The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

City Underground

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

City Underground

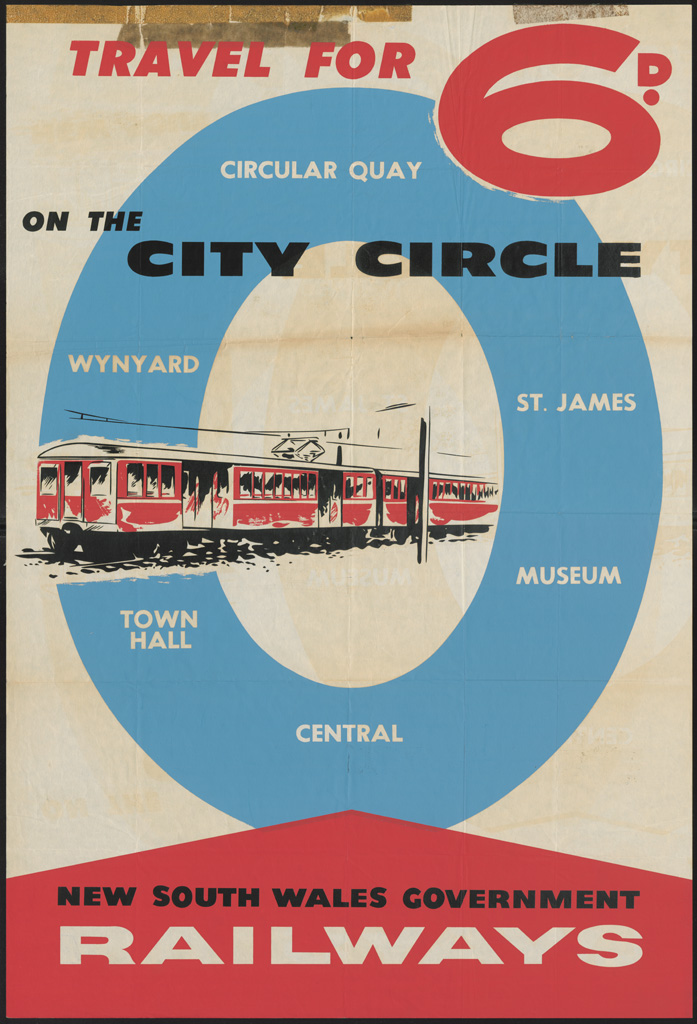

[media]The creation of a city railway was a central concern for town planners in Sydney from almost the moment that the first railway was opened in 1855. Initially the main terminus was in Cleveland Paddocks on the outskirts of the city, meaning commuters coming into town were required to alight from the train and transfer to trams, hansom cabs or omnibuses to continue into the city. The underground City Circle, and the city as we know it, took one hundred years to be completed.

First proposals

The earliest suggestion for the extension of the railway into the city came in 1857 when the Engineer-in-Chief John Whitton proposed an extension to Hyde Park, with others calling for the railway to meet the docks along Darling Harbour, at Circular Quay, or even at the head of Woolloomooloo Bay.[1]

Throughout the rest of the nineteenth century and into the first years of the twentieth century, the question of moving the terminal and extending the lines through the city continued to arise. Three Royal Commissions, three special enquiries, two consultant reports, an Advisory Board and a Commissions report all dealt with the issue between 1890 and 1912.[2] With each scheme various suggestions were put forward but none were pursued until 1906 when the first stage of a new central station was opened closer to, but still outside, the city. Although an improvement this still left the need for a connection to the growing central business district.

The Royal Commission on Communication between Sydney and North Sydney in 1908 and the Royal Commission on City Improvements in 1909, presented the first co-ordinated government strategy for a Sydney transport system, with a Sydney Harbour crossing and an extended railway network at its core. The recommendation for the construction of an underground railway loop through the city was the first time such a plan had been mooted.[3]

JJC Bradfield's plan

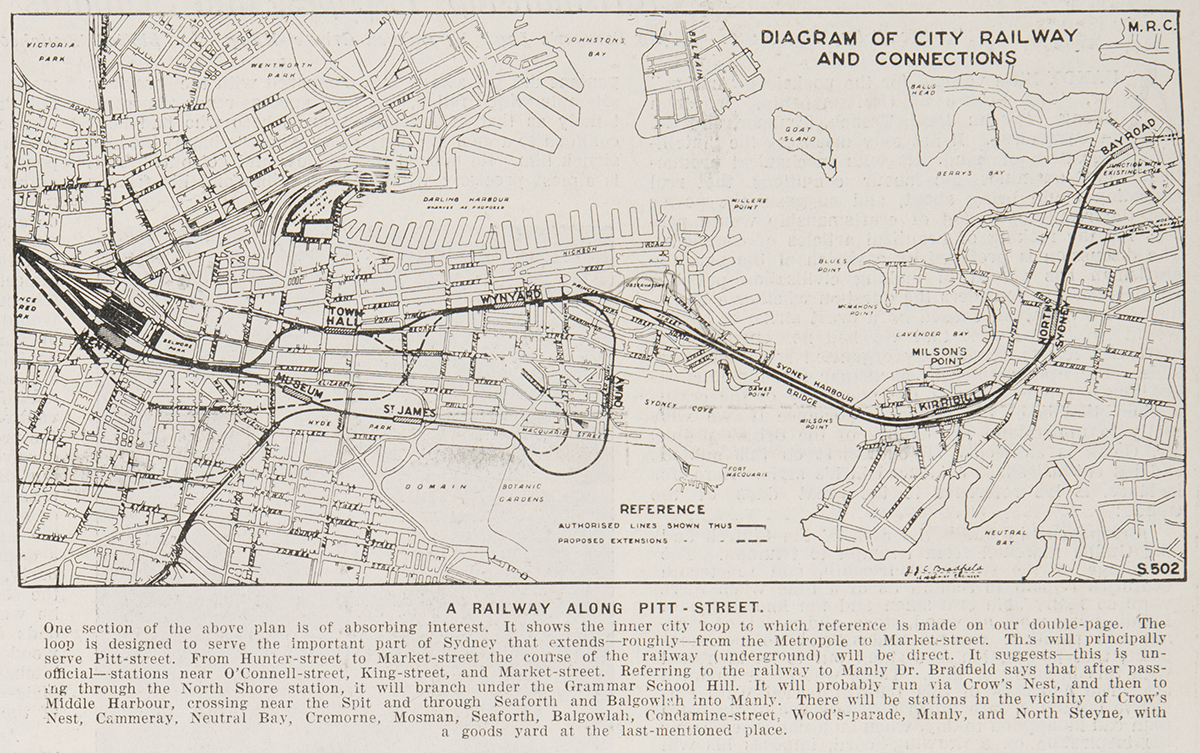

[media]In 1911, John Job Crew Bradfield, an engineer in the New South Wales Department of Public Works, put forward plans to the Public Works Committee for a high level bridge and railway connection across the Harbour and an underground rail loop for the city. The Committee approved of Bradfield's plan and in 1914 he was appointed Chief Engineer, Metropolitan Railway Construction. The following year the government successfully passed the City and Suburban Electric Railway Bill, although the increasing commitment to and associated expense of World War I meant that work ceased in 1916 and legislation for the bridge was not passed until 1922.[4]

[media]Although Bradfield's plan included the city loop, an eastern suburbs line and a western suburbs line carried on a bridge to Balmain, the city loop was prioritised. Bradfield envisioned five city stations, with a through connection to North Sydney via a bridge. The loop design would avoid the delays that any terminating service would cause. His vision was ambitious, with up to 40 trains per hour per line, increased to 80 per hour for stations with their double or bifurcated platforms, and an estimated total of between 36,000 and 42,000 passengers per hour. His plan included the termination of the Balmain line at Wynyard and the eastern suburbs line at St James Station.[5] Bradfield stressed the need for his service to run on a different set of lines than those already terminating at Central Station, which established two services: a city service and a country or intercity service. Power for the system was to be supplied from the White Bay Power Station, then in use for the tramways, with a series of substations around the network.

Work begins

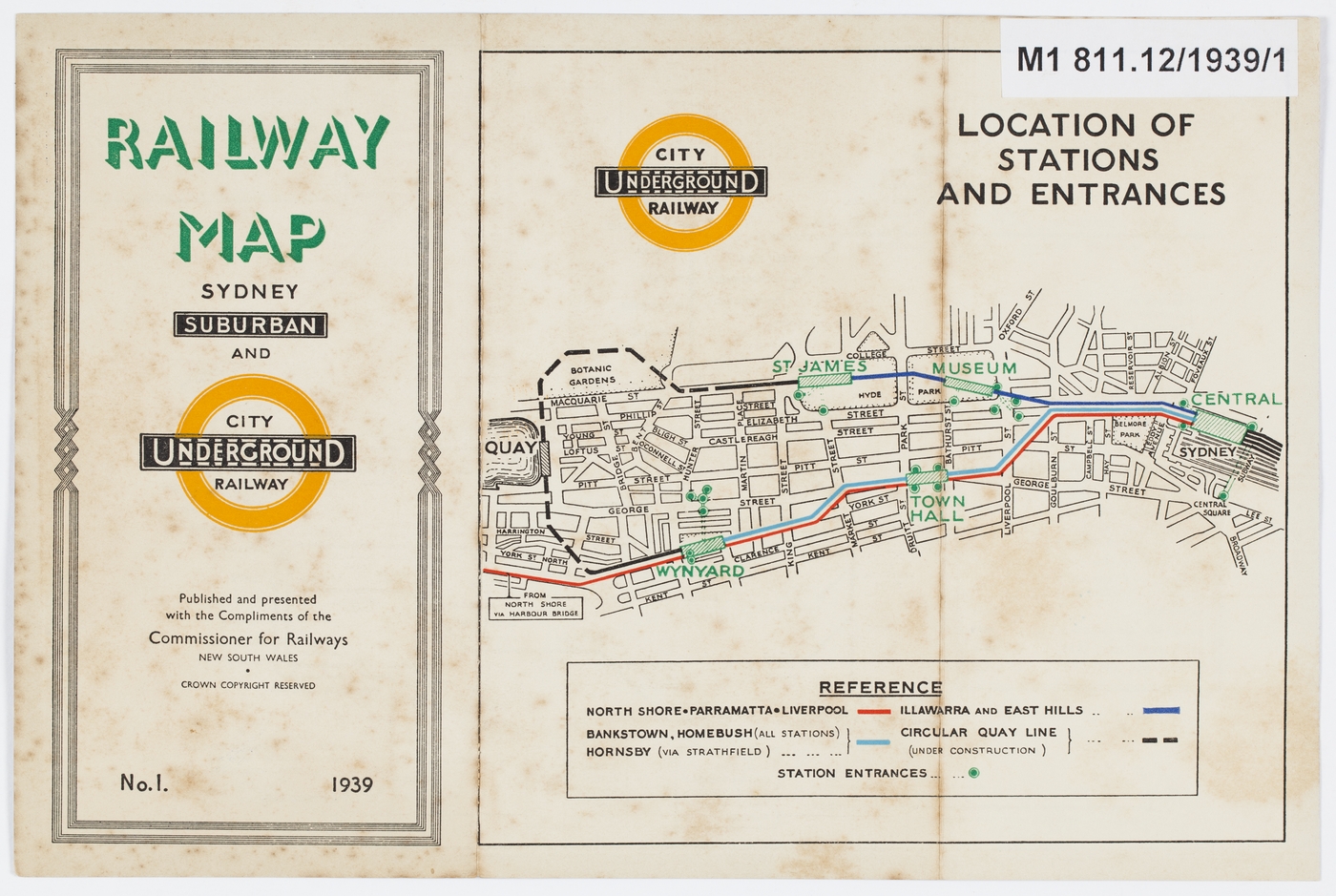

[media]With legislation for the bridge secured, work began in earnest on the railway that would connect to it. The scale of works was to be enormous and caused considerable disruption to the city for the next ten years. The work included four underground stations with two to be built with single levels – Museum with two platforms and St James with four – and the other two to have six platforms over two levels (Town Hall and Wynyard). A new electric station at Central was also to be built.

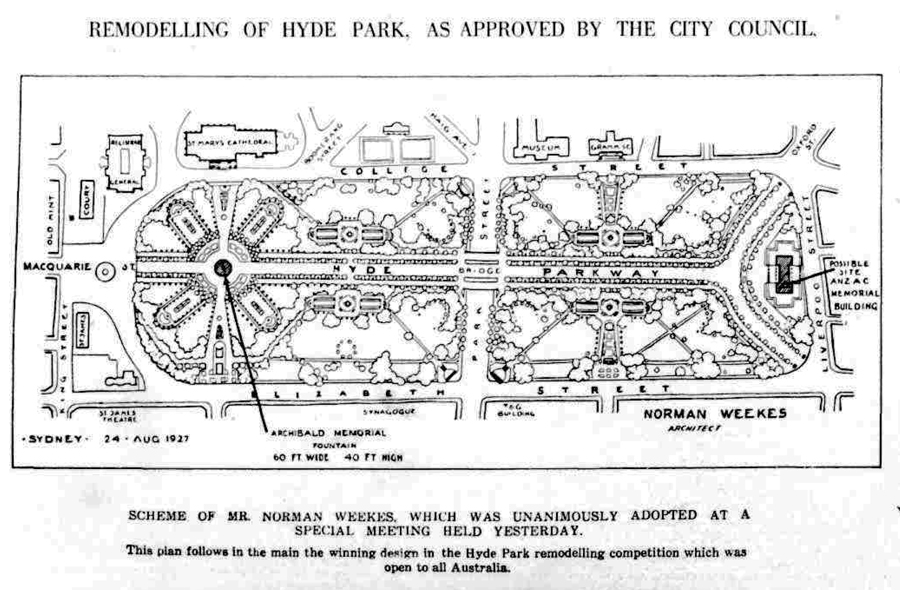

[media]The first section started was the eastern portion of the loop between Central Station and St James Station at the northern end of Hyde Park and then on to Circular Quay, where it terminated in a dead end tunnel. With tunnelling work between Goulburn Street and Hyde Park, a cut-and-cover method was then employed. This involved the removal of much of the park down to the track level, with the infrastructure for the tracks, the electric wiring and the stations built before being covered over and the park, for which Norman Weekes had won a design competition, re-installed above. The excavated material was used to build up the southern approaches for the Harbour Bridge as well as tipped into Darling Harbour to reclaim more land.[6] By mid-1925 much of the formwork, the arches for the stations, the connecting pedestrian tunnels and the platforms at Central were close to completion and work began on the western side.

The public keenly followed the construction of the railway in the press. Crowds gathered to watch the excavations in Hyde Park, while the city newspapers both praised the work and criticised the time it was taking and the disruption to the city.

Opening Museum and St James

[media]The first section between Central and St James opened for trains with little fanfare on 9 December 1926, with only workers at the station to cheer it in. The passengers on board included the Chief Commissioner for Railways and Bradfield with his two sons, Keith and Stanley. The train was driven by Mr RD Stephen, who had served in the railways and tramways for many years and had been the driver of the first electric tram in Sydney as well.[7] The first passenger trains ran on Monday 20 December, with a 4.56am service from St James to Mortdale. As with the trial there was little fanfare, with 60 passengers getting on at St James, but none at Museum. It was reported however that some grasped the significance of the moment, with a number of passengers buying two tickets: one to use and one as a souvenir.[8]

[media]With the first sections opened, work concentrated on the more technically difficult western section, with the vast majority requiring deep tunnelling under city buildings. This section, including Town Hall and Wynyard stations, was progressed to correspond with the opening of the Harbour Bridge in 1932. Work on the stations began in late 1925, with excavations at Wynyard Park underway. The site for the station at Town Hall was enclosed by a fence, with excavations starting the following year. Both stations were built using a steel framework and were designed to take multiple lines with each serving the city loop line as well as north shore lines. At Town Hall station there was also provision for platforms and tunnels at a deeper level to serve a proposed eastern suburbs line. By mid-1927 excavations for both stations were well underway, with the tunnels between both also under construction. As Wynyard Station progressed, work also started on a new headquarters for the railways, to be constructed over the station.[9]

Opening Town Hall and Wynyard and Circular Quay

The stations at Town Hall and Wynyard, as well as the tunnelling between them, were completed in late 1931 and opened to the public on 28 February 1932, just three weeks before the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The opening of the Bridge on 19 March was also the day the first train ran across it with passengers. A special train left Wynyard at 12.30pm with official guests and 600 passengers to North Sydney, before returning to Wynyard. Regular passenger services began the following day.[10]

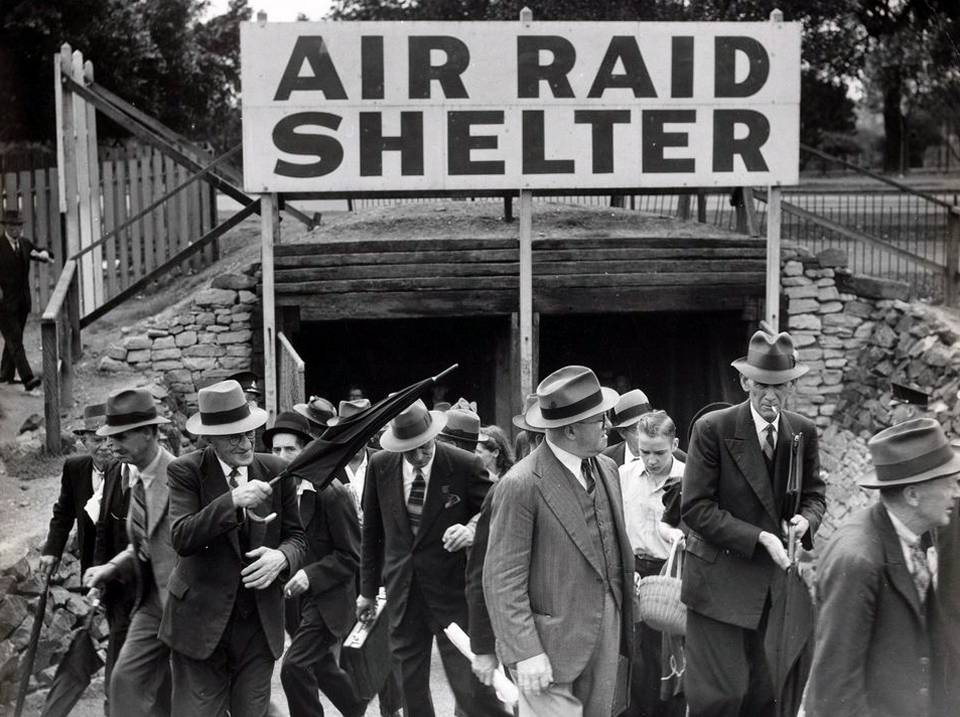

[media]Although Bradfield had advocated for an elevated railway station at Circular Quay as an integral component of his city loop, costs and the outbreak of World War II meant the completion of his dream was postponed. The tunnels were used during the war however as public air raid shelters at St James (parts of which remain in the disused tunnels at the station) and as secure control centres for the armed forces at the Circular Quay end. Although preliminary planning had begun in 1936, it was not until a new supervisory committee was formed in 1948 that plans were finalised. [media]The station would now include a roadway overhead for a new expressway connection to the Harbour Bridge. The original concept for a solid-wall design station building was also modified to a more open plan with views through at ground level and track level to and from the Harbour.[11] Work began on the viaduct to carry the tracks and the roadway in 1946. The station was finally opened on 20 January 1956, with the first regular service around the completed city loop running two days later.

Station design and the impact on the city

[media]Except for the functionalist style of the Circular Quay station, the interiors of each of the new underground stations presented a uniform architectural language of art deco detailing, colour-coded wall tiles and high quality finishes and features. Each of the stations was tiled throughout, with cream body tiles common to all, but with coloured top and bottom courses distinctive to the individual stations. Museum Station was red, St James green, Town Hall yellow and Wynyard blue. The tiling was part of Bradfield's scheme to assist passengers to easily identify the stations.

The construction of the underground also included Railway House (also called Transport House) above Wynyard Station, which was built to consolidate all the railway departments that had previously been at Central. The new, modern office building reflected the growing confidence of the railways and the modern system that was being built, and like the stations, was clad in green terracotta tiles in the same colour scheme adopted for Sydney's ferries, buses and trams.[12]

[media]In the city itself, the new underground led to the repositioning of the shopping district away from Central, where department stores had previously clustered, to the centre of the city around Market and Elizabeth Streets, along George Street and close to Wynyard. David Jones, Farmers, and Gowings all built new landmark buildings, and the Peapes, Mark Foy's Ltd and Marcus Clark & Co stores were all renovated to take advantage of the new underground system and the trade they delivered. These all thrived at the expense of those located close to Central, which was increasingly bypassed.[13]

While the stations have undergone a series of upgrades and extension, most notably with the opening of the Eastern Suburbs line in 1979, which included new platforms at Town Hall and a new station at Martin Place, the system has remained largely faithful to Bradfield's initial vision. More than just an infrastructure project, the underground system was part of a great social and political movement to improve Sydney's amenity and helped transform Sydney from a nineteenth century city to a modern metropolis.[14]

References

Churchman, GB. Railway Electrification in Australia and New Zealand. Sydney: IPL Books, 1995.

Dornan, SE and RG Henderson. The Electric Railways of New South Wales: A brief history of the electrified railway system operated by the New South Wales Government 1926 to 1976. Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1976.

Ferson, M & M Nilsson, eds. Art Deco in Australia: Sunrise over the Pacific. Sydney: Craftsman House, 2001.

Gibbons, R. 'The "Fall of the Giant": trams versus trains and buses in Sydney, 1900–61'. Sydney's Transport: Studies in Urban History edited by Gary Wotherspoon. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1983.

Lee, R. Transport: An Australian History. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010.

McGregor, Gary and Bob Hammer. '100 years of metropolitan rail strategy in Sydney. Lessons for the 21st century'. CORE 2016: Maintaining the Momentum. Melbourne: Railway Technical Society of Australasia, 2016: 440–455.

Transport Sydney Trains. Celebrating 60 Years of Circular Quay Station 1956–2016. Sydney: Transport Sydney Trains, 2016. http://www.sydneytrains.info/about/heritage/160120-CircularQuay-posters.pdf.

Wolfers, H. 'The Big Stores between the Wars'. Twentieth Century Sydney: Studies in urban & social history, edited by Jill Roe. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1980.

Notes

[1] 'To the Editor', Sydney Morning Herald, 25 April 1857, 6; 'The Railway Terminus', Sydney Morning Herald, 3 December 1857, 3

[2] Gary McGregor and Bob Hammer, '100 years of metropolitan rail strategy in Sydney: lessons for the 21st Century', CORE 2016: Marinating the Momentum (Melbourne: Railways Technical Society of Australasia, 2016), 440–455

[3] GB Churchman, Railway Electrification in Australia and New Zealand (Sydney: IPL Books, 1995), 79

[4] R Gibbons, 'The "Fall of the Giant": trams versus trains and buses in Sydney, 1900–61', in G Wotherspoon (ed) Sydney's Transport: Studies in Urban History (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1983), 162

[5] Gary McGregor and Bob Hammer, '100 years of metropolitan rail strategy in Sydney: lessons for the 21st Century', CORE 2016: Marinating the Momentum (Melbourne: Railways Technical Society of Australasia, 2016), 440–455

[6] 'City Railway', Sydney Morning Herald, 16 November 1922, 8

[7] 'First Train', Sydney Morning Herald, 10 December 1926, 11

[8] 'City Railway: First Section opened', Sydney Morning Herald, 21 December 1926, 11

[9] M Ferson and Mary Nilsson (eds), Art Deco in Australia: Sunrise over the Pacific (Sydney: Craftsman House, 2001), 86

[10] SE Dornan and RG Henderson, The Electric Railways of New South Wales: A brief history of the electrified railway system operated by the New South Wales Government 1926 to 1976 (Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1976), 41

[11] Transport Sydney Trains, Celebrating 60 Years of Circular Quay Station 1956–2016, (Sydney: Transport Sydney Trains, 2016) http://www.sydneytrains.info/about/heritage/160120-CircularQuay-posters.pdf, viewed 10 November 2017

[12] M Ferson and Mary Nilsson (eds), Art Deco in Australia: Sunrise over the Pacific, (Sydney: Craftsman House, 2001), 86

[13] H Wolfers, 'The Big Stores between the Wars', in Jill Roe (ed), Twentieth Century Sydney: Studies in urban & social history (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1980), 31

[14] R Lee, Transport: An Australian History (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010), 218