The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

A venerable old bird

Cocky Bennett, Sea Breeze Hotel, Tom Uglys Point 1911, State Library of Victoria (H23120)

Cocky Bennett, Sea Breeze Hotel, Tom Uglys Point 1911, State Library of Victoria (H23120)

Categories

A Drama of Llamas

Social distancing measures with llamas, Durango Trails, Colorado

Social distancing measures with llamas, Durango Trails, Colorado

Illustration of the animals en route, by Santiago Savage, from a record of Charles Ledger's journeys in Peru and Chile,October 1857, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (MLMSS 630/1)

Illustration of the animals en route, by Santiago Savage, from a record of Charles Ledger's journeys in Peru and Chile,October 1857, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (MLMSS 630/1)

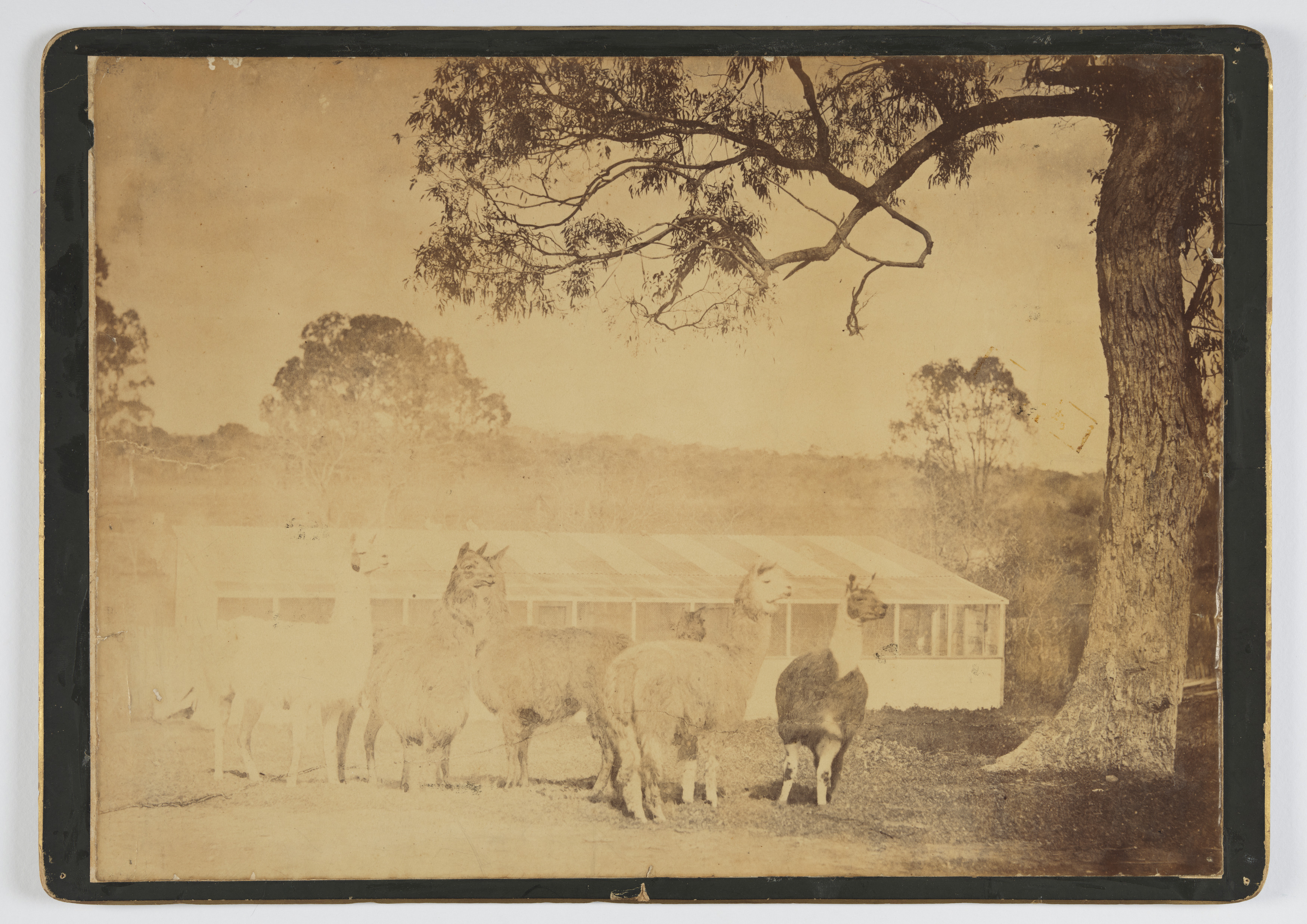

Mr Ledger's alpacas and llamas at Sophienburg, the seat of Mr. Atkinson, New South Wales c1859, National Library of Australia (nla.obj-136096736)

Mr Ledger's alpacas and llamas at Sophienburg, the seat of Mr. Atkinson, New South Wales c1859, National Library of Australia (nla.obj-136096736)

Some of Ledger's flock after their sale in 1863, at Thomas Lee's Bathurst property Woodlands, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (SV/19)

Some of Ledger's flock after their sale in 1863, at Thomas Lee's Bathurst property Woodlands, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (SV/19)

Categories

An excellent establishment

Australian Medical Journal Vol 1 No 4, 2 November 1846, p46, via Trove

Australian Medical Journal Vol 1 No 4, 2 November 1846, p46, via Trove

Listen to Peter and Alex on 2SER here

A devastating and highly infectious disease, smallpox left its victims covered in a rash that resulted in painful fluid-filled pustules that would eventually burst and scab over. With a high mortality rate, survivors usually had terrible scarring all over their bodies. While the colony's strict quarantine measures largely protected the city, there was still risk of an outbreak brought into the country by overseas travellers. Vaccinations against smallpox had been available in Sydney since the first vaccine materials had been imported in 1804, but maintaining a supply of the vaccine material, or 'lymph' in Sydney was difficult. It was often transported between wax-sealed glass slides, or as dried scabs sloughed off a successfully vaccinated patient. However, because its viability declined markedly over time—especially in hot weather—lymph was ideally administered in a fresh state, often by direct arm-to-arm transmission. This was precisely the method used by the colony’s inspector general of hospitals to maintain a small supply of lymph for Sydney in the 1830s. Alarmingly, a sample of this potentially infectious material was found at the New South Wales State Archives and Records in 2010. Stocks were always erratic however, and in the late 1830s it was proposed that a permanent vaccine depot be established. Nothing came of this suggestion, or subsequent ones, until 1846, when the new Governor, Fitzroy, announced the establishment of the Vaccine Institution. Opening in 1847, the Institution's primary purpose was to ‘search in the Town & vicinity for those of the lower orders who have neglected vaccination of their children’ and inoculate these children to lessen their risk of contracting smallpox, should it elude the city’s hitherto successful quarantine defences. ‘It is as much a public sanitary question as the drainage of the city, the Building Act, or the quarantine laws’, asserted Isaac Aaron, the editor of Australian Medical Journal, in the Sydney Morning Herald in October 1846. The Vaccine Institution operated out of the Emigrants’ Barracks in Bent Street, literally around the corner from the Sydney Infirmary and Dispensary that was operating from the southern wing of the General Hospital, and also from the Legislative Council’s chambers, which in 1843 had been constructed in the hospital’s northern wing Sydney Morning Herald, 1 April 1853, p2 via Trove

Sydney Morning Herald, 1 April 1853, p2 via Trove

In this detail from a view of Hyde Park Barracks taken from St James spire in 1872, the words Vaccine Institute can almost be discerned above the entrance in the wall on the right, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXB 419,2)

In this detail from a view of Hyde Park Barracks taken from St James spire in 1872, the words Vaccine Institute can almost be discerned above the entrance in the wall on the right, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXB 419,2)

Categories

A story of escape: a terrible true tale or fake news?

Traveller's engraved horn, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (LR 23)

Traveller's engraved horn, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (LR 23)

Listen to Rachel and Alex on 2SER here

There is a piece of scrimshaw held at the State Library of New South Wales enscribed with text that reads: ‘This horn belonged to Traveller who was calved at Cow Pastures 1819 worked for 12 years at Norfolk Island for Government. Here he was killed by two bushrangers who absconded for purposes of making a boat with his hide to escape from the island on 23rd day of Decr. 1838 - Bennett and Balsto’. It’s a great story, the opposite of the trope of the criminal genius. But how much of it is true? Sure, escape attempts were not uncommon during the convict era, but two blokes thinking they can turn a bull into a boat and make a bid for freedom is unusual. If Bennett and Balsto were trying to escape, then presumably they were convicts. The other side of Traveller's engraved horn, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (LR 23)

The other side of Traveller's engraved horn, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (LR 23)

View of the farm of J. Hassel (Hassall) Esqr, Cow Pastures 1825-28 by Augustus Earle, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (PXD 265, 2)

Government House & Military Barracks Norfolk Island 4th mo: 1835, by George Washington Walker, Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (DL PXX 28 f1)

Government House & Military Barracks Norfolk Island 4th mo: 1835, by George Washington Walker, Dixson Library, State Library of NSW (DL PXX 28 f1)

Categories

Annie Wyatt, heritage warrior

Membership Card No 1, belonging to Annie Forsyth Wyatt, courtesy of National Trust of Australia (NSW)

Membership Card No 1, belonging to Annie Forsyth Wyatt, courtesy of National Trust of Australia (NSW)

Listen to Lisa and Alex on 2SER here

The National Trust of Australia is oldest conservation charity and is committed to the preservation and protection of our built, natural and cultural heritage. The Trust was founded in Sydney in 1945 and now has branches around the country. Based on the heritage conservation organisation that began in the United Kingdom in 1895, it came into being in Australia at a time of great change and development to raise community consciousness of widespread destruction of the Sydney's built and natural heritage. Annie Forsyth Evans with wildflowers at her family's home Girrahween in Manly c1905, courtesy National Trust (NSW), from family album held by Lynnette Lee

Annie Forsyth Evans with wildflowers at her family's home Girrahween in Manly c1905, courtesy National Trust (NSW), from family album held by Lynnette Lee

Annie Wyatt 1941, courtesy National Trust of Australia (NSW Branch)

Annie Wyatt 1941, courtesy National Trust of Australia (NSW Branch)

While the National Trust's celebrations for the anniversary have been postponed for the moment, head to their website (https://www.nationaltrust.org.au/75years/) and follow their social media streams to keep up with their great 75 Stories campaign and to hear the latest about their plans for future festivities.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nationaltrustau/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/nationaltrustau

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nationaltrustnsw/

Dr Lisa Murray is the Historian of the City of Sydney and former chair of the Dictionary of Sydney Trust. She is a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of New South Wales and the author of several books, including Sydney Cemeteries: a field guide. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Lisa, for ten years of unstinting support of the Dictionary! You can follow her on Twitter here: @sydneyclio

Listen to Lisa & Alex here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20 am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

While the National Trust's celebrations for the anniversary have been postponed for the moment, head to their website (https://www.nationaltrust.org.au/75years/) and follow their social media streams to keep up with their great 75 Stories campaign and to hear the latest about their plans for future festivities.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nationaltrustau/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/nationaltrustau

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nationaltrustnsw/

Dr Lisa Murray is the Historian of the City of Sydney and former chair of the Dictionary of Sydney Trust. She is a Visiting Scholar at the State Library of New South Wales and the author of several books, including Sydney Cemeteries: a field guide. She appears on 2SER on behalf of the Dictionary of Sydney in a voluntary capacity. Thanks Lisa, for ten years of unstinting support of the Dictionary! You can follow her on Twitter here: @sydneyclio

Listen to Lisa & Alex here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15-8:20 am to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

Categories

Balmain Colliery

Balmain Colliery c1920 by John Henry Harvey, courtesy State Library of VIctoria (H91.300/71)

Balmain Colliery c1920 by John Henry Harvey, courtesy State Library of VIctoria (H91.300/71)

Balmain Colliery workings to 1931, New South Wales Department of Industry (PRIMEFACT FEBRUARY 2007, 556)

Balmain Colliery workings to 1931, New South Wales Department of Industry (PRIMEFACT FEBRUARY 2007, 556)

Australian Town and Country Journal, 30 November 1901, p 24

Australian Town and Country Journal, 30 November 1901, p 24

A broadcasting party who descended nearly 3000 feet below Sydney Harbour, Sydney Mail, 1 September 1926, p14

A broadcasting party who descended nearly 3000 feet below Sydney Harbour, Sydney Mail, 1 September 1926, p14

Listen to the audio of Mark & Alex here, and tune in to 2SER Breakfast on 107.3 every Wednesday morning at 8:15 to hear more from the Dictionary of Sydney.

Categories

Julian Leatherdale, Death in the Ladies' Goddess Club

Julian Leatherdale, Death in the Ladies' Goddess Club

Julian Leatherdale, Death in the Ladies' Goddess Club

Allen & Unwin, March 2020, p/bk, ISBN: 9781 76052 963 5, RRP AUD$29.99

Death in the Ladies’ Goddess Club by Julian Leatherdale is set in Sydney in the 1930s and follows Joan Linderman, budding crime writer and amateur detective, and her friend and housemate Bernice Becker, writer, bohemian and erstwhile mother. Joan is a young woman who has moved to Kings Cross from Willoughby, where her parents and war-affected brother still live. Joan’s life is in the inner-city suburbs of Sydney, working for The Mirror, and socialising with fellow bohemians and her communist boyfriend, Hugh. Bernice and Joan live in a converted, crumbling mansion, Bomora, the likes of which were once common in Sydney. Their friends are prostitutes, writers and artists, amongst them well-known people of the time, such as Zora Cross and Norman Lindsay. Joan and Bernice are part of an informal bohemian club, 'I Felici, Letterati, Conoscenti e Lunatici' (Happy, Wise, Literary and Mad), wittily shortened by Leatherdale to the ‘Evil Itchies’ (say “I Felici” out loud!). Through their association with the fringes of Sydney society, Joan and Bernice brush with Sydney’s criminal underworld, but when Bernice discovers the gory murder of a prostitute, friend and fellow Bomora resident Ellie, Joan and Bernice become increasingly entwined in real-life crime and investigation. Linked to Ellie’s death is Joan’s rich aunt Olympia’s 'Ladies’ Goddess Club', a secret women’s sex and drug club, into which Joan and Bernice are initiated. In the background is the mystery of Joan’s other brother, James, who never returned from WWI. Their mother's unwavering belief in his survival and return to Sydney threatens to become madness. The story ends with a twist that isn’t entirely unexpected but is still somewhat of a surprise. Overall, it is a neat story that leaves all loose ends tied up, except one. This novel is well-researched and conjures a vivid and authentic picture of Sydney and surrounds in the 1930s. Crumbling old boarding houses converted from once grand homes are equal characters with the people. The police detective, Lillian Armfield, was a real police sergeant at the time, and the lives of well-known Sydney crime figures merge with the fictional. The book’s main themes are writing, authorship, feminism, class and war. The after-effects of WWI on Sydney society inform the novel, how it has affected women’s roles and the post-war battles between the haves and have-nots, and the New Guard versus the Communist Party. Joan and her family are working class, while her aunt and uncle, Olympia and Gordon, represent Sydney’s wealthy elite. The author clearly chooses the side of the working class, and the novel links wealth with corruption, crime and unscrupulousness. Communism and the politics of the era are explored through the character of Joan’s boyfriend Hugh, a war hero and member of the Communist Party. Political figures of the era, Premier Jack Lang and Mrs Lang, Francis De Groot, Governor Philip and Lady Game all make an appearance towards the end of the novel when Joan and Hugh attend the opening ceremony of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The construction of the bridge and the joining of the arches is a backdrop to the novel; and the opening ceremony symbolises a turning point in the novel where Joan discovers a significant clue to the crimes committed. Creative writing and authorship give the novel its structure. Joan is a wannabe crime writer, with the deadline for her first story approaching. Joan writes about the crimes and clues in her life and her own amateur investigations in her novel, from the perspective of her fictionalised (yet real in the novel) Sergeant Lillian Armfield, whom she admires. In the novel, Joan undertakes her own detective work which then feeds back into her writing. Leatherdale writes from Joan’s perspective: ‘How could she persist now that so much had changed, now that she, the writer, was so deeply entangled in the narrative, no longer the detached outsider but a character at the mercy of the story itself?’ (p. 282) And again: ‘The challenge for Joan was to see herself as the woman police officer saw her…' (p. 282) Joan’s story writing is interspersed throughout the novel and serves to summarise the novel’s events. The reason for this is slightly unclear, perhaps a comment on authorship and authority or perhaps Leatherdale’s comment on women increasingly becoming the authors of their own lives. Feminism is loud and clear in Leatherdale’s novel. On page 330, as Joan smashes the inside of Bomora, her former home and due for demolition, her thoughts run: ‘To change men’s minds and build another world for women would require destruction of one kind or another. Did any of the men she knew and loved truly respect her as an independent, capable person?' These ideas form the backbone of the book. Joan rails against the idea of becoming a suburban wife and mother, like her own mother, and her best friend Bernice gave up her two sons to live the life of a bohemian writer. Joan and Bernice’s sexual exploits are peppered throughout the book, and whether or not they are accurate for young women in 1930s Sydney, they have a refreshing honesty, frankness and freedom to them. The plot moves steadily and unfolds at an even pace. I would have liked more build-up and suspense in the threats to and attacks on Joan, in some places they seemed to come out of the blue. I also felt that in some parts of the book Leatherdale could have ‘shown’ rather than ‘told’, particularly in passages of dialogue. Overall, the book is a well-paced, light and enjoyable read evoking a long-gone Sydney. Leatherdale brings his characters and the city of Sydney to life. If you enjoy crime fiction or historical fiction, then this book is certainly worth a few hours of your time. Reviewed by Shari Amery, March 2020 Head to the publisher's website to order and for a preview of the book here.Categories

They had no Shelf Control: book thieves in colonial Sydney

Photo by Su Westerman, via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Photo by Su Westerman, via Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Listen to Rachel and Alex on 2SER here

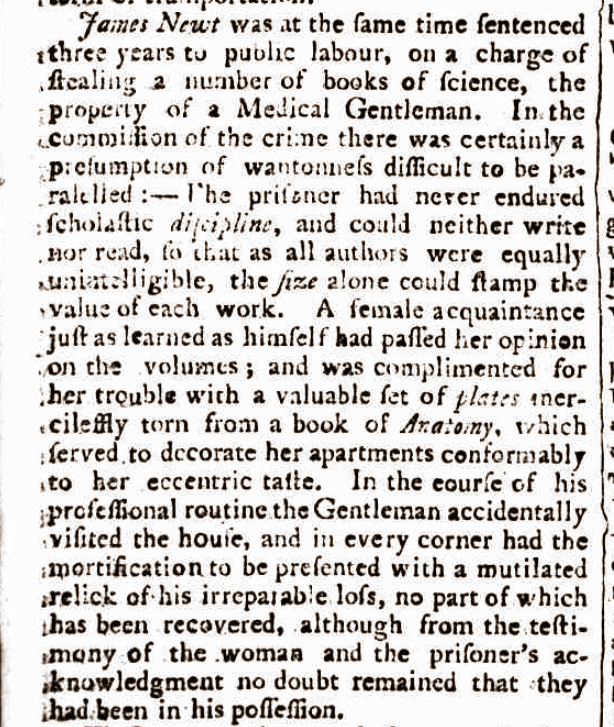

The first case – may I call it a bookcase? – I want to talk about today is that of book thief James Newt who stole some scientific texts in late-1805. The victim was a 'Medical Gentleman', one who drew significant sympathy from the press. Indeed, the newspaper report of the day was scathing of Newt: In the commission of the crime there was certainly a presumption of wantonness difficult to be paralleled: — The prisoner had never endured scholastic discipline, and could neither write nor read, so that as all authors were equally unintelligible, the size alone could stamp the value of each work. Newt orchestrated this heist on his own, but he did manage to entangle a female companion in his crime. In a move that would place his wrongdoing on full display, Newt rewarded a woman – who was 'just as learned as himself' according to the Sydney Gazette – for commenting on the beauty of the books: he gave her, to recognise such good taste, a 'valuable set of plates mercilessly torn from a book of Anatomy.' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 10 November 1805, p2, via Trove

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 10 November 1805, p2, via Trove

Categories

Sydney's smallpox epidemic in 1881

'Small-pox! : a treatise' by D. Kinnear Brown. Sydney: J.G. O'Connor, 1881, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (DSM/614.473/B)

'Small-pox! : a treatise' by D. Kinnear Brown. Sydney: J.G. O'Connor, 1881, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW (DSM/614.473/B)

Listen to Minna and Alex on 2SER here

Tobacco smoke was thought to ward off the risk of infection, Incidents of the Smallpox Scare in Sydney, Australian Town and Country Journal, 25 June 1881 p1282 via Trove

Tobacco smoke was thought to ward off the risk of infection, Incidents of the Smallpox Scare in Sydney, Australian Town and Country Journal, 25 June 1881 p1282 via Trove

Administering the smallpox vaccine to residents of a Surry Hills house through the palings of the back yard fence, Incidents of the Smallpox Scare in Sydney, Australian Town and Country Journal, 25 June 1881 p1282 via Trove

Administering the smallpox vaccine to residents of a Surry Hills house through the palings of the back yard fence, Incidents of the Smallpox Scare in Sydney, Australian Town and Country Journal, 25 June 1881 p1282 via Trove

Profiteering from the sale of disinfectants, Incidents of the Smallpox Scare in Sydney, Australian Town and Country Journal, 25 June 1881 p1282 via Trove

Profiteering from the sale of disinfectants, Incidents of the Smallpox Scare in Sydney, Australian Town and Country Journal, 25 June 1881 p1282 via Trove

Categories

'The difficulties that beset the paths of working mothers'

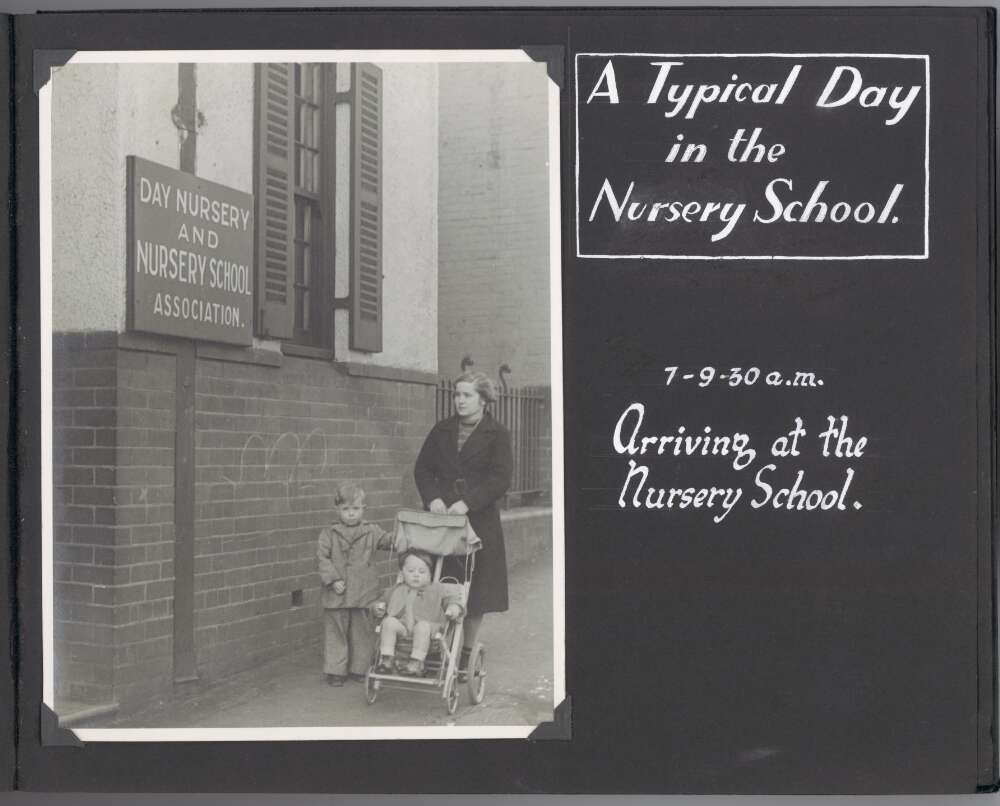

Arriving at nursery school, October 1939, courtesy National Library of Australia (nla.ms-ms2852-19-9x)

Arriving at nursery school, October 1939, courtesy National Library of Australia (nla.ms-ms2852-19-9x)

Listen to Lisa and Alex on 2SER here

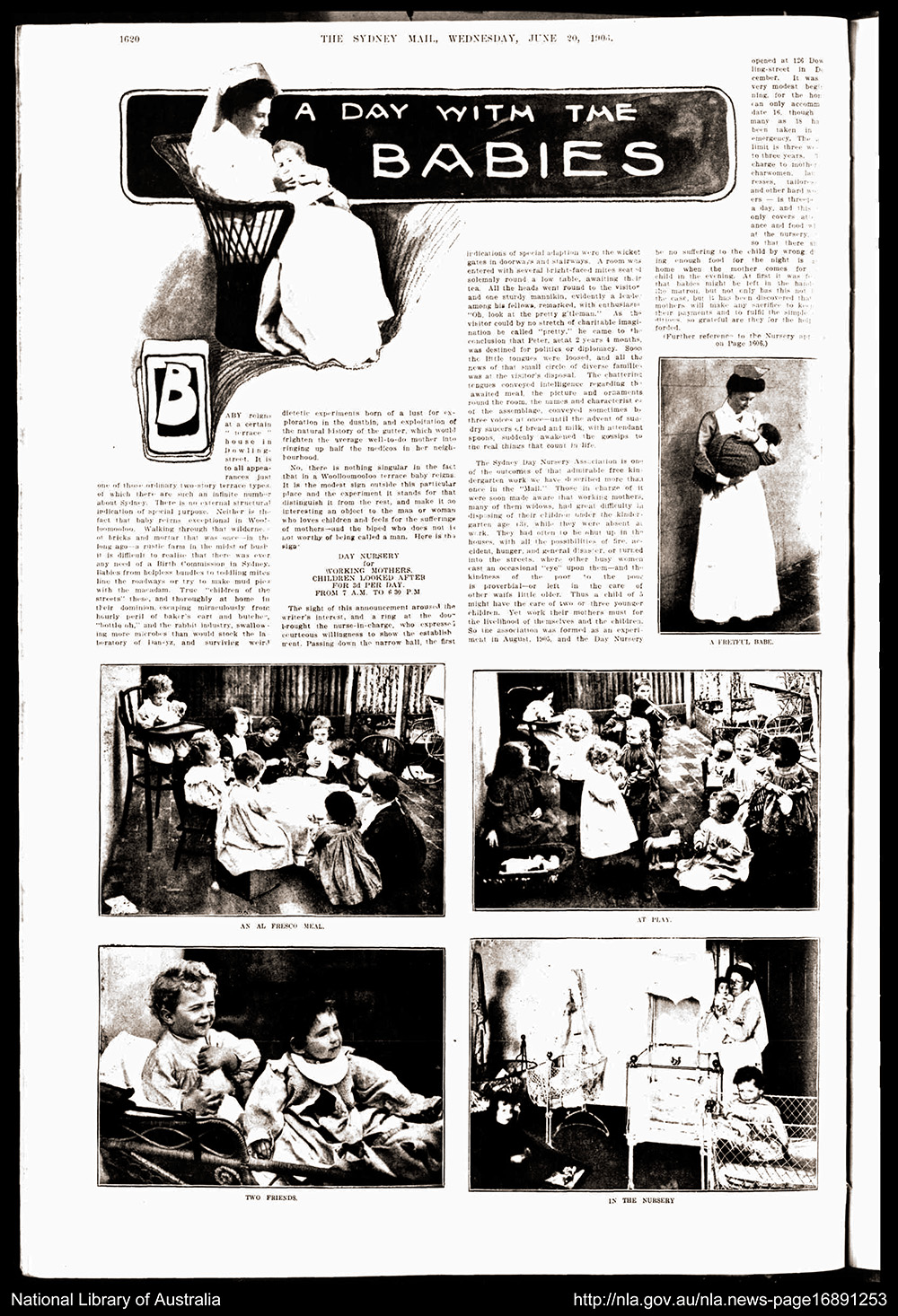

The burden or job of childcare often falls to women. Today working women have a variety of options for childcare: aside from immediate family, there are family day care centres, childcare centres and kindergartens. But for much of the 19th century, women in Sydney were entirely reliant upon family and neighbours, and even their older children, to care for their babies and toddlers while they earned a crust. Only the wealthy few could afford a nanny or domestic servant. It wasn't until 1895 that feminist Maybanke Anderson worked with other female reformers to found the Kindergarten Union. The first Free Kindergarten was set up in Sydney to assist working mothers in Woolloomooloo. In 1903 however, the Kindergarten Union decided to exclude children under the age of three, on the basis that infants required nurses, rather than teachers. This left many poor working mothers in a pickle. Two years later another group of middle-class women, all with business connections and feminist reformist beliefs, got together to found the Sydney Day Nursery Association. They believed a creche was needed to assist working women. It was to be '…no cold, remote charity, but an institution started by fellow women, who fully realise the difficulties that beset the paths of working mothers.' A Day with the Babies, Sydney Mail June 20 1906 p1620 via Trove

A Day with the Babies, Sydney Mail June 20 1906 p1620 via Trove

Categories