The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Suburban Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Suburban Sydney

Sydney has been described as a 'City of Suburbs'. [1] Kilometre after kilometre of suburb has for decades dominated the cultural landscape of Sydney and other Australian capital cities while suburbia has formed the ideology that has been dominant for more than two generations. Metropolitan Sydney's phenomenal suburban expansion during much of the twentieth century has been explored by a small number of urban historians. [2] But the impact and importance of suburbanisation in and around Sydney – by far the largest annual metropolitan investment item – has still to attract the attention it deserves.

Suburban virtues

Some historians of suburban Sydney have embarked on a search for its distinctive cultural virtues. They found the following: privacy, self-sufficiency, respectability, uniformity. In her study of Concord, Grace Karskens observed that the suburb was 'self-conscious and, it appears, secure. Its inhabitants enjoyed its sense of place in a way that no outsider could fully appreciate. [media]In shaping their environment so successfully', she concluded,

suburban people created one of the most early recognisable cultural landscapes… The brick bungalow suburbs of Sydney… are a potent symbol of the culture of ordinary people. They must be allowed to speak for themselves. [3]

At one level this is true. But suburb creation, suburban ideology and suburban existence are more complex. The suburbs were by no means homogeneous. Internally, some, like Concord, combined different social levels that existed somewhere between capital and labour, the middle and upper middle classes. But members of the bourgeoisie and the working classes were also moving to suburbs – such as Strathfield and Lane Cove, and Blacktown and Liverpool, respectively – in various waves during the twentieth century.

Attributing the rise of suburbia to suburbanites ignores the historical contexts and processes which bore on suburban developments and the powerful ideologies that inspired and informed them. These, as Graeme Davison has written, included evangelicalism, which extolled a return to homely virtues; romanticism, which endowed the suburbs with rusticity; sanitarianism, which supposedly purified the environment, underwriting health and happiness; and capitalism. Capitalism generated class tensions and hatreds as well as grim filth and squalor. [media]Suburbs allowed the recipients of the benefits of capitalism to insulate themselves from sites of industry and commerce and to quarantine themselves from 'inferior' classes. Thus the suburbs collectively embodied 'respectable' bourgeois values and standards. But as Davison notes, since the suburb was 'based on the logic of avoidance', its virtues were 'essentially negative': they were exclusive, elitist, restrictive and stuffy. [4]

Reconstructing urban life

Suburbanisation was an element in the reconstruction of social and economic life. The suburbs were integral to the rise of domestic industries and services – tiles, timber, plaster, plumbing, electricity, sewerage – tying wage and salary earners into 'pay-off-as-rent' [5] while providing them with a means for capital accumulation and an alternative to the old age pension. Suburbia also worked to enable class segregation or quarantine. Through the 1919 Local Government [Amendment] Act, local bylaws that restricted certain classes of residential building, and other means, insular environments were created in relatively isolated areas largely for Sydney's middling classes.

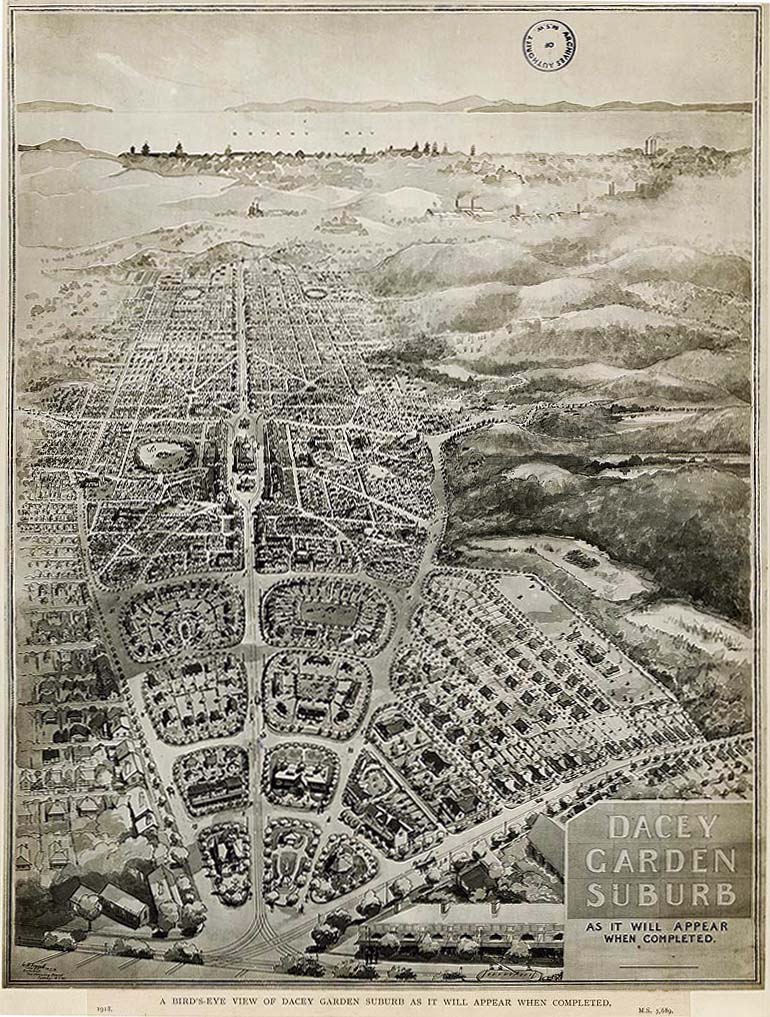

[media]Suburbia also gave expression to religious division, sectarianism and 'wowserism' as well as the pervasive 'White Australia' policy. The outbreak of bubonic plague during 1900 resulted in the razing of numerous blighted, inner-city, working-class residential areas. They were largely replaced by modern warehouses and port facilities. Many reformers held up visions of a utopian metropolitan city which would be 'rich, healthy, and beautiful – a true Commune'. [6] Salubrious, shining suburbs, inspired by the best principles of town planning and filled with homes specifically designed for Australian conditions, were to provide the cradles required to breed up the race for a new social order.

City versus suburbs

While dominant cultural, social and economic discourses of the 1880s and 1890s focused on the 'city and the bush', the 1900s, 1910s and 1920s witnessed the rise of a contest between the city and the suburbs.

In the struggle over cultural dominance and finite resources, proponents of suburbia cast the city as corrupt and retrogressive; a mere engine; a product of 'old world' influences deleterious to the national imperial character and the establishment of a new social order. Fusing civilisation and nature – the best of the city and the country – the respectable suburb was to be the fount for the new race.

[media]The spread of the new suburbia entailed a reconfiguration of social relations and perceptions of class in the process of community formation. The proliferation of social institutions such as progress associations and golf clubs, which were integral to this process, also impacted on the cultural landscape. But it was not the ideals of crusading scientific planners or enlightened politicians and bureaucrats that underpinned these developments. Rather, bourgeois culture, with its characteristically galvanising adaptability, assimilated ideological conflicts, appropriated planning mantras and relocated an expanded antipodean version of the English gentry ideal into an evolving pattern of respectability that became increasingly suburban from the latter half of the nineteenth century. The self-professed heirs of the gentry tradition were to see themselves, and be seen, as steadfast social pillars in a rapidly changing and threatening world.

Suburban values

Questions of national and racial supremacy informed the cultural logic of suburbanisation. Human raw material in the antipodes was said to be the best in the world, a claim that was bolstered by the Anzac legend. And it needed to be isolated from degenerative influences of both mass society and the foreigner. The supposed sources of its vitality were a connection with the land and the inheritance of the yeoman pioneer. Thus, in the face of rapid change and uncertainty, and a struggle to keep Australia white, the sustaining myth of a previous generation – the agrarian myth – was transplanted to the closer-settlement and soldier-settlement allotment and to the quarter-acre block.

With grass and garden, sun, a backyard and vegetable patch, a solid fence, sturdy children and a manageable mortgage promising lifetime security and an assured inheritance, the 'average' suburbanite was held up as a latter-day yeoman. Traditional, organic values – deference, respectability and the Protestant work ethic – were reasserted in a regenerated familial Arcadia. Suburbia – both on the ground and in the mind – became the foundation of the new conservatism which embraced or invented tradition. It is not an accident that the rise of suburban Sydney coincided with the development of the movement for the preservation of historic buildings and the growth of the local historical society. Alongside their homes, community halls and council chambers, suburbanites began constructing their own pasts, linked to an imperial nationalist story, with their own pioneers and special places.

Early suburbia

[media]Sydney had suburbs not long after the European invasion. Sydney Town's first 'genteel' suburb was on Woolloomooloo Hill, later referred to as Potts Point. Here, in the later 1820s and early 1830s, suburban villas – some marine, some in the round – sprang up as the colony's self-styled gentry, in reality a new and powerful officialdom, removed itself from the town. Affecting genteel pretensions, these 'pure merinos' chose suitable names for their grand homes: Tusculum, Bona Vista, Grantham, Springfield, Rose Bank, Orwell. [media]John Claudius Loudon, Scottish horticulturalist and landscape gardener, extolled the virtues of the suburban villa at the height of its popularity at the close of the 1830s. 'The enjoyments to be derived from a suburban villa', he wrote, 'depend principally on a knowledge of the resources which a garden, however, small, is capable of affording.' He also noted the

benefits experienced by breathing air unconfined by those streets of houses, and uncontaminated by the smoke of chimneys, the cheerful aspect of vegetation, the singing of birds in their season; and the enlivening effect of finding ourselves unpent-up by buildings'.

Along with health and recreation, a suburban existence satisfied a 'love of distinction; of retirement; of seclusion'. [7]

[media]Most of Sydney's wealthy merchants, however, located their principal residences in what is arguably the city's oldest suburb, The Rocks. Building mansions along a ridge overlooking Sydney Cove, many of Sydney's leading traders took advantage of views, breezes, good drainage and close proximity to their immediate sources of wealth. Further down the hill, the lower orders lived in crowded and often dangerous conditions close to their places of work. But both Potts Point and The Rocks were administratively within the boundaries of the City of Sydney, and as Sydney grew, they were thought of less as suburbs and more as parts of the city. So too were places like Surry Hills, Chippendale and Darlinghurst – not suburbs but 'inner city'.

Suburbs for the well-to-do

These patterns and themes, in various manifestations and locales, were repeated as the city and its growing metropolis experienced cycles of economic growth and physical expansion or redevelopment. During most of the nineteenth century, however, suburbia was largely a place for the well-to-do, along with those who provided daily services for them. In 1841, for example, only 5534 people (or 4.29 per cent of the total population of the colony) were living in Sydney's suburbs (excluding the older, inner-city areas). By 1891, 275 631 suburbanites appeared on the census (or 24.5 per cent of New South Wales's population, again excluding the inner-city areas). Such growth reflected the rise of middle-class and bourgeois suburbs in the post-gold rush period, particularly in the late 1870s and 1880s.

Getting to the suburbs

The expansion of horse-bus routes had in part facilitated the suburban surge but this was a relatively expensive mode of transport. Unless a suburb was located at a railway platform along a railway line, spare time and a private means of transport were prerequisites for moving out of the city or its immediate environs. Working-class aspirations to own a freestanding or semidetached home on a modest or quarter-acre block were only achievable towards the very end of the nineteenth century. The generalisation and consolidation of the suburbs as the dominant mode of spatial organisation took place after World War I.

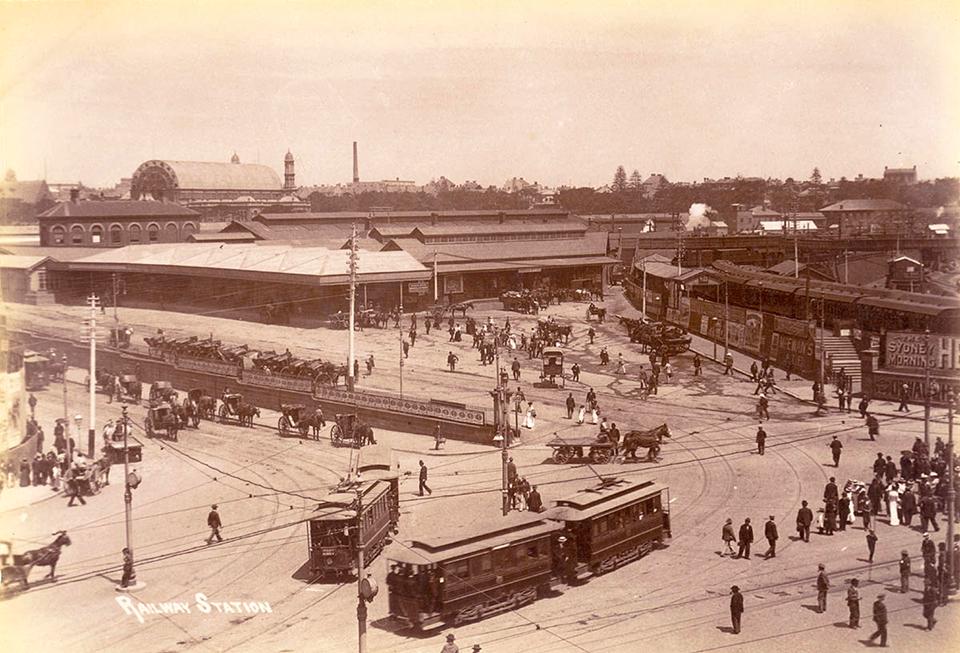

Changes in transportation were critical to the spread of the suburbs. Throughout the industrialising world, major cities experienced a rise in urban mass transportation systems. Sydney was at the forefront of such developments in Australia. Steam had been the dominant form of power in nineteenth-century Sydney. From the early 1900s, steam trams were converted to electric traction as Sydney underwent electrification. And as Audley has rightly argued, the 'emphasis in tramway operation was to provide a service to outer suburbs'. [8] [media]The combination of electric trams and trains – the latter catering mainly for mass commuter movements to and from the City of Sydney –helped drive the expansion of older outer suburbs and villages and the development of new outer suburbs. Ferry commuter numbers were to peak in the 1920s but ferries had a minimal overall impact on suburban growth. The opening of bridges such as that at Iron Cove (opened in 1828 and rebuilt in 1846 and 1882) facilitated expansion. The opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 fuelled suburban development on the North Shore, although much of it remained farms and market gardens until the 1960s.

Growth and change

The spread of the suburbs is reflected in the changing balance between urban and suburban populations. In 1911, census figures reveal that more than a third of people living in the metropolis still resided in the City of Sydney and its adjoining suburbs within walking distance – Glebe, Newtown, Redfern, Paddington, Erskineville and Waterloo. A decade later that figure had fallen to just under one quarter. At the 1933 census only 16 per cent of the inhabitants of greater Sydney lived in the City and its immediately adjoining inner suburbs.

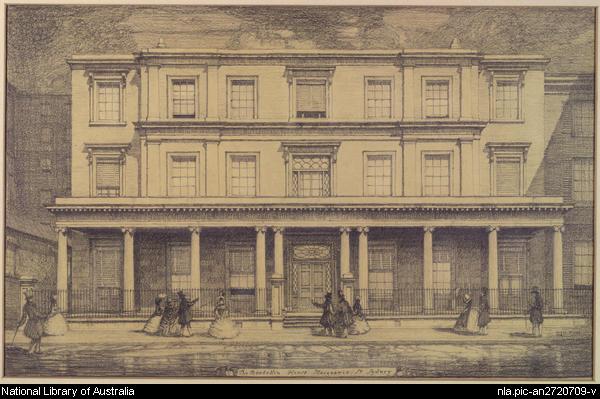

Peter Spearritt has documented and analysed the expansion of the metropolis and the rise of 1920s suburban Sydney in his work Sydney Since the Twenties. Contemporary observers viewed fluctuations in the building industry with great interest and anxiety. It was not simply that they were concerned with monitoring the industry's progress as a measure of capital accumulation. Progress itself – the middle-class ideology, connected to euthenics and the garden city movement and resting on the belief that general material advancement would lead naturally to improved living conditions for all and to the moral improvement of society – was being 'built' in Sydney. While the loss of the familiar was disturbing in many ways, progress was paramount and 'natural'. [media]Writing in 1923 of the proposed demolition of Burdekin House in the City to make way for the modern Hotel Macquarie (in fact it stood until 1933 when it was demolished for St Stephen's Presbyterian church), the publicist for the hotel noted that

another milestone on the road of Sydney's progress is left behind. Ghosts of those days, lang syne, will assuredly accompany us as we speed on. They may, perhaps, gaze wistfully back, but will recognise in this change nature's immutable law, and will wish us success as we, in our turn, journey along. It was ever thus. [9]

Just before World War I, the New South Wales Assessor and Receiver's Office noted in its Annual Report to the Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage that substantial 'evidence of the rapid growth of the city and suburbs is to be seen in every direction'. 'Notwithstanding the remarkable progress', the report observed, the demand for houses was 'as keen as ever, and agents are quite unable to accommodate house-seekers'. A downturn in suburban expansion during the war was followed by residential building activity gradually picking up. In 1922, The Australian Home Builder ran a major, optimistic article entitled 'Building Progress in Sydney'. The best results, it told its readers, had been achieved

in the suburbs of Canterbury, Randwick, Willoughby, Concord, Waverley, and Bankstown. Randwick, Willoughby, and Waverley have in recent years come rapidly to the front as residential areas Randwick and Waverley because of their proximity to the seaside, and Willoughby because of the light air of the North Shore Hills. Canterbury and Concord are, to a large extent, the suburbs of the workers, who, by thrift, have managed to buy their own little homes. Bankstown, formerly a district of large estates, appeals to the man who likes a good-sized vegetable plot attached to his comfortable house. [10]

Building the suburbs

A year later, with a minor boom in progress, the magazine was predicting great things for the building industry and for the apparently ever-expanding suburbs.

[media]Sydney seems likely soon to leave the other Australian cities far behind in rapidity of expansion. Its people grumble savagely about the methods and charges of brick, tile, timber and other 'combines', yet the outlay on new houses, offices and factories this year is already beyond the aggregate reached in any previous period. [11]

Building costs, however, continued to plague 'people of small means who aspire[d] to something better than city tenement life'. Between 1914 and 1923, the average price of a modest four-bedroom brick cottage had risen by 60 per cent from £388 to £649. Concerns were publicly aired over inflated prices for building materials and in 1923 the Master Builders' Association lodged a formal complaint 'against the tile-makers, who... [were] alleged to have added 40 per cent to their prices as a result of combination.' Despite these tensions and barriers to building, suburban expansion in the 1920s was extraordinary. During this decade at least £119,458,641 was invested in new buildings in the suburbs. This represented approximately 81 per cent of all building work on the Cumberland Plain and was equivalent to more than two years of total New South Wales state government average annual expenditure during the 1920s.

Buying and building in suburban Sydney had other meanings. The wave of development that washed over many parts of Sydney leaving cottages, bungalows or art deco mansions in its wake, removed or drastically remodelled earlier cultural landscapes. As the older economic order was replaced, the villas and mansions of the bourgeoisie who had earlier removed themselves from the crowded, dirty city to salubrious locales were pulled down or had their grounds sliced up and sold off.

Keeping the riff raff out

The rate and nature of suburban development in each area depended on a myriad of factors including historical circumstances, geography, politics, group dynamics and individual effort. Class, and the preservation of class distinctions, was another powerful ingredient. Industrial suburbs – such as Auburn – attracted working-class communities. Dormitory working-class suburbs – for example, Dundas – grew near places of work or convenient transport. Lower middle-class and middle-class suburbs such as Concord flourished, spawning mile upon mile of bungalows. Many northern middle-class and bourgeois suburbs strove to exclude others on the basis of class via economic means. Covenants governing types of materials and minimum prices for the erection of homes kept 'undesirables' out. Terraces and weatherboard were banned in places such as Haberfield, as were pubs. State experiments in public housing also had a tendency towards class quarantining. [media]This was clearly evident at Daceyville as well as in the Sydney Harbour Trust's building program for waterside workers in the inner city suburb of Millers Point. Rates of expansion also varied greatly: from a 151.7 per cent increase in housing stock in Bankstown between 1921 and 1933 to negative growth in the city and older suburban areas such as Alexandria and Erskineville where older houses were replaced by industrial and commercial facilities. [12]

The domestic ideal

Whatever the specific characters of different areas, a new domestic ideal had been successfully implanted in the culture during the first two decades of the twentieth century. As perceptions of class became blurred with the rise of mass society, the suburban bungalow, or the more humble suburban cottage, became a symbol of middle-class virtues and values: respectability, individualism, order and material success via hard work and thrift. This was fervently advocated and advanced by real estate agents, speculators, businesspeople – especially those who made buildings materials – and by architects and other 'experts'. This ideology had its roots in the 'liberal political tradition: individualism; 'a stake in the country'; frugal habits; self help. It was to be most clearly articulated a few decades later in Robert Menzies's 1942 radio broadcast, 'The Forgotten People'.

The suburban domestic ideal was also anti-urban. City life, and life in the crammed inner suburbs, enveloped the individual and the family in 'chaotic conditions'. According to the magazine Building, a truly suburban existence meant 'method and order, combining the ideal with the utilitarian, which would culminate in the development of greater civic pride and love of country in the hearts of our city and town dwellers'. Thus the middle-class suburban home, or at least aspiration towards this ideal, was held up to be a civilising influence in an unruly, changing world.

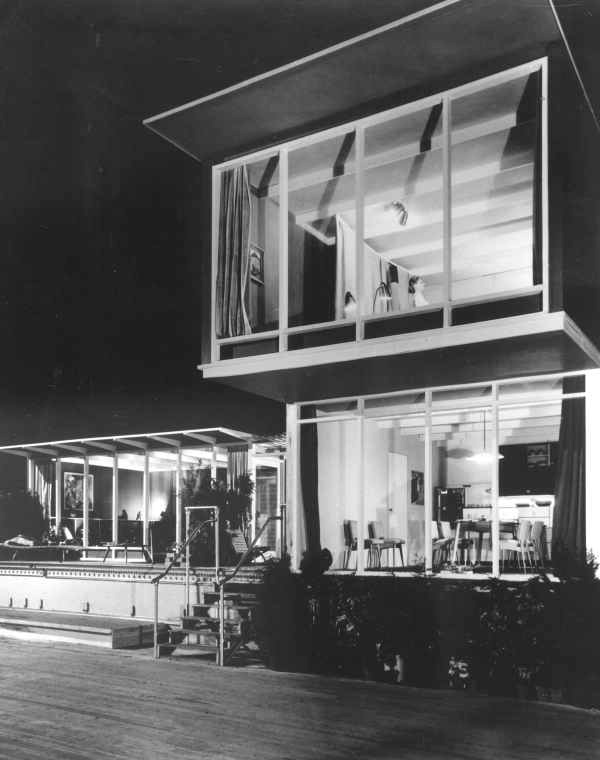

[media]What drove this posturing world – real or imagined or both – of church halls, progress associations, golf clubs, free weekly local newspapers, neatly hedged perimeters and service clubs?

Villages in the city

Unlike cities and towns, which are urban, suburbs have their origins in villages or more often in the village ideal. Suburban villages – such as Beecroft, Lane Cove, Manly, Randwick and Hunters Hill – evolved into select municipalities. These were part of a tradition which created 'subtopias' in Britain along the lines suggested by British town planning pioneer and guru Ebenezer Howard. Using standardised materials and architectural styles, these built-up rural or semi-rural places created a village atmosphere that blurred the boundaries between country and town. They were rustic and generally exclusive.

Residents of these suburbs, most of whom had escaped the city while maintaining investments and economic interests there, sought to control their moral, social and physical surroundings. From the mid-nineteenth century, this was partially achieved through legislation for municipal incorporation and local government by-laws. Suburbanites stressed their local differences and social distinctiveness. Such distinctions were articulated in many ways. In a typical pronouncement, Manly-Warringah District Cricket Club emphasised 'the constant satisfaction that a group of diverse individuals could come together, be infused with the spirit of the game then translate it regularly every Saturday into the attractive and competitive style that is Manly'. Other suburbs, not generated from any prior village nucleus, worked hard to acquire the symbols of a select place – a post office, a school of arts, churches, memorials and a Town Hall.

Suburban villages sought and secured the mantle of respectability and constructed new perceptions of the relationship between the city core and the periphery or frontier. While dynamic, this image essentially cast the city as a sink for the lowest of humanity, as a place of fever, vice, crime, delinquency, deficiency and radicalism. Cities were contaminated by the racial flotsam and jetsam of the process of migration. Dangerous foreigners jumped ship in port cities, harbouring in the nooks and crannies of inner-city slums. Contemporary crime fiction and sensational investigative journalism shone startling lights upon the inner workings of the wretched city. All this, and more, was to be kept out of the untainted suburb.

Suburbs and the intellectuals

Despite their absence or lack of definition in historical representations of Australia, the suburb's impact on antipodean society and culture has fuelled heated debate in some quarters. Suburbs have long been hated, and more recently loved, by Australian writers and intellectuals. They have also been perceived with an uneasy ambiguity, as 'being neither town nor country, but an unwilling combination of both, and either neat and shining, or cheap and nasty, according to the incomes of its inhabitants'. [media]This was the 'half world between city and country in which most Australians lived' that architect Robin Boyd decried in his elitist work on Australian domestic architecture, Australia's Home.

Other intellectuals and observers saw the new self-conscious suburbs as the stuff of nightmares. After spending a week in Sydney in May 1922, DH Lawrence reported, in his novel Kangaroo, of great 'swarming, teeming Sydney flowing out into these myriad of bungalows, like shallow waters spreading, undyked.' Having abandoned Europe as 'moribund and stale and finished' his alter ego, Sommers, had set out for 'a new country. The newest country; young Australia'. But he found the adolescent more problematic than Europe, which quickly gained back its cosmopolitan appeal after his arrival in the antipodes. Here he and his wife found rookish cab drivers, suburban houses with 'impossible names' which 'stood like so many forlorn chicken-houses', dreariness and a seemingly pointless, empty outdoor freedom.

The vacancy of this freedom is almost terrifying. In the openness and the freedom of this new chaos, this litter of bungalows and tin cans scattered for miles and miles, this Englishness all crumbled out into formlessness and chaos. [13]

Though representations of and reactions to suburbanisation varied, a broad range of commentators including radical nationalists, populists, conservatives and new liberals denounced 'the suburb' to the extent that it became a pejorative during the 1920s. Suburbia was also denounced as an expression of that cancerous and degenerate movement, modernism. Writer Nettie Palmer was apprehensive about the spreading, sprawling suburbs. In her work Talking It Over, she pronounced that suburbia was

a variegated monster, presenting you now with brickbats, now with bouquets. [But the] rare and beautiful notes in the cacophony of suburbia may all be happy accidents. One would like to ascribe to accident their opposites – a frightful majority of suburban areas that shall be nameless. If we are to believe that modern suburbia, taken as a whole, expresses the modern mind, what, we ask with trembling, can the nature of that mind be?

WK Hancock – eminent historian, new liberal progressive, 'radical' nationalist and Anglophile – could not see any redeeming qualities in suburbia, which for him symbolised, at best, mediocrity. 'Australians who love their country', he wrote at the end of the 1920s in his book Australia, 'as distinct from the "good conditions" which they may enjoy there – are sometimes tempted to avert their eyes from the spreading rash of nineteenth-century suburbia.'

Hancock loathed the suburbs, where, paradoxically, he was to spend much of his later life. It had no place in his imperial-nationalist vision. Suburbs were artificial, inorganic and, for Hancock, frustrating:

the English visitor... as he passes from suburb to suburb... will be astonished at the broad spread of middle-class comfort… Frequently, the spectacle will make him impatient and uneasy. He has expected to see some evidence of the rigours and heroisms of pioneering, and such a stolid mass of commonplace urban prosperity heaped around the doors of an empty continent will appear to him unnatural, unseemly. The Australians themselves are half persuaded that their urban habits are a crime. [14]

Suburbs in literature

A decade on in his novel Here's Luck, Lennie Lower was to ridicule the suburbanite – 'the earnestly genteel' – and the suburb where 'respectability stalks abroad adorned with starched linen and surrounded by mortgages'. Some later commentators were to be crueller. Patrick White brilliantly captured the process and, to a lesser extent, the logic of suburbanisation from the late nineteenth century into the early 1950s in The Tree of Man. A world had been lost. Set in Castle Hill, the novel describes how the once remote place where 'Parkers' kept a handful of cows 'had become practically a suburb':

The wooden homes stood, each in its smother of trees, like oases in a desert of progress. They were in a process of being forgotten, of falling down, and would eventually be swept up with the bones of those who had lingered in them, and who were of no importance anyway, either no-hopers or old. If the souls of these old cottages disturbed, any uneasiness can almost be excluded from the brick villas simply by closing windows and doors and turning on the radio. The brick homes were in possession all right. Deep purple, clinker blue, ox blood, and public lavatory. Here the rites of domesticity were practised, it had been forgotten why, but with passionate, regular orthodoxy, and once a sacrifice was offered up, by electrocution, by vacuum cleaner, on a hot morning, when the lantana hedges were smelling of cat. [15]

In the suburbs, for White, there was little room, if any, for 'moments of illumination'. From the late 1950s, the well-settled denizens of middling suburbia were to provide satirists with material for new, comic Australian archetypes. Recently, however, there has been a strong and growing interest in delineating the origins and complexities of the suburban experience rather than simply denouncing or defending the suburbs.

Suburbs and the long postwar boom

Despite their critics, the suburbs expanded enormously during the long boom after World War II. Soon after the war, owner-builders eagerly constructed modest suburban cottages. They were followed from the late 1950s by project builders. Depression and war had left a wake of housing shortages and stimulated the desire for a 'nest'. But wartime rationing of building materials lingered until well into the 1950s and young working-class couples struggled in early married life to establish a home. These conditions generated political rhetoric. During 1946, the Liberal Party placed an advertisement in popular publications such as the Australian Women 's Weekly asserting that people

can't live in a house of dreams… we want Bricks and Mortar NOW. Our house of dreams – huh! It has become a nightmare of waiting – an agony of muddling and make-believe. If talk and controls build houses, we'd all be living in mansions… We want a Government that will be strong enough to stimulate action, far-sighted enough to plan ahead, enlightened enough to encourage free enterprise. [16]

Planning for the dream home would increasingly take into consideration cars, television (from 1956), American-style freeways and shopping centres, with Sydney's first such centre opening at Top Ryde in 1957. But for some suburbanites, a nightmare lay ahead in an isolated house in a sprawling suburb. In his study of insanity in New South Wales, Medicine and Madness, Stephen Garton observed that in 1880 the 'typical lunatic… was a man. By 1940 the typical patient was a woman… The women patients of 1940 were most often suicidally depressed domestic servants or housewives, living in a Sydney suburb'. [17]

At the beginning of the 1960s just over one fifth of Australia's population lived in suburbs in metropolitan Sydney. As Ashton and Waterson note in their historical atlas, Sydney Takes Shape, postwar immigration was turning Sydney into a multicultural city. Class and sometimes religion had previously characterised many localities. Working-class communities predominated in the western and inner southern suburbs. Wealthier groups resided on the North Shore and in the eastern suburbs. [media]New ethnic groups made homes in certain areas. The largest of these were Italians who moved into Drummoyne, Five Dock, Leichhardt and Ryde; Greeks whose numbers grew in Newtown and Kensington; Maltese in Holroyd and Merrylands; and Yugoslavs at Stanmore. Croatians, Poles, Russians and Ukrainians settled in Fairfield and Lidcombe, finding factory work in these suburbs.

In 1965, Sydney's population reached 2,491,320; this had grown to 3,257,500 in 1980. Since the 1980s the majority of Sydney people born overseas have lived in southern suburbs characterised by medium- to high-density housing. A significant proportion have also made their homes in some south-western and western suburbs such as Lakemba, Wiley Park, Punchbowl, Bankstown, Cabramatta and Fairfield. Individual and collective circumstances and experiences shaped patterns of settlement. Economic considerations, however, influenced considerable numbers of recently arrived migrants to buy or rent homes on the outskirts of the metropolitan area along with Australian-born families with low socio-economic status.

Suburbs and the historians

Amateur historians commenced recording the history of their localities as part of the process of creating suburban identities. Typically they deal with Aboriginal occupants (generally pre-contact), civic endeavour and advancement, the getting of infrastructure, wars, progress and local heroes. Academics historians became attracted to Sydney's suburbs from the 1970s. Hugh Stretton praised suburban life in his book Ideas for Australian Cities (1970). Max Kelly wrote the first scholarly history of a Sydney suburb, Paddock Full of Houses: Paddington 1840-1890, published in 1978. Kelly's book demonstrated the urban cycle of renewal and decay. Paddington was the haunt of some of Sydney's gentry in the mid-nineteenth century. Remnants of this period include the now restored Juniper Hall. Estates in the locality were subdivided in the 1870s and 1880s; the middling classes moved in, made money and moved out to more salubrious suburbs as the area declined and turned, by the end of the 1890s depression, into a 'slum'. In the second half of the twentieth century, however, this process was reversed. By the end of the 1970s, Paddo was well on the way to becoming a chic, inner-city suburb with outstanding heritage and property values.

The future of suburbia

Inner and middle ring suburbs were to experience other pressures from the 1980s as urban infrastructure began to falter and land prices soared. A key governmental response to this was the promotion of 'urban consolidation'. This process accelerated during the 1990s. At the end of the twentieth century, rhetoric about urban planning and visions for the future of Sydney can be read as a crude echo of the calls for a New Social Order and 'national efficiency' at the century's beginning. Unlike national efficiency which had, at least initially, a radical, transformative social agenda at its heart, urban consolidation is essentially an exercise in economic rationalist belt tightening. Extolling the 'compact city' and higher density block, town and row housing, advocates of urban consolidation would have shocked early town planners who equated such conditions with slum creation. The long-gone promoters of national efficiency, who argued the need for state intervention to civilise capitalism, would have also lamented the seeming return to laissez faire. Under economic rationalism, the logic of the market provides the basis for suburban and urban development policy.

The new 'efficiency' movement looks to small government, user pays, individual choice and consumer-driven decision making. The ability to make 'lifestyle choices' is assumed at the expense of the realities of class, disability, gender and race. Efficiency has also been made an end in itself.

Well-to-do suburbanites in 'first-class' (or residential A) areas waged municipal battles during the 1990s to keep out row and town housing. Pressures on the suburbs and inadequate facilities and amenities saw a movement amongst the privileged classes back into the old inner suburbs. There, restrictions and surveillance have increased. Private security firms are employed by corporations to watch over recently gentrified locales while some of the new, well-to-do inner suburban residents engage small, private police forces to patrol 'their' streets and calm their fears of disturbing, dispossessed flotsam – people who are not like them.

Others search for the 'good life' in outer, car-dependent, sprawling suburbs. Some find it. Sydney has not yet significantly developed the Los Angeles-style 'private communities' that have garden signage warning unwanted intruders of instant armed responses by hired security. But suburban expansion has contributed to crises in Sydney's urban regional catchment areas. Each utopia has a counter dystopia.

References

Paul Ashton, The Accidental City: Planning Sydney Since 1788, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1993

Paul Ashton and Duncan Waterson, Sydney Takes Shape: A History in Maps, Hema, Brisbane, 2000

P. Beilharz, M Considine and R Watts, Arguing about the Welfare State: The Australian Experience, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1992

Robin Boyd, Australia's Home: Why Australians built the way they did, Penguin, Ringwood, 1978 (first published 1952)

Judith Brett, Robert Menzies' Forgotten People, Sun, Sydney, 1992

Susan Bures, The House of Wunderlich, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 1987

CW Cheape, Moving the Masses: Urban Public Transit in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, 1880-1912, Cambridge University Press, Massachusetts, 1980

Peter Cochrane, Industrialization and Dependence: Australia's Road to Economic Development, 1870-1939, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1980

Nora Cooper, 'Creating a New Type of Suburb in Australia: The Walter Burley Griffins and their Experiments in Home Building in Castle Crag', in The Australian Home Beautiful, vol 7, no 10, 1 Oct 1929, p 14

Graeme Davison, 'The past and future of the Australian suburb', Polis, no 1, February 1994, pp 4–9

Sarah Ferber, Chris Healy and Chris McAuliffe (eds), Beasts of Suburbia: Reinterpreting Cultures in Australian Suburbs, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1994

Shirley Fitzgerald and Chris Keating, Millers Point: The Urban Village, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1992

Robert Freestone, Model Communities: The Garden City Movement in Australia, Nelson, Melbourne, 1989

Stephen Garton, Medicine and Madness: A Social History of Insanity in New South Wales 1880-1940, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 1988

SL Goldberg and FB Smith (eds), Australia Cultural History, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1988

WK Hancock, Australia, Ernest Benn Limited, London, 1945 (first published 1930)

Ebenezer Howard, Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, Swan Sonnenschein, London, 1898

Kenneth T Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, Oxford University Press, New York, 1985

Grace Karskens, 'A Half World Between City and Country: 1920s Concord', in Kelly (ed), Sydney: City of Suburbs, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 1989 pp 144–5

Christopher Keating, On The Frontier: A Social History of Liverpool, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1996

Max Kelly (ed), Sydney: City of Suburbs, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 1989

Max Kelly, Paddock Full of Houses: Paddington 1840-1890, Doak Press, Sydney, 1978

DH Lawrence, Kangaroo, Penguin, Ringwood, 1983 (first published 1923)

John Claudius Loudon, The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion, the author, London, 1838

Lennie Lower, Here's Luck, Eden Paperbacks, Sydney, 1989, (first published 1930)

Metropolitan Board of Water Supply and Sewerage, Twenty-Seventh Report, New South Wales Legislative Assembly, Government Printer, Sydney, 1914

Nettie Palmer, Talking It Over, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1932

Hal Porter, The Watcher on the Cast-Iron Balcony: An Australian Autobiography, Faber and Faber, London, 1963

Tim Rowse, Australian Liberalism and National Character, Kibble Books, Melbourne, 1978

Peter Spearritt, Sydney Since the Twenties, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1978

Peter Spearritt, Sydney's Century, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 2000

Brian Stoddart, Saturday Afternoon Fever: Sport in the Australian Culture, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1986

Hugh Stretton, Ideas For Australian Cities, the author, Adelaide, 1970

The Australian Home Builder

Peter Webber (ed), The Design of Sydney: Three Decades of Change in the City Centre, Law Book Company, Sydney, 1988

Patrick White, The Tree of Man, Eyre and Spottiswoode, London, 1956

Garry Wotherspoon (ed), Sydney's Transport: Studies in Urban History, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1983

Notes

[1] Max Kelly (ed), Sydney: City of Suburbs, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 1987

[2] Peter Spearritt, Sydney Since the Twenties, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1978, Peter Spearritt, Sydney's Century, University of NSW Press, Sydney 2000

[3] Grace Karskens, 'A Half World Between City and Country: 1920s Concord', in Kelly (ed), Sydney: City of Suburbs, University of NSW Press, Sydney, 1987, pp 144–5

[4] Graeme Davison, 'The past and future of the Australian suburb', Polis, no 1, February 1994, p 4

[5] Lennie Lower, Here's Luck, Eden Paperbacks, Sydney 1989, p 152, (first published 1930)

[6] The Sunrise, 1912, quoted in Paul Ashton, The Accidental City: Planning Sydney Since 1788, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1993, p 44

[7] JC Loudon, The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion, the author, London, 1838, pp 1, 33

[8] Dick Audley, 'Sydney's horse bus industry in 1889', in Garry Wotherspoon (ed), Sydney's Transport: Studies in Urban History, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1983, p 99

[9] Rose Publicity Services, Hotel Macquarie, Sydney, 1923, p 2

[10] 'Building Progress in Sydney', The Australian Home Builder, no 2, November 1922, p 56

[11] 'Editorial Notes', The Australian Home Builder, no 6, November 1923, p 26

[12] Paul Ashton, 'Reactions to and Paradoxes of Modernism: The Origins and Spread of Suburbia in 1920s Sydney', PhD thesis, Macquarie University, 1999, Table 1.1

[13] DH Lawrence, Kangaroo, Penguin, Ringwood, 1983 (first published 1923), pp 33, 18, 31, 33

[14] WK Hancock, Australia, Ernest Benn Limited, London, 1945 (first published 1930), pp 157–8,

[15] Patrick White, The Tree of Man, Eyre and Spottiswoode, London, 1956, pp 408–9

[16] Australian Women's Weekly, 11 May 1946

[17] Stephen Garton, Medicine and Madness, University of NSW Press, Sydney 1988, p 1

.