The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Sydney's lost theatres

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Sydney's lost theatres

Theatres have been part of life in Sydney since 1796, and have operated on more than two dozen sites. However, Sydney has lost many of its 'live' theatres, many of them destroyed before the mid-1930s. With their loss has also gone the memory of much of the city's popular culture. Just two early theatre sites remain in use by commercial houses – The Royal and Her Majesty's (formerly Empire). [1]

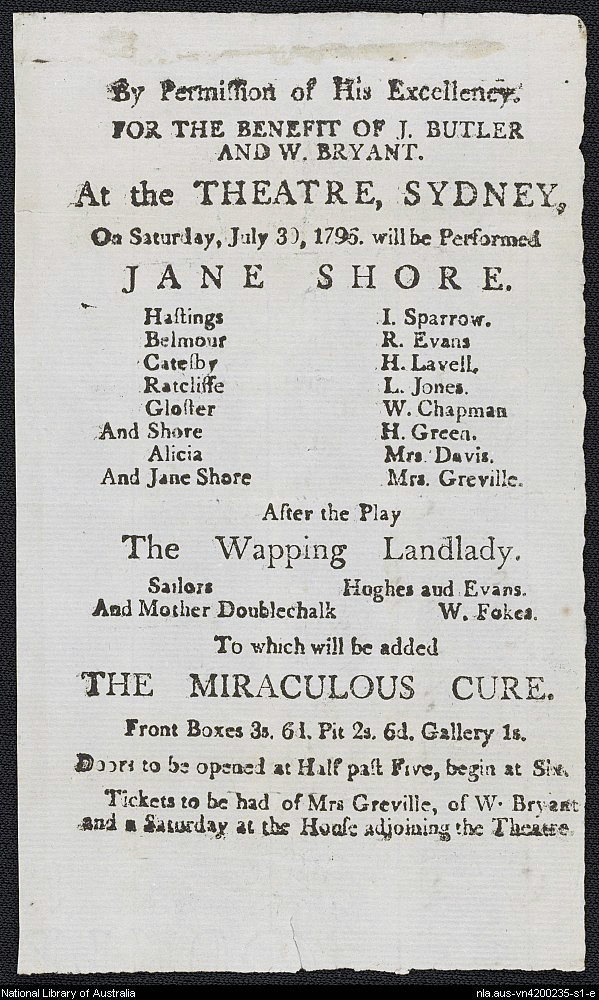

A convict theatre

[media]The first lost theatre was opened on 16 January 1796. It had been built, in Lieutenant-Governor David Collins' words, by 'some of the more decent class of prisoner' and the convicts had 'fitted up the house with more theatrical propriety than could have been expected, and their performance was far above contempt'. [2] It is generally known as Robert Sidaway's theatre, he being either the prime mover in it establishment, its owner or manager. [3]

[media]The exact location of the theatre is unclear, but it is thought to have been either at Bells Row (Bligh Street), or High (George) Street near Jamieson or Hunter Streets. It is likely to have been a rather primitive timber slab-sided small hall or shed with perhaps a stepped floor – being the pit there would be the 'front box' over or behind, which commenced a gallery. [4] Occasional performances were held until the arrival in 1800 of Governor King who objected to alleged abuses, such as convicts robbing houses while their occupants attended the theatre.

The Theatre Royal

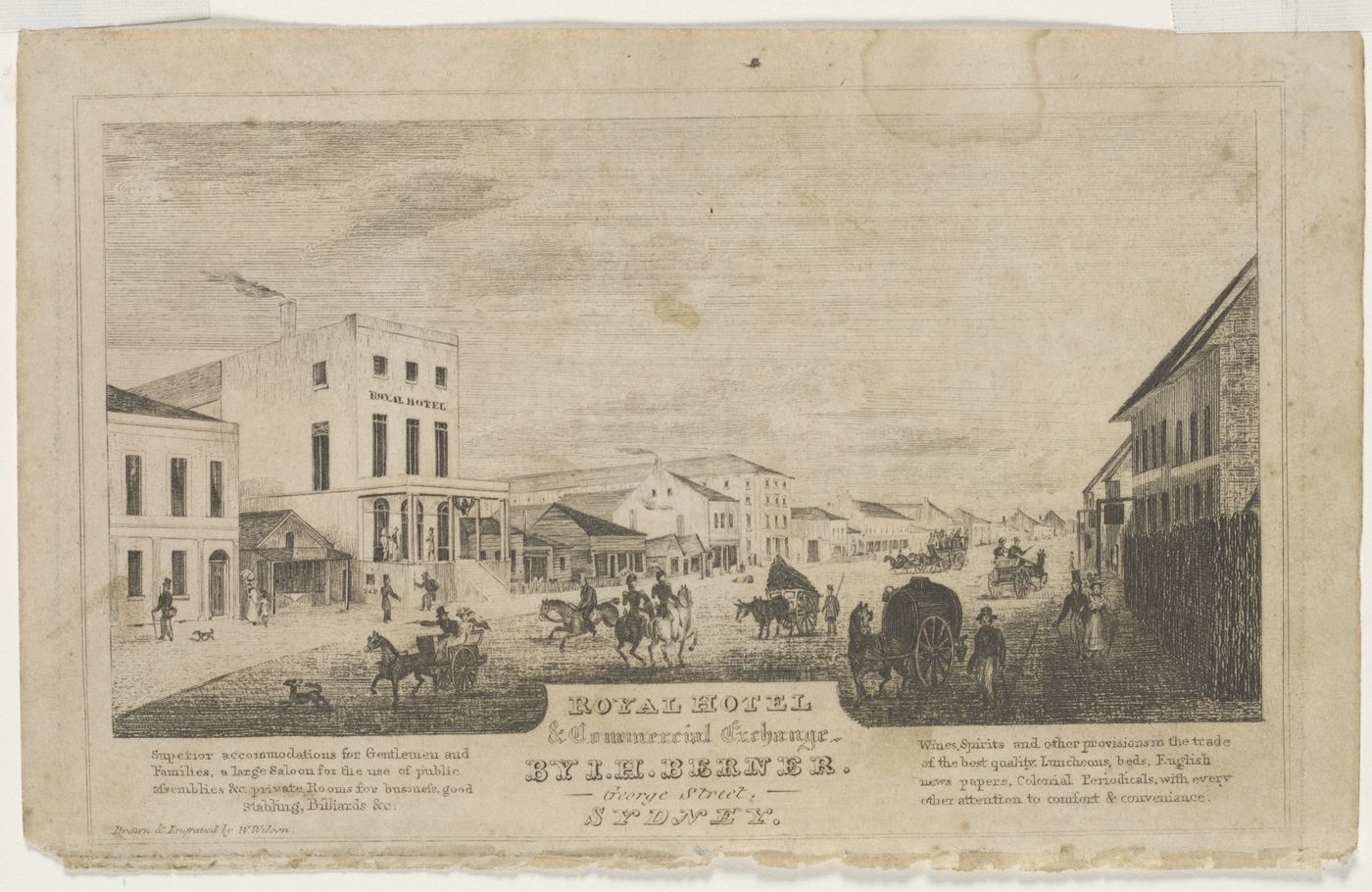

[media]The first 'permanent' theatre to be built in Sydney had a remarkable history. It was originally built as the second level of a brick four storey grain warehouse in 1826 by Barnett Levey, but opened as the Theatre Royal in 1833. The ebullient, somewhat erratic owner carried on a running verbal battle with Governor Darling in his effort to obtain a licence. In the meantime, he constructed the Hotel Royal fronting the warehouse in George Street and was bankrupted. The mortgagors had architect-builder John Verge reconstruct the theatre in two levels of the warehouse. It contained a pit and three timber panelled tiers above, of boxes, family circle and gallery. Its proscenium contained two doors onto the stage apron in the conventional Georgian Regency style of the day. [5]

[media]The Royal was Sydney's only theatre until 1838 when Joseph Wyatt, haberdasher, built the Royal Victoria in Pitt Street. It was Sydney's first large theatre and would have been the envy of a major provincial English city. Levey's Royal burnt down in 1840, leaving the Royal Victoria without opposition, though not for long.

Actor-managers and new theatres

Apart from the theatrical entrepreneur Wyatt, a number of actors took up theatre management in the capital cities and occasionally toured the country. Samson Cameron was known in Sydney, Hobart and Melbourne, and Conrad Knowles also travelled frequently. The latter took over the Australian Olympic Theatre in Hunter Street soon after its proprietor received its first theatrical licence on 25 January 1842. [media]The Australian Olympic Theatre was little more than an elaborate tent draped inside with decorative fabric and lit by gas. Around the circle used for equestrian events was a pit (stalls) and boxes; a small stage was tacked on to the perimeter, all much the same as the first enclosed amphitheatre built by Philip Astley in London in the late eighteenth century. This theatre lasted just six months but was the first of a line of circus-amphitheatre type buildings, culminating in the Hippodrome, which built by Sydney City Council for the circus entrepreneurs the Wirth Bros in 1916. This was rebuilt as the Capitol cinema in 1927–1928. [6]

Knowles returned to the Royal Victoria but another actor-manager, Joseph Simmons, attempted to break Wyatt's monopoly at the 'Vic'. He opened the Royal City Theatre, a one-level theatre, probably in a small warehouse, in Market Street in May 1843. By July, after installing a second tier of boxes, the proprietors were insolvent. The Royal City Theatre remained licensed for plays and entertainments until May 1850 but performances, if any were rarely advertised. It was then occupied by a furniture warehouse which vacated the premises for one week only in 1856 for the purposes of 'Grant Musical Entertainments'.

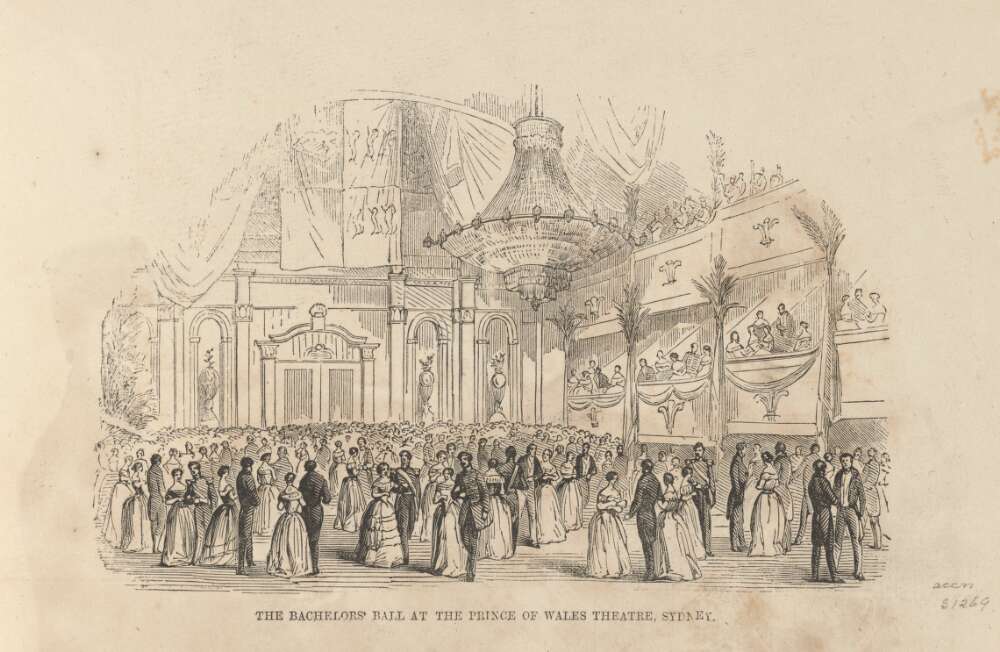

[media]From mid-1843 until 1855 the theatrical monopoly remained with Wyatt and his successors at the Royal Victoria, with the exception of a few circuses and halls and hotels that were used for musical and general entertainments. In 1855 Wyatt built the Prince of Wales in Castlereagh Street. His former 'Old Vic', as it became affectionately known, was a very important theatre in Australia. It was the first large theatre. It had a handsome three-storey Georgian-style façade to the fronting hotel but the auditorium was Regency style, still with doors in the proscenium. [media]It had four distinct levels of audience until 1865, when it was reconstructed more spaciously with three levels. The stage was large, being extended to a depth of 100 feet (30 metres) in a few years after its opening. [7] Fire destroyed it in 1880, leaving Sydney with three playhouses: the recently built Theatre Royal in Castlereagh Street on the site of the Prince of Wales which had been destroyed, a poor, cramped theatre in York Street and an even smaller one in King Street at the York Street corner.

Circuses and amphitheatres

John Malcolm built the Royal Australian Circus, an unroofed circus for 'horsemanship, tumbling and rope dancing', in the yard behind the Adelphi Hotel in York Street in 1850. The patrons were protected in grandstand-type accommodation appended to the rear of the hotel. Success allowed this accommodation to be extended around the sides of the performing surface which was roofed at the same time in 1856.

In the next year a stage was added, causing a name change to the Royal Australian Amphitheatre. Malcolm was back again in 1856 providing equestrian performances as well as human theatre, with Gustavus Brooke treading the boards in his tragedian roles. [media]The building was reconstructed to provide three levels of accommodation. In 1857 it returned to becoming the Olympic Circus, then there followed a season of it being a ballroom. Its chequered career continued thus with a variety of uses and name changes (Adelphi in 1869, Café Chantant in 1871, Theatre Royal in 1872) until the Queens was settled upon in 1873. Two years later it was refitted for the opening of Struck Oil with JC Williamson and his wife Maggie Moore. Their four-month season at this theatre was to inaugurate for Sydney the 100-year association with the entrepreneurial organisation affectionately known as The Firm.

The Queens was condemned as a hazard to human life and closed in 1882.

Expansion in the 1880s

The first Sydney Opera House, which was located half a block towards the harbour from 1879, was a small auditorium in a very austere building above a series of lock-up shops fronting King Street. Upon its opening the Sydney Morning Herald welcomed the lack of gallery, saying 'stamping about and the showers of playbills and more objectionable things which we have experience in other houses are impossible here'. It was used for musical comedy and as an overflow house, such as when Coppin's company was forced out of the Victoria by a fire in 1880.

[media]In 1880, with a sudden need for more theatrical accommodation, the Catholic Guild Hall in Castlereagh Street was pressed into service. It became the Gaiety. Behind a hybrid Venetian Gothic façade, the long hall was subdivided into stage and auditorium complete with proscenium boxes, a dress circle and sloping stalls laid over the old flat floor. By the 1890s it was no longer required, there then being five substantial theatres in Sydney.

Another theatre which led a rather nondescript life through the last years of the nineteenth and early years of the twentieth century was the Royal Standard, in the next block towards Central Railway. It had been the Royal Foresters' Hall before undergoing a minimal conversion to a playhouse in 1886. It occasionally presented drama but more frequently it showed variety or boxing. In 1913 it became Hugh Buckler's and Violet Paget's Little Theatre, where after matinees of the new (non-commercial) drama of Shaw, Wilde or Arnold Bennett, the audience was invited to partake of a cup of tea. [8]

[media]The much-admired Criterion also opened in 1886. The Sydney Morning Herald said it was 'a great advance on Sydney Theatres, and makes the spectator feel far nearer London than usual'. Although the audience was on three levels it was probably similarly intimate to, although larger than, Hobart's Theatre Royal. It was particularly suitable for plays – Sydneysiders saw, among other performers, Dion Boucicault and Marie Tempest as well as the spectacular productions of Oscar Asche. [9] It was purchased by the City Council in 1933 for the widening of Park Street.

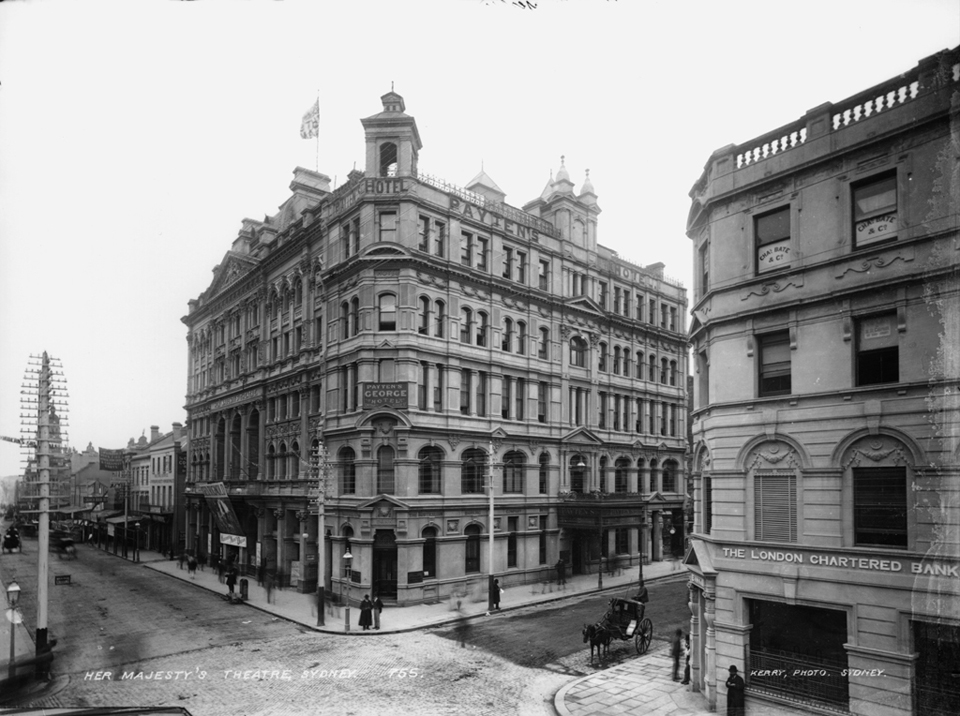

Her Majesty's Theatre and Grand Opera House

[media]In 1887 Sydney's greatest theatre, Her Majesty's Theatre and Grand Opera House in Pitt Street, was opened. It was the first theatre to have accommodation commensurate with what we expect today in front of and behind the curtain. It contained a full fly tower, a relatively new facility, having a height of 109 feet from stage basement to grid, and a new method of shifting scenes laterally on trucks. [10] Her Majesty's opened with George Rignold in a spectacular Henry V.

Her Majesty's was gutted by fire during the JCW production of Ben Hur in 1902. (The chariot race with live horses took place on a moving floor with the scenery being rolled in the opposite direction.) The theatre was rebuilt in 1903 to continue presenting the greatest names in theatre – Sarah Bernhardt, Anna Pavlova, Dame Nellie Melba, John McCormack [media]and Nellie Stewart. When the theatre closed in 1933 Gladys Moncrief, as The Maid of the Mountains, sang a special farewell on behalf of JC Williamson Theatres Ltd.

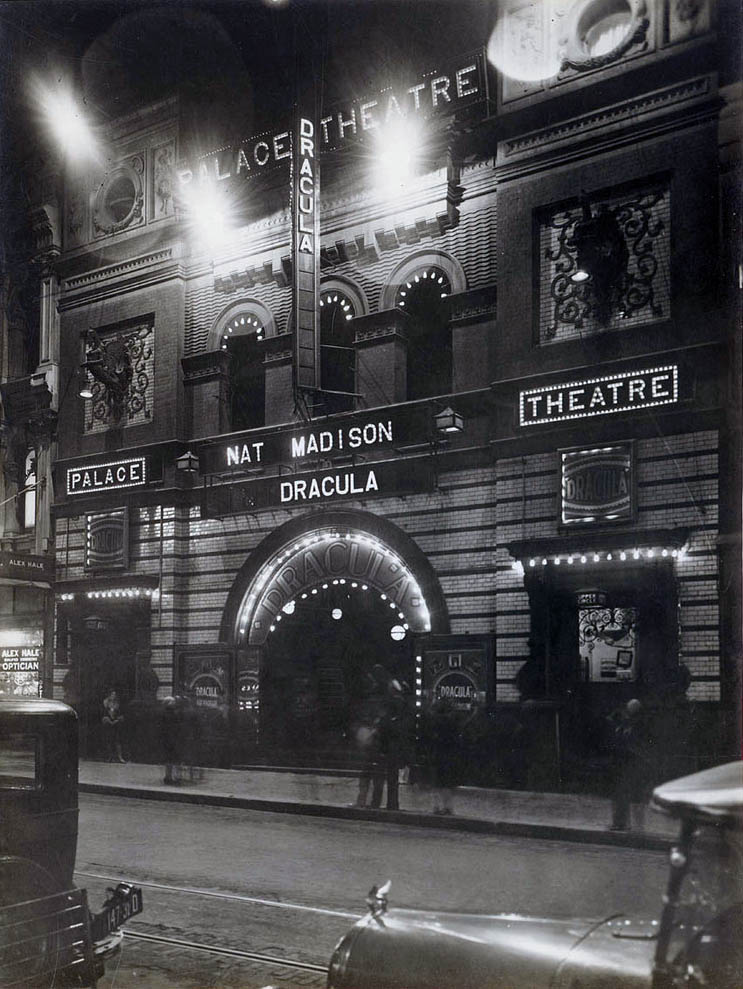

It was not until 1960 that Sydney would see a new Her Majesty's, a revamped Empire which had originally opened in 1927 as a musical comedy house. The last two theatres built in the nineteenth century were close to Her Majesty's in Castlereagh Street – The Lyceum, built in 1891–1892, and the Palace, built in 1896. [media]The Lyceum was a comfortable three-level theatre (behind another hotel), with a stage almost 60 feet square (5.6 square metres). It became a film house in 1905 then was bought by the Methodist Church, who relinquished the liquor license and converted it to a Sunday meeting hall in 1908. [11]

Twentieth century theatres

[media]The lavish St James, originally built by Ben and John Fuller, opened with No No Nanette in 1926. The Savoy, from around 1929 to 1939, housed live theatre companies, particularly Doris Fitton's Independent Theatre. The Phillip Street Theatre was located in the St James Hall, where Bill Orr received his reputation as producer of fabulous Phillip Street Revues. [12]

Gone too is the Tivoli on Hay Street near Central Railway. [media]This large theatre had commenced as the Adelphi in 1911 but was altered in 1915, becoming firstly the Grand Opera House (to be used frequently for melodrama), then the New Tivoli from 1933 to 1970. The tradition of 'Tivoli' Vaudeville shows began its state of permanency under Harry Rickards in 1893, at what originally opened as the Garrick Theatre in 1891 on the site of the Academy of Music at 79 Castlereagh Street. Rickards rebuilt the Tivoli after a devastating 1900 fire. His successors closed it in 1929 but the tradition was revived at the other end of town until 1966 when the last Tivoli show was seen. [13] The building then became the Embassy Cinema before it was demolished. The site is now occupied by Skygarden. [14]

The Alhambra was another variety theatre/music hall, although it commenced its existence as an auction room. Known first as the Haymarket Academy it was the Alhambra from 1886 until it finished up as a picture house in the 1920's. It later became a storehouse for Mick Simmons. [15]

One seldom-remembered vaudeville theatre which is lost is the National Amphitheatre, formerly the National Sporting Club. Opened in 1906 as Brennan’s National Amphitheatre it was converted by the Fuller's management into a two level theatre in 1919 and continued until 'talkie' films forced its conversion to a cinema (The Roxy) in 1930. Shortly afterwards it was renovated as the Mayfair – the rather shallow fly tower stage with multi-level dressing rooms on the northern side survived. It was demolished in 1984. [16]

Fuller's also ran the Princess, a vaudeville city theatre that had commenced life as the Bijou Picture Palace in 1908. It was bought for an extension of Marcus Clarke's department store in 1925. [17]

Of all the variety theatres the most charming and intimate was the Palace. [18] Built originally in 1896 as a Palace of Varieties its interior was a strange mixture of Moorish tinged with Gothic, containing a forest of cast iron posts. In 1924 the auditorium was rebuilt to provide an excellent house, without columns, for drama. After being a second-run cinema through most of the 1930's and World War II its traditional renaissance style of plasterwork was redecorated by Hoyts in antique cream, while the wall panels had their fabric replaced with crimson damask. It served for a short time as a first-run English film-house before returning to being a live theatre for such shows as Present Laughter and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf. It was much loved by audience and performers alike, although it was a fire hazard and the cooking smells wafted in from the kitchens of Adams Hotel next door. It closed and its fittings were auctioned off in January 1970 before its demolition to make way for the ubiquitous redevelopment.

Sydney's lost theatres represent the loss of the memory of much of the city's popular culture.

References

Parsons, Philip with Chance, Victoria. Companion to Theatre in Australia. Paddington: Currency Press, 1995.

Notes

[1] The other large theatre still in Sydney, the Capitol, was not built until 1916, and was then known as the Hippodrome; it became a cinema under its current name in 1928.

[2] David Collins, An account of the English colony in New South Wales from its first settlement in January 1788 to August 1801: with remarks on the dispositions, customs, manners &c. of the native inhabitants of that country: to which are added some particulars of New Zealand, compiled ... from the Mss. of Lieutenant-Governor King, and an account of a voyage performed by Captain Flinders and Mr. Bass ... abstracted from the journal of Mr. Bass / by Lieutenant-Colonel Collins, digital copy, University of Sydney Library, 2003, http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit/pdf/colacc1.pdf, 370

[3] Ross Thorne, 'Sidaway's Theatre', in Phillip Parsons with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia (Paddington: Currency Press, 1995), 529–530

[4] Ross Thorne, 'Sidaway's Theatre', in Phillip Parsons with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia (Paddington: Currency Press, 1995), 529–530

[5] Ian Bevan, The Story of the Theatre Royal (Paddington: Currency Press, 1993)

[6] Ross Thorne, Capitol Theatre - A case for retention (Sydney: University of Sydney Press, 1985)

[7] Ross Thorne, 'Prince of Wales Theatre', in Phillip Parsons with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia (Paddington: Currency Press, 1995), 464

[8] Ross Thorne, 'Royal Standard Theatre', in Phillip Parsons with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia (Paddington: Currency Press, 1995), 511

[9] Ross Thorne, 'Criterion Theatre', in Phillip Parsons with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia (Paddington: Currency Press, 1995), 168

[10] All the material on Her Majesty's Theatre is taken from Ross Thorne, 'Her majesty's Theatre', in Phillip Parsons with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia (Paddington: Currency Press, 1995), 269-270

[11] Lyceum Theatre, Cinema Treasures, http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/37916, viewed 9 June 2016

[12] Stuart Wagstaff, 'Eric Duckworth, 1915-2013', The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 July 2013, http://www.smh.com.au/comment/obituaries/a-true-gentleman-of-the-theatre-20130704-2peee.html, viewed 9 June 2016

[13] Ross Thorne, 'Tivoli Theatre', in Phillip Parsons with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia (Paddington: Currency Press, 1995), 605-606

[14] Leann Richards, The Tivoli Sydney to 1910, http://www.hat-archive.com/tivoli.htm, viewed 9 June 2016

[15] Tom Fletcher, Alhambra Music Hall/Theatre, Sydney Architecture, http://sydneyarchitecture.com/GON/GON077.htm, viewed 9 June 2016

[16] Tom Fletcher, National Amphitheatre Hoyt's Mayfair Theatre, Sydney Architecture, http://sydneyarchitecture.com/GON/GON078.htm, viewed 9 June 2016

[17] Theatres/Venues: New South Wales, Australian Variety Theatre Archive Popular Culture Entertainment: 1850-1930, https://ozvta.com/theatres-nsw/, viewed 9 June 2016

[18] All the material on the Palace Theatre is taken from Ross Thorne, 'Palace Theatre', in Phillip Parsons with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia, Currency Press, Paddington, 1995, 423

.