The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Irish in Sydney from First Fleet to Federation

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Irish in Sydney from the First Fleet to Federation

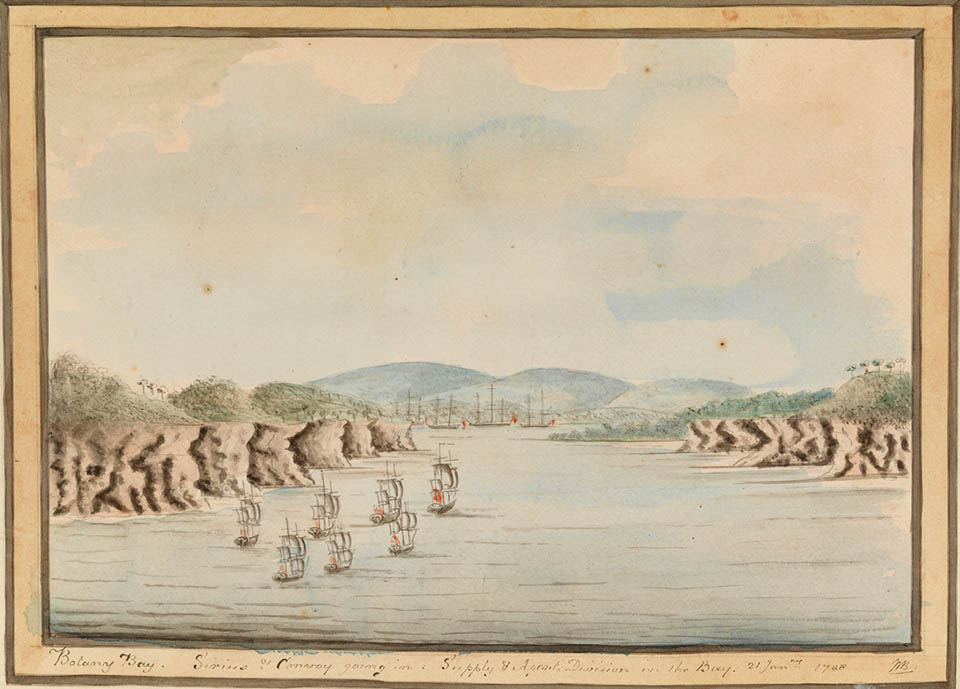

[media]Who was the first Irish person to see Botany Bay? Almost certainly either Joshua Childs of Dublin or Timothy Rearden of Cork, both sailors on Lieutenant James Cook's bark HMS Endeavour which sailed into the bay on 29 April 1770. [1] The first Irish residents of the new British convict settlement of New South Wales at Sydney Cove, however, arrived there on the supply ships and convict transports of the First Fleet on 26 January 1788. It is estimated that perhaps 10 per cent of those first European settlers of Australia had some Irish connection and among them was Hannah Mullens and her infant daughter. Hannah, who had had her sentence of death at the Old Bailey in London in April 1786 commuted to transportation for life, was, on her own admission, from Ireland. [2]

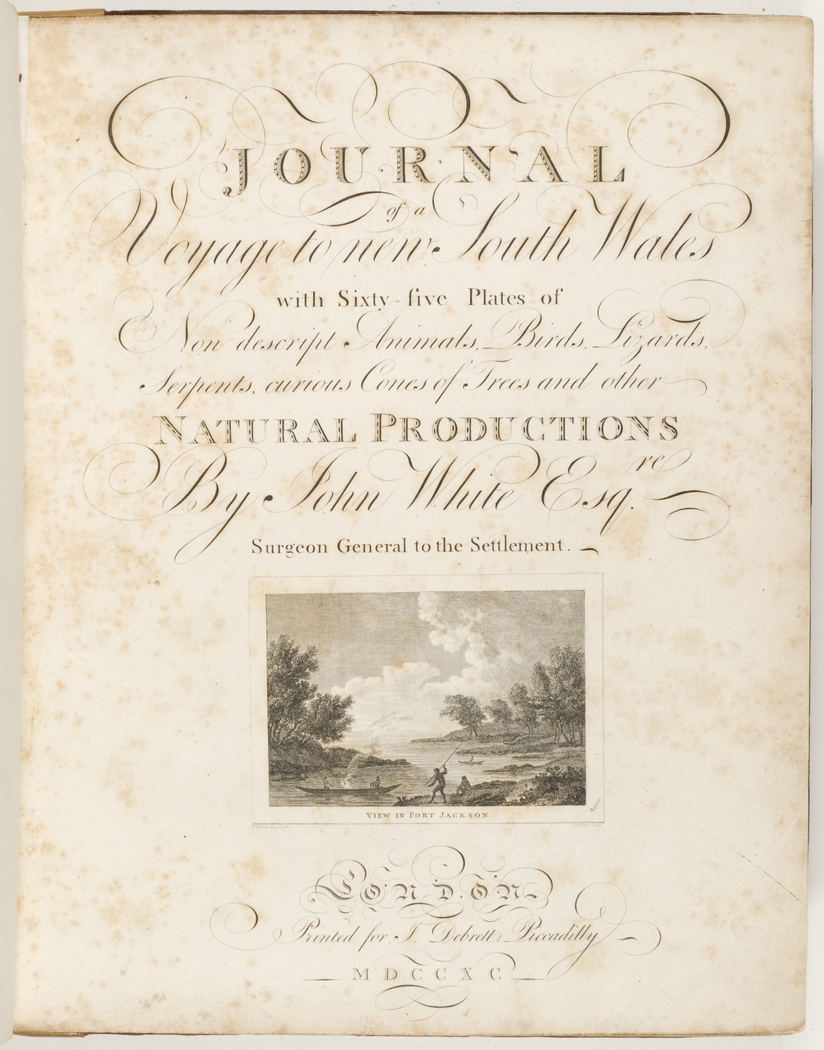

[media]Perhaps the most useful Irishman among those first Sydneysiders was Surgeon-General John White. White's medical skills came to the fore with the arrival of hundreds of seriously ill and dying convicts on the Second (1790) and Third Fleets (1791). With his assistants, and lacking medical supplies, White nursed many of them back to health. He also established good relations with the Aboriginal people of Sydney, famously singing to them on a couple of occasions and also allowing their sick to be treated equally in his tent hospital. White's major contribution to early Sydney was his Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, published in London in 1790, which covered not only the experiences of the convicts and settlers but also what were then seen as the exotic flora and fauna of this most distant of British colonies. Sixty-five colour plates adorned the Journal which went into many editions and was translated into French, German and Swedish. White was the first Irishman to provide such an in-depth account of the Sydney area. [3]

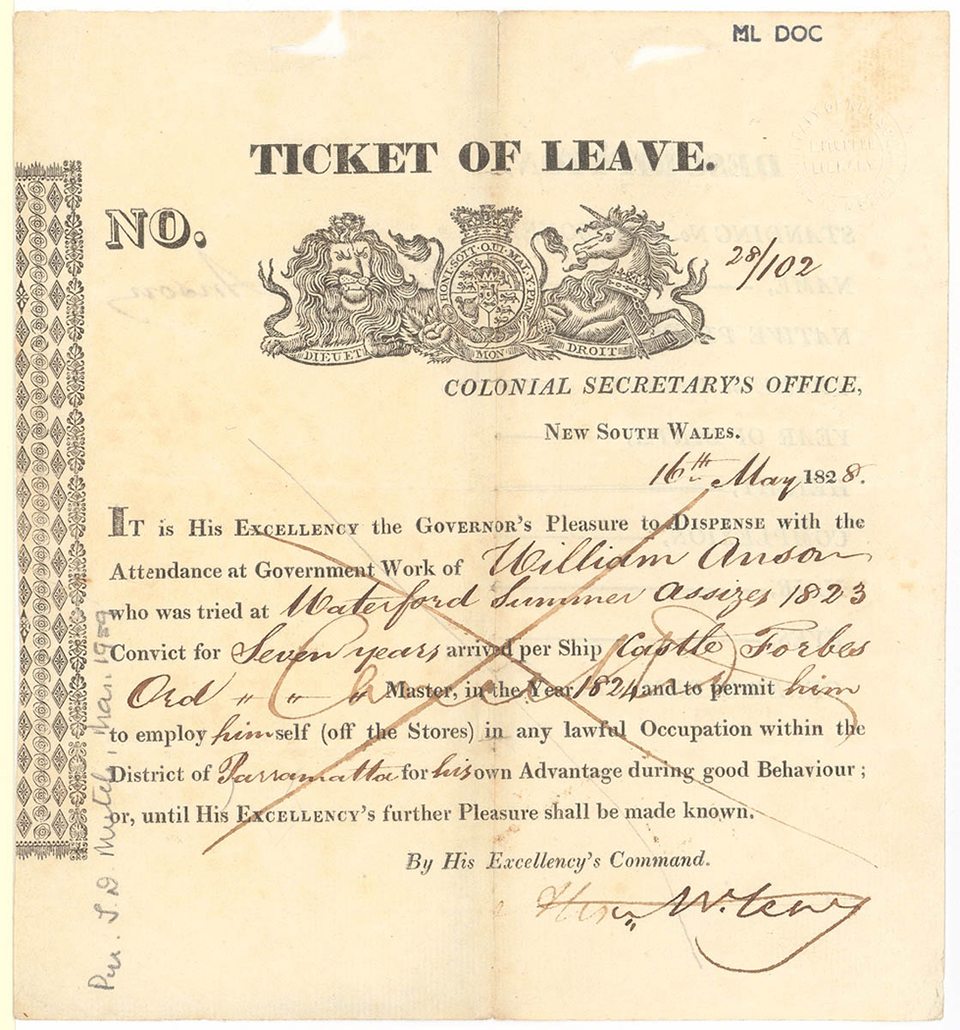

[media]Since the arrival of the First Fleet, and more particularly with the arrival of the first convict ship to sail direct from Ireland, the Queen in 1791, Sydney has received a constant stream of Irish immigrants and settlers. Until the late 1830s these were primarily, but by no means exclusively, men and women from every county in Ireland transported to the colony for crimes ranging from rebellion and high treason to petty theft. Of the 30,231 Irish convicts who came to New South Wales between 1788 and1840, whose first encounter with Australia was Sydney Harbour, 24,710 were men and 5,521 women. Many were assigned as servants into the interior of the colony, but perhaps 50 per cent remained in the expanding settlement of Sydney Town and its immediate hinterland. Here they, and their colonial-born children, formed the bulk of Sydney's Irish- born and Irish-derived population and the great majority of these were Catholic in religion. [4]

It is impossible to generalise about the fate of these early Sydney Irish. Mary McCarroll, a 'flower keeper' aged 33, was transported from Dublin in 1814. Assigned as a servant to an English ex-convict publican in the Rocks, Stafford Lett, Mary soon married English convict George Marshall who became a successful clothier and blanket maker at the Brickfields. George Marshall died in 1828 as his business affairs were prospering and over the 10 years that followed his Irish ex-convict widow raised their two children and built on the money and property he left her. At her death in 1838, Mary Marshall was described in the press as 'one of the oldest settlers in the colony, and who was greatly esteemed for her industrious and amiable disposition'. No mention was made of her convict past. Mary Marshall's time in Sydney was in stark contrast to that of Mary Grady, transported from County Kerry, aged 18, in 1806. In 1808, Grady broke into a house stealing 'cash and notes', for which crime she was sentenced to death and hanged in public.

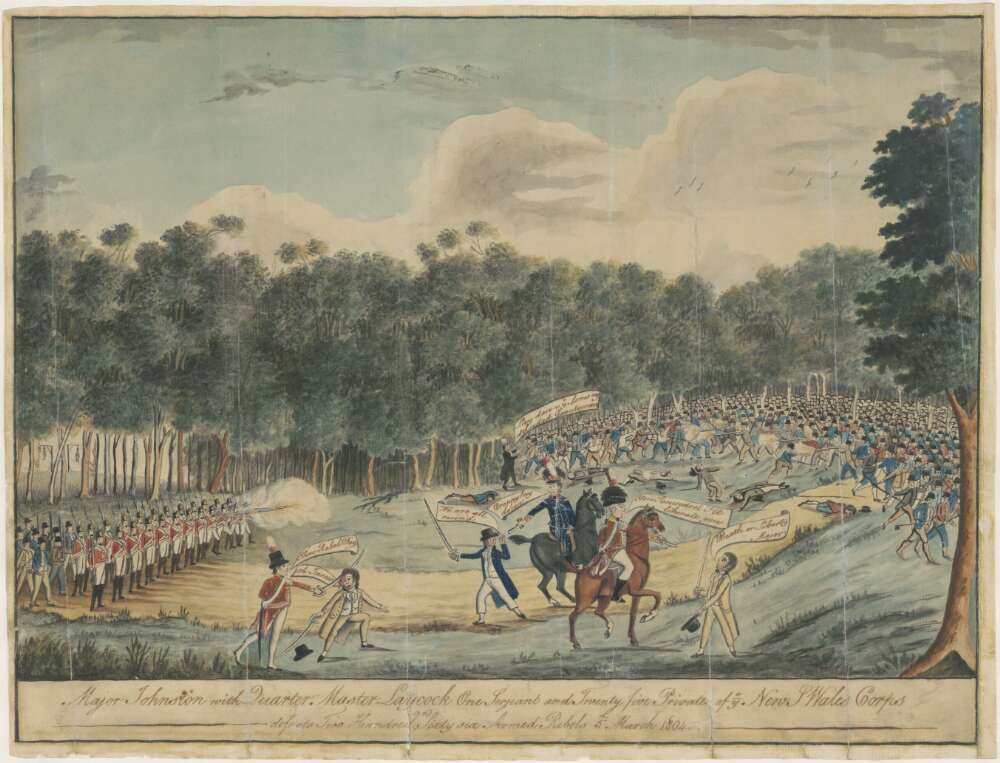

Ireland's [media]most famous contribution to Sydney's early history was the convict rebellion at Castle Hill in 1804. Irish patriots, who had been transported for their part in the 'Great Rebellion' of 1798 in Ireland, took up arms again with the intention of stealing a ship in Sydney Harbour and fleeing the colony. Nine rebels were hanged, some received brutal floggings and others were sent to the mines at Coal River (Newcastle). A memorial at Castlebrook Cemetery near Rouse Hill marks the reputed site of Sydney's only rebellion against the Crown. [5]

How did Irish convicts get on in this penal settlement? The 1828 census showed there were 11,236 Catholics in the colony, the great majority of them Irish or born of Irish parents, and of these 25 per cent lived in Sydney Town and district. One historian who has carefully studied their situation concluded that despite their arrival as felons or rebels, and their impoverished Irish backgrounds, many had done well and that in terms of wealth and occupation they covered a 'wide spectrum of society'. [6]

Governor Sir Richard Bourke

[media]The 1830s brought great changes for the Sydney Irish and for the colony of New South Wales. In 1832 Australia's first Irish governor, Sir Richard Bourke, took over the colonial administration. During his five years in office Bourke left a legacy which affected all forms of Sydney life; his Church Act ensured equal treatment of religious denominations eager for government assistance; he tried to bring in the Irish National School system which would have had all colonial children educated in the same government schools; and he introduced reforms which curbed the powers of local magistrates over convicts. Bourke's attempts at educational reform grounded on the rocks of religious intolerance, for while the Catholics supported him, the majority of the Protestant clergy would not have a bar of this Irish-style system. Nevertheless, it became the basic model eventually adopted by all the eastern Australian colonies for 'free, public and secular' education over the next decades.

Perhaps Bourke's most significant influence was on the gradual shift in the nature of immigration, from convicts to free 'government assisted' immigrants whose passages were largely paid for out of colonial funds. Soon the balance between convict and free swung decisively in favour of the free and in 1840, three years after Bourke's departure, the British government ended transportation to New South Wales. This free immigration was also heavily Irish and in 1841 more than 13,700 Irish came to New South Wales, fully 68 per cent of that year's total influx from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. By 1846, the Irish-born formed 27 per cent of the population of the central city of Sydney, and Catholics 31 per cent. The Catholic proportion would have been even higher had not some 17 per cent of the free Irish immigrant intake been Protestant.

[media]When Sir Richard Bourke left Sydney in 1837 to retire to Ireland, large crowds ran along the shores of the harbour cheering the popular governor. In 1842 Sydney's, indeed Australia's, only statue of a British colonial governor built with money raised by public subscription was unveiled in the Domain overlooking the Botanical Gardens. The Irish Catholic Judge Roger Therry told a huge crowd gathered for the occasion that Bourke had come to New South Wales,

to light up the lamp of knowledge in the cottage of every peasant, and on the stall of every mechanic, and proclaimed to every emigrant who touched these shore that freedom to worship God according to conscience. [7]

Churches, convents and schools

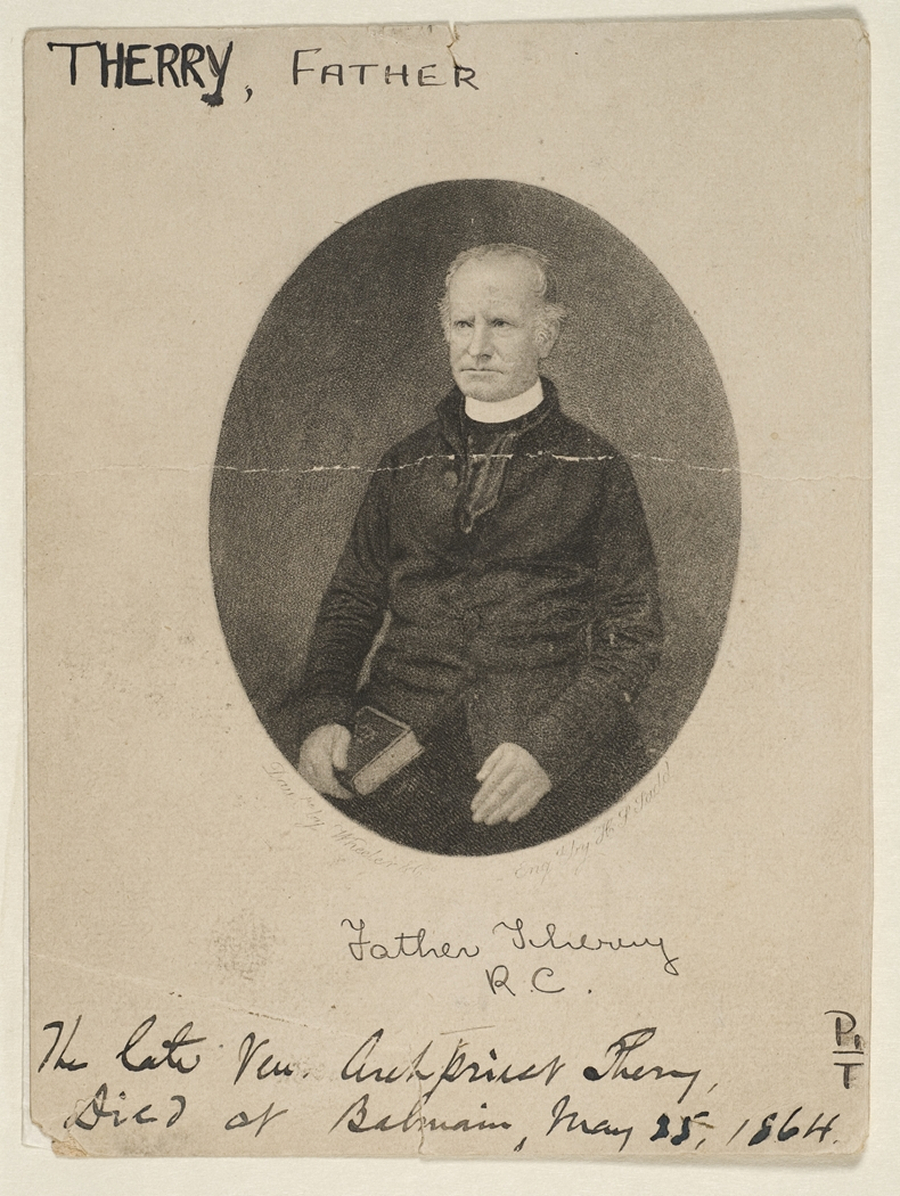

'Freedom to worship' was [media]soon taken up by the Irish in nineteenth-century Sydney. Indeed, to other settlers, the most visible sign of the Irish presence in the expanding city and its suburbs were the Catholic buildings. The foundation stone of the colony's first Catholic church, St Mary's Chapel (later Cathedral), just beyond the convict barracks at Hyde Park, was laid by Governor Lachlan Macquarie on 29 October 1821. In the presence of Irishman Father Joseph Therry, one of Sydney's first [media]two official Catholic government chaplains, the governor in a short speech made it clear that that there was more to official support for the building than the desire to foster religion:

I have every hope that the consideration of the British Government, in supplying the Roman Catholics of this colony with established Clergymen will be the means of strengthening and augmenting (if that be possible) the attachment of the Catholics of New South Wales to the British Government, and will prove an inducement to them to continue ... loyal and faithful Subjects to the Crown. [8]

The [media]second church to be built made more of a national statement. On 25 August 1840 William Davis, transported as an Irish rebel in 1800, stepped forward at a large Irish and Catholic gathering in the Rocks and placed a cheque for £1,000, an enormous sum, on the foundation stone of St Patrick's Church. Davis also gave the site for the church. St Patrick's was opened on 18 March 1844, the day after St Patrick's Day to prevent the possibility that such a gathering on the saint's national day would be marred by inebriated revellers. The ceremony was preceded by a large parade, from St Mary's, down King and George streets, and up Charlotte Place, featuring the St Patrick's Band, the St Patrick's Total Abstinence Society and the members of the St Patrick's Building Society. The banners of the societies were carried in front of the parade and it would have been clear to all that Irish and Catholic Sydney was on show. It was, so it is said, the largest public parade of its kind yet seen in Sydney. The city's Catholic paper, the Morning Chronicle reported the occasion; The Sydney Morning Herald ignored it. [9]

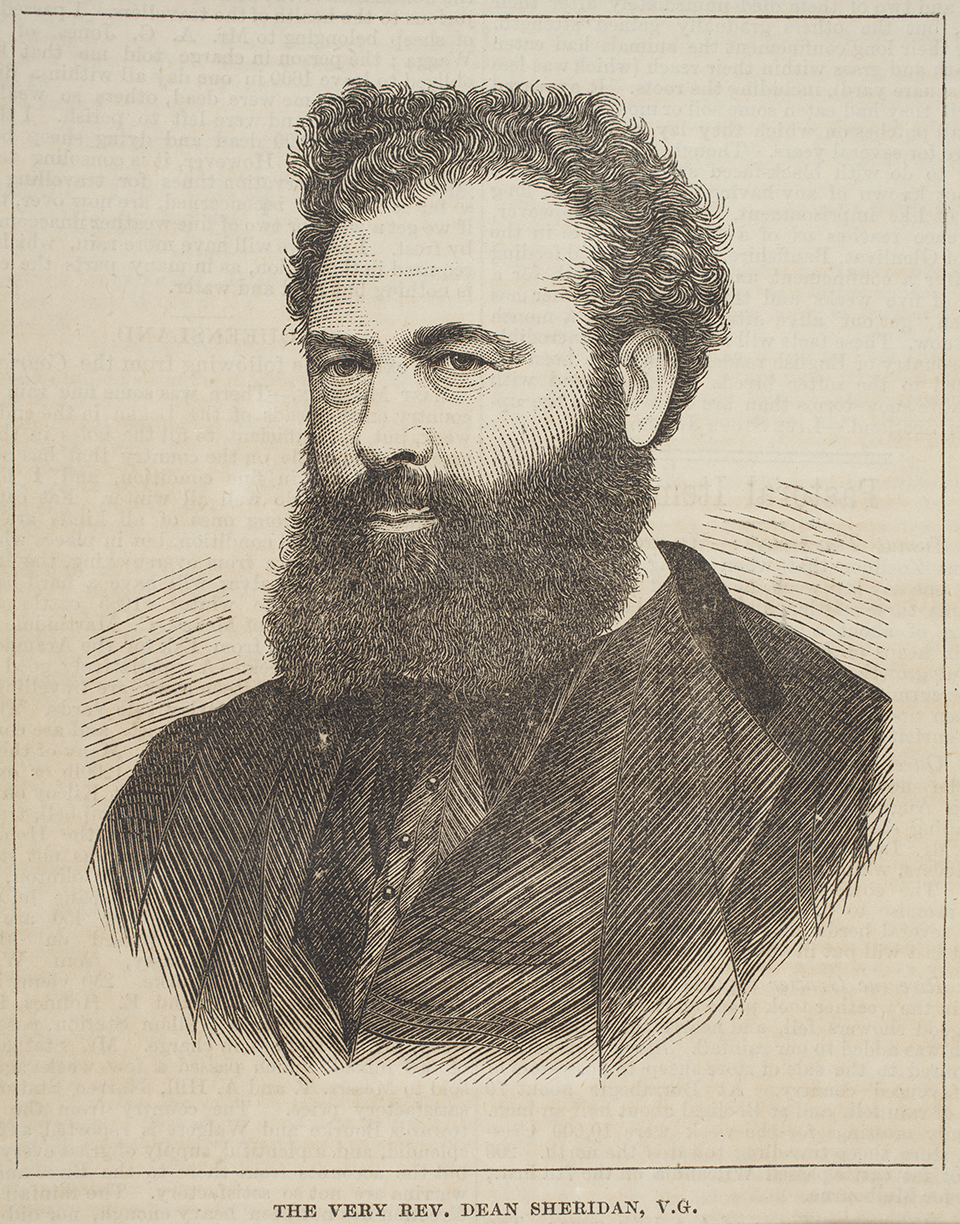

[media]As Sydney's population expanded throughout the century so did the establishment of Catholic churches in the city and suburbs. These became centres of Irish and Catholic community life. St Francis de Sales church in the Haymarket parish was opened in 1864 and its first resident priest was Irishman Father John Felix Sheridan, who ran this new parish for 21 years from 1867. Sheridan was renowned for his performances at school concerts:

... he'd go on to the stage ... and he'd take his fiddle out of the case and bendin' over it near the piano he'd bring out of it the quarest squawks you ever did hear ... Then he'd rub the rosin on the bow, and he'd give 'em the 'Irish Washerwomen', and every toe in the hall went tap, tap, tappin' to the swing of it; then when he'd come to the last lap, with a twinkle in the eye, he'd step up the pace, and faster and faster still he'd go, till there wasn't a boot could keep up with him. [10]

Sheridan's work as a parish priest mirrored much of the organisational growth of Irish and Catholic Sydney; he ran bazaars to raise money to extend the church, and to build a temperance hall, a school and a convent.

Irish [media]religious orders also had a major impact on the provision of Catholic educational and social welfare facilities. On 31 December 1838, five nuns of the Irish Sisters of Charity arrived in Sydney to care for the sick and poor and walked everywhere in their distinctive habits, ministering to needs in hospitals, orphanages, gaols and schools. Two of this order's most conspicuous legacies to the Sydney landscape are St Vincent's Hospital, which they founded for the poor in 1857, and their secondary school for girls, St Vincent's College in Potts Point, where the first principal was Tipperary woman, Sister Mary Ursula Bruton. Also [media]making a major contribution to Catholic education were the Irish Sisters of Mercy. In 1888 Cardinal Patrick Moran brought a group of Mercys to Parramatta where they ran and taught in St Patrick's Primary School and, in 1889, founded a secondary school for girls, Our Lady of Mercy College. Sisters from both orders, and other Irish women religious, became the backbone of the teaching staff in Catholic primary schools throughout the city and suburbs.

[media]Irish religious orders were also prominent in the education of Catholic boys. The Irish Christian Brothers came to Sydney in 1843 and taught in Catholic schools in the Rocks, in Macquarie Street and on Broadway but left after disagreements with the existing church hierarchy. They returned in 1887 and opened a school in Thames Street, Balmain. Catering to boys whose parents were climbing the heights of the colony's social tree was St Ignatius College, Riverview, [media]founded by Irish Jesuit Father Joseph Dalton in 1880. Early pupils included Thomas Joseph Dalton, offspring of the wealthy Dalton family of Orange, New South Wales, whose origins lay in famine-ridden County Limerick, and the famous [media]poet Christopher Brennan, whose parents were born in Ireland. Neither family harboured much love of British rule in Ireland. [11]

The provision of Catholic education fell squarely on the shoulders of the Catholic community. The New South Wales Public Instruction Act of 1880, introduced by that avowed enemy of Irish Catholic immigration Sir Henry Parkes, removed public financial support for any denominational schools. [12] Seeing the state schools as places of 'Godless instruction', the Catholic Church set out to provide a Catholic education for all the city's Catholics and to do this it relied on the financial support of Catholic parents. It took some time for enough Catholic schools to be built to accommodate all Catholic children, many of whom continued to attend state schools well into the twentieth century.

A practical Catholic organisation, the New South Wales branch of which was founded in Sydney in 1880, was the Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society. The Hibernians based themselves on the Catholic parishes and had a triple role; to provide sickness, hospital and funeral benefits for members through subscriptions, to cherish the memory of Ireland, and to foster loyalty to Australia, their adopted home. Hibernians, in their colourful green and gold regalia were prominent in the organisation of St Patrick's Day activities and in many other social occasions run by branches. [13] On 26 December 1890, 2,000 Hibernians were conveyed by ferry to Chowder Bay for their annual picnic. At another picnic on 6 October, also at Chowder Bay, picnicking Hibernians had come to the aid of policemen being pelted with stones and other missiles by members of the 'Gipps Street' larrikin push. [14] Between 1891 and 1905 there was a Hibernian Band which functioned largely with the help of 'good natured Germans ... in green jackets and a hat with a green cockade'. [15]

Nice girls from Tipperary

[media]The growth of Sydney's Irish and Catholic population after the 1840s was closely tied to the continuation, until the mid-1880s, of government-assisted immigration from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Between 1848 and 1870, more than 44,000 Irish arrived in Sydney as assisted immigrants and perhaps 50 per cent of these stayed in the city and adjacent districts. While the accents of every county and region in Ireland were to be heard in city streets, prominent among them were the sounds of Clare and Tipperary, the home counties of nearly one third of all the immigrants. The story is told of Caroline Chisholm that, when taking a group of Irish girls into the country in the1840s to find them employment, she was accosted by a bushman farmer asking for wife, a 'nice girl from Tipperary'. She promised to find him his heart's desire. [16]

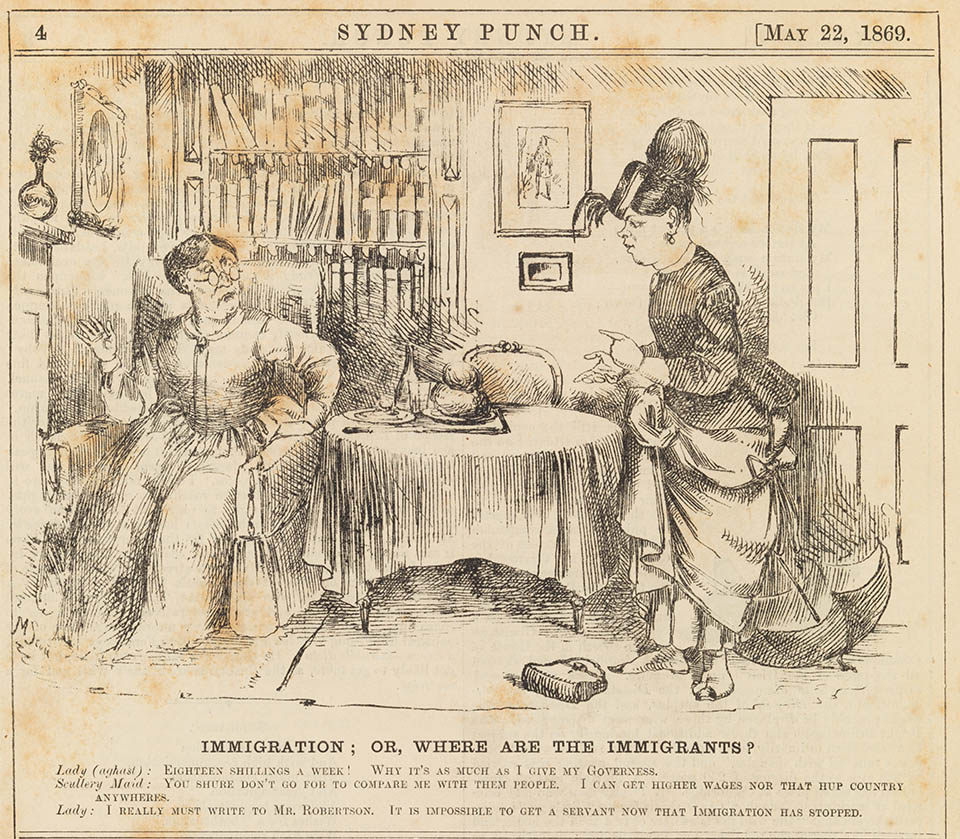

[media]Many of the nice girls from Tipperary, however, were not attracted by bush life. Mrs Marion Pawsey, who from 1846 ran a Sydney employment agency looking for suitable female domestic servants for the city's middle classes, told the NSW Select Committee on the Working Classes in 1860 that she could get no takers for what are now considered city suburbs:

In speaking of the country, is it within your knowledge that many girls consider 3 or 4 miles out of town as the country?

They do; they consider Waverley, Balmain, the North Shore as the country.

They draw a distinction between those places and the centre of the city.

They do. [17]

[media]Another employment agent, William Haigh, found the Irish reluctant to leave the city as they were 'fond of dress, of change, of city life'. [18] This reluctance can be tested against the hiring agreements for 29 single Irish women between the ages of 16 and 26 who arrived in 1864 on the Ocean Empress and were hired from the New South Wales Government Female Immigration Depot at Hyde Park Barracks. Only three of them could be said to have taken employment in the 'bush' – one at Cooks River, another at Jamberoo and a third going to the Lachlan River district. Most of the rest became general servants in households in Castlereagh, Pitt, Bligh, Parramatta, Fort and Crown streets or in locations like the Glebe, Watsons Bay or Hunters Hill. [19]

[media]During the 1850s and 1860s, a common sight in the streets leading from Circular Quay to the Hyde Park Barracks was a column of recently arrived single immigrant women walking behind drays carrying all they brought with them to the colony in large sea chests. Through the old convict barracks, transformed in 1848 into the offices of the New South Wales Immigration Department and a reception centre and clearing house for single assisted immigrant women, passed thousands of Irish women either waiting to be picked up by family or friends who had sponsored their passage, or seeking their first colonial employment. Of 1,781 women who passed through Hyde Park between January and June 1855, 1,258, or 71 per cent, were from Ireland. [20]

Irish female dominance in the labour market for domestic servants was the cause of much complaint in Sydney. The question of Irish women's suitability for making beds, sweeping floors and dealing with other household chores surfaced in the official report of the Government Immigration Agent, Englishman Captain Henry Browne, in 1854. He wrote of the single female immigrants:

The single females were, I regret to say, the most inferior since the Orphan Immigration that have come under my observation. They were, for the most part, unaccustomed to any of the occupations of domestic servants. [21]

[media]There was little doubt in anyone's mind that Browne meant 'Irish' when he used the word 'inferior' and the orphans to whom he referred were the more than 2,200 young girls from Irish workhouses sent out to the colony under the Irish orphan emigration scheme at the height of the 'Great Famine' between 1848 and 1850. Being young and inexperienced, their employment was organised by an Orphan Immigration Committee and they were seen as in need of official supervision before being left to their own devices. It was to receive the first shiploads of Irish orphans in 1848 that the Hyde Park convict barracks had been turned into the Female Immigrant Depot. [22] Sydney's Irish community was so outraged at Browne's apparent slur on the capacities of Irish women servants that the Legislative Assembly set up a Select Committee in 1858 to look into his allegations. The committee reported that Browne had only the orphan girls in mind when making his comments – a highly dubious conclusion. [23]

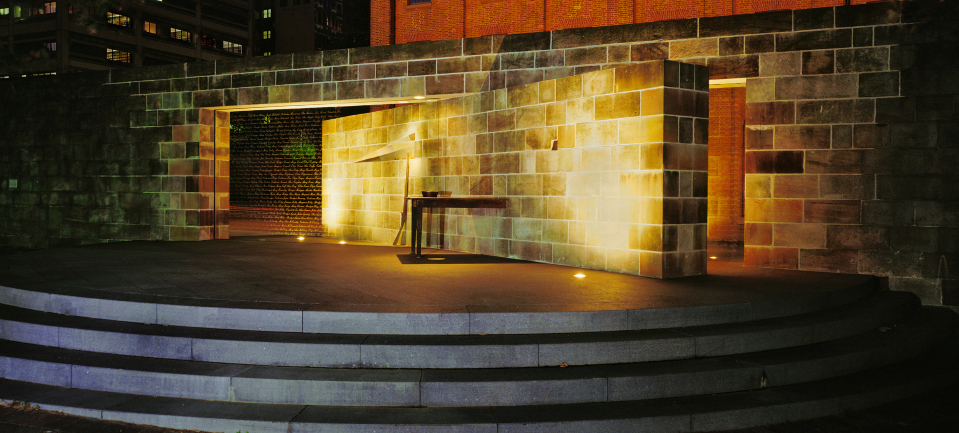

Interestingly, 150 years [media]after the arrival of the orphan girls, it was this group of young, vulnerable, famine dislocated immigrants that the modern Irish immigrant community in Sydney wished to remember and commemorate. In many ways this was a response to the state-sponsored commemoration in Ireland between 1995 and 1997 of the 'Great Famine' of 1845–1850, a process which produced the nation's first national memorial to that tragic event, at the foot of Croagh Patrick Mountain in County Mayo. During the 'Great Famine', more than a quarter of Ireland's population of eight and a half million died or emigrated. In 1999, Sydney's 'Irish Famine Monument' was dedicated, funded largely by subscriptions from the Irish community, with major donations from the Irish government, the Australian government and the state of New South Wales. This most imaginative structure was built into the southern wall that surrounds the building through which every Irish famine orphan who came to Sydney had passed during her first days of a new life in Australia – the Female Immigrant Depot. [24]

The shots at Clontarf

Immigration Agent Browne's attitude was only one example of a wider [media]hostility towards Irish Catholics among the majority English and Scottish Protestant population of the colony. Despite their origins in a political unit called the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, emigrants from those islands were far from united about many aspects of political and religious life. Throughout the nineteenth century, as Sydney's population grew, fed mainly by a continuing stream of English, Scottish and Irish immigrants, and their locally born children, the divisions of the old lands surfaced in the city. In particular, Irish Catholics' support for greater degrees of Irish political independence at home, and the desire of many of them for a religiously based education system for their children, seemed to set them apart from their more British-oriented neighbours.

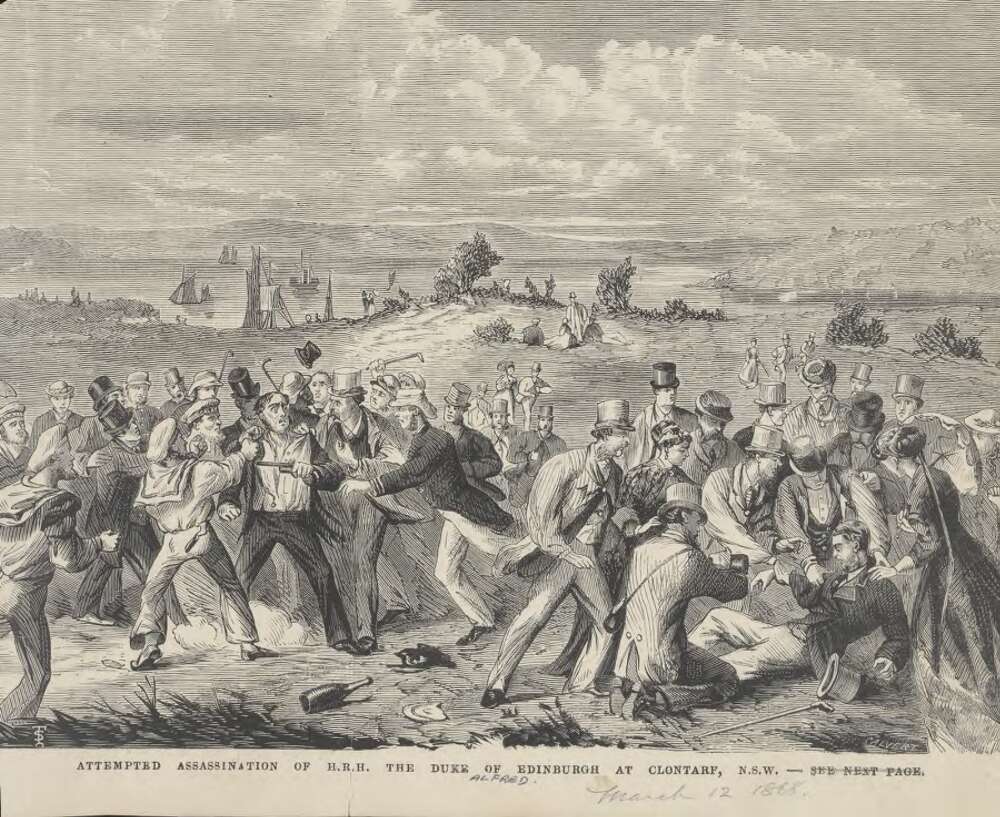

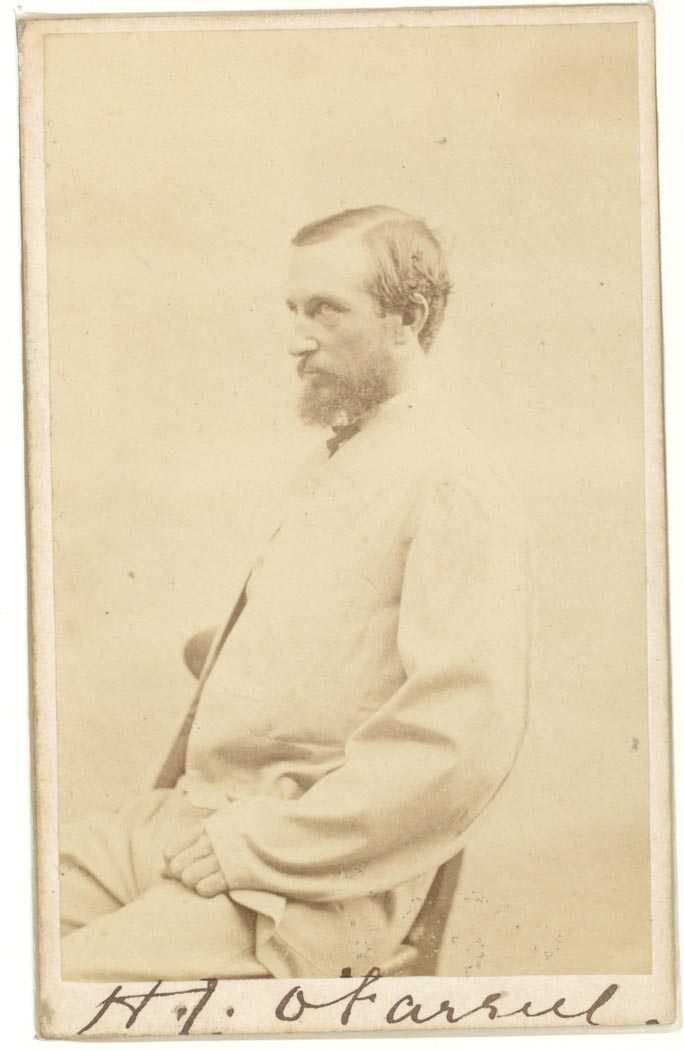

[media]On 12 March 1868, at a picnic park at Clontarf, the worst fears of those suspicious of Irish Catholics were realised. Irishman Henry James O'Farrell attempted to assassinate Australia's first royal visitor, Queen Victoria's fourth child and second son, Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh. He fired two shots at the Duke, one of which went into his back, but the second was diverted when a bystander struck the pistol from O'Farrell's hand. The would-be assassin was instantly arrested and transferred to Darlinghurst Gaol, while the Duke, who fortunately was not too seriously wounded, was rushed back to Government House where a makeshift hospital was devised in the main drawing room. His Royal Highness quickly recovered: O'Farrell, who claimed to be a member of a secret Irish republican movement, the Fenians, was just as quickly tried and hanged. The chief prosecutor at O'Farrell's trial was Irish Catholic-born Sir James Martin, after whom Martin Place is [media]named, a man who had long turned his back on his Irish and Catholic origins. A rather worn-looking plaque under a large palm tree near the park at the eastern end of Clontarf Beach marks the spot where O'Farrell fired the shots. Anti-Irish feeling became intense, both in the bush and in the city, as the Colonial Secretary Henry Parkes claimed there was an Irish Fenian plot to take over the colony. The longer term effects of the O'Farrell incident simply heightened feelings of division and otherness between Catholic and Protestant Sydneysiders. [25]

Loyalty to the British throne

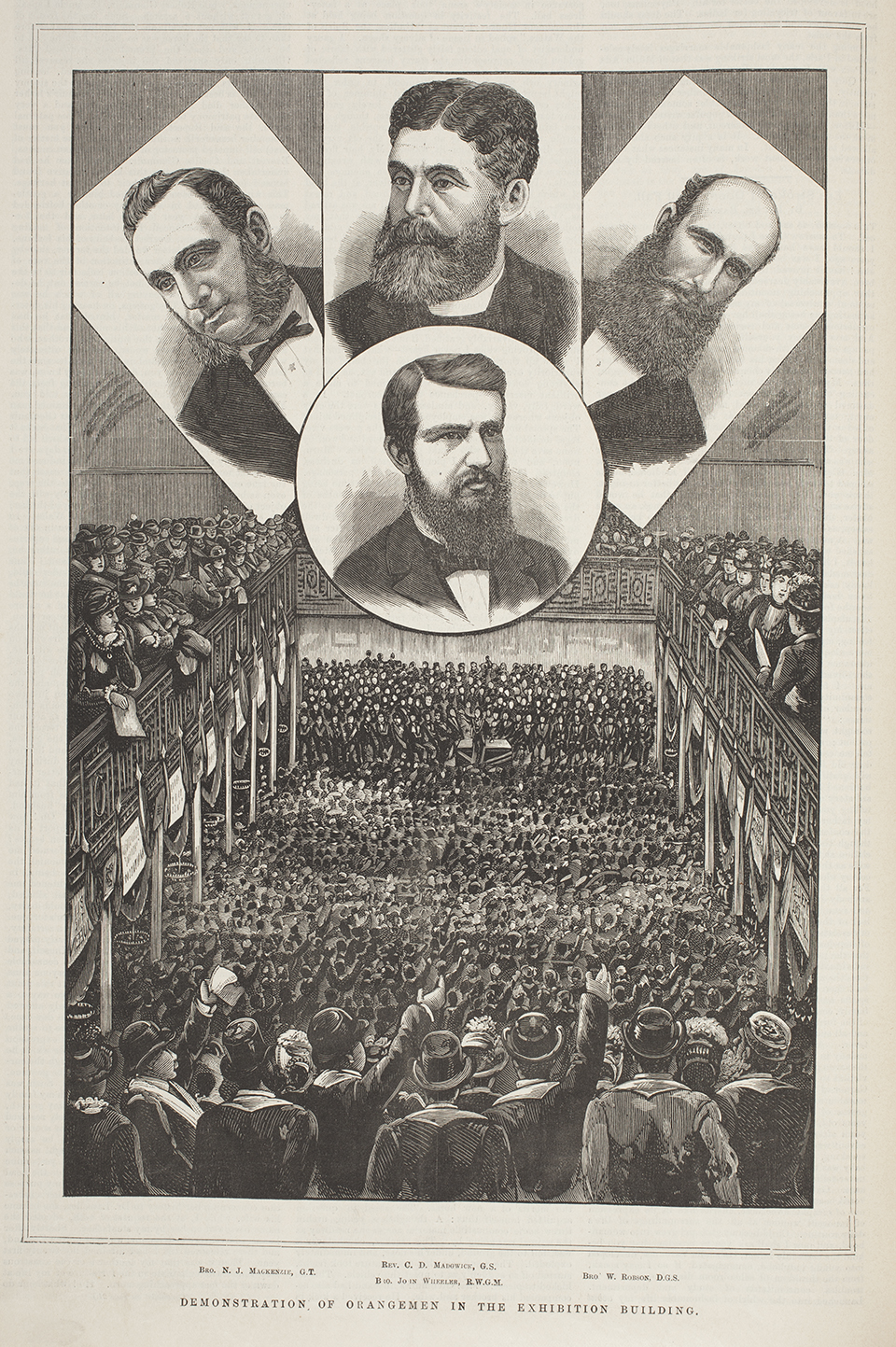

Symptomatic of this [media]growing rift between Protestant and Catholic after the attempted assassination of Prince Alfred, was a resolution from an organisation, Irish in origin but the very model of British Empire ultra-loyalism – the Grand Orange Lodge of New South Wales. On 23 March 1868, at a large meeting in the Lyceum Schoolroom in Bathurst Street, the assembled Orangemen passed a solemn resolution to the Earl of Belmore, the Irish Governor of New South Wales, which contained the following sentence:

... on behalf of the members of the Loyal Orange Institution [we] desire to approach Your Excellency, to express our sentiments of unswerving loyalty to the British throne, to Your Excellency, and to the Government by law established. [26]

At this same meeting a Mr B James spoke of disloyalty in high official circles, as evidenced by a judge who was present at a banquet in Goulburn to celebrate the inauguration of a Catholic bishop when a toast to 'the Pope's health was drunk before that of the Queen'.

The Orange Order, formed by Protestant farmers in Ireland in the late eighteenth century, was dedicated to uphold the link between Ireland and the British monarch as the defender of the Protestant faith. Catholics were, almost by definition, potentially disloyal and needed to be opposed. Between 1848 and 1870, just under 20 per cent of all the Irish assisted immigrants were Protestant in religion and the majority of them came from counties in the west of the northern province of Ulster, where the Orange Lodge was strong. By the 1840s there are references in the Sydney press to 'various Orange Lodges in the city' and certainly by the 1860s the organisation was well established. By the late 1860s the meetings of the city's Orange Lodges were being regularly advertised in the Sydney Morning Herald. [27]

[media]The great day in the year for the Orangemen was the so-called 'Glorious Twelfth', commemorating 12 July 1690, when King William of Orange defeated an Irish Catholic army at the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland and thereby, in the eyes of the Orangemen, kept Ireland safe for the Protestant religion. At one such celebration on 12 July 1886, in the Sydney Exhibition Building, between 8,000 and 12,000 Orangemen, all dressed in Orange regalia, listened to that great champion of British Protestantism, English-born Sir Henry Parkes (later famous as the so-called 'Father of Federation'), speak of their institution

which teaches a love of the liberty of conscience which is the root, and at the same time the fruit of our common Protestant faith. [28]

It was Parkes in 1869, in the New South Wales Parliament in Macquarie Street, who spoke in favour of restricting the numbers of Irish Catholics, citizens like him of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, from coming to New South Wales as government-assisted immigrants.

However, there were many positive contributions by Irish Protestants to the life of nineteenth-century Sydney. Harriette McCathie ran 'Mrs McCathie's Hat Shop' in King Street; Henry Clarke had a large produce agency, Clarke & Son, in Sussex Street; John Frazer built up one of the city's largest wholesale grocery businesses, John Frazer & Co, in York Street. Frazer presented the city with an unusual gift, two canopied drinking fountains, one of which, placed in St Mary's Road near the cathedral, was described as 'a beautiful invitation to passers-by to come and drink'. It stands there still, but sadly without water. [29]

The spread of the Sydney Irish

So [media]how Irish did Sydney become in the nineteenth century? As described above, in 1846 the Irish-born population of Sydney, as a proportion of the total population, reached its height. In that year, 27 per cent of the inner city population was Irish-born. By 1851 this had slipped to 22 per cent; it was 20 per cent in 1861; fell to 16 per cent in 1871; and was 13 per cent in 1901. The Catholic proportion of the city, however, rose to 33 per cent in 1861 and by 1901 every third person living in the central wards of the city was Catholic. The great bulk of this Catholic population was Irish-derived. This figure, however, probably slightly understates the Irish origins of some inner-city dwellers, as between 15 and 20 per cent of the Irish immigrant intake of nineteenth-century Sydney was Protestant in religion, and the colonial-born children of these immigrants would probably bring the Irish-derived population of inner Sydney by 1901 to at least 35 per cent. [30]

As Sydney grew and pushed out to new suburbs, the Irish followed. In 1861, in a cluster of locations close to the city such as Glebe, Redfern, Botany and Paddington, the Irish-born population was above the colonial average of 15.6 per cent. The Catholic population of these suburbs in 1861 hovered around the 20-25 per cent mark. In 1891, 20 per cent of people in Sydney's outer suburbs were Catholic, with 21 per cent in 1901. However, in 1901 the percentage of Catholics in a suburb could range from just 7 per cent in Hunter's Hill, to 27 per cent in Paddington.

Traditionally, this settlement pattern is seen as the relative crowding of the Irish and the Catholic working class into the inner suburbs and into the city of Sydney itself. These areas were regarded as slums at the time, and might suggest that Irish and Catholics were among the most disadvantaged groups in colonial Australia. The late Professor Oliver MacDonagh, while he saw the Irish as clustered at the bottom of the economic pyramid, always felt that they were but a step or two behind their English and Scottish co-workers in Australia, by comparison with other overseas destinations. [31] A recent analysis by Professor Malcolm Campbell, moreover, shows that by the census of 1901, the Irish-born, male and female, were broadly represented across all occupational groups in New South Wales, proportional to their numbers in the population. Campbell concludes, and it is a conclusion which merits much further study in relation to Sydney's nineteenth-century ethnic mix:

There is little evidence that Irish immigrants in general were locked into a narrow band of disadvantageous occupations or consigned disproportionately to the bottom rungs of the occupational ladder. [32]

Rebels or Queen's men?

[media]While the Irish may have been less disadvantaged than is generally supposed, in late colonial Sydney there was much that set them apart from majority colonial life and opinion. Irishness sometimes manifested itself in confronting ways such as the displays of Irish distinctiveness on St Patrick's Day, or Irish support in Sydney for movements in Ireland which seemed to threaten the unity of the colonial motherland, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The observance of St Patrick's Day went back to virtually the foundation of New South Wales with Governor Macquarie giving the celebration of the day official sanction; others complained that their convict workers marked the day by remaining in a drunken state for up to a week.

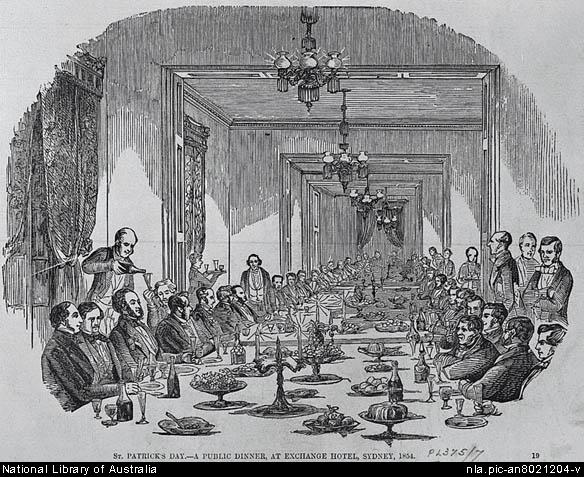

[media]Throughout the century the nature of the St Patrick's Day celebrations varied. The well-heeled attended banquets and dances while Catholic schoolchildren held processions through the streets to attend mass. In 1882, the day was marked with a mass at St Patrick's Church, a procession by the members of the Hibernians and the Australian Holy Catholic Guild accompanied by bands, and a large picnic at Chowder Bay. While newspapers like the Sydney Morning Herald were restrained and respectful in their coverage of these events, anti-Irish feeling was often in evidence, as in the Illustrated Sydney News's report on the 1883 St Patrick's Day celebrations at Botany. Their drawings of the day depicted cudgels in the hands of the male revellers, an obsequious attitude towards the priests in a drawing entitled 'His Riverince', general rowdiness, and in a drawing entitled 'The Wearing of the Green', a gathering being addressed by a rousing speaker who was more than likely ranting on about the grievances of old Ireland. [33]

The 1880s was a dramatic decade for the Sydney Irish. In the mother country, the 'Home Rule' movement, led by the Irish National Party at Westminster, was demanding the restitution of a separate parliament in Ireland for purely Irish affairs. When Irish National Party politicians William and John Redmond visited Sydney in 1883 to raise money for the cause, deep divisions emerged between supporters of Home Rule, largely Irish and Catholic, and other Sydneysiders who saw it as threatening the integrity of the British Empire. In late February, John Redmond was scheduled to address a meeting in the Masonic Hall when loyal English members of the order protested, and the Home Rulers were obliged to look for another venue.

On 6 March 1883 a stormy meeting was held in the Protestant Hall, Castlereagh Street, presided over by the Mayor of Sydney, Protestant Irishman John Harris. Sir Henry Parkes led the speeches against the Redmond mission by claiming that Australians should not import the divisions of the old country, but then gave the game away by claiming that the Redmonds and the Irish National Party were basically the promoters of violence and rebellion. [34] The state of Ireland was prominently reported in the Sydney papers with headlines full of words such as 'outrage', 'conspiracy', 'arrest' and 'insidious'. Then, in 1885, the British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone was converted to 'Home Rule', after a sweeping victory in Ireland for Home Rule candidates. For many of a more liberal political persuasion in Sydney, this made 'Home Rule' more acceptable and those who supported it less of a threat.

[media]Also at this time, in 1884, the Sydney Irish welcomed the first Irish Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Patrick Francis Moran. Nobody in the city would have missed his arrival. As the Liguria, the ship bearing the Archbishop, steamed up Sydney Harbour, it was met by 'twenty steamers decked with green bunting, banners and flowers, carrying instrumental bands'. [35]

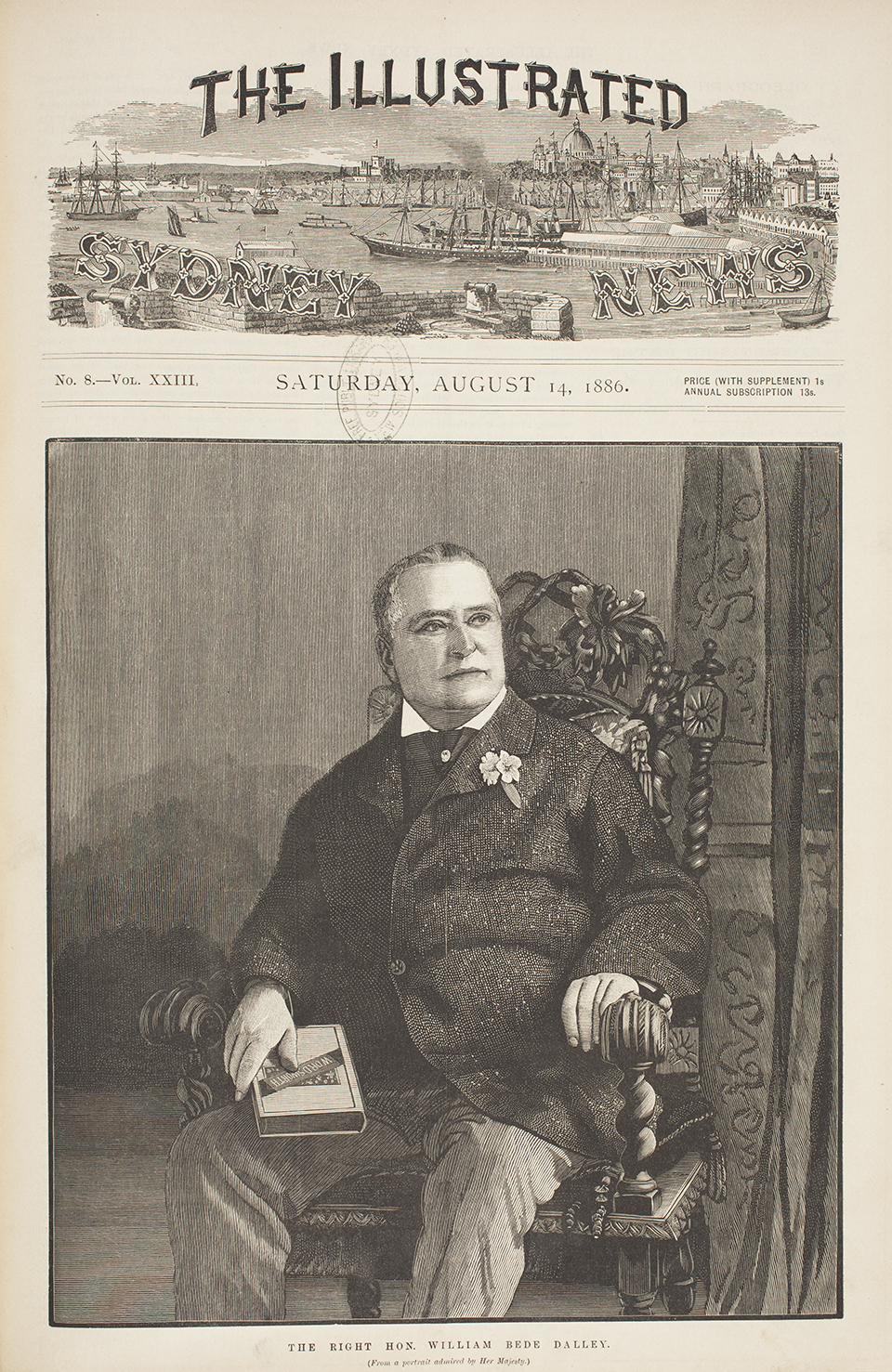

Moran was to preside over Sydney Catholics for 26 years, and in 1885 became Australia's first Catholic Cardinal. Moran was a complex figure; he supported 'Home Rule' but always emphasised how Catholics in Sydney had prospered in the British Empire. In 1901, the year of Queen Victoria's death, he rose at the St Patrick's Day banquet to propose a special toast to Her (late) Majesty. Moran was particularly keen to see Australian Catholics take what he regarded as their rightful place as leaders of Australian society. He [media]surrounded himself with such prominent Catholics as William Bede Dalley, the first Australian political leader to be made a British Privy Councillor, whose statue stands in Hyde Park opposite St Mary's Cathedral.

Australia's first Cardinal was also good at staging events which pointed out the contribution Sydney's Catholics had made to their city. In 1901, the year of Federation, the St Patrick's Day parade had no green bunting and riotous drinking, but featured instead a solemn procession through the streets from St Benedict's church in Broadway to St Mary's Cathedral. Carried in procession through the inner city were the remains of Sydney's famous early Catholic prelates – Englishman John Bede Polding, first Catholic Archbishop of the city, and three Irishmen, Archdeacon John McEncroe, Archpriest John Joseph Therry and Father Daniel Power. A large crowd watched, many of whom were not Catholic but had come along to pay tribute to 'great pioneer citizens'. The graves of these men, suitably inscribed, can be seen in St Mary's Cathedral crypt to this day. [36]

[media]But Moran did not always get things his own way. In Waverley Cemetery is a monument, dedicated in 1900, to the rebellion in Ireland of 1798, perhaps the greatest and most bloody uprising against British rule in Ireland. Between 1799 and 1802, many of the rebels were transported to Sydney and, in 1806, five rebels referred to as 'state prisoners' or 'exiles' arrived on the Tellicherry. They were all from County Wicklow and, after the rebellion was put down in 1798, they had successfully evaded capture in the mountains of that county for five years. Their leader was Michael Dwyer and his fame as a defiant Irish rebel, while little in evidence in New South Wales, hung around his name for the rest of the century. Dwyer's remains, and those of his wife Mary, were disinterred from Devonshire Street Cemetery, Sydney, in 1898 when that land was reclaimed to build Sydney's Central Station. Initially Moran refused to have the bodies brought to St Mary's, for he regarded Dwyer as the sort of violent Irish rebel from which respectable Catholic Sydney should disassociate itself.

[media]Faced with considerable pressure from his flock, Moran relented and allowed the Dwyer remains into the cathedral where he himself preached a eulogy to the dead rebel. The coffins were then taken through the streets of Sydney through an estimated crowd of more than 100,000 to a grave which became the centrepiece of the new 1798 Memorial, one of the largest, most elaborate and complex monuments to that event anywhere in the world. So while they followed Moran in most matters relating to their religion, education and general advancement in colonial Sydney, the city's Catholics of Irish descent, identified themselves just as strongly with this Wicklow rebel who had been forced by an alien government to live among them in the colony's early years. [37]

[media]During the nineteenth century, Sydney developed, according to James Jupp in another article in this dictionary, as an 'English' city. Clearly it also acquired a distinctive Irish tinge. Increasing numbers of Catholic churches, convents, schools, and other charitable institutions, spoke of the presence of a culture which saw itself as Catholic Australian and set apart from the city's predominant Anglo ethos. Along with the 1798 Memorial, unveiled on Easter Sunday 1900, these structures indicated as eloquently as any of Sydney's statues or monuments, that perhaps a third of Sydney's inner-city population never thought of somewhere called 'England' as home.

References

Philip Ayres, Prince of the Church: Patrick Francis Moran, 1830–1911, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne, 2007

Census of New South Wales 1828, 1846, 1851, 1861, 1871, 1891 and 1901

Malcolm Campbell, Ireland's New Worlds: Immigrants, Politics and Society in the United States and Australia, 1815–1922, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 2008

'John O'Brien'(Father Patrick Hartigan), On Darlinghurst Hill, Angus and Robertson, Sydney 1984

Patrick O'Farrell, The Irish in Australia, New South Wales University Press, Sydney, 1987

Oliver MacDonagh, 'The Irish in Australia: A General View', in Oliver MacDonagh and WF Mandle (eds), Ireland and Irish Australia: Studies in Cultural and Political History, Croom Helm, London, 1986, pp 155–176

Richard E Reid, Farewell My Children: Irish Assisted Emigration to Australia, 1848–1870, Anchor Books, Spit Junction NSW, 2011

James Waldersee, Catholic Society in New South Wales 1788–1860, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 1974

Notes

[1] For crew list of the Endeavour, 1768, see 'Ships and crews', Captain James Cook 1728–1779 website, http://www.captcook-ne.co.uk/ccne/themes/shipsandcrew.htm, viewed 8 November 2012

[2] 'Irish First Fleeters' in Molly Gillen, The Founders of Australia, Library of Australian History, North Sydney, 1989, Appendix 3, pp 421–422

[3] Voyage a la Nouvelle Galles du Sud, a Botany-Bay, au Port Jackson, en 1787, 1788, 1789 / par John White ; traduit de l'Anglais, avec des notes critiques et philosophiques sur l'histoire naturelle et les moeurs par Charles Pougens, Chez Pougin, Paris, 1795

[4] For an online database of all the Irish convicts transported to Sydney see 'Irish Convicts 1788–1849', compiled by Peter Mayberry at http://members pcug org au/~ppmay/convicts htm. The Irish convict statistics are from an analysis of the material on Mayberry's database

[5] For a full, and objective, account of the Castle Hill rebellion see Anne-Maree Whitaker, Unfinished Revolution, United Irishmen in New South Wales 1800–1810, Crossing Press, Sydney, 1994

[6] James Waldersee, Catholic Society in New South Wales 1788–1860, Sydney University Press, 1974, p 103

[7] The full text is beneath the Governor Bourke statue outside the old entrance to the State Library of New South Wales in Shakespeare Place, Sydney

[8] From Governor's Lachlan Macquarie's speech at the laying of the foundation stone of old St Mary's Cathedral, 29 October 1821, in Eris O'Brien, Foundation of Catholicism in Australia, Life and Letters of Archpriest Therry, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1922, vol1, p 48

[9] 'Opening of St Patrick's Church, Sydney', Morning Chronicle, 20 March 1844

[10] 'Dean Sheridan', in 'John O'Brien' (Father Patrick Hartigan), On Darlinghurst Hill, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1984, p 63

[11] There are many publications concerning the histories of the various Irish religious orders who came to Sydney and New South Wales in the nineteenth century, and the institutions they established, but for example see Errol Lea-Scarlett, Riverview, A History, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1989 and Madeleine S McGrath, These Women: women religious in the history of Australia, Sisters of Mercy, Parramatta 1888–1988, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1989

[12] For Henry Parkes's attitude to Irish Catholic immigration, see Irish immigration: speech of Henry Parkes delivered in the Legislative Assembly of New South Wales on the second reading of "A bill to authorise and regulate assisted immigration", Oct 14th, 1869, SE Lees (Printer), Sydney, 1869

[13] For the ideals and objectives of the Hibernians, see Patrick O'Connor, The Hibernian Society of New South Wales 1888–1988, undated, c1980, p 15

[14] 'Hibernian Society's Picnic', Sydney Morning Herald, 27 December 1890, p 8 ; 'A Riot at Chowder Bay', Bathurst Free Press, 7 October 1890, p 3

[15] Patrick O'Connor, The Hibernian Society of New South Wales 1888–1988, undated, c1980, p 37

[16] Eneas Mackenzie, Memoirs of Mrs Caroline Chisholm, with an account of her philanthropic labours in India, Australia and England, to which is added a history of the Family Colonization Loan Society, Webb Millington, London, 1852, p 104

[17] Evidence of Registry Office Keeper, Marion Pawsey, in 'Select Committee on the Conditions of the Working Classes of the Metropolis', Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, 1859/1860, vol 4, pp 115 and 117

[18] Evidence of Registry Officer Keeper, Robert Haigh, 'Select Committee on the Conditions of the Working Classes of the Metropolis', Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, 1859/1860, vol 4, p 112

[19] Ship's Papers, Ocean Empress, arrived Sydney 18 January 1864, State Records NSW, 9/6284

[20] Richard Reid, 'Aspects of Irish Assisted Emigration to New South Wales, 1848–1870', PhD thesis, ANU, 1992, vol 2, p 52, figure 3.5, 'UK Regional Origins of Females in Hyde Park Barracks, May 1855'

[21] 'Immigration Agent's Report', 1854, Votes and Proceedings, New South Wales Legislative Council, 1855, vol 2

[22] See Richard Reid, 'A place for the friendless female –The Sydney Immigration Barracks, 1848–1886', in M Metzke (ed), Giving History the Justice it Deserves, Proceedings of the Royal Australian Historical Society with Affiliated Societies, Sydney, 1993

[23] Report for the Select Committee on Irish Female Immigration, Government Printer, Sydney, 1859, pp 5–6

[24] For a full description of the memorial see Irish Famine Memorial website, http://www.Irishfaminememorial.org, viewed 8 November 2012

[25] There are number of good accounts of this event but see 'The O'Farrell Incident', Chapter 3, in Keith Amos, The Fenians in Australia, 1865–1880, New South Wales University Press, Kensington NSW, 1988

[26] 'Meeting of the Loyal Orange Institution', Sydney Morning Herald, 25 March 1868, p 3

[27] See for example 'Schomberg Orange Lodge No 2 ', under 'Meetings', Sydney Morning Herald, 16 December 1869, p 1

[28] 'Orange Celebration', Sydney Morning Herald, 13 July 1886, p 5

[29] For a comprehensive account of the Frazer fountains see 'Drinking Places' in 'Water, water, everywhere – a virtual historical exhibition', City of Sydney website, http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/waterexhibition/drinkingplaces/FrazerFountains.html, viewed 8 November 2012

[30] All census statistics on the nineteenth-century Irish population of Sydney, census by census from 1846 to 1901, from Australian Data Archive website, http://ada.edu.au/ada/home, viewed 8 November 2012

[31] Oliver MacDonagh, 'The Irish in Australia: A General View', in Oliver MacDonagh and WR Mandle, Ireland and Irish-Australia: Studies in Cultural and Political History, Croom Helm, Sydney, c1986

[32] Malcolm Campbell, Ireland's New Worlds: Immigrants, Politics and Society in the United States and Australia, 1815–1922, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 2008, p 95

[33] 'St Patrick's Day at Botany', Illustrated Sydney News, 14 April 1883, in Malcolm Campbell, Ireland's New Worlds: Immigrants, Politics and Society in the United States and Australia, 1815–1922, p 152

[34] 'Mr Redmond's Mission', Sydney Morning Herald, 7 March 1883, p 5

[35] For a fulsome account of Moran's arrival, see James T Donovan, His Eminence: Australia's First Cardinal, Prince of the Church and Public Man, William Brooks, Sydney, 1902

[36] 'The Irish national festival – how it was spent in Sydney', Freeman's Journal, 28 March 1901, p 23

[37] For an account of the building of the 1798 Memorial, see Richard Reid and Brendan Kelson, Sinners, Saints and Settlers – A Journey through Irish Australia, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, 2010, pp 114–116, and for Moran's attitude see Patrick O'Farrell, The Irish in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 1987, pp 238–240