The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Yarra Bay House

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Yarra Bay House

Yarra Bay House, [media]at 1 Elaroo Avenue, La Perouse, was a New South Wales Government institution for state children from around 1917 until the early 1980s. Like other homes run by the New South Wales Child Welfare Department, it is a site where the histories of Forgotten Australians and the Stolen Generations coalesce, not least because it was located next to the La Perouse Aboriginal Reserve. It has acquired special significance for Aboriginal communities since its deeds were given to the La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council in 1984. It is the administrative headquarters of the Land Council and a base for community organisation, services and activism.

Gooriwaal

Yarra Bay, on the northern head of Botany Bay, is a significant site of European colonisation. It was where Captain Arthur Phillip landed in 1788. [1] It was the last landfall of the doomed French explorer Lapérouse. It connected Sydney to the world, via the English Electric and Telegraph Company Cable Station, which was built in 1882 and is now the La Perouse Museum. As Maria Nugent has written, the area also served as the city's dumping ground. The Coast Hospital was established at Little Bay in 1881 after an outbreak of smallpox and became the major infectious diseases hospital for the city. [2] This sense of containment was amplified by the addition of the Botany Bay Cemetery and Long Bay Gaol. [3]

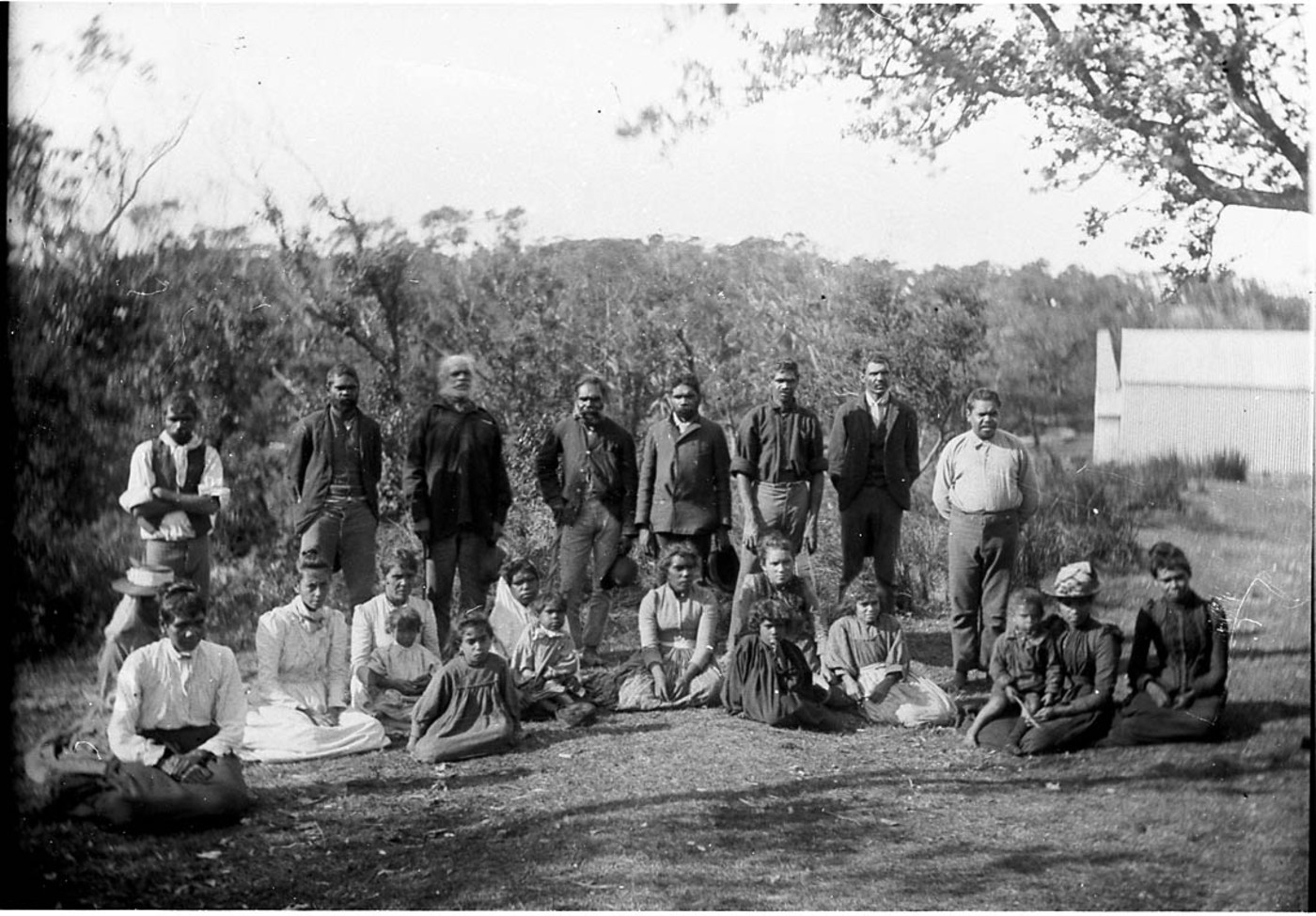

[media]In the 1880s the New South Wales Government and its newly formed Aborigines Protection Board were keen to remove Aboriginal people from Sydney's suburbs and wanted to wind-up the Aboriginal camps at Circular Quay, Neutral Bay, North Sydney, Watsons Bay and Botany Bay. At La Perouse, a group of mostly Tharawal people, linked with the Burragorang and Wollongong areas, occupied Crown land and lived by fishing, casual labour and selling baskets made by the women. Nugent says the area was a node in a coastal 'beat' and continually used by Aboriginal people. [4] They called it Currewol (Curriwal, Cooriwal), which is now spelled Koorewal, Guriwal or Gooriwaal. [5] This site, outside city limits yet within the government's orbit, was tolerable to the government. It became a quasi-institution for Aboriginal people. [6]

[media]The Aborigines Protection Board eventually allowed the Petersham Christian Endeavours, who were supported by George Ardill of the Petersham Congregational Church Fellowship, later the secretary of the Aborigines Protection Board, to erect a mission house, complete with a picket fence. [7] It was formally gazetted as an Aboriginal Reserve in 1895. [8] Botany Police persuaded the Protection Board to ring the settlement with barbed wire, and the missionary, Miss Retta Dixon, who would later found the Aborigines Inland Mission, was given a key to let fishermen out to sell their catch. [9] The La Perouse Mission was one of only a handful of Christian missions to Aboriginal people in New South Wales, and would last the longest.

Meanwhile, pleasure-seeking Sydneysiders were attracted to La Perouse by its beaches. In 1901 George Howe and William Rose opened the Yarra Bay Pleasure Grounds, complete with refreshment rooms, a cricket pitch and stables for 150 horses, at Yarra Beach. There were also refreshment rooms at the southern headland. [10] By 1910 the tramline had been extended and terminated at La Perouse on what is now known as The Loop. [11] La Perouse became famous for its sideshows, such as the snake man, and Aboriginal people became active participants in this economy, throwing boomerangs, selling spears and making shell art for visitors. Nugent says the expectation that one would see Aboriginal people at La Perouse was part of the attraction for tourists. [12]

The building of Yarra Bay House

It is not easy to provide an exact date for the construction of Yarra Bay House. The site where it stands was once part of a Public Recreation Reserve. According to Kate Blackmore and Paul Ashton, this reserve was subdivided in 1895 to create the La Perouse Aboriginal Reserve and in 1899 a six-acre (2.4-hectare) parcel was sold to the Eastern Extension Australasia and China Telegraph Co Ltd for a cable station. [13] Blackmore and Ashton state that the land remained undeveloped and in 1924 was sold as 'Cable Station Estate' to Henry Smith, a woolbroker from Melbourne, before being resumed by the government. They argue the house was built in 1928. [14]

[media]Other sources indicate Yarra Bay House was built as a second cable station, and dates from 1903, when the telegraph was transferred there. [15] The State Children's Relief Board's Annual Reports indicate it ran a home for boys at Yarra Bay from around 1917. [16] During the influenza epidemic of 1918 to 1919 Yarra Bay House was emptied to accommodate patients. [17] In June 1927 the Child Welfare Department announced it had bought 'the old cable station' at La Perouse, at a cost of £7,000, intending to convert it to a girls' industrial school to alleviate overcrowding at the Parramatta Industrial School. [18] By the following June about 50 girls were living at La Perouse. [19] Yarra Bay House was gazetted the following October. [20] It seems that, as was the case with Bidura and Royleston, the government had adapted an older building as a children's home. Ronald Arthur, who lived at Yarra Bay House as a ward of the state in 1940, certainly believed that the lovely building he remembers was old and had previously served as a cable station. [21]

La Perouse Training School

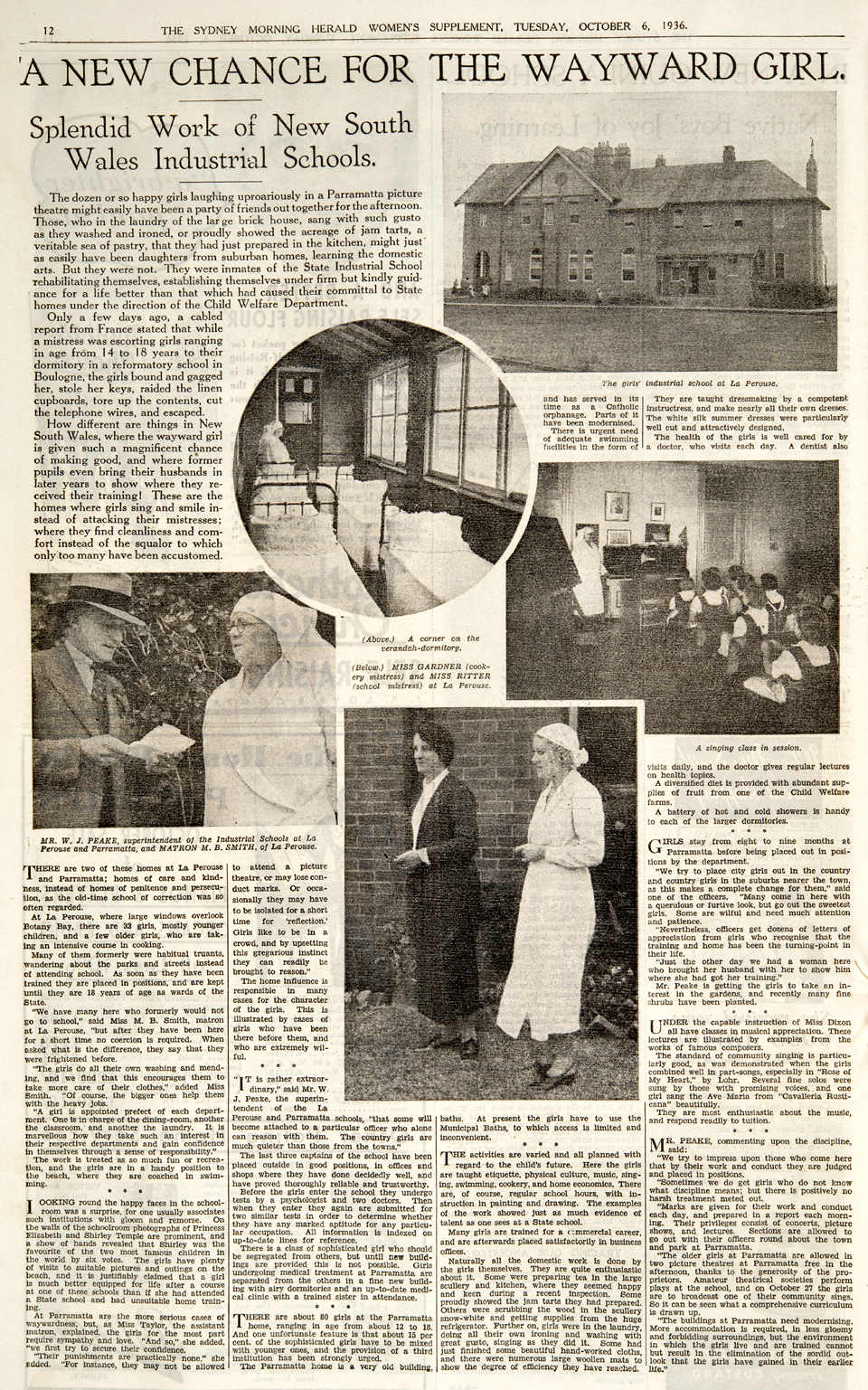

[media]The La Perouse Training School opened as an annexe of the Parramatta Girls' Training Home and was proclaimed on 28 July 1928 under the control of Parramatta's superintendent with a resident matron who was responsible for day-to-day operations. [22] The girls housed in La Perouse were considered to be 'less depraved and younger' than the other girls in Parramatta and were only placed there if it was justified by their 'general conduct and good health.' [23]

The discipline at La Perouse was more relaxed than in the main institution. The curriculum emphasised domestic duties but girls were allowed a degree of freedom to enjoy their beachside location. A former resident told author and Parragirls founder Bonney Djuric that La Perouse was for girls who did not 'muck up.' This resident recalled that a film, Lovers and Luggers, was shot close to the home, and included girls from the school in swimming scenes. This girl and a friend paid dearly for their freedom after they decided to walk into town one day and were picked up and raped. They said nothing about their ordeal. [24]

However, Stipendiary Magistrate JT McCulloch, who reviewed the Child Welfare Department in 1934, criticised the fact that the home was located in a holiday resort. [25] It was closed for that purpose in 1939. [26]

Yarra Bay Truant School

In 1939 the Child Welfare Department opened the building as a new institution, Yarra Bay House Truant School. Truancy, or the deliberate avoidance of school, was an offence under both the Public Instruction Act and the Child Welfare Act, and could result in a sentence of up to two years in what was referred to as a school for specific purposes, or special school. [27] Most children convicted of truancy were boys.

Although designated a truancy school, it is clear from oral history accounts that Yarra Bay received general welfare cases. Vincent Wenberg, who was interviewed by the Bringing them home oral history project, was one of a large family handed over to the Child Welfare Department by their father, after their Bundjalung mother left home in 1940 because of their father's violence. Vince and his brothers were sent to Yarra Bay House, and his sisters were sent to Bidura, while the family waited for a foster care placement. [28]

While young Vince was living at Yarra Bay he was fascinated by the workings of the Bunnerong Power Station:

I remember so many chimneys, this power station had…I knew it was one of the main sources of electricity for Sydney at the time. You used to see the boats coming in from Newcastle that brought coal in for the power station to burn…they used to call them 49ers in those days…The old Bunnerong Power Station…it got a bit smokey…I can't remember it smelling, maybe we were a bit far away for the smell we were right on the sea, with the sea breezes, it used to blow the smoke away. [29]

Vince also remembered the Department taking the boys on outings to Taronga Zoo and Manly, and seeing the submarine gates across Middle Harbour. [30]

Ronald Arthur grew up in foster care and lived about two years at Royleston before he was transferred to Yarra Bay:

I remember when they called me up to the office and they said 'oh you're going to be transferred to another home' and that's when they transferred me to Yarra Bay Boys' Home…Someone told me it was mainly for Aborigines but it wasn't, it was black and white. You know, that was the first time I ever saw a black man.

Ronald was taken to Yarra Bay by tram in 1940:

It was an old building, it was the old Cable Station from the First World War that was the first place Australia knew we were at war…I saw this big building, had the big wooden gates, big fence around, it had barbed wire around it too. It wasn't far from Long Bay Gaol. They used to fetch us stuff from Long Bay, bread and shoes. We had shoes there, we could wear shoes. It felt uncomfortable at first. We had shoes and socks…It was all right Yarra Bay, I've got a lot of mates there.

While there was no schooling at Yarra Bay, it was a much gentler place than Royleston, which Ronald thought was a prison, a 'punishment home', staffed by paedophiles. He thought Yarra Bay was good:

It was run different to Royleston, we didn't have to get down and scrub floors…the food was good, really good, they looked after us. There was only about 15 boys there…

We just had to make our bed and clean the floor and turns at washing up, which was understandable and that was it, then we'd go and play…one of the staff men would take us down for swimming, every day, which was very good [we'd] walk around the rocks, very good…we had a two-ounce pack of Western Tobacco…they encouraged you to smoke…we had a footy…it was very good.

Ronald spent nine months there, before going back to Royleston, from where he was, like most of the residents of Yarra Bay, sent to the Berry Training Farm. He never understood the reasoning behind any of his transfers. [31]

Yarra Bay Boys' Home

In the mid-1950s, the Child Welfare Department formally changed the name of the home to Yarra Bay Boys' Home. [32] By the 1960s it held 40 primary-school-age boys and had its own school. Child Welfare Department publications described the boys at Yarra Bay House as being 'dull' or 'educationally retarded', although it appears a severe shortage of foster placements was the main reason boys were detained. [33] In 1977, as the demand for residential facilities for children fell, the Department of Youth and Community Services thought Yarra Bay might be useful as a venue for 'special resocialisation programmes for intellectually handicapped people who are under the Minister's guardianship.' [34] Little appears to have happened and by the 1980s the house was empty.

La Perouse Aboriginal Land Council

When the Aborigines Welfare Board was abolished in 1969 the La Perouse community campaigned to remain on the La Perouse Reserve. They were successful and then waged another campaign for control of the land. By the 1980s, the Aboriginal community was making use of Yarra Bay House as a childcare centre and a base for the Aboriginal Medical Service. In 1984 the title to the land on which the settlement had stood, including the original portion alienated for Yarra Bay House and the building, was transferred to the La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council. [35] In 1988, when the community organised Survival Day as a protest against the reenactment of the arrival of the First Fleet and the bicentenary, Yarra Bay House was the hub of what became an Aboriginal [media]village. [36] [media]In 2014 the La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council is still based at Yarra Bay House, supporting its community. [37]

Further reading

Djuric, Bonney. Abandon All Hope: a history of Parramatta Industrial School. Georges Terrace: Chargan, 2011.

Find & Connect Web Resource Project for the Commonwealth of Australia. The Find & Connect web resource. 2011. www.findandconnect.gov.au.

Nugent, Maria. Botany Bay: where histories meet. Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2005.

Notes

[1] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2005), 1

[2] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2005), 38–45

[3] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2005), 58–59

[4] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2005), 54

[5] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2005), 53, 208–209n

[6] Naomi Parry, '"Such a longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880–1920', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales 2007, 160

[7] Naomi Parry, '"Such a Longing": Black and White Children in Welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880–1920', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales 2007, 160

[8] Naomi Parry, '"Such a Longing ": Black and White Children in Welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880–1920', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales 2007, 160

[9] Naomi Parry, '"Such a Longing ": Black and White Children in Welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880–1920', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales 2007, 160

[10] Kate Blackmore with Paul Ashton, 'Yarra Bay House Historical Study' (Sydney: New South Wales Heritage Council, 1985), 3

[11] 'Happy Valley, Chinese Market Gardens And Migrant Camps,' At the Beach: Convict, Migration and Settlement in South-East Sydney, Migration Heritage Centre, http://www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au/exhibition/atthebeach/happy-valley/, viewed 10 December 2014

[12] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet, (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2005), 71–73

[13] Kate Blackmore with Paul Ashton, 'Yarra Bay House Historical Study' (Sydney: New South Wales Heritage Council, 1985), 3

[14] Kate Blackmore with Paul Ashton, 'Yarra Bay House Historical Study' (Sydney: New South Wales Heritage Council, 1985), 3

[15] 'La Perouse Mission Church', NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, State Heritage Listings, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5061399, viewed 13 December 2014; Randwick Local Environment Plan, cited in 'Yarra Bay House,' NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, State Heritage Listings, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=2310236, viewed 13 December 2014; 'A Changing Landscape and a People Return,' At The Beach: Contact, Migration and Settlement in South East Sydney, NSW Migration Heritage Centre, 2011, http://www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au/exhibition/atthebeach/changing-landscape/, viewed 10 December 2014

[16] Naomi Parry, 'Yarra Bay House (1917–1923)', Find and Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01373b.htm, viewed 13 December 2014

[17] 'Influenza. Position Still Improving,' Sydney Morning Herald, 25 December 1918, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15817377, viewed 13 December 2014

[18] 'For Girls' School,' Evening News, 15 June 1927, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article121675769, viewed 13 Dec 2014; 'Delinquent Girls.' Sydney Morning Herald, 24 June 1927, 12, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16365074, viewed 13 December 2014

[19] 'Children Of The Abyss,' Sunday Times, 10 June 1928, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122803351, viewed 13 December 2014

[20] Kate Blackmore with Paul Ashton, 'Yarra Bay House Historical Study' (Sydney: New South Wales Heritage Council, 1985), 3–5

[21] Ronald Arthur interviewed by Jeannine Baker for the Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants oral history project, National Library of Australia, http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn5717091, viewed 13 December 2014

[22] 'La Perouse Training School for Girls (1928–1939)', Find and Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01072b.htm, viewed 10 December 2014. See also 'Newcastle Public Industrial School for Girls (1867–1871) / Biloela Public Industrial School for Girls (1871–1887) / Parramatta Industrial School for Females (1887–1912) / Girl's Training Home, Parramatta (1912–1975) / Kamballa (1975–1983)', in State Records Archives Investigator, Agency Detail 460, State Records NSW, http://investigator.records.nsw.gov.au/Entity.aspx?Path=%5CAgency%5C460, viewed 10 December 2014; Bonney Djuric, Abandon All Hope: a history of Parramatta Industrial School, (Georges Terrace: Chargan, 2011) 79–80

[23] La Perouse Training School for Girls (1928–1939), Find and Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01072b.htm, viewed 10 December 2014

[24] Bonney Djuric, Abandon All Hope: A history of Parramatta Girls Industrial School (Georges Terrace: Chargan, 2011) 78–80

[25] JE McCulloch, Child Welfare Department, Report on the General Organisation, Control and Administration of, with special reference to State Welfare Institutions, (Sydney: Government Printer, 1934) cited Naomi Parry, '"Such a Longing": black and white children in welfare in New South Wales and Tasmania, 1880-1920', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales 2007, 282

[26] Naomi Parry, 'La Perouse Training School for Girls (1928–1939)', Find and Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01072b.htm, viewed 10 December 2014

[27] Naomi Parry, 'Guildford Truant School for Boys (1917–1935)', Find and Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/nsw/NE01073, viewed 11 December 2014; Naomi Parry, 'Anglewood (1943–1994)', Find and Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE00403b.htm, viewed 11 December 2014

[28] Vince Wenberg interviewed by Frank Heimans in the Bringing them home oral history project, http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn2978303, viewed 11 December 2014

[29] Vince Wenberg interviewed by Ann-Mari Jordens in the Bringing Them Home after the Apology oral history project 2010, http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn4776744, viewed 10 December 2014

[30] Vince Wenberg interviewed by Ann-Mari Jordens in the Bringing Them Home after the Apology oral history project 2010, http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn4776744, viewed 10 December 2014

[31] Ronald Arthur interviewed by Jeannine Baker for the Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants oral history project, National Library of Australia, http://nla.gov.au/nla.oh-vn5717091, viewed 13 December 2014

[32] Donald McLean, Children In Need: An account of the administration and functions of the Child Welfare Department, New South Wales, Australia: with an examination of the principles involved in helping deprived and wayward children, (Sydney: Government Printer, 1955)

[33] Department of Youth and Community Services Annual Report 1977, cited in Naomi Parry, 'Yarra Bay Boys' Home (c.1955–1985)', Find and Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01375b.htm, viewed 10 December 2014

[34] Naomi Parry, 'Yarra Bay Boys' Home (c.1955–1985)', Find and Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01375b.htm, viewed 10 December 2014

[35] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2005), 171–181

[36] Maria Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet (Crows Nest: Allen and Unwin, 2005), 185–189, Heather Goodall, Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal Politics 1770–1972, (St Leonards: Allen and Unwin, 1996), 385

[37] La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council, Indigenous Directory, http://www.ourcommunity.com.au/directories/listing?id=59976, viewed 10 December 2014; Matt Thistlethwaite, Member for Kingsford Smith, Constituency statement, 'La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council', Hansard, House of Representatives, 13 February 2014, http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber%2Fhansardr%2F58a73839-3036-43f5-967d-8540f8c9a3db%2F0182%22, viewed 10 December 2014

.