The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Electrification of the Sydney Suburban Train Network

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

[media]By the turn of the twentieth century, Sydney’s train network was under increasing pressure from an expanding suburbia, growing patronage, slow trains and a central terminal that was isolated from the city centre that it served. To revitalise the network and meet the needs of the growing city the railway needed to be extended through the city; the central terminal had to be relocated; and the entire network electrified. This work was the single most significant event in the history of the Sydney rail system. It transformed the commuter experience and changed the face of the city.

First proposals

The first Central Station was near Redfern and rail commuters from the west and south had to transfer to trams or omnibuses for the final run into the Central Business District. As the city grew and more workers made their way into the centre, the system was coming under increasing pressure. This major urban planning problem was investigated via a series of Royal Commissions, parliamentary inquires and public works committees which each suggested various schemes. The only one to come to pass was the construction of a new Central Station, which opened its first stage in 1906. However trains still terminated outside the city boundary. In 1909, the Royal Commission on City Improvements recommended the construction of an underground railway loop through the city and an innovative plan to run a subway under Sydney Harbour to link the rail to North Sydney.[1]

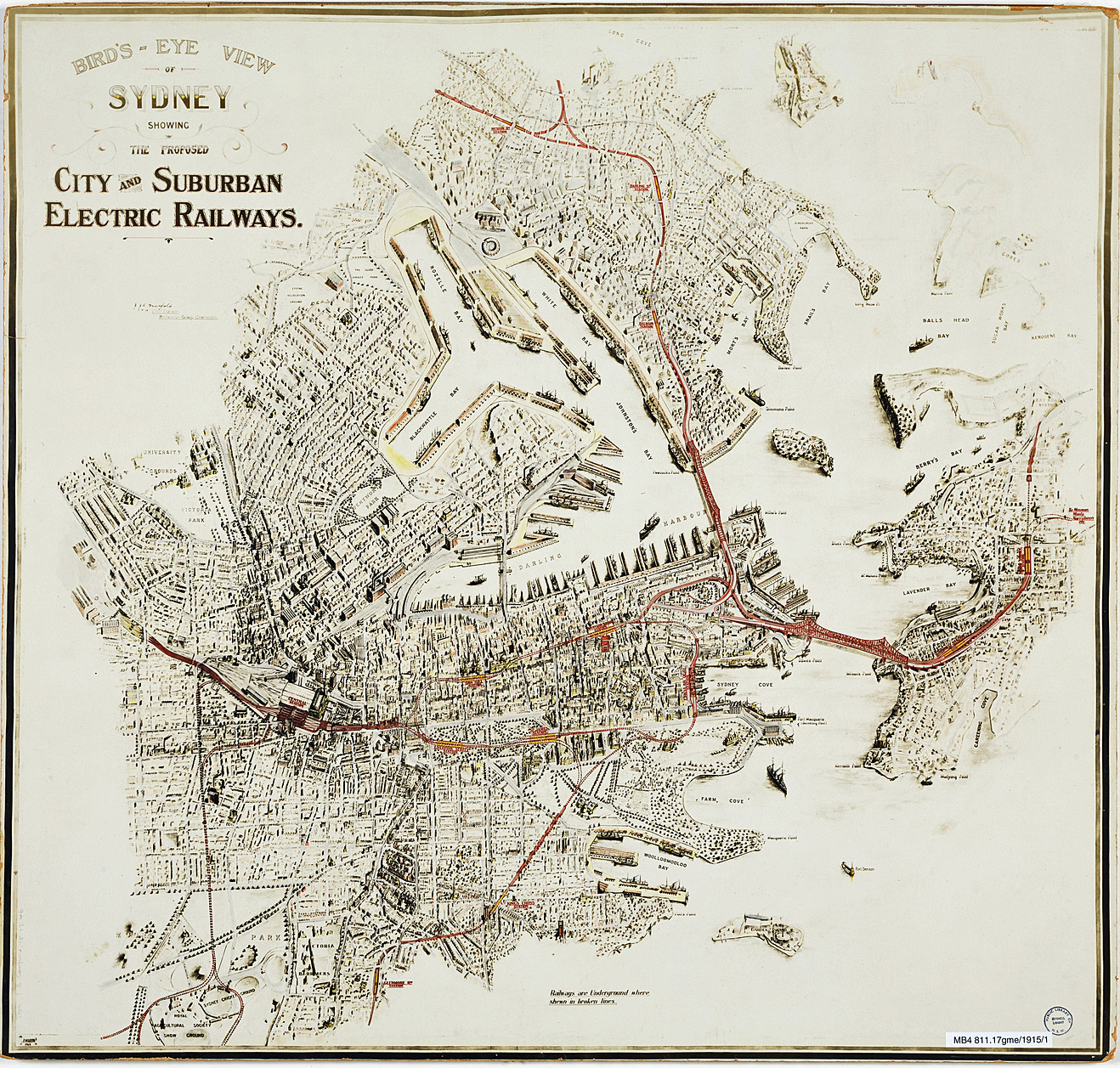

[media]In 1911, JJC Bradfield, an Engineer in the Department of Public Works, put forward a proposal to the Public Works Committee for an underground city loop, with a high-level bridge across the Harbour to carry trains to the north shore, and railway extensions to the northern beaches, eastern suburbs, the south, and west of Sydney. The committee adopted Bradfield’s plan and he was appointed Chief Engineer, Metropolitan Railway Construction before being sent on an overseas study tour to assess various international examples. Although Bradfield was able to convince the railway commissioners of his vision, the scheme suffered through opposition from conservative politicians representing rural interests, who saw any work on the city network as a waste of money.[2]

Bradfield’s vision

[media]Electrification of the network was central to Bradfield’s scheme. By 1911 Sydney’s electric trams were competing with older, heavier and more cumbersome steam trains in the inner city and suburbs. As Bradfield’s plan for an underground network was not compatible with a steam system, if the new underground was to be electric, the remaining system should be electrified at the same time. In 1915 Bradfield recommended a detailed overall plan for the network to the New South Wales Government.

Bradfield split the system into Inner and Outer Zones. The Inner would cover Sydney-Parramatta, Strathfield-Hornsby, Sydney-Sutherland, Sydenham-Bankstown and Milsons Point-Hornsby. The Outer Zone was Parramatta-Penrith, Blacktown-Richmond, Hornsby-Hawkesbury River, Granville-Campbelltown and Sutherland-Waterfall. Bradfield recommended immediate electrification of the Inner Zone and the construction of a double track loop underground through the city. In October 1915 the government passed the enabling legislation, the City Railway Act, although work was soon suspended under the pressures of World War I.[3]

The first lines

[media]Work on the underground loop recommenced in earnest in 1922. Bradfield had designed the system with overhead electric wires instead of an electrified third rail, as was used in some cities overseas. His decision was based on the power required to run the network; the safety of an overhead power supply, especially in large stabling yards with complicated track arrangements; and the relative ease of erecting the overhead catenary bridge-style masts to carry the wires. The White Bay Power Station, which supplied the tramways, would supply power to the network, along with a series of substations.

The first section of the underground, between Central and St James Station, opened on 9 December 1926 Although the underground was the most dramatic element of the new network and a potent symbol of the modernisation of Sydney’s transport system, it was not the first section electrified and the train to St James was not the first of the electrified cars.

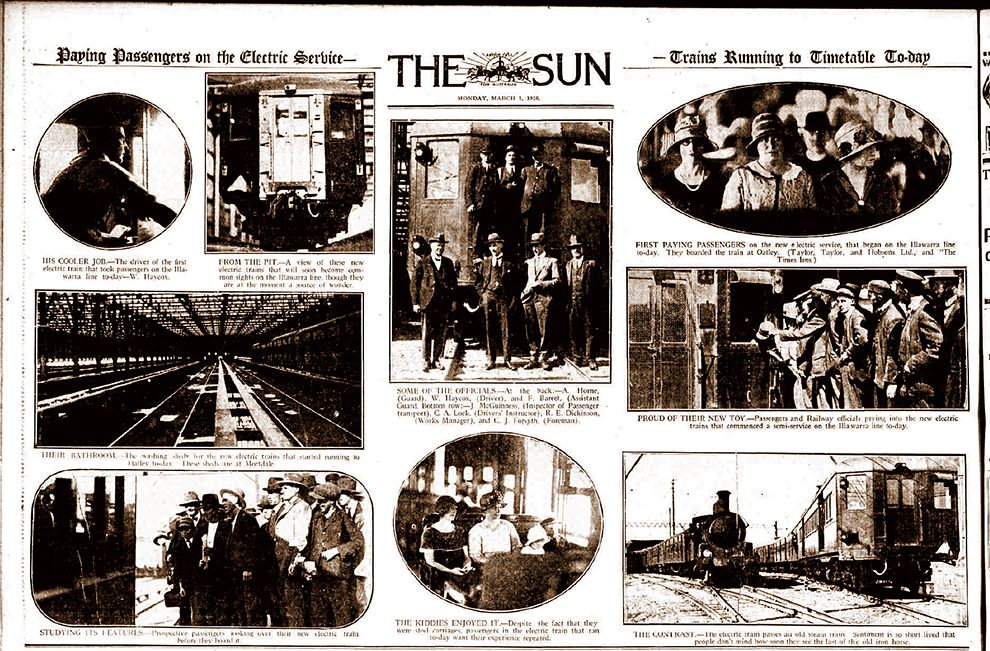

[media]Electric trains had been trialled, and crews trained, on a section of line between Tempe and Rockdale in June 1925. To prepare for the electrification to Illawarra, construction for overhead wiring was completed between Central and Oatley in 1926. The first train left Mortdale sidings at 7.10am, 1 March 1926, travelling empty to Hurstville where it took on passengers and went “all stations” between Hurstville and the city before returning to Oatley.[4] This first electric train represented a seismic shift in urban transport for Sydney, but newspaper reports suggest that commuters hardly noticed. The Sydney Morning Herald reported that:

When an opportunity to travel for the first time in an electric train was presented, it might be expected that people would exploit the sensation immediately, avidly, enthusiastically. On the contrary, they did not show the least preference for the new train, and those who did ride in it bore the experience as though it were one of everyday unimportance.[5]

Although this represented the start of the modernisation of the network, the potential offered by electric trains in terms of increased speed and longer trains, was yet to be realised. The first electric trains operated to a slower timetable within the steam network. The first accelerated timetable was introduced between Sydney and Sutherland on 5 September 1926 as steam trains were removed and entirely replaced with electric trains. The new service cut commuting times for travellers and allowed trains to run every ten minutes rather than every twenty as they had under steam. The Railway Department had to discourage travellers from, jumping aboard the faster moving trains as was common with steam.[6]

[media]The electrification of the network did not just mean changing over trains and erecting overhead wiring, but also constructing whole new stations to accommodate them. To build the section of the underground loop to St James and the excavated Museum and St James Stations, over half of Hyde Park was torn up. Central Station, as the main terminal, was transformed from an end of the line terminus to a through station for the city, the northern and proposed eastern suburbs lines. Work at Central included the construction of a complicated series of lines to the south, eight new platforms along the eastern side to take the suburban trains, as well as works to overhead bridges to accommodate wider track areas.

The most complicated work was the Flying Junctions, a series of flyover tracks between the Cleveland Street bridge at Redfern and Central that allowed trains to move from any one line to another without crossing a line in the opposing direction.[7] They were the largest construction of their type in the world.[8]

Bradfield’s plan also called for new steel train bodies to replace the timber bodies of the older trains; a new dedicated workshop at Chullora; as well as track widening; quadruplication of lines, power supply, substations and new electric signaling. It was a complete overhaul of the railway in Sydney.

The inner zone

As work continued on the underground city circle, suburban lines were converted to electric trains. The trial line to Oatley was followed by the Bankstown line, and electric running started between Sydney and Bankstown on 24 October 1926. The line was powered by a substation at Belmore.

North of the harbour, while the Harbour Bridge was under construction, a temporary station was built at Lavender Bay to replace the old Milsons Point station, which had been demolished to make way for the northern pylons of the bridge. This section of line was converted to electric running from September 1927, although a second train was not added until November. As the northern line was isolated from the other lines, and Strathfield to Hornsby was still under steam, electric cars had to be hauled to Hornsby by steam locomotives before they could run along the line. On 16 July 1928 steam trains were withdrawn from the North Shore line and a complete electric service began. As with the other lines, travel times were cut by as much as ten minutes each way. The power and acceleration of electric trains was demonstrated on the steep gradients of the line on the North Shore. The next month the line between Central and Homebush went electric and in October the Central to Ashfield and Ashfield to Homebush sections followed.

Between January 1929 and 9 June 1929, the line between Central and Hornsby via Strathfield was converted to full running. This section had originally been designated as the last section, but was brought forward due to the steam haulage of electric cars to Hornsby to operate on the North Shore line.[9] The line between Granville and Liverpool, which then served a sparsely populated region, went electric in early 1930. At the same time a new line was constructed as part of the suburban network between a junction at Wolli Creek and East Hills in the southwest. The first trains began running on this to Kingsgrove in September 1931 and were extended to East Hills in 1939.

[media]All the while, work on the underground city line continued, with the main section between Central, Town Hall and Wynyard completed in late 1931. It opened to the public on 28 February 1932, just three weeks before the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The Bridge opening on 19 March was also the day the first train carried passengers across. A special train left Wynyard at 12.30pm with official guests and 600 passengers for North Sydney and returned to Wynyard. Regular passenger services began the following day.[10]

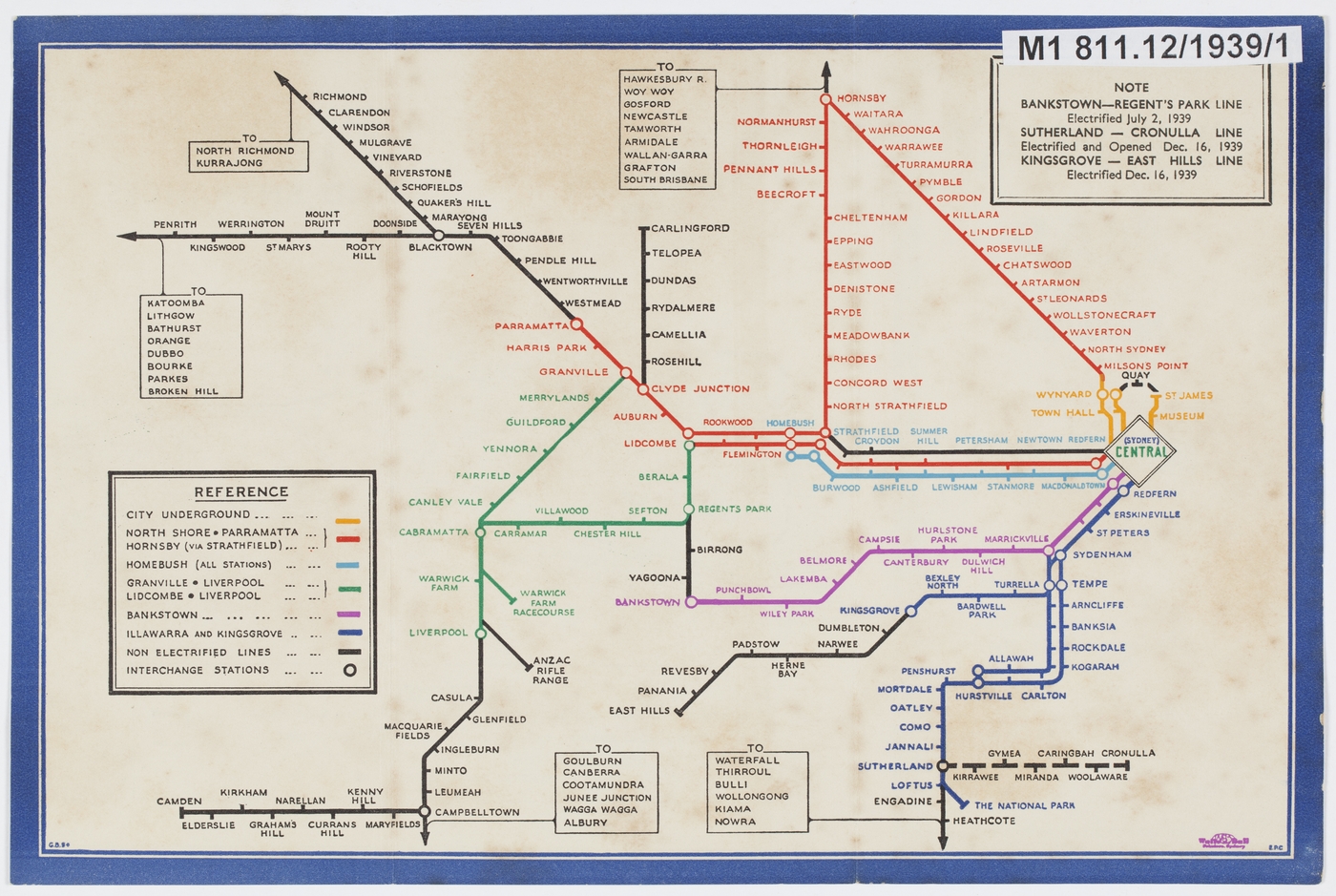

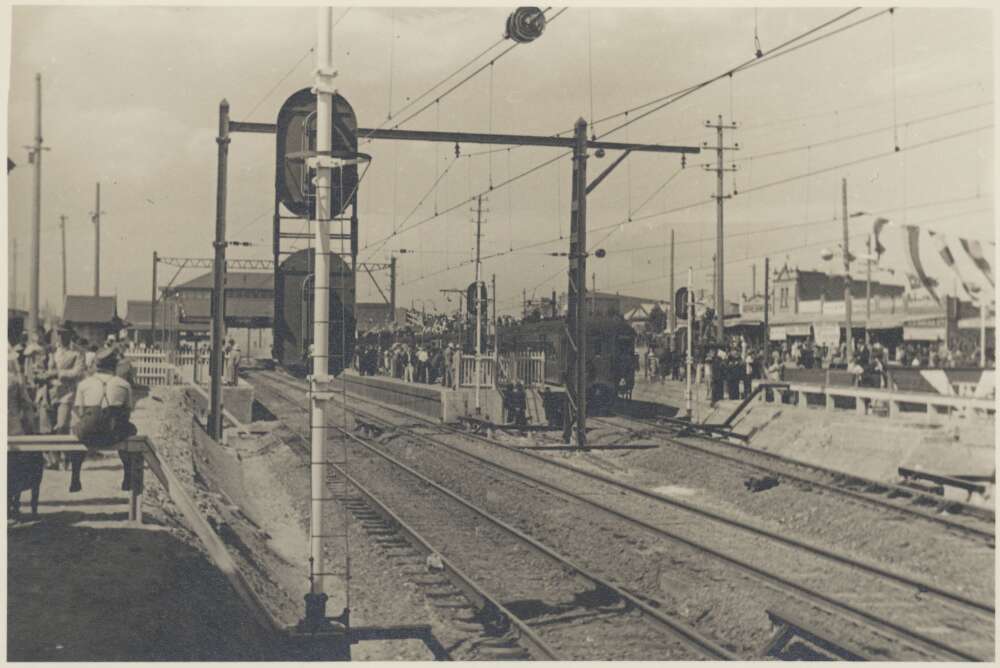

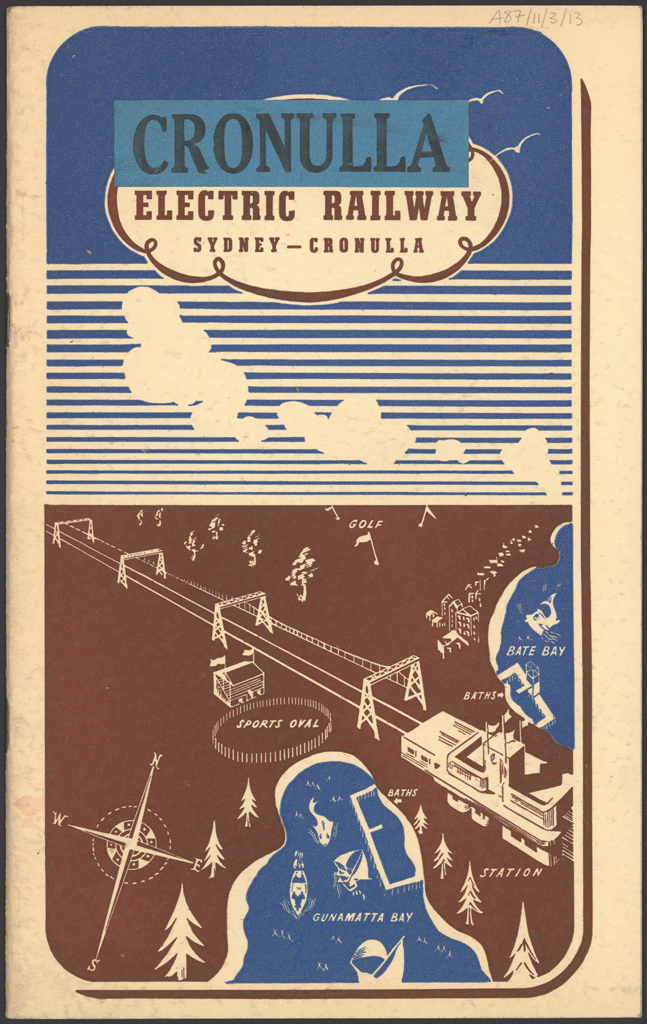

[media]The opening of the Harbour Bridge and the linking of the city to the northern line signalled the effective completion of the electrification of Bradfield’s inner zone network, except for the linking station of the city circle at Circular Quay, which would not be opened until 1956. The remainder of works consisted of smaller sections between Clyde-Rosehill (1936) and Sefton-Elcar, Bankstown-Sefton, Sutherland-Cronulla and Kingsgrove-East Hills, all completed before another war in 1939.[11]

The outer zone

[media]The electrification of the inner zone and the construction of the Harbour Bridge and the city underground had a profound effect on the numbers of commuters using the rail network and stimulated a revival of the city’s CBD and shopping precinct. Passenger numbers rose from 117.6 million in 1925 to 137.5 million by 1930.[12] However, the electrification of the remainder of the system was again delayed as the Great Depression led into World War II.

When the electrification program resumed in 1954, the focus shifted to the western lines of the network. The first section was the Lidcombe Triangle, where the western and southern lines branched, which was completed in 1945, followed by Parramatta-Penrith in 1955 and then, in sections, over the Blue Mountains to Lithgow by 1957.

The advantages of the electrified system were appreciated in the outer districts of the city, where travel times were longer and services less frequent under steam. In contrast to the nonchalance of the commuters who boarded the first electric train at Hurstville in 1926, Penrith welcomed the first electric train with a festival, with ribbon-cutting at Doonside, Rooty Hill, Mount Druitt, St Marys and Penrith stations, as the official train passed through. At Penrith Showground there was a street parade of fifty floats, street dancing and marching bands and a full carnival program.[13]

Work continued throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s as smaller suburban lines were converted and the inter-city lines were prepared for electrification. These included Hornsby-Cowan (1958), Rosehill-Carlingford and Camellia-Sandown (1959) and the Enfield Marshalling Yards. Liverpool-Campbelltown was completed in 1968, Blacktown-Riverstone in 1975, as well as the goods lines from Canterbury to Rozelle and Flemington to Homebush.

The last of the major works was carried out in the 1980s, when the outer lines between Loftus and Waterfall and the extension to Helensburgh were finished, in 1980 and 1984 respectively. The 1991 Riverstone to Richmond electrification completed the conversion of the city suburban network that had started 68 years before.

References

Australian Railway Historical Society. ‘Sydney’s Railways’, in Fraser D. (ed) Sydney: From Settlement to City-An Engineering History of Sydney. Sydney: Engineers Australia Pty Limited, 1989.

Churchman, GB. Railway Electrification in Australia and New Zealand. Sydney: IPL Books, 1995.

Dornan, SE & Henderson RG, The Electric Railways of New South Wales: A Brief history of the Electrified Railway System operated by the New South Wales Government 1926 to 1976. Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1976.

Lee R. Transport: An Australian History. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010.

[1] GB Churchman, Railway Electrification in Australia and New Zealand (Sydney: IPL Books, 1995), 79

[2] R Lee, Transport: An Australian History (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010), 216

[3] Australian Railway Historical Society (ARHS), ‘Sydney’s Railways’, in D Fraser. (ed) Sydney: From Settlement to City-An Engineering History of Sydney (Sydney: Engineers Australia Pty Limited, 1989), 86

[4] SE Dornan & RG Henderson, The Electric Railways of New South Wales: A Brief history of the Electrified Railway System operated by the New South Wales Government 1926 to 1976 (Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1976), 22

[5] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 March 1926, 9

[6] SE Dornan & RG Henderson, The Electric Railways of New South Wales: A Brief history of the Electrified Railway System operated by the New South Wales Government 1926 to 1976 (Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1976), 22

[7] R Lee, Transport: An Australian History (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010), 217

[8] SE Dornan & RG Henderson, The Electric Railways of New South Wales: A Brief history of the Electrified Railway System operated by the New South Wales Government 1926 to 1976 (Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1976), 24

[9] SE Dornan & RG Henderson, The Electric Railways of New South Wales: A Brief history of the Electrified Railway System operated by the New South Wales Government 1926 to 1976 (Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1976), 34

[10] SE Dornan & RG Henderson, The Electric Railways of New South Wales: A Brief history of the Electrified Railway System operated by the New South Wales Government 1926 to 1976 (Sydney: Australian Electric Traction Association, 1976), 41

[11] Australian Railway Historical Society (ARHS), ‘Sydney’s Railways’, in D Fraser. (ed) Sydney: From Settlement to City-An Engineering History of Sydney (Sydney: Engineers Australia Pty Limited, 1989), 88

[12] R Lee, Transport: An Australian History (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010), 220

[13] Nepean Times, 6 October 1955, 1