The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Children

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Children

Writing in the Bulletin in February 1898, the poet Victor Daley lamented that it would take up to 500 years for a distinctive Australian 'child-literature' to surpass the European influences so evident in the everyday singing games of children. [1] 'Wrong!', wrote 'J.A.P.', reporting that his daughter and her friends, pupils at a Sydney public school, accompanied their games with the chant:

Johnny and Jane and Jack and Lou,

Butler's Stairs through Woolloomooloo;

Woolloomooloo, and 'cross the Domain,

Round the Block, and home again!

Heigh, ho! tipsy toe,

Give us a kiss, and away we go. [2]

A second correspondent consigned a further 'Woolloomooloo (Sydney) classic' to print:

Bake a puddin',

Bake a pie,

Take 'em up to Bondi;

Bondi wasn't in,

Take 'em up to black gin; [sic]

Black gin took 'em in –

Out goes she! [3]

As these examples demonstrate, the playlore of Sydney's white children combined the traditions of European chanting games with their own understandings of places, social attitudes and historical experiences.

From the early colonial period, adult commentators viewed the development and distinctiveness of the colonial child as a barometer of the extent of social progressiveness and adaptation within Australian society more generally. Indeed, within the rhetoric of Empire and burgeoning nationalism in the late nineteenth century, the racialised metaphor of the white child was often used to represent Australia. Popular depictions of the childlike nation included a vulnerable fair-haired girl and the Bulletin's innocent but knowing cartoon figure, the 'Little Boy from Manly'. [4] Such symbolic imagery has persisted, with the history of settler Australia portrayed through the figure of a young white girl in the extravagant performance of nationhood opening the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games.

Historical interest in children and in the ideological construction of childhood has been relatively limited in Australia. With the exception of studies of children's folklore and play, the focus has been on the ways adults have understood and controlled children – for instance through education and welfare policies – rather than the experiences and viewpoints of children themselves. [5] Indeed, state intervention in the lives of European and Indigenous children and in family formation more broadly, has been ongoing and comprehensive in New South Wales from the colonial era. While children have always comprised a substantial proportion of the overall population of Sydney, their voices are absent [media]or muffled in many historical records.

This article provides a brief overview of some of the experiences of children in Sydney since British colonisation. Over this time, there has been a shift in the adult expectations of children and in the age when childhood is perceived to end. In line with the classifications used in historical data, I have generally defined children as those aged between 0–14 years, although a more common definition today would be 0–12 years. [6] One of the most striking features in the history of childhood has been the increasingly prominent recognition of adolescence as a distinct (and extendable) life stage that buffers the child from the adult.

Aboriginal and European children in 1788

Almost 50 British children, whose parents were marines or convicts, were among the First Fleet when it sailed into Sydney Cove in January 1788. They ranged from infants to those nearing the then legal adult age of 14 years. In addition, a small number of convicts were children when they were sentenced to transportation. [7] After the British party disembarked on the land of the Eora people, Marine Watkin Tench was in the company of a seven-year-old boy when he experienced his first cross-cultural encounter. He recorded that the Aborigines examined the boy very gently, and were fascinated by his white skin. But they kept their own children well away from the British camp. [8]

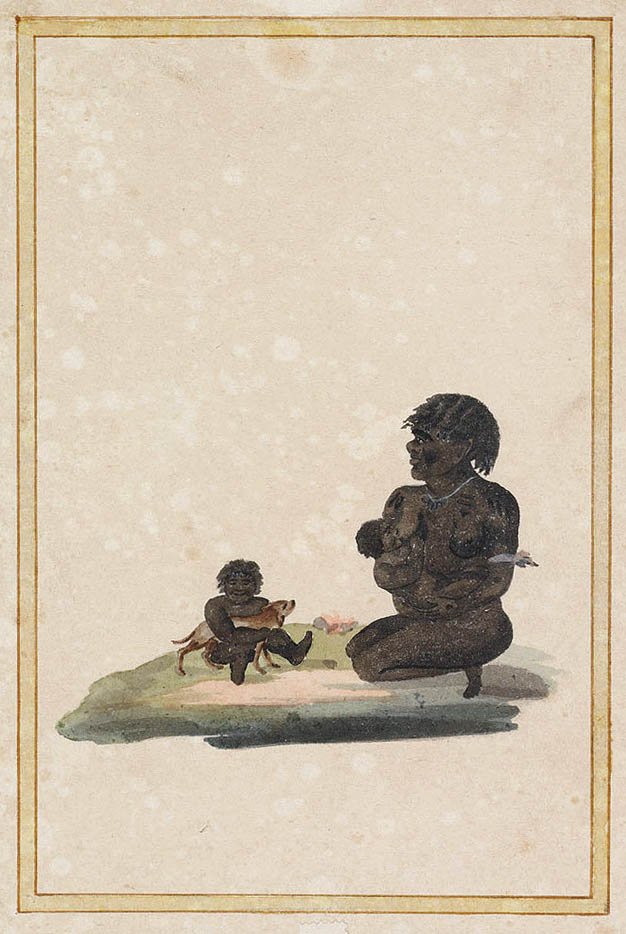

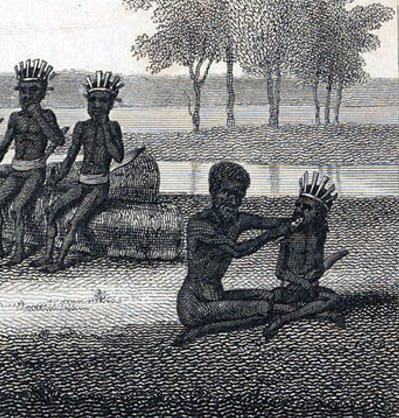

Prior [media]to the arrival of the British, the Aboriginal children who lived around Sydney Harbour spend their early years learning to hunt, fish and gather foods, and acquiring survival skills from their elders. Before initiation to adulthood, children accumulated knowledge, through a rich tradition of story-telling and song, of the complexity of their laws, religious beliefs and responsibilities to kin and their land. [9] Contact with the Europeans was to prove disastrous. Cultural interactions were violent, and competition for resources led to widespread starvation. Smallpox and other diseases were to decimate the Aboriginal people of Port Jackson, resulting in children dying or being left without adult care.

There were reports of numerous Aboriginal children in and around Sydney who were orphaned or destitute. Some were 'rescued' by settlers. [10] The [media]boy Nanbaree/Nanbarry was taken as a servant by the surgeon John White in 1789, and from his vantage point in the settlement was able to warn his people of punitive expeditions. [11] He later sailed on the Investigator with explorer Matthew Flinders, before returning to live in the bush. A 14-year-old girl Booron/Borrong (known to the settlers as Abaroo) lived with the family of Reverend Richard Johnson. She learnt English and wore European clothes, but returned to her people once the opportunity arose. [12] Other Aboriginal children entered settler households in Sydney as a valued source of labour; some were abducted on the expanding frontier for this purpose. Aboriginal children's capacity to adapt to such condition was seen as an 'experiment' for the 'civilising' forces of colonisation. Indeed, across the next two centuries, it was common for Europeans to 'interpret the rebellion of Aboriginal children as manifestations of their savage nature'. [13]

Children in early colonial Sydney

During the first years of the penal colony, European children shared with adults the privations of their new environment, including the shortage of food. Young children were particularly susceptible to sickness and accidents. The first recorded incident of a child 'lost in the bush' occurred in 1803, when the young son of a labourer collecting timber along Sydney Harbour wandered away. He was found exhausted and 'moaning' eight kilometres away. [14]

Although the numbers of convict and free-born children were to increase substantially in Sydney's first decades, they were a much smaller proportion of the overall population than in Britain. In the first New South Wales census delivered in 1828, children under 12 years comprised only 16 per cent of the total European population. It was not until the second half of the nineteenth century that the proportion of children in the population of the Australian colonies reached 40 per cent, a figure comparable with that of Britain.

Their relative scarcity in the context of a regulated penal colony meant that children's physical growth and behavioural characteristics were closely monitored. British colonisation of Australia occurred at a time of rising interest in children and philosophical debate about children's rights. The romantic conception that childhood was a state of innocence was popularised by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and others. This was at odds with the increasingly harsh realities for the children of the poor in Britain, who were victims of widespread rural distress and urban industrialisation. From the late eighteenth century, British practices of civic paternalism were increasingly separating poor children from their parents, and placing them in institutions. In New South Wales, the colonial administration and charities followed these British models of intervention in the lives of poor children and families with particular zeal. [15]

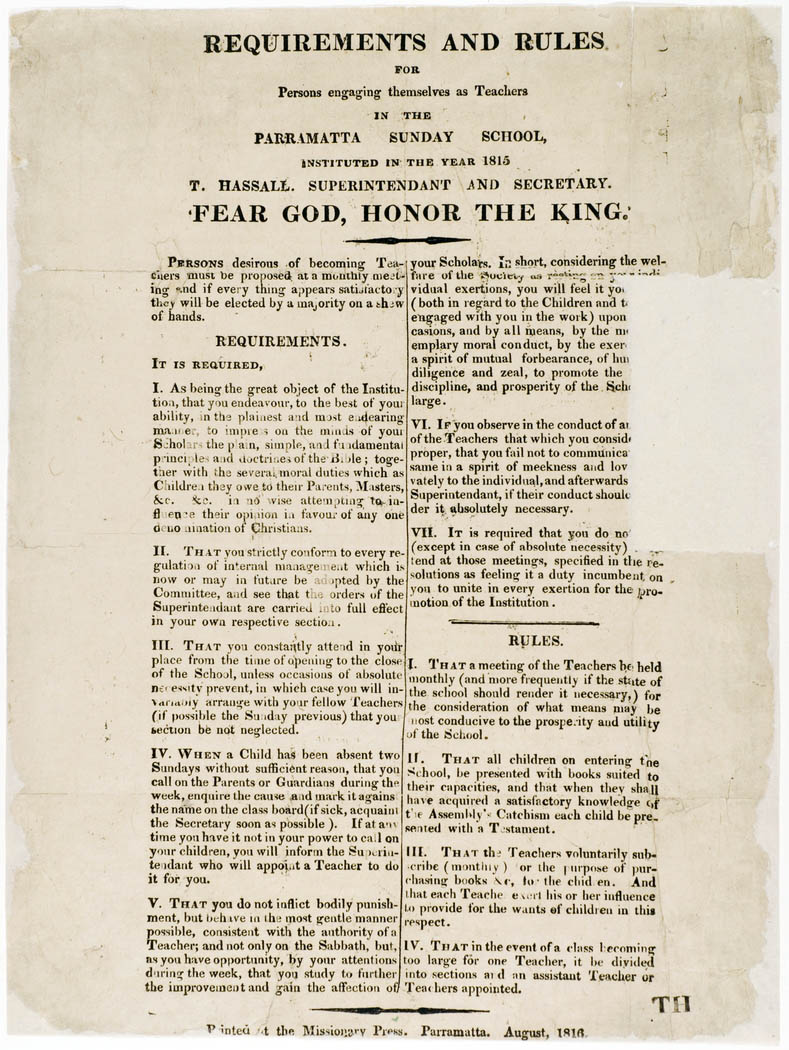

Under British [media]law, children as young as seven years could be criminally charged if it was ascertained they understood the difference between right and wrong. [16] About 15 per cent of all convicts sent to Australia were under 18 years, and some were as young as nine years. As more juveniles were transported from the 1820s, new attitudes about the reformation of child convicts led to their accommodation away from the 'contamination' of adults. By 1819, a juvenile section at Carters' Barracks at Brickfield Hill provided for the moral re-education of convict boys through religious instruction, industrial training and corporal punishment. [media]Girl convicts were incarcerated in the infamous Parramatta Female Factory, as were the infants and small children of convict women. White girls who were destitute in the rough environs of the penal colony were seen as particularly vulnerable because of their sexuality, and therefore in need of protection. Mrs King, wife of the Governor, played a key role in the establishment in 1801 of the first orphanage for girls, although it was not until 1818 that a similar institution was opened for boys. [17] Under Governor Macquarie, some Aboriginal children were offered 'protection' through incarceration in the short-lived Native Institution from 1814, initially located at Parramatta and from 1823 at Black Town. Not surprisingly, Aboriginal parents were unhappy with this arrangement, and withdrew their children. [18]

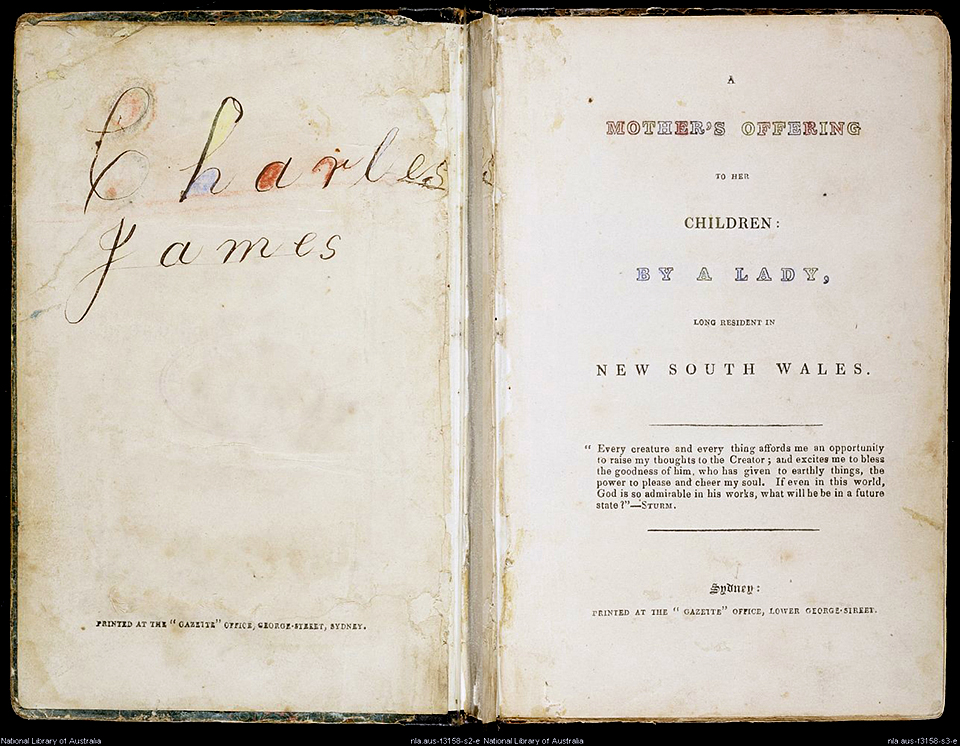

The lives of all children in early Sydney were determined by the expectations and realities of their class, gender and race. In 1802, Governor King commented that the white children of the settlement were either particularly 'fine' or particularly 'neglected'. [19] The children of the colonial elite were looked after by servants, and enjoyed a life of educational and leisurely pursuits typical of their class in Britain. The first children's book published in Australia, A Mother's Offering to Her Children, [media]for instance, instructed colonial children on the importance of appreciating nature and obeying parents. [20] Respectability and class position were maintained. Middle- and upper-class children were taught by tutors and governesses, or sent back to England for schooling. By the 1820s there were sufficient private schools in Sydney for this practice to be less common.

At this time, there was a generation of European children in Sydney who were 'native-born'. These 'currency' lads and lasses were referred to as 'cornstalks' as they were taller than their British counterparts. They also had a distinct way of talking. When reporting on the condition of the colony, Commissioner John Thomas Bigge found the children of convicts generally industrious and remarkably free of any criminal stain. This was seen as evidence of the success of the penal system.

Education, work and play

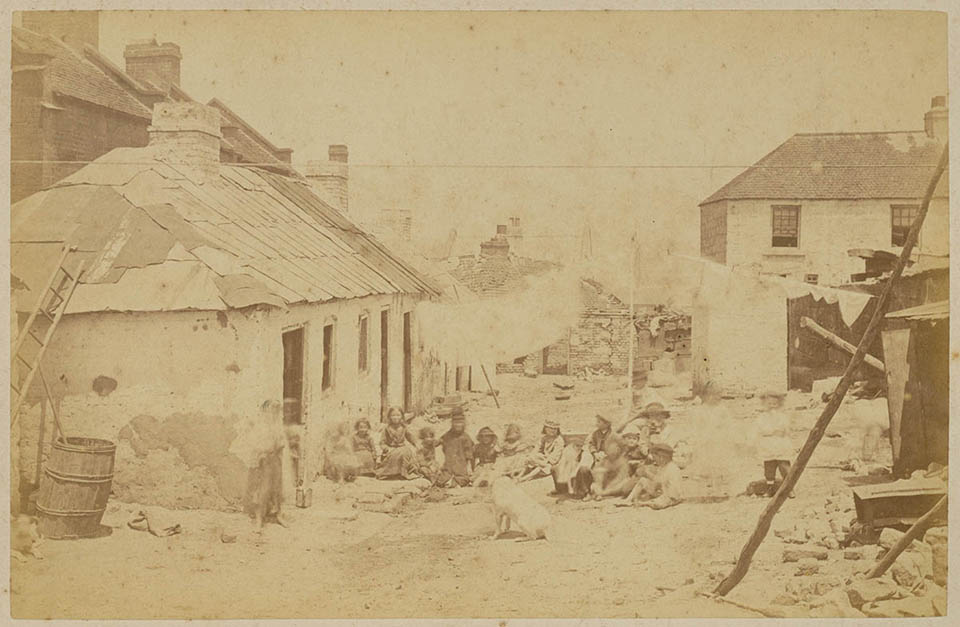

[media]The family immigration of free settlers in the 1830s and 1840s brought an influx of children into colonial New South Wales. The discovery of gold attracted more immigrants, and also resulted in many men leaving wives and children in the city while they travelled to the goldfields. Jan Kociumbas notes that in 1861 almost half of Sydney's population were children aged less than 12 years. Many lived in impoverished conditions in sole-parent families. [media]The high incidence of fathers working away from home for long periods, or deserting their wives and children altogether, was to continue throughout the nineteenth century. [21]

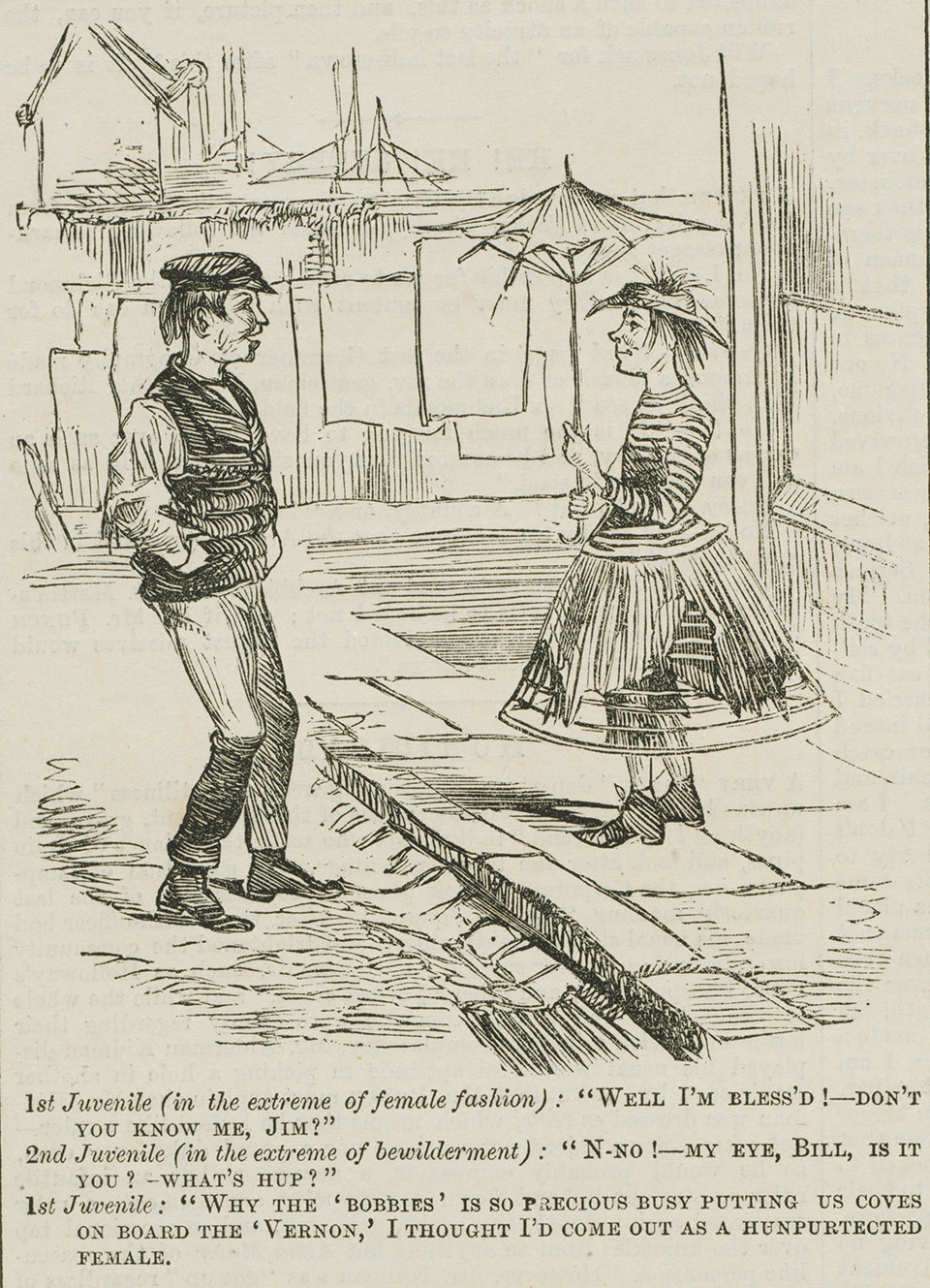

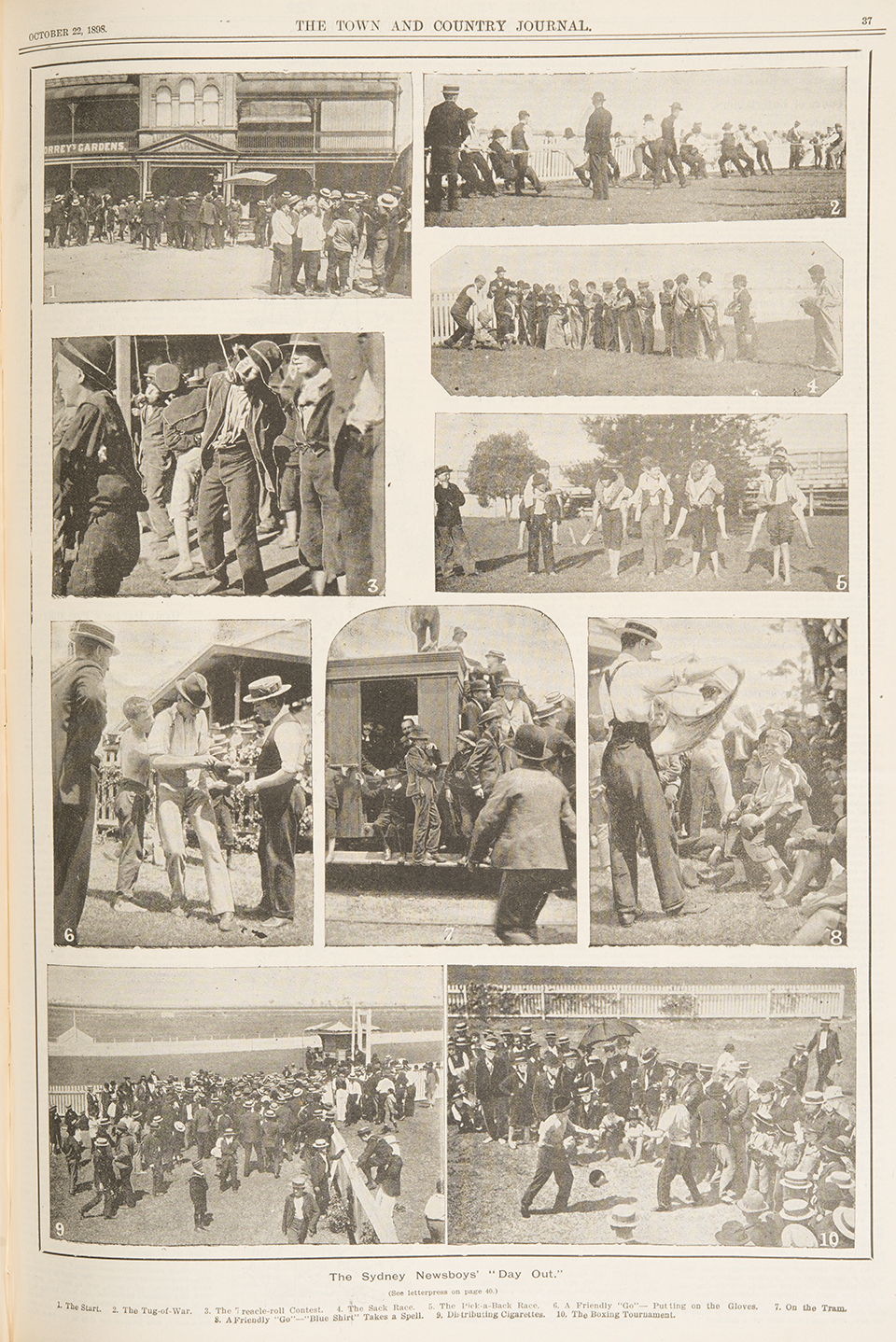

The [media]colonial government viewed the failure of parental control as a cause of increasing juvenile crime, demonstrated by the presence of 'ruffians' on Sydney's streets. A new wave of state control was directed at the children of the poor. [22] In 1857 legislation gave the Destitute Children's Society power to detain young people, up to 19 years old, in residential institutions. The Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children opened in 1858, and by the 1880s accommodated around 800 'neglected' or orphaned children in a self-sufficient barracks system. The Biloela Industrial School for Girls was established at the old convict barracks on Cockatoo Island, to be relocated in 1887 as the Parramatta Industrial School for Female Children. [23] Boys from as young as three years were placed in nautical reformatories for military-style training, on the boats Vernon and Sobraon docked at Cockatoo Island. Children in institutional care generally experienced hardship, fear and abuse, and they sporadically rioted in protest over their conditions. Gradual reforms of the system led to the boarding-out of many children to be trained in private homes.

As the nineteenth [media]century progressed, social attitudes in the Australian colonies were more markedly sentimental towards children, and elevated the status of mothering and domesticity of the home. Expectations about child development were gendered, with the idealisation of the 'motherly' girl and the 'manly' boy illustrating the importance given to such grown-up qualities. While adult discipline was believed necessary, Sydney's middle-class children were often seen to be indulged by their parents and to enjoy greater freedoms than children in Britain. Ethel Turner's classic novel, Seven Little Australians (1894), offers an insight into the experiences of middle-class childhood [media]in Sydney through the story of the mischievous Woolcot children. [24]

[media]For poorer families, children's labour remained crucial for the family economy. Children worked in family businesses, and girls undertook a range of domestic and child-minding chores. On the streets of Sydney, children ran the messages, and sold matches, flowers and other everyday items. When his father's illness plunged his family into poverty in the early 1880s, for instance, Jack Lang (who was to be a controversial Labor premier of New South Wales 1925–7, 1930–32) began working at the age of seven. He peddled newspapers and vegetables from a billycart around Surry Hills, often until midnight. [25] Food processing, textile and other factories employed child and juvenile workers, and in particular offered girls an alternative to domestic service. However, children's labour outside the home was increasing regulated through government legislation. By 1896, the New South Wales Factories and Shops Act restricted the working hours of children in order to encourage school attendance.

There had been limited government assistance for schools for poorer children from the early years of the penal colony, primarily through grants to the Anglican Church. Private day and boarding schools were well established by the mid-nineteenth century for the children of the middle class. However, a Select Committee in 1844 found that half of all children in New South Wales did not attend school. In response, two state organisations were founded: the Board of National Education to support a public education system, and the Denomination School Board to provide state subsidies to church schools, mainly Catholic schools. The National School in Fort Street was opened in 1850 as a model of a government school.

In 1880 the Public Instruction Act enforced compulsory education from six to 14 years. [26] Although there were still reports of absenteeism, often due to the work or family responsibilities of older children, the experience of school became a common one for all of Sydney's children. Most children also attended Sunday school and church each week, and religion played an important role in their moral instruction and sense of family and community. For children growing up in Sydney's Irish Catholic neighbourhoods, the networks surrounding the parish church were particularly important in fostering identity.

[media]As leisure time and facilities expanded, children also participated in attractions that marked Sydney's growing prominence within the British Empire. For instance, almost 28,000 visitors (many of them children) flocked to the Sydney International Exhibition on Foundation Day, 26 January 1880. They enthusiastically cheered a children's choir of 1,000 members singing temperance and imperial songs, including 'Rule Britannia' and 'Advance Australia Fair'. [27] Middle-class children enjoyed family outings, picnics by the harbour and played organised sports, such as tennis, through local clubs or church groups. For working-class children, the local streets were most often the site of play and social interaction, much to the concern of social reformers.

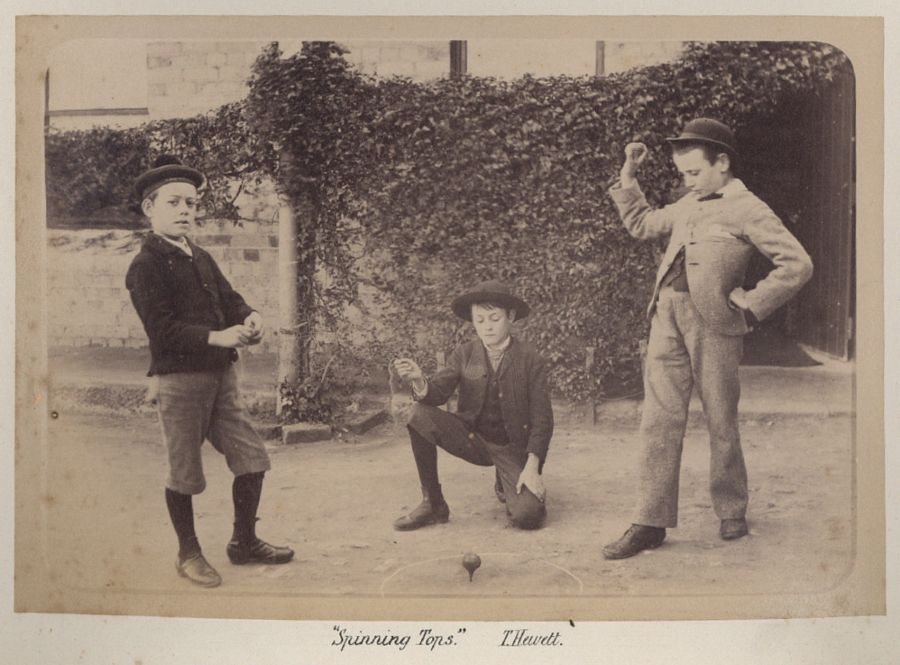

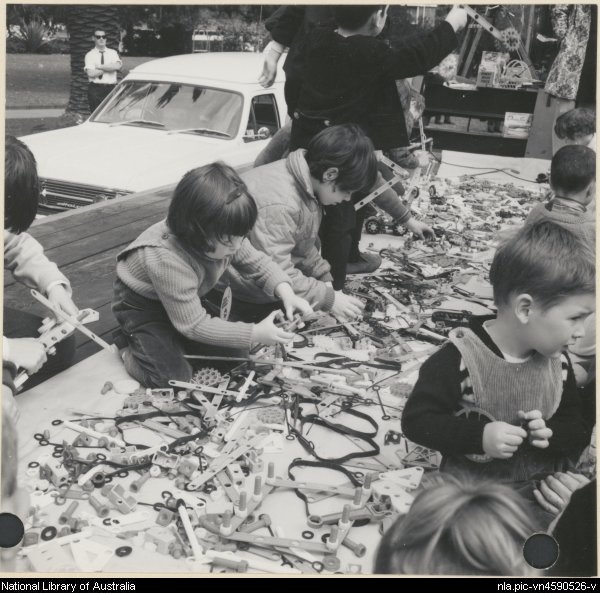

Children's books, magazine and [media]toys were becoming more varied and affordable, and children embraced an expanding culture of mass production and consumerism in their games and daily lives. In 1910, Dr Percival R Cole, Vice-Principal of the Sydney Teacher's College, surveyed 177 boys and 165 girls aged between nine and 13 years about the 'definite instinct' of children to collect objects for display and exchange. He found little difference between the sexes in the preferences of these Sydney children for collectibles such as cigarette cards, postcards, shells, marbles and stamps. [28]

Children in the new century

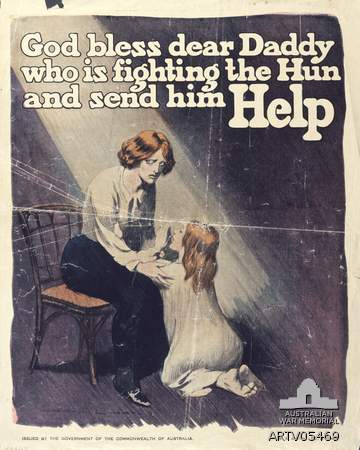

The [media]experiences of children in Sydney in the first decades of federated Australia were shaped by national and international events and by the rapid pace of technological change. Children experienced the impact of World War I within the context of family, as their fathers, brothers and other relatives enlisted in Australian Imperial Force. Recent historical scholarship has examined how families and communities in Australia mourned their dead, and has traced the long-term burdens placed on families by ex-servicemen who returned wounded, disabled and suffering from psychological trauma. [29]

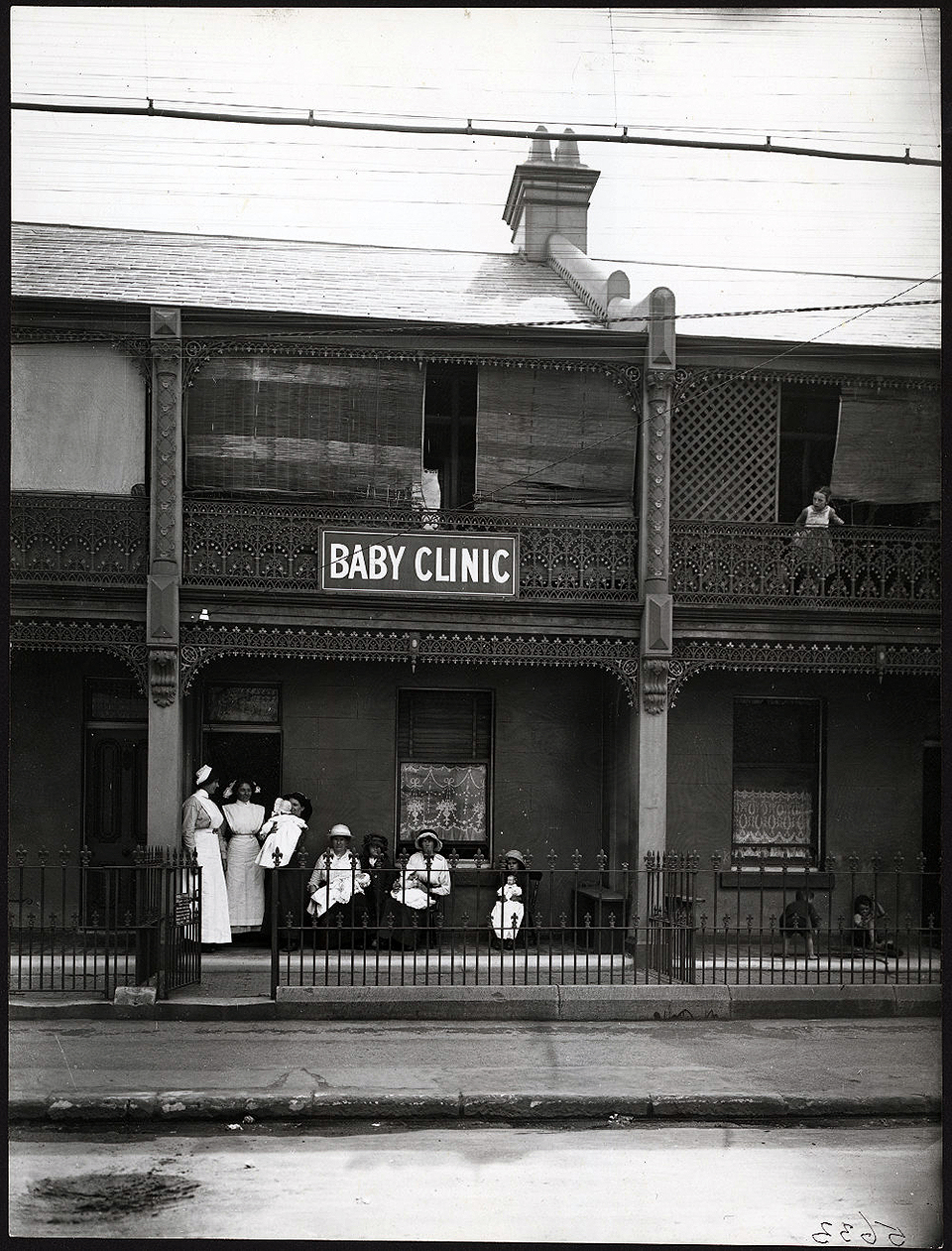

The [media]emotional and physical costs of World War I gave an added impetus to social expectations of improved and healthier living conditions. Family size was shrinking, down to an average number of five children by the early 1900s, despite a strong pro-natalist push from the government. Concerns about high infant mortality, especially in overcrowded inner suburbs, were addressed by the opening of Sydney's first Baby Health Centre in Alexandria in 1914. [30] By 1939 there were 57 centres in metropolitan Sydney. The Maternal and Baby Welfare Branch of the Department of Public Health provided medical supervision of pregnancy, childbirth, and the nurturing of infants and young children. Between the 1870s and 1930s, infant mortality in Sydney decreased by 75 per cent, although infant deaths remained significantly higher in the poorer, industrial suburbs. [31]

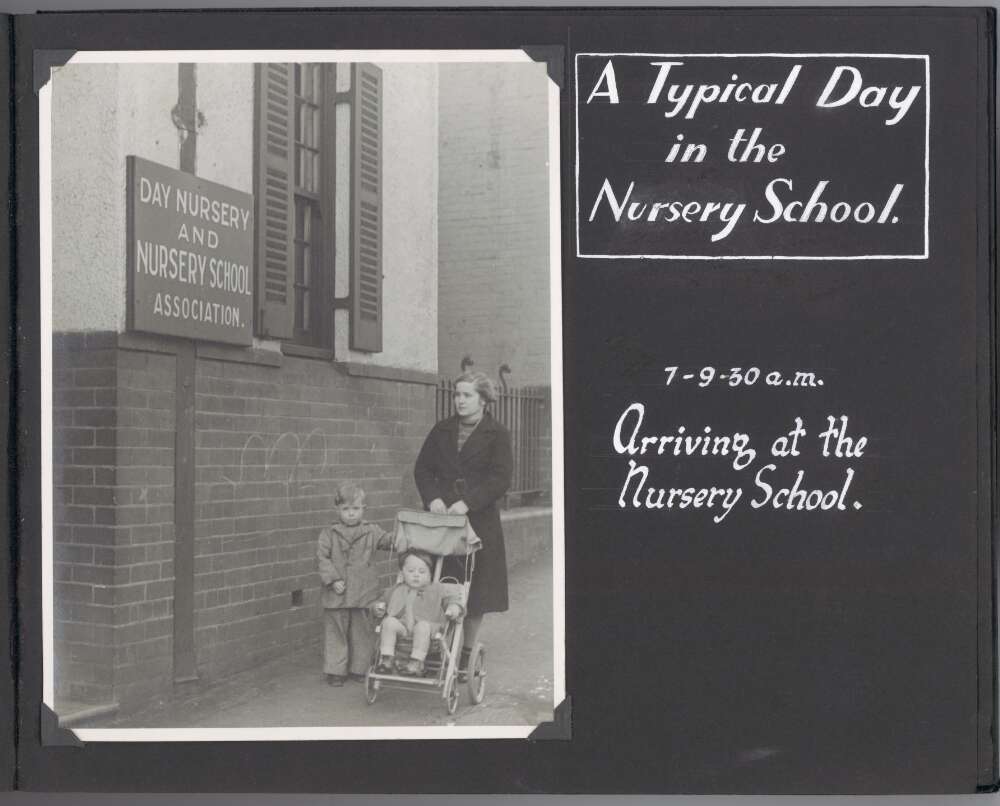

New attitudes towards motherhood stressed modern and 'scientific' practices in the organisation of the household and the care of children. Indeed, an emerging number of experts in child psychology and education in the interwar period ensured that child-rearing was linked to nation building. There was increasing interest in [media]early childhood education, and the number of kindergartens in Sydney proliferated, including those run by middle-class women for the small children of the poor. Government secondary schools grew and became more specialised. Assumptions based on gender and class channelled children aged 12 into academic, technical, and domestic science programs, setting the course for their future employment prospects. [32]

The 1920s were a decade of unprecedented suburban expansion in Sydney, as the population of the city reached one million. In 1911, over a third of Sydney's inhabitants lived in the inner suburbs, but this had fallen to just 16 per cent by 1933. [33] In contrast to the back lanes and overcrowding of older working-class Sydney, slum reformers and planning officials argued that the open spaces of the middle and outer suburbs provided a healthy environment where children could develop into responsible citizens. Physical activity was encouraged, and children were drilled at school in callisthenics, while competitive sport, especially for boys, started to expand.

Children [media]were also swept up in the popularity of surfing and swimming, and were among the millions of visitors flocking to beaches such as Bondi, Coogee and Cronulla. There was access to an increasing number of commercial amusements, from Taronga Park Zoo (on its present site from 1916) to Luna Park (opened in 1935). The annual Royal Easter Show, held at Moore Park, was attended by city families and had special activities for children. The Show was also the catalyst for many country children to visit Sydney with their families, and to explore the attractions of the city.

As historian Jill Julius Matthews has argued, Sydney dwellers in the early twentieth century were conscious of living in a modern world where technological change was accompanied by the promise of widening opportunities. The 'modern girl' (sometimes as young as the early teens) was the target of growing anxieties about the excesses of consumerism and sexualisation, as well as a symbol of the liberations of modern life. [34] Concurrent with such preoccupations, the world of childhood was increasingly represented as being distinct from that of adults. In the silent comedy film The Kid Stakes (1927), for instance, the inner-Sydney exploits of a children's gang led by irrepressible six-year-old Fatty Finn occur in a child-dominated space. [35]

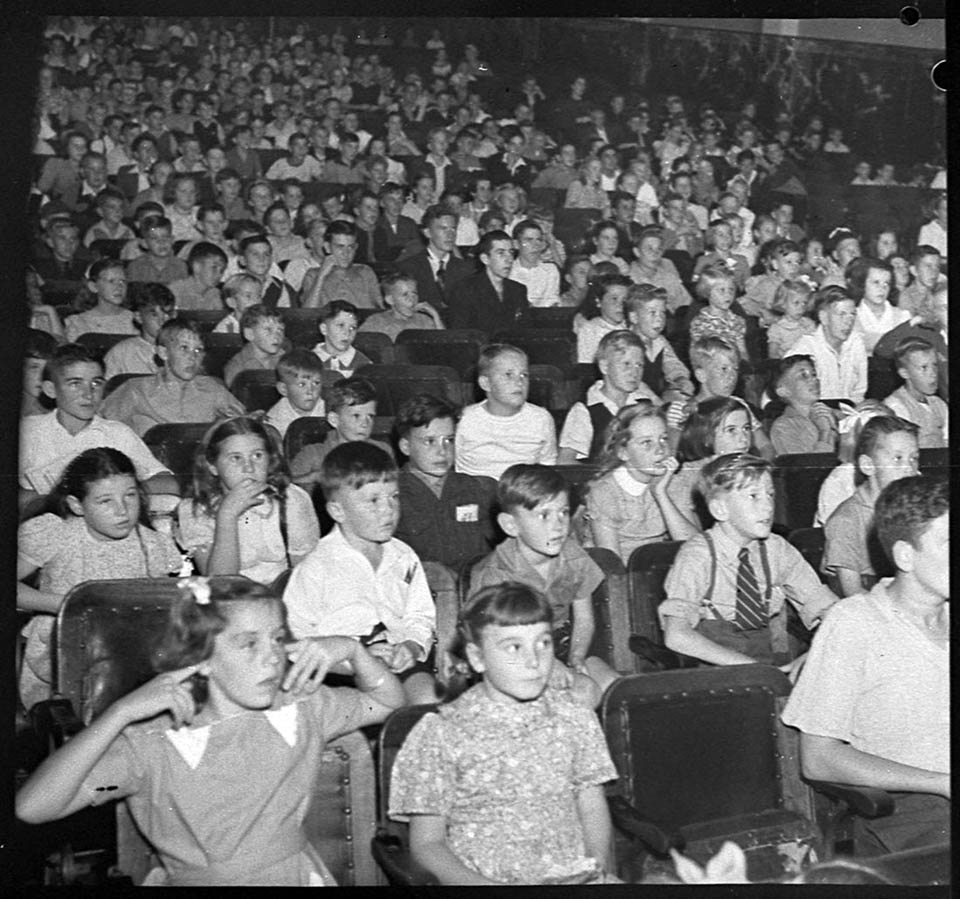

Radio widened the entertainment available to children in the home. But [media]it was the introduction of cinemas from the 1920s in Sydney's city centre and throughout the suburbs that was to radically transform leisure activities. Children were avid and regular attendees at the movies, and matinee sessions were intended to protect them from adult films. By 1951, a survey of 8,000 young people in Sydney found that at 13 years the most popular activity was playing sport, closely followed by going [media]to the cinema. [36]

Films provided [media]a welcome escape during the social upheaval and the economic distress of the 1930s. Experiences of children in Sydney during the depression were varied, and were determined by their class – and whether their parents were unemployed. The children of poor families were among those evicted by landlords for failure to pay rent, and could be found [media]in the unemployment camps like the one established near the La Perouse Aboriginal Mission at Botany Bay. [37] There was an increase in the number of children placed in institutional care as a result of family circumstances arising from the depression and World War II.

The comprehensive and sweeping extension of government control over all aspects of civilian life in World War II – including travel, consumerism, employment and entertainment – was to shape the experiences of children during wartime. Children were drawn into patriotic activities, assisting with air raid precautions or 'Victory' gardens. By early 1942, with the military front now in the Asia-Pacific region, some Sydney children were evacuated to the safety of the hinterland. Sydney's beaches were strewn with barbed wire, and parklands and schools were dug with slit trenches. There were shortages of foodstuffs and other goods, and an austerity lifestyle was promoted. Families were split apart as fathers joined the military forces, some for the whole six years' duration of the war. Mothers were actively recruited into essential war work, a situation that led to concerns from churches and social workers. Despite the anxieties and separation, many older children experienced wartime as an exciting period of change and expanding opportunities.

Children in postwar Sydney

In the years following the end of World War II, the national priority was to rebuild and support family and community life. The shortage of existing housing stock in Sydney, and the increase in population through the mass migration schemes of the 1950s–1970s, saw the rapid expansion of Sydney's suburbs. As the suburbs grew, so too did the distances between homes and places of work, entertainment and schooling. As cars became more affordable for Australian families, children were often the beneficiaries of the increased mobility they provided. Another significant trend in the postwar decades was the increasing participation of women, including those with children, in paid employment.

In 1954, when the young Queen Elizabeth commenced her triumphant Royal Tour at Sydney's Farm Cove in February, more than 1 million people – a large proportion being school children – gathered to welcome her. [38] But while the influences of Britain remained strong, the growing presence of US 'know-how', investment and popular culture in Australia was sometimes met with sweeping statements about the negative aspects of 'Americanisation' on young people. Popular culture was also seen to be corrupting the young. By 1952, Australians purchased 60 million comic books (most from the US) each year, and some educationalists and parents feared these could have an effect on the literacy of children. [39]

During her visit [media]to Australia in the mid-1950s to survey children's playlore, American folklorist Dorothy Howard recorded children's activities in the playgrounds of Sydney schools, including those in Erskineville and at the La Perouse Aboriginal Reserve. Across widely played traditional games such as skipping [media]and counting rhymes, hopscotch, string games and marbles, Howard found variations arising from gender, age, social class and cultural differences. [40] She noted that children's play was rapidly changing as suburban development encroached on open spaces, and also the increasing regulation of children's time as a result of extra-curricular activities, especially organised sports. [41] And the introduction of television in 1956, rapidly taken into Sydney's homes, was to irrevocably change children's culture and leisure.

The postwar period also saw the rise of a distinctive teen culture with its own magazines, fashion and music, and the teenager was seen as a necessary stage in the production of adulthood. Adolescence was to spawn its own subcultures, from the bodgies and widgies [media]of the late 1950s, the surfing cultures that continue to be particularly dominant in Sydney's beach suburbs, and the more recent formations of gangs, some proclaiming an ethnic identification. [42] Childhood has also increasingly been seen as a period of vulnerability amid the quickening pace of modern life. A sensational crime case in 1960 signalled such change when eight-year-old Graeme Thorne, whose father had won £100,000 in the Sydney Opera House lottery, was kidnapped for ransom, and murdered. The case attracted national media interest, with forensic evidence leading to the arrest and conviction of Thorne's killer, and was to heighten awareness of 'stranger danger'. [43]

Most significantly, the experiences of children in the late twentieth century were influenced by changes in family formation, with rising divorce rates and an increasing number of children living in sole-parent families. The first service of its kind, Elsie Women's Refuge in inner city Glebe was opened in 1973 to provide a haven for women and children escaping domestic violence. The Family Law Act of 1975 aimed to provide some protection to the economic circumstances of the children of separated parents. In the same year, the Henderson Report on poverty found that half of all children living in sole-parent households were economically disadvantaged. [44] In 1987, Prime Minister Bob Hawke made the famous statement that by 1990, no Australian child would live in poverty – a promise that was to prove impossible to keep.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Aboriginal people, including children, displaced from the New South Wales south coast, moved to the La Perouse Mission at Botany Bay. Redfern became a focus for the Aboriginal community and political activism. Autobiographical accounts by writers such as Ruby Langford Ginibi provide insight into the lives of Aboriginal children and families in Sydney during the late twentieth century. [45] In 1992, Prime Minister Paul Keating launched the International Year of Indigenous Peoples in Redfern. His speech[media] acknowledged that British colonisation had caused the dispossession of Aboriginal people, including through the government policy of removing Aboriginal children from their parents. The Bringing Them Home report into the impact of child separation on the lives of Aboriginal people was published in 1997, highlighting the childhood and family experiences of many Indigenous people living in Sydney. [46] In 2010 Indigenous children in New South Wales continue to be institutionalised at a higher rate than non-Indigenous children.

More than 75 per cent of Sydney's [media]growth between 1947 and 1971 came from migrants and their children, and since the 1980s Sydney has attracted more migrants than any other Australian city. [47] This has meant that Sydney's neighbourhoods and schools have become more culturally diverse, with some suburbs of ethnic concentration. The children of first- and second-generation migrants have often had to learn to bridge cultures and languages, and in some cases have experienced forms of ethnic discrimination from other children and adults. [48] The adaptability (or not) of migrant children to their new environment has continued to be seen as a measure of the success of migrant settlement and multiculturalism.

Children's schooling [media]was changing by the 1970s, as more liberal educational approaches to learning were introduced into Sydney's primary schools. There have been successive waves of educational reform, and increased parental involvement in the running of primary schools. In response to the needs of working parents (especially mothers) more preschool children in Sydney attend childcare centres than in the past, and a higher percentage of school-age children are in formal after-school care. The technological developments of recent decades have had an impact children's leisure activities, as electronic toys, music and video players as well as home computers are now commonplace.

In the 2006 census, children aged 0–14 years accounted for almost 20 per cent of Sydney's population. [49] Family size has declined, with one- or two-child families now the norm. Yet this trend has been accompanied by a higher profile for children overall, and the first decade of the twenty-first century has seen disproportionate growth in child-oriented services and entertainment. There has also been much public debate about such issues as childhood obesity and health, restrictions on children's play, educational curriculum and the sexualisation of children in the media. In May 2008, a Sydney exhibition by the internationally acclaimed photographer Bill Henson was controversially cancelled, following complaints that some images of naked children were 'pornographic'. [50]

Australian society is arguably more child-focussed now than at any other time in settler history, and attitudes towards children remain a gauge of broader social and moral concerns. While the culture of Sydney's children is increasingly global in its popular references and consumer practices, a recent study shows how children's daily experiences of play are also firmly linked to their immediate and localised circumstances of place and family. [51]

References

Alan Barcan, Two Centuries of Education in New South Wales, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1988

Paul Cliff (ed), The Endless Playground: celebrating Australian childhood, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2000

Kate Darian-Smith and June Factor (eds), Child's Play: Dorothy Howard and the Folklore of Australian Children, Museum Victoria, Melbourne, 2005

Dorothy Scott and Shurlee Swain, Confronting Cruelty: Historical Perspectives on Child Abuse, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2002

Gwyn Dow and June Factor (eds), Australian Childhood: An Anthology, McPhee Gribble, Melbourne, 1991

June Factor, Captain Cook Chased a Chook: Children's Folklore in Australia, Penguin, Melbourne, 1988

Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009

Jan Kociumbas, Australian Childhood: A History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1997

Kathryn Marsh, The Musical Playground: Global Tradition and Change in Children's Songs and Games, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008

Jill Julius Matthews, Dance Halls and Picture Palace: Sydney's Romance with Modernity, Currency Press, Sydney, 2005

John Ramsland, Children of the Back Lanes: Destitute and Neglected Children in Colonial New South Wales, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1986

Henry Reynolds, With the White People: The crucial role of Aborigines in the exploration and development of Australia, Penguin, Melbourne, 1990

Peter Spearritt, Sydney's Century: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2000

Notes

[1] Victor Daley, Bulletin, 26 February 1898, republished in Ian Turner, Cinderella Dressed in Yella, Heinemann Educational, Melbourne, 1969, pp 121–4

[2] 'J.A.P.', Bulletin, 12 March 1898; see June Factor, Captain Cook Chased a Chook: Children's Folklore in Australia, Penguin, Melbourne, 1988, pp 119

[3] John Peat, Bulletin, 9 April 1898; see June Factor, Captain Cook Chased a Chook: Children's Folklore in Australia, Penguin, Melbourne, 1988, pp 119–20

[4] Kate Darian-Smith, 'Images of Empire: Gender and Nationhood in Australia at the Time of Federation', in Kate Darian-Smith, Patricia Grimshaw and Stuart Macintyre (eds), Britishness Abroad: Transnational Movements and Imperial Cultures, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2007, pp 157–9. For the 'Little Boy from Manly', see Richard White, Inventing Australia 1688–1980, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1981, pp 110–24; Robert Crawford, 'A Slow Coming of Age: Advertising and the Little Boy from Manly in the Twentieth Century', Journal of Australian Studies, vol 67, 2001, pp 126–43

[5] Histories of children that explore New South Wales and Sydney include Gwyn Dow and June Factor (eds), Australian Childhood: An Anthology, McPhee Gribble, Melbourne, 1991; Jan Kociumbas, Australian Childhood: A History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1997; Dorothy Scott and Shurlee Swain, Confronting Cruelty: Historical Perspectives on Child Abuse, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2002

[6] Much census and other classification data take 14 as the upper age for children over this period

[7] Robert Holden, 'First Children: Pre-colonial – and colonial to c1849', in Paul Cliff (ed), The Endless Playground: celebrating Australian childhood, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2000, p 1; Robert Holden, Orphans of History: the Forgotten Children of the First Fleet, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2000

[8] Watkin Tench, 1788: Comprising 'A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany' and 'A Complete Account of the Settlement of New South Wales', Tim Flannery (ed), Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1996, p 41

[9] Jan Kociumbas, Australian Childhood: A History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1997, pp 2–5

[10] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2009, pp 499–503. Karskens also discusses the children Nanbarry, Boorung and others throughout her perceptive account of settler-Indigenous relations in early Sydney

[11] Jan Kociumbas, Australian Childhood: A History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1997, pp 1–2 10; see also Isobel, Nanbaree, Natural History Museum, London, 1995

[12] Jan Kociumbas, Australian Childhood: A History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1997, p 2

[13] Henry Reynolds, With the White People: The crucial role of Aborigines in the exploration and development of Australia, Penguin, Melbourne, 1990, p 186

[14] Kim Torney, Babes in the Bush: The Making of an Australian Image, Curtin University Books, Perth, 2005, pp 46–7

[15] Patricia Crawford, '"Civic Fathers" and Children: Continuities from England to the Australian Colonies', History Australia, vol 5, no 1, 2008, pp 04.1–16

[16] It was not until 1847 that British criminal law distinguished between children and adult offenders. Children under 14 years, however, could still be sent to prison until the 1908 Children's Act

[17] Jan Kociumbas, Australian Childhood: A History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1997, p 43

[18] Patricia Crawford, '"Civic Fathers" and Children: Continuities from England to the Australian Colonies', History Australia, vol 5, no 1, 2008, p 04.1

[19] Robert Holden, 'First Children: Pre-colonial – and colonial to c 1849', in P Cliff (ed), The Endless Playground: celebrating Australian childhood, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2000, p 1–2

[20] Attributed to Charlotte Barton, A Mother's Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales, Sydney Gazette Office, Sydney 1841

[21] The New South Wales censuses of 1891 and 1901 recorded that one married man in seven was living away from his family on the census night, compared to one in 15 married men in England and Wales. Jan Kociumbas, Australian Childhood: A History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1997, p 77

[22] For an overview see John Ramsland, Children of the Back Lanes: Destitute and Neglected Children in Colonial New South Wales, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1986

[23] This was to become the Parramatta Girls Home, officially closed in 1974. The site is now used as the Norma Parker Detention Centre for Women. See Parragirls website, http://www.parragirls.org.au, viewed 16 March 2010

[24] Ethel Turner, Seven Little Australians, Ward, Lock & Bowden, London, 1894

[25] Lang stated these experiences influenced him to introduce child endowment to New South Wales in 1927. His memoir is in Paul Cliff (ed), The Endless Playground: celebrating Australian childhood, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2000, pp 22–5

[26] For an overview of the New South Wales education system see New South Wales Department of Education and Training, Government Schools of New South Wales 1848–2003, Sydney, 2003, pp 6–13; see for more detail Alan Barcan, Two Centuries of Education in New South Wales, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1988

[27] Linda Young, 'Interested, Entertained and Instructed: Looking at the Exhibition', in Peter Proudfoot, Roslyn Maguire and Robert Freestone (eds), Colonial City, Global City: Sydney's International Exhibition 1879, Crossing Press, Darlinghurst, pp 114–5

[28] Percy R Cole, Sydney Mail, 20 July 1910, 19 October 1910; for a detailed discussion of the findings of the Cole survey, see June Factor, Captain Cook Chased a Chook: Children's Folklore in Australia, Penguin, Melbourne, 1988, pp 215–21, 224–31

[29] See, for instance, Tanja Luckins, The Gates of Memory: Australian people's experiences and memories of loss in the Great War, Curtin University Books, Fremantle, 2004; Marina Larsson, Shattered Anzacs: Living with the Scars of War, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2009

[30] From 1908, concerns about infant health led to home visits by nurses to new mothers in working-class suburbs such as Alexandria and Waterloo

[31] Peter Spearritt, Sydney's Century: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2000, p. 201

[32] By the mid-twentieth century, secondary schools became more comprehensive in their offerings and the school leaving age was raised to 15; see Alan Barcan, Two Centuries of Education in New South Wales, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 1988

[33] Peter Spearritt, Sydney's Century: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2000, p 33

[34] Jill Julius Matthews, Dance Halls and Picture Palace: Sydney's Romance with Modernity, Currency Press, Sydney, 2005

[35] The film The Kid Stakes (1927) was directed by Tal Ordell, based on the cartoon character Fatty Finn created by illustrator Syd Nicholls, and filmed in working-class Woolloomooloo and wealthier Potts Point

[36] By the age of 18 years, going to the cinema was recorded in the survey as the most popular leisure activity. Peter Spearritt, Sydney's Century: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2000, p 221

[37] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2005, pp 123–4

[38] See Peter Spearritt, 'Royal Progress: The Queen and her Australian Subjects', Australian Cultural History, no 5, 1986, pp 75–14; Jane Connors, 'The 1954 Royal Tour of Australia', Australian Historical Studies, vol 25, no 100, April 1993, pp 371–82

[39] Mark Finnane, 'Censorship and the Child: Explaining the Comics Campaign', Australian Historical Studies, vol 23, no 92, 1989, pp 220–40

[40] See index cards and notes in the Dorothy Howard Archive, Australian Children's Folklore Collection (ACFC), Museum Victoria. Howard's extensive research provides a foundation for contemporary research on play: see the Australian Research Council-funded project led by Kate Darian-Smith, 'Childhood, Tradition and Change: A national study of Australian children's playlore', 2007–10, http://www.australian.unimelb.edu.au/CTC/contact.html, viewed 16 March 2010

[41] See Kate Darian-Smith and June Factor (eds), Child's Play: Dorothy Howard and the Folklore of Australian Children, Museum Victoria, Melbourne, 2005 for critical essays and the republication of articles by Howard based on research in Australia conducted in 1954–55

[42] For bodgies and widgies see Jon Stratton, The Young Ones: Working Class Culture, Consumption and the Category of Youth, Black Swan Press, Perth, 1992; for a semi-autobiographical account of Sydney's suburban teen culture in the 1970s, see Gabrielle Carey and Kathy Lette, Puberty Blues, McPhee Gribble, Melbourne, 1979; and for an interesting discussion on recent perceptions of 'Lebanese gangs' see Jock Collins, Greg Noble, Scott Poynting and Paul Tabar, Kebabs, Kids, Cops and Crime: Youth Ethnicity and Crime, Pluto Press, Sydney, 2000

[43] For accounts of the Thorne case see Stephen Garton, 'Feed him to the sharks': the Graeme Thorne kidnapping', Australian Cultural History, no 12, 1993, pp 29–42; Noel Sanders, 'TV Family 1960: TV, Gambling and the Graeme Thorne Case', Australian Cultural History, no 12, 1993, pp 43–51

[44] Commission of Inquiry into Poverty and Ronald Henderson, Poverty in Australia: an outline of the first main report of the Commission, Australian Government Printing Service, Canberra, 1975

[45] Ruby Langford Ginibi, Don't Take Your Love to Town, Penguin, Ringwood, 1988

[46] Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Bringing Them Home: National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, HREOC, Sydney, 1997

[47] Peter Spearritt, Sydney's Century: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2000, p 87

[48] See for instance interview with Monica Attard in Paul Cliff (ed), The Endless Playground: celebrating Australian childhood, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2000, pp 190–1

[49] 2006 Census figures are: children aged 0–4 years: 270,814, 6.6 per cent of population; children aged 5–14 years, 534, 214, 13 per cent of population.

[50] Police subsequently withdrew charges after the images were granted a Parental Guidance (PG) rating by the Office of Film and Literature Classification; David Marr, The Henson Case, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2008

[51] Unpublished research and fieldwork into children's play undertaken by the Australian Research Council-funded project led by Kate Darian-Smith, 'Childhood, Tradition and Change: A national study of Australian children's playlore', 2007–10. See http://www.australian.unimelb.edu.au/CTC/contact.html, viewed 16 March 2010. Also see Kathryn Marsh, The Musical Playground: Global Tradition and Change in Children's Songs and Games, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008

.