The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Millers Point

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Millers Point

Millers Point [media]is a small suburb within the City of Sydney local government area. Today it is often thought to be a part of its neighbour, The Rocks, much to the chagrin of residents who insist on recognising its separate history and development. Very few people settled in the area before the 1830s. For decades it remained an isolated place, approached only by scrambling over The Rocks or around the shoreline from Point Maskelyne, later renamed Dawes Point, where William Dawes established an observatory and battery in the first years of European settlement. His house became a meeting place for many Aboriginal people who assisted him in recording the local language and customs. In the twenty-first century this promontory was officially given the dual name of Dawes Point and Tar-Ra, which was what the original inhabitants called it.

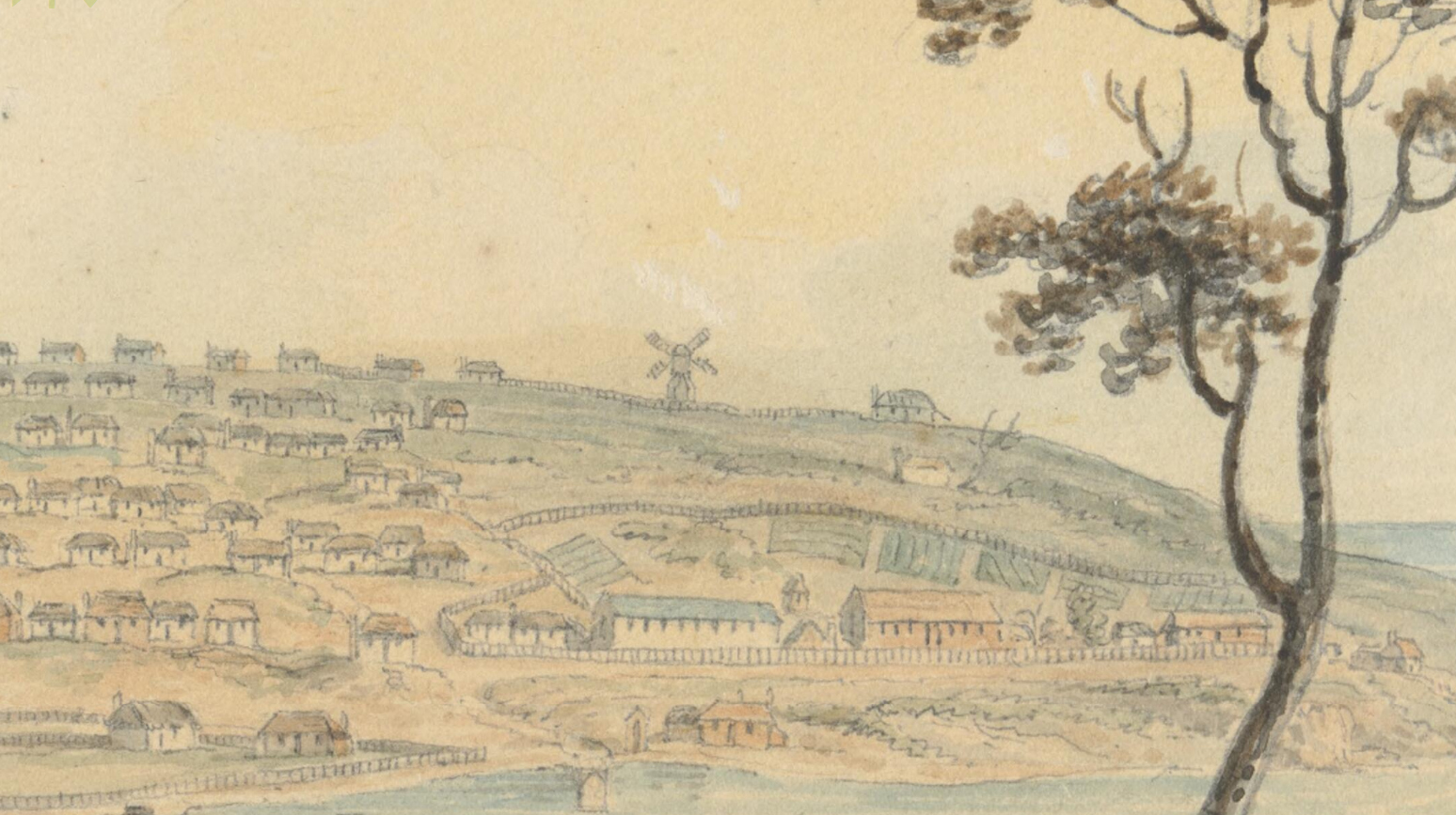

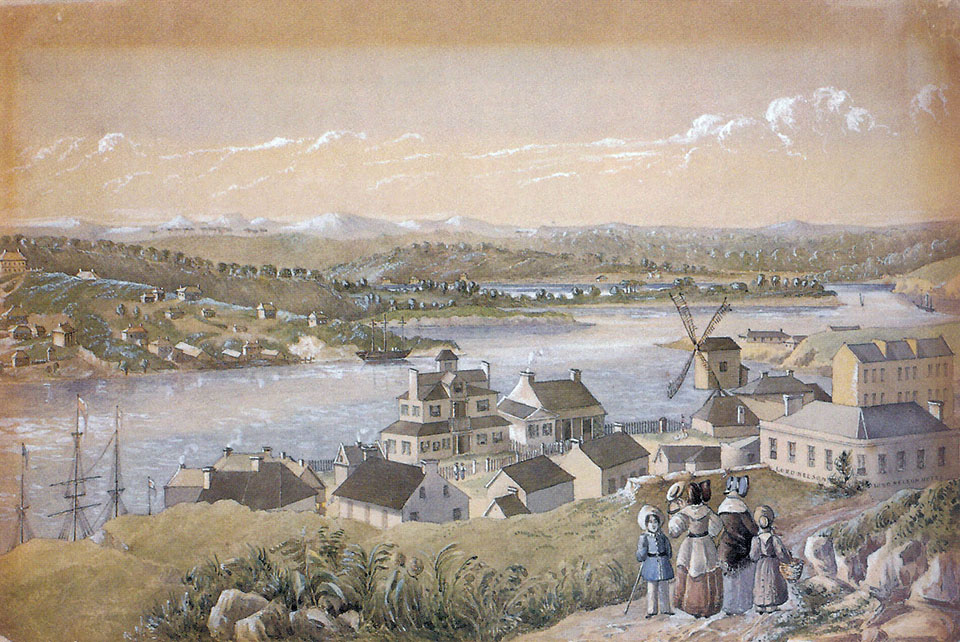

A [media]flagstaff was erected on the high ground in 1788. Here too the first government windmill was built in 1797 and, following the insurrection of Irish political prisoners at Castle Hill in 1804, work began on a fort. For these reasons the hill was variously called the Flagstaff Hill, Windmill Hill or Fort Philip, until its current name of Observatory Hill was adopted with the construction of a new observatory in 1858.

[media]Other windmills appeared, including three that were built after 1815 on the farthest point of land facing Cockle Bay. These were owned by the former convict John Leighton, known as Jack the Miller, and inspired the name Millers Point. The local people who had lived here for thousands of years called it Coodyee.

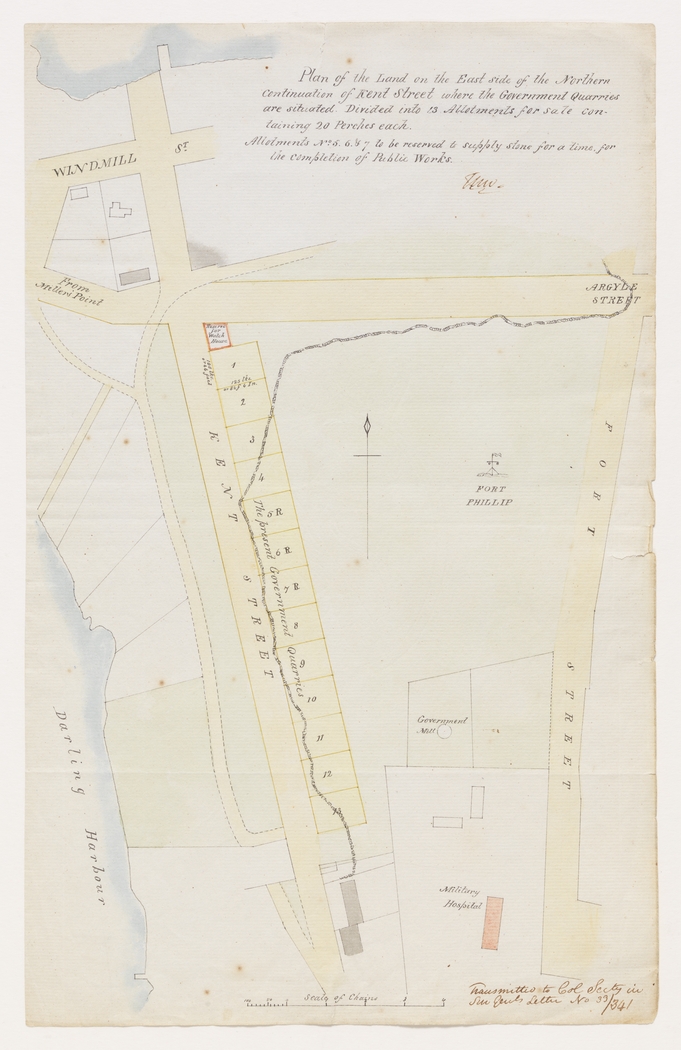

[media]Sandstone outcrops provided building material for Sydney, and the little streets of Millers Point were gradually formed through quarrying away the edges of the Flagstaff Hill, leaving the high cliffs that today front Argyle Place and Kent Street.

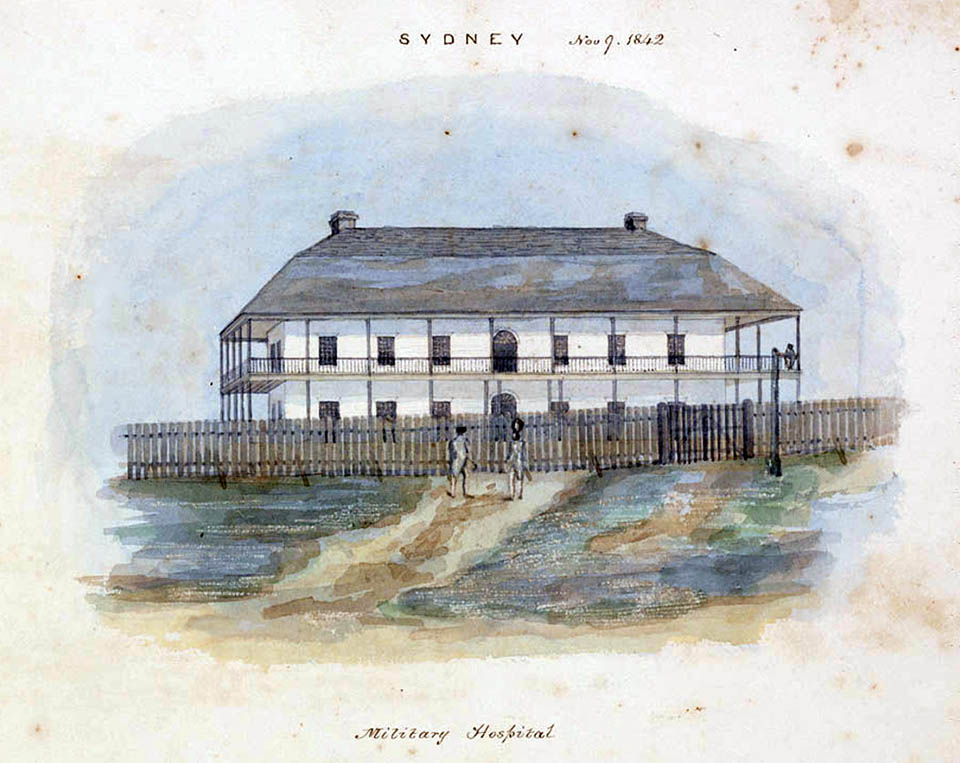

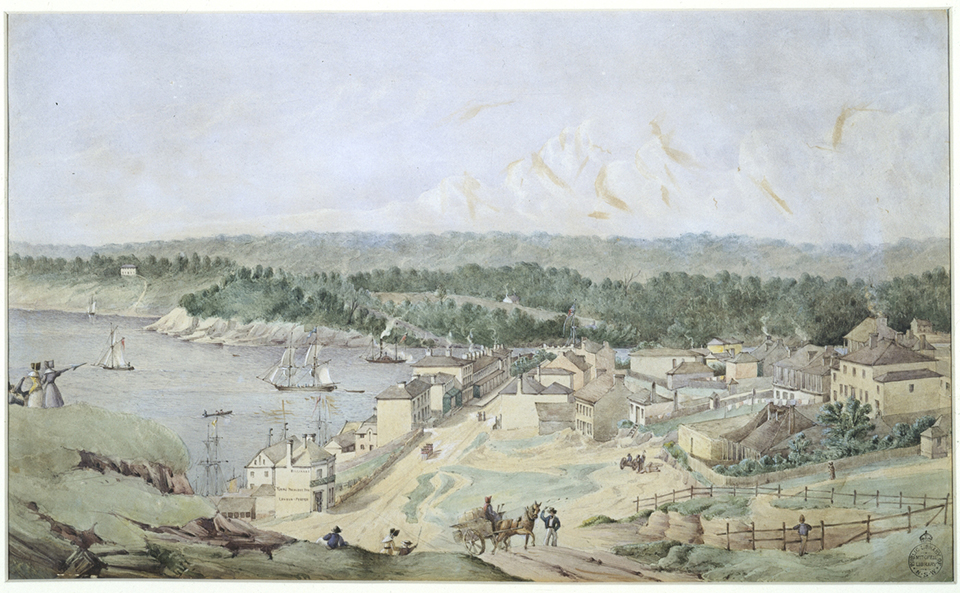

[media]A new government military hospital, built at the rear of the Flagstaff Hill in 1815, gave the area one of its first substantial buildings, but by the early 1820s there were still only about half a dozen houses in Millers Point. By then, however, space at Sydney Cove was at a premium, and wharves and warehouses began to be built alongside older boatbuilding yards west of Dawes Point. [media]The deep waters of what is now called Walsh Bay became the home of the buoyant, if odorous, whaling and sealing industry in the 1830s, and long after these industries had died out, the area remained a centre for maritime trade with China and Pacific. This area generated tales of smuggling and shanghai-ing, and persistent urban myths of secret underground tunnels connecting pubs to the waterfront, for the surreptitious movement of unwilling sailors, overproof rum and whatever else needed to evade official detection. [media]By the 1840s the terrain was lightly populated, with workers' cottages near the wharves and fine houses of wharf owners and merchants adorning the elevated streets. But with access to town still difficult, Millers Point remained isolated from and, socially, a cut above, its neighbour, The Rocks. This distinction was reduced, and access improved, once the high rocks were hewn through with the creation of the Argyle Cut in 1846.

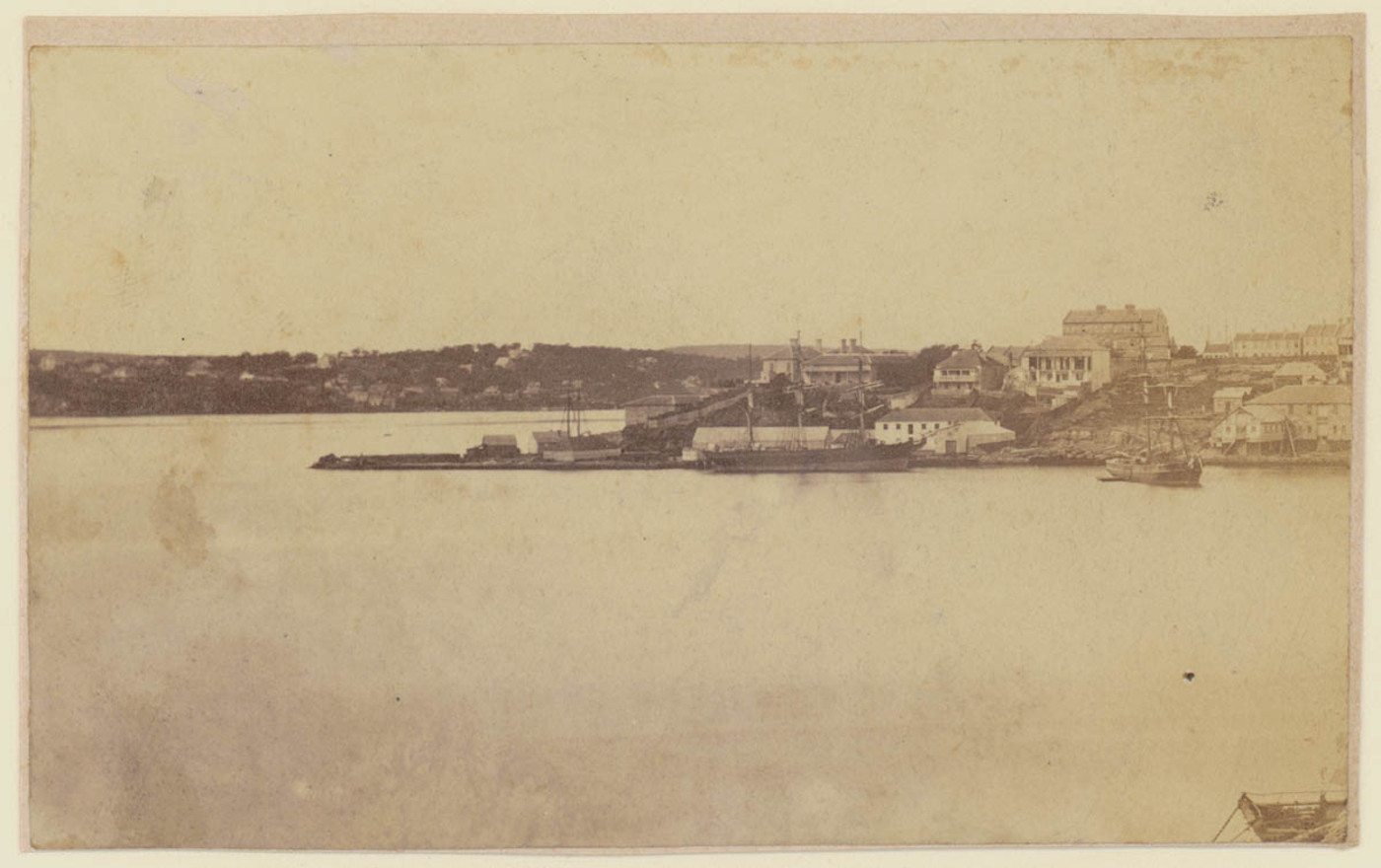

Sydney's maritime precinct

[media]By the booming gold rush period of the 1850s, Millers Point was established as the most intensely maritime area of Sydney. With the exception of the Australian Gas Light Company's works on the Darling Harbour edge of Millers Point, established in 1843, practically all employers in the area were connected to the wharves, or to the small local infrastructure of shops, hotels, doss houses and boarding houses that supported them. Family formation was low and the workforce was male-dominated, casual, highly mobile and itinerant. Here the language of the streets was not only coarser, it was spoken in more tongues, and at more hours of the day and night, than anywhere else in Sydney. On any given day, many of the people on the streets owed their allegiances to other cities in other parts of the world.

[media]The fortunes of the wharves, and hence the people, of Millers Point were tied to the rhythms of the trade cycle. Early wharfage and ships catered to a general trade, seizing on whatever product would turn a profit. When wool overtook marine products as Sydney's primary export, many of the wool ships also docked here, while the wharves around in Darling Harbour handled coastal traders. Here the tidal mudflats were steadily reclaimed so that the deep indentations that originally formed a narrow neck of the point slowly disappeared beneath a jumble of privately owned wharves.

[media]During the long economic boom from the 1860s until the depression of the 1890s, Millers Point prospered. The exuberant wool trade supported specialised firms and ships. The legendary clippers that raced to catch the first of the wool sales in England returned with passengers and goods, and by 1861 there were six large bonded warehouses in Millers Point, as well as about 400 houses and a clutch of pubs. The temporary Holy Trinity Church was remodelled by Edmund Blacket and completed in 1878. This was the approved place of worship for the military establishment, while locals, if they went to church at all, were more likely to attend St Patrick's Catholic church on Church Hill. But as the waterfront and its associated buildings expanded, and even as some new housing was constructed, the number of houses began to shrink and residential amenities to decline.

Strikes and plague

[media]The 1890s was a decade of turmoil for Millers Point. Conditions on the waterfront had always been harsh and unpredictable, but the great maritime strike of 1890, which ended with the smashing of the Wharf Labourers' Union and other associated workers' organisations, moved class warfare to a new and brutal plain. With the collapse of the wool trade and the long depression that dragged on into the new century, work was sporadic. For some these events forged a new political maturity, while others' spirits were broken.

The workers of the area and the union that bound them together [were] vilified in the Sydney press and a judgemental distance was staked out between waterfront areas like The Point and the rest of Sydney. The reputation of the area as 'rough' stems from this period. [1]

Official surveys and reports that had found little to complain about in Millers Point houses in the 1870s were by now highly critical. The wharves that had once been symbols of prosperity were derided for their insanitary conditions by the 1890s, and politicians were casting a critical eye over this privately owned infrastructure.

In January 1900 an outbreak of bubonic plague generated some heavy-handed treatment from the authorities. For a time the area was quarantined, houses were compulsorily disinfected and residents suspected of having come in contact with the disease were ferried across to the quarantine station at North Head in the dead of the night. Of greater long-term significance, the hysteria that surrounded the outbreak gave the government the excuse it needed to resume all the wharves and the streets behind them and to start a massive redevelopment project. The view that the private sector could not efficiently manage the infrastructure of the port drove some of the greatest public works ever undertaken in Sydney – the creation of modern wharves from Woolloomooloo to White Bay and the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Because the bridge was not built for decades and the process of demolition was slow, it is easy to overlook this as a reason for the post-plague resumptions, but residents had always understood this intention. In January 1902, the Daily Telegraph published a map showing the proposed 130-foot-wide (39.6-metre-wide) replacement for Princes Street, to carry the 'proposed North Shore railway' and the 'contemplated bridge over the harbour'. Princes Street belonged to The Rocks, not Millers Point, but the eventual building of the bridge had greater impact on Millers Point.

Remaking Millers Point

The initial task of the new Sydney Harbour Trust (later the Maritime Services Board) was to rebuild the wharves, but after some attempts to establish other bodies to construct new housing, this task also went to the trust. By mid-1901 it was in possession of more than 800 properties, including 553 houses, between George Street in The Rocks and Kent Street in Millers Point and behind Darling Harbour. For the next decade this meant only a change in landlord for most people, as priority was given to waterside reconstruction and to bringing the tramlines from George Street into Millers Point. Millers Point became a huge building site, and up to 1,000 men would congregate at the corner of Argyle and Kent streets in the morning, hoping to be called up for a day's labouring. The first wharves to be rebuilt were replacements for the larger private owners, such as Dalgety's on the point, who leased them back on completion.

[media]In 1909 the huge task of cutting down cliffs, reorganising the pattern of the roads and constructing large finger wharves began. The work was slowed by shortages of materials and labour during World War I but, when the scheme was finally completed in the 1920s, these cutting-edge public works had created a modern industrial landscape. Double-decked wharves were connected via road bridges that allowed entry and transfer directly to bond stores at two levels along newly created Hickson Road at Walsh Bay. Robert Hickson chaired the Sydney Harbour Trust from 1901 to 1912. Henry Walsh was the trust's chief engineer. Hickson Road continued around to Darling Harbour, where a link to Sussex Street was frustrated for years because the gas works stood in the way. Eventually these roads did join, but the planned railway along this road, connecting Walsh Bay with the goods yards in Ultimo, was never built.

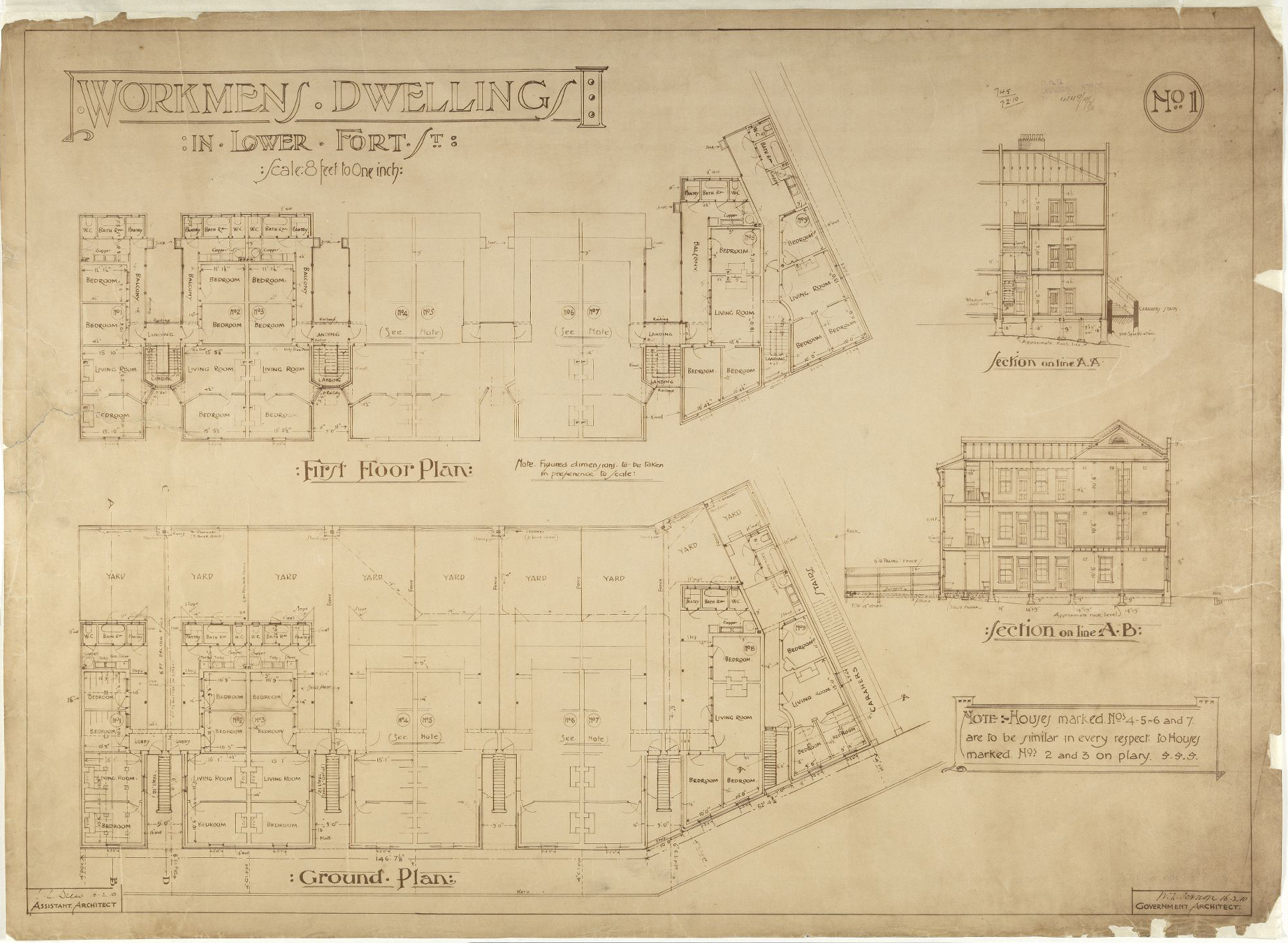

Sydney's first public housing

[media]By the 1920s whole streets had disappeared, new cliff faces had been created and hundreds of houses were replaced, though there were never as many as there had been in 1900. Quarrying to sea level along the Darling Harbour stretch of Hickson Road resulted in the creation of High Street, where the largest concentration of Sydney Harbour Trust residential buildings took shape from 1910, all with wonderful views across the harbour to Balmain. These houses, along with a kindergarten, a group of red brick shops in Argyle Street and the large red brick hotels such as the Palisade provided a coherent set of modern buildings which contrasted boldly with the retained older stock of sandstone cottages, pubs and painted terrace houses built in the nineteenth century.

[media]The trust allocated housing to maintain its own workforce, not according to need. Thus twentieth-century Millers Point, despite its village atmosphere, became something akin to a company town, with the company being the state. As the primary interest of the trust was managing the Port of Sydney, it turned a blind eye to the residents' 'home improvements' and to the unofficial system of passing on housing to friends and relatives, as long as the rents were paid and the occupants provided labour for the wharves. And as everyone did work on the wharves, Millers Point became a very close-knit little community. The practice of informally inheriting housing continued until the end of the 1980s, when the work of the port had been wound down and the houses were passed to the Department of Housing. This had significant consequences for the social and residential mix of Millers Point.

The decline of the wharves

With the twentieth century came increased differentiation of tasks on the waterfront and divisions between the men who worked on the wharves and on the ships. Much of the drama of the emergence of an organised Waterside Workers Federation in 1902 was played out in places such as Millers Point. There was always something to disrupt the smooth running of the waterfront. As the century wore on, ships became larger and less frequent, resulting in uneven work availability. During the depressed 1930s they came even less often. It was all too common to see large numbers of men jockeying for limited numbers of jobs at designated pick-up points.

They'd go to Millers Point pick up at 8 o'clock. There were hundreds of men down at Central Wharf … The bloke would come out and he'd get on a box and say 'you, you, you and you'. They were bloody hard times. If they never got a job, they'd have to go to Pyrmont for the next pick up. They'd run, or run-walk. You couldn't run all the way. Then if they missed that one, they'd walk over to Woolloomooloo. Things were destitute. [2]

Domestic life was tied to the uneven rhythms of the working day, and as shifts might extend to 24 hours, or even stretch into days, social activities centred on the home, the local pubs and the church. Men who had wives to supply home comforts, and children to carry hot meals to the wharves, were more likely to cope than men who did not. And while many of the surnames in Millers Point signified wide-ranging maritime origins, the women were strongly tied into the local society. There is some evidence that traditional social customs, often with Irish origins, lasted longer in Millers Point than in many other places in Sydney. [3] The construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, completed in 1932, strengthened the symbolic and physical barrier between Millers Point and The Rocks, while the preference for suburban living that the bridge to the north shore represented made a place like Millers Point very passé.

After the 1920s very little change occurred in the built fabric of Millers Point for many decades. The city electoral roll for 1947 recorded a population of 'occupiers', with no 'owners living elsewhere'. Even the couple of individuals with non-maritime occupations – the rector at the Garrison Church and the government astronomer, in residence on Observatory Hill – did not own their houses. With a population of around 1,500 adults, almost two-thirds of them male, the local branch of the Labor Party had over 200 members, and the only candidate at election time who could nudge down the Labor vote was one who was further to the left. In the state election of 1953, when the electorate voted 68 per cent for the Labor candidate, the Millers Point booth returned a tally of 90 per cent. At the next election in 1956, the Labor vote sank to 64 per cent, with 26 per cent going to other left-wing candidates.

But by the 1960s, things were changing. Radio call-ups for work and private car ownership loosened the nexus between living and work for wharfies. The population was aging, with attendance rising at the Harry Jensen Activity Centre next to the old Abraham Mott Hall (formerly the Coal Lumpers' Hall) in Argyle Place, and enrolment down at Fort Street Primary School, from 272 in 1955 to 48 by 1975. At this date Fort Street Girls High School, the remaining part of the city's oldest secondary school, moved to rejoin its male counterpart, which had moved to Petersham in 1916. The site on Observatory Hill, originally the old Military Hospital, then the Fort Street Model School from 1849, became the headquarters of the National Trust of Australia (NSW).

Heritage and high culture

By the 1970s the National Trust was joining forces with radical trade unionists and community groups to halt government-driven high-rise development in The Rocks, and a new practice of officially referring to Millers Point as 'West Rocks' was pounced on by locals anxious to distance themselves from this development push. By the time community pressure and economic slowdown had taken the steam out of the plans of the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority and the heritage values of the area were being widely recognised, not much redevelopment had occurred in Millers Point. But there had been some, and initially heritage significance was defined to include only nineteenth-century structures. The early twentieth-century finger wharves in Darling Harbour were converted into roll-on-roll-off container terminals in the 1960s. At the Point, the 1903 Dalgety's wharf was removed, houses were pulled down and a large Harbour Control Tower was built in Merriman Street in 1974.

Nevertheless, much of the trust's infrastructure remained intact, and was gradually recognised as highly significant in its own right. The decision to move major port activities to Botany Bay from the mid-1970s left Millers Point with excess wharfage, but also with a lot of people willing to champion its unique heritage position as a relatively untouched nineteenth- and early twentieth-century port enclave. Numerous reports began to extol the value not just of individual buildings, but of the whole area. But the heritage perspective was a minority one, and many politicians viewed the disused wharves and sheds as financial millstones around the neck of cash-strapped governments.

From the mid-1970s wharves 4/5 were used as a cultural complex by various performance companies, but much of the building stock was deteriorating. The following decades were characterised by temporary uses, legal battles and public protests over the future of Millers Point. Here and there, bits of this public land were sold to the private sector. The handover of administration of the houses to the Department of Housing in the 1980s challenged the old social ways. Finally, in 1999, the state government passed enabling legislation to redevelop much of the area. [4]

Against sharp public protest, one of the Walsh Bay finger wharves was demolished and rebuilt as private residential space. The apron of the wharves was developed with restaurants and exhibition spaces. New houses were built, and a state-of- the-art drama and dance venue on Hickson Road provided the Sydney Theatre Company with a permanent home. Below Ferry Lane, an area that had remained unbuilt on since the early twentieth century, was developed into a park, with signs telling the history of the area. It has retained the colloquial name long attached to it, the Paddock.

What's in a name?

In recent years Millers Point, a place long shunned by most Sydneysiders, has become attractive to wealthy investors. Pressure on the public housing is intense, and the amount of the historic fabric of Millers Point that should be retained is constantly under debate.

With gentrification came the desire for names that were disconnected from the less respectable past. In 1993 the eastern section of Millers Point, including some of the Walsh Bay wharves, was formally listed by the New South Wales Geographical Names Board as a separate suburb named Dawes Point. This arbitrary division of an area that had always been tightly connected geographically and in all of its economic and social activities did not reflect local understandings of what constituted Millers Point.

Plans for a massive redevelopment of the Darling Harbour wharves and the Hickson Road area below High Street will transform this part of Millers Point. The official renaming of this yet-to-emerge place as Barangaroo is just the most recent indication of a desire on the part of the developers to obliterate the time-honoured name of Millers Point.

The name Barangaroo commemorates the wife of Bennelong. Her people lived on the north shore, not around Darling Harbour, and the Aboriginal name for this stretch of water is Gomora.

References

Shirley Fitzgerald and Christopher Keating, Millers Point, The Urban Village, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991

Notes

[1] Shirley Fitzgerald and Christopher Keating, Millers Point, The Urban Village, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, p 61

[2] James Gaby, The Restless Waterfront, Antipodean, Sydney, 1974, p 28

[3] Shirley Fitzgerald and Christopher Keating, Millers Point, The Urban Village, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, pp 93–96, 102–03

[4] Walsh Bay (Special Provisions) Act, 1999 (New South Wales)

.