The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Paddington

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Paddington

Paddington is [media]probably best known today for its streets of restored terrace houses, with their distinctive cast-iron balcony railings, sloping down in waves from the Oxford Street ridge to the harbour shores below.

The area where the suburb is located was originally inhabited by the Gadigal peoples of the Eora nation, and the development of the suburb was largely due to changes to transport availability along the ridge. Originally there was the Maroo, a path used by local Aboriginal people, and a road of some form was built by Governor Hunter along this track to the South Head as early as 1803. Under instruction from Governor Macquarie, it was upgraded in 1811 for strategic purposes, making it able to accommodate wheeled vehicles. [1] A stone obelisk at Robertson Park, Watsons Bay, marks the date of its completion. The Sydney Gazette, writing of the new road in May 1811, accurately foresaw that it would become a fashionable [media]drive. [2] A year later, the same source referred to the roadway as a 'beautiful avenue of recreation, either as a pleasant ride or promenade' which had been carved out of 'a wild and almost impenetrable scrub'. [3] The road was improved by Major Druitt in 1820. The South Head Road, as it was named, gave faster access to the signal station at South Head, and it also became the access road to some of Sydney's salubrious villas built by the colony's emerging plutocracy. [4] It was renamed the Old South Head Road after construction of a new road to the South Head (New South Head Road) along the Harbour foreshore was begun in 1831.

Early grants

The first land grant in the Paddington area, of 100 acres (40.4 hectares), was made to Robert Cooper, James Underwood, and Francis Ewen Forbes. It was first promised by Governor Brisbane on 4 November 1823, although it was not gazetted until 1831. But in 1824 Cooper, Underwood and Forbes had commenced work on the Sydney distillery, located at the eastern end of Glenmore Road between Old South Head Road and Rushcutters Bay. [5] Cooper built his mansion, Juniper Hall, on the South Head Road ridge, and Underwood built his house on Glenmore Road, between today's Soudan Lane and the former distillery. [6]

[media]The distillery partnership broke up shortly afterwards. Underwood bought out Forbes's share in 1824 for £6,200 and soon bought out Cooper, with whom he had quarrelled, for a further £1,600. By July 1824, the works, which included eight vats and a large granary, were ready for business. There was a court case between Robert Cooper and James Underwood in the late 1830s, over both Juniper Hall and the 100 acres. Cooper got to keep his house and the three acres on which it stood, while Underwood got the remaining 97 acres. [7]

Paddington emerges

The suburb's name came about when in October 1839 James Underwood subdivided 50 of his 97 acres. He called his subdivision the Paddington Estate after the London Borough of that name, and it covered the land from Oxford Street down to present day Paddington Street.

[media]Early developments in the area followed soon after the commencement in 1841 of construction of Victoria Barracks, located 'two miles distant from Hyde Park along the South Head Road', [8] and built to accommodate members of the New South Wales Corps formerly housed in the town of Sydney. The village of Paddington soon emerged, much of it around the cottages of the many artisans –stonemasons, quarrymen, carpenters and labourers – who were working on the construction of the Barracks, [9] along with the dwellings of the small community that grew up to supply goods and services to the military establishment. A group of some of these 'modest houses' from the mid nineteenth century has survived into the twenty-first century.

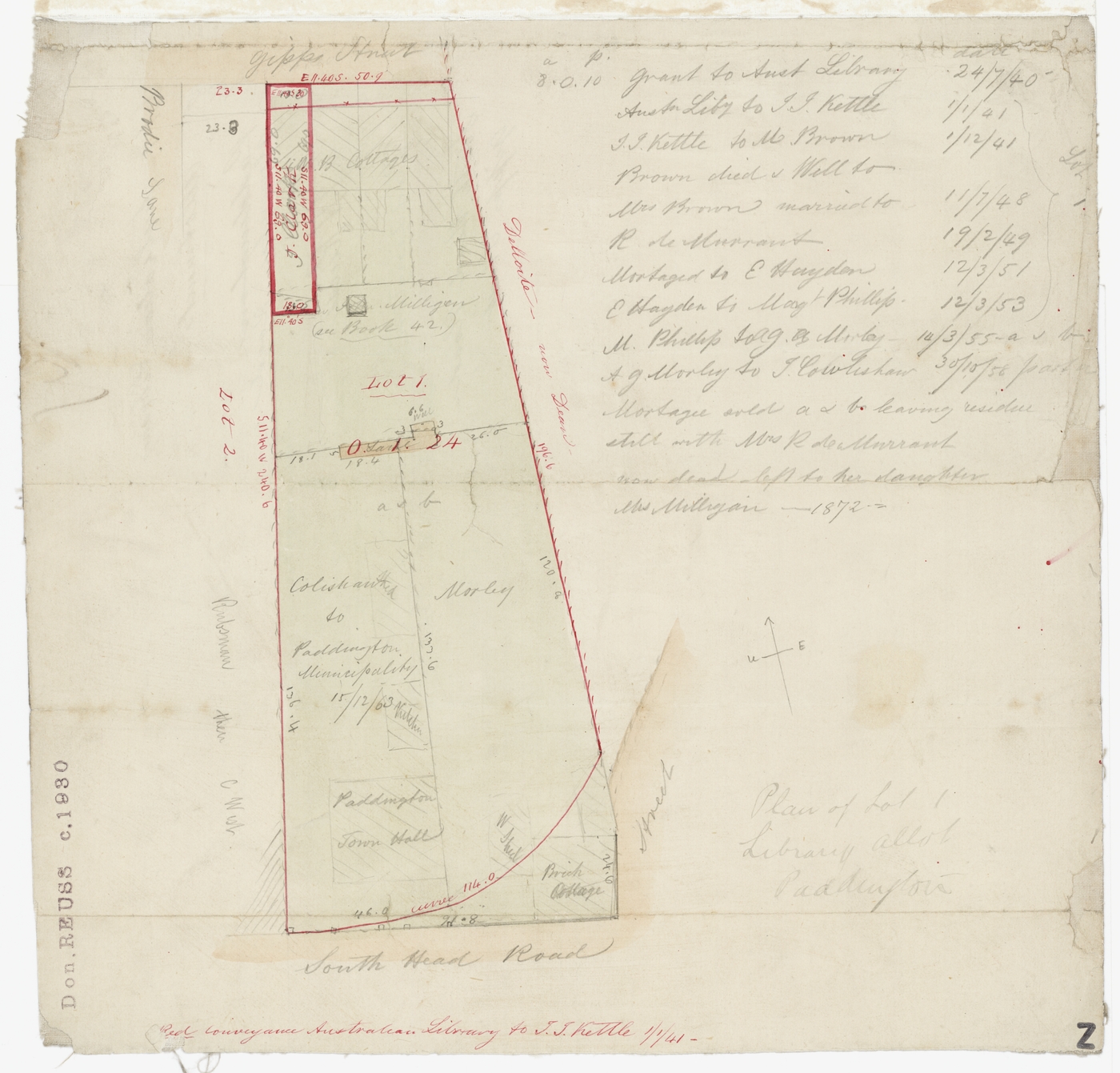

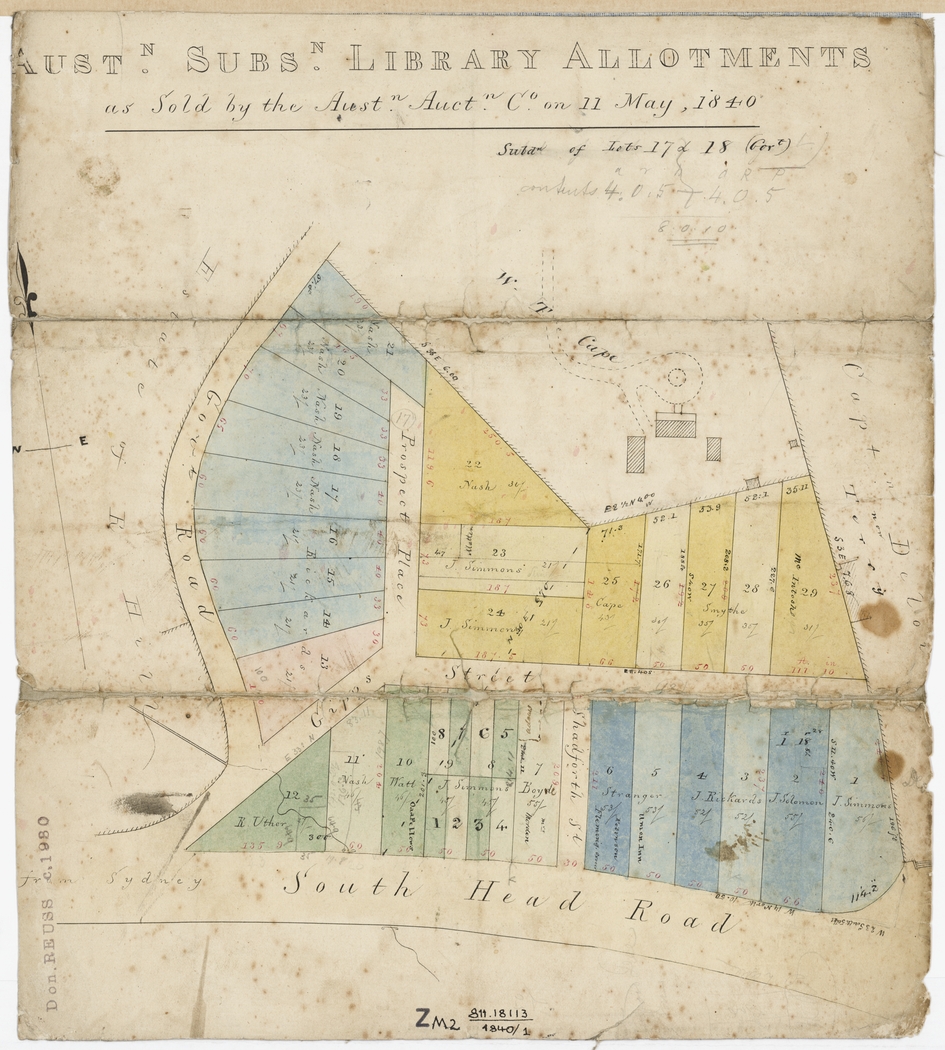

[media][media]The Australian Subscription Library, founded in 1826 by a group of Sydney 'gentlemen', was also the beneficiary of this relocation of the New South Wales Corps. Having been granted, in support of their project, a parcel of land opposite what was to become the barracks site, the syndicate subdivided its eight-acre holding and offered it at auction as The Australian Subscription Library Estate, the land realising an excellent return. [10] This May 1840 sale was a forerunner of the many subdivisions that would reshape the district by the end of the century; this sale released more land on the South Head Road, seen as a good business prospect to catch the passing trade en route to the Belle Vue Hill (later Bellevue Hill) and the South Head Lookout.

What emerged in the suburb was a clear class distinction; the working-class population, located largely on or near the South Head Road and involved in day-by-day activities in their trades – carpenters, stonemasons, builders, blacksmiths, plasterers, fencers, coachbuilders – either for locals or for the emerging gentry in the 'Rushcutters Valley'. These were a small group of 'gentlemen', professional men and merchants, many of whom built their imposing villas on the slopes leading down to the harbour. Apart from the mansions built earlier by Underwood and Cooper, these were joined by Elfred House, built in 1843 for WT Cape; Duxford House, built for Registrar of the Supreme Court John Gurner; Thomas Broughton's Bradley Hall, built in 1845; solicitor WG McCarthy's Deepdene House, standing in its acre of grounds; and Glen Ayr, built in the 1860s for Justice Sir Matthew Stephen. [11]

Water for the people

[media]The height of the ridge made it an ideal location for a reservoir, holding water for the surrounding lower-down suburbs. Work on the Paddington Reservoir commenced in 1864, although it was not completed until 1866. It was enlarged ten years later, to a holding capacity of 2 million gallons (9092 megalitres). [12] The reservoir operated until 1899, when the higher Centennial Park Reservoir was commissioned, after which the Paddington Reservoir was used by the Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage for storage, and from 1914 until 1934 it housed the Water Board's garage and workshop. Sold to Paddington Municipal Council in 1934, part of it was used as a service station, until the roof collapsed in 1990. Following major restoration and landscaping, it was reopened as Paddington Reservoir Gardens in 2009, [13] and is now a major tourist attraction.

[media]Such was Paddington's population growth and density that it was incorporated as a municipality in 1860, and by 1863 it could boast 535 dwelling houses there. The 'Victorian' suburb of Paddington grew into its present form largely during a 30-year boom that began in the mid-1870s, particularly with developments in public transport, initially with horse-drawn buses which travelled to the city and back from a terminus at Glenmore Road, and then with the introduction of steam trams, going through to Bondi in 1884. [14] All this facilitated the growth of a local 'high street' along the Old South Head Road, with the section between Boundary Street and Jersey Road being renamed as Oxford Street by the council in 1885, both to reflect its upgraded status and to bring it into line with the already renamed lower section from Hyde Park.

While the suburb's growth slowed during the economic depression of the 1890s, it was completed within the first decade of the twentieth century. The boom saw both the building of the Paddington Town Hall at a cost of £15,000 and its opening in 1891, and the break-up of many of the early nineteenth-century gentlemen's estates that had previously occupied the valley above Rushcutters Bay. Of the houses established by the Rushcutters Valley gentry, only the first to be built (Juniper Hall, built for gin distiller Robert Cooper in 1825) and the last (Olive Bank, built for John Ely Begg in 1869) survive today, as does the Town Hall, which remains a distinctive landmark, dominating the local skyline.

Landlords and lying-in

[media]Much of the building activity in late nineteenth-century Paddington was the work of 'spec' builders, who financed the construction of each new house from the sale of the last. The 'terrace' form of development typically found in Paddington suited this modus operandi, while also allowing economies of land use and building materials. The resulting housing was nearly always tenanted, and occupied, as entries in the Sands Sydney Directory show, by a peripatetic population. Conversely, as entries in the Paddington Council Rate Books indicate, landlords often held onto their investments for decades. [15]

Apart from new shops along the developing 'high street', there were other major changes in the streetscape of Paddington in the early years of the twentieth century. Reflecting an increasing concern for public health among elected officials and town planners, in 1901 the Benevolent Society purchased Flinton, a four-acre estate in Glenmore Road, for £14,000. [16] The original farmhouse consisted of 14 rooms on three levels with generous surrounding verandahs, and its new use was to be as a 'lying-in hospital' for women, with a bed-occupancy of up to 36 patients. The hospital commenced operations on 1 October 1901. Architect George Sydney Jones was then commissioned to design a new hospital wing, which was officially opened as the Royal Hospital for Women on 3 May 1905. The hospital remained at the site for almost 100 years, providing health care for thousands of women and their babies. In 1997 the hospital moved to new premises at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick, and the Paddington site was sold and developed for housing, becoming known as Paddington Green. [17]

Soon after the founding of the Royal Hospital for Women, a group of young women who were aware of 'the difficulties that beset the paths of working mothers' and interested in the care and education of young children, established the Sydney Day Nursery. The first such nursery was opened in Woolloomooloo, but in 1924 the group opened the Eastern Suburbs Day Nursery at 33 Heeley Street Paddington, in what had been Olive Bank. [18]

Migrants, students and gentrification

Also during the first half of the twentieth century, and reflecting this concern with healthy urban living, terraced housing in Australia fell into disfavour, and the inner-city areas where they were found often came to be considered 'slums'. Paddington, a mainly working-class area, was affected by this change in attitude. After World War II, at a time when the Anglo-Celtic Australian dream was for the quarter-acre block in the suburbs, and while Paddington still remained home to the many working-class families who had lived there for generations, it also became home to migrant workers and their families, who had no problems living in close proximity to their neighbours. These residents were joined from the early 1960s by hippies and students, attracted by the cheap rents.

The changing face of Paddington was also evident in other ways from those years. Gentrification also began in that decade, speeding up in the following years, and with it came an interest in the unique historical and aesthetic qualities of the area, and an awareness that the built environment of the suburb needed to be protected. As a result, a resident action group, the Paddington Society, was founded in 1964; it was probably the first resident action group formed in Australia. Its founding members were John Thompson as President, and Pat Thompson, with Don and Marea Gazzard, Viva Murphy and Sheila Rowan as committee members. [19] Today the suburb has a heritage listing, and its terrace housing is highly sought after and very expensive.

The entire suburb of Paddington, including the areas south of Oxford Street, was administered during the long boom of the late nineteenth century by the Municipal Council of Paddington, which was divided into two wards early in its history, with two further divisions occurring over time. But it was absorbed into the City of Sydney in 1948, and then divided between the City of Sydney Council and Woollahra Council in 1968.

Apart from its Victorian heritage, part of Paddington's charm today lies in two very different areas. It is home to some of Sydney's more prestigious art galleries, as well as having the well-known tourist attraction, the Paddington Markets on Saturdays, in the grounds surrounding Paddington Uniting Church and Paddington Public School.

References

Max Kelly, Paddock Full Of Houses: Paddington 1840-1890, Doak Press, Paddington, 1978

Clive Faro, Street Seen: a history of Oxford Street, Melbourne University Press, Carlton South, 2000

Notes

[1] See C Faro, Street Seen: A History of Oxford Street, MUP, Carlton South, 2000, pp 32-39

[2] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, May 1811

[3] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 8 August 1812

[4] See C Faro, Street Seen: A History of Oxford Street, MUP, Carlton South, 2000, pp 62, 68

[5] DR Hainsworth, 'Underwood, James (1771–1844)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/underwood-james-2751/text3895, viewed 17 October 2012

[6] DR Hainsworth, 'Underwood, James (1771–1844)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/underwood-james-2751/text3895, viewed 17 October 2012

[7] The Australian, 19 October 1839

[8] M Kelly, Paddock Full Of Houses: Paddington 1840–1890, p 16

[9] M Kelly, Paddock Full Of Houses: Paddington 1840–1890, p 19

[10] Australian Chronicle, 22 May 1840, p 2

[11] M Kelly, Paddock Full Of Houses: Paddington 1840–1890, pp 41–61

[12] 'Paddington Reservoir Gardens, Paddington', Sydney Parks History, City of Sydney website, http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/aboutsydney/HistoryAndArchives/SydneyHistory/ParksHistory/PaddingtonReservoirGardens.asp, viewed 16 March 2012

[13] 'Paddington Reservoir Gardens, Paddington', Sydney Parks History, City of Sydney website, http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/aboutsydney/HistoryAndArchives/SydneyHistory/ParksHistory/PaddingtonReservoirGardens.asp, viewed 16 March 2012

[14] David Keenan, The Eastern Lines of the Sydney Tramway System, Transit Press, Sydney, 1989

[15] M Kelly, Paddington: Paddock Full Of Houses: Paddington 1840–1890, pp 41–61

[16] 'History', Royal Hospital for Women Foundation website, http://www.rhwfoundation.com.au/aboutus/history.html, viewed 16 March 2012

[17] 'History', Royal Hospital for Women Foundation website, http://www.rhwfoundation.com.au/aboutus/history.html, viewed 16 March 2012

[18] 'Woollahra's suburbs in images – Paddington', Woollahra Council website, http://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/150/image_galleries/woollahras_suburbs_in_images/paddington, viewed 16 March 2012

[19] 'A brief history of The Paddington Society', Paddington Society website, http://www.paddingtonsociety.org.au/history.php, viewed 16 March 2012

.