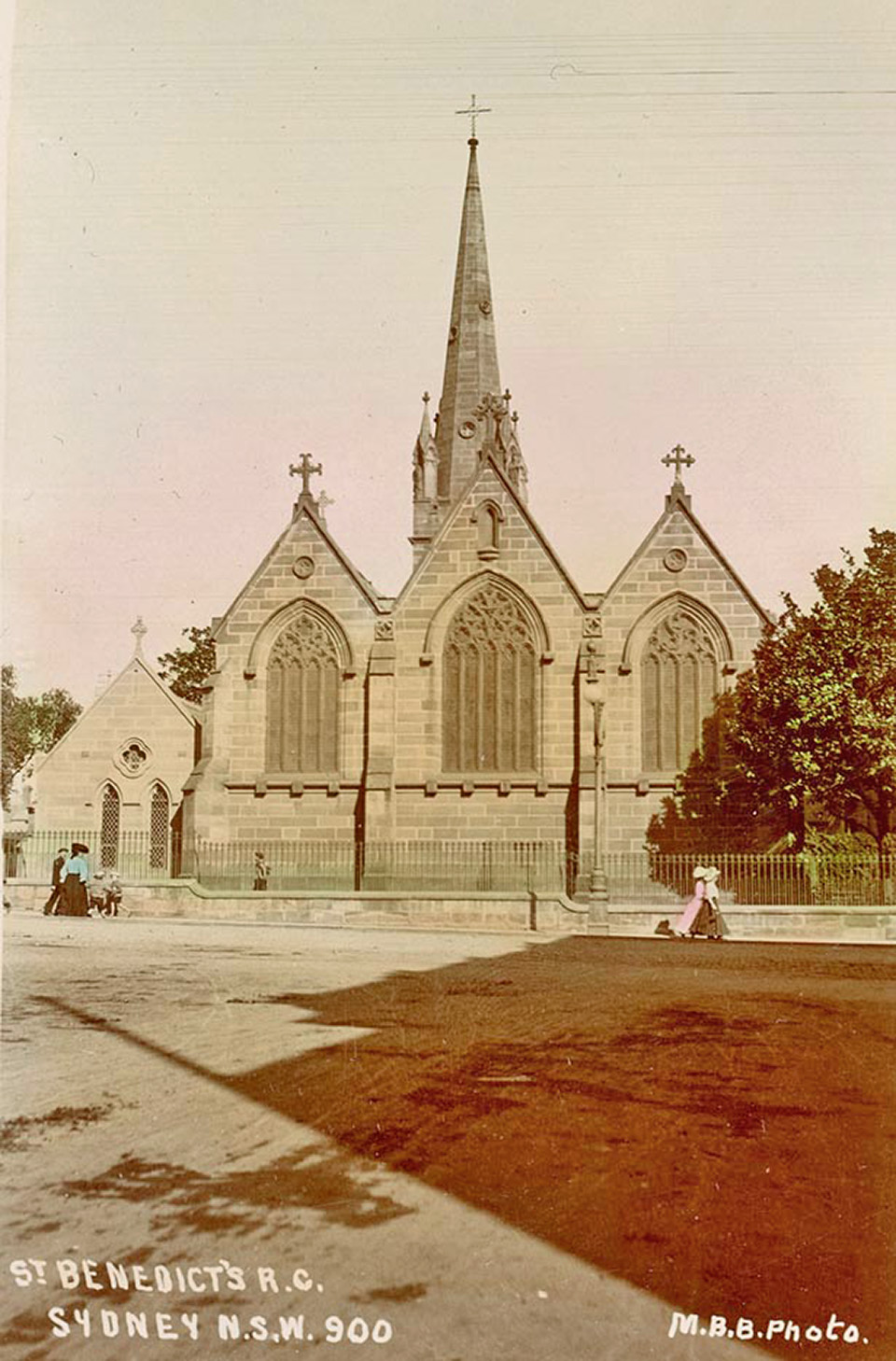

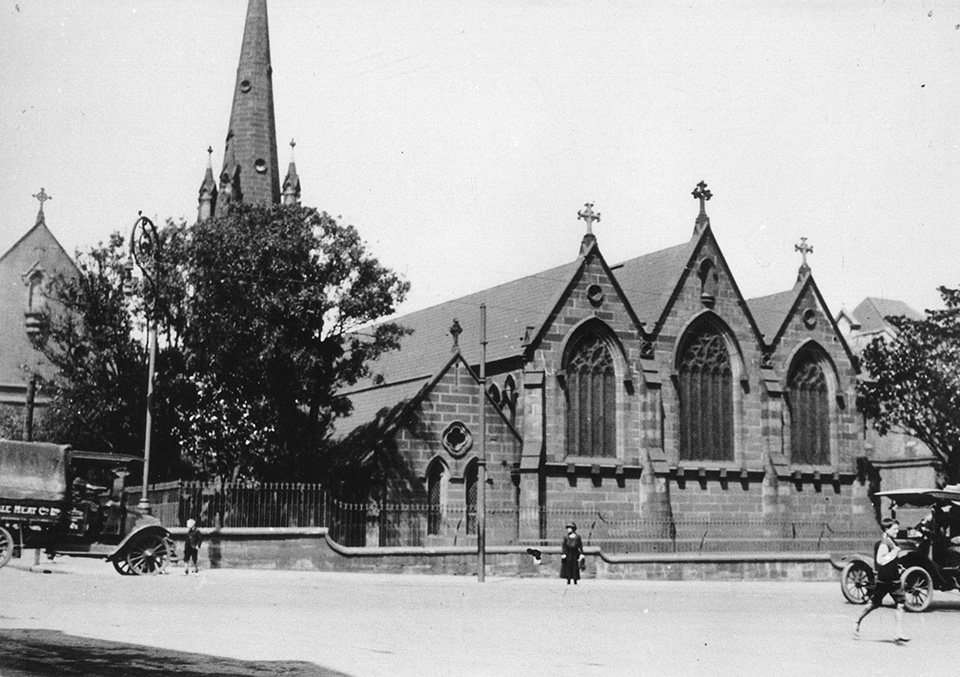

Basic education and religious solace was offered through St Benedict's Chapel and its school house which opened its doors in 1838. [media]Bishop Polding laid the foundation stone for St Benedict's church in 1845. John and Marion Armstrong's Chippendale Academy in Abercrombie Street provided secular education to children whose parents could afford to pay for the daily entrance tickets. A small Wesleyan chapel in Queen Street was replaced by a large building on Botany Road (Regent Street) in 1847, and there were Anglican churches just outside the boundaries – St Barnabas's on Parramatta Street and St Paul's on Cleveland Street. The many public houses on Parramatta Street were augmented by others in neighbouring streets as the settled population of Chippendale grew.

The poor of Chippendale were served by a branch dispensary of Sydney Hospital, established in Regent Street in 1871, and replaced with a purpose-built building in 1926. [media]The Benevolent Society was located just outside its borders, and the Sydney City Mission had a mission in Chippendale at various addresses from the 1870s.

Pollution and drainage

[media]Three significant developments altered the fortunes of Chippendale in the buoyant 1850s – the sale of the Brisbane Distillery to the Australasian Sugar Company in 1852, the opening of Sydney's first railway line in 1856, with its terminal on the city side of the suburb, and the occupation by the University of Sydney of its new buildings at Grose Farm, across Newtown Road (City Road) to the west.

The Sugar Company was reconfigured as the Colonial Sugar Refinery in 1855. It soon set about engaging in the growing Chippendale pastime of demolishing houses in order to enlarge its industrial premises. [media]This enormously successful company offered employment in the area, but the work was often dangerous and unhealthy, while the plant's contribution to local pollution made it unpopular. The burning of bones to create charcoal for its filtration plant was unpleasant, as were the tons of rotting bones that graced its yards. Further, the water from old Cooper's dam, reticulated through the plant for cooling purposes, was at times 'on the nose'. Complaints and petitions from residents to the City Council mounted, and investigations and official reports multiplied. Descriptors such as 'poisonous … intolerable … obnoxious and offensive in the extreme' were common, and there was widespread relief when the refinery decamped to more isolated Pyrmont in 1879. [3]

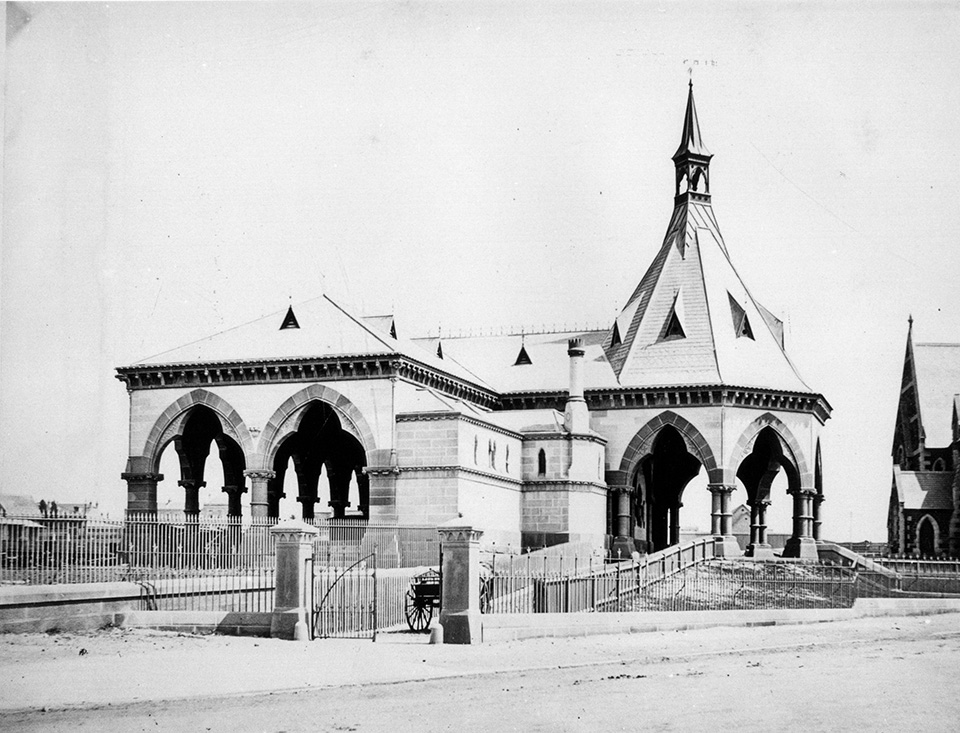

[media]The railways and their locomotive workshops were a second source of pollution, but also a source of employment for thousands of workers in the last decades of the nineteenth century. The development of the Mortuary Station on Regent Street, taking funerals directly to the Rookwood Cemetery, resulted in funeral parlours, monumental masons and florists setting up shop in Chippendale.

By the 1870s all of Chippendale had been subdivided and built over with housing stock that continued to attract official attention for its substandard quality. An 1876 government report commented on some of the same houses that had come in for negative comment back in the 1850s, though some were now mercifully untenanted due to their 'uninhabitable condition'. [4] Closer settlement contributed to increased drainage problems especially in the low-lying land straddling the original Blackwattle Creek. Periodic flooding of houses, with accompanying lawsuits and angry correspondence, went on for decades.

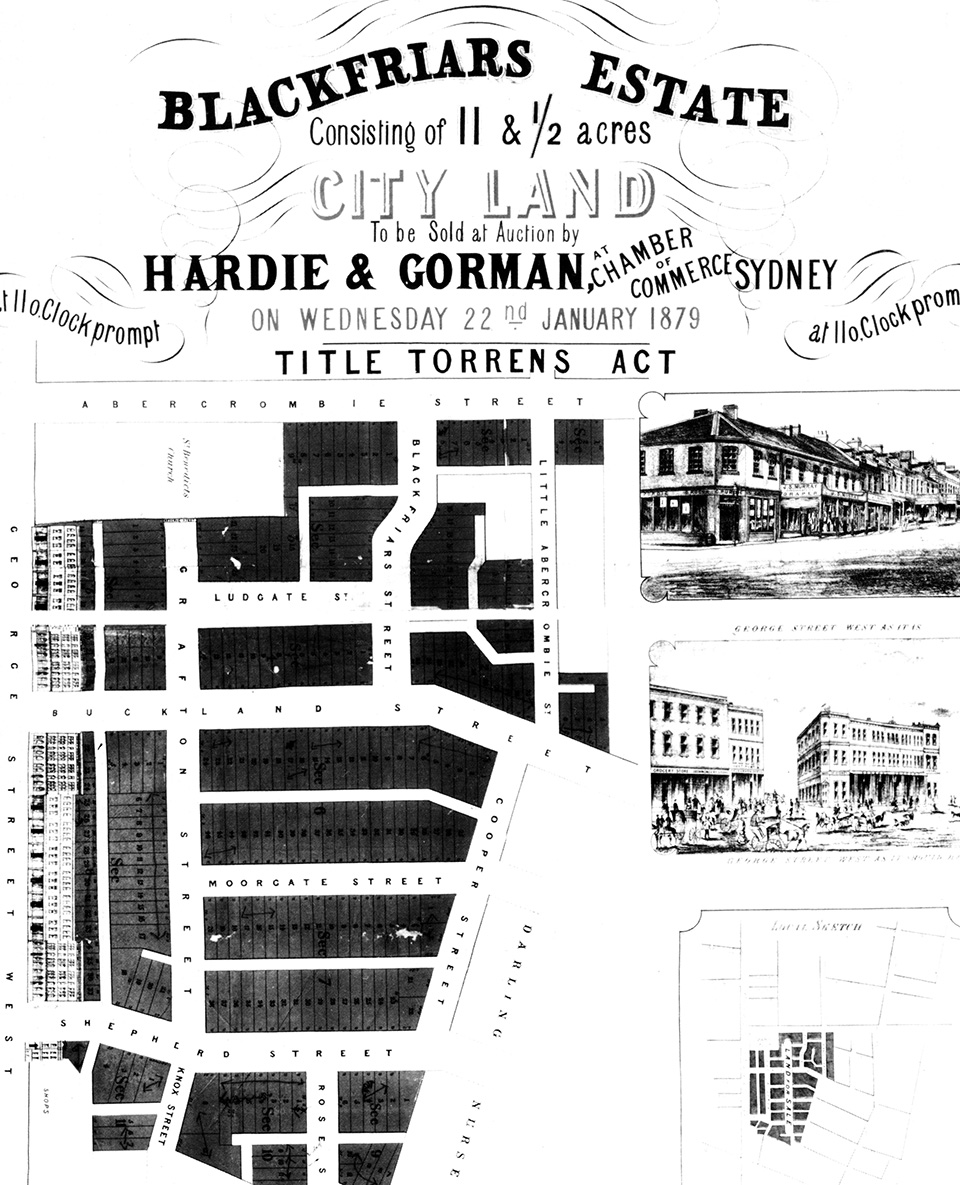

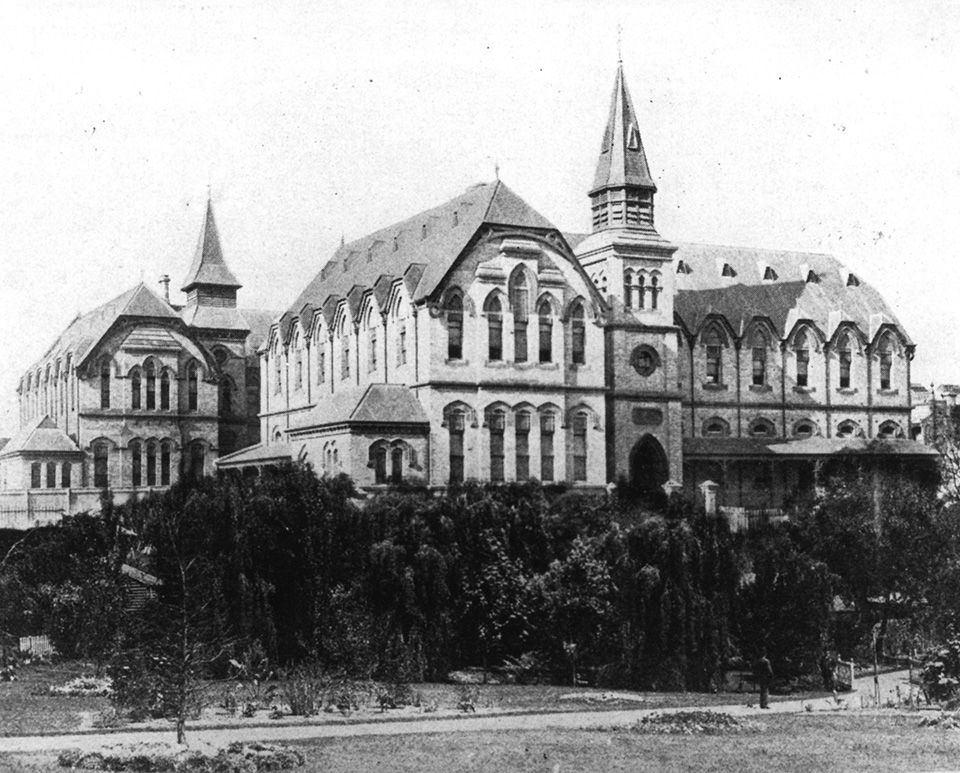

[media]These problems were compounded by the illegal subdivision by Hardie and Gorman of the old Colonial Sugar Refinery site in contravention of new legislation that laid down minimum width of streets in 1879. A decade-long standoff between various authorities commenced. The council would not form the streets or build the drains, on legal advice that to do so would break the law. And in a grand gesture of real estate solidarity, Richardson and Wrench created a similar narrow subdivision on Shepherd's nursery land in 1883. Land sold slowly, and the mean housing that was built was standing in a bog. But the developers had friends in high places. When land sales faltered in 1881, the state resumed part of the land for a school. The choice of this poorly drained site cannot be rationally explained. [media]Neither could the size of the Blackfriars Public School that was built to house 1500 children – far more than the area could sustain. Its construction caused outrage in Catholic circles. [5]

Some of the woes of the subdivision were finally resolved in 1889, after years of parliamentary wrangling, with the passage of an act to 'allow' the council to take over the streets.

Depopulation and change

[media]By the early twentieth century, the population began to fall as factories multiplied. The Wesleyan Church was deconsecrated, and then demolished, while the under-used Blackfriars School was partially given over to the Sydney Teachers College.

[media]Depopulation was assisted by the city council's decision to resume parts of the area fronting Cleveland Street in 1911, demolish the houses, reorganise the streets and sell off the land to industry. A further major resumption occurred along George Street west from 1929 and was not finally completed until the early 1940s. The wider street was renamed Broadway. The most complicated part of this undertaking was deciding what to do with St Benedict's Church. Demolition was rejected in favour of retaining the building, but making it about 16 feet (5 metres) shorter

[media]The factories of Chippendale ranged from bootmaking to food processing to heavier metal-based industries and engineering workshops, and the area produced an enormous range of products. Locals often recalled Chippendale as a series of smells – vanilla if the White Wings factory was having a vanilla baking day, chocolate from the sweet factories, but above all, the cloying smell of fermenting hops from the brewery.

[media]In the Depression of the 1930s many workshops closed or contracted their output, and Chippendale was the site of street battles against the bailiffs and house evictions. Canon Robert Hammond of St Barnabas's Church across Broadway in Ultimo set up one of several Hammond Hotels in a factory in Buckland Street, offering sustenance and skills help the unemployed find work. It had beds for 30, but often fed as many as 300 a day in its makeshift dining room. St Barnabas's down-to-earth self-help quasi-religious billboard messages on Broadway, which were later echoed through cheeky replies posted on the hotel opposite, became a long-term Sydney landmark.

[media]And so Chippendale remained an unloved and unremarkable piece of Sydney's working-class industrial landscape for many decades. By mid-century its Anglo-Celtic population was joined by Italians and Greeks, while later the Lebanese, then Vietnamese found their way to its factories and workshops.

Remaking Chippendale

As industries moved away from the inner city areas in the second half of the twentieth century, Chippendale became one of the first places where factories and warehouses were converted into residential accommodation. By the 1970s, the area was attracting young, well-educated people, often associated with the University of Sydney and other tertiary education institutions. Blackfriars School became part of the University of Technology, Sydney in 1996 and the old St Benedict's school was reinvented in 2004 as the University of Notre Dame Australia. Old workers' pubs got facelifts and trendy beer-gardens. Parts of Chippendale were heritage listed. Gritty little art galleries, studios and organisations dedicated to social change moved in along with the students and academics, and by the time of the 2001 census the population was not only increasing, but was significantly younger and better educated than the Sydney average.

[media]This renewal took place beside the ongoing expansion of Chippendale's most tenacious industrial stayer, the brewery, which was still expanding its landholdings in the early 1990s. But the writing was on the brewery wall, and the developers were circling what would become one of the largest parcels of land to be released onto the inner Sydney market for a long time. In 2008, demolition of the buildings began, amid controversy about the planned new development.

Though its underlying water-courses are largely tamed, the occasional flood still reminds of earlier times. [media]So do the healthy eucalypts and angophoras that line Chippendale's narrow streets, fed by the fertile soils laid down in the old Blackwattle swamp. Current battles over the type and quality of development on the brewery site echo earlier nineteenth century real estate sagas. Chippendale is, as ever, being remade.

References

Shirley Fitzgerald, Chippendale, Beneath the Factory Wall, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1990

Notes

[1] James Broadbent 'The Push East…' in Max Kelly, (ed), Sydney, City of Suburbs, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1987, p 21

[2] Old Chum, (J M Forde), in 'Old Sydney', Truth , 12 June 1910, 26 June 1910

[3] Shirley Fitzgerald, Chippendale, Beneath the Factory Wall, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1990, pp 35–44

[4] 'Sydney City and Suburban Sewage and Health Board, NSW Legislative Assembly, Votes and Proceedings, 1875–6, vol 5, p 611

[5] Shirley Fitzgerald, Chippendale, Beneath the Factory Wall, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1990, pp 53–64

.