The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Death and dying in nineteenth century Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Death and Dying in nineteenth century Sydney

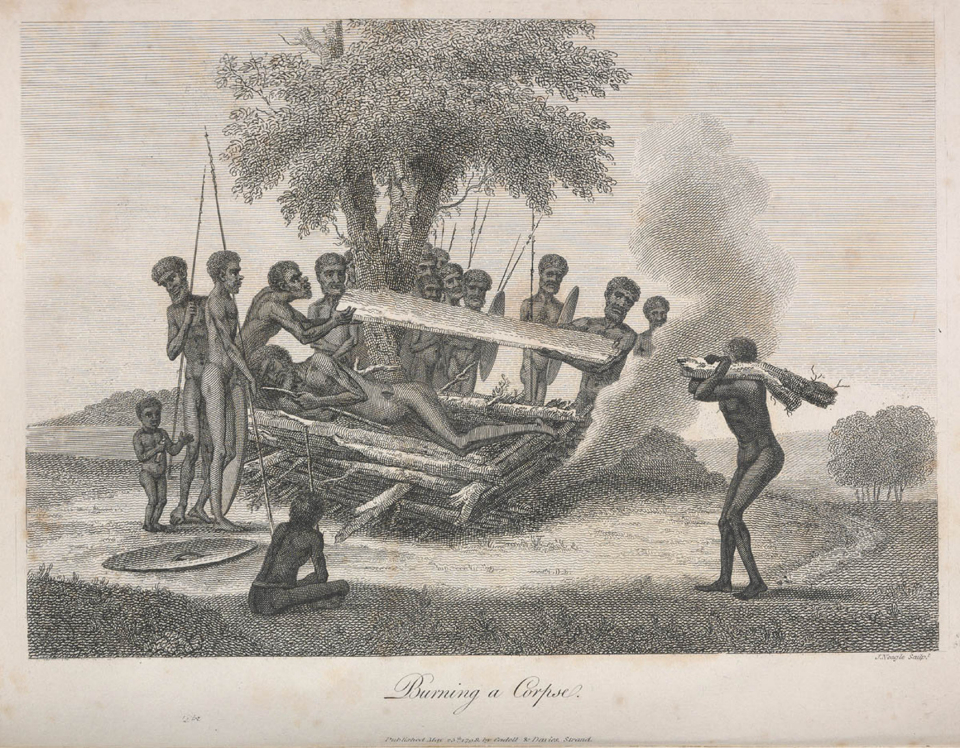

Aboriginal death rituals

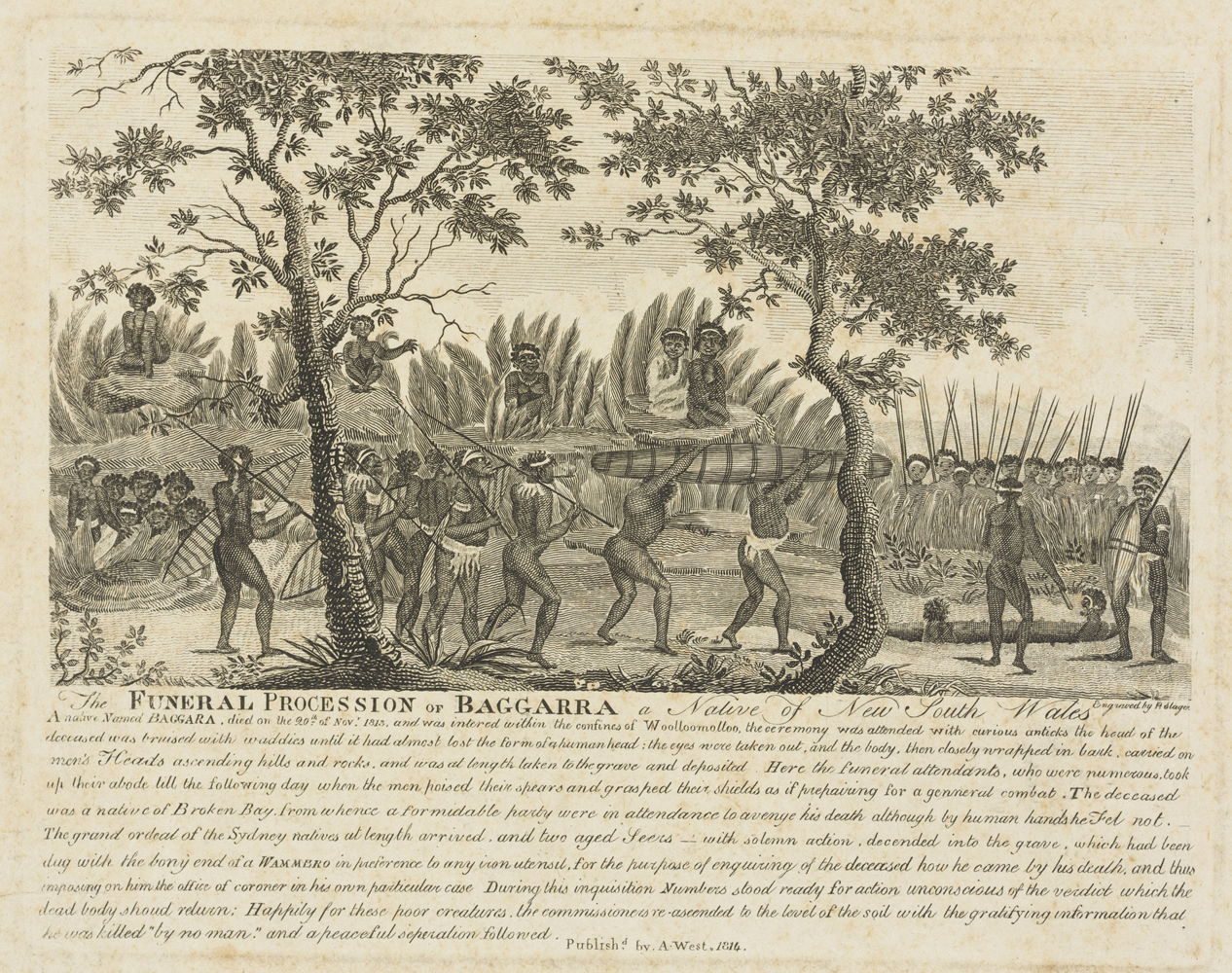

[media]Death, funerals and burials were important to the belief system of Aboriginal people. In the Sydney region, there were two main ways of disposing of the dead: burial, or cremation followed by burial. Observations by David Collins suggest that the method of disposal was indicative of the deceased's age or status, with cremation being accorded to people beyond middle age. Burial took place around estuaries or along the coastline and often occurred in shell middens. Carved trees were often associated with burials in south-Eastern Australia; there are some sites recorded in the late nineteenth century around Picton and Narellan but no descriptions survive from early colonists. Rituals were associated with the preparation of the corpse and goods were sometimes buried with the deceased.[media]

[media]Traditional Aboriginal burial practices continued in the outer regions of Sydney basin much later than around Port Jackson. Aboriginal people who frequented Sydney town were sometimes buried according to British customs on estates or in burial grounds. Arabanoo (died 1789) and Ballederry (died 1791) were buried in the grounds of first Government House; Bennelong (died 1813) and Nanbaree (died 1821) were buried on the estate of James Squire at Kissing Point; Bungaree (died 1830) was buried at Rose Bay; and Cora Gooseberry (died 1852) was buried in Devonshire Street Cemetery. [1]

First colonial burial grounds

The first burials in the colony were utilitarian and practical. The fledgling township, struggling against the alien climate and conditions, could do little but dispose of the remains. Nothing survives of the first series of informal burial grounds established around the Rocks. What little we do know is gleaned from incidental descriptions in official documents and letters.

Little is known about the burials during the first five years of the colony. What we do know is due to the extensive research undertaken by Keith Johnson. From early correspondence and diary entries it seems the first informal burial grounds were located close to the infant township. It is hard to reconcile the different descriptions. There are references to one at Dawes Point for mariners and seamen, another within the Rocks, possibly somewhere within the block today bounded by Essex, Gloucester, Grosvenor and Harrington streets, and a third behind the military barracks at Clarence Street. [2]

[media]The first cemetery to be officially set apart for the township of Sydney was the Old Sydney Burial Ground. It was established in late 1792 on the main road (George Street) on the outskirts of the settlement. Extended in 1812, the cemetery was closed in January 1820 as it was full. The site remained dormant and neglected as the city grew around it until 1869 when the land was granted to the Sydney Municipal Council for the site of the town hall.

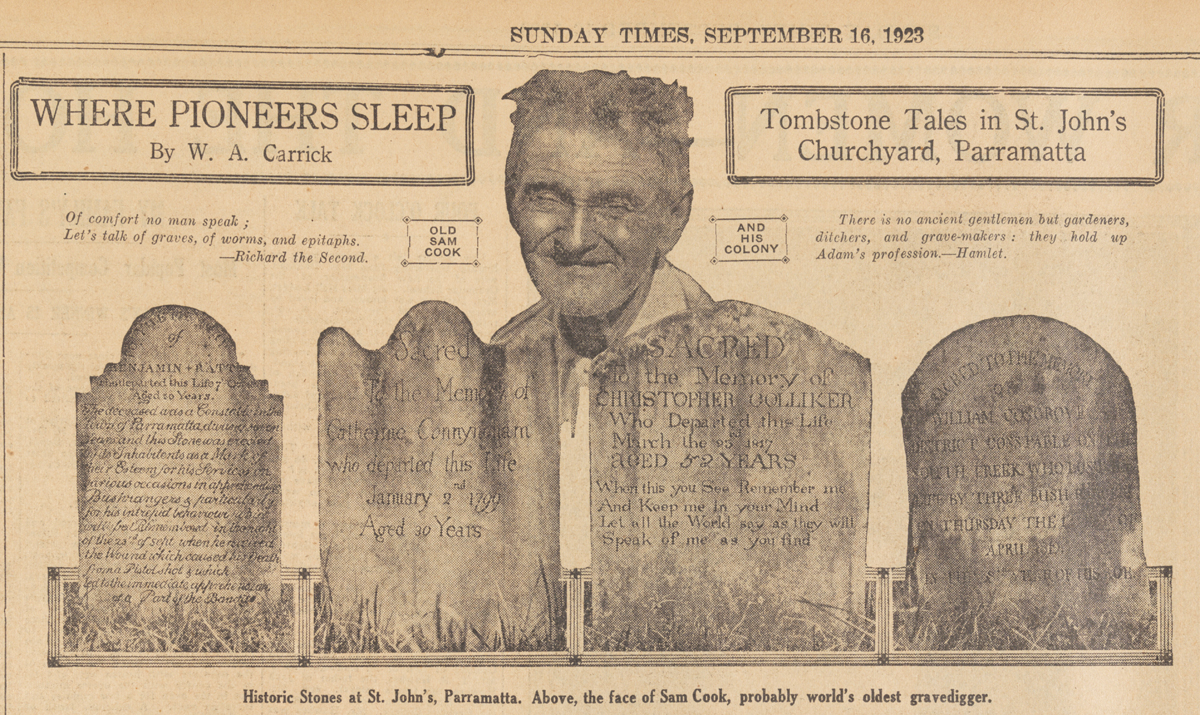

[media]The settlement of Parramatta had its own series of burial grounds as the distance between the settlements was too vast to just have a single colonial cemetery. St John's Church of England Cemetery was established in 1790 and buried all denominations until other cemeteries were established. The Catholic Church gained St Patrick's Cemetery in 1822. St John's Cemetery, Parramatta, [media]remains the earliest undisturbed colonial cemetery in Sydney with headstones dating back to [media]1791.

When the colony was established in 1788, life expectancy was only around the thirties. Infectious diseases or accidental deaths were the main causes of death. Infant mortality rates were high. [3] By the 1850s, life expectancy was still below 50 and infant mortality rates were around 140 deaths per 1,000 live births. [4] It was not until 1856 that a thorough civil system for the registration of births, deaths and marriages was introduced. Statistics prior to this date rely heavily upon church registers which vary in their information and reliability. The absence of a clergyman left gaps in the records.

Funeral customs

Funerary customs from the mother country were readily incorporated into the daily lives of the colonists. Francois Peron, visiting Sydney in 1802 as part of the French expedition under Nicolas Baudin, recorded in his notebook that the public burial ground (the Old Sydney Burial Ground) was remarkable for a number of striking monuments, 'the execution of which is much better than could reasonably have been expected from the state of the arts in so young a colony'. [5] Cabinet makers doubled as undertakers, preparing coffins made out of cedar and other local timbers. Thomas Shaughnessy was amongst the early undertakers to advertise the two branches of his business. Alongside the 'various assortment' of wardrobes, chests of drawers, and 'elegant side boards', he offered 'Funerals Furnished and conducted with greatest attention, from the plainest to the most sumptuous exhibition of mourning grandeur, and with a consistent regard to economy, without diminishing the necessary respectability'. [6] Already in 1826 there is a link between mourning grandeur and respectability.

Funeral processions

Funeral processions of prominent colonists were recorded in the Sydney Gazette as a sign of respect and, no doubt, a documenting of spectacle. The first use of mutes as part of the funeral procession in 1811 was a remarkable occasion. The Sydney Gazette recorded upwards of 200 mourners attended the funeral of Catherine Connell, wife of Mr John Connell of Pitt Street, in spite of the 'wetness of the afternoon'. Not only was the procession noteworthy for the use of 'Two Mutes, bearing staves (the first occasion of such being introduced in this Colony)'; it formed 'one of the most numerous and respectable that in this Territory ever attended a departed Sister to the Grave'. [7] Wakes were also part of the death ways, but differed according to ethnicity. Grace Karskens notes the English tended to gather for eating and drinking after the funeral, whereas the Irish gathered in the home around the laid out corpse, 'talking, eating, singing, getting drunk' and the conviviality continued after the funeral. [8]

The funeral of the merchant Thomas Burdekin in 1844 gives us a glimpse of a wealthy funeral in Sydney in 1844. The funeral service was held at St James Church. The undertaker, William Beaver, dressed the corpse in a 'superfine shroud and cap'. A strong cedar coffin was placed inside 'a State Coffin covered with velvet and richly mounted with Gilt furniture with an engraved brass plate'. The hearse was drawn by four horses draped with black velvet and with plumes of ostrich feathers on their heads. There were at least six mutes and porters. The mourning party was supplied with hatbands, gloves and scarves. This extravagant funeral came to £61 4s. [9]

The increasing demands for the chaplain's services led to conflicting engagements. Some mourners wished to process from the church to the cemetery, at the same time as other interments were to take place in the cemetery. So, in 1820, it was decreed that the hour of interment during the winter months would be 4 pm and, for climatic reasons, 5 pm during the summer season. [10] The chaplain was paid 5 shillings for burying free citizens and performing the funeral service. Attendance by the parish clerk attracted another fee of 2s.6d.. The tolling of the church bell could be had for sixpence. [11]

Township cemeteries

[media]The model for burial grounds which was imported from Britain as part of the colonists' cultural baggage was the parish church and churchyard. The early burial grounds of Sydney were small and generally catered for one denomination only. Initially this was the Church of England but by the 1810s the government was starting to recognise the need to cater for other denominations. The reading of the burial service was also officially monopolised by the Church of England clergy, there being no other official representatives until 1819, when Catholic priests Fr John Therry and Fr Philip Conolly arrive in Sydney. Presbyterians weren't assigned their own minister until 1822 with the arrival of the Revd John Dunmore Lang, however, they began their own little community out at Ebenezer in 1807, building a church and burial ground.

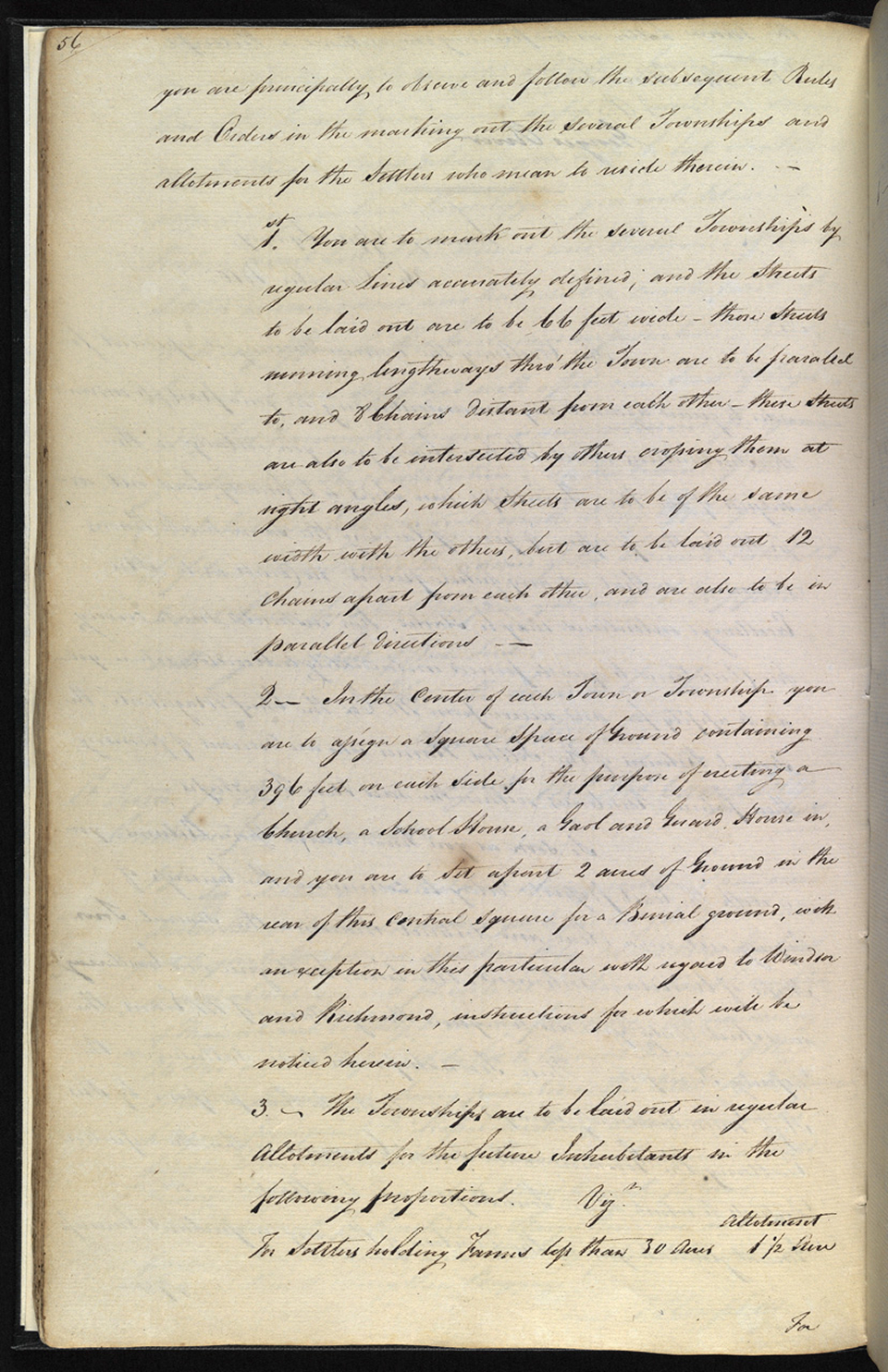

[media]Amongst the first cemeteries to be formally established and consecrated were the six burial grounds proclaimed by Governor Macquarie in 1811 at Liverpool, Windsor, Richmond, Pitt Town, Castlereagh and Wilberforce. These were essentially Church of England burial grounds. Their locations – and indeed each of the towns' locations – were carefully selected by Macquarie; on a ridge, with panoramic views of the Hawkesbury floodplains and Blue Mountains in the distance, typifying the beautiful location for a parish church and churchyard, soon to be endorsed as a cemetery ideal. Their elevated position allowed them to be seen from all the surrounding country and they became a solemn visual reminder of religion and mortality.

When Governor Macquarie declared the township cemeteries open in 1811, he also directed that private burials on farms should cease and that all settlers :

shall in a decent and becoming Manner inter them in the consecrated Grounds now assigned for that purpose in their respective Townships. [12]

Nevertheless, burial on private property remained the most efficient way to dispose of the dead in isolated rural areas where colonial government administration was rarely felt and where religious communities were small or non-existent. He also issued the first orders to regulate cemeteries and burial practices. Graves had to be a suitable depth for decency's sake and so as not to cause any offence or annoyance. The cemetery had to be 'speedily enclosed' by a 'good wall or strong palisade'.

The practice of locating burial grounds outside township boundaries was desirable from a sanitary viewpoint. It also conformed to the latest thinking of the burial reform movement in Europe and Britain. In 1825 the practice of extramural burial grounds was formalised, with legislation ruling that no burials could take place within the walls of a church (a common practice amongst the wealthy in Britain during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) and that all burial grounds should be located at least one mile outside the town. [13] This was a progressive stance for the new colony to adopt. [14]

Sectarianism and the separation between Church and State

As communities were established and grew in the colony, religious authorities could apply to the government for a grant of land, either as an individual grant for a burial ground or as part of church lands, which also incorporated a church and often a school. The customary area for the appropriation of church land up until the 1850s was three acres (1.2 hectares): 1 acre for a church, 1 acre for a burial ground, ½ an acre for a school and a ½ acre for a parsonage. While some churchyards were placed around the church, it was more common in government land grants for a distinct and separate area to be surveyed for a burial ground. The church and churchyard were often placed adjacent to one another. However, sometimes there was some distance between the church and cemetery, with sightlines and views establishing the relationship between the two.

The government provided the land for burial grounds but handed over the management of burials and the actual sites to the clergy. This set a precedent, which would shape the future design and management of cemeteries in the colony. It was all part of move by the colonial government to establish a distinction between the Church and the State. The introduction of The Church Act 1836 ensured that all religious denominations could administer their own burial grounds, sounding the death knell of the Church of England monopoly over the burial of the colonists. The clergy of the Churches became protective about their right to consecrate burial grounds, charge fees for burial and control the land.

[media]By the 1840s, it was common practice for the government surveyor-general to group denominational burial grounds together, separated from the churches, on the outskirts of the town. This grouping of burial grounds foreshadowed the future design of general cemeteries. The burial grounds at Elizabeth and Devonshire streets are an early example of this grouping of burial grounds outside the township. The Devonshire Street Cemetery (as it is most commonly known) was established near the brickfields on the outskirts of Sydney (where Central Railway Station is now located). The first burial ground opened in 1820, replacing the Old Sydney Burial Ground on George Street, and was set aside for Church of England burials only. Subsequently, other denominations were allotted adjacent land for burial grounds upon application to the colonial government. By 1836, there were seven burial grounds on the site, covering a total of 11 acres (4.5 hectares), 3 roods (.3 hecares) and 11 ½ perches (approximately 61 metres). The layout of Devonshire Street Cemetery was an ad hoc arrangement, responding to the needs of the different religious communities for burial space. In this sense Devonshire Street Cemetery was not a general cemetery, but seven distinct denominational cemeteries. Each denomination managed its own burial ground, which was fenced, had an exclusive entrance, and its own scale of fees and charges.

[media]With the main cemetery for the Sydney populace (Devonshire Street Cemetery) literally overflowing, the government finally decided in 1845 to create a new burial ground for the citizens of Sydney. The General Cemetery Bill sought to radically alter the role of the various religious denominations in the management of cemeteries. Under the Bill, cemeteries were to become interdenominational, with common burial space, rather than separate areas for each denomination. It was also proposed that a central body of lay trustees manage the cemetery and set fees for burial, rather than each denominational group having its own trustees for its own area. Worthy as these aims were in establishing a truly secular and practical approach to the burial of the dead in Sydney, it found little support. Sectarianism led to widespread objections and the concept was watered down. The churches won the right to have their own denominational portions within the area dedicated as general cemetery for the whole population.

The General Cemetery Act was finally passed in 1847 and it seemed like Sydney would get its new cemetery. Various sites were proposed, at Grose Farm, Garden Island, the Domain, and Blackwattle Swamp. But all were rejected because of their distance from the city, inadequate size, unsuitable soil composition and the potential for water table contamination. The government finally settled upon the Sydney Common (Moore Park) and set aside 23 acres (9.3 hectares). But the inappropriate site, church opposition and government inaction meant the cemetery was never formally consecrated and used. Sand drifts reclaimed the site. It was another 20 years before a large general cemetery – the Necropolis at Haslem's Creek (now Rookwood Necropolis) – was provided to bury all the citizens of Sydney. In the meantime, the smaller denominational groups, such as the Wesleyans and the Independents, struggled to bury their dead.

By 1859 the design of general cemeteries had been standardised by the NSW Surveyor General's office: eight acres (3.2 hectares) to be divided into separate areas for the six main religious denominations (Church of England, Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, Wesleyan, Independent and Jewish) proportionate to their representation in the 1856 census figures. A seventh, generic area (known confusingly as a general area) was set aside to bury all other denominations. The standard general cemetery design with a central avenue and seven allotments based on religion was applied to nearly all general cemeteries surveyed in NSW in the late nineteenth century. [15]

Overcrowded cemeteries

[media]The Church of England was frustrated by the government's attempts to control the burial of the dead and cemetery management through the 1847 General Cemetery Act. In protest they set up their own cemetery at Camperdown. It was set up with funds from a joint-stock company, known as the Sydney Church of England Cemetery Company. The company purchased just over 12 acres (4.9 hectares) of land for the exclusive burial of Church of England parishioners. The Camperdown Cemetery was one of only two company cemeteries established in nineteenth century Sydney. The other was Balmain Cemetery, a totally different proposition. Camperdown Cemetery is often referred to as St Stephen's Cemetery or Churchyard, because St Stephen's Church is located within the cemetery grounds. But the church was built later, in the early 1870s, after the cemetery was closed to new burials.

Between 1845 and 1867 Sydneysiders struggled to bury their dead. There were not enough cemeteries to deal with the growing population. A number of scandals led to two parliamentary inquiries into the state of Sydney's cemeteries and management in 1855 and 1866. [16] The spotlight turned on Sydney's older cemeteries near the city centre: Devonshire Street Cemetery, Camperdown Cemetery and the cemeteries at Randwick. The evidence recorded from dozens of witnesses, along with the public debate that ensued both in the newspapers and parliament, provides a glimpse of common perceptions held about death, burial and cemeteries in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Overcrowded cemeteries were condemned as 'revolting to the good feelings, and injurious to the health of the inhabitants'. [17] The public recoiled at images of jam-packed cemeteries, with coffins breaking the surface and emanating effluvia. Complaints centred around 'unpleasant', 'offensive' and 'noxious' smells that were said to be at their worst in Sydney's hot humid summer weather and after rain. Pauper graves which were left open for several days to receive numerous bodies attracted 'nasty greenish-blue' blowflies. The disgorging of maggots after heavy rain was a stark reminder of the underworld of corruption – an image which contrasted dramatically with the idealisation of the cemetery as 'God's acre' and religious beliefs in a physical resurrection.

These inquiries highlighted public health concerns but did little to actually address the problem of cemetery conditions and so the spectre of unsanitary burial practices in cemetery continued to arise in the late nineteenth century. What they revealed was the Victorian religious sensibility towards the treatment of the corpse and the desire of the general population for a 'respectable' funeral and a 'decent' burial.

Pauper burials and respectable funerals

In the newly settled colony, the cemetery became an important cultural institution in which the social order could be established and a person's identity with the community could be defined. Statements of status, class and religion were constructed through the trappings of the funeral and were inscribed upon the cemetery landscape.

A 'decent' burial usually meant a funeral with a hearse and at least one mourning coach, a coffin made of cedar or covered with cloth and burial within a select grave on which the family could erect a headstone. The wealthy aspired to long funeral processions with multiple carriages and a brick-lined vault in a select area of the cemetery where a large monument or mausoleum could be erected.

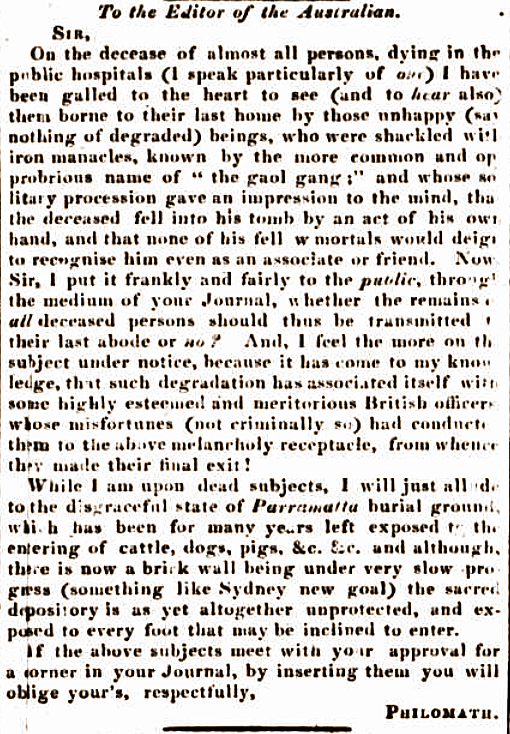

A respectable funeral was a sign of social status, but it also provided some protection to the corpse and ensured the sanctity of the grave. A pauper burial could provide no such guarantee. Many citizens buried relatives beyond their financial means in order to obtain a respectable burial.

A simple pine wood board coffin, light in colour, was the distinguishing mark of a pauper burial in Sydney. Often there wasn't even a nameplate on the coffin and in such instances, in order to distinguish between Protestant and Roman Catholic paupers, a cross would be drawn on the coffin of a Catholic. Pauper and common graves were located in the least desirable areas of cemeteries, away from major pathways on low lying, poorly drained land. They were segregated geographically, and visually, from the select areas of private graves chosen by the 'respectable portion of the community'. Pauper or common graves usually had more than one coffin in each grave. Frequently, a coffin would be left virtually uncovered with just a scattering of earth while the grave waited for more burials and it was not unheard of for up to four corpses to be placed in one grave. This practice was referred to as the 'packing system', where coffins were literally piled on top of one another. Shallow burials were a common occurrence, even if such actions were not condoned in health and cemetery regulations. There were regular reports of coffins being only a few inches below the surface and easily uncovered, touched or penetrated by a foot, an umbrella or walking stick.

[media]A common or pauper burial was reviled by the middle and labouring classes, a fate to be avoided at all costs. It was a mark of social disgrace. There was no guarantee that a common or pauper grave would not be disturbed. The anonymity of such graves, where no monuments were allowed, discouraged the veneration of the dead. The regulations and charges of cemeteries denied the poorer classes the opportunity to participate in the collective social ritual of mourning.

[media]Cemetery monuments were an integral part of the commemorative landscape. The erection of a gravemarker gave surviving relatives, friends and the general public the opportunity to construct a private memory of, as well as a social identity for, the deceased. Headstones and inscriptions were clear statements of religious affiliation and social identity. Chosen, and occasionally even composed, by mourners, verse epitaphs provide important evidence of the hopes, beliefs and desires of mourners. The virtues and religious convictions of the deceased were usually extolled. Such epitaphs functioned as a reminder to the living to keep their faith. Collectively, the grave and the cemetery landscape encouraged mourning, remembrance, consolation and faith.

Rookwood Necropolis

The Necropolis at Haslem's Creek (now known as Rookwood Necropolis) opened in 1867 and was the elaborate and triumphant exemplar of the cemetery ideal in Sydney. The government set aside an enormous quantity of land – 200 acres (81 hectares) – so that the Necropolis would avoid the problems of overcrowding encountered by earlier cemeteries thereby ensuring it would serve as Sydney's main cemetery for many years to come.

[media]It was located outside the metropolis and was linked to the city by train, providing an economic – and decorous – way for funerals to proceed to the cemetery. The landscape design of the original 200 acres of the Necropolis was highly ornamental in the gardenesque style, with separate denominational areas. The landform and layout were picturesque and romantic, beautified with specimen trees and winding walks. Now covering 283 hectares and still in use, the Necropolis is Australia's largest cemetery and is amongst the largest Victorian era burial grounds in the world.

References

Pat Jalland, Australian Ways of Death: A Social and Cultural History 1840–1918, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2002

Pat Jalland, Changing Ways of Death in Twentieth Century Australia: War, Medicine and the Funeral Business, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2006

Allan Kellehear (ed), Death & Dying in Australia, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2000

Allan Kellehear, A Social History of Dying, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007

Keith A Johnson & Malcolm R Sainty, Sydney Burial Ground 1819–1901: Elizabeth and Devonshire Streets and History of Sydney's Early Cemeteries from 1788, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 2001

Lisa Murray, 'Cemeteries in Nineteenth Century New South Wales: Landscapes of Memory and Identity', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2001

Robert Nicol, This Grave and Burning Question: A Centenary History of Cremation in Australia, Adelaide Cemeteries Authority, Adelaide, 2003

Notes

[1] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records, second edition, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 139–142; Keith A Johnson and Malcolm R Sainty, Sydney Burial Ground 1819–1901: Elizabeth and Devonshire Streets and History of Sydney's Early Cemeteries from 1788, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 2001, p 205

[2] For example, see Keith Johnson, 'Sydney's Earliest Burial Grounds – Part 1', Descent, vol 4, no 3, 1969; Keith Johnson, 'The Historical Grave', 10,000 Years of Sydney Life, edited by Peter Stanbury, The Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, 1979, pp 11–19; Keith A Johnson and Malcolm R Sainty, Sydney Burial Ground 1819–1901: Elizabeth and Devonshire Streets and History of Sydney's Early Cemeteries from 1788, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 2001

[3] Allan Kellehear, 'The Australian Way of Death: Formative Historical and Social nfluences' in Allan Kellehear (ed), Death & Dying in Australia, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2000, p 10

[4] Peter McDonald, Lado Ruzicka and Patricia Pyne, 'Marriage, Fertility and Mortality' in Wray Vamplew (ed), Australians: Historical Statistics, Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates, Broadway, 1987, p 42

[5] Francois Peron, A Voyage of Discovery to the Southern Hemisphere, translated from the French, Richard Phillips, London, 1809, p 276

[6] The Sydney Monitor, 26 May 1826

[7] Sydney Gazette, 25 May 1811

[8] Grace Karskens, 'Death Was in his Face: Dying, Burial and Remembrance in Early Sydney', Labour History, no 74, May 1998, pp 27, 29

[9] Pat Jalland, Australian Ways of Death: A Social and Cultural History 1840–1918, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, 2002, p 111

[10] Sydney Gazette, 29 April 1820 and 14 October 1820

[11] Sydney Gazette, 29 January 1820

[12] Sydney Gazette, 11 May 1811, p 1

[13] 1 mile burial law, clause 10, An Act for Better Regulating and Preserving Parish and Other Registers of Births, Baptisms, Marriages and Burials in New South Wales and its Dependencies, Including Van Diemen's Land, George IV, no 211, November 1825

[14] In Europe and Britain, the pressures of urbanisation were having a profound effect on the burial of the dead. Overcrowded churchyards, only an acre in size and encroached upon by the living, were offending the sanitary health and religious feelings of the community. The push for burial reform in the early nineteenth century and the consequent cemetery movement was a major cultural shift in death rituals in the westernised world. Colonial Sydney was at the forefront of this movement. Public servants and parliamentary leaders were well aware of the trends overseas and strove (sometimes unsuccessfully) to implement the latest sanitary and philosophical understandings of the appropriate treatment of the dead. Lisa Murray, 'Cemeteries in Nineteenth Century New South Wales: Landscapes of Memory and Identity,' PhD Thesis, University of Sydney, 2001, ch 2

[15] Lisa Murray, 'Cemeteries in Nineteenth Century New South Wales: Landscapes of Memory and Identity,' PhD Thesis, University of Sydney, 2001, ch 2

[16] 'Progress Report from the Select Committee on the Management of Burial Grounds, with Minutes of Evidence', NSW Legislative Council Votes and Proceedings, 1855, vol 3, pp 401–420; 'Progress Report from the Select Committee on the Camperdown and Randwick Cemeteries Bill', Journal of the NSW Legislative Council, 1866, vol 14, part 2, pp 619–702

[17] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 March 1866, p 7

.