The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Shaftesbury Reformatory

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Shaftesbury Reformatory

[media]The Shaftesbury Reformatory opened in 1880 on a site on New South Head Road, Vaucluse. Named after English social reformer Anthony Ashley-Cooper, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury [1], it served as a replacement for the Biloela Reformatory and Industrial School for Females and comprised a series of cottages and three solitary cells surrounded by high fences. The Reformatory usually housed up to 20 girls for one to five years. In 1904, the inmates of the reformatory were moved to Ormond House in Paddington and the site was subsequently used for a number of different purposes.

Establishment of the Reformatory

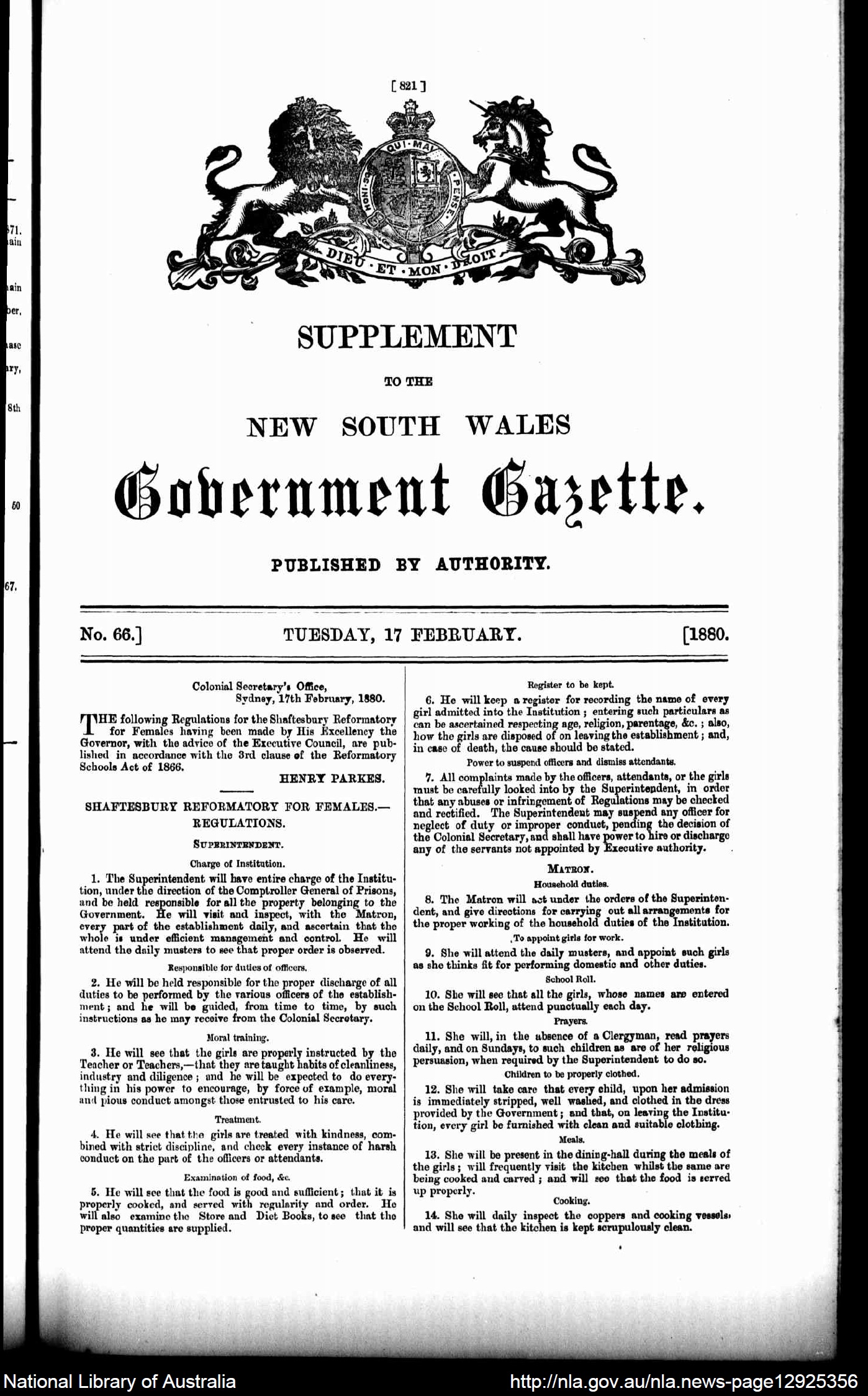

[media]The Reformatory Schools Act of 1866 deemed that any child under sixteen convicted of a criminal offence and sentenced to more than fourteen days imprisonment could be sent to a reformatory for one to five years instead of or in addition to time spent in goal.[2]

After several reports were made in the 1870s on the inadequacy of Biloela, the girls’ reformatory on Cockatoo Island, the NSW government needed to find an alternative location that wouldn’t have Biloela’s ‘dry, stony prison aspect’[3]. The site at Vaucluse was selected because it occupied ‘a position which, for a charming outlook on either hand and for healthfulness, could not be surpassed‘[4] .

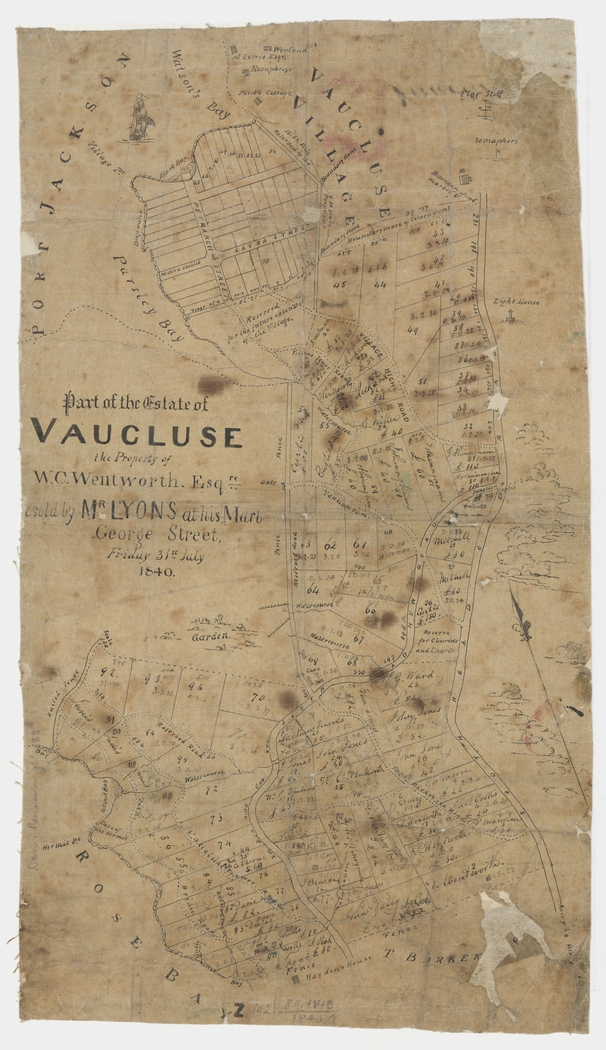

The land on which the Reformatory was built was part of a larger holding purchased for the purpose by the government from William Wallis in 1876[5]. The main Shaftesbury site, lying approximately between present-day Laguna Street and New South Head Road and Old South Head Road, measured some 7 acres (2.84 hectares).

The site had earlier formed part of the estate of William Wentworth, a crown grant of 370 acres (150 hectares) acquired in 1838 that was in addition to his original purchase of the 145 acre (58 hectare) Vaucluse estate in 1827. Much of the estate was subsequently subdivided and passed through the hands of several owners.

In 1853 when Surveyor General Thomas Mitchell completed a survey of the area, a hotel on the site[6] was recorded. “Just on the opposite side of the road to where the Vaucluse Bowling Green is today stood for many years a long, low verandahed building, built about 1850 as a hotel.”[7]

[media]In November 1877 the Colonial Architect’s office was advertising for tenders for the old hotel building to be repaired and altered as a reformatory for girls.[8] The works took some time, and although described as a ‘government reformatory’ in the Woollahra Municipal Council rate books in 1877[9] and the Female Reformatory, The Heights, Watsons Bay in The Sands Sydney Directory in 1879[10] , the property was only officially opened and proclaimed a reformatory for females in early 1880.[11] The Shaftesbury Reformatory School was controlled by the Comptroller General of Prisons until 10 April 1893, when it was run by the Charitable Institutions Department.[12]

Life in Shaftesbury Reformatory

[media]Biloela superintendent Mrs Agnes King was appointed as the superintendent and matron[13]of the new reformatory and she and twelve girls were moved from Cockatoo Island to Vaucluse in February 1880.

“..every part of the building have been designed in the most approved manner; and while throughout there is the unmistakable aspect of a place where the inmates are forcibly detained, there are many things about the style of construction and the fittings of the different compartments which give a more than ordinarily cheerful appearance to everything, and doubtless will have a very beneficial effect in the reformation of the girls. The ground in front of the building has been nicely laid out in grass plots and flower beds; and that part of the ground which is to be used by the inmates for recreation purposes has been enclosed by a galvanized iron fence, and is being turfed."[14]

As with many such institutions, life at the reformatory could be harsh.

‘Rioting occasionally took place, and the Institution was once set alight. The gentle Mrs King, the first matron, was replaced by another with more reputation for severity and discipline.

A younger and less troublesome type of inmate was found, as the Education Department took over the institution, and the little apple or hymnbook stealing child, escorted by a policeman, armed with a big warrant, did not require the same drastic treatment as the young lady from Cockatoo.

"I have found a great improvement since the first year I took over the institution," said the matron. "Where I used up thirty-six yards of cane a term, I can now easily manage with twelve.’[15]

Girls could be sentenced for a range of offences and for varying lengths of time: 14 year old Emily Miller was sentenced to 14 days in 1882 for stealing a diamond ring from her master[16]; Alice Bambilliski sentenced to two years in 1890 for stealing 25 pounds from the Kogarah Post Office[17]; and Annie Andrews, aged 15, was sentenced to two years and four months in 1897 for being an ‘idle and disorderly person’[18].

In 1892, more modifications to the original building took place:

‘The main building enclosed a central courtyard …three punishment cells with steel doors were added, together with a three metre corrugated iron perimeter fence, with the tops cut to a point to deter absconding. Accommodation for another forty-two inmates had also been provided, taking capacity to about seventy.’[19]

State Children Relief Board

There were 13 girls in residence in 1900 when the State Children's Relief Board took control of Shaftesbury. The Board then placed 25 female State wards (either invalids or girls who were unsuitable to apprentice as domestic servants) into the home in addition to the girls under sentence.[20]

In 1901 new legislation for reformatory schools was introduced, the Reformatory and Industrial Schools Act. The State Children's Relief Board took charge of the institutions for children and the management of Shaftesbury became the responsibility of the Superintendent at Parramatta. From that point, Shaftesbury held female state wards, as well as reformatory girls.

The Shaftesbury closed in March 1904 and the girls were boarded out. On 12 April 1904 the Shaftesbury officially ceased to be a reformatory school and by 1906 the site was being used as a depot for State Children, as an overflow from Ormond House in Paddington.[21]

Shaftesbury Institution

In 1908 the site became the Shaftesbury Institution for released prisoners and ‘the more hopeful cases among prisoners and inebriate females’.

The Shaftesbury Institution fell under the control of the Prisons Department[22], with a matron/superintendent in charge of its operations. During this time inmates received training prior to conditional release:

'The treatment is entirely different from that experience by prisoners in gaols, the object being to have the conditions as near as possible similar to those they would enjoy when engaged upon domestic duties outside. In other words, Shaftesbury Institution is a half way house to freedom - a gradual breaking to the female inebriates of a liberty which experience has shown has always resulted in another lapse from the path of rectitude when the weak one is suddenly ushered into freedom'.[23]

Shaftesbury Home for Babies and Mothers

Between 1913 and 1915 the building was again being used by the State Children's Relief Board, as the Shaftesbury Home for Babies and Mothers.[24] A replacement for the Thirlmere Home for Babies, it was one of a number of homes for infants and unmarried mothers that were intended to combat infant neglect and mortality by promoting breastfeeding and maternal care. Like Thirlmere, the Shaftesbury Home had its own dairy to supply milk.[25] In February 1915 the Home was closed and the organisation transferred to Brush Farm, and became the Eastwood Home for Mothers and Babies.

Shaftesbury Inebriate Institution

Following the closure of the Shaftesbury Home for Babies and Mothers, the site became the Shaftesbury Inebriate Institution for men[26]. Some returned soldiers who had been convicted of minor offences and were not suitable for work on medical grounds were also housed there.

In 1916 a female section of the Inebriate Institution was opened[27] and at one stage it became possible to admit yourself for a fee. In 1919 thirteen men and six women were admitted as voluntary patients, paying for their maintenance.[28]

‘A patient may be ''a paying guest'' for 25/- per week, and live entirely separate from those sent from Government institutions. No regular uniform is provided. Inmates may wear their own clothing. Each has her own bedroom, furnished with bedstead, table, chair, combination, mirror, and, drawer for clothes. But whether 'a paying guest' or a non-paying, all must work. Work keeps the mind occupied, the thoughts from dwelling over much on the craving that takes possession of the inebriate.’[29]

In 1927 remaining occupants transferred to ‘mental hospitals’[30] and by 1929 the institution had officially closed[31]. This was the only state run institution for alcohol and drug offenders of its time.

Final stages of redevelopment

In 1929 the NSW government announced its decision to sell the Shaftesbury lands. It was recorded as being ‘too valuable for its present purposes’[32]. When the reformatory had been established in 1877, the site was relatively isolated and remote. By the beginning of the nineteenth century and the release of the Vaucluse Estate for residential development, this was no longer the case. With the ferry service to Parsley Bay beginning in 1902 and the extension of the tramway from Rose Bay to South Head opening in 1903, public transport made the area much more accessible.

The plan to divide the land into 71 allotments of which 54 were classed as residential was at odds with opinions that suggested that the land belonged to Australia and not Vaucluse. The proposed subdivision provoked strong opinions and architect Leslie Wilkinson pronounced the plan as ‘dreadful’ and ‘forty years behind the times’ and that it was ‘a pity to think of commercialising such a beauty spot’ while Alderman AC Samuel, Mayor of Vaucluse advocated for gardens and lawns on the site.[33]

Ultimately the old reformatory building was demolished in March 1930[34] and the land sold.

In 2018 two private homes sit upon the area that once held the main Shaftesbury Reformatory building. In addition to the residential allotments, a parcel of land was set aside for park purposes and part of this site was later leased to the Vaucluse Bowling Club. A separate piece of land was set aside for what was to become the Vaucluse High School, that operated between 1960 and 2006. The Mark Moran Group subsequently purchased the land and built a retirement/aged care facility which opened in 2016.

References

RB Crosson, The Shaftesbury Institute, Woollahra History and Heritage Society Briefs No.117, January, 1999

GSA Planning, 'Former Vaucluse High School site, Laguna Street, Vaucluse', Demolition and Heritage Impact Statement Report, Markmoran at Vaucluse - Seniors Housing Development No. 2 Laguna Street Vaucluse, Attachment 2, Woollahra council website https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/105239/M._Demolition_and_Heritage_Report_-_Part_3.pdf viewed 15 March 2018

Peter E Quinn, Unenlightened efficiency: the administration of the juvenile correction system in New South Wales 1905-1988, Thesis for Doctorate of Philosophy University of Sydney, January, 2004, University of Sydney Library website https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/623/2/adt-NU20050104.11071502whole.pdf viewed 15 March 2018

Kaye Vernon, 'The Forgotten': Children in Homes, Reformatories and Industrial Schools NSW, Pendeo, Beacon Hill, 2012

Notes

[1] The seventh Earl of Shaftesbury was a social and industrial reformer in 19th century England Amongst other achievements he was president of the Ragged Schools Union that enabled destitute children to be educated free. He also arranged for orphans to be sent to Australia, Wikipedia website, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Ashley-Cooper,_7th_Earl_of_Shaftesbury, viewed 9 March 2018

[2] Shaftesbury Reformatory (1880-1904), series record, State Archives New South Wales website https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/agency/461 viewed 21 November 2017

[3] BILOELA, The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 December 1876, 5, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13392877, viewed 8 March 2018

[4] SOCIAL, The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 March 1880, 7, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13456699, viewed 9 March 2018

[5] Reformatories at South Head, Evening News, 22 December 1876, 2, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article107189122, viewed 9 March 2019

[6] GSA Planning, 'Former Vaucluse High School site, Laguna Street, Vaucluse', Demolition and Heritage Impact Statement Report, Markmoran at Vaucluse - Seniors Housing Development No. 2 Laguna Street Vaucluse, Attachment 2, p 1 Woollahra council website https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/105239/M._Demolition_and_Heritage_Report_-_Part_3.pdf viewed 15 March 2018

[7] EC Rowland, ‘The story of the south arm: Watson’s Bay, Vaucluse and Rose Bay', The Royal Australian Historical Journal and Proceedings, vol XXXVII, Part I, (1951), 229

[8] TENDERS FOR PUBLIC WORKS, New South Wales Government Gazette, 30 November 1877, 4623, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article225827264 viewed 8 March 2018

[9] GSA Planning, 'Former Vaucluse High School site, Laguna Street, Vaucluse', Demolition and Heritage Impact Statement Report, Markmoran at Vaucluse - Seniors Housing Development No. 2 Laguna Street Vaucluse, Attachment 2, p4 Woollahra council website https://www.woollahra.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/105239/M._Demolition_and_Heritage_Report_-_Part_3.pdf viewed 15 March 2018

[10] Sands' Sydney and suburban directory, Sydney:John Sands, 1879, 43, City of Sydney website http://cdn.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/learn/history/archives/sands/1870-1879/1879-part4.pdf viewed 8 January 2018

[11] Peter E Quinn, Unenlightened efficiency: the administration of the juvenile correction system in New South Wales 1905-1988, Thesis for Doctorate of Philosophy University of Sydney, January, 2004, p55, University of Sydney Library website https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/623/2/adt-NU20050104.11071502whole.pdf, viewed 15 March 2018

[12] Shaftesbury Reformatory School (1880 - 1904), Find & Connect website https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01071b.htm, viewed 21 November 2017

[13] Government Gazette Appointments and Employment, New South Wales Government Gazette, 6 February 1880, 594, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article224187967, viewed 9 March 2018

[14] SOCIAL, The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 March 1880, 7, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13456699, viewed 9 March 2018

[15] Mary Salmon, Shaftesbury. The South Head Reformatory. Its Early History, Evening News , 21 January 1908, 2, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article114100128, viewed 9 March 2018

[16] Newtown Police Court, Sydney Morning Herald, 9 May 1882, 7, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13510783, viewed 9 March 2018

[17] Sent to Shaftesbury, National Advocate (Bathurst), 5 August 1890, 3, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156373909, viewed 9 March 2018

[18] Police Court, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 27 February 1897, 2, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article44183589, viewed 9 March 2018

[19] Peter E Quinn, Unenlightened efficiency: the administration of the juvenile correction system in New South Wales 1905-1988, Thesis for Doctorate of Philosophy University of Sydney, January, 2004, 55, University of Sydney Library website https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/623/2/adt-NU20050104.11071502whole.pdf viewed 15 March 2018

[20] State Children Relief Board Report for the year ended 5 April 1901, NSW Votes and Proceedings 1901, v3, 1302

[21] Government School of Housework, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 January 1907, 5, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14842439 ,viewed 9 March 2018

[22] Network of Alcohol and other Drugs Agencies' submission to the Inquiry in the Inebriates Act 1912, https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/committees/DBAssets/InquirySubmission/Body/52665/Submission%2029%20-%20NADA.pdf, viewed 22 November 2017

[23] TREATMENT OF INEBRIATES, The Daily Telegraph, 2 January 1909, 11, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article238202455, viewed 16 March 2018

[24] Shaftesbury Home for Babies and Mothers, Find & Connect website https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01172b.htm viewed 21 November 2017

[25] Mary Salmon, Shaftesbury. The South Head Reformatory. Its Early History, Evening News , 21 January 1908, 2, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article114100128, viewed 9 March 2018

[26] Proclamation, Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales, 10 March 1915, 1508, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page14033715, viewed 9 March 2018

[27] Proclamation, Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales, 21 July 1916, 4177, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article227670988, viewed 9 March 2018

[28] Gaol population, The Daily Telegraph, 4 July 1919, 6, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article239634483, viewed 9 March 2018

[29] The Inebriate Hospital, The Sydney Stock and Station Journal, 9 February 1917, 2, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article124334093, viewed 9 March 2018

[30] Inebriates Home. To be demolished, The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 July 1929, 18, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16564599, viewed 9 March 2018

[31] Proclamation, Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales, 21 June 1929, 2536, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article223022515, viewed 9 March 2018

[32] SHAFTESBURY INSTITUTION. TO BE SOLD AT AUCTION, The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 June 1929, 13, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16558051 viewed 9 March, 2018

[33] VAUCLUSE BEAUTY SPOT: Protest against proposed sale, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 October 1929, 16, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16597211 viewed March 9, 2018; SUBDIVISION OF SHAFTESBURY ESTATE, Construction and Local Government Journal, 30 October 1929, p16, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article109638851 viewed March 9, 2018

[34] VAUCLUSE LANDMARK TO DISAPPEAR, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 March 1930, 14, Trove website http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16636991 viewed 9 March 2018