The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Glebe Coroner's Court

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

[media]WARNING: This article contains details of the recent history of the Coroner’s Court, including past cases. This content may be disturbing to some readers.

Glebe Coroner's Court

‘Inquests are most fantastic, the most granular, the most tragic, the most historically insightful because the way in which people die is a fascinating way to explore how people lived’ – Gideon Haigh.[1]

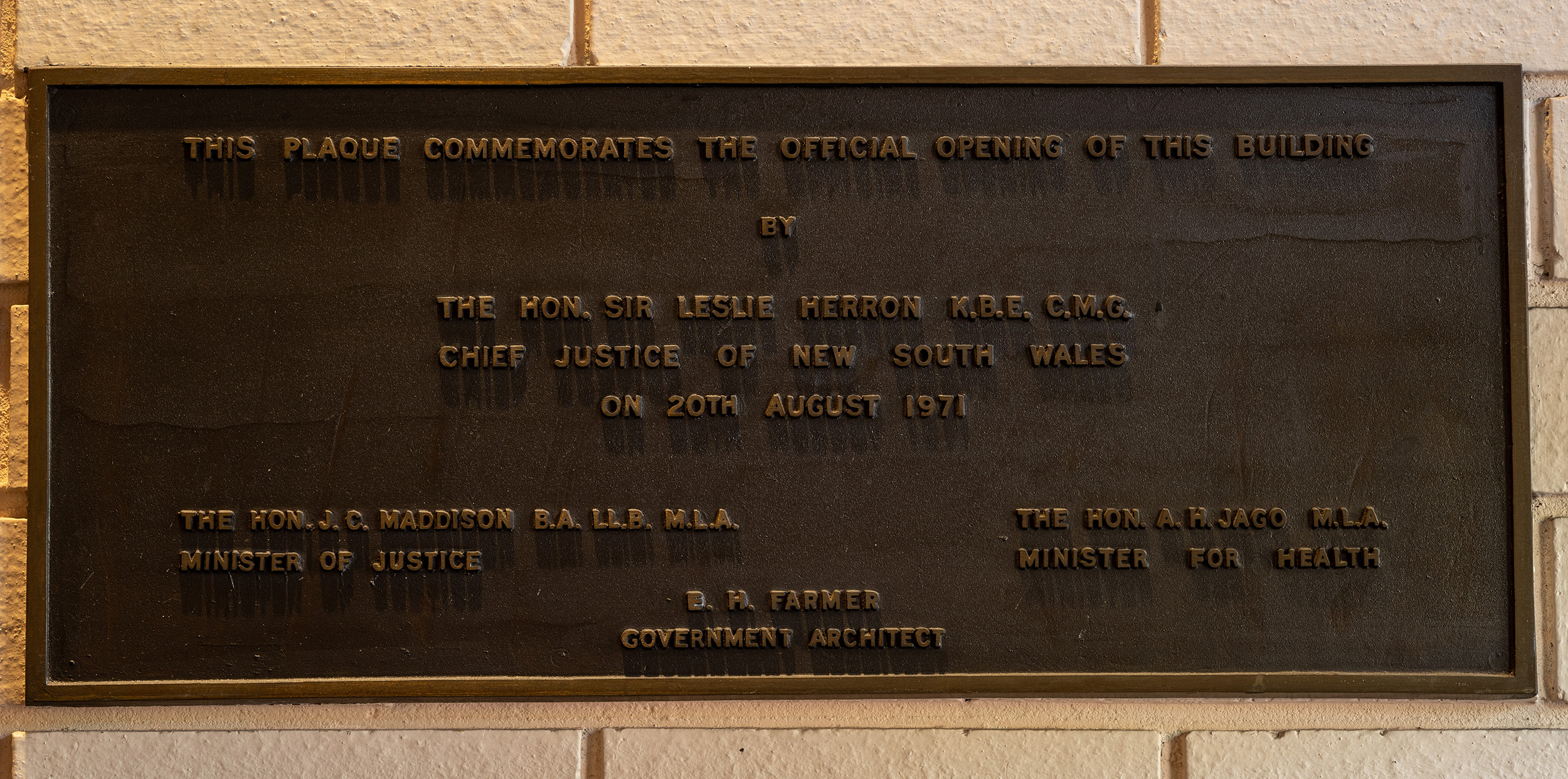

[media]Tens of thousands of Sydney’s unexplained deaths, accidents, fires, explosions and missing persons were investigated at the former NSW State Coroner’s Court in Glebe. The former NSW State Coroner’s Court and Morgue building was located at 44–46 Parramatta Road, Glebe for 48 years. The building functioned as the centre of coronial justice in the state, housing three coroner’s courts and offices on the top floor and the morgue, refrigeration room and laboratory on the bottom floor. The Coroner’s Court building also housed the Department of Forensic Medicine since 1971. In December 2018, a new facility housing both the Coroner’s Court and what is now known as the NSW Health Pathology Forensic Medicine service was officially opened in Lidcombe. Forensic Medicine began its work in Lidcombe in February 2019.

[media]The role of the Coroner, as of the Coroner’s Act 2009, is to:

investigate certain kinds of deaths or suspected deaths in order to determine the identities of the deceased persons, the times and dates of their deaths and the manner and cause of their deaths, and to enable coroners to investigate fires and explosions that destroy or damage property within the State in order to determine the causes and origins of (and in some cases, the general circumstances concerning) such fires and explosions.[2]

[media]The manner of death classifies how the injury or disease process caused a person’s death and includes five categories: natural death, homicide, suicide, accident and undetermined. The cause of death is the specific injury or disease process that leads to a person’s death.

Approximately 6000 deaths are reported to the NSW coroner each year, including 3000 occurring within the Sydney metropolitan area.[3] Each death investigated by the coroner involves unique intricacies and issues, yet every death is also a human tragedy, laden with emotion and bereavement. As the third coroner’s court in Sydney, the Glebe Coroner’s Court saw countless investigations and inquests throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Through its function as the centre for a series of major investigations, it came to represent both trauma and justice within the community.

The office of the coroner

[media]The office of the coroner in New South Wales is older than the state itself. Governor Arthur Phillip was granted the powers to ‘constitute and appoint justices of the peace, coroners, constable and other necessary officers’ on 2 April 1787, mere weeks before he embarked on the long journey to Australia aboard the First Fleet.[4] These powers broadly reflected contemporary British laws on coronial matters. Like their British counterparts, coroners in the early colony were required to look into ‘sudden or unnatural deaths’ within their particular districts, accompanied by a twelve-man jury.[5] Gathering twelve willing men from a population of a few thousand was often a difficult task for the coroner; the requirement was often almost impossible to meet in rural areas during the nineteenth century.[6]

As the colony evolved, coroners were appointed for various jurisdictions within Sydney's districts and the regions. Artist John Lewin was selected by Governor Lachlan Macquarie as the coroner for both the town of Sydney and the County of Cumberland in October 1810 and served until his unexpected death in 1819. His successor, harbourmaster George Panton, served as coroner of the Country of Cumberland for only two months before taking the role of Postmaster for New South Wales, and in November 1819 his replacement Edward Smith Hall was appointed as coroner of the entire territory of New South Wales. When Hall resigned in October 1821, the Colonial Secretary’s Office announced the appointment of George Milner Slade as the official coroner for the Sydney region.[7] Slade had arrived in Sydney as a free settler in 1819[8] after avoiding a court-martial for misappropriation of funds during his army service in Jamaica.[9] At the time, no official headquarters had been constructed for the coroner, and Slade’s salary included compensation for travel around the metropolitan district.

Coronial investigations also played a critical part in validating the credentials of medical practitioners in New South Wales, well ahead of requirements in Britain, thanks to the Medical Witnesses at Inquests Act 1838.[10]

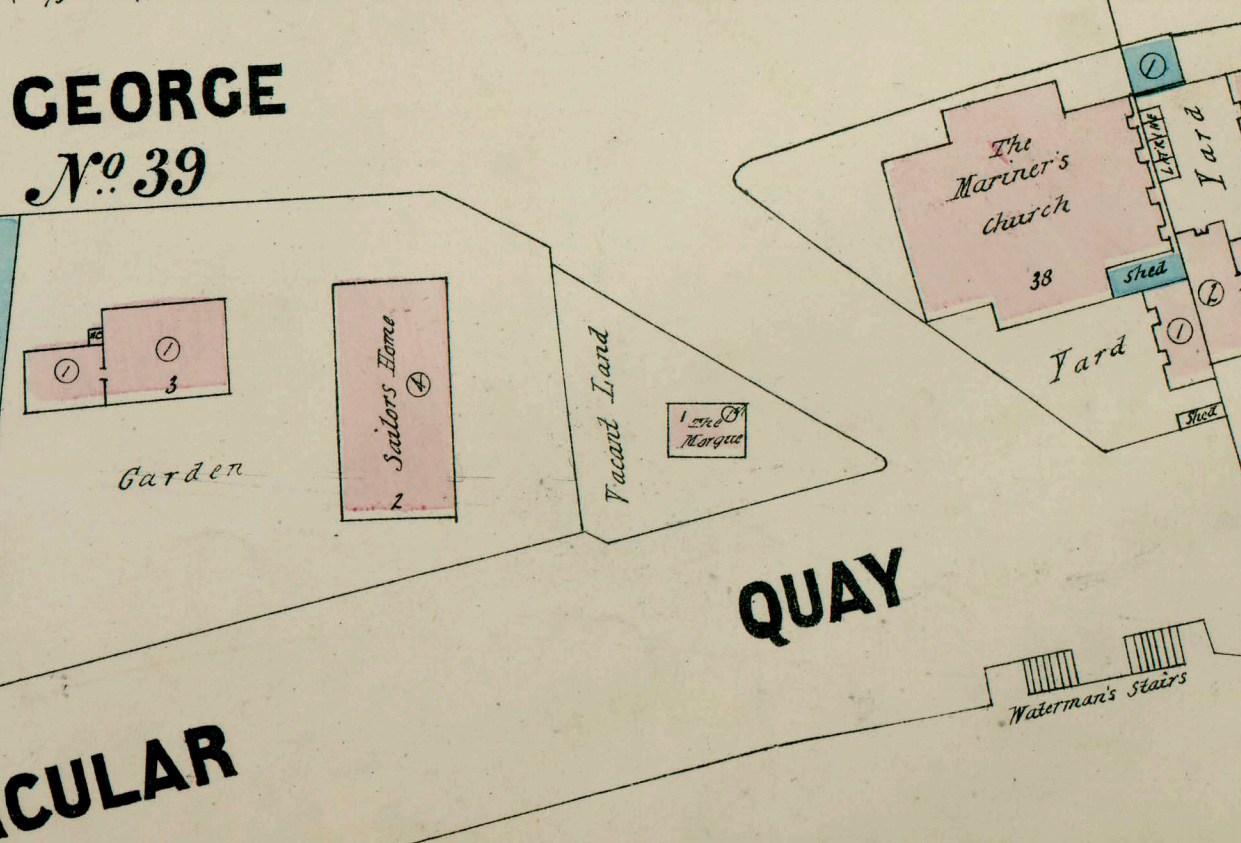

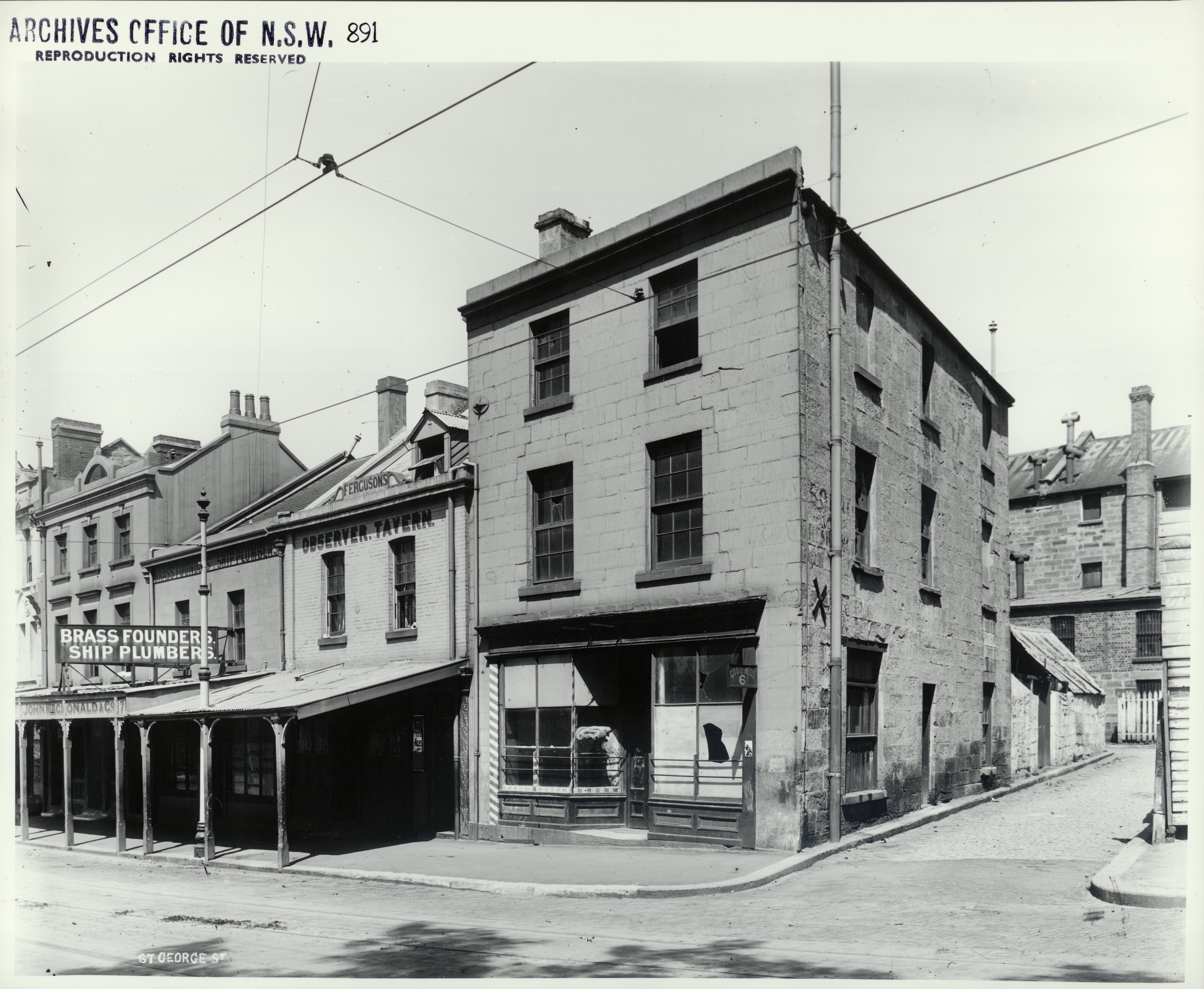

The first and second Coroner’s Courts

[media]The first formalised Coroner’s Court building came during the late stage of John Ryan Brenan’s 20-year stint as coroner. In June 1853, Brenan floated the idea of constructing a Dead House (or morgue) near Cadman’s Cottage in Circular Quay. The building was designed by Colonial Architect William Weaver, and built by Thomas Coghlan. Both Weaver and Coghlan’s careers plummeted during the construction of the morgue, with Weaver resigning over financial issues and Coghlan prosecuted by the Crown for falsifying work hours. The completed Coroner’s Court, also known as the North Sydney Morgue, was little more than ‘a room with a table on it’, as later noted by a disgruntled coroner, with space for only two bodies. If other cadavers were present, jury members would have to step over them; the only place for more than two bodies was on the floor.[11] [media]The stench of decomposing corpses was often unbearable for the jury members, with inquests more commonly held at the lodgings of the deceased or in more appealing taverns such as the Observer Tavern at The Rocks.[12] The returns from interested patrons and thirsty jury members was an inviting prospect for local publicans, with journalist JM Forde reporting in The Truth that ‘weeping friends can wet eye and whistle while awaiting coronial pleasure’.[13]

The Dead House in Circular Quay remained in operation until the resumption of The Rocks at the turn of the 20th century. The building was so dilapidated by 1901 that the Evening News referred to it as ‘the old tin shed at the Circular Quay’.[14]

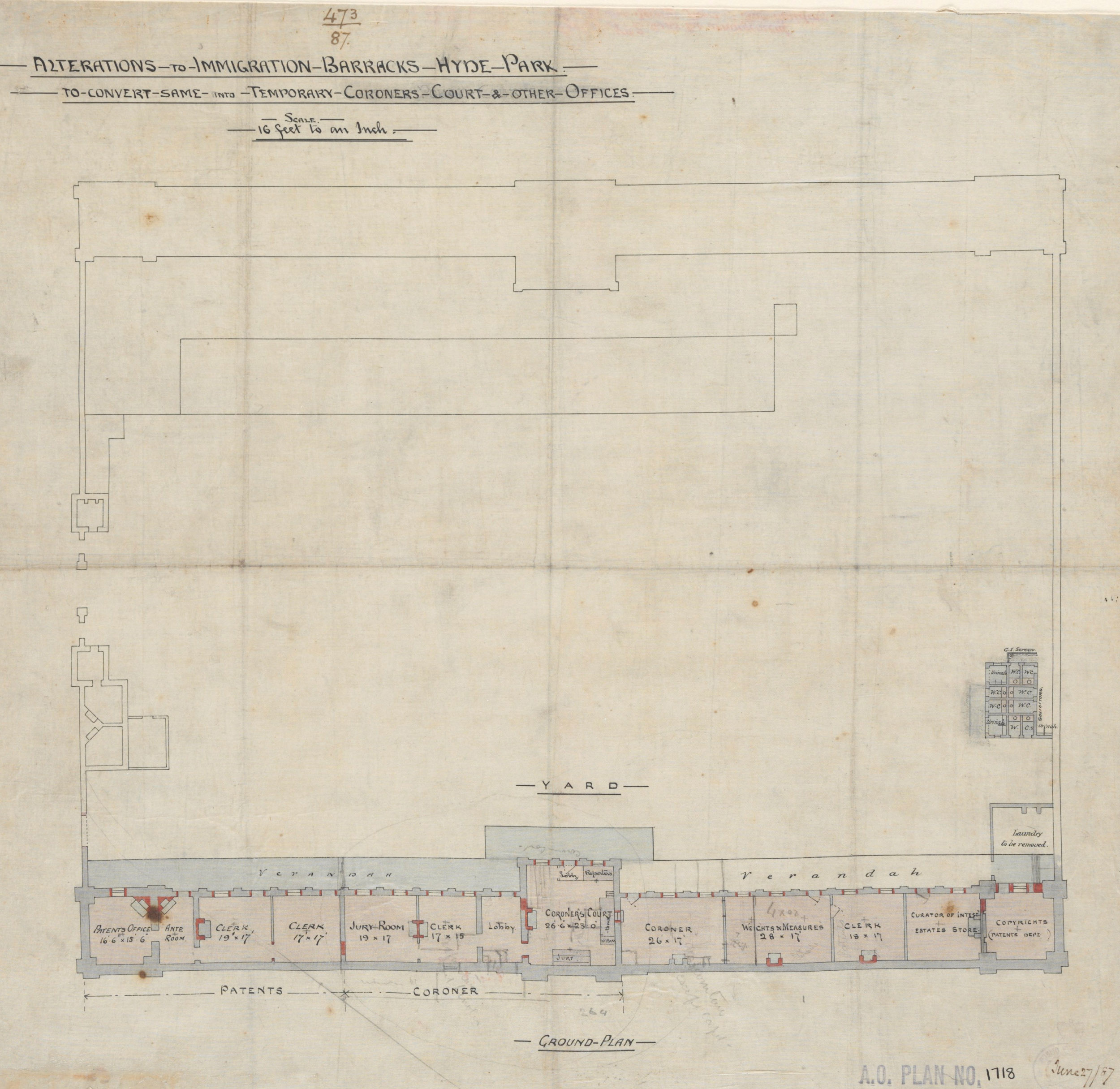

[media]The Coroner’s Court itself moved to various locations during the late 19th century. Twice it was housed within the precincts of Hyde Park Barracks, with a brief stint at Lower Fort Street in Millers Point in the mid-1880s under coroner Henry Shiell.[15] During these shifts, the role of the coroner was also evolving away from its British antecedents. In 1861 a colonial Act was passed ‘to empower Coroners to hold Inquests concerning fires’, as well as the power to grant bail to people charged with manslaughter as part of an inquest.[16] By the mid-1880s, Shiell’s caseload included 600 cases of unexplained deaths and fires per year.[17]

[media]Another Act passed in 1898 granted more extensive rights to medical witnesses during the inquest process, including the entitlement to one guinea for their attendance, two guineas for conducting an autopsy and travel reimbursements if the doctor lived more than ten miles from the site of the inquest.[18] From 1898, coroners could also formally charge a person suspected of arson, murder or manslaughter. The 1901 Coroners Act gave local coroners two intriguing extra powers; the legal power of a justice of the peace and the right to hold an inquest on a Sunday.[19] This disturbance of the Sabbath was likely an unpopular choice with jurors.

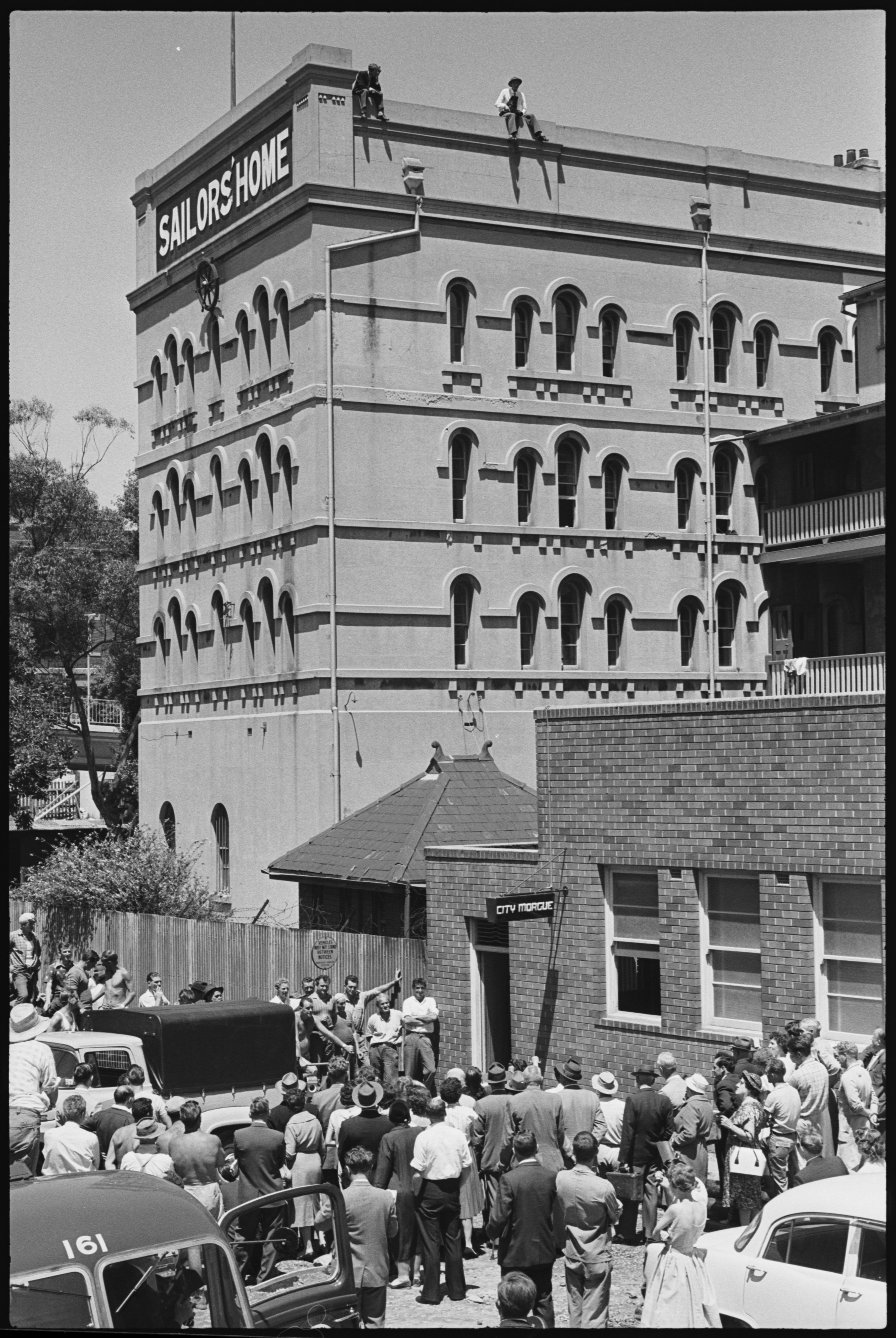

[media]Following the closure of the Dead House associated with the Devonshire Street Cemetery in 1901, the North Sydney Morgue was demolished and designs submitted for a new facility in the same location.[20] The new Dead House and Coroner’s Court was constructed from dark brick with a sandstone trim, with a glass-walled room available for viewing bodies and a dedicated laboratory. The court also provided separate waiting rooms for male and female witnesses. This second Coroner’s Court was completed in 1908 to the tune of £4235. Another Coroners Act was passed four years later, providing sweeping changes ‘to consolidate the enactments relating to Coroners inquests, and to magisterial inquiries into the cause of death’.[21] The most important development of this act was the eradication of the jury, enabling the coroner to rule alone during a coronial inquest. The first coroner to sit under this act was Henry Storry Hawkins.

[media]During the early 20th century, post-mortem examinations became a key part of how inquests were investigated. The chief medical officer of the time was Dr Arthur A Palmer, whose vast experience earned him the nickname ‘The Post-Mortem King’ in 1925.[22] The ‘modern’ facilities of the 1908 Coroner’s Court had become outdated by the 1930s, with the location of the facility in Circular Quay a point of tension in the community. In 1936, the captain of the P&O cruise ship Strathaird protested that his passengers had a direct sight line to the post-mortem room, a rather appalling introduction to Sydney Harbour.[23] Any plans to improve the court were put on hold during World War II, with additions and alterations finally made in 1947. This included the first instance of a refrigerated room for body storage.

[media]By the 1960s, the science of forensic medicine was giving new insights into the human body. Unfortunately for Sydneysiders, however, laboratories with modern technology for forensic pathologists had yet to arrive in the city. The Division of Forensic Medicine, a specialist division within the Department of Public Health, was established in Sydney in 1961.[24] The division employed specially trained forensic pathologists, who were empowered to perform post-mortem examinations on any bodies under the jurisdiction of the coroner, visit the scenes of crimes to assist police and provide training to medical practitioners.[25]

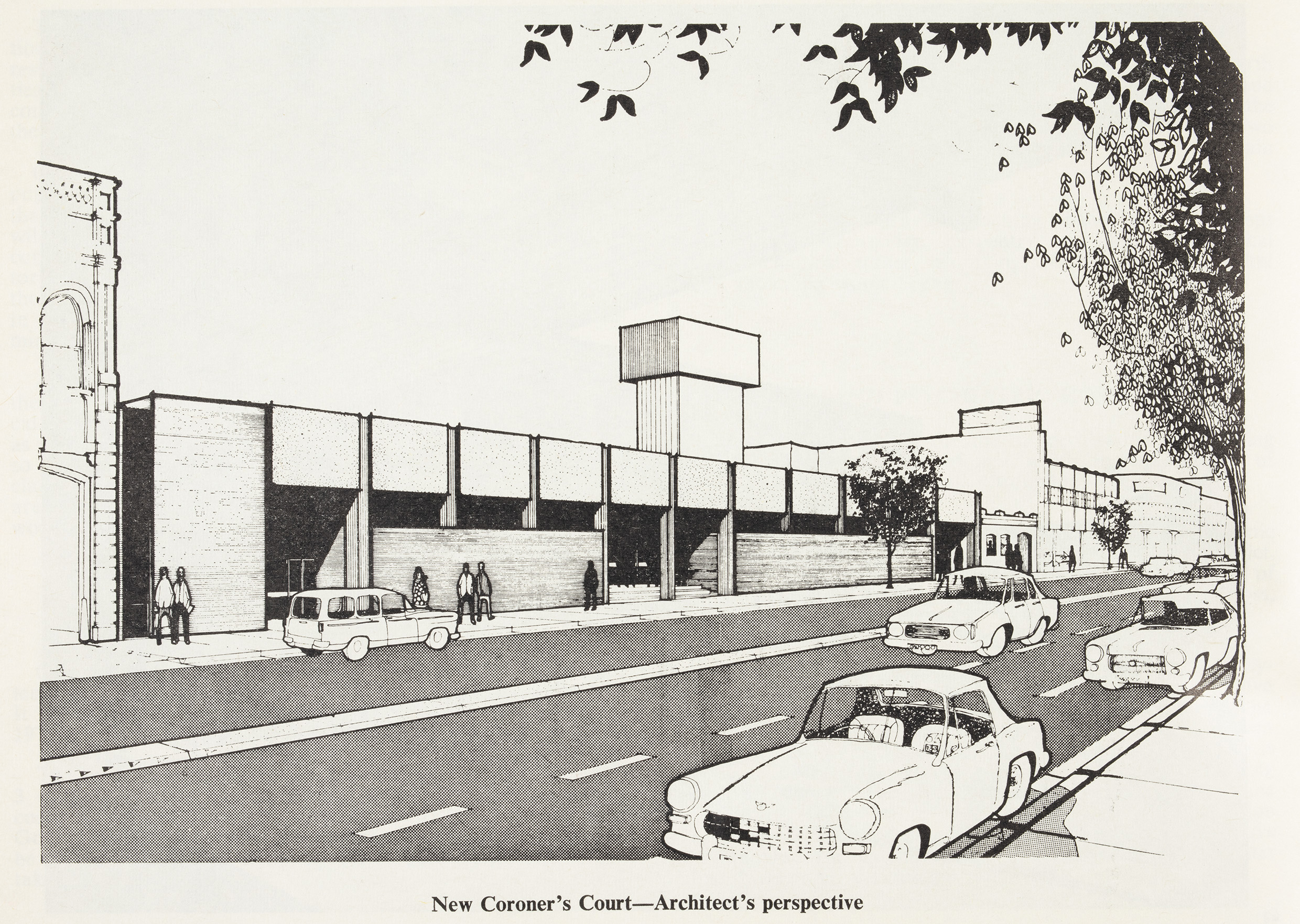

To better serve the growing Sydney community, the Coroner’s Court and the Division of Forensic Medicine needed a new facility better equipped to handle the legal and forensic complexities of coronial inquests in the modern age. A location opposite the University of Sydney on the busy Parramatta Road was chosen for the new building. It occupied a site originally used as the GH Olding coach-maker’s workshop.[26] Construction began on a new two-storey court building in 1968, and the Glebe Coroner’s Court was officially opened in 1971.

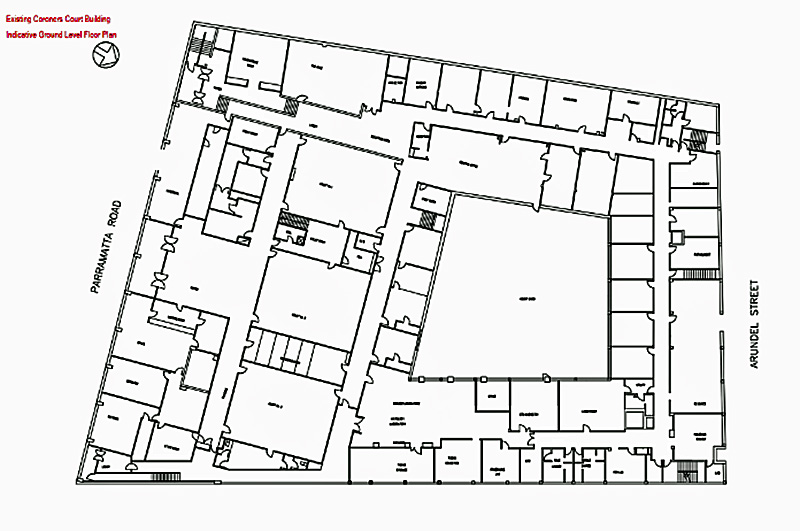

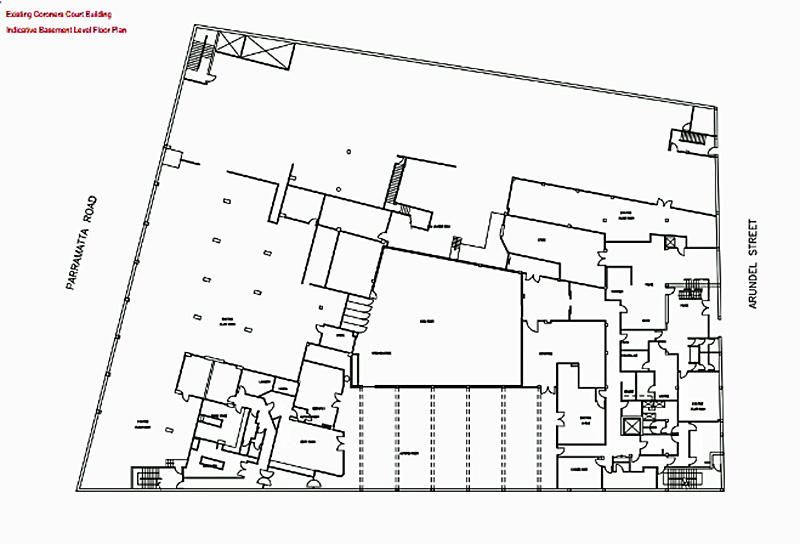

The Coroner's Court building

[media]The Glebe Coroner’s Court was divided into two floors, with the top floor comprising the public court and administrative section, and the bottom floor consisting of the morgue post-mortem examination room, laboratories and loading zone. The top floor was built around a central courtyard, with a single corridor connecting all rooms on the floor. The State and Deputy Coroners, Crown Solicitors, Coronial Advocates, registrars, officers in charge (police officers overseeing a particular case), court clerks, counsellors and administration staff occupied the top floor. Members of the public, the press and expert and non-expert witnesses were also allowed access to this level. The top floor furthermore housed extra laboratories, including the tissue storage, molecular biology and histopathology labs, alongside the offices of senior forensic pathologists. The bottom floor was the turf of the forensic pathologists, technicians and assistants who cared for and investigated the deceased. Family members and next-of-kin of the deceased were able to enter the morgue to view the body, often accompanied by a counsellor for support.

[media]Though all precautions were taken to separate the two floors and their various functions, occasionally the two worlds collided with memorable results. In July 1973, the courtrooms had to be evacuated due to a strong smell coming from the morgue below, after an air-conditioning malfunction caused foul air to be diverted into the courtroom.[27][media]

Complexity and emotion – the courts

[media]The courtrooms are the public face of the NSW Coroner’s Court, where inquests and inquiries take place. An inquest is a formal investigation by the coroner into a death or suspected death, including missing persons. Also undertaken by the coroner, an inquiry is the formal investigation of a fire or major incident such as an air crash or explosion.[28] These legal processes can last weeks, months or even years depending on the complexity of each case. At the conclusion of an inquest or inquiry, the coroner in charge of the case makes a ‘finding’, a written document which states the narrative of death or disaster, plus any decisions or recommendations associated with the case.[29] The coroner can also return an open finding, meaning that the manner of death cannot be determined.[30] If the family of the deceased is unhappy with the findings, they can appeal the inquest or ask for further detail, which the coroner is legally required to answer.[31] The role necessitates compassion and understanding as well as a sharp legal mind.

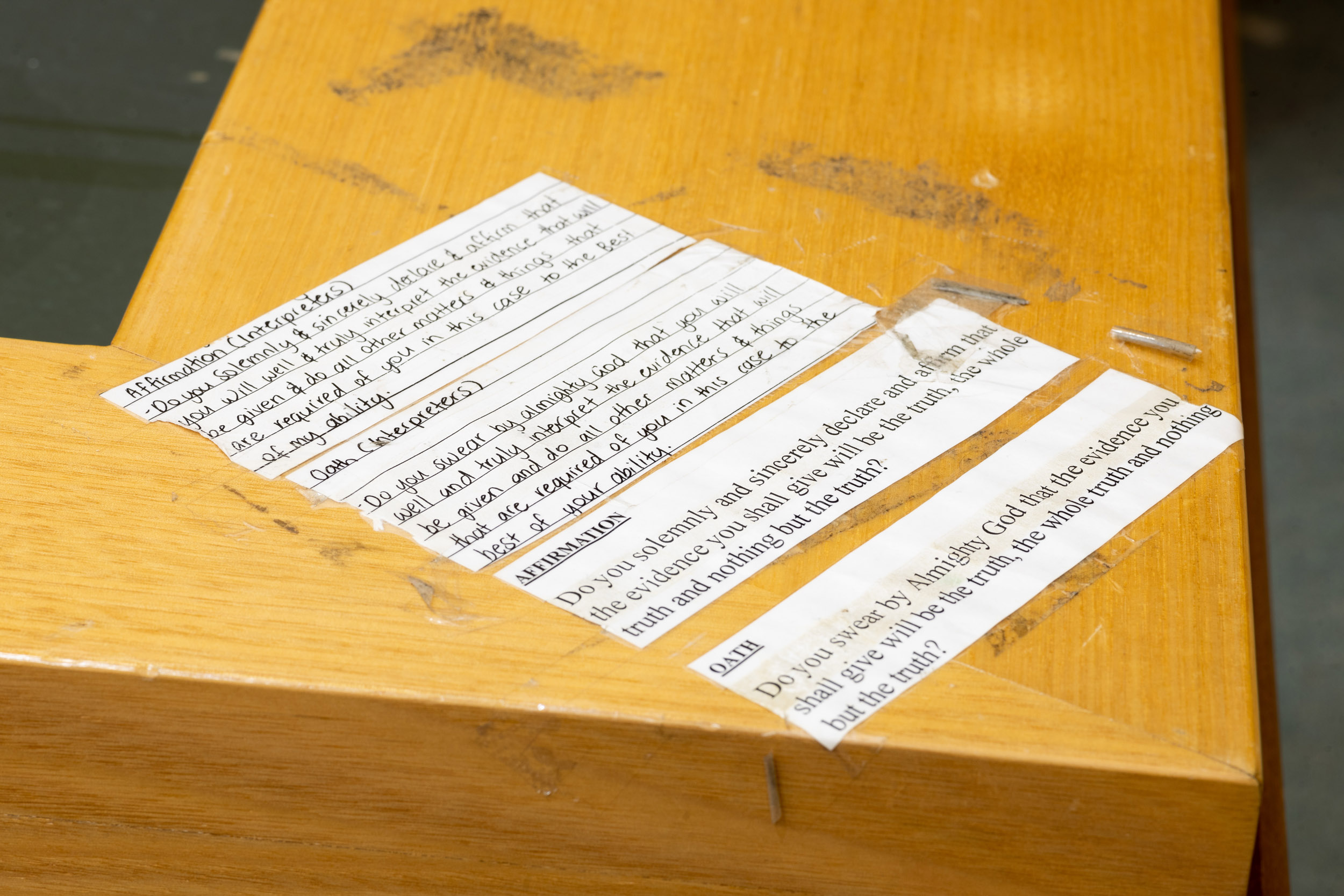

[media]The main areas of the Glebe Coroner’s Court accessible to the public were the three courtrooms, which were identical in size and panelled in blonde wood. During an inquest or inquiry, the coroner in charge would wear a black robe and sit at the high bench, able to look out over the entire courtroom. The legal assistants of the coroner, the court monitor and court officer, sat in front of the coroner to record the proceedings and handle documents. At the same level, in a separate wooden box, stood the witnesses. The task of a witness was not an enviable one, with the court allowing as much support to the person as possible. A support person or counsellor was permitted in the witness box alongside the witness, but could not speak for them.[32] If an interpreter was necessary, they also stood in the box to assist the witness with swearing in and answering questions. During a coronial inquest, the witness could swear either an oath on a Bible or relevant religious text, or provide an affirmation, which requires no religious text.

[media]Facing the bench and the witness stand was a long table of blonde wood, where any lawyers employed by interested parties and the counsel assisting the coroner sat. The counsel assisting was usually a Coronial Advocate (a specially trained plain-clothes police officer) or in especially complicated cases, a representative from the Crown Solicitor’s Office. Their job, aptly described by the title, was to assist the coroner. The coroner, the counsel assisting and the lawyers could all ask questions of the witness during an inquest. Surprisingly, family members were also able to question witnesses, either by electing a family representative, or through a lawyer or the counsel assisting. Family members could also apply to directly address the court about their loved one, though it was not possible to speak personally to the coroner.[33]

In the back of the courtroom was the public gallery, where interested parties and family could watch the procedure without interruption. The media could also attend inquests and inquiries, usually seated in the public gallery. In certain cases, the coroner had the right to close the inquest, barring the media from the courtroom.

Forensics and farewells – life and death in the morgue

[media] The morgue area was accessed through a back door or could be entered from a staircase off the courts. This was the more private section of the Coroner’s Court building, able to be accessed by staff, counsellors and occasionally by family members and loved ones of the deceased. Bodies were transported from ambulances on gurneys, with a special loading dock lifting the gurney from the vehicle to the morgue entrance. The bodies would then enter the largest area on this floor, the refrigeration room, which comprised almost a quarter of the total morgue area.[media]

[media]The refrigeration room could store around 200 deceased people, which were placed on gurneys or pull-out slabs in a triple shelf. The refrigeration room was attached to two post-mortem spaces: a larger industrial-style space with multiple autopsy tables and a smaller viewing/post-mortem room. The small room featured a glass wall that opened out onto a theatre space, from which family members could identify bodies or medical students could watch presentations. The majority of bodies admitted to the Forensic Medicine service required a post-mortem examination to assist with the determination of the cause and manner of death. During a post-mortem, all parts of the body underwent a detailed examination by a forensic pathologist, with small tissue samples taken and subjected to various tests. These tissue samples were usually retained onsite, in case new evidence could be uncovered with future technological advances. In some cases, whole organs were kept for extensive testing for disease and damage.[34] Once an investigation was completed, the coroner would approve the respectful repatriation of the organs following careful consultation with the bereaved family. The results of all tests were passed directly to the coroner overseeing each case, often playing a large part in determining a fair verdict in a coronial inquest. After the post-mortem was completed, the coroner released the body to the family.[35]

[media]The morgue section of the building was updated continuously with new technology, although the clunky gadgets of the 1960s and 1970s were also largely retained. These developments led to a peculiar mix of old and new devices throughout the morgue, with plasma screens and DVD players placed alongside decidedly retro consoles. A positive effect of new technology was that forensic pathologists could process autopsies less intrusively, a development welcomed by family members of the deceased. In 2015, the Forensic Medicine service began using CT scanning. This allows forensic pathologists to use detailed CT images of bones, tissue and organs to determine the cause of death in the least invasive manner possible (in keeping with the updated Coroners Act).

[media]Despite being surrounded by the dead, the mood of morgue staff was determinedly cheerful. Forensic pathologists and post-mortem assistants would often play music on a radio or sit quietly in the staffroom following a post-mortem.[36] A height chart inscribed on the doorframe of the reporting office indicated the tight-knit community of staff occupying the Glebe morgue.

Changes and challenges

During its twilight years at Glebe, the Coroner’s Court faced an array of unlikely challenges, dealing with everything from lawsuits and cultural issues to ferocious weather.

Despite the large refrigeration section of the morgue, which could hold just over 200 bodies, the facility still experienced occasional overcrowding. Several bodies were transferred from Glebe to neighbouring and interstate morgues due to congestion in 2009.[37] This was caused by the closure of Westmead Hospital’s morgue the previous year, which left the Glebe morgue as the only place in Sydney where forensic pathologists could conduct autopsies.[38] In 2014, a wild storm caused minor water damage and power losses to the facility, including the morgue area which was without refrigeration for several hours.[39]

In 2007, the family of a Māori hit-and-run victim protested outside the court, demanding that his body be returned intact with no organs retained by the morgue for future testing.[40] The burial of a whole body is a sacred aspect of Māori culture. Eighty members of the man’s friends and family performed a haka on the pavement outside the Coroner’s Court entrance. The protest showed the growing diversity of the community served by the court and the need for cultural sensitivity around a range of religious and cultural burial practices. There have also been respectful changes to the language used in the Forensic Medicine service. For example, ‘mortuary’ is now preferred to ‘morgue’ and ‘deceased person’ rather than ‘body’, ‘the dead’, ‘the deceased’ or ‘remains’. These changes have been made out of care and respect for bereaved relatives and friends.

In 2016, it was announced that the Coroner’s Court and the NSW Health Pathology Forensic Medicine service would be moved to a new multimillion-dollar complex in Lidcombe, which would incorporate the latest technology to streamline the court’s day-to-day functions.[41]

[media]The Lidcombe complex includes four state-of-the-art courtrooms to facilitate a more efficient inquest process. The new complex also focuses on creating a calming atmosphere for families and witnesses, with courtyard gardens and private viewing and rooms available for staff including Forensic Medicine Social Workers to meet and support bereaved families and others. This support may include the identification and viewing of deceased relative. The new complex opened in 2018, with the NSW Heath Secretary praising the ‘seamless collaboration between forensic medicine, coronial staff and police’.[42] The NSW Health Pathology Forensic Medicine service serves all of NSW with dedicated facilities in Lidcombe, Newcastle and Wollongong.

Transforming the old Parramatta Road site from investigating deaths to saving lives, the former Glebe Coroner’s Court was demolished in 2021 to make way for a new Central Sydney Ambulance Station.[43]

Notes

[1] Gideon Haigh, ‘Let the archives inspire your writing’. Melbourne Writer’s Festival, 2020. Accessed 22 September 2020 at: https://prov.vic.gov.au/about-us/our-blog/let-archives-inspire-your-writing

[2] New South Wales, Coroner’s Act 2009

[3] Coroners Court NSW, 2020. ‘History and values’. Accessed 18 September 2020 at: https://www.coroners.nsw.gov.au/coroners-court/history-and-values/history.html

[4] George III to Arthur Phillip, 2 April 1787, Historical Records of Australia, series 1, volume 1 (Melbourne: Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1914), p.4

[5] Hilary Golder, High and Responsible Office: a History of the NSW Magistracy (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 1991), p.117

[6] Hilary Golder, High and Responsible Office: a History of the NSW Magistracy (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 1991), p.117

[7] ‘Government and general orders’, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 20 October 1821, p.1.

[8] Colonial Secretary Index, State Archives and Records NSW, Reel 6021, 4/1094, p.55.

[9] Veronica Peek. ‘Charles Eaton, wake for the melancholy shipwreck’, 2019. Accessed 19 September 2020 at: https://veronicapeek.com/category/waterloo-creek-massacre

[10] New South Wales, An Act to Provide for the Attendance of Medical Witnesses at Coroners Inquests and Inquiries Held by Justices of the Peace 1838.

[11] Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority ‘Coroner’s Court (former) – shops and offices’, Heritage and Conservation Register, 2016. Accessed 23 September 2020 at: http://www.shfa.nsw.gov.au/sydney-About_us-Heritage_role-Heritage_and_Conservation_Register.htm&objectid=94

[12] Catie Gilchrist, ‘A tale of two morgues: Sydney’s deadhouses’, History no. 141 (2019), pp. 4–5.

[13] ‘Old Sydney’, Truth, 26 January 1908, p.9.

[14] ‘A doomed morgue’, Evening News, 17 June 1901, p.7.

[15] Catie Gilchrist, ‘A tale of two morgues: Sydney’s deadhouses’, History no. 141 (2019), pp. 4–5.

[16] New South Wales, An Act to Empower Coroners to Hold Inquests Concerning Fires 1861.

[17] Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority ‘Coroner’s Court (former) – shops and offices’, Heritage and Conservation Register, 2016. Accessed 23 September 2020 at: http://www.shfa.nsw.gov.au/sydney-About_us-Heritage_role-Heritage_and_Conservation_Register.htm&objectid=94

[18] New South Wales, An Act to Consolidate the Enactments Relating to Coroners’ Inquests, and to Magisterial Inquiries into the Cause of Death 1898.

[19] New South Wales, An Act to Give Coroners and Deputy Coroners the Powers and Duties of Justices; to Give Certain Magistrates the Powers and Duties of Coroners; and to Amend the Law Relating to Coronial Inquisitions 1901.

[20] Catie Gilchrist, ‘A tale of two morgues: Sydney’s deadhouses’, History no. 141 (2019), pp. 4–5

[21] New South Wales, An Act to Consolidate the Enactments Relating to Coroners’ Inquests, and to Magisterial Inquiries into the Cause of Death 1912.

[22] ‘Personagraphs’, Truth, 3 May 1925, p.8.

[23] Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority ‘Coroner’s Court (former) – shops and offices’, Heritage and Conservation Register, 2016. Accessed 23 September 2020 at: http://www.shfa.nsw.gov.au/sydney-About_us-Heritage_role-Heritage_and_Conservation_Register.htm&objectid=94

[24] New South Wales, Annual Report of the Director-General of Public Health (Sydney: Department of Health, 1961), p.25; C.J. Cummins, A History of Medical Administration in NSW 1788–1973, 2nd ed. (Sydney: NSW Department of Health, 2003), pp.96, 170.

[25] New South Wales, Annual Report of the Director General of Public Health for 1971 (Sydney: Department of Health, 1971), pp.230–1.

[26] ‘Another strike’, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 June 1914, p.9.

[27] ‘Court reports: smell in court holds up hearings’, Canberra Times, 26 July 1973, p.8.

[28] Carl Milovanovich, ‘The role of the Coroner and the Coroner’s Court’, paper presented at the State Legal Studies Teacher’s Conference, 30 March 2006.

[29] Jonathan Nichol, A Guide to Coronial Services in NSW for Families and Friends of Missing People (Parramatta: Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, NSW Department of Justice, 2015).

[30] Jonathan Nichol, A Guide to Coronial Services in NSW for Families and Friends of Missing People (Parramatta: Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, NSW Department of Justice, 2015), pp.4–5.

[31] Carl Milovanovich, ‘The role of the Coroner and the Coroner’s Court’, paper presented at the State Legal Studies Teacher’s Conference, 30 March 2006.

[32] Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority ‘Coroner’s Court (former) – shops and offices’, Heritage and Conservation Register, 2016. Accessed 23 September 2020 at: http://www.shfa.nsw.gov.au/sydney-About_us-Heritage_role-Heritage_and_Conservation_Register.htm&objectid=94

[33] Jonathan Nichol, A Guide to Coronial Services in NSW for Families and Friends of Missing People (Parramatta: Families and Friends of Missing Persons Unit, NSW Department of Justice, 2015), p.18.

[34] Coroners Court NSW, ‘Post mortem’, 2020. Accessed 18 September 2020 at: https://www.coroners.nsw.gov.au/coroners-court/the-coronial-process/post-mortem.html

[35] Coroner’s Court NSW, ‘Return of the body and organs’, 2020. Accessed 18 September 2020 at: https://www.coroners.nsw.gov.au/coroners-court/the-coronial-process/post-mortem/return-of-the-body-and-organs.html

[36] Jamelle Wells. ‘Love, empathy and a 24-hour operation – what life is like inside Australia’s biggest morgue’, ABC News, 27 May 2019. Accessed 18 September 2020 at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-05-27/australias-biggest-and-newest-morgue-in-sydneys-west/11142810.

[40] ‘Fury as morgue keeps brain’, Daily Telegraph, 19 September 2007. Accessed 17 September 2020 at: https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/fury-as-morgue-keeps-brain/news-story/7935eea242bfccc5e5301bff9ea540d6?sv=e72fc5db4e056d6ec72f8ec16fa824e3

[37] ‘Glebe full, so corpses sent to closed morgue’, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 October 2009. Accessed 17 September 2020 at: https://www.smh.com.au/national/glebe-full-so-corpses-sent-to-closed-morgue-20091008-gozf.html

[38] ‘NSW Opp calls on Govt to keep morgue open’, ABC News, 10 October 2008. Accessed 17 September 2020 at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2008-10-10/nsw-opp-calls-on-govt-to-keep-morgue-open/537108.

[39] Emma Partridge, ‘Flooding and power outage shut down Glebe morgue’, Sydney Morning Herald, 15 October 2014. Accessed 17 September 2020 at: https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/flooding-and-power-outage-shut-down-glebe-morgue-20141015-116dm8.html.

[41] Janet Fife-Yeomans, ‘Death of the morgue: the Glebe coroner’s complex goes west to Lidcombe’, Daily Telegraph. 27 January 2016. Accessed 17 September 2020 at: https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/death-of-the-morgue-the-glebe-coroners-complex-goes-west-to-lidcombe/news-story/cbc37709bf8d5ac277b48e736bb90817.

[42] Grace Ormsby. ‘Australia’s “largest” coroner’s court complex opens in Lidcombe’, Lawyer’s Weekly, 17 December 2018. Accessed 17 September 2020 at: https://www.lawyersweekly.com.au/wig-chamber/24680-australia-s-largest-coroners-court-complex-opens-in-lidcombe

[43] ‘New ambulance superstation for Sydney’, Health Infrastructure, 4 September 2020. Accessed 28 September 2020 at: https://www.hinfra.health.nsw.gov.au/newsroom/latest-news/latest-news/new-ambulance-superstation-for-sydney.