The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Bark huts and country estates

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

European settlement along the Cooks River

[media]With the arrival of the Anglo-Europeans, a whole new era opened for the Cooks River valley. The newcomers had a different purpose and with different values had a whole new way of viewing the land and its uses and therefore their relationship with the land.

The supply of food was an immediate concern; the governors were keen to remove reliance on food supplies coming from the home country by establishing agricultural and pastoral activities. The land, its soils and seasons, were unknown quantities and so there were ongoing difficulties for many years. Steps were taken and over time the issue of feeding and housing the colony's population diminished as a matter of major concern.

From their small base on the south-eastern coast of the continent, the newcomers set out to chart their new world. Various expeditions went out to map the area, to make it known and to lay their imprint on it, in the way of roads and buildings.

The gentry gradually began to think of the Cooks River valley as a 'picturesque locality', far from the dirt and polluted water supply of Sydney, yet close enough to town to be only a carriage ride away. The new landowners were motivated by the eighteenth century British tradition of admiration for the picturesque landscape and, wanting the prestige of owning a villa within park-like grounds in the Capability Brown style, they saw the Cooks River as a desirable locality, with its stream, woods and 'fine' sandstone outcrops. The landscape was to be reworked and sculpted to a new aesthetic. But feeding and housing the newcomers was the first priority.

Developing primary production

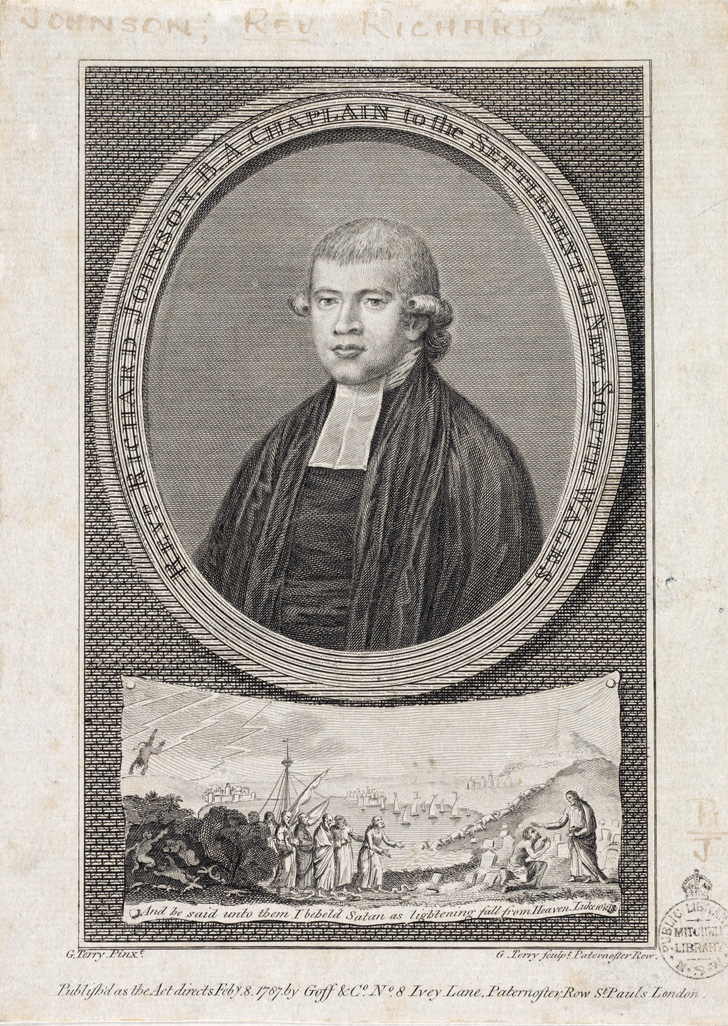

Rev Richard Johnson was [media]an experienced and enthusiastic farmer who immediately began to clear and cultivate his property, Canterbury Vale, with convict labour. Within a year, he could report his first harvest of 'six hundred bushells of Indian Corn', [1] and by 1795 he had 38 acres (approx 15 hectare) in wheat, 30 sheep and 50 goats. In 1799, his farm was extended down to the northern bank of the Cooks River between Canterbury and Croydon Park. William Cox, paymaster of the NSW corps, bought Canterbury Vale in 1800 and extended its area to 600 acres (243 hectares). By 1803, when the Sydney merchant Robert Campbell bought the property, it was carrying 150 sheep, as well as horses and cattle, there was a two acre (.8 hectare) vineyard 'which some years bore abundantly' and an orchard of orange, nectarine, peach and apricot trees. [2]

In the same year, Thomas Moore, the government boatbuilder and purveyor of timber, was granted 760 acres (308 hectare) to the east of Canterbury. This extended his existing 470 acre (190 hectare) Douglas Farm, granted 1799, down to the north bank of the river stretching from Canterbury to Gumbramorra Swamp. [3] He used the land as a source of timber, rather than as a farm, although he rented some of his land close to Sydney to tenant farmers.

Further east, Thomas Smyth, a sergeant in the marine corps, was granted 30 acres (12 hectares) in 1794 and the grant was enlarged to 470 acres (190 hectares) in 1799 on the north side of the river between Gumbramorra Swamp and the swamp near the mouth of Sheas Creek. He worked the land with the help of nine convicts and by 1804, when it was assigned to Robert Campbell in payment of a debt it carried an assortment of livestock including 21 sheep.

In 1808, 800 acres (324 hectares) west of Canterbury Vale was granted to William Faithful. He later exchanged it for better land and the emancipist merchant Simeon Lord took up the property. It was called Brighton Farm and extended along the Cooks River as far as the Punch Bowl ford of the river on the old Aboriginal pathway. The 570 acres (231 hectares) west of the Punch Bowl was granted to Faithful's brother-in-law, James Wilshire, a clerk and storekeeper in the commissary department who had business connections with both Robert Campbell and Simeon Lord. No evidence has been found to suggest that these owners used either of these properties for any purpose other than some grazing and as a source of timber.

South of the river, between 1809 and 1831, land was granted in small parcels of from 30 to 120 acres (12 to 49 hectares), mostly to members of the Sydney Loyal Association, trusted emancipist constables who worked with John Redman, chief constable of Sydney. Redman amassed a landholding of 500 acres (202 hectares) along the south side of the river, covering most of today's Campsie and Belfield, and employed sawyers to clear the timber and supply it as firewood to the Sydney Gaol. Before about 1850, the land in the Cooks River valley was considered to be a 'convenient locality' from which to 'furnish Sydney with split timber, shingles, firewood, charcoal, &c' [4] but it was just too far from Sydney, and transport was too difficult, to allow market gardening to be a viable proposition. From the early days, the timber was considered to be a valuable resource but since few of the new owners actually lived on their properties, regular warnings in the newspapers about trespass were necessary:

NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN, There being great Quantities of TIMBER cut down and destroyed on my and Captain Bunker's farm and adjoining to it, near Sydney, which would have been useful for Naval Purposes, it is therefore particularly requested that no Person will cut down, unbark, or otherwise damage any of the Trees, Posts, Paling, Shingles, &c on the said Premises, unless for the above Use, else they will be prosecuted to the utmost rigour of the Law provided against such Offenders. July 25th, 1803 T.MOORE [5]

Demand for timber

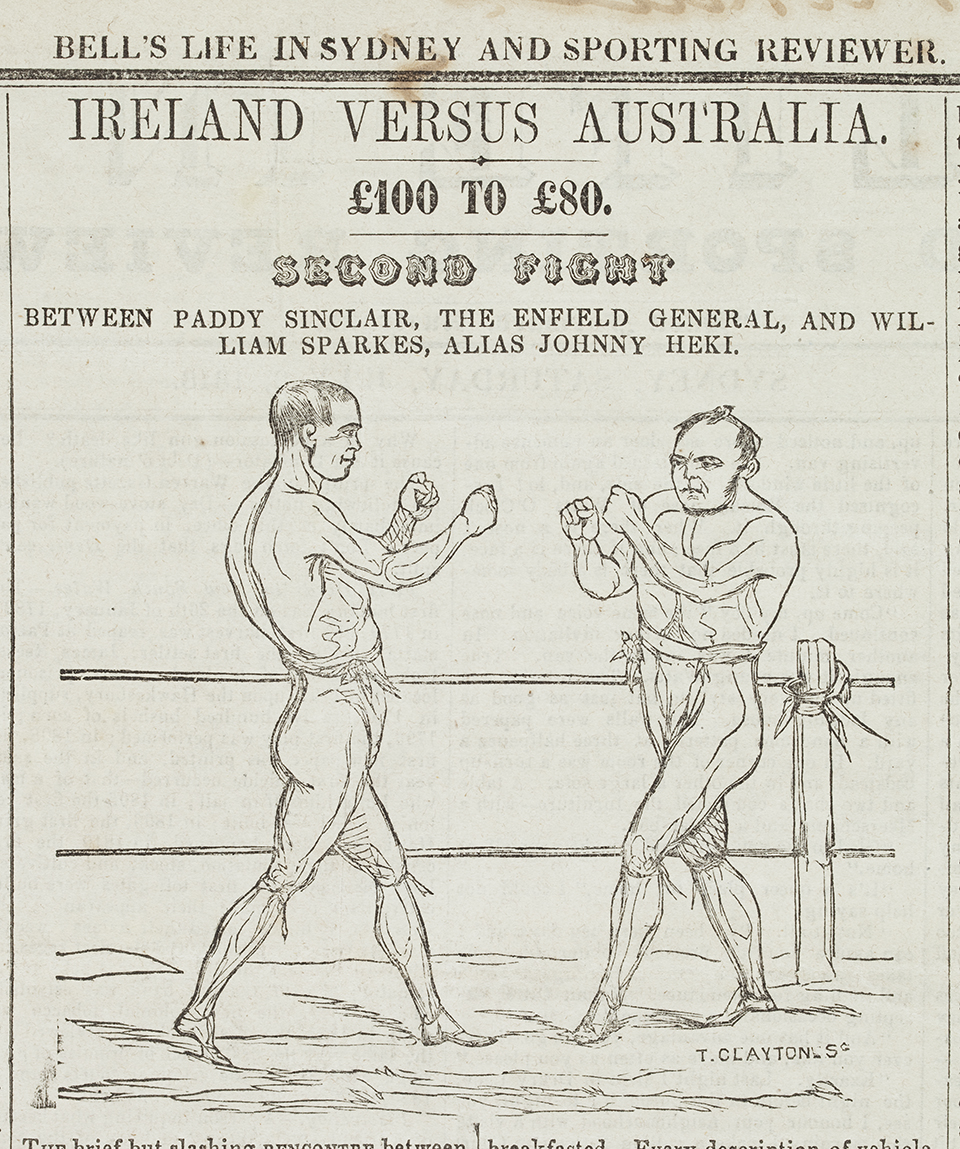

[media]By the mid nineteenth century, a small farming population had settled along the river and creeks and sawyers, shingle splitters and charcoal burners were spread over the rest of the Cooks River valley, wherever the trees were available. Rev James Hassall, curate of St Peter's Cooks River, considered the district 'as wild and godless a place as I have ever known'. [6] It was the home of the 'Cabbage Tree Hat Mob', young sawyers who organised bare-knuckle boxing bouts, cockfights and dogfights in secluded clearings in the forest. The daughter of one of these men remembered:

Mother used to make all our school hats from the leaves of the cabbage-tree palms which grew wild in the Bardwell Creek gully. These cabbage-tree hats, as they were called, were very popular in those days and were worn by nearly everybody. At times my mother used to make extra ones for the gay young 'bloods' of the district. The best hats brought three or four guineas each. [7]

Demand for timber was particularly high during the 1850s and the area became the source of timber sleepers for the new railway from Sydney to Parramatta, which opened in 1855. The more timber on a farm, the higher its value to the owner: 'it is a fortune to a person, I go out there twice a week looking after the timber with a six shooter in my pocket'. After the railway was completed, suburbs began to form along the route and timber was in high demand from owners of brick kilns supplying the building trade.

Market gardening

Once the land was cleared, farmers planted orchards; Frederick Lee, a farmer living on Cup and Saucer Creek, advertised his property for sale, listing an orchard of orange, lemon, citron, apple, pear, peach, loquat, nectarine, apricot, plum, quince, fig, medlar, pomegranate and almond trees [8]:

the orchard … is well worth the attention of any party who can devote his time to the culture of fruits which are now returning a handsome profit to the growers.

[media]Market gardening and dairying became a viable proposition north of the river with the growth of suburban subdivision in the 1850s and 1860s, particularly in the Sydenham farms area and on the Canterbury estate. Once new all-weather roads and permanent river crossings were established, market gardening spread south of the river as well. On the rich alluvial flats near Muddy Creek (Kyeemagh), Nobbs Flat (Earlwood) and along the creeks flowing into the Cooks River, farmers planted potatoes, corn and melons, crops that would not spoil on the rough trip into Sydney. Later, specialist crops like strawberries and flowers were also grown and pig and poultry farmers fattened their livestock on the refuse from Sydney's restaurants. [9] These farmers were to remain on their land until the subdivision boom of the early twentieth century.

Chinese market gardeners rented land along the Cooks River from Croydon Park to Kyeemagh from the 1880s and three of these gardens, at Arncliffe and Muddy Creek, are still operating today. [10]

Establishing water supplies

The Cooks River was either salt or brackish water to the Punch Bowl, the head of the tide. However, it is probable that further west the river and its tributary creeks provided a more or less reliable water supply.

[media]At the end of 1838, when New South Wales was enduring a severe drought, Alexander Brodie Spark, who lived at Tempe on the south bank of the river, had a conversation with the governor Gipps on the subject of damming up the Cooks River for the purpose of obtaining a constant supply of fresh water for Sydney. [11] Busby's Bore, the existing water supply, had not proved to be equal to the demand, so the governor took up the idea with enthusiasm and immediately sent the colonial engineer, George Barney, to survey the river near Tempe. Spark recorded in his diary:

9th November 1838…Major Barney called on me afterwards in town and said that if I did not object to it the dam might be run across below the Bathing house and the only apprehension was that my garden might be flooded. To be surrounded with fresh water instead of salt would be highly desirable and I did not object to his proposal if he could previously ascertain that no bad consequences would follow.

Damming the Cooks River

[media]Completing the sandstone dam took four years. It initially employed a gang of 200 men, mostly convicts, who were housed in a stockade on the north side of the river. In December 1839, a further 170 convicts were sent to commence building on the southern side. The work gave AB Spark an access road from his estate into town, which he inspected with great satisfaction on its completion in August 1840. The dam and sluice gates took a further two years to finish. [12]

Unfortunately, the water of the Cooks River above the dam remained brackish, the porous sandstone dam walls allowing some salt water to permeate through. It failed to provide Sydney with a water supply and the structure itself proved to be a menace to the river's ecology, preventing tidal flushing of deposited urban silt and hastening clogging of the river. In 1869, Thomas Holt, owner of The Warren at Marrickville, offered to build a new dam with his own money in order to secure the water supply, but Edward Campbell, who had a dairy farm opposite, refused to allow it anywhere near his property. [13]

A second dam was built to serve the river's first manufacturing industry, the Australian Sugar Company's refinery at Canterbury. It was a low structure of 'beautiful white sandstone' [14] with stepping stones across the top; the water behind the dam was fresh enough to use in the company's boilers. This dam also served later industries located at the junction of the Cooks River and Cup and Saucer Creek but the industrial pollution that resulted made the water unfit to drink. Deaths from typhoid fever in the droughts of the 1870s and 1880s suggest that the Cooks River was being used as an emergency water supply, but with the arrival of a water supply from the Upper Nepean Scheme after 1888, Sydney's water crisis was solved for the time being.

A barrier to settlement

Although pathways crisscrossed the land linking sites important in Aboriginal physical and social life on both sides of the Cooks River, the stream was seen as an inconvenient barrier by the British, which hindered the settlement of the land south of the river. Watkin Tench's expedition party of December 1790 found the ford of the 'North Arm of Botany Bay' treacherous, describing it as 'only narrow slips of ground, on each side of which are dangerous holes'. [15] One of his party complained that they were 'breast high in water' when crossing and then were forced to wade 'over a swamp of mud which was up to the armpits and like to have smothred several of the men in the mud'. [16] In disgust, Tench reported:

We had passed through the country, which the discoverers of Botany Bay extol as 'some of the finest meadows in the world'. These meadows, instead of grass, are covered with high coarse rushes, growing in a rotten spungy bog, into which we plunged knee-deep at every step.

Surveying the continent

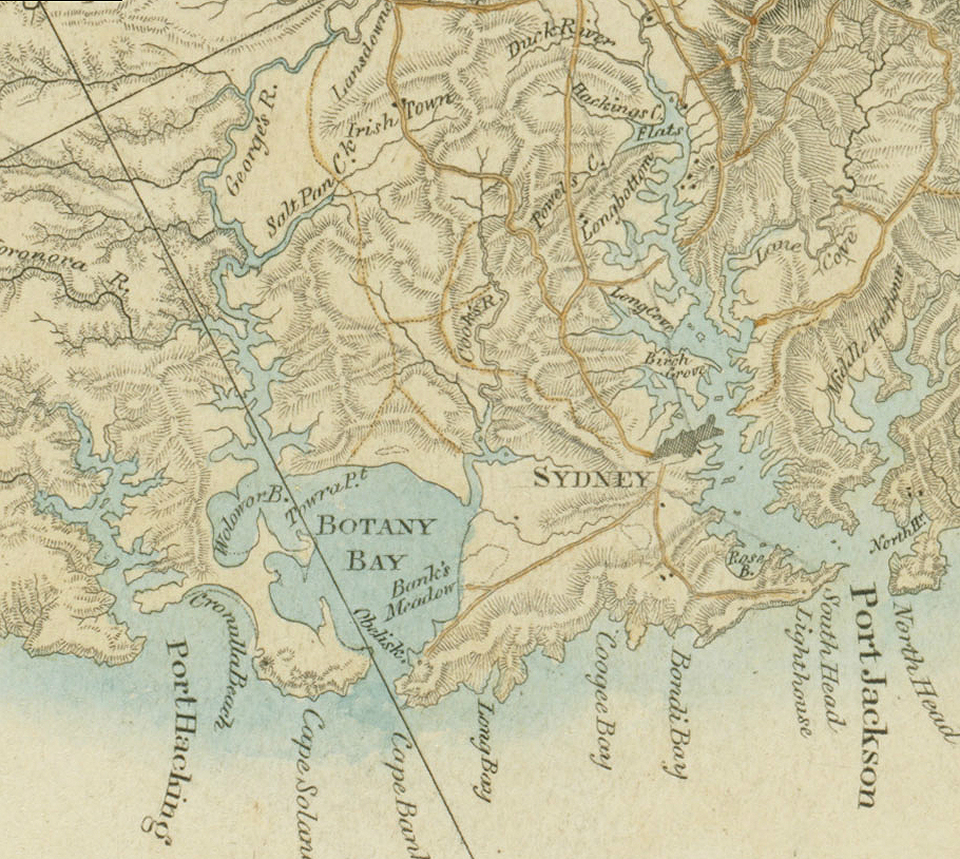

By 1798, surveyor Charles Grimes had followed the existing pathways, successfully surveying and mapping the track to the Georges River from Parramatta River via Long Cove Creek to where the Georges River crosses the Cooks River at the Punch Bowl, the head of the tide. Other tracks branched off this one, leading from the Cooks River to Botany Bay, Kogarah Bay and to Salt Pan Creek. [17] The same year, governor Hunter sent a map to England showing the country around Sydney and on it, for the first time, the Cooks River is named. The name does not appear on an earlier map that Hunter sent in 1796. [18] Later, James Meehan followed the existing tracks to measure out land grants in the district south of the river. [19]

Apart from the 'treacherous' fords somewhere near its junction with Wolli Creek, the earliest recorded reliable ford of the Cooks River was the one at the Punch Bowl, at the junction of today's Georges River Road and Coronation Parade. Aboriginal people had probably been using this crossing long before the British surveyors recorded it.

South of the river

When Hannah Laycock[media] acquired land south of the river at King's Grove in 1804, her family built a 'very slender bad bridge' at a crossing at the end of today's Beamish Street, Campsie. Governor Macquarie, on his tour of the colony in 1810, remarked that it was 'rather dangerous for a carriage'. [20] Early land grants south of the river were measured around the pathways that led to these two crossings, this being the most accessible land for the boundary surveyor. A third crossing, by punt, was opened up around 1814 between Thomas Moore's farm and the heavily timbered land of today's Earlwood. John Parkes, a convict, was assigned to Moore at the government boatyard; he later worked as a sawyer on Moore's Petersham land and was granted his own farm on the other side of the river. It is thought that the punt, near today's Lang Road footbridge, was used to ferry timber across the stream. It was named Pickering's Punt in the 1830s, after a market gardener who rented the fertile river flats nearby.

In 1814, the High Road to Liverpool was built by William Roberts, who received land grants around the headwaters of the Cooks River as a reward. A bridge, known as Moore's Bridge, became the first highway crossing of the river on Liverpool Road and the Cooks River valley became more accessible for cart traffic. In 1821, John Redman advertised a meeting at his house in George Street, Sydney, for all the 'settlers, sawyers and others' residing in the 'Districts of Cooke's River and Botany Bay' to consider 'the necessity of erecting a bridge over the Punch-Bowl Creek'. [21] This became a reliable all-weather road, adding value to the land south of the Cooks River.

North of the river

[media]By the mid-1820s, the land north of the river between Gumbramorra Creek on the east, and the Punch Bowl crossing on the west, was in the hands of only three landowners. Dr Robert Wardell, a barrister who arrived from England in 1824, purchased Thomas Moore's estate. He stocked his Petersham estate with imported deer to provide entertainment for hunting parties that frequently included the governor and the chief military and civil officers. To maintain the security of his livestock, he closed off the track to Pickering's Punt.

West of the river

The Canterbury estate, immediately to the west, had no roads leading to the Cooks River and there was no access to the south along its river frontage. In 1824, Simeon Lord sold Brighton Farm to William Henry Moore, the crown solicitor, who immediately closed off the Old Road to Georges River and warned 'all sawyers, shingle-splitters, wood and grass-cutters' against being found on his farm. Instead, he opened up a road on his western boundary leading from Liverpool Road to the Punch Bowl. This road is today's Coronation Parade, Enfield.

The desire of these three landowners to own undisturbed estates effectively closed access to the Cooks River valley. Woodcutters from areas as near to Sydney as today's Earlwood were forced to take their loaded carts west to the Punch Bowl crossing, up to Liverpool Road and then turn east for town. It added several hours to the journey to Sydney.

Prout's bridge

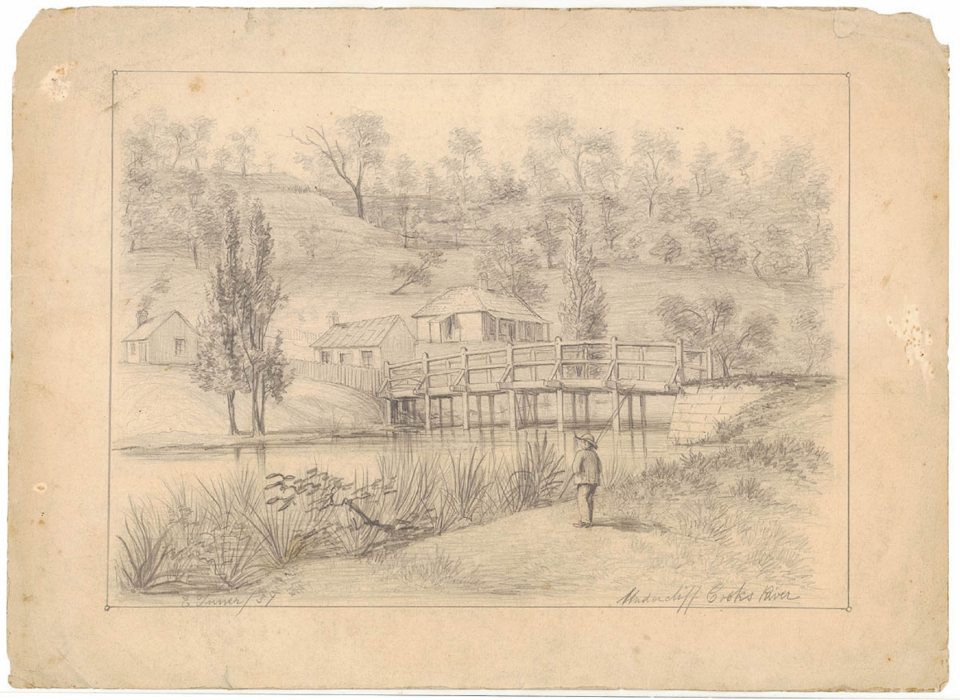

[media]In 1829, Joshua Thorp, the assistant government architect, who owned a country house on the banks of the river at today's Undercliffe, decided to force the issue. With the backing of the governor, Thorp asserted his right of way through Petersham and became the nominal defendant in a case for trespass brought by Robert Wardell. He lost the case, after it was found that no right-of-way was shown on maps in the surveyor-general's office. To add insult to injury, Wardell awarded himself £69 court costs, which the government had to pay. [22] Only one road crossing, ten miles (16 kilometers) from Sydney, remained open to give access to the land between the Cooks and Georges Rivers.

Thomas Mitchell, the surveyor-general, took his revenge in 1831 by surveying a 'Direct Line of Road from Sydney to Illawarra' right through Wardell's Petersham estate. [23] It was not constructed at that time. Instead, Joshua Thorp's brother-in-law, Cornelius Prout, bought a country estate on the other side of the river from the Canterbury estate (now the Canterbury Road crossing) and negotiated an agreement with Robert Campbell to clear a road and operate a punt crossing the river. The Sydney Gazette reported:

We understand that Mr PROUT has just finished a large and substantial punt, at his residence, Cook's River, capable of conveying a loaded wagon and a team of bullocks across the river with perfect ease and safety. This will, no doubt, prove of very great advantage to the settlers in that district, as they may thus save a distance of six miles in their journey to Sydney and avoid a long range of bush-road, at times almost impassable, owing to the want of necessary repairs. Indeed, the settlers in the district of Cook's River have long complained of the want of a proper road to the capital… [24]

There is an ironic postscript to the story. Robert Wardell had indeed ensured the privacy of his estate through his celebrated victory in court but, on 8 September 1834, three convict runaways found Petersham an excellent hiding place to escape capture. Challenged by Wardell near the Cooks River, they murdered him; his body was stiff and cold when discovered by his servants many hours later. [25]

A picturesque retreat

William Cox, Robert Campbell, Thomas Moore and William Henry Moore, the early landowners in the Cooks River valley, used their properties for primary production, timber-getting and grazing, rather than private residences. Farm buildings were constructed to house their labourers, but in each case, the owner's residence was elsewhere.

In the 1820s, however, this situation changed. Better roads encouraged the gentry to think of the Cooks River as a picturesque locality for a country house, far from the dirty and polluted water supply of Sydney yet close enough to town to be only a carriage ride away. The new landowners were motivated by the eighteenth century British tradition of admiration for the picturesque landscape and, wanting the prestige of owning a villa within park-like grounds in the Capability Brown style, they saw the Cooks River as a desirable locality with its stream, woods and 'fine' sandstone outcrops.

Clareville

In 1826, the 60 acre (24 hectare) Alford's Farm near the Punch Bowl, which had been cleared, planted with wheat and grazed 40 cattle, was transferred to Justice John Stephen, who was appointed first puisne judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales in 1825. Stephen also acquired the former grants of John Nichols and Joseph Broadbent nearby and built a country estate, which he named Clareville, on the 250 acres (100 hectares). The residence of Clareville was located on the north side of the road to the George's River, just west of the Punch Bowl crossing of the Cooks River, and is said to have been a single storey spreading colonial bungalow set on the highest river terrace, with a carriage loop in front. [26] The property covered much of today's suburb of Belfield.

Juhan Munna

At about the same time, Robert Wardell acquired the Petersham estate and in 1828 Joshua Thorp brought his new bride to a country house on the other side of the river from Petersham. The difficult negotiations over establishing a right-of-way to his new punt crossing (today's Undercliffe Bridge) have already been described. Thorp called his estate Juhan Munna, said to mean 'to go away' in the Darug language; a name probably supplied by the Aboriginal apprentice he had living in his household. [media]The main house was a very simple colonial style, probably of stone, with a shingled roof and a front veranda. Outbuildings were of slab construction with bark roofs. [27] Thorp planted an orchard of oranges and stone fruit and rented the adjoining 790 acres (320 hectares) of land to the west as a grazing property but as industry moved into the area in 1840 he sought farming opportunities elsewhere. In the early 1840s, he moved his family to the North Island of New Zealand. [28]

Wanstead

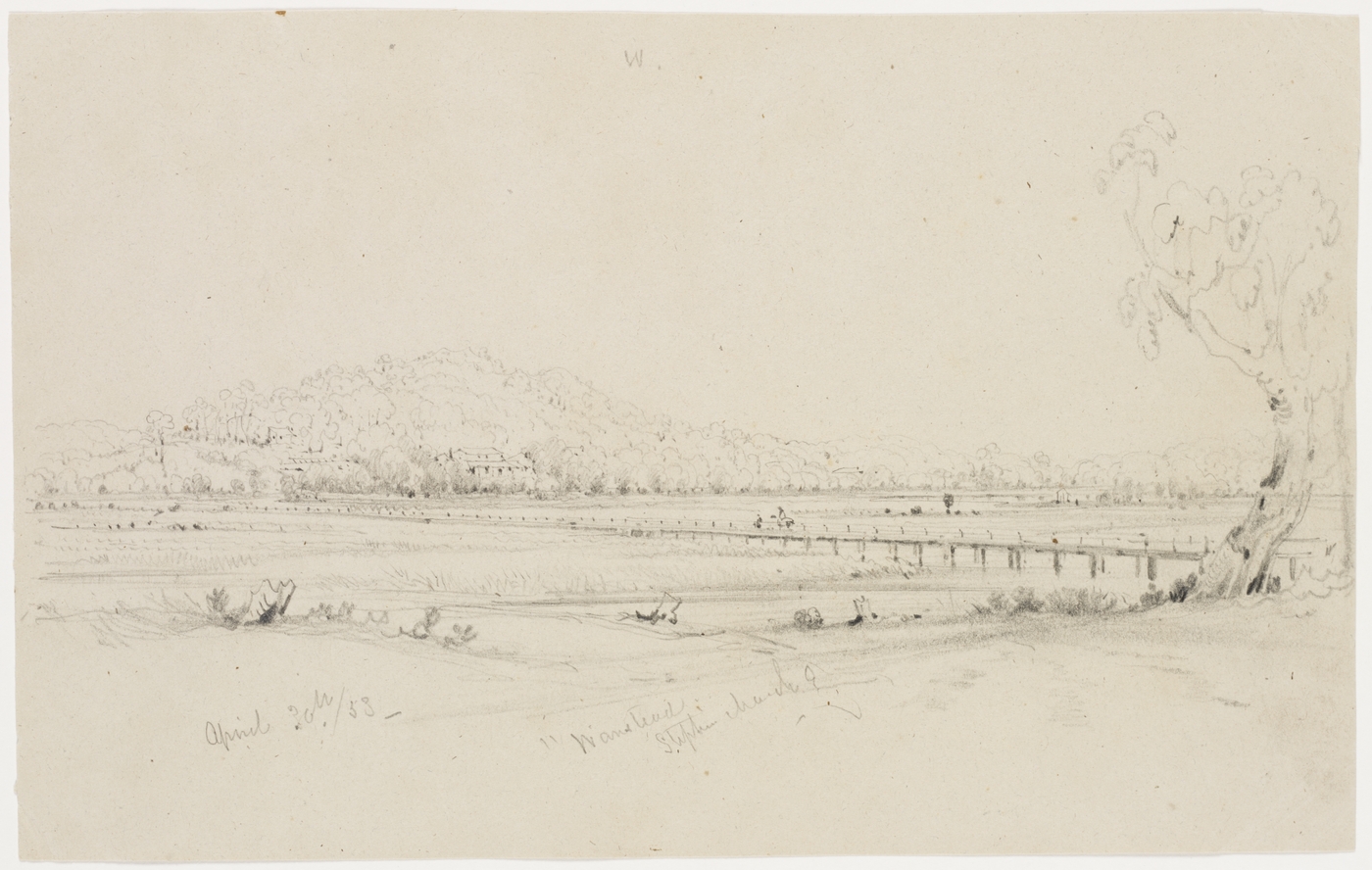

[media]Immediately to the east of Juhan Munna, solicitor, investor and land speculator Frederick Wright Unwin built his country retreat, Wanstead, in 1836. A pencil drawing of the house shows a cluster of single storey buildings on a terrace above the junction of the Cooks River and Wolli Creek. The house was probably of stone construction, with shingle roof; the windows had shutters and the homestead was surrounded by a fenced garden. [29] Unwin also invested in New Zealand and in the Canterbury Sugarworks, but his various speculations sent him bankrupt in the depression of the 1840s and he was forced to subdivide Wanstead to recoup some of his losses. In 1856, a more sympathetic owner, Edward Campbell, turned the river flat property into a dairy farm that lasted until after 1900.

Farming

[media]Other landowners on both sides of the river began to settle on their farms in the 1820s and 1830s. Francis Stephen, who lived with his father at Clareville, bought W H Moore's Brighton Farm adjoining the property on the east and in 1836 subdivided it into mostly five acre (2 hectare) farms, [30] some of which were occupied by the owners; south of the river, as the timber was cut, orchards were planted. Bramshot Farm, at today's Campsie, was described in 1841 as:

A pretty homestead…weather-boarded, brick-nogged Verandah Cottage around which is a first-rate garden, well stocked with choice fruit trees, under a high state of cultivation. The Cottage forms part of a sweet villa residence, with coach house and stabling detached; also, overseer and men's huts, weatherboarded and shingled and all within a fence surrounding the Cottage; besides a water hole, an immense lagoon furnishes this property with a never-failing supply of pure water… [31]

The 'immense lagoon' is now Croydon Park and Picken Oval.

Tempe estate

[media]None of the estates described so far had pretensions to grandeur. The houses were pleasant, but of local vernacular construction. In 1828, however, Alexander Brodie Spark, a merchant, bought land grants on the south side of the Cooks River between Wolli Creek and Muddy Creek and, being an art connoisseur, designed himself an estate in the best traditions of gentleman farmers back in Britain. He commissioned John Verge, the most fashionable architect of his day, to design him a suitable house for his Tempe estate, named after the valley in classical Greece. Tempe and its landscaped grounds became famous, both within the colony and outside it. Lady Franklin, the wife of the governor of Tasmania, visited in 1840:

To the left and behind Tempe, rock rises steep, but is of most insignificant height, though styled Mt Olympus – forms a sort of small promontory, at the foot of which is a small wharf or jetty and bathing house…view from Mt Olympus of winding of river in flat bush and swamps and see heads of Botany Bay – all ugly enough…garden walks at right angles crossing and Norfolk Island pines at intersections…orange and lemon trees…casuarina trees stripped of leaves with convenient branches planted in aviaries for perches of birds.

Canterbury House

Further along the river, about 1850, Arthur Jeffreys RN and his wife Sarah Campbell commissioned Edmund Blacket to build them a rustic gothic residence. Canterbury House, on a hill overlooking the Cooks River, had all the refinements – an orangery, a circular drive and spectacular flower garden filled with camellias and azaleas, a 'lodge' at the gate, as well as a clearing creating an impressive vista of the house from the Cooks River. A carriage road lined with pine trees led to Ashfield railway station. In the 1870s, the house was sold to John Hay Goodlet, who owned a very large business selling building materials. It was demolished in 1929.

The Warren

In 1857, Thomas Holt, merchant and investor, bought part of Petersham from the estate of Dr Robert Wardell and built a [media]house, The Warren, designed by George Allen Mansfield. A stalwart of the NSW Acclimatisation Society, Holt stocked the property with imported rabbits to provide harmless hunting amusement for his friends. To promote the objects of the society, Holt invited the governor, Sir John Young, and a number of public men to his property to a luncheon at which all the viands consumed – animals, fruits and vegetables – had been introduced into the colony and acclimatised, including 'delicately flavoured rabbits' and 'unusually fat lambs'. [32] Reporters of the Sydney Morning Herald described the estate in 1868:

The mansion itself, of noble extent and standing on the summit of a hill, is the most prominent feature in the view…The scenery of 'the Warren' is bold and fine. Nature has done much, but she has been materially 'assisted' by art. The sight of a rabbit or two scampering off now and then towards their burrows gives life to the scene…Mr Holt has erected a very picturesque little building for a 'Turkish Bath', near the river and opposite to this building stands a small bathing house, belonging to Mr Campbell. [33]

The Warren was built from stone quarried on the property and had 30 rooms, including a dining room which could seat 50 to 60 and a picture gallery 30 metres long and five metres wide. Schoolchildren were encouraged to come to the house to view the sculptures and paintings and to picnic in the grounds. Holt had burial vaults cut from the sandstone beside the river.

When Holt planned to return to England, he tried to sell the house to governor Augustus Loftus as his country residence, but the government acquired Hillview in the Southern Highlands for Loftus and his family instead. Eventually the house became a Carmelite convent, then during World War I it was used as an artillery camp. It was demolished in 1919 and Sir John Sulman was engaged to build a housing estate for returned soldiers on the site.

Painting the Cooks River valley

[media]Building a mansion in the best picturesque tradition was only for the wealthy, but the public could be encouraged to appreciate the fine landscape of the Cooks River valley through the work of artists. One of the earliest painters to work in the area was the emancipist forger Joseph Lycett, who produced two views of the Cooks River where it flowed into Botany Bay. [34] Lycett, a portrait painter, brought with him an image of how trees should be painted and it is evident in the paintings that he found it difficult to adapt to the very different Australian vegetation. His representation of the Cooks River could equally be English woodland.

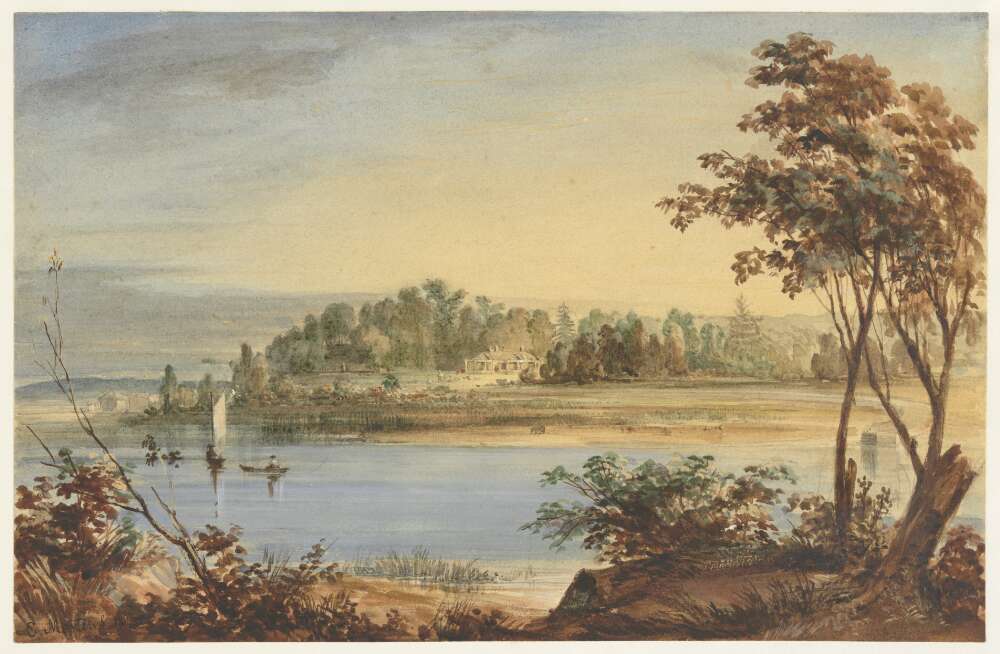

Conrad Martens[media] arrived in Sydney in 1836 and very soon established himself as society's favourite painter. A B Spark thought his paintings 'superior to any thing I have seen in this Colony' and, in the spring of 1837, arranged to have his Tempe immortalised on canvas. Marten's work was eminently satisfactory – Spark wrote 'It forms as beautiful a landscape as I think I have ever seen'. [35] The paintings of Martens were in the style of J M W Turner's early English landscapes of 20 years earlier, when many of the colonial gentry would have acquired their taste in art and culture. Martens also immortalised Canterbury House in the same style in 1860 for the Jeffreys family, just before they went to England.

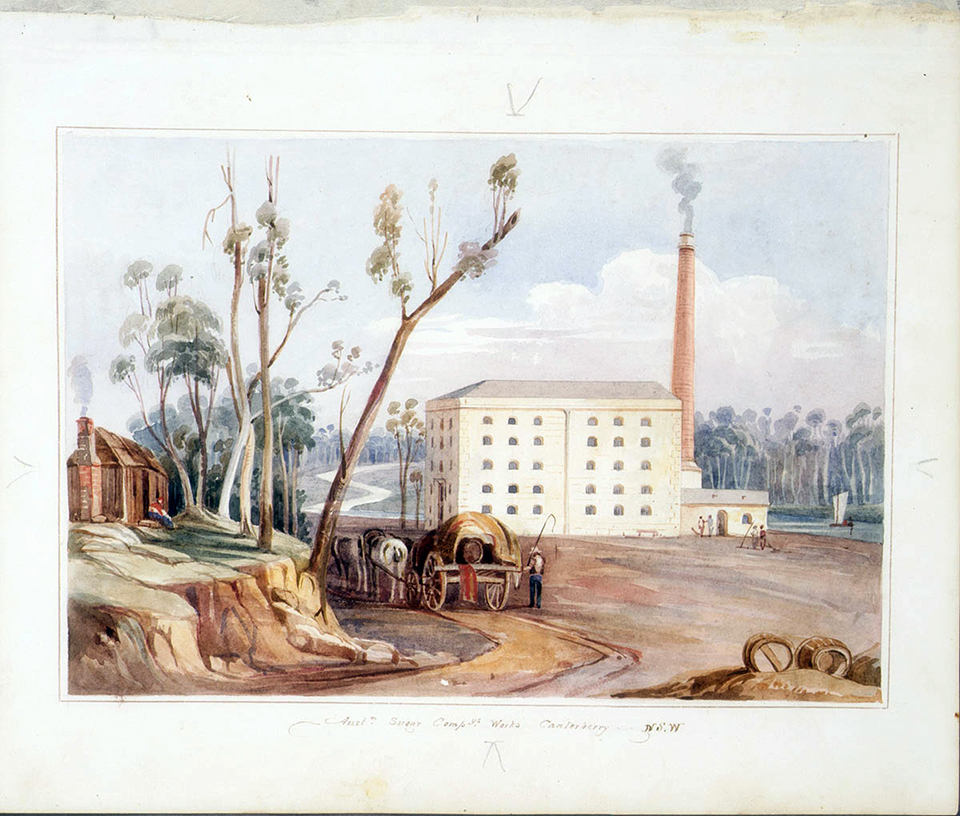

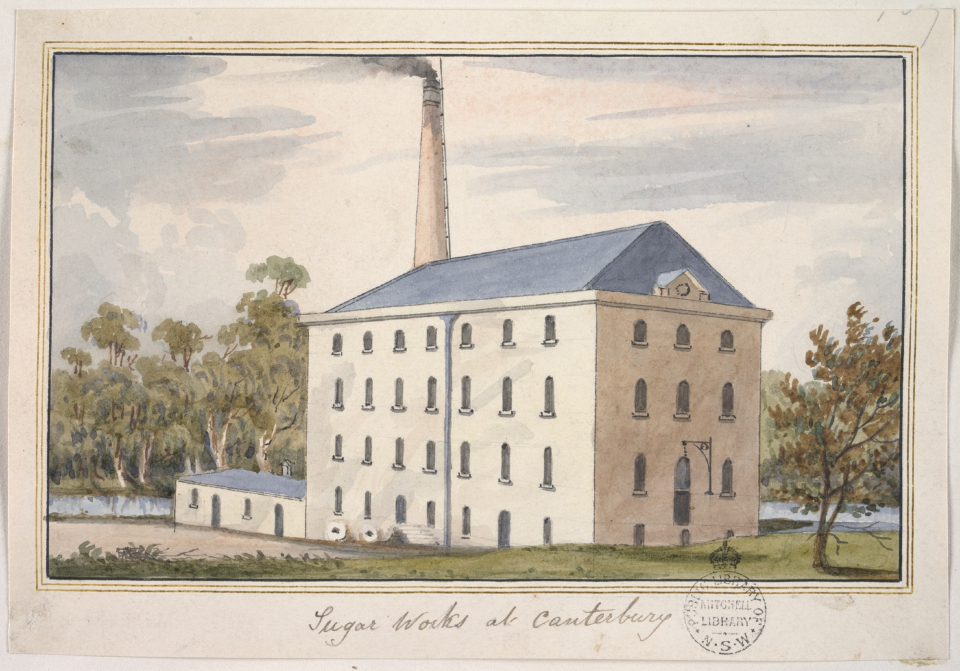

Frederick Garling [36] painted [media]the Canterbury Sugarworks soon after the factory opened in 1842. A painting formerly [media]attributed to Joseph Fowles is clear and detailed. [37] Garling's painting is a much more interesting representation in that it places the factory in the context of its surroundings, showing a cleared space beside the building, which had obviously been the builder's yard, a slab hut and a delivery cart on the road.

Samuel Elyard,[media] a very prolific painter of Sydney's scenery, grew up in Sydney. He produced several paintings of the river from Prout's Bridge to Tempe, between the early 1840s and the 1860s. Influenced by his teachers Conrad Martens and John Skinner Prout, his watercolours are beautifully composed and show a romantic landscape but with, as far as we can estimate, perfect accuracy. He always painted his studies from life.

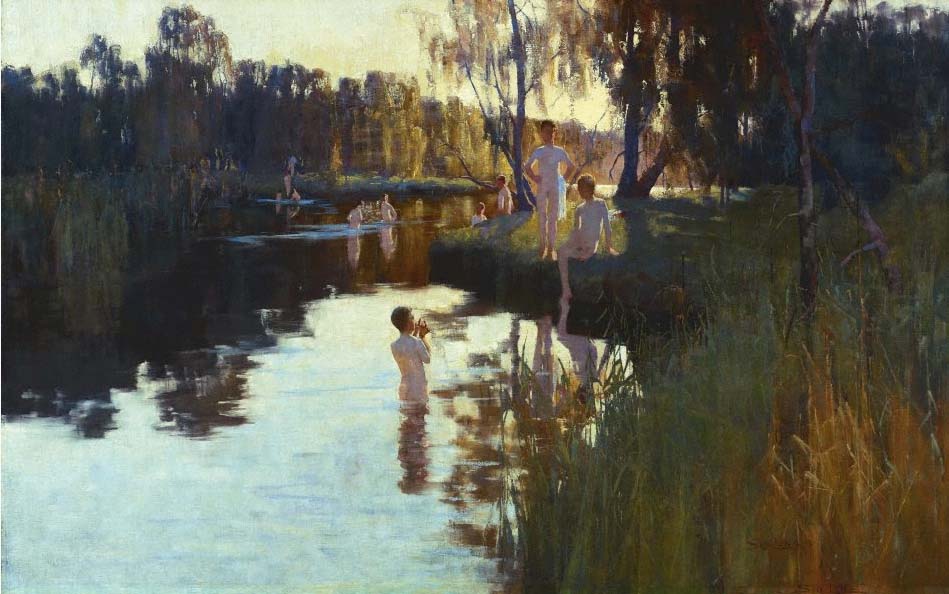

[media]Probably the best-known nineteenth century painter to work in the area was Sydney Long, whose first major oil painting, By Tranquil Waters, showing the junction of the Cooks River and Wolli Creek, was purchased by the National Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1894. He returned to the area again to paint Edward Campbell's dairy farm, a painting now held in the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery.

References

Alexander Brodie Spark diaries, 1 January 1836–22 September 1856, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, A4869

Noxious and Offensive Trades Inquiry Commission and New South Wales, Noxious and Offensive Trades Inquiry Commission Report, Sydney, 31 May 1883

Watkin Tench and LF Fitzhardinge, Sydney's First Four Years: Being a Reprint of, 'A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay,' and, 'A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson', Angus and Robertson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1961

Notes

[1] Richard Johnson and George Mackaness (ed), 'Letter to Thomas Gill, 29 July 1794', reprinted in Some Letters of Rev Richard Johnson B. A., First Chaplain of New South Wales, Review Publications, Dubbo, 1978

[2] Joseph Holt and Thomas Crofton Crocker, Memoirs of Joseph Holt, General of the Irish rebels, in 1798, Edited from his Original Manuscript, vol 2, London, Colburn, 1838

[3] Frederick Watson and Peter Chapman, Historical Records of Australia, Series III, Despatches and Papers Relating to the Settlement of the States, vol 3, Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, Sydney, 1921

[4] James Chandler, advertisement, The Sydney Gazette, 18 June 1833

[5] The Sydney Gazette, 17 July 1803; Thomas Moore's farm extended across much of today's Marrickville and Petersham

[6] James Samuel Hassall, In Old Australia: Records and Reminiscences from 1794, Library of Australian History, North Sydney, 1977

[7] Interview with Mrs Frances Cary, daughter of Isaac Parkes, The Propeller, Hurstville and district local paper, 30 November 1939

[8] The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 March 1854

[9] Noxious and Offensive Trades Inquiry Commission, Report of the Royal Commission, appointed on the 20th November, 1882, to Inquire into the Nature and Operations of, and to Classify Noxious and Offensive Trades, Within the City of Sydney and its Suburbs, and to Report Generally on Such Trades, together with the minutes of evidence and appendices, New South Wales Legislative Assembly, Sydney, 1883

[10] 'Arncliffe Market Garden', 'Kyeemagh Market Garden' and 'Toomevara Lane Market Garden', State Heritage Inventory, NSW Government Environment and Heritage website, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/Heritage/searchesdirectories.htm

[11] AB Spark, 5 November 1838, Alexander Brodie Spark diaries, 1 January 1836–22 September 1856, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, A4869

[12] Letters to the governor from the colonial engineer; 1831–1846, NSW Civil Establishment, Returns of the Governor, Colonial Secretary's Correspondence: Special Bundles, 1846–56, State Records Authority of New South Wales, 4/7344

[13] The Sydney Morning Herald, 18 January 1869

[14] The Sydney Herald, 4 October 1841

[15] Watkin Tench and LF Fitzhardinge, Sydney's First Four Years: Being a Reprint of, 'A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay,' and, 'A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson', Angus and Robertson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1961, p 205

[16] John Easty, Memorandum of the Transactions of a Voyage from England to Botany Bay, 1787–1793: A First Fleet Journal, Angus and Robertson in association with the Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1965, p 122

[17] All early maps show the same pattern of tracks, for example, Plan of Part of Cumberland Shewing the New Lines of Road, 1830, AO 5035, and Plan of a Direct Line of Road from Sydney To Illawarra, 1831, AO 5037, both use a base map with the early tracks noted by Grimes and Meehan marked on it, State Archives of New South Wales

[18] James Jervis, A History of the Municipality of Canterbury, Canterbury Municipal Council, 1951

[19] James Meehan, Surveyor's Field Book 23, 1807, State Records Authority of New South Wales, SZ860; Surveyor's Field Book 61, 1808, State Records Authority of New South Wales, SZ884

[20] Lachlan Macquarie, Lachlan Macquarie: Governor of New South Wales: Journals of His Tours in New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land, 1810–1822, Library of Australian History in association with the Library Council of New South Wales, Sydney, 1979, p 37

[21] The Sydney Gazette, 26 May 1821

[22] Lesley Muir, 'A Wild and Godless Place: Canterbury 1788–1895', MA Thesis, University of Sydney, 1985

[23] William Lygon, 'Leichhardt and Petersham Friendly Societies Dispensary Limited, Illuminated Address', Collection of Illuminated Addresses, Albums of Views and Other Works Presented to His Excellency, Earl Beauchamp, Governor of New South Wales, 1899–1901, vol 36, State Records Authority of New South Wales, A5037

[24] The Sydney Gazette, 18 June 1833

[25] The Sydney Monitor, 10 September 1834

[26] Lesley Muir, personal communication with May Lees, 1985

[27] Edward Turner Undercliff, Pencil Drawings of Sydney and Surrounds, ca 1857, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, PXE 879/1

[28] Joshua Thorp, correspondence with William Woolcott, private collection

[29] Conrad Martens, 'Wanstead; Stephen Marsh Esq., April 30, 1853' in Sketches in Australia, 1835–1865, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, PX295

[30] PL Bemi, Plan of Allotments, Brighton Farm and Part of Burwood Estate, map, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, M2 811.1835/1838/1

[31] The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 April 1841

[32] Henry E Holt, An Energetic Colonist, Melbourne, Hawthorn Press, 1972, p 23

[33] The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 August 1868

[34] Joseph Lycett, 'View of the Heads, and Part of Botany Bay – from the End of Cook's River' in Views of Van Diemen's Land and New South Wales, 1822–1823, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DGD 1,5; Joseph Lycett, 'Botany Bay', ca 1822 in Views in Australia, or, New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land Delineated: In Fifty Views with Descriptive Letter Press, London, J Souter, 1824–25

[35] AB Spark, 5 November 1838, Alexander Brodie Spark diaries, 1 January 1836–22 September 1856, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, A4869

[36] Frederick Garling, Australian Sugar Company's Works, Canterbury, ca 1842, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales, DG SV1A/13

[37] Previously attributed to Joseph Fowles after comparison with his 'Sydney in 1848', however, at least one watercolour 'Government House' (now separated from the album) is now thought to have been by Frederick Garling (ML 70). Others bear a close resemblance to drawings by 'J.B 1840' in the Richard Jones scrap album (PXA 972). It seems unlikely that Fowles is the artist of these drawings — Curator, Mitchell Library, 2003

.